Abstract

Previous correlational studies showed the importance of mindfulness and autonomous goal motivation for goal pursuit, goal setting, and goal disengagement processes. The present study examined the role of mindfulness in goal regulation processes for self-selected personal goals in a randomized waitlist control group design. Participants (N = 228, M = 30.7 years, 18–78 years; 84% female) either received daily 9-12-minute audio mindfulness exercises online for four weeks or were placed on a waitlist. Participants in the intervention group (N = 113) reported more goal progress compared with the control group (N = 116) at the end of the intervention. Autonomous goal motivation for already set goals did not influence change in goal progress. However, autonomous goal motivation for newly set goals was higher in the intervention group than in the control group. Additionally, we tested the role of mindfulness in interaction with goal attainability and autonomous motivation for goal adjustment processes (in this case, reduction of goal importance). In the control group, lower goal attainability at baseline was associated with a greater reduction in goal importance for less autonomous goals. For more autonomous goals, change in goal importance was independent from baseline attainability. In contrast, in the intervention group, all goals were slightly devalued over time independently from autonomous motivation and goal attainability at T1. Moreover, changes in goal attainability were positively linked to changes in goal importance over time. This effect was moderated by mindfulness and autonomous motivation. Overall, the findings point to the relevance of mindfulness and autonomous motivation for goal regulation processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

People pursue personal goals such as learning Italian, going on a vacation, doing Yoga, or becoming more assertive. Personal goals are important in defining an individual’s identity and providing structure and guidance in everyday life (Brunstein et al., 1999; Emmons, 1996). Previous research has demonstrated the positive effects of persisting in the face of goal pursuit difficulties for success in several life-domains (Credé et al., 2017; Duckworth et al., 2019) and for well-being (Disabato et al., 2019). Evidence also shows that goal progress is positively associated with well-being in general (Klug & Maier, 2015). However, even after people make progress on their goals, some can become out of reach or consume too many resources resulting in futile or even maladaptive goal pursuit (Kalia et al., 2019; Lucas et al., 2015). In these situations, processes of goal adjustment (i.e., devaluing the goal, positively reinterpreting negative event, redirecting resources to other attainable goals, goal disengagementFootnote 1) may represent a more adaptive way to preserve resources and focus on more achievable goals (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002; Brandstätter & Bernecker, 2022; Heckhausen et al., 2010; Kappes & Schattke, 2022; Wrosch et al., 2003) resulting in maintenance or restoration of well-being (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994; Ghassemi et al., 2017; Heckhausen et al., 2019; Kappes & Greve, 2023; Wrosch et al., 2003; meta-analysis: Barlow et al., 2020). The successful interplay between persistent goal pursuit (goal engagement) and flexible goal adjustment has been theorized to be important for adaptive self-regulation of goal pursuits (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002; Baltes, 1997; Haase et al., 2013; Heckhausen et al., 2019). It presumes that a person takes the attainability of a goal into account (including an evaluation of available resources) and adjusts goal pursuit and goal importance accordingly (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002).

Factors that support successful goal pursuit have been extensively studied (for an overview, see Brandstätter and Bernecker, 2022). Recent research has identified mindfulness and autonomous goal motivation (i.e., selecting and pursuing goals because they reflect personal values and interests, Sheldon and Elliot, 1999) as relevant factors for goal regulation (e.g., Marion-Jetten et al., 2022), particularly goal progress and goal setting (e.g., Smyth et al., 2020). However, the correlational designs of these previous studies preclude conclusions on causal relationships between these variables. Moreover, less research has focused on factors that promote processes of goal adjustment, despite its important role in adaptive goal pursuit (for a recent overview, see Kappes and Schattke, 2022). The influence of mindfulness and autonomous motivation on these processes has rarely been considered in previous research. We argue that the investigation of the role of the same factor on goal setting, goal pursuit as well as goal adjustment within one study might allow a better understanding of its functioning. The purpose of the present study was thus twofold. First, by implementing an experimental design (4-week intervention study with waitlist control group), we aimed to substantiate the effect of mindfulness and autonomous goal motivation on goal progress for already set goals and the role of mindfulness on autonomous motivation for setting new goals. Second, we exploratorily investigated changes in goal importance (one of the processes of goal adjustment) as a function of mindfulness, goal attainability and autonomous motivation for already set goals.

Mindfulness and goal progress

Mindfulness is “generally considered to be a receptive state of observing without judgment [of] what is occurring, without specific goals or aims” (Ryan et al., 2021, p. 300). It can be measured as a disposition (how mindful one tends to be) or as a state. Both foster momentary awareness of inner (e.g., thoughts, feelings, desires, but also physiological processes) and outer (e.g., sounds, odors, other people) stimuli (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Kabat-Zinn, 2003). As such, it supports the processing of more information and makes it more likely that people will consider a fuller range of information when making choices (Brown et al., 2007; Langer, 1989). Mindfulness has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms (Goleman & Davidson, 2017; Goyal et al., 2014; Lahtinen et al., 2021). It can also help people to cope better with unpleasant emotions (e.g., Brown et al., 2013; de Vibe et al., 2018; Heppner et al., 2015; Marion-Jetten et al., 2022).

Since these processes all represent aspects of goal pursuit, it is not surprising that an increasing amount of goal research has recently focused on the role of mindfulness. For example, Spence and Cavanagh (2019) demonstrated that interventions using different aspects of, or promoted by mindfulness (contemplative perspective [meditation] vs. cognitive-attentional perspective [attention training] vs. socio-cognitive perspective [mindful creativity]) were all effective in increasing goal progress for personal goals. Moreover, Marion-Jetten et al. (2022) reported negative longitudinal associations between dispositional mindfulness and action crises – the motivational conflict between continuing pursuing the goal versus letting it go, usually following accumulation of setbacks (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013). One could thus infer that mindfulness promoted more efficient goal pursuit in their studies, by reducing this conflict. Finally, Smyth et al. (2020) reported that dispositional mindfulness was positively related to goal progress in university students over one year. Overall, these findings lend support for the effectiveness of mindfulness in supporting goal processes associated with increased goal progress.

Mindfulness and autonomous goal motivation

Most of the aforementioned studies have identified autonomous goal motivation as a mediator in the relation of mindfulness to goal processes. This construct stems from self-determination theory (SDT - Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2017), particularly the self-concordance model, which proposes that the reasons for which people pursue goals influence their goal progress and psychological well-being (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). Self-concordance refers to the degree of concordance between an individual’s goals and their personal values and interests (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). Accordingly, goal pursuit can be distinguished as stemming from autonomous versus controlled motivation. A personal goal is autonomous when a person pursues it because she finds it fun or interesting (intrinsic motivation), because it integrates harmoniously within her value system (integrated motivation), or because she finds it important (identified motivation). In contrast, a goal is controlled when a person pursues it to avoid feelings of shame and guilt or to impress others (introjected motivation), or to obtain rewards and prevent punishments (external motivation).

Importantly, autonomous goal motivation has consistently been associated with positive outcomes in terms of goal pursuit (e.g., more goal progress; Hortop et al., 2013; Howard et al., 2021; Koestner et al., 2008; Riddell et al., 2023; Sheldon and Elliot, 1999) and well-being (e.g., vitality; Nix et al., 1999; Ryan and Frederick, 1997). On the other hand, controlled goal motivation has shown mixed findings. It has been found to be negatively associated with goal progress and positively associated with goal-related difficulties (i.e., action crises, Holding et al., 2017) or unrelated to goal progress (Koestner et al., 2008). It has also been positively related to negative indicators of well-being (e.g., depressive symptoms, lower satisfaction with life, Brunet et al., 2015). While most of the studies within an SDT framework have focused on the social/interpersonal context (autonomy-supportive vs. controlling) as the main influence on a person’s motivation, attention has recently shifted to the intrapersonal factors that can support autonomous motivation, such as mindfulness. In an earlier study, Brown and Ryan (2003) found that both dispositional and state mindfulness could positively predict variations in daily experienced autonomy. Based on these findings, Sheldon (2014) proposed dispositional mindfulness as a potential precursor for autonomous goal motivation, which has been empirically supported in several studies (Marion-Jetten, Taylor, & Schattke, 2022; Smyth et al., 2020). Marion-Jetten et al. (2022) also showed that autonomous goal motivation and emotion regulation mediated the relation between mindfulness and action crises. Finally, Donald and colleagues’ (2020) meta-analysis supported the link between mindfulness and autonomous motivation. These findings support the view that mindfulness is beneficial for goal pursuit. Indeed, people with higher levels of mindfulness should select and pursue more autonomously motivated goals, which, in turn, should then lead to more goal progress and psychological well-being benefits.

Mindfulness and goal adjustment

Additionally, the attentive and accepting stance afforded by mindfulness might also facilitate earlier detection and acceptance of unsurmountable obstacles and their associated negative feelings and, thus, facilitate processes of flexible goal adjustment (e.g., devaluation of goal importance, redirecting attention to achievable goals; Brandtstädter and Rothermund, 2002, p. 124). Supporting that idea, Schmitzer-Torbert (2020) provided correlational evidence that mindful people were less likely to continue investing resources in an unprofitable course of action. Hafenbrack et al. (2014) further showed that mindful individuals’ decisions were less biased by sunk costs (i.e., the tendency to want to continue something once one has invested a lot of resources), because of their focus on the present (instead of past investments) and reduced negative affect. Mindfulness has also been shown to be related to a broader attentional scope (Slagter et al., 2007), increasing divergent thinking and cognitive flexibility (Colzato et al., 2012). Brandtstädter and Rothermund (2002) suggested that goal adjustment processes are related to a particular cognitive set characterized by defocalized attention and holistic processing, increased availability of cognitions enhancing goal disengagement, and greater sensitivity to external stimuli. Mindfulness could increase these processes through its influence on broader attentional scope, cognitive flexibility, etc. (see also Hommel, 2015, for a discussion of mindfulness and cognitive flexibility).

Goal adjustment and autonomous goal motivation

The role of mindfulness in the goal adjustment process might be moderated by the extent of autonomous or controlled goal motivation people have for their goals, respectively. Smyth et al. (2020) point out, “pursuing non-concordant goals can lead people to waste time and energy on goals that, even if attained, will not benefit their well-being or development (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; cf. Milyavskaya & Werner, 2018).” (p. 1). Thus, in the context of already set goals, mindfulness might facilitate adjustment of non-concordant goals (i.e., less autonomous and more controlled goals). Indeed, according to Ryan et al. (2021), mindfulness “facilitates greater alignment of actions with internalized values, the pursuit of extrinsic goals, such as status or wealth, is less likely among more mindful individuals because such goals are not readily or wholly self-endorsed” (p. 303). Thus, increasing mindfulness could support people in focusing on their autonomously motivated goals while devaluing the importance of less autonomous/more controlled goals. Devaluing less autonomous goals might even be independent from goal attainability due to the realization that achieving those goals would not satisfy or reflect one’s values or interests (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

At the same time, mindfulness might also help people disengage from unattainable and difficult autonomously motivated goals. Although being autonomously motivated for one’s goal seems to shield a person from experiencing an action crisis (Marion-Jetten, Taylor, & Schattke, 2022), it might be disadvantageous when the goal is too resource-consuming or unattainable. Letting go of an autonomously motivated goal which is not attainable may pose a larger threat to identity or experience of loss and, thus, impede processes of goal adjustment. In a laboratory study, Ntoumanis et al. (2014) demonstrated that participants with higher autonomous goal motivation felt less ease in cognitively disengaging from an unattainable goal. These findings are first indicators that autonomous goal motivation can complicate goal adjustment. However, this study only looked at adaptation processes on a short time scale. Moreover, they did it in isolation from a potential influence of mindfulness, thereby missing a boundary condition of autonomous motivation’s effect on goals whose pursuit has become futile (i.e., when goal attainability is low or too resource-consumptive).

Present study

In response to the paucity of experimental research testing the effect of mindfulness on goal selection and motivation, goal pursuit, and goal adjustment, we conducted a 4-week mindfulness online-intervention study with a waitlist control group design. Participants in the mindfulness condition were given short daily online mindfulness exercises that lasted 9–12 min. This choice was motivated by existing evidence of a positive effect of short daily exercises in online mindfulness interventions on wellness-related (lower stress, higher well-being, lower depression symptoms) and health-related outcomes (improved sleep quality; Lahtinen et al., 2021; Moszeik et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020). These findings mirror effects of offline mindfulness interventions (e.g., Donald et al., 2016; Schultz and Ryan, 2019). Together, these findings indicate that an online intervention would be suitable to causally test the effect of mindfulness on goal regulation.

To test the effectiveness of the intervention in the present study in general, we examined self-reported mindfulness, well-being, and stress. We hypothesized that mindfulness (H1a) and well-being (H1b) would increase in the intervention compared to the control group, while stress would decrease in the intervention compared to the control group (H1c).

We studied the effect of the mindfulness intervention on already set goals as well as on newly set goals. In particular, we hypothesized that goal progress for already set goals would increase for participants in the mindfulness intervention compared to the control group (H2). Moreover, autonomous goal motivation would be associated with an increase in goal progress (H3), and this would be particularly the case in the intervention compared to the control group (H4). Finally, we examined the effect of mindfulness on autonomous goal motivation for new goals, hypothesizing that participants in the intervention group compared to the control group would report higher autonomous goal motivation for newly set goals (H5).

Additionally, given that we did not have a specific confirmatory hypothesis, we explored the interactive effect of the mindfulness intervention with autonomous goal motivation and goal attainability on changes in goal importance, one of the processes of goal adjustment.

Methods

All research reported in this paper was approved by the authors’ University Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data, materials, and supplementary material can be obtained on OSF: https://osf.io/pa79b/.

Participants

The study was advertised via the authors’ institute’s homepage, social media channels, the online study advertisement page of the magazine Psychologie heute (i.e., “Psychology today”), a regional newspaper, and private contacts using a snowballing principle. The eligibility criteria were: being 18 years or older and not having a current acute mental or physical illnesses requiring treatment (e.g., epilepsy, alcohol or drug abuse, panic disorder, borderline, suicidal thoughts, manifest depression, psychosis, PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder). If potential participants had a psychiatric diagnosis, they were asked to discuss the possibility of participation with their therapist. Potential participants were briefly informed about mindfulness, its effects, and the procedure of the study on the study’s webpage. Interested people could register to participate on this webpage.

In total, 261 people registered to participate in the study and received a link to the first questionnaire that included the random assignment to the intervention versus waitlist control group at the end of the questionnaire. Of these, 229 completed the questionnaire and were assigned to one of the groups. One of these participants was excluded from analyses because this participant showed very suspicious data (patterns of only choosing highest or lowest values in each scale). Random assignment resulted in 112 participants in the intervention group and 116 participants in the waitlist control group. There were no significant differences between the groups concerning demographic variables (see Table 1).

About three quarters of the sample (n = 171 participants) participated at T5. This subsample compared with the participants that did not participate at T5 did not differ at T1 in terms of age, gender, educational level, or student status, ps > 0.206.Footnote 2 More participants from the control group (80%) than from the intervention group (69%) were retained in the sample at T5. They may have been more motivated to remain in the study because participants in the waitlist control group could only receive material for the mindfulness exercises if they completed the survey at T5. In general, participants received no compensation for taking part in the study. However, the students who participated received partial course credit for completing the questionnaires.

Previous mindfulness experience was assessed by asking participants at which frequency they had experienced any form of meditation (e.g., yoga, tai chi) in the 6 months prior to the study. About a quarter of the participants (28%) reported that they meditated at least twice a month, while the rest meditated less than once a month. Of those with meditation experience, about a quarter had experience with mindfulness meditation, specifically. About two fifths of the sample performed Yoga or other meditative movements at least twice a month in the last 6 months. There were no significant differences in meditation experience between the intervention and waitlist control groups. Moreover, there was no significant correlation between experience with meditative movement/Yoga and mindfulness measured at each time point (except at T1: Yoga and mindfulness: r = .14, p = .049).

Design and Procedure

Design

The study was conducted using a 2 (group: mindfulness intervention [IG] vs. waitlist control group [CG]) x 5 (time points)-mixed design. The intervention period between the pre-test (T1) and post-test (T5) was 4 weeks. Participants of both groups were also invited to complete weekly questionnaires (T2, T3, and T4). After the four-week intervention, the CG went through the intervention, while participants of the IG could continue with additional weekly changing mindfulness exercises.Footnote 3 We focus on a comparison between pre-test (T1) and post-test (T5) in our analyses of confirmatory hypotheses except for newly set goals (only T5) because we have no assumptions about the trajectory of change in the dependent variables. We only assume that there is a change between T1 and T5 in the intervention group. Additional exploratory analyses including all time points from T1 to T5 can be found in the Supplementary material on OSF. For the exploratory hypothesis on goal adjustment, we considered all time points directly.

Procedure

After registering, all participants completed the same baseline (T1) questionnaire in German via SoSci Survey (Leiner, 2019). They were assigned a serial number to allow matching of subsequent questionnaires. At the end of the first questionnaire, participants were randomly assigned to the intervention or waitlist control group. They received the respective information that they would start with the mindfulness intervention the next Monday (IG) or receive the intervention materials in the second intervention phase after four weeks (CG).

Mindfulness exercises changed on a weekly basis to enable participants to adjust to them while also preventing boredom through too much repetition. Each morning, participants in the IG received a link to the current exercise of the week via email. The first mail of each week contained information about the exercise of the week. The exercises were deposited as audio files in a survey project in SoSci-Survey. At the beginning of each exercise session, participants could choose between four voices (two male, two female) that led through the exercise. The exercises could be performed at any time of the day and were tailored to naïve participants. At the end of the mindfulness session, participants could leave a comment. Participants could contact the first author via email if any questions came up.

Mindfulness exercises

The mindfulness exercises were created by Kirsten Tofahrn, a certified Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction instructor and Mindful Self-Compassion teacher and director of the Mindfulness Center Cologne (Tofahrn, 2020). We received her permission to use the audio exercises freely available on her Internet webpage for our intervention. For each exercise, additional voices (two male, one female) were recorded to cater to personal taste. The following meditations were selected for the four-week mindfulness program in the following order: Body scan, Mindfulness of Breath, Loving Kindness to Self, and Walking Meditation (the audio files are stored on OSF). The exercises lasted between 9 and 12 min and were performed while lying down, sitting, standing, or walking, depending on the exercise. To establish a routine, the same exercise was provided daily for one week. We recommended carrying out the mindfulness exercise at the same time each day to facilitate building a routine. Nevertheless, this was only a suggestion and we still expected positive effects if carried out less frequently (Zhang et al., 2020). Participants were asked at the end of each week on how many days they had completed the exercise (Mweek1 = 5.3 days, SD = 1.3, n = 104; Mweek2 = 5.0 days, SD = 1.8, n = 87; Mweek3 = 4.9 days, SD = 1.6, n = 77; Mweek4 = 4.0 days, SD = 1.9, n = 79). Overall, participants enjoyed the exercises and experienced them as helpful (for an overview, see Table S1 in the supplementary material).

Measures Footnote 4

Already set personal goals

Personal goal description

At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were asked to list three important personal goals that they were currently pursuing. They received a short definition of personal goals and examples based on a description of Koestner and colleagues (2002; see Supplementary Material “List of measures” on OSF for a detailed description). At each subsequent measurement point, participants were asked if they were still pursuing the goal, had attained the goal, or had abandoned the goal. This was done for each goal individually. Goal-related questions were only asked if the participant reported continued goal pursuit. About one third of all goals could be categorized as being related to work/study. One third of the goals could be categorized as focusing on personal development. Goals also targeted social, health, and leisure aspects, but to a smaller extent. Overall, most goals were phrased in a rather abstract way. About 40% of the goals would no longer be pursued once they were achieved (e.g., passing an exam). For a more detailed description of goal coding, see Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Goal attainability and goal importance

For each goal, at each time point, participants were asked to indicate the goal’s current perceived attainability (very difficult to attain - very easy to attain) and importance (not at all important - extremely important) of the respective goal on a slider ranging from 1 to 101.

Goal progress

Goal progress was assessed with three items for each goal (e.g., “I have made a lot of progress toward this goal.”; Holding et al., 2017; Werner et al., 2016). Participants were asked to rate them on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Goal progress was aggregated across the three goals at each relevant time point for our main hypotheses. Cronbach’s alphas were αT1 = 0.77 and αT5 = 0.79.

Goal motivation

Goal motivation for each personal goal was assessed at T1 and T5 using the “perceived locus of causality” of personal goals and strivings (PLOC; Ryan and Connell, 1989) methodology (Sheldon, 2014). Participants rated the extent to which they pursued their goal for different reasons (i.e., motivation) on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. As in previous research, autonomous and controlled goal motivation were calculated separately (Koestner et al., 2008; Sheldon & Elliot, 1998). Autonomous motivation was calculated as the mean of one item measuring intrinsic (“Because it is fun or interesting to do it”) and one item measuring identified (“Because I truly value it”) motivation. Controlled motivation was calculated from the mean response to two items measuring introjected (“Because I would feel ashamed, guilty, or anxious if I did not”; “To help me look good to others”) and one item measuring external motivation (“Because other[s] want me to, or pressure me to”). Autonomous and controlled motivation measures were aggregated across the three goals for the analyses for each time point. The aggregated measures had Cronbach’s alphas of αT1 = 0.70, αT5 = 0.69, αT1 = 0.79, and αT5 = 0.87, respectively.

Newly set goals

Personal goal description

At each time point beginning at T2, participants were also asked to indicate if they had set a new goal according to the same definition given for goals at the beginning of the study (Koestner et al., 2002). At T2, they were only asked for a new goal if one of the previous goals was abandoned; beginning from T3 they were always asked if they had set a new goal.

Goal motivation

Participants were also asked for their reasons for goal pursuit if they had indicated that they had set a new goal (same method as with already set goals). Scores for each reason were averaged across time points. Autonomous motivation for new goals was calculated as the mean of intrinsic and identified reasons (r = .73) and controlled motivation for new goals was calculated as the mean of external and introjected reasons (α = 0.75).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was measured using the full and short, 5-item, German version of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown and Ryan, 2003; German validation of Michalak et al., 2008). The 15 items of the scale are formulated in a way to indicate a lack of mindfulness (e.g., I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present.; I find myself doing things without paying attention.). Items were answered on a 6-point Likert scale indicating the frequency of mindfulness (1 = almost always to 6 = almost never). Higher values indicate higher mindfulness. At T1 and T5 we used the full scale. At T2, T3, and T4 we employed the 5-item short version of the MAAS. The internal consistency of the scale was good to very good, with αT1 = 0.85 and αT5 = 0.90.

Well-being

At each time point, participants were asked to indicate how they felt during the last week. They reported their affect (very bad – very good) and arousal (very tense – very relaxed) on a slider ranging from 1 to 101. The mean of both items was used to indicate well-being at each relevant time point for the main hypotheses (correlation between both items: rT1 = 0.72 and rT5 = 0.70; listwise n = 163; pairwise similar values).

Perceived stress

The modified German version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983; German version: Schneider et al., 2020) was used to measure perceived stress at each time point. Participants rated the frequency of specific thoughts or feelings during the previous week on a 5-point Likert-type scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often; e.g., How often did you feel nervous or stressed out?). Four items were reverse-coded. In our sample, Cronbach’s alphas were αT1 = 0.87 and αT5 = 0.90.

Results

All data reported in this study are available online via the Open Science Framework, hosted on the mindfulness and goal regulation processes project page.

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive characteristics of the variables at baseline are shown in Table 2. Mean mindfulness was comparable to that of previous studies (Marion-Jetten, Taylor, & Schattke, 2022; Moszeik et al., 2022; Smyth et al., 2020). Cross-sectionally, mindfulness was negatively associated with stress and positively with well-being. Moreover, being more mindful was linked to greater goal-progress, reporting more autonomous motivation and less controlled motivation. Finally, autonomous motivation was positively correlated with goal progress, while controlled motivation was non-significantly negatively associated with the latter.

Each variable was analyzed regarding possible pre-test differences between groups (Table S3, Suppl. Material). A significant difference was only found for well-being, t(223) = -2.06, p = .041. Participants in the intervention group reported a lower level of well-being at baseline compared with the control group.

When analyzing the status of each goal the last time a participant provided data, 93% of participants reported still pursuing their first goal, 88% still pursued their second goal, and 85% still pursued their third goal. 3% had abandoned goal pursuit of their first goal, 5% their second goal, and 11% had abandoned their third goal. Accordingly, only a few participants attained their goals over the course of the study. Of those who answered the questionnaire at T5, 98% still pursued their first goal, 94% their second goal, and 95% their third goal. There was no difference between the groups in continued goal pursuit, X22) < 1.67, ps > 0.429. Moreover, they did not differ in the summed number of abandoned or attained goals, X2(2) < 1.50, ps > 0.519.

Hypotheses testing

Intervention effect on mindfulness, well-being, and stress

To test the intervention effect on mindfulness, well-being, and stress, we applied latent change score models (McArdle, 2009) using Mplus version 8.1.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Change is modelled directly as a latent difference variable in these models. While the mean of the latent change variable indicates average change between the respective time points, the variance of the change variable captures between-person differences in within-person change. We tested the change between baseline (T1) and after four weeks of intervention (T5). The latent change factor (ΔT5 − T1) for each variable was defined by its respective value at T5 with the loading set to one. The autoregressive path to baseline was set to one. Means and residual variances of the relevant variable at T5 was restrained to zero. Covariances between T1 and latent change variables were estimated freely. The models were estimated using robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR). We estimated models on the basis of all available data points using the full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML, Arbuckle, 1996) implemented in Mplus under the missing-completely-at-random assumption (Little & Rubin, 1987).

For each dependent variable (mindfulness, well-being, and perceived stress), we tested the intervention effect in a series of model comparisons with stepwise relaxation of constraint assumptions for equality of groups for each variable separately (i.e., testing invariance between the control and intervention group in the framework of multigroup models). In each Model 1, for both groups we assumed equality of means, variances, and covariance between baseline and change, that is, we tested a model that is invariant over groups. However, given the group difference in well-being at baseline, we allowed the mean to vary between groups at baseline for this variable. In a subsequent model, we relaxed the assumption of equal means of the latent change variable (Model 2), that is, we tested whether a model with different change coefficients produces a better model fit. This model allows the test of the hypothesized intervention effects. Finally, we exploratorily tested a model in which the variance of the latent change variable as well as covariance between baseline and latent change was allowed to vary between groups (Model 3). Significance of change in model fit was determined using chi-square difference tests based on scaling correction factors obtained with the MLR estimator (Satorra & Bentler, 2010). We only report the findings of each Model 2 in the article because they are most relevant for testing the hypotheses. Coefficients for Model 2 are displayed in Table 3. Each Model 2 showed significant increase in model fit compared to Model 1. Model 3 did not result in a significant increase for each variable. Model coefficients for all models are reported in Tables S5-S8 in the Supplementary Material. We report effect sizes and their 95% confidence interval for within-group changes using a tool provided by Lenhard and Lenhard (2016) based on a formula that uses the pooled standard deviation, controlling for the intercorrelation of both time points, referred to as dRM, pool. We also conducted analyses including all measurement points to explore the trajectories of change and potential group differences implementing baseline versions of the latent change score models (Steyer et al., 1997, 2000; see Suppl. Material for Figures S9a-S9c and mplus outputs).

Mindfulness

Model 2 (see Table 3) showed satisfactory model fit (see Figure S6 in Supplementary Material). There was a small significant increase in mindfulness in the control group, estimate = 0.10, p = .049, dRM, pool = 0.27, 95% C.I. [0.01; 0.52]. This effect was markedly larger in the intervention group, estimate = 0.40, p < .001, dRM, pool = 0.86, 95% C.I. [0.59; 1.13]. This finding is in line with Hypothesis 1a that mindfulness increases more in the intervention compared to the control group (see Fig. 1a).

Well-being

In accord with the Hypothesis 1b, Model 2 (see Table 3) demonstrated a group difference in change in well-being over four weeks (see Fig. 1b). Well-being significantly increased in the intervention group, estimate = 14.45, p < .001, dRM, pool = 0.40, 95% C.I. [0.13; 0.66]. In contrast, there was no significant change in well-being in the control group, estimate = 3.51, p = .194, dRM, pool = 0.11, 95% C.I. [-0.15; 0.36]. The model fit was very good.

Stress

As expected (Hypothesis 1c), perceived stress significantly decreased in the intervention group, estimate = -0.31, p < .001, dRM, pool = -0.47, 95% C.I. [-0.74; -0.20]. In contrast, there was no significant change in the control group, estimate = -0.08, p = .224, dRM, pool = -0.11, 95% C.I. [-0.37; 0.15]. This model showed very good model fit.

Intervention effects on goal regulation measures

Change in goal progress

We examined change in goal progress between baseline and post intervention as a function of the mindfulness intervention as well as autonomous goal motivation at T1, and their interaction using a latent change score model. We first implemented a model invariant over groups. Goal progress as well as autonomous goal motivation were averaged across goals. Autonomous goal motivation (mean centered) was included as a predictor of the baseline level of goal progress as well as its change. In a second model, the mean of the latent change variable was allowed to vary between groups. In a third model, the regression coefficients for the effect of goal motivation could also vary between groups. Moreover, the variance of the change as well as of the covariance were allowed to vary between groups. All model coefficients are reported in Table S10 in the Supplementary Material.

The second model showed a very good model fit, X2(6) = 6.27, p = .393, RMSEA = 0.020 [90% C.I. = 0.000; 0.125], CFI = 0.99 (Figure S11 in Supplementary Material). It demonstrated increased model fit compared to the first model, Satorra-Bentler scaledΔX2(1) = 4.57, p = .033. In line with Hypothesis 2, goal progress significantly increased in the intervention group, Estimate = 0.29, p = .008, dRM, pool = 0.23, 95% C.I. [-0.04; 0.49], whereas there was no significant change in the control group, Estimate = -0.03, p = .772. Moreover, while autonomous goal motivation was positively associated with goal progress at baseline, Estimate = 0.33, p < .001, there was no significant effect of autonomous goal motivation on change in goal progress (H3 and H4), Estimate = 0.01, p = .932 (in Model 3: EstimateCG = -0.11, p = .414; EstimateIG = 0.15, p = .174). The third model did not show a better model fit than the second model, Satorra-Bentler scaled ΔX2(3) = 6.04, p = .109. Exploratorily conducting these analyses with the second model (i.e., allowing the mean of the latent change variable to vary between groups) for each goal separately showed the same pattern of results (see OSF project for mplus outputs).

Goal motivation in newly set goals

Overall, only a small number of participants reported that they had set a new goal. In the intervention group, 27 participants reported setting at least one new goal during the intervention phase, while 38 participants in the control group did so. To test differences between groups in goal motivation for newly set goals, we computed autonomous and controlled goal motivation for each newly set goal and averaged goal motivation across measurement points if participants reported a newly set goal at more than one measurement occasion. As hypothesized (Hypothesis 5), participants in the intervention group (M = 5.8, SD = 1.2) reported significantly higher autonomous goal motivation than those in the control group (M = 5.0, SD = 1.7), Welch’s t(63) = 2.37, p = .021, Hedges’ d = 0.55. In contrast, there was no significant group difference in controlled motivation for newly set goals, t(63) = 0.65, p = .521 (IG: M = 2.5, SD = 1.3; CG: M = 2.3, SD = 1.3).

Change in goal importance

To exploratorily predict the interactive effects of mindfulness, goal attainability at T1, changes in goal attainability across time, and autonomous goal motivation at T1 on changes in goal importance, we used linear mixed-effects models as implemented in the lme4-package (Bates et al., 2015) in the R System for Statistical Analysis (R Core Team, 2021).Footnote 5 Such multilevel analyses enable the analysis of longitudinal hierarchical data. That is, variables can be nested within another, such that time, baseline goal attainability, changes in goal attainability (over the study period), and goals could be nested within participants to determine their influence on goal importance (changes) over time. The level of the variables represents within which other variable they are nested. The data were nested in this way: time (coded as a linear effect from T1 to T5, centered to the mean time point T3) was at level 1 and nested within goals at level 2. Goals, centered with the first goal serving as the baseline (contrast centering derived via the hypr-package in R; Schad et al., 2020; Rabe et al., 2020), were themselves nested within participants at level 3. As such, this analysis allowed changes in goal importance over timeFootnote 6 to be modeled from baseline goal attainability (averaged across goals for each participant and standardized), baseline autonomous motivation (averaged across goals per participant and standardized), changes in attainability over the study period (estimated via a linear mixed-effects model on attainability scores with fixed effect linear time and random linear time slopes across participants; the random slope regression coefficient per participant was used) and group (control group was coded as 0, and intervention group as 1).

Our linear mixed-effects model included two fixed effects four-way interactions. The first was an interaction between attainability at T1, time, group, and autonomous goal motivation at T1. The second was an interaction between change in attainability from T1 to T5, time, group, and autonomous goal motivation at T1. We also ran all the lower-level interactions of these four-way interactions. The fixed effects interaction between time and goal (contrasting goal 2 vs. 1, and goal 3 vs. 1) as well as that between time and goal importance across goals at T1 were included in the model as controls. Our model also included the random intercepts and uncorrelated random slopes for time, goals, and the interaction of time by goals for each participant to allow for different starting points in terms of goal importance for each participant and goal, while also letting it vary over time for each person.Footnote 7

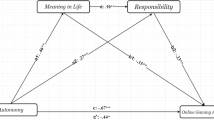

The results from the linear mixed-effects model are displayed in Table A1 (Appendix). The four-way interaction between baseline attainability, time, group, and autonomous goal motivation at T1 was significant (b = 1.05, SE = 0.42, df = 239.70, t = 2.47, p = .014)Footnote 8. To follow up on this interaction, we tested the three-way interaction between attainability at T1, time, and autonomous goal motivation nested within each group to predict changes in goal importance over time. The three-way interaction was significant for the control group (b = -0.70, SE = 0.27, df = 232.39, t = -2.56, p = .011) but not for the intervention group (b = 0.32, SE = 0.32, df = 248.99, t = 1.00, p = .316). To further qualify those results, we performed a median split to create a group of more autonomous (vs. less) autonomous goals, thus creating four groups by differentiating between the intervention vs. control group, and between more (vs. less) autonomous goals. We tested an interaction between time and goal attainability at T1 within each of the four subgroups. The results showed that the time by attainability at T1 interaction was significant for the subgroup of control group participants who had less autonomous goal motivation (b = 1.45, SE = 0.43, df = 219.61, t = 3.35, p = .001), but not for those with more autonomous goal motivation (p = .629), nor for participants in the intervention group (regardless of whether their goals were more/less autonomously motivated: p = .668/0.976). Figure 2 displays the results from those interactions. It shows that goal importance declined overall from T1 to T5 (negative goal importance change). The results suggest that this decline was larger for goals with low versus high baseline attainability, but only for participants in the control group with less autonomous goals. That is, levels of goal attainability at baseline were only related to changes in goal importance for participants in the control group with less autonomously motivated goals.

Goal importance change from T1 to T5 (linear regression coefficients) per participant was estimated as random slopes in a linear mixed-effects model. Note The negative scale for goal importance change indicates the overall decrease across time. As such, a positive slope indicates a smaller decrease in goal importance

The second four-way interaction tested within our model was between change in attainability across time (from T1 to T5), time, group, and autonomous goal motivation at T1. This interaction was significant (b = 1.15, SE = 0.40, df = 197.54, t = 2.89, p = .004)Footnote 9. To disentangle the interaction, we ran follow up analyses. We found a significant three-way interaction of time by change in attainability over time by autonomous goal motivation in both the control group (b = -0.67, SE = 0.32, df = 205.68, t = -2.11, p = .036) and the intervention group (p = .48, SE = 0.24, df = 188.10, t = 2.00, p = .047), but with regression coefficients with opposite polarity. Again, we separated goal autonomous motivation at the median split and tested a two-way interaction of time by change in attainability for the four subgroups (defined by intervention vs. control group, and by more vs. less autonomous goals). The two-way interaction was significant with a positive regression coefficient in each of the four groups (p-values < 0.011), suggesting that participants with a stronger increase in goal attainability over time showed a smaller decrease of goal importance over time, whereas participants with little change in goal attainability showed a stronger decrease of goal importance. However, the size of the regression coefficients for this effect differed between more versus less autonomous goals depending on group. In the control group, this effect was stronger for participants with less autonomous goal motivation (b = 2.12, SE = 0.49, df = 215.77, t = 4.29, p < .001) than for participants with more autonomous goals (b = 1.03, SE = 0.40, df = 199.25, t = 2.58, p = .011), whereas the reverse was true for the intervention group, with a stronger effect for participants with more autonomous goals (b = 1.00, SE = 0.39, df = 181.53, t = 2.58, p = .011) than for participants with less autonomous goals (b = 2.25, SE = 0.47, df = 183.79, t = 4.78, p < .001).Footnote 10

Goal importance change from T1 to T5 (linear regression coefficients) per participant as well as goal attainability change from T1 to T5 (linear regression coefficients) per participant were estimated as random slopes in linear mixed-effects models. Note The negative scale for goal importance change indicates the overall decrease across time. As such, a positive slope indicates a smaller decrease in goal importance

Discussion

The present research investigated the effects of an online mindfulness meditation intervention on goal progress and goal importance for current personal goals, and goal motivation for new goals.

Effects on mindfulness, well-being, and stress

To determine potential effects of the mindfulness intervention, we first tested its effectiveness as a manipulation check. In line with previous studies using online mindfulness interventions, our intervention was successful in increasing mindfulness and subjective well-being as well as in decreasing subjective stress (Lahtinen et al., 2021; Moszeik et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020). Mindfulness increased by almost one standard deviation. Moreover, the intervention had a moderate effect on increasing well-being and decreasing stress. These findings support the notion that even a short mindfulness intervention implemented relatively regularly can be effective.

Interestingly, exploratory analyses of the trajectory of change in mindfulness showed that mindfulness first decreased in both groups and then slowly increased again. Participants in the control group returned to their baseline level, whereas participants in the intervention group achieved higher levels of mindfulness at the end of the intervention (see Figure S9a for a visualization). Given that the groups did not differ in their decrease in mindfulness in the beginning, this decrease might rather be an effect of being asked about mindfulness and then paying more attention to potential situations signaling (lack of) mindfulness (Levinson et al., 2014; cf. response-shift effect, Howard, 1980). Participants might then have realized that they have previously overestimated their mindfulness resulting in lower values at T2, that is, they might have changed their internal standard. Bartos et al. (2023) demonstrated that such changes in the frame of reference for self-report measures can underestimate the actual effect of a mindfulness intervention. Later on, both groups in the present study might have worked on increasing mindfulness in their daily life, but only the intervention group received exercises to increase their mindfulness. Moreover, in the present study, well-being increased and stress decreased in both groups from T1 to T2, but only the intervention group continued this trajectory. While at the beginning both groups might have psychologically benefitted from the prospect of taking part in a study aimed at their well-being, only the intervention group took part in the exercises supporting their well-being and decreasing stress, whereas the control group had to wait. Overall, there was a large variance in change within groups pointing to various extraneous factors influencing the extent and possibly the trajectory of change. Future studies could take a closer look at the trajectory and other potential factors (e.g., perception of support from close ones), because these could also be relevant for the effect on goal regulation processes.

Effects on goal regulation

Cross-sectional findings

In terms of goal regulation, the cross-sectional results of the present study replicate previous findings on the relations between mindfulness, goal motivation, and goal progress. Mindfulness was positively associated with autonomous goal motivation and negatively so with controlled goal motivation, mirroring past research on this topic (Donald et al., 2020; Marion-Jetten et al., 2022b; Ryan et al., 2021). Moreover, it was positively associated with goal progress (Smyth et al., 2020; Spence & Cavanagh, 2019). Corroborating previous findings, autonomous goal motivation was also positively correlated with goal progress (Koestner et al., 2008; Werner et al., 2016) and there was no significant relation between controlled goal motivation and goal progress (Koestner et al., 2008).

Goal progress

To further substantiate these correlational findings with experimental data, we conducted a mindfulness intervention study. We found a small to moderate effect on goal progress in the mindfulness intervention but not in the control group. That is, our findings extend previous correlational data (Smyth et al., 2020; Spence & Cavanagh, 2019) by showing that increasing mindfulness promotes goal progress. Mindfulness interventions endorse attention on, and a non-judgmental reflection of internal and external events (Bishop et al., 2004; Ryan et al., 2021). As such, it might foster goal monitoring processes, especially when people are asked about their goal progress on a weekly basis. In their meta-analysis, Harkin et al. (2016) reported a positive effect of goal progress monitoring interventions on the monitoring itself, as well as goal attainment. Moreover, the attention to momentary states promoted by mindfulness might also strengthen or shift people’s focus to the process of goal pursuit, in contrast to focusing on its outcome. Indeed, focusing on processes has been shown to be conducive to goal pursuit and well-being (Freund & Hennecke, 2015; Krause & Freund, 2016). Mindfulness might also help people accept their negative emotions and regulate them more effectively, while also giving them the opportunity to notice and feel their positive emotions and be able to move on to focusing on their goals after an obstacle. In other words, it is possible that mindfulness makes people more action (vs. state) orientated. Indeed, some preliminary correlational research shows that dispositional mindfulness is positively associated with action orientation in university students (Taylor & Marion-Jetten, 2020). Nonetheless, given the present study’s short time span, future studies should examine the effects of longer-term interventions. Moreover, future studies should investigate the processes by which mindfulness increases goal progress in more detail.

Autonomous goal motivation is another factor relevant for goal progress (Koestner et al., 2008; Werner et al., 2016). While autonomous goal motivation was positively associated with goal progress cross-sectionally in this study, it was not predictive of change in goal progress. That is, there was neither a general effect of autonomous goal motivation, nor did the mindfulness intervention moderate its effect on goal progress. Two aspects might help explain this. First, personal goals reported in the present study were, on average, highly autonomously motivated with only a small variance. Therefore, increases in goal progress might actually be the result of high autonomous goal motivation, but its effect might not be detectable due to its small variance. Second, previous correlational studies investigated the effect of autonomous goal motivation for personal goals on a larger time scale. Thus, its supporting effect might only become visible after a longer period for personal goals.

Goal setting

Mindfulness has also been associated with setting more autonomously motivated goals (Grund et al., 2018; Smyth et al., 2020), that is, they perceive their goals to be more in line with their core values or being of interest to them and joyful. Therefore, we examined the effect or our mindfulness intervention on goals that were set over the course of the study. We obtained a moderate-sized effect supporting the influence of mindfulness in setting autonomous goals. More specifically, participants in the intervention group set goals with similarly high levels of autonomous motivation as those that they had previously pursued (i.e., those they initially reported on in the study). In contrast, participants in the control group set less autonomous goals as compared to those they had when they started the study. Our findings align with the hypothesis that mindfulness helps buffer against external pressures (Schultz & Ryan, 2015). Indeed, our sample contained a strong student proportion (58%) and our study coincided with the end of the semester, a stressor associated with external pressures such as tests and assignment deadlines, known to promote controlled motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Yet, participants in the intervention group were still able to set more autonomous goals in this pressure situation, thus supporting the argument that mindfulness can provide a buffer against being “unconsciously triggered by extrinsic rewards and punishments or threats to the self” (Donald et al., 2020, p. 1133).

Goal importance

Finally, we explored the influence of mindfulness in interaction with goal attainability and autonomous goal motivation on goal importance changes as one of the goal adjustment processes (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002). The analysis revealed that participants in the control condition with less autonomously motivated goals showed changes in goal importance over the study period in response to their goals’ attainability at baseline (that is, already ongoing processes); lower attainability was related to the strongest decrease in goal importance. In contrast, participants in the mindfulness group did not show such an effect. On the one hand, reduction of goal importance in response to less attainable goals can be seen as a coping response to preserve resources, focus on more promising goal pursuit, and maintain well-being (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002; Heckhausen et al., 2010). Participants in the control group might have sensibly responded to lower attainability of their less autonomous goals, whereas mindfulness hampered this process. On the other hand, there is the risk of premature compliance with constraints and adjustment of goals. Participants in the control group with less autonomous goals might give up too easily and adjust their goal pursuit, whereas mindfulness might have promoted emotion regulation strategies such as positive reappraisal to support coping with frustration in goal pursuit (Garland et al., 2015; Marion-Jetten et al., 2022a). Therefore, participants in the intervention group may have been able to ‘stick’ with those less autonomous goals of low attainability and maintain their importance over time. This aligns with Marion-Jetten et al. (2022b) finding that mindfulness negatively predicted goal disengagement over time.

At the same time, there was no change in goal importance for more autonomous goals regardless of their perceived attainability at baseline for participants in both groups, indicating that more autonomous goals may be harder to devalue even when they are less attainable. This finding corroborates the result of Ntoumanis et al. (2014) in an experiment where participants reported less cognitive ease in letting go of unattainable autonomously motivated goals. Indeed, while highly autonomous goals are usually seen as positive, they may drive a person towards a major crisis (e.g., action crisis) when they are becoming less attainable, especially if the goal is central to one’s identity (e.g., career goals; Brandtstädter and Rothermund, 2002).

However, the analysis also revealed that participants adjusted goal importance in response to changes in goal attainability across the study period for less autonomous as well as more autonomous goals. Increasing attainability was related to smaller decreases in goal importance, while no/little change in attainability was associated with stronger decreases in goal importance. The average decrease in goal importance in this study might indicate regression to the mean to some extent due to asking for participants’ important personal goals at the beginning. Still, the relationship between attainability change and goal importance change reflects their interdependency (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002). Interestingly, participants in the control group showed a similar pattern as when we considered only baseline attainability. That is, they showed the highest reduction in goal importance for less attainable and less autonomous goals. In the intervention group, participants showed smaller decreases in goal importance when the attainability of more autonomously motivated goals increased. The mindfulness intervention might have particularly emphasized goal pursuit for autonomously motivated goals (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Ryan et al., 2021) increasing their importance over time when they become more attainable (potentially also investing more effort into them to render them more attainable). At the same time, when attainability stagnated (i.e., showed little to no change over the course of the study), more autonomously motivated goals saw a reduction in their importance in the mindfulness group. Interestingly, more autonomous, less attainable goals were devalued to a greater extent than less autonomous, less attainable ones. A possible explanation may be that participants in the mindfulness condition might have differentiated between goals they fully endorsed and felt agency upon (more autonomous goals) vs. goals that may be closer or likened to obligations towards others or oneself (less autonomous ones). As such, they may have felt they could not reduce the importance (to eventually let go) of less attainable and less autonomous goals but could do so for less attainable, more autonomous ones. This argument aligns with the finding by Holding et al. (2022) that people autonomously motivated to disengage avoid inaction crises and make more progress towards disengagement. Perhaps, mindfulness promotes such ‘autonomous disengagement’ for more autonomous goals. However, this finding is in contrast to Ntoumanis et al. (2014) where participants felt less cognitive ease in letting go of unattainable autonomously motivated goals.

It will be interesting for future studies to experimentally manipulate goal attainability of varying degrees and changes in attainability (including permanent and temporary goal blockage; Mayer and Freund, 2022; Rühs et al., 2022) to attempt to replicate, and better understand, these results as well as their short- and long-term consequences (e.g., under which conditions does mindfulness promote persistence for less autonomous, less attainable goals, how long do more mindful people persist before reducing the importance of more and less autonomous goals and is it always adaptive).

Limitations and future directions

Although the present study has its strengths in investigating the effect of mindfulness in an experimental and ecologically valid setting, there are some limitations concerning the conclusions. First, using self-report measures has the disadvantage of socially desirable or self-deceptive responding. Second, we used a waitlist control group design instead of an active control group. This has the caveat that obtained effects might be the result of an intervention per se but not particularly due to our mindfulness intervention. The fact that mindfulness first decreased in both groups but then increased particularly in the intervention group (besides an increase in well-being and decrease in stress) can, to some extent, appease this concern for our study. Unfortunately, it is difficult to disentangle possible differential effects of the exercises from time and cumulative effects. We implemented different exercises on a weekly basis, but in the same order. The exercises were structured in such a way that the level of complexity increased with each new exercise in order to familiarize non-experts with mindfulness and to build it up slowly.

We also conducted a four-week follow-up data collection but were only able to obtain data from about half of the sample. Longer-term interventions with larger samples to enable fully powered analyses of such follow ups are needed to better understand the influence of mindfulness on goal regulation processes.

Given that the study was conducted during the pandemic, we assumed that participants would be confronted with many obstacles in goal pursuit (Fisher et al., 2020; Nikolaidis et al., 2022; Ritchie et al., 2021). However, although only very few goals were attained during the course of the intervention phase, very few participants actually abandoned their goals (cf. Hubley and Scholer, 2022). Moreover, autonomous goal motivation was quite high suggesting that participants were still able to set and focus on goals close to their heart. Yet, in order to investigate goal adjustment processes and its interplay with mindfulness and goal motivation, a greater variance in severity of goal constraints as well as goal motivation would be desirable. In the same vein, only a few participants reported setting new goals during the course of the study. Given that most participants still pursued their three goals set at the beginning of the study, this might not be surprising. However, participants might also have underreported their new goals to prevent further questioning. In a future study, we could only ask about setting a new goal once at the post-intervention assessment.

Conclusions

This longitudinal experimental design investigated the effect of a mindfulness intervention on goal processes. It replicated established findings regarding the associations between mindfulness and autonomous and controlled goal motivation. It also showed that mindfulness promoted goal progress and setting autonomously motivated goals. These results provide causal support for many correlational relations previously found between mindfulness and goal regulation processes. Our findings also provide early evidence for the role of mindfulness and autonomous goal motivation in goal adjustment processes.

Notes

The term goal disengagement has been used very inconsistently in the literature (for a discussion, see Kappes & Greve, 2023; Kappes and Schattke, 2022). For example, Brandtstädter and Rothermund (2002) use this term denoting the process of dissolving commitment to a goal but also as the result of goal adjustment processes (accommodative coping). Moreover, it seems that they employ the term goal disengagement interchangeably with one process of goal adjustment, namely devaluing importance. In general, goal disengagement and goal adjustment in their work mainly refer to cognitive-affective processes and less to cessation of (behavioral) goal pursuit as an expression of goal disengagement. Importantly, processes of goal disengagement or, more generally goal adjustment, are assumed to operate without intention (p. 118/123). Heckhausen et al. (2010) describe compensatory secondary control processes as processes being involved in goal disengagement. These include distancing from the goal (e.g., devaluing the chosen goal and downgrading its importance, enhance value of conflicting goals), and self-protection (e.g., downward comparisons, self-serving attributions of failure). In Wrosch et al. (2003), the aforementioned processes are theorized as facilitating goal disengagement while goal disengagement is a process of its own. In the present study, we use the broader term goal adjustment processes to denote processes related to coping with futile or too resource-consuming goal pursuit. We focus on one particular process, adjustment of goal importance.

There were also no differences at T1 concerning mindfulness (p = .389), well-being (p = .387), and stress (p = .058) between those who provided data at T5 compared to those who did not when taking group as covariate into account. One participant did not provide data on stress at T5. We also tested potential differences of these subsamples separately in the control and intervention group and did not find any significant differences, ps > 0.113 (see Table S4 in the supplementary material).

Four weeks after the post-test, a follow-up survey was administered; however, this is not part of the analyses due to only a small number of retained participants (IG: n = 50; CG: n = 61).

a full list of collected variables of this study is available on OSF

We only focused on autonomous goal motivation because there are overall more consistent findings for this type of goal motivation. Moreover, controlled goal motivation was very low in the present sample. Still, we report a structurally same analysis including controlled goal motivation (instead of autonomous goal motivation) in Table S12 in the Supplementary Material.

We also tested whether goal importance, our dependent variable, was normally distributed. We found that a quadratic transformation of the variable yielded a closer approximation of the normal distribution (Box & Cox, 1964; estimated via the MASS-package in R). As such, we used squared goal importance as the dependent variable in a control analysis, which yielded the same results as the one described below (see Supplementary Material for Table S13 with all coefficients).

Given that this is an exploratory analyses, we did not calculate an a priori power analysis. We provide a sensitivity analysis to detect a 4-way interaction effect in the supplementary material.

We also compared a model including the 4-way interaction term with a model without this term. While the AIC was in line with the frequentist statistics (AICwith: 22,413 vs. AICwithout: 22,417), the BIC slightly favored the reduced model, but was inclonclusive (BICwith: 22,637 vs. BICwithout: 22,635).

We again compared a model including the 4-way interaction term with a model without this term. This comparison yielded the same finding that the AIC was in line with the frequentist statistics (AICwith: 22,413 vs. AICwithout: 22,420), the BIC was inconclusive, but also slightly in favor of the frequentist statistics (BICwith: 22,637 vs. BICwithout: 22,638).

Based on a reviewer’s suggestion, we also tested a model, in which goal attainability was included as a time-varying covariate instead of testing baseline and change in attainability. This model also provided a significant interaction effect between goal attainability, autonomous goal motivation, and group. Statistical findings are reported in the supplementary material.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides, & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baltes, P. B. (1997). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American Psychologist, 52(4), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.4.366.

Barlow, M. A., Wrosch, C., & McGrath, J. J. (2020). Goal adjustment capacities and quality of life: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality, 88(2), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12492.

Bartos, L. J., Posadas, M. P., Wrapson, W., & Krägeloh, C. (2023). Increased effect sizes in a mindfulness- and yoga-based intervention after adjusting for response shift with then-test. Mindfulness, 14(4), 953–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02102-x.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLIPSY.BPH077.

Box, G. E. P., & Cox, D. R. (1964). An analysis of transformations (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B, 26, 211–252.

Brandstätter, V., & Bernecker, K. (2022). Persistence and disengagement in personal goal pursuit. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-110710.

Brandstätter, V., & Schüler, J. (2013). Action crisis and cost–benefit thinking: A cognitive analysis of a goal-disengagement phase. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.004.

Brandtstädter, J., & Greve, W. (1994). The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review, 14(1), 52–80. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1994.1003.

Brandtstädter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process Framework. Developmental Review, 22(1), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2001.0539.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298.

Brown, K. W., Goodman, R. J., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Dispositional mindfulness and the attenuation of neural responses to emotional stimuli. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss004.

Brunet, J., Gunnell, K. E., Gaudreau, P., & Sabiston, C. M. (2015). An integrative analytical framework for understanding the effects of autonomous and controlled motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 84, 2–15.

Brunstein, J. C., Schultheiss, O. C., & Maier, G. W. (1999). The pursuit of personal goals: A motivational approach to well-being and life adjustment. In J. Brandtstädter, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Action and self-development: Theory and research through the life-span (pp. 169–196). Sage.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Colzato, L. S., Ozturk, A., & Hommel, B. (2012). Meditate to create: The impact of focused-attention and open-monitoring training on convergent and divergent thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00116.

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL. https://www.R-project.org/.

Credé, M., Tynan, M. C., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Rosenvinge, J. H., Tyssen, R., Hanley, A., & Garland, E. (2018). Six-year positive effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on mindfulness, coping and well-being in medical and psychology students; results from a randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0196053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196053.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., & Kashdan, T. B. (2019). Is grit relevant to well-being and strengths? Evidence across the globe for separating perseverance of effort and consistency of interests. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 194–211.

Donald, J. N., Atkins, P. W. B., Parker, P. D., Christie, A. M., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). Daily stress and the benefits of mindfulness: Examining the daily and longitudinal relations between present-moment awareness and stress responses. Journal of Research in Personality, 65, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRP.2016.09.002.

Donald, J. N., Bradshaw, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Basarkod, G., Ciarrochi, J., Duineveld, J. J., Guo, J., & Sahdra, B. K. (2020). Mindfulness and its association with varied types of motivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis using self-determination theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219896136.

Duckworth, A. L., Taxer, J. L., Eskreis-Winkler, L., Galla, B. M., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Self-control and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103230.

Emmons, R. A. (1996). Striving and feeling: Personal goals and subjective well-being. In P. M. Gollwitzer, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 313–337). Guilford.

Fisher, J. R. W., Tran, T. D., Hammarberg, K., Sastry, J., Nguyen, H., Rowe, H., Popplestone, S., Stocker, R., Stubber, C., & Kirkman, M. (2020). Mental health of people in Australia in the first month of COVID-19 restrictions: A national survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 213(10), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50831.

Freund, A. M., & Hennecke, M. (2015). On means and ends. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(2), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414559774.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N., Goldin, P., & Fredrickson, B. (2015). The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1092493.

Ghassemi, M., Bernecker, K., Herrmann, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2017). The process of disengagement from personal goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216689052.

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered traits: Science reveals how meditation changes your mind, brain, and body. Penguin.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D. D., Shihab, H. M., Ranasinghe, P. D., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E. B., & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018.

Grund, A., Fries, S., & Rheinberg, F. (2018). Know your preferences: Self-regulation as need-congruent goal selection. Review of General Psychology, 22(4), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000159.

Haase, C. M., Heckhausen, J., & Wrosch, C. (2013). Developmental regulation across the life span: Toward a new synthesis. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029231.

Hafenbrack, A. C., Kinias, Z., & Barsade, S. G. (2014). Debiasing the mind through meditation: Mindfulness and the sunk-cost bias. Psychological Science, 25(2), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613503853.

Harkin, B., Webb, T. L., Chang, B. P. I., Prestwich, A., Conner, M., Kellar, I., Benn, Y., & Sheeran, P. (2016). Does monitoring goal progress promote goal attainment? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 198–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000025.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117(1), 32–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017668.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2019). Agency and motivation in adulthood and old age. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103043.

Heppner, W. L., Spears, C. A., Vidrine, J. I., & Wetter, D. W. (2015). Mindfulness and emotion regulation. In B. D. Ostafin, M. D. Robinson, & B. P. Meier (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 107–119). Springer.