Abstract

The morphological marking that distinguishes conditionals that are called “counterfactual” from those that are not, can also be found in other modal constructions, such as in the expression of wishes and oughts. We propose to call it “X-marking”. In this article, we lay out desiderata for a successful theory of X-marking and make some initial informal observations. Much remains to be done.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 The study of X-marking introduced

Two kinds of circumstances in which one might want to make a conditional claim are:

-

1.

when the antecedent proposition is epistemically possible (“open”) and one wants to convey that the consequent follows from the antecedent,

-

2.

when the antecedent proposition is known to be false (“counterfactual”) and one wants to convey that the consequent would have followed from the antecedent had it been true.

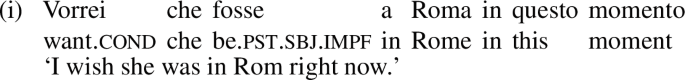

The linguistic expressions of open conditionals and counterfactual conditionals are typically distinct. For example, in English one would use the following pair of sentences in the two relevant circumstances:

The morphology in English of the conditional in (1b) differs from the morphology in (1a) in several ways: an extra layer of past tense in both clauses of (1b) and the presence of the modal underlying the expression would in the consequent.

There are at least two terms that have been used in the literature to refer to this morphosyntactic marking: “counterfactual” and “subjunctive”. The former is more common in linguistics, the latter in philosophy and logic. However, both terms are problematic.Footnote 1

1.1 Not necessarily counterfactual

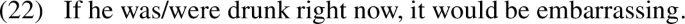

While the marking employed in (1b) is the form one would use in situations where the antecedent is counterfactual, it can also be used in other situations, so it cannot be said to encode counterfactuality. Sentences that have the same morphological make-up as (1b) but differ in lexical aspect, for example the following “Future Less Vivid” (FLV) conditional, do not give rise to a counterfactual inference:

One can’t conclude from (2) that you will not take the 5 pm train and that you will not get there by midnight.

There are other examples of non-counterfactual “counterfactuals”, such as the famous case from Anderson (1951):

Clearly (3) can be uttered by someone who believes that Jones has taken arsenic, thus does not believe that the antecedent is counterfactual.Footnote 2

In addition, the morphosyntax in question has additional uses outside of conditionals that we will discuss in Part II of this article and that do not support a counterfactual semantics for the marking.

So, we shouldn’t call the morphosyntax “counterfactual marking”.

1.2 Not necessarily subjunctive

Neither should we call the morphosyntax “subjunctive marking”, since the subjunctive mood is neither necessary nor sufficient for such conditionals (Iatridou, 2000, 2021).

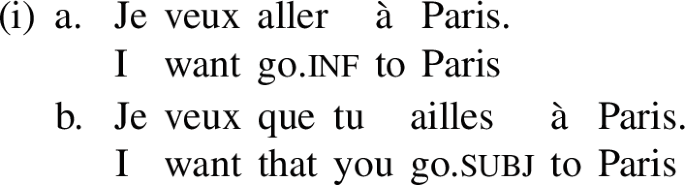

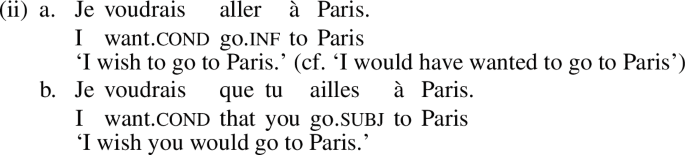

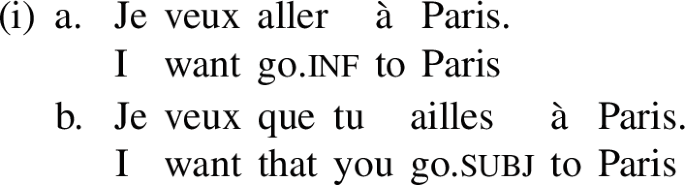

Some languages (Dutch for sure, and arguablyFootnote 3 English) simply do not have a subjunctive mood but can still construct conditionals of this sort. That subjunctive mood is not necessary can be seen even in languages that otherwise do have a subjunctive like French. French has a subjunctive, for example in the complement of the verb “doubt”:Footnote 4

But the subjunctive is not used in sentences like (1b)/(2)/(3):

Instead of the subjunctive, in the antecedent we see a past indicative, and in the consequent, we see the “conditionnel”, a combination of future + past + imperfective(Iatridou, 2000). Iatridou (2000) argued that subjunctive appears in the relevant conditionals only if there is a paradigm for the past subjunctive. French does not have past subjunctive anymore, so the marking in the antecedent consists of past indicative (and imperfective, as we will see). In previous stages of French, where there was still a past subjunctive, this would appear in the marking of the antecedent in counterfactual conditionals. In sum, the subjunctive is not necessary for the expression of counterfactuality.

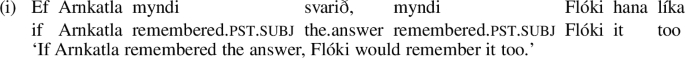

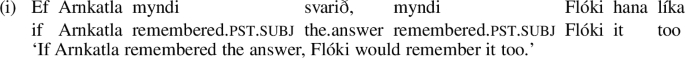

That the subjunctive is not sufficient for the expression of counterfactuality can be seen in Icelandic, where it appears under I-to-C movement necessarily, without any “counterfactual inference” (Iatridou & Embick, 1993; Iatridou, 2021):

Both (7a) and (7b) are non-counterfactual, non-FLV conditionals.Footnote 5 (7a) with the verb in situ has indicative mood, while (7b) with the verb in first position is subjunctive, with no concomitant change of meaning with regards to counterfactuality. (7c,d) show that the mood switch is necessary and entirely conditioned by the position of the verb. In counterfactual conditionals, what appears in Icelandic is the past subjunctive.Footnote 6

So the subjunctive appears in a proper subset of the cases where counterfactual marking involves past tense, namely in those languages that make temporal distinctions in their subjunctive and have a paradigm for past subjunctive.

1.3 X-marking

Since neither the term “counterfactual conditional” nor “subjunctive conditional” will do, we propose that we need new terminology, which will have the advantage of not suggesting (right or wrong) associations. We propose to use the term “O-marked conditional” (where “O” can stand for open, ordinary, or whatever other mnemonic the reader prefers) for (1a). We propose to use the term “X-marked conditional” (where “X” can stand for eXtra, or whatever other mnemonic the reader prefers) for (1b)/(2)/(3).

Languages can use different forms of X-marking in the antecedent and consequent of X-marked conditionals. We see this above in English and in French. Some languages do not have distinct markings: German for example uses its past subjunctive in both clauses. Whenever relevant, we will distinguish between “antecedent X-marking” and “consequent X-marking”.

1.4 The project

We believe that X-marking is a useful heuristic category for linguistic investigation. For each individual language, one would begin with this question: What are the ways in which conditionals about counterfactual scenarios differ from those about epistemically open scenarios? As proposed here, let’s call the distinctive marking used for counterfactual conditionals X-marking.

A number of follow-up questions should then be explored for each specific language:

-

Is X-marking also used in Anderson conditionals (and similar cases) and FLVs? If so, one can probably conclude that it isn’t strictly counterfactual marking.

-

Is there X-marking both in antecedent and consequent? If so, are the exponents distinct?

-

If X-marking is complex, what are the components of X-marking? Do the components have other uses in the language, separately or in combination?

-

Does X-marking have uses outside conditionals? As we will see, there are environments where X-marking appears in several languages: the distinction between wants and wishes, the distinctions between musts and oughts, the distinctions between mays and mights, and a choice between O-marking and X-marking in combination with approximatives like almost.

Once these basically descriptive, empirical questions have been answered, one can proceed to attempting a language-specific analysis of X-marking. What is the meaning that X-marking contributes in conditionals? Can this be specified in a unified way with any other uses of X-marking? If X-marking is complex, what do the individual components contribute to the meaning of X-marking? Is the meaning that a particular component contributes to X-marking the same meaning that it contributes when it occurs elsewhere in the language, on its own or with other components, perhaps distinct from its “partners” in X-marking?

Like with any marking that is correlated with a semantic contribution, we can ask whether X-marking (or any particular part of it) is effective or reflective. By that we mean whether X (or part of X) makes a direct contribution to compositional semantics or whether it merely reflects that something somewhere else in the composition is semantically active. Similar issues arise in the analysis of tense (some tense-marking may simply reflect higher temporal operators, a.k.a. “sequence of tense”), of negation (e.g. in “negative concord”), and in other areas of grammar. In the case of X-marking, the question arises twice: for “consequent” X-marking and “antecedent” X-marking.

There are also some questions about the morphosyntactic make-up of O-marked conditionals. In particular, is there an encoded meaning of O-marking that competes with the meaning of X-marking? Or is O-marking simply what happens when X-marking is absent?

We prefer methodologically to work with a starting hypothesis of total uniformity: all languages have X-marking, in all languages X-marking has the same overall meaning in all its uses (not just in conditionals), in all languages where X-marking is made up from more than one component, those components have the same meaning when they are used elsewhere, on their own and in combination with elements other than those they combine with in X-marking. In the ideal case, the morphosyntactic category of X-marking corresponds to a unique and uniform notional categoryFootnote 7, both internal to a specific language and cross-linguistically; in other words, X-marking has a uniform meaning universally. None of this is likely to be the case, certainly not in full generality, of course, but it is a productive methodology. Only careful language-specific investigations coupled with empirically grounded cross-linguistic comparison and generalization will show whether the initial hypothesis of total uniformity can be maintained. We will propose an informal statement of a candidate uniform meaning for X-marking, but we will leave any attempt at solidifying or refuting the proposal to future work.Footnote 8

The article has two parts. In Part 1, we focus on X-marking in conditionals and closely related cases. We will survey some of the forms X-marking can take and discuss some approaches to the question of the distinctive meaning that X-marking contributes in conditionals. In Part 2, we explore two very common uses of X-marking outside of conditionals and discuss the consequences of these uses for the prospects for a unified meaning of X-marking. Our aims remain modest and we do not provide a worked out formal analysis. We conclude with a to-do list. The overall goal of the article is to lay out an agenda for the continued study of X-marking cross-linguistically.

2 Part I: X-marking in conditionals

3 The form

Languages can be divided into two groups: those that have dedicated X-marking, and those where the exponents for X-marking appear to have other functions as well.

HungarianFootnote 9 is a language with dedicated X-morphology: the morpheme -nA is added to an O-conditional, and -nA does not appear to have any other use in the language. Our pair in (1,a,b) appears as (8)/(9) in Hungarian, where (9) differs from (8) only in the presence of -nA. Moreover, what we see is that in Hungarian, there is no difference between antecedent-X-marking and consequent-X-marking.

Like (1b), (9) is a “present X-marked conditional” (presX): both \(p\) and \(q\) are about the time of utterance.

There are also past X-marked conditionals (pastX), where \(p, q\) are about a time prior to the utterance time. Again, Hungarian is transparent here: the verbs take past tense morphology and on top of that, on a light verbFootnote 10, comes -nA. Compare the presX in (9) with the pastX in (10):

Finally, Future Less Vivids (see Sect. 3.5) also contain the X-morpheme of Hungarian. The difference between a presX and a FLV is a function of the lexical aspect of the predicates involved (Iatridou, 2000) and so we would expect an FLV to look morphologically like a presX in terms of its tense and (viewpoint) aspect morphology, which it does also in Hungarian. Compare the FLV in (11b), with the O-marked future-oriented conditional in (11a). The two differ only in the presence of -nA in (11b):

So for Hungarian, the task ahead would appear to be straightforward: find the difference in meaning between O-marked and X-marked conditionals and attribute that meaning to -nA.Footnote 11

The project becomes much more complicated with languages where the exponents associated with X-marking play different roles in other environments. Such languages variably use past tense, imperfective, future and/or subjunctive to mark the difference between X- and O-marked conditionals.

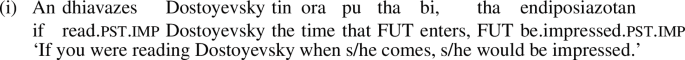

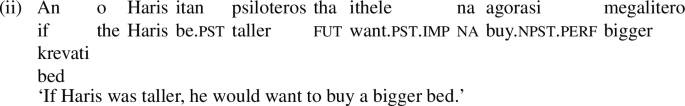

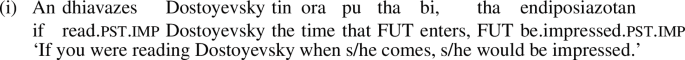

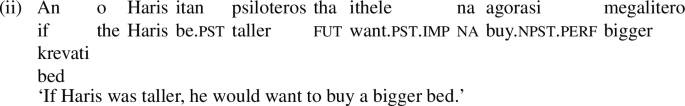

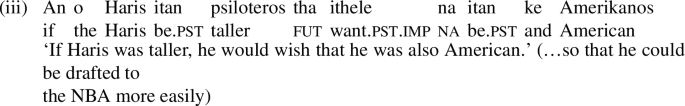

For example, Greek uses past and imperfective in the X-marked antecedent. The hypothetical events described in (12) (from Iatridou, 2000) are not interpreted in the past, as one would expect from the presence of the past tense, nor as being in progress or habitual, as one would expect from the presence of the imperfective. The (complete) burial would happen after the chief has (completely) died, a perfective description, rather than when he is in the process of dying:

Yet, the morphology is past and imperfective and obligatorily so. For this reason, the relevant morphemes are sometimes referred to as “fake” (following Iatridou (2000)), regardless of the analysis of this phenomenon. So, Greek antecedent X-marking consists of fake past and fake imperfective.Footnote 12 Consequent X-marking in Greek consists of fake past, fake imperfective and the future marker (a combination very similar to the Romance “conditional mood” we already mentioned earlier; see again Iatridou (2000) for details).

English, among many others, is also a fake past language. That is, its antecedent X-marking consists of past, as can be seen in (13a,b) where the past morpheme in the antecedent clearly does not yield past event descriptions. To get a pastX, one more level of past is needed for the actual temporal backshifting, as seen in (13c). Among the languages we discuss here, English is in a minority where antecedent X-marking appears to consist only of past tense.

Consequent X-marking in the examples below consists of past tense and the modal wollFootnote 13\(^{,}\)Footnote 14:

The literature identifies many other languages whose X-marking strategy employs morphemes that have apparently different uses in other environments.Footnote 15 As we’ve said, here the challenge is much harder than in Hungarian. It is not sufficient to find the difference in meaning between O- and X-marked conditionals and hardcode it as the meaning of the relevant morpheme(s). What is required is to understand what the meaning of the morpheme(s) is so that the non-X-marking uses are also explained. For example, in Greek, one would have to give a meaning for the past tense and imperfective morphemes so that sometimes they yield the meaning of X-marking, and sometimes they yield past progressive (or past habitual) event descriptions.

Most proposals in the literature that attempt to work towards a compositional analysis of X-marking concentrate on the role of (fake) past tense alone in the role of X-marking, ignoring other elements in X-marking, like imperfective aspect in Greek, Romance etc. This would have made sense if all languages had been like English, where (antecedent-) X-marking consists only of fake past. But as we already said, a great number of languages have additional morphological exponents in their X-marking. As we have seen, Greek (as well as the Romance languages and others) also has fake imperfective.Footnote 16 If X-marking consists of past and imperfective in Greek and just past in English, one would have to come to either one of two conclusions about [past]G(reek) and [past]E(nglish):

-

a.

Since [past]G needs help from the imperfective for X-marking and [past]E does not, the past morphemes in the two languages make different semantic contributions: [past]G \(\ne \) [past]E or

-

b.

The past morphemes in the two languages do make the same contributions [past]G = [past]E and the obligatory imperfective in Greek X-marking makes no semantic contribution but has to be there for language-specific morphological rulesFootnote 17.

Either conclusion has gone mostly under-appreciated by work that focuses only on the role of past in X-marking. But one has to be conscious of the fact that one of these conclusions seems unavoidable if one gives the job of X-marking to the past morpheme alone. One should not assign a meaning to fake past alone without addressing this consequence.

In this article, however, we will not even try to disassemble the meaning of X-marking where it is complex. We will be concerned only with its overall meaning contribution.

4 X-marking in conditionals as domain widening

We start with an intuition about the meaning of X-marking in conditionals, while keeping in mind that the goal will ultimately be to find a unified meaning for all uses of X-marking that are on our agenda (we look at non-conditional uses of X-marking in Part II of the article). The intuition we explore is one that is common to many theories of X-marking.

4.1 Modal domain widening

The core of the insight was developed by Stalnaker within his account of conditionals (Stalnaker, 1968, 1975, recently lucidly re-explicated in Stalnaker, 2014). The strategy he advocates is very much congenial to our modest goals in this article: identify a meaning for X-marking without looking at its morphosyntactic composition or realization.Footnote 18 Stalnaker’s answer to the question of what X-marking means is this: “I take it that the subjunctive mood in English and some other languages is a conventional device for indicating that presuppositions are being suspended” (Stalnaker, 1975: p. 276).

What does this mean? The idea is that O-marked conditionals operate within the confines of the set of worlds defined by what is currently being presupposed in a conversation: the context set. X-marking signals that presuppositions are being suspended: the result is that the conditional can access worlds outside the context set.

Stalnaker himself gave a semantics for if p, q conditionals that is relative to a selection function f that for any evaluation world w and antecedent p selects a particular p-world, which is then claimed to be a q-world. So, his proposal for the meaning of X-marking in conditionals amounts to this:

-

O-marked conditionals: the selection function f is constrained to find a p-world within the context set (the set of worlds compatible with all the presuppositions made in the context of the current conversation).

-

X-marked conditionals: f may reach outside the context set.

-

That is, with X-marking, we abstract away from some established facts and then run a thought experiment. We then conclude that in the selected p-worlds, even those outside the context set, the consequent is true.

Why would we want to or need to reach outside the context set? One reason is that p may be presupposed to be false: there are no p-worlds in the context set. So, in that case, X-marking is necessary. But beyond that, Stalnaker convincingly demonstrates the application of his view of X-marking to two of the recalcitrant cases of X-marked conditionals: Anderson-type cases, which we’ve already mentioned, and modus tollens-type cases. First, take Anderson examples:

Here is Stalnaker’s gloss on this case:

In this case, it is clear that the presupposition that is being suspended in the derived context is the presupposition that she is showing these particular symptoms

the ones she is in fact showing. The point of the claim is to say something like this: were we in a situation in which we did not know her symptoms, and then supposed that she took arsenic, we would be in a position to predict that she would show these symptoms. (Stalnaker, 2014: pp.185)

Next, take what will call a “modus tollens” case:

The reasoning in (15) is meant to be an argument for the falsity of the gardener doing it, so if the X-marking were a signal of counterfactuality, the conclusion of the argument would feel redundant. In other words, this is similar to the Anderson case in showing that X-marking does not encode counterfactuality. But a domain widening story is plausible. Stalnaker’s diagnosis:

In this case, the presupposition that is suspended is the proposition, made explicit in the first premise of the argument, that there are no muddy footprints in the parlor. The idea behind the conditional claim is something like this: suppose we didn’t know that there were muddy footprints in the parlor, and in that context supposed that the gardener did it. That would give us reason to predict muddy footprints, and so to conclude that if we don’t find them, he didn’t do it.

(Stalnaker, 2014: pp.185)

We think this is a successful gloss on the meaning effect of X-marking in conditionals: X-marking signals that the conditional can reach outside the normal domain of quantification. For what follows, we will adopt the Stalnaker diagnosis of what X-marking means and recast it in the terms proposed in von Fintel (1998), which will eventually allow us to think about extending the idea to the other uses of X-marking we’re concerned with. Instead of Stalnaker’s selection function analysis, we will formulate our discussion in terms of restricted modality in the tradition of Kratzer (1981, 1986, 1991, 2012). Under that perspective, an if p, q conditional involves a modal operator that quantifies over the worlds in a certain domain (“modal base”) and that is restricted by the if-clause to just quantifying over the p-worlds in the modal base.

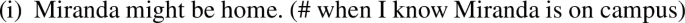

We can now formulate the following idea about the meaning contribution of O/X-marking in the case of conditionals ranging over a modal base of possible worlds:Footnote 19

-

O-marking signals that the modal base is contained in the set of epistemically accessible worlds (or: the “epistemic set”).Footnote 20

-

X-marking signals that the modal base is not entirely contained in the epistemic set.

Obviously, this is rather specific to the case of conditionals. We will soon turn to the question of whether there is any hope of extending the coverage of this diagnosis to the other cases of O/X-marking we are concerned with in this article. But first, we can situate existing theories of X-marking against the basic insight about domain widening that we just explicated.

As we’ve mentioned, existing theories of X-marking are almost exclusively focused on analyzing the contribution of “fake past” in languages that use past tense in (part of) X-marking. So, let’s look at what the past is supposed to do.

4.2 Past-as-past versus past-as-modal

Schulz (2014) coined the terms “past as modal” and “past as past” for the two kinds of proposals for what/how past tense (part or whole of X-marking) contributes to the interpretation of X-marked conditionals.Footnote 21

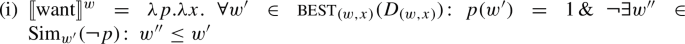

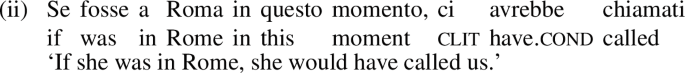

In the past-as-modal view, which includes Iatridou (2000), Schulz (2014), Mackay (2019), and others, the “past” morpheme has an underspecified meaning which yields different meanings depending on whether it is “fed” times or worlds. Abstracting away from the specific proposals, one can represent this view as in Fig. 1, with \(\mu \) being the morpheme in question.

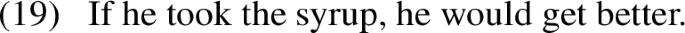

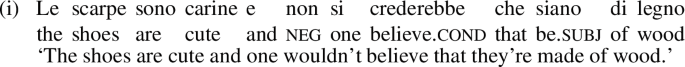

In the past-as-past view, advocated among others by Ippolito (2003, 2013), Arregui (2005, 2007), Romero (2014), Khoo (2015, 2022), X-marking (that is, the past morpheme in it) is a past operator with wide scope over the conditional, which results in the (mostly metaphysical modal’s) modal base being calculated in the past time of the utterance time. Roughly: the past takes us back to a time where the (non-past) conditional could still have been true. The picture in Fig. 2 illustrates this move to a past splitting point.

In other words, for these accounts, the “fake” past that we see in X-marked conditionals is an actual occurrence of an honest-to-goodness past morpheme with scope above the conditional (or the modal operator that underlies the conditional, under a Kratzerian perspective).

4.3 The two views of X-past and domain widening

How do these two views relate to the Stalnakerian domain-widening idea?Footnote 22

The “past-as-past” analysis delivers domain widening through the fact that certain modal accessibility relations or modal bases narrow as time progresses: more and more metaphysically possible futures become impossible as facts in the world develop. And in the epistemic dimension: the more we learn or the more evidence becomes available, the fewer worlds are epistemically possible. Therefore, treating the past component of X-marking as moving the time of the modal operator that underlies the conditional construction into the past of the evaluation time will result in a domain that is wider than it would have been at the evaluation time. We note that there are at least two kinds of cases of X-marked conditionals that may fall under domain widening but that are harder to analyze as being due to a past time of evaluation:

It’s not entirely clear that someone who endorses (16a) is thereby committed to the claim that there was a time in the past (before the big bang?) at which it was open whether there would be a big bang.Footnote 23 And FLVs such as (16b) do not clearly involve widening via a past evaluation time either: given that FLVs talk about still open possibilities, going back in time would not seem to serve a clear purpose (for more on the puzzle of FLVs, see Sect. 3.5).

What about the “past-as-modal” views? Here, there is a split. Iatridou (2000) proposed an “exclusion” semantics for X. In her account, X marks that the domain of quantification of the conditional is not wider but fully disjoint from what we have called the epistemic set. It is crucial to remember that this proposal had been made with the main aim of finding a common formulation for the ‘past tense’ morpheme, so that sometimes it is interpreted as a temporal past and sometimes it has the meaning associated with what we now call ’X-marking’. But as a result of trying to bring the past tense interpretation of the relevant morpheme into the fold, Iatridou’s account, and also the one developed more formally in Schulz (2014), do not in fact conform to the domain widening idea. One immediate effect of this is that while the domain of an O-marked conditional, the epistemic set, will contain the evaluation world, the domain of an X-marked conditional will not (since it’s disjoint from the epistemic set). This aspect of these proposals has been shown to be problematic by Mackay (2015) (see also Leahy, 2018). More generally, the prediction is that X-marked conditionals will not obey the principle of Weak Centering,Footnote 24 which is standardly taken to be valid for both O- and X-marked conditionals in the logical and philosophical literature. Another way to see that the exclusion account for X-marking is incorrect is that it wrongly predicts that we should be able to use X-marked conditionals when the truth of the antecedent is common ground but we would like to talk about nearby non-actual antecedent worlds. But the following passage is incoherent:

Under the exclusion account, this should be able to express the coherent thought that while in actuality the butler did it with the ice-pick, in the nearest non-actual worlds, he used a dagger. We therefore will from now on assume that the “exclusion” semantics for X is incorrect.

The other strand of “past-as-modal” views, represented for example by von Fintel (1998) and much more recently (Mackay, 2019), does conform to the domain widening view quite directly. von Fintel (1998) is basically just a reformulation and exploration of Stalnaker’s proposal, while Mackay (2013) attempts to explain the use of past tense in X-marking within this general viewpoint. We find this line of thinking very promising, but there is much that remains to be worked out.

We end this part with a collection of open issues in the study of X-marking in conditionals. And after that, in the second part of the article, we turn to other uses of X-marking.

4.4 Open issues in X-marking on conditionals

While we think that the domain widening diagnosis for what X-marking does in conditionals is promising (and it seems that the field largely agrees), there are many open issues.

Compositional morpho-semantics How do languages compose the overall meaning for X-marking from the component morphology in such a way that domain widening is signaled? This is especially urgent for languages where the morphology involves several distinct components.

The interaction of antecedent and consequent X-marking How do antecedent X-marking and consequent X-marking collaborate in this process? Is either of them a reflection, some kind of agreement, with what the other effects? Or are both reflections of some other operation? Or are both separately active or effective?

Locality of the meaning contribution We have formulated the basic idea of X-marking in conditionals as involving a signal about the domain of quantification, rather than, say, a more “local” property of the antecedent and consequent propositions. Alternatively, it may be feasible to “project” the signal from the component propositions. This is an idea hinted at in Iatridou (2000) and pursued to some extent by Leahy (2018) and somewhat differently by Crowley (2022).

The derivation of the counterfactual inference Domain widening is meant to cover non-counterfactual uses of X-marked conditionals (Anderson, modus tollens, FLVs). But an out-of-the-blue X-marked conditional typically is interpreted as signaling counterfactuality. Most authors say this is an implicature.Footnote 25 But how precisely is this implicature derived? A prominent proposal is that it is an “anti-presupposition”: O-marking presupposes that the domain is within the epistemic set, and using X-marking is interpreted as a signal that the presupposition of O-marking is not something the utterer wants to commit to. Exactly how this works differs between different proposals, see again Leahy (2018) and Crowley (2022) for discussion.Footnote 26

The final open issue we would like to draw attention to deserves its own subsection.

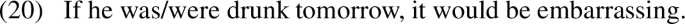

4.5 The puzzle of future less vivids

Iatridou (2000) re-introduced the term “Future Less Vivid” from grammars of Ancient Greek. The term FLV was meant as a descriptive term indicating that the future it described is less likely to come about than its polar opposite. Indeed, it looks like (18a) may be better than (18b):

Iatridou argued that an FLV comes about morphologically in two ways:

-

1.

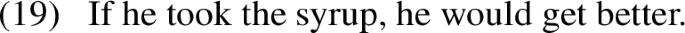

One way is by X-marking on a non-progressive telic predicate in the antecedent, as in (19):

(19) is necessarily interpreted as an FLV.

-

2.

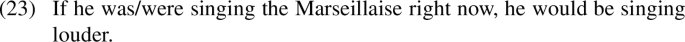

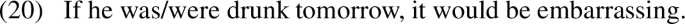

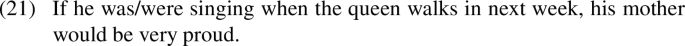

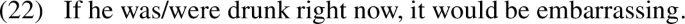

The second way of deriving an FLV is by X-marking on a stative or progressive predicate:

But unlike with X-marking on telic predicates, where the FLV interpretation is necessary, X-marking on a stative or progressive can also yield a presXFootnote 27:

Iatridou argued that the above is the expected result from the following perspective. An O-marked conditional is evaluated at utterance time or in the future, depending on whether the antecedent contains a stative predicate, a progressive predicate or a telic predicate, as summarized in Table 1.

A non-progressive telic predicate in the antecedent has a future evaluation time necessarily:

A stative or progressive can take either a future evaluation time or be evaluated at UT:

The corresponding X-marked conditionals retain the evaluation time and become FLVs or presXs accordingly, as summarized in Table 2.

In other words, X-marking does not affect the time of evaluation of the corresponding O-marked conditional. If we understand why Table 1 works the way it does, we will also understand Table 2. In other words, which combinations of predicates and viewpoint aspect yield an FLV is indeed a question but it is in all likelihood the same question as the one represented in Table 1. We will not pursue this issue further here but will continue with the questions that FLVs raise for the current discussion.

As said earlier, there is a general belief that FLVs are about unlikely futures. The question is how this ‘unlikelihood’ can be captured within a unified theory of X-marking. Why would X-marking on a future-oriented antecedent yield unlikelihood?

But the challenges do not end there. There are cases where what looks like an FLV, does not come with unlikelihood. Here is an example:

Neither of the two conditionals in (29) conveys unlikelihood about either of the two trains. What does X-marking then do in these cases?

5 An expected reading

To appreciate what makes the constructions we will focus on in Part II of this article so challenging, it is useful to first consider what we expect when X-marking is combined with a modal or attitude predicate:

We have underlined the “consequent” X-marking in the two examples in (30) and italicized the modal/attitude in its scope. Notice that the intuitive meaning is one where the italicized operator is interpreted with respect to a shifted evaluation world. In other words, we hear an implicit conditional: (30a) talks about worlds where an overseas customer decides to buy the coat, and (30b) talks about worlds where Ali is here.

These cases are simply the result of what we expect, given that implicit conditional readings are often available. The presence of an if-clause is not required for conditional would. For one thing, other kinds of constituents can provide an antecedent scenario:Footnote 28

The relevant antecedent scenario can also be introduced in prior discourse (a phenomenon called “modal subordination”, see Roberts, 1989, 2021):

And there are cases where somehow the antecedent scenario has to be reconstructed from subtle clues (see Kasper, 1992 and also Schueler, 2008):

Our perspective on such cases is simply that X-marking continues to do the same job as it does in explicit if-conditionals: it marks that the modal base (of the underlying modal woll) contains worlds outside the epistemic set. And since to evaluate the modal claim, one needs to know what the modal base is, use of X-marking makes clear that some departure from what is epistemically given needs to be contextually salient. This is correct. Consider for example an out of the blue use of the following if-less would (from Roberts and also discussed in von Fintel, 1994):

It will be hard to make sense of an utterance of (34) if no antecedent can be reconstructed.

This article is not the time to delve into if-less would cases like these. But it is important to realize that the phenomenon is wide-spread.

So, the cases of X-marked modals/attitudes that we saw in (30) are entirely expected. From the Kratzerian perspective that we follow, the most plausible formal analysis of such cases is one where there are two layers of modality: the higher layer (would) is where the X-marking is located and it signals that we’re talking about worlds that are at least potentially outside the epistemic set, the lower layer is provided by the modal/attitude embedded underneath would (have to or want to in (30)) and it is evaluated in the worlds that the higher would took us to.Footnote 29

We find such interpretations of X-marking on modals and attitudes across all the languages we have explored. What we turn to now are crucially distinct readings of such structures in some languages, a phenomenon that will need to be accounted for by successful theories of X-marking.

6 Part II: Other uses of X-marking

Existing accounts of X-marking (albeit not under that name) are all about X-marking in conditionals. From a very high level perspective, they all share the diagnosis that X-marking concerns the domain of quantification of the conditional. What we will now add to the mix are uses of X-marking outside of conditionals and the challenges they raise for the semantic analysis of X-marking and the prospects of a unified account.

7 Non-conditional uses of X-marking

We will focus on just two non-conditional environments where X-marking appears: “X-marked desires”, where X-marking appears in a desire construction, and “X-marked necessity”, where X-marking appears on a necessity modal. (Some other uses of X-marking are briefly mentioned in Sect. 5.4.)

7.1 X-marked desires

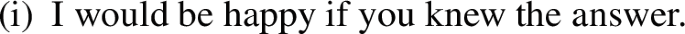

Consider the English expressions of wishes in (35):

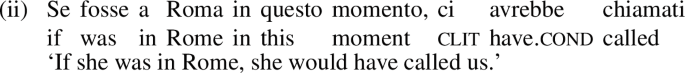

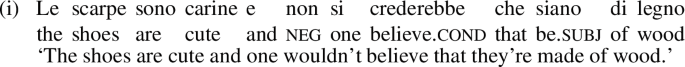

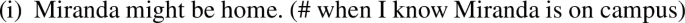

We observe that the complement of wish has the same X-marking morphology that we find in the antecedent of X-marked conditionals. We also observe parallels in the interpretation: (35a,b) convey the counterfactuality of the prejacent proposition (pastX: I did not buy a different car; presX: Aline is not here now), while (35c) has the FLV-type property of leaving it open whether my book will sell well.Footnote 31 One might use the term “‘counterfactual wish” but we worry that this would be potentially misleading in two ways: (i) the desires reported in (35) are desires in the actual world, and crucially not desires in a some other, counterfactual, world, and (ii) in its FLV-incarnation (i.e. with a future-oriented predicate) the complement is not necessarily counterfactual nor even unattainable.

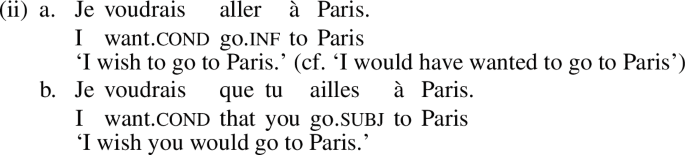

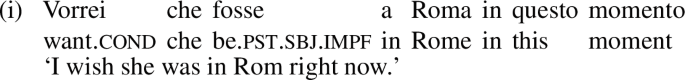

In many languages, there isn’t a lexical distinction between wants and wishes as in English. Instead, there is a morphological commonality between X-marked conditionals and the expression of wishes (Iatridou, 2000): wishes use the same lexical item as wants but the distinction is effected via X-marking. In the full version of the pattern, “consequent X-marking” morphology appears on the embedding verb want, and “antecedent X-marking” morphology appears on the complement of want.

Schematically, what we call the “Conditional/Desire” (C/D) pattern looks as follows:

We will use the term “transparent wish” when the meaning of wish (i.e. actual world desire for an unattainable complement, or an FLV-type case like (35c)) is expressed by X-marking on a desire predicate. The idea of the terminology (which is parallel to the term “transparent ought” coined in von Fintel & Iatridou, 2008) is that what English expresses in the lexicalized form wish is instead expressed, “more transparently”, in combinatory morphology.

As we have said, there are languages without a morphological difference between antecedent and consequent X-marking. We saw that Hungarian is such a language, and that moreover, it has a dedicated X-marker. The way the C/D pattern manifests is that the X-marker -nA appears both on the desire verb and on its complement. Recall Hungarian X-marked conditionals:

To talk about desires and wishes, here is the verb that means ‘like’Footnote 32:

X-marking on the ‘like’-verb and its complement yields the effect we’re concerned with, the want turns into a wish:Footnote 33

In other languages, like Greek and Spanish, antecedent X-marking differs from consequent X-marking and there the C/D pattern shows up more clearly. In Spanish, antecedent X-marking consists of past subjunctive and consequent X-marking consists of “conditional” mood. The way the C/D pattern then manifests is that conditional mood will appear on want and past subjunctive on the complement of want. Here is a Spanish X-marked conditional:

And here is a Spanish X-marked desire:

Spanish, Greek, Hungarian, and others are “transparent wish” languages. English has a lexicalized item wish and manifests only one part of the C/D pattern, namely “antecedent” X-marking on the complement of the desire verb.Footnote 34 This can be seen in the pair in (43), where there is “fake” past in the antecedent in (43a) and the complement in (43b):

If English had been a transparent wish language,Footnote 35 it would have had would on want, as would is consequent X-marking, as in (44a). That is, if English were a transparent wish language, (44b) would have meant (44c), which it does not:

Even though English wish is not an example of a transparent wish, sentences with this item do show one part of the C/D pattern, as we saw, namely the same morphology (fake past) appears on the conditional antecedent and on the complement of the desire predicate.

TurkishFootnote 36 is another language like English, which has a specialized morpheme for unattainable wishes. And like English, it displays the C/D pattern only in the complement of the desire expression. So first let us look at X-marking in Turkish conditionals. Turkish is a fake past language, as can be seen by the use of the “fake” past morpheme in both antecedent and consequent of the FLV in (45). More specifically, consequent X-marking consists of aorist+past.

Antecedent X-marking consists of what is called by grammars the “conditional” affix -sA, followed by the past morpheme, namely sa +pastFootnote 37:

Turkish has the undeclinable (non-verbal) particle keşkeFootnote 38 to convey wish:

In (46) the speaker believes that her wish will not come true. What we also see in (46) is that the complement of the desire-embedder carries antecedent X-marking, namely sa +past. The past morpheme is obviously “fake” since we are talking about (im)possible events in the future. Moreover, the order of morphemes is the tell-tale one of X-marked antecedents: sa +past (see Footnote 37). So Turkish is a language which, like English, displays the complement part of the C/D pattern but not the want part (i.e. it does not have transparent wish).

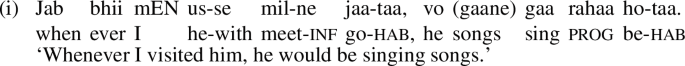

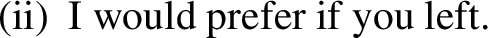

HindiFootnote 39 has a similar particle to Turkish, but we will look into this language because even though Hindi’s kaash may be related to Turkish keşke, its X-marking is different. Hindi taa is described as a habituality marker. However, it cannot appear on a predicate that is by its nature individual-level (as reported by Iatridou (2000), based on p.c. from Rajesh Bhatt). It can only appear on “derived” generics:

But taa does appear on individual-level predicates in X-marking:

That is, “fake” habitual is part of Hindi X-marking in both antecedent and consequent.Footnote 40 The same conclusion is supported by the following argument. The habitual marker cannot co-occur with the progressive:Footnote 41

But in an X-marked conditional, hab and prog co-occur:

Since the habitual marker is part of Hindi (antecedent) X-marking, by the C/D pattern, we expect it in the complement of kaash. This prediction is verified. hab appears on an individual-level complement of kaash:

And it appears also on a progressive event description in the complement of kaash:

Finally, the following instantiation of the C/D pattern is too cute to omit. Since Hindi X-marking contains a fake hab, one expects (and gets) two occurrences of hab in an X-marked conditional when there is an actual generic predicate in the antecedent:

This correctly predicts that we should also get two hab markers when the complement of kaash is a generic predicate:

So the C/D pattern is real, even if there are languages, like English, Turkish and Hindi,Footnote 42 which manifest only one part of this pattern.Footnote 43

In sum, in this subsection we have seen that there is an environment where X-marking appears outside conditionals and that this has an interpretation other than the otherwise expected shifted evaluation world reading: X-marked desires are used to express wishes in the actual world.

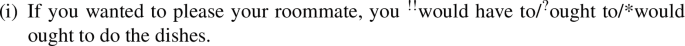

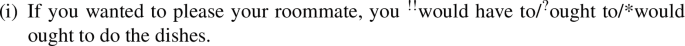

7.2 X-marked necessity

The second environment where we see X-marking outside of conditionals without a shifting of the evaluation world is necessity modals. As discussed in detail in von Fintel and Iatridou (2008), necessity modals often come in strong versus weak variants/pairs. In English, for example, we can distinguish weak necessity modals ought, should and strong necessity modals must, have to. One way to show that weak necessity modals are not strong is that they can occur without contradiction with the negation of a strong necessity modal:

It is important to note that the strong/weak necessity distinction holds across modal flavors: it arises not just with deontic modality as in (56), but also with epistemic modality and goal-oriented modality:

English has lexicalized weak necessity modals like ought but many other languages do not (von Fintel & Iatridou, 2008). In those languages, the modal that shows the pattern in (56) is an X-marked necessity modal.

In Hungarian, its X-marker -nA appears on the modal and without it the sentence is a contradiction. That is, the following pattern is exactly like (56):

Hungarian is a language in which antecedent X-marking and consequent X-marking are the same. So we do not know which of the two appears on the modal. However, once we look at other languages, we see that it is consequent X-marking, not antecedent X-marking, that appears on the necessity modal to yield weak necessity. Consider Spanish:

With consequent X-marking on the modal, the sentence passes the ought-test:

So Spanish, as well as Greek and others (see von Fintel & Iatridou, 2008) are “transparent ought” languages.

If English had been a transparent ought language, it would have had would on have to, and (62b) would have meant (62c), which it does not:

So the way there is a Conditional/Desire pattern, morphologically speaking, there is also a Conditional/Ought pattern, again morphologically speaking. We saw that the C/D pattern has two parts, one regarding transparent wish, and one regarding the complement of the desire verb. One may therefore ask whether there is a complement part to the C/O pattern as well. For many languages this cannot be tested because modals take infinitival complements. However, Greek is a language whose modals can take complements that are inflected and so there is an embedded verb that can in principle carry antecedent X-marking morphology. In (i), the translation corresponding to the ought-test in (56a), there is no X-marking on the complement, and this makes intuitive sense: the complement is not a contra-to-fact situation, unlike in most cases of transparent wishes.

It is possible to put X-marking on the complement of an X-marked necessity modal, as in (ii), but then the sentence translates as you ought to have done the dishes, where indeed the complement is contra-to-fact.Footnote 44

7.3 A principled ambiguity: endo-X versus exo-X

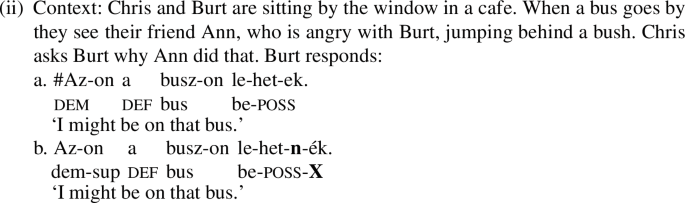

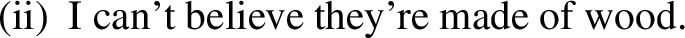

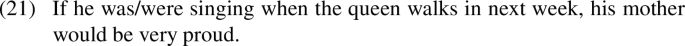

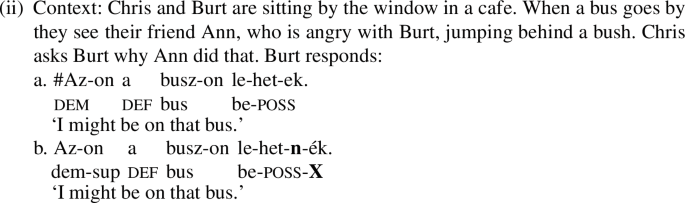

We saw in Sect. 4 that when one puts X-marking on modals and attitudes, it is entirely expected that we would get interpretations where the evaluation world is shifted away from the actual world, to some salient, possibly counterfactual scenario. This entirely expected reading is available for X-marked desires and X-marked necessity in all the languages we have looked at (as we will soon show). The remarkable fact is that there is another reading that does not involve a shift in the evaluation world: X-marked desire claims can be about actual world desires and X-marked necessities can be about actual world necessities. We will now discuss this principled ambiguity in these constructions in transparent languages.

Let us start with X-marked necessity. Sentences that contain this are ambiguous between a weak necessity modality in the actual world (like English ought) and a strong necessity modal in a counterfactual world (English would have to). In transparent ought languages, these are the same form. Consider Greek for example, where consequent X-marking is a combination of future and past and imperfective. On the strong necessity modal, this can yield the meaning of weak necessity ought:

But it can also yield the meaning of a strong necessity modal in a “counterfactual” scenario:

Note that the weak necessity claim in (65) signals there is more than one way to get to the island but the boat is by some measure deemed preferable by the speaker. In the strong necessity claim in (66), however, the boat is the only way to get to the island.Footnote 45

We propose to call the two interpretations of X-marking on necessity modals endo-X and exo-X:

- endo-X:

-

the modal is making a claim about the actual world

- exo-X:

-

the modal is making a claim about other worlds in which some hypothetical/counterfactual scenario holds

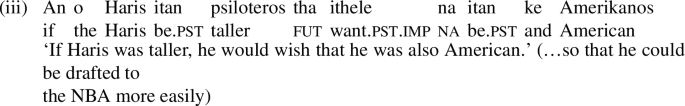

X-marked desires in transparent languages are equally ambiguous, and in the same two directions. Sentences that contain an X-marked desire are ambiguous between a desire in the actual world (like English wish) and a desire in a counterfactual scenario (English would want to). In transparent wish languages, these are the same form. Consider X-marking on the Greek verb thelo (‘want’). It can yield a desire in the actual world towards something unattainable:

Or a desire in a counterfactual scenario:

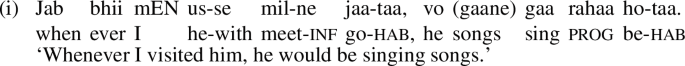

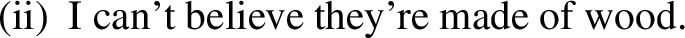

The crosslinguistic picture is summarized in Fig. 3,Footnote 46 modified from von Fintel and Iatridou (2008). With our current terminology, we would call the interpretations on the left side of the diagram endo-X and the ones on the right side exo-X.

Recall that in Sect. 4, we suggested that there is an expected two-layered meaning of X-marked modals/attitudes. This is what we now call exo-X and it is what is found on the right side of the diagram in Fig. 3. The nature of endo-X in contrast is plausibly that there is just one layer of modality and that X-marking carries a signal about the modal parameters (modal base, ordering source) of the modal/attitude it is attached to.

We note one striking difference between X-marked desires and X-marked necessity. For the latter, X-marking comes with a weakening of the modal claim, but there is no sense of weakening in the case of unattainable desires. A successful theory of X-marking should explain this difference.

We have now seen that X-marking appears not just on conditionals but also in desire constructions and with necessity modals. A theory of X-marking should have the ambition of covering all these uses in a unified analysis. The first step towards that is to find a common denominator for the meaning contribution of X-marking in all these cases. The second step would be to find an analysis that explains how in each language the morpho-syntactic components of X-marking (such as fake tense, fake aspect, subjunctive, etc.) contribute to its meaning. For this article, we leave the second step aside, as already mentioned, and discuss the prospects for a unified meaning for X-marking as an atom.

Before we turn to what a unified meaning for X-marking might be, we would like to discuss two issues: (i) is our focus on desires and necessity modals too narrow? (ii) could what we have called endo-X be reduced to exo-X and thus be solved more easily?

7.4 Are there more uses of X-marking?

The two non-conditional, endo-X uses of X-marking that we have discussed are with desire predicates and necessity modals, and we will focus on those in the remainder. But we should mention that this can’t be the whole story:

-

X-marking with an endo-X interpretation can also appear on possibility modals, where one tempting intuition is that it contributes a meaning of “remote possibility” (somewhat akin to the unlikelihood meaning often attributed to FLVs, but as we saw in Sect. 3.5, that is not entirely unproblematic).Footnote 47

-

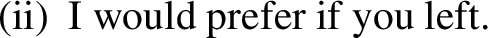

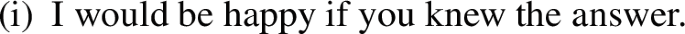

One often finds X-marked modals and attitudes described as adding a layer of politeness on top of the meaning that the O-marked version would have conveyed. So, a sentence like I would prefer red wine states an actual preference but one that is somehow expressed more politely. We do not know what to make of this widespread phenomenon, let alone how to integrate it into the overall analysis of X-marking.Footnote 48

-

In some languages, sentences with approximatives like almost come in both O- and X-variants, with subtle differences that remain unexplored.Footnote 49

-

In German, as described and analyzed by Csipak (2020), X-marking on a simple non-conditional sentence can be interpreted as committing to the actual truth of the prejacent and offering it as a possible solution to a salient decision problem.

We wouldn’t be surprised if there is even more.Footnote 50

There is also the converse question in a way: there are environments where all the necessary grammatical ingredients are present, but no endo-X reading comes about. We already saw two such cases in English, collected here for convenience:

As we already know at this point, English consequent X-marking is would + VP, as seen in (69a)/(70a). And of course, (69b) and (70b) only have the exo-X reading. In transparent languages, the consequent morphology that would have appeared in (69a)/(70a) would have yielded the endo-X reading when placed on the matrix verb, in (69b)/(70b) (in addition, of course, to the exo-X reading). That is, in transparent languages, (69b) would be about a desire in the actual world and (70b) about (weak) necessity in the actual world.

But in English, (69b)/(70b) only have the exo-X reading. That is, (69b) is not equivalent to (69c), nor (70b) to (70c). As we saw in Fig. 3, English has special lexical items for someFootnote 51 of its endo-X readings. Does this explain the non-equivalence of (69b,c) and (70b,c)? That is, is there a blocking effect going on for the composition of (69b)/(70b) into an endo-X reading? That might be one possible explanation for the fact that (69b)/(70b) lack the endo-readings. However, we think that it is too early to conclude this, so we are placing also this question on the to-do list.

Finally, it is instructive to discuss a case raised by a reviewer, who was suggesting that relevant uses of X-marking as well as the C/D pattern, also occur with doxastic attitudes. Their example was the following, naturally occurring Italian sentence:

The context for the example turns out to be a document with guidelines for how to train a new puppy. The new owner is being told not to reprimand the puppy for doing “its business” in the house, because if the owner did that, the puppy would misunderstand the signal and would think that it had done something wrong by doing its business in plain sight of the owner (and would thus hesitate to do its business even on an outdoor walk and rather prefer to do it when alone, no matter where it is). In other words, the example is about a hypothetical belief the puppy would have if the owner reprimanded it. This is thus clearly a case of what we call “exo-X”: the X-marking on the attitude verb signals that the attitude is evaluated in a hypothetical environment. We therefore disagree with the reviewer that this shows that X-marking on epistemics is parallel to what happens with bouletics. There is no “endo-X” interpretation of (71), which might talk about an actual belief with a counterfactual complement. In fact, such an interpretation is inconceivable.Footnote 52

In fact, we have not come across any endo-X doxastics. This raises the question of why the relevant uses of X-marking apparently only occur with metaphysical, epistemic, bouletics, teleological, and deontic modality. We do not know and thus we leave this as an open puzzle: Why can endo-X-marking not occur on doxastic modals/attitudes?Footnote 53

7.5 No easy way to reduce endo-X to exo-X

Let us quickly dispense with one attempt at reducing all three of our uses of X-marking (conditional, wishes, weak necessity) to a common denominator. In von Fintel and Iatridou (2008), the proposal was floated that X-marked necessity involves a meta-linguistic counterfactual conditional operating on the necessity modal: “if we were in a context in which the secondary ordering source was promoted, then it would be a strong necessity that ...”. Whatever one might think of the prospects of this idea, it’s instructive to try to extend it to X-marked desires. Could the X-marking there be a reflection of an implicit counterfactual analysis?

The idea might be that “wish that p” means something like “if p were attainable, would want that p”. To put this kind of proposal to the test, let’s imagine Laura is the sort of person who only wants things that are attainable. If something is unattainable, that suffices for her to not want it. I happen to know her general tastes in men and know with certainty that Pierce Brosnan falls within that category. As things stand, a date with him is unattainable, hence Laura has no desires about it. Now consider:

If the implicit counterfactual conditional analysis we are evaluating for sentences like (72) were adequate, we would expect the sentence to be judged as true in our scenario. After all, if a date with Pierce Brosnan were attainable, Laura would want to go out with him. But (72) is judged as false, which means that the sentence conveys the existence of a desire in the actual world. And since Laura doesn’t have the desire to go out with him, because a date is unattainable, the sentence is false. So, a quick reduction of X-marked desires (and let’s face it, X-marked necessity) to some kind of meta-linguistic implicit counterfactual is not feasible.

7.6 Interim summary

We can summarize the cases we have seen as follows:

And we have proposed that the exo-X readings are all essentially X-marked conditionals, whether with or without an explicit antecedent. This means that our question becomes what X-marking does in the following three cases:

It’s time to see what the prospects are for a theory of X-marking that at least unifies these three cases: conditionals, desire attitudes, and necessity modals.

8 Extending the account

In this final section, we continue to leave aside the question of what the morphological composition of X is and why. Instead, we pretend X is a non-decomposable whole and ask the following question: what would have to be true of the meaning contribution of X so that for conditionals it marks Stalnakerian domain widening, at the same time as it marks a desire as a wish and a necessity as weak. We tackle the two cases of desires and necessity modals in that order. Along the way, we will see that the “past-as-past” kind of approach faces obvious issues with extending to these cases.

8.1 X-marked desires

Our Stalnaker-inspired picture of the meaning of X-marking in conditionals is that X marks the widening of the domain of quantification of the conditionals: worlds outside the default set (context set or epistemic set) are included in the domain. Can this picture be extended to the case of X-marking in desire ascriptions?

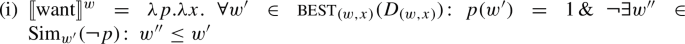

The simplest, minimally viable analysis of the semantics of want is something like this:Footnote 54

This says that an agent x wants p in world w iff all of the worlds in the relevant domain D that are “best” as far as x in w is concerned are p-worlds.

What is the domain D? And does it make sense to think of X-marking in the case of desires as marking a widening of the domain, just as it does by assumption in the case of conditionals?

The consensus in the literature is that the domain of desire ascriptions is related to or identical to the set of doxastically accessible worlds for the agent of the desire, the agent’s belief set or doxastic set. The original argument for this (developed in Heim, 1992, following Karttunen, 1974) comes from presupposition projection, where it can be shown that presuppositions triggered in the complement of the desire ascription are projected to the belief set of the agent, rather than the context set or the speaker’s epistemic set:

So, we might say that the default value for D in (74) is the set of worlds compatible with x’s beliefs in w.Footnote 55

What would this mean for the analysis of X-marked desires? One option we can quickly dismiss is that just like in the case of conditionals where X marks that the domain is not entirely included in the epistemic set of the conversation, X on desire would mark that the domain (here: the agent’s doxastic set) is not entirely included in the epistemic set of the conversation. This is not promising: an agent is likely to have some beliefs that are false (and hence not in any epistemic set) or disagree with the conversational context’s assumptions. But then X should be virtually obligatory on desire ascriptions, which is not the case.

Much more promising is the idea that X-marked desires signal that the domain of the X-marked desire ascription is not entirely included in, that is, is wider than the default domain, that is, the agent’s doxastic set. In other words, X would mark that worlds outside the agent’s doxastic set are included in the quantified claim made by the desire ascription.

When the agent has a desire for a proposition p that they think is unattainable, the default D (their doxastic set) does not contain any p-worlds and therefore, the semantics in (74), with the default value for D, would predict that the desire ascription x wants p is straightforwardly false (or, worse, a presupposition failure, if we build in a presupposition that D contains p-worlds).

To construct an ascription of an unattainable desire, D then has to be wider than the agent’s doxastic set. It needs to include some p-worlds.Footnote 56 Once these worlds have been added to D, the semantics in (74) can proceed and claim that in this widened set, the best worlds are in fact all p-worlds. The idea then would be that X-marking is a signal that such a widening from the default doxastic set is active.

Iatridou (2000) gave the following examples to show that X-marked desires indeed are associated with a signal about the agent’s (and not the speaker’s) belief set not containing p-worlds:

So, the idea we’re pursuing is that X-marking on desires signals that the domain of quantification is wider than the agent’s doxastic set, which is the default domain for desire ascriptions. But, while we find this picture very attractive, there are difficulties.

The first set of problematic cases are ones where the doxastic set consists entirely of worlds where the complement proposition is true, in other words: the agent believes that the complement is true. There are two observations to be made here:

-

(i)

Our semantics so far would predict that if the agent believes p, the agent thereby wants p, because all of the best worlds in their doxastic set will be p-worlds simply because all worlds in their doxastic set are p-worlds. This is wrong, as pointed out by Stalnaker (1984: p. 89): “Suppose I am sick. I want to get well. But getting well entails having been sick, and I do not want to have been sick.”

-

(ii)

The flip side of this is that sometimes we do in fact want what we believe to be true, as shown by Iatridou (2000)’s example:Footnote 57

The utterer of (77) is making a contingent claim, not one that is trivially true.

Both of these observations show that O-marked wants must be able to look beyond the agent’s doxastic set in order to take into account at least some non-p-worlds when the agent believes that p is true. The question is why there is no X-marking in these cases, in fact, why X-marking is not possible here. In other words, there is an asymmetry: widening to include worlds where an unattainable desire is satisfied can give rise to X-marking, while bringing worlds into the equation where a not desired alternative proposition is true (in the case of (77): worlds where you don’t live in Bolivia) does not go with X-marking.

To maintain our basic idea that X-marking marks domain widening beyond the default, we need to add something to the story of how desire ascriptions work. One possibility is that in these cases, the domain is in fact still the doxastic set but that non-p-worlds outside the domain can be “looked at” without being added to the domain. Then, the domain doesn’t need to be widened and we don’t expect X-marking in these cases.Footnote 58 A perhaps better option is to say that the default domain always contains the closest non-p-worlds even if they are outside the doxastic set. So, the default domain is \(\textsc {dox}^{+\text {not}-p}\). If the doxastic set already includes non-p-worlds, the default domain will be identical to the doxastic set. Otherwise, the default domain will be larger than the doxastic set. Since this would be built into the semantics, it is not domain widening, and thus X-marking is out of place, as we would want.

Under both of these proposals, expressing unattainable desires would still involve actual domain widening: if the doxastic set contains only non-p-worlds (the desire is believed to be unattainable), the domain will have to be widened to include p-worlds. And that is what X-marking signals. So far so good, if a bit intricate. But ...

The second problem for the idea that X-marking on desire predicates marks a widening of the domain beyond the default is that there are O-marked desire ascriptions with unattainable complements:

The example in (78) is from Heim (1992). Given that it is known that no weekend can last forever, and given our idea about X-marking, we would expect that (78) would lose out to the wish-variant:

More precisely, if the difference between O and X-marking is a signal about whether the domain is widened beyond the default value of the doxastic set of the agent, why don’t standard “Maximize Presupposition” considerations outlaw the use of the O-marked form?

Moreover, we find that both forms are acceptable even in transparent desire languages, like Greek:Footnote 59

So, we could say that O-marking does not by itself ensure that the domain has not been widened, but X-marking is only possible with a widened domain. For some reason, the expected competition that would result in an inference from O-marking to a non-widened domain can be obviated.

Finally, we would like to consider an idea that may be traceable to a remark in Heim (1992) about the forever weekend case, which she suggests “might be seen as reporting the attitudes of a mildly split personality. The reasonable part of me knows and is resigned to the fact that time passes, but the primitive creature of passion has lost sight of it.” What if a speaker who utters (78) rather than (79) is signaling that (at least temporarily) they are acting as if a forever weekend is actually attainable, perhaps willfully setting aside the harsh reality? In that case, the example is no longer a counter-example to a theory of O/X-marking that predicts that O-marking signals (via competition with X) that the default domain contains p-worlds. It’s just that the speaker is acting as if their doxastic set is bigger than their rational part would allow. This may prove the right idea in the end. It seems to us that discourse like (78) is not as felicitous in contexts where passionate desires are out of place but precision is required instead, such as in a court of law. But we leave this for another occasion.

We will leave things in this unresolved state and simply state that we hope that the “X marks widening beyond the default domain” idea will turn out to have legs.

Before we turn to our third case of X-marking, we need to note that the “past-as-past” approach does not fit well with the picture we have developed here for X-marked desires. In the case of conditionals, “past-as-past” gave a plausible account for how domain widening happens in X-marked conditionals: at prior points in time, the set of accessible worlds (under both metaphysical and epistemic accessibility relations) is strictly larger/wider than it is at later points. But this doesn’t carry over neatly to desire ascriptions. First, it’s not strictly true that beliefs evolve monotonically, with doxastic sets at time \(t_{0}\) being subsets of those at a prior time \(t_{-1}\): people non-monotonically revise their beliefs in the face of new observations. One might say that grammar idealizes away from this and assumes that belief sets behave just like epistemic sets. A second problem for the past-as-past approach: we can X-mark desires even if there is no prior time at which the agent believed the desire to be attainable. Consider:

Surely, there is no time \(t_{-1}\) at which I believed that it was attainable that I wouldn’t be born.Footnote 60 A third problem: moving the evaluation point of a desire predicate into the past would not just move the determination of the domain (modal base) into the past, it would also move the time of the desire (the ordering source) into the past. But X-marked desires are not ipso facto about past desires.Footnote 61

8.2 X-marked necessity

We turn to the prospects of extending the Stalnakerian insight to X-marked necessity modals. In von Fintel and Iatridou (2008), we proposed that X-marking in this case is a signal about ordering sources. A strong necessity modal (like have to or must) has (at most) one ordering source and choosing the weak necessity modal (whether lexicalized like ought or transparently X-marked) signals that a “secondary” ordering source is active. Consider for example:

We suggested that have to in (82) depends on what is required by health and safety regulations, while ought in addition brings in what’s best by not legally binding common-sense recommendations. Rubinstein (2012, 2014) further developed our rather vague ideas and proposed (in effect) that X-marking signals that the ordering is sensitive to more than non-negotiable priorities.Footnote 62

This is a point where the theory of X-marking has serious trouble to provide a unified analysis. If the ordering source-based account for X-marked necessity is on the right track, it is hard to see how to view this as domain widening, since the domain is unaffected. It is also difficult to see how “past-as-past” can apply in this case.

The only way towards unification that we see is to recast what X-marking signals to encompass both domain widening (in conditionals and desires) and ordering source addition (in necessity constructions). The common denominator is that in all three cases, there is a certain kind of departure from a default setting:

- conditionals:

-

X marks widening of the domain beyond the default (= context/epistemic set)

- desire:

-

X marks widening of the domain beyond the default (= doxastic\(^{+}\) set)

- necessity:

-

X marks inclusion of priorities beyond the default (= non-negotiables)

Note that our earlier observation that X-marked necessity modals are “weakened” through X-marking while there is no sense in which X-marked desires are weak is captured by saying that X-marking targets different modal parameters in the two cases. An additional ordering source results in weakening, while a widened modal base does not.

9 After the prolegomena

These were the prolegomena, now comes the task of actually developing a full theory of X-marking. There is an excitingly vast to-do list.

9.1 To-do list

-

For each specific language, we sketched what initial ground work needs to be done in Sect. 1.4 (“The project”).

-

To assess the prospects of a unified meaning for X-marking, we need to fully understand the phenomena X-marking applies to. This is at least: conditionals, attitudes, modals, but also other uses of X-marking as discussed in Sect. 5.4. One thing to keep in mind is that analyzing the interaction of these constructions with X-marking will probably not only help us understand X-marking but also shed light on the linguistics of these constructions.

-

For conditionals, we listed some open questions in Sect. 3.4.

-

For attitudes and modals, there are also many open questions. We only sketched the barest outlines of how to approach the semantic analysis of these constructions, let alone their interaction with X-marking.

-

The issue of multiple (and possibly different) exponents of X-marking does not just arise with the antecedent versus consequent of conditionals, but also with X-marking on modal/attitudinal operators versus their complements. So, here as well, questions of effective versus reflective morphology will be relevant. Note that a “sequence of X-marking” approach would have to deal with the fact that some operators (like the Turkish keşke) trigger X-marking on their complement without (at least overtly) being X-marked themselves.

-

The composition of X-marking (for example, from past tense, imperfective aspect, and/or subjunctive mood) needs to be explored. For the particular case of “fake past”, we saw some reasons to think that a past-as-past approach is unlikely to be applicable in all cases. But past-as-modal (or hybrid) approaches may be feasible.

9.2 Conclusion

We conclude by restating the core insight we would like to put on the research agenda: the morphosyntactic category of X-marking corresponds to a notional category of “departure from a default value of a modal parameter”.

We admit that we have no idea whether a formal implementation of this picture is in reasonable reach. We leave this as an open challenge. One significant part of this will be to explain how this meaning of X-marking is composed in the many languages where X-marking is not atomic (unlike the seemingly simpler case of HungarianFootnote 63).

If the meaning of X-marking is “departure from a default value of a modal parameter”, why does it contain a past morpheme, an imperfective morpheme etc. in so many unrelated languages? The challenge of explaining the morphological composition of X will be formidable. If we are right about the contribution of X in the three different environments we have examined in this article, the task of explaining its compositional derivation will have to be on a quite different path than has been attempted so far, as the practice has been to explore X only in conditionals.

Our modest but, we believe, important point in this article was to show that studying X-marking in just one environment (conditionals) may give us a false sense of success and security. Once we broaden our attempts to understand X-marking in non-conditional environments, we see that all existing accounts fail. The past-as-past view appears to face serious difficulty. Maybe there is hope for the past-as-modal view.

Finally, it is of course possible that our ambition will be thwarted. Maybe it is correct that X-marking shows stable cross-linguistic tendencies of where it is used, but it may still be the case that the meanings it has in the different environments where it occurs cannot be unified. Future work will have to carefully assess with respect to specific languages whether a language-internal unified meaning can be shown to work and then whether those unified meanings are in fact the same cross-linguistically.Footnote 64

Notes

In fact, it is intriguing that each community seems to prefer a term that is a technical term in the other.

Virtually the same example appears in Karttunen and Peters (1979: ex. (4), p.6) without reference to Anderson’s article.

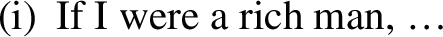

For some speakers, English retains the form were (instead of was) in antecedents of conditionals:

One might argue that (at least this variety of) English has a subjunctive but that its form has collapsed with the indicative in all but this small corner of the grammar. We might add that Stowell (2008) describes a variety of English with a form that he suggests is a subjunctive and that he dubs the “Konjunktiv II”, in homage to its more well-known German cousin:

Our glossing of non-English examples will be minimal, as a rule highlighting only morphological components relevant to X-marking.

We have not been able to establish a difference in meaning between the two forms.

A relevant example, provided to us by

(p.c.):

(p.c.):

Our use of the notion of a “notional category” is of course in homage to Kratzer (1981).

We thank a reviewer for prompting this clarification of our starting assumptions. The methodology we adopt is recommended by Matthewson (2001) and Bochnak (2013). [Added in proof:] Since writing this, we have indeed started to work on solidifying or refuting the proposal. In a manuscript in progress with the provisional title “If wishes were horses: What desire ascriptions have to do with conditionals”, we uncover some ways in which X-marking has slightly different effects in different languages.

All of the Hungarian data in this article are due to Dóra Kata Takács (p.c.).

The presence of the light verb/auxiliary merits a remark: many languages have the property of being able to carry only one morpheme on the verb, and the presence of an additional morpheme requires the addition of a light verb. This pattern can be seen very clearly in e.g. Hindi, a language completely unrelated to Hungarian.

As a reviewer points out, even the Hungarian case may not be entirely straightforward: there are two occurrences of the X-marking morpheme.

But it should be noted that fake imperfective is not a “perfective in disguise”. The imperfective form is a necessary ingredient of Greek X-marking but this form can also be interpreted as in progress:

Of course, with progressive interpretations, it is harder to show the “fakeness” of the imperfective, as that is the form one would expect anyway.

English X-marked conditionals can also contain other modals like might and, for some speakers at least, was going to (Halpert, 2011).

For the record, the relevant literature includes at least the following: (Iatridou, 2000; Nevins, 2002; Ippolito, 2003, 2013; Legate, 2003; Arregui, 2005, 2007; Schlenker, 2005; Han, 2006; Anand & Hacquard, 2010; Bittner, 2011; Halpert, 2011; Halpert & Karawani, 2012; Karawani & Zeijlstra, 2013; Schulz, 2014; Ogihara, 2014; Romero, 2014; Karawani, 2014; Ferreira, 2016; Bjorkman & Halpert, 2017; von Prince, 2019; Mackay, 2019).

Lest the reader think that English has no fake imperfective simply because it has no imperfective at all, we would like to point out that the question of the distribution of fake imperfective is more complex than that. For example, Russian, among other Slavic languages, has a fake past but no fake imperfective in the most standard X-marked conditionals. Yet, Russian is known for its many imperfectives. (The pointer to “standard X-marked conditionals” is because Grønn (2013) shows that there is a certain register used in annotations of chess games, in which Russian behaves like Greek and French, with its X-marking consisting of fake past and fake imperfective, instead of fake past and subjunctive by as in standard Russian X. See Iatridou & Tatevosov (2015) for a critique of Grønn’s analysis of “Chess Russian”.)

This was, in fact, the position taken for Greek imperfective in Iatridou (2000).

Stalnaker (2014: pp.175f). writes: