Abstract

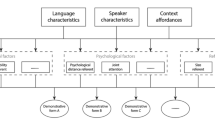

Deictic (or pointing) gestures are traditionally known to have a simple function: to supply something as the referent of a demonstrative linguistic expression. I argue that deixis can have a more complex function. A deictic gesture can be used to say something in conversation and can thereby become a full discourse move in its own right. To capture this phenomenon, which I call rich demonstration, I present an update semantics on which deictic gestures can indicate situations from a conversation’s context and those situations coherently connect to prior discourse to generate information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Brugmann (1904), Bühler (1934), and Frege (1956) for earlier discussions of indexicality.

For more recent analyses that depart from Kaplan (1989) in significant ways (involving e.g. the role of communicative intent), see Elbourne (2008), King (2001, 2008), Maier (2009), Roberts (2002) and Zeevat (1999).

As will become clear, the surface features of rich demonstrations such as hand shape or movement speed do not matter much for the purposes of this paper. I therefore limit the notation to rough timing and general description of the gesture. How a deictic gesture’s formal features affect the kinds of interpretations discussed here is an area for future research along the lines of what Ebert et al. (2020), Esipova (2019), Hunter (2019) and Schlenker (2018) have examined for iconic gestures. I discuss this and other directions for future research in Sect. 6.

Hunter et al. (2018) make a similar observation regarding the analogy to full assertions with respect to a different case, which I present in (5).

Strictly, Grice was not concerned with conditions for communication, only meaning. These are related, but distinct. See Neale (1992, Sect. 6) for a helpful discussion of Grice’s aims. Grice’s actual intentions aside, many have taken his observations to apply to communication as well as meaning.

In my view, the proposal put forward in this paper could apply to anything that would count as a direction of attention. I focus on deictic gestures as a starting point because this is where the phenomenon most naturally occurs, but one can imagine cases of non-gestural deixis that behave similarly. If instead of turning their arm the speaker in (2) showed a sign that read “I got a tattoo” or even said “look at my arm”, I think a rich demonstration would have been performed. I’m grateful to Philippe Schlenker for raising questions about this and for the former example, and to an anonymous reviewer for raising the same point.

Ebert and Ebert develop a view of gesture on which both iconic and deictic gestures have the exact same type of basal meaning (the establishment of a discourse referent with a property thematically related to ongoing speech). Their analysis does more to bring iconic gestures closer to the referential side of meanings than it does to bring deictic gestures closer to the iconic side of meanings. Nevertheless, on their view the core contribution of a deictic gesture is more complex than it is on traditional theories.

However I agree with Ebert et al. that the timing of a deictic gesture with respect to speech likely does have an effect on its interpretation.

This kind of claim is not new. For other theories that adopt the thought that discourse-level semantic/pragmatic explanations apply not only to linguistic communication but to gestures as well, see Abner et al. (2015), Benzi and Penco (2019), Kendon (1988, 2000, 2004, 2017), Schlenker (2020), and in particular for versions of this thesis that are thematically in-line with my approach: Hunter (2019), Hunter et al. (2018), Lascarides and Stone (2009a; b), and Stojnić et al. (2013). My view builds on these analyses, which articulate coherence-based explanations of iconic gesture interpretation. The novel point here is that larger mechanisms of interpretation apply to deixis in a way that returns full propositions.

Some approaches to discourse coherence informally make reference to situations (Hobbs , 1979; Kehler , 2002), but these do not explicitly apply a situation semantics as I do here. Hunter et al. (2018) formally incorporate events into their coherence-focused semantics, but do so in a way that differs from my use of situations in philosophically significant ways, which I discuss in Sect. 5.1.

This is related to a point made by Stojnić et al. (2013), who present a situation-based analysis of indexical reference resolution. While I focus on how an indicated situation can semantically impact a discourse, they focus on how a discourse can incorporate a situation without explicit indication via a gesture.

“Segments” because \({\mathcal {L}}\) should include anything that can function as an assertion, such as a meaningful sentence fragment.

For a complete treatment of situation semantics, see Devlin (2006).

To avoid situations, one could complexify the analysis of how objects are indicated, or of what it is to indicate an object, so as to make the inclusion of some property or collection of properties essential (cf. Ebert et al. 2020; Lücking et al. 2015). Such a route would still face difficulty in explaining cases like these, in which (i) something specific is communicated (e.g. an Explanation), even though (ii) the reason why it is true is unclear.

The approach outlined here does not encounter difficulties often associated with situation semantics. The criticisms from Soames (1985) of the semantic framework offered by Barwise and Perry (1983), for example, only takes hold if a possible worlds semantics is foregone. The Kratzerian position I offer here allows for possible worlds and situations to coexist.

For example: the assertion in (2) would be said in exactly same way as its counterpart (3a) in the linguistic version.

I am not making any meta-semantic claims. I use this gloss only as a way of tracking the concept of a discourse move, not as a description of what grounds an action’s status as a discourse move (or as communicative). For my purposes, it does not matter whether discourse moves constitutively involve intentions. Since they tend to pattern with intentions, this is a good way of understanding the idea.

Examples of convention-based understandings of coherence include Cumming et al. (2017), Lepore and Stone (2015), Stojnić (2018) and Stojnić et al. (2017). Approaches that conceptualize coherence relations as aimed at uncovering communicative intent include Hobbs (1979), Hobbs et al. (1993) and Kehler (2002). See Asher and Lascarides (2003, Ch. 3.3–3.6) for a discussion of some different approaches to coherence.

I’m grateful to an anonymous reviewer for helping to clarify the logical space of how my analysis might relate to NDU.

This could be spelled out in further formal detail along the lines of Lascarides and Stone (2009a).

The definition of CS update works for both assertive and demonstrative update because worlds are maximal situations. When x is a linguistic segment \(l \in {\mathcal {L}}\), the only worlds w such that \(\llbracket l \rrbracket \le w\) will be the very worlds in \(\llbracket l \rrbracket \). So in the case of assertion, the definition becomes equivalent to: \(CS_2 = CS_1 \cap \llbracket l \rrbracket \). For a demonstration, x is a gesture \(\delta \) that indicates a situation \(\llbracket \delta \rrbracket \), and the CS must only include worlds that have \(\llbracket \delta \rrbracket \) as a part.

In these representations of conversation states, c and g are omitted, as their updates are backgrounded and their contents impact the rest of K but not vice versa.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that a rich demonstration’s contribution is possibly at-issue when it is post-speech. I am open to this possibility, but am not yet convinced of anything decisive about the at-issue status of rich demonstration. Further research into the timing of deictic gestures is needed.

The number varies depending on the flavor of coherence theory. Hobbs (1979) and Kehler (2002) posit only a handful, Rhetorical Structure Theory (RST) (Mann and Thompson , 1988) utilizes around two dozen, and Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT) (Asher and Lascarides 2003) define over thirty. For simplicity I will mostly use the relations discussed by Kehler (2002), but nothing hinges on that.

Additionally, Explanation and Elaboration are defined to relate elements of the power set of \({\mathcal {M}}\). This is to account for cases in which e.g. explanations are given of entire existing discourse structures, in the sense of Asher and Lascarides (2003).

This is, of course, overly simple for an ideal definition of what the main situation of a sentence is. Modals, conditionals, implicatures, and more introduce difficult complications. I am inclined to think that these difficulties are related to those surrounding discourse topic discussed by Asher (2004). But the simple definition provided here should suffice for the purposes of this paper, since the sentences are quite simple and the focus is on how gestures interact with situations from speech and surrounding context.

Even though S is a partial function, it is a consequence of the definitions in Discourse Update v2 that every move (except discourse-initial ones) be coherently related to something else in the discourse: \(\forall m \in M : \exists \beta \in M \cup S, \exists \gamma \in {\mathcal {C}} \) such that \( \langle \langle m, \beta \rangle , \gamma \rangle \in S\) unless \(|M| = 1\).

As I discuss in the next section, the specific effects of a rich demonstration’s timing make for a clear next step for research.

This is also why for discourse-initial moves in each of these cases, I only represent a one stage update, even though technically two stages take place. It is just that the second stage returns a K identical to the intermediate K resulting from the first stage, since there are no constraints imposed by any coherence structure.

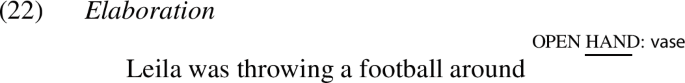

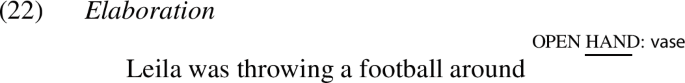

That is, the permutation wherein e.g. Explanation is operative when the gesture follows the utterance is pragmatically ruled out. Obviously the vase does not explain why Leila threw the football—that gets the causal relationship backward.

Note that this would also explain why grammatical changes are influential as well:

Though it may seem like this is a case of Result, it is actually Elaboration. Changing from the stative to the progressive forces the situation described to be one that contains the vase-breaking event to be a part of it, as opposed to caused by it (as with the main cases above). This is why it’d be natural to say “Leila broke a vase while throwing a football around”. This part-whole relationship is what is described by the Elaboration relation, and fortunately for the hypothesis, Elaboration is typically recognized as subordinating.

I’m grateful to an anonymous reviewer for emphasizing this point and initially articulating a QUD-based hypothesis.

References

Abner, N., Cooperrider, K., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2015). Gesture for linguists: A handy primer. Language and Linguistics Compass, 9(11), 437–451.

Anderbois, S., Brasoveanu, A., & Henderson, R. (2013). At-issue proposals and appositive impositions in discourse. Journal of Semantics, 32(1), 93–138.

Asher, N. (1993). Reference to abstract objects in discourse. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Asher, N. (2004). Discourse topic. Theoretical Linguistics, 30(2–3).

Asher, N., & Gillies, A. (2003). Common ground, corrections, and coordination. Argumentation, 17, 481–512.

Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Asher, N., & Vieu, L. (2005). Subordinating and coordinating discourse relations. Lingua, 115(4), 591–610.

Austin, J. L. (1956). If and cans. Proceedings of the British Academy, 42, 109–132.

Barwise, J., & Perry, J. (1983). Situations and attitudes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Beaver, D. I., Roberts, C., Simons, M., & Tonhauser, J. (2017). Questions under discussion: Where information structure meets projective content. Annual Review of Linguistics, 3(1), 265–284.

Benzi, M., & Penco, C. (2019). Nonlinguistic aspects of linguistic contexts. In G. Bella, & P. Bouquet (Eds.), Modeling and using context (pp. 1–13). Cham: Springer.

Brugmann, K. (1904). Demonstrativpronomina der Indogermanischen Sprachen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Buhler, K. (1934). Sprachtheorie. Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Jena: G. Fischer. English translation Theory of Language: The representational function of language (by D. F. Goodwin). Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1990.

Cumming, S., Greenberg, G., & Kelly, R. (2017). Conventions of viewpoint in coherence in film. Philosophers’ Imprint, 17(1), 1–29.

DeRose, K., & Grandy, R. (1999). Conditional assertions and ‘biscuit’ conditionals. Noûs, 33(3), 405–420.

Devlin, K. (2006). Situation theory and situation semantics. In D. M. Gabbay & J. Woods (Eds.), Handbook of the history of logic (pp. 601–664). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ebert, C., & Ebert, C. (2014). Gestures, demonstratives, and the attributive/ referential distiction. Paper presented at Semantics and Philosophy in Europe 7. Berlin, ZAS, June 28.

Ebert, C., Ebert, C., & Hörnig, R. (2020). Demonstratives as dimension shifters. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 24(1), 161–178.

Elbourne, P. (2008). Demonstratives as individual concepts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 31(4), 409–466.

Esipova, M. (2019). Composition and projection in speech and gesture. PhD thesis. New York University.

Frege, G. (1956). The thought: A logical inquiry. Mind, 65(259), 289–311.

Grice, H. P. (1957). Meaning. The Philosophical Review, 66(3), 377–388.

Grice, H. P. (1969). Utterer’s meaning and intention. The Philosophical Review, 78(2), 147–177.

Hobbs, J. R. (1979). Coherence and coreference. Cognitive Science, 3(1), 67–90.

Hobbs, J. R. (1990). Literature and Cognition . Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Hobbs, J. R., Stickel, M. E., Appelt, D. E., & Martin, P. (1993). Interpretation as abduction. Artificial Intelligence, 63(1–2), 69–142.

Hunter, J. (2019). Relating gesture to speech: Reflections on the role of conditional presuppositions. Linguistics and Philosophy, 42(4), 317–332.

Hunter, J., & Abrusán, M., et al. (2017). Rhetorical structure and QUDs. In M. Otake et al. (Eds.), New frontiers in artificial intelligence. (pp. 41–57). Cham: Springer

Hunter, J., Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2018). A formal semantics for situated conversation. Semantics and Pragmatics, 11, 10.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry, & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–565). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Kendon, A. (1988). How gestures can become like words. In F. Poyatos (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives in nonverbal communication (pp.131–141). Gottingen: Hogrefe.

Kendon, A. (2000). Language and gesture: Unity or duality? In D. McNeill (Ed.), Language and gesture, (pp. 47–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendon, A. (2017). Pragmatic functions of gestures. Gesture, 16(2), 157–175.

King, J. (2001). Complex demonstratives: A quantificational account. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

King, J. (2008). Complex demonstratives as quantifiers: Objections and replies. Philosophical Studies, 141(2), 209–242.

Kratzer, A. (1989). An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguistics and Philosophy, 12(5), 607–653.

Kratzer, A. (2002). Facts: Particulars or information units? Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5/6), 655–670.

van Kuppevelt, J. (1995). Main structure and side structure in discourse. Linguistics, 33(4), 809–833.

Lascarides, A., & Stone, M. (2009a). A formal semantic analysis of gesture. Journal of Semantics, 26(4), 393–449.

Lascarides, A., & Stone, M. (2009b). Discourse coherence and gesture interpretation. Gesture, 9(2), 147–180.

Lepore, E., & Stone, M. (2015). Imagination and convention: Distinguishing grammar and inference in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1979). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8(1), 339–359.

Lücking, A., Pfeiffer, T., & Rieser, H. (2015). Pointing and reference reconsidered. Journal of Pragmatics, 77, 56–79.

Maier, E. (2009). Proper names and indexicals trigger rigid presuppositions. Journal of Semantics, 26(3), 253–315.

Mann, W. C., & Thompson, S. A. (1988). Rhetorical structure theory: Toward a functional theory of text organization. Text, 8(3), 243–281.

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and Mind. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Murray, S. E. (2014). Varieties of update. Semantics and Pragmatics, 7(2), 1–53.

Neale, S. (1992). Paul Grice and the philosophy of language. Linguistics and Philosophy, 15(5), 509–559.

Roberts, C. (2002). Demonstratives as definites. In K. van Deemter & R. Kibble (Eds.), Information sharing. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics, 5(6), 1–69.

Schlenker, P. (2018). Gesture projection and cosuppositions. Linguistics and Philosophy, 41(3), 295–365.

Schlenker, P. (2020). Gestural grammar. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 38(3), 887–936.

Schlenker, P., & Chemla, E. (2018). Gestural agreement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 36(2), 587–625.

Simons, M., Tonhauser, J., Beaver, D., & Roberts, C. (2010). What projects and why. Semantics and linguistic theory 2010. Linguistic Theory, 20, 309–327.

Snider, T. (2017). Anaphoric reference to propositions. PhD thesis. Cornell University.

Soames, S. (1985). Lost innocence. Linguistics and Philosophy, 8(1), 59–71.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. In P. Cole (Ed.), Syntax and semantics 9: Pragmatics (pp. 315–322). New York: Academic Press.

Stojnić, U. (2018). Discourse, context and coherence: The grammar of prominence. In G. Preyer (Ed.), Beyond semantics and pragmatics (pp. 97–124). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stojnić, U., Stone, M., & Lepore, E. (2013). Deixis (even without pointing). Philosophical Perspectives, 27, 502–525.

Stojnić, U., Stone, M., & Lepore, E. (2017). Discourse and logical form: Pronouns, attention, and coherence. Linguistics and Philosophy, 40(5), 519–547.

Stone, M., & Stojnić, U. (2015). Meaning and demonstration. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 6(1), 69–97.

Syrett, K., & Koev, T. (2015). Experimental evidence for the truth conditional contribution and shifting information status of appositives. Journal of Semantics, 32 (3), 525–577.

Thomason, R. H. (1990). Accommodation, meaning, and implicature: Interdisciplinary foundations for pragmatics. In P. Cohen, J. Morgan, & M. Pollack (Eds.), Intensions in communication (pp. 325–363). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tonhauser, J. (2012). Diagnosing (not-)at-issue content. Proceedings of Semantics of Under-represented Languages in the Americas (SULA), 6, 239–254.

Txurruka, I. G. (2003). The natural language conjunction ‘and’. Linguistics and Philosophy, 26(3), 255–285.

Zeevat, H. (1999). Demonstratives in discourse. Journal of Semantics, 16(4), 279–313.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For very helpful discussion about and comments on this paper, I’m grateful to Josh Armstrong, Ian Boon, Catherine Hochman, Jessica Rett, Philippe Schlenker, Una Stojnić, Matthew Stone, the attendees of the 2019 Amsterdam Colloquium, and three anonymous reviewers. Special thanks to Sam Cumming and Gabe Greenberg for multiple rounds of extensive feedback. This paper is part of the Special Issue “Super Linguistics”, edited by Pritty Patel-Grosz, Emar Maier, and Philippe Schlenker.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

De Leon, C. Pointing to communicate: the discourse function and semantics of rich demonstration. Linguist and Philos 46, 839–870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09363-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-022-09363-0