Abstract

This essay calls attention to a set of linguistic interactions between counterfactual conditionals, on one hand, and possibility modals like could have and might have, on the other. These data present a challenge to the popular variably strict semantics for counterfactual conditionals. Instead, they support a version of the strict conditional semantics in which counterfactuals and possibility modals share a unified quantificational domain. I’ll argue that pragmatic explanations of this evidence are not available to the variable analysis. And putative counterexamples to the unified strict analysis, on careful inspection, in fact support it. Ultimately, the semantics of conditionals and modals must be linked together more closely than has sometimes been recognized, and a unified strict semantics for conditionals and modals is the only way to fully achieve this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I assume that there is some relatively systematic way of identifying counterfactual conditionals, and that, at some legitimate level of abstraction, counterfactual conditionals can be translated by a sentence of propositional logic containing two sub-clauses and a single logical connective. For discussion, see e.g. Kratzer (1986) and Lycan (2001, ch. 1).

The strict view has ancient roots, perhaps originating with the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus in the third century b.c.e. (Sanford 2003); it was first defended in the 20th century by C.I. Lewis (1914) and C.S. Peirce (1933). Contemporary, context-sensitive versions of the theory have been developed by Warmbrōd (1981a, 1981b), Lycan (1984, 2001), Lowe (1983, 1995), von Fintel (2001), and Gillies (2007).

The variable analysis was originally motivated by Stalnaker (1968) and Lewis (1973) with a range of non-monotonic data, such as Sobel sequences. Discourse-based treatments of strict conditionals by von Fintel (2001) and Gillies (2007) subsequently offered answers to these challenges, and replied with their own set of data—reverse Sobel sequences and their variants. This data has, in turn, been met with counter-explanations on behalf of the variable analysis (Moss 2012; Starr 2014b; Lewis 2017), and new challenges to the strict analysis (Lewis 2017; Nichols 2017). For an overview of the debate, see Moss (2012, §1, §2), Starr (2019, §2). Besides the variable and strict analyses of counterfactual conditionals, there are a variety of other competing accounts, including probabilistic analyses like those of Edgington (2003), Kvart (1986), Loewer (2007), or Leitgeb (2012); cotenability theories such as Goodman (1947), Daniels and Freeman (1980); or the arbitrary-selection approach of Schulz (2014). Unfortunately, discussion of these alternatives is beyond the scope of this essay.

On behalf of the variable theorist, I assume that the selection function normally returns a set containing more than one world (perhaps infinitely many); in other words the constraint known as Uniqueness is false. I’ll also make the Limit Assumption: for any sentence \(\phi \), and closeness ordering \(\ge _i\), if there are \(\phi \)-worlds ordered by \(\ge _i\), then there is at least one closest \(\phi \)-world according to \(\ge _i\). See Starr (2019, §2.3, §B) for discussion and references.

The definitions of the strict and variable analyses offered here constitute the semantic core of each view, but neither is limited to this core. A variety of additional constraints are commonly imposed. For example, besides Uniqueness and the Limit Assumption, various constraints are normally added to validate Modus Ponens. See Starr (2019, §2.3, §B). Further, by articulating the semantics in terms of truth-conditions here and throughout, I do not mean to exclude presuppositional or dynamic aspects of modal semantics. I’ll discuss these, along with additional pragmatic and discourse-based amendments as the need arises.

Another diagnostic is that, on the epistemic reading, synonymy is preserved if could have/might have is replaced by may have, but not so on the counterfactual reading.

It is not entirely clear whether Stalnaker and Lewis intended their \(\Diamond \), whose semantics they define, to be the translation of specific bare possibility modals in natural language, as the latter are not explicitly discussed in their original presentations. I will treat the various analyses of possibility modals as theoretical options for these authors, rather than firm commitments. For the analysis focused on in the text, Stalnaker (1968, 47) defines \(\Diamond \phi \) as a translation of \(\lnot (\phi >\lnot \phi )\), and adopts a variable analysis of the conditional. Thus \(\Diamond \phi \) is true at i iff it is not the case that the world in \(f(\phi ,i)\) is a \(\lnot \phi \)-world. But worlds in \(f(\phi ,i)\) could only be \(\lnot \phi \)-worlds if there are no ordered \(\phi \)-worlds, in which case \(f(\phi ,i)\) returns the absurd world, which verifies every sentence (p. 46). Thus \(\Diamond \phi \) is true iff \(f(\phi ,i)\) returns a non-absurd world. Transposed into the present framework, this would mean that \(\Diamond \phi \) is true iff \(f(\phi , i)\) is not empty. Lewis (1973, 22) reaches essentially the same analysis by similar means. Note finally that Stalnaker and Thomason (1970, 27–29) do invoke an accessibility relation to impose a background constraint on ordering, but they do not directly define the semantics of possibility modals in terms of accessibility, so I have omitted the complication here. Lewis (1973, 7–10) conceptualizes his system of spheres as a system of spheres of accessibility, so the conceptual elision is built-in.

Lewis (1973, 30–31) anticipates this analysis, characterizing it as an “inner” modality, in contrast with the “outer” modality of the max-analysis. Lewis (p. 31) credits Sobel with the observation that the two strengths of modal are definable in terms of the counterfactual.

In Kratzer’s (1981, 1991) system modals are defined by more than one parameter, including both a “modal base” and an “ordering source” (in the present nomenclature, an accessibility function and an ordering on worlds). Although the presentation here does contain two parameters, they are simply identified, so do not allow for the range of relations allowed by Kratzer. While that additional expressive flexibility may be important for defining the range of modal expressions, it won’t play a central role in the argument to come.

See, e.g. Yalcin (2007), Gillies (2010), Starr (2014a), Willer (2017). Nearly all of the data presented in Sects. 2 and 3 can be recapitulated for indicative conditionals. It is a separate question whether this data militates in the same way for the unified strict approach to indicatives. I discuss this issue in footnote 24.

Unless otherwise noted, the reader should assume that all examples in this essay are spoken by the same individual, and that this individual is speaking in some kind of deductive context—either reasoning to herself or trying convince an interlocutor of her conclusions.

Williamson (2007, 156) discusses this inference pattern, considered as a logical principle, under the name “NECESSITY”, formulated in terms of a necessity modal scoped over a material conditional: \(\Box (\phi \rightarrow \psi ) \rightarrow \phi > \psi \).

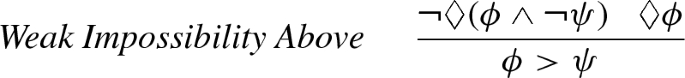

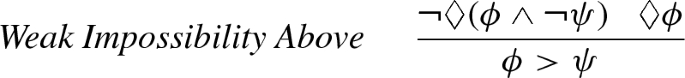

A qualification: recent advocates of the strict analysis have proposed that conditionals presuppose the compatibility of their antecedents with the possibilities made available by the context of evaluation (von Fintel 1998, 2; 2001, 15–20; Gillies 2007, 333–334). In the framework of this essay, this means that conditionals presuppose that their antecedents are compatible with the set of accessible worlds. If this principle is correct, and assuming presupposition failure leads to change in semantic value, then only a slightly weaker principle than IA is viable, namely:

But this does not disrupt the argument of the essay. The data which I cited as conforming with IA supports Weak IA just as well, and the unified strict analysis explains the inferential force of both by making both semantically valid.

The min-semantics assumes that \(k(i) = min(\ge _i)\); by Accessibility, then, \(max(\ge _i)\subseteq min(\ge _i)\); but since, by definition, \(min(\ge _i) \subseteq max(\ge _i)\), it follows that \(max(\ge _i) = min(\ge _i)\).

IB came to me via John Hawthorne’s 2008 metaphysics seminar at Rutgers University; he presented the inference in its inverted form, reasoning from \(\Diamond (\phi \wedge \lnot \psi )\) to \(\lnot (\phi >\psi )\).

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this fact pattern.

According to the max-semantics, \(k(i) = max(\ge _i)\). But according to Proximity, \(k(i)\subseteq min(\ge _i)\), hence \(max(\ge _i) \subseteq min(\ge _i)\). By definition, \(min(\ge _i) \subseteq max(\ge _i)\). So, in the ordering that results, \(min(\ge _i) = max(\ge _i)\).

To be clear, in Stojnić’s analysis, all modals are anaphoric; what I am calling “modal subordination” is, in Stojnić’s terms, modal anaphora to the most prominent possibility in the immediately preceding discourse.

The particle so blocks modal subordination in many contexts, but its overall behavior is complex. The following discourse is felicitous: “A wolf might walk in. It would be hungry. So it would eat you.” As is this: “If a wolf walked in, it would be hungry. So it would eat you.” But this variant is not: “A hungry wolf might walk in. So it would eat you.” It seems that the modally anaphoric behavior of so may be modulated both by discourse context and lexical encoding. In the text I focus on cases that are relevantly similar to the target examples.

Thanks to Una Stojnić (p.c.) for this example.

One might, for example, reconsider the data at hand in light of Schulz’s arbitrary selection theory of counterfactuals, an analysis more aligned with the variable than the strict analysis (Schulz 2014, §1). (Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for this idea.) Schulz suggests that might-counterfactuals and their dual would-counterfactuals are semantically compatible, but epistemically exclusive (2014, §3.3)—and as a consequence, one can’t felicitously assert both at the same time. The same strategy might be attempted for the IB-data discussed here, but this approach faces immediate problems. Schulz’s analysis crucially turns on the fact that might- and would-counterfactuals have the same quantified domain, the set of closest antecedent-worlds. But it is just this assumption that is challenged by the data I’ve presented here.

The dialectic here plays out somewhat differently for indicative conditionals. I believe the data favoring IB is just as robust for indicatives. But in many cases, the variabilist has a further pragmatic response at their disposal. In short: if indicative conditionals are variably strict, asserting \(\phi > \psi \) will, on plausible assumptions, have the pragmatic effect of eliminating all \(\phi \wedge \lnot \psi \)-worlds from the context set. As a result, on an analysis in which indicative (or epistemic) modals quantify over the context set, \(\lnot \Diamond \phi \wedge \lnot \psi \) will be true. These facts can be used to explain many forms of IB-supporting data for indicatives; whether it can be extended to all IB-supporting data requires further investigation.

I assume that the variable semantics follows either the k-semantics (+ Accessibility) or the max-semantics; see Sect. 3.3.

It is a remarkable fact that nearly the entire corpus of linguistic data surrounding the variable/strict debate (including, for example, Sobel and reverse Sobel sequences) has failed to control for the presence of discourse markers or test for their effects. It would be instructive to revisit these debates with this dimension of variation in mind.

To be clear, when I say here and below that the modal domain persists through discourse, I mean that, relative to a world of evaluation, the modal domain persists. What actually is carried forward in discourse is an accessibility function, or its equivalent.

A potential simplification of this analysis might hold that the presence of the Contrast discourse relation alone is sufficient to trigger modal accommodation. Yet it seems to me that infelicitous readings of the marked cases are (more) available when only the contrast marker is used (which is sufficient to incur Contrast), but not available when all three shift markers are employed. Thus the discourse relation of Contrast is necessary for triggering a domain shift, but that is not the whole story about the discourse mechanisms at play here.

Cf. Gillies (2007, 354), conjectures that the inferential marker so has a similar shift-blocking effect. In addition, von Fintel and Gillies (2018, 11–13) suggest that context shift is blocked between conjoined clauses prefixed by although, or embedded under suppose, or in the antecedent of a conditional.

See Moss (2012, §1–2) for a review of Sobel and reverse Sobel sequences.

Gillies (2007, 354) discusses a parallel case of (attempted) contraction with the marker of violated expectation still, in lieu of but, also noting its awkwardness. For me, variants with still are even easier to accommodate than those with but. Another violated expectation marker, nevertheless, seems to issue in a similarly effortless contraction of the modal domain. Moss (2012, 576) makes parallel observations about explicit signals like the clausal prefix “Oh come on.” These are subtle judgements that deserve further analysis.

References

Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, J. (2003). A philosophical guide to conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daniels, C., & Freeman, J. (1980). An analysis of the subjunctive conditional. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 21(4), 639–655.

Edgington, D. (2003). Counterfactuals and the benefit of hindsight. Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 12–27). London: Routledge.

Gillies, A. (2007). Counterfactual scorekeeping. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30, 329–360.

Gillies, A. (2010). Iffiness. Semantics & Pragmatics, 3, article 4, 1–42. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.4.

Goodman, N. (1947). The problem of counterfactual conditionals. Journal of Philosophy, 44(5), 113–128.

Hobbs, J. R. (1985). On the coherence and structure of discourse. Technical Report CSLI-85-37.

Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Knott, A. (1996). A data-driven methodology for motivating a set of coherence relations. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1986). Conditionals. Chicago Linguistic Society, 22(2), 1–15.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow, & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–650). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals: New and revised perspectives (Vol. 36). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kripke, S. (1963). Semantical considerations on modal logic. Acta Philosophica Fennica, 16(1963), 83–94.

Kvart, I. (1986). A theory of counterfactuals. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co.

Leitgeb, H. (2012). A probabilistic semantics for counterfactuals, part A. Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(1), 26–84.

Lewis, C. (1914). The calculus of strict implication. Mind, 23(90), 240–247.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers.

Lewis, D. (1979). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8, 339–59.

Lewis, K. S. (2016). Elusive counterfactuals. Noûs, 50(2), 286–313.

Lewis, K. S. (2017). Counterfactual discourse in context. Noûs, 52(3), 481–507.

Loewer, B. (2007). Counterfactuals and the second law. In H. Prince, & R. Corry (Eds.), Causality, physics, and the constitution of reality: Russell’s republic revisited (pp. 293–326). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lowe, E. (1983). A simplification of the logic of conditionals. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 24(3), 357–366.

Lowe, E. (1995). The truth about counterfactuals. The Philosophical Quarterly, 45, 41–59.

Lycan, W. (1984). A syntactically motivated theory of conditionals. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 9(1), 437–455.

Lycan, W. (2001). Real conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moss, S. (2012). On the pragmatics of counterfactuals. Noûs, 46(3), 561–586.

Nichols, C. (2017). Strict conditional accounts of counterfactuals. Linguistics and Philosophy, 40, 1–25.

Peirce, C. (1933). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Exact logic (Vol. III). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roberts, C. (1989). Modal subordination and pronominal anaphora in discourse. Linguistics and Philosophy, 12(6), 683–721.

Sanford, D. (2003). If P, then Q: Conditionals and the foundations of reasoning. London: Routledge.

Schulz, M. (2014). Counterfactuals and arbitrariness. Mind, 123(492), 1021–1055.

Stalnaker, R. (1968). A theory of conditionals. Reprinted in W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker, & G. Pearce (Eds.), Ifs. Conditionals, belief, decision, chance, and time (pp. 41–55). Dordrecht: Reidel, 1981.

Stalnaker, R., & Thomason, R. (1970). A semantic analysis of conditional logic. Theoria, 36(1), 23–42.

Starr, W. (2019). Counterfactuals. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. (Fall 2019 edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/counterfactuals/.

Starr, W. B. (2014a). Indicative conditionals, strictly. Ms., Cornell University.

Starr, W. B. (2014b). A uniform theory of conditionals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43(6), 1019–1064.

Stojnić, U. (2016). Content in a dynamic context. Noûs 53(2), 394–432.

Stojnić, U. (2017). One’s modus ponens: Modality, coherence and logic. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 95(1), 167–214.

Stone, M. (1997). The anaphoric parallel between modality and tense. Technical Report MS-CIS-97-09. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/177.

Stone, M. (1999). Reference to possible worlds. Technical Report RuCCS 49. https://www.cs.rutgers.edu/~mdstone/pubs/ruccs-49.pdf.

Txurruka, I. G. (2003). The natural language conjunction. Linguistics and Philosophy, 26(3), 255–285.

von Fintel, K. (1998). The presupposition of subjunctive conditionals. In U. Sauerland, & O. Percus (Eds.), The interpretive tract (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 25) (pp. 29–44). Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

von Fintel, K. (2001). Counterfactuals in a dynamic context. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language (pp. 123–152). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A. S. (2018). Still going strong. Ms., MIT and Rutgers University.

Warmbrōd, K. (1981a). Counterfactuals and substitution of equivalent antecedents. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 10(2), 267–289.

Warmbrōd, K. (1981b). An indexical theory of conditionals. Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review, 20(4), 644–664.

Willer, M. (2017). Lessons from Sobel sequences. Semantics & Pragmatics, 10, article 4, 1–57. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.4.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. New York: Wiley.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116(464), 983–1026.

Acknowledgements

This essay benefited from conversations with teachers and classmates at Rutgers University and students and colleagues at UCLA, as well as the comments of anonymous reviewers, an audience at the 2009 CEU Summer School on Conditionals, and the METH Philosophy of Language Group. Special thanks to Maria Bittner, Sam Cumming, Jeff King, Karen Lewis, Jessica Rett, Jason Stanley, Will Starr, Una Stojnić, and Matthew Stone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenberg, G. Counterfactuals and modality. Linguist and Philos 44, 1255–1280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09313-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09313-8