Abstract

The objective of our paper is to develop a workflow that allows us to calculate more accurate hypocenter locations in seismic event clusters of aftershock sequences or artificial events. Due to the increased sensitivity of the seismological instruments and density of the network, we are able to record small natural and artificial events. The discrimination of these events is necessary to investigate the recent tectonic movements in the Pannonian Basin. As a first step, we performed a hierarchical cluster analysis on the events in the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin using the spatial distances between the events to obtain event clusters. We selected 5 different test clusters from the list of clusters where two clusters consist of quarry blasts, another two consist of earthquakes, and the last one is a mixture of earthquakes and anthropogenic events. In the second step, to prepare for the double-difference multiple event location analysis, we manually revised the arrival time picks in the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin in order to increase the consistency and accuracy of the arrival times. We obtained improved single-event locations with the iLoc algorithm using the RSTT 3D global velocity model to provide initial locations for the double-difference relocation. We applied waveform cross-correlation at every station to obtain the differential times and correlation matrices. In order to discriminate the events in the mixed event cluster, we repeated the hierarchical cluster analysis, but this time, we used the correlation matrix as a distance metric. Examining the shape of the resulting dendrogram, it is clear that certain subclusters are well separated. In these subclusters, the coordinates of the events are close to the mines, where explosive quarrying takes place. With this technique, we are able to identify explosions that were listed as earthquakes in the catalogue.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The seismicity of the Pannonian Basin can be described as moderate. The recent seismic activity is caused by the Adriatic microplate’s movement, which rotates counterclockwise relative to Europe. Based on geophysical studies, the current stress field is typically characterized by compression (Bada et al. 1999; Gerner et al. 1999). The main active tectonic structures are flower structures (Fodor et al. 2005) linked to reactivated faults, shear zones. Additional geological structural studies require the most accurate earthquake catalogue. Nearly 40% of the Hungarian earthquakes are anthropogenic: quarry explosions and mine blasts. Hence, the earthquake catalogue may contain unidentified explosions that makes geological interpretation more difficult. In order to make the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin (HNSB, Gráczer et al. 2016) more accurate, it is necessary to identify these anthropogenic events.

In the routine observatory practice, a single-event location algorithm is used to calculate the hypocenter parameters, which often suffers from high uncertainty and location bias. The location errors can be significantly reduced by multiple event relocation methods combined with high-quality data. In this work, we use one of the most commonly used algorithms, the double-difference algorithm (Waldhauser and Ellsworth 2000).

2 Bulletin and data sources

The Kövesligethy Radó Seismological Observatory has been reporting events and phase data to the international data centers (e.g., ISC) since the beginning of the twentieth century. The annual Hungarian Earthquake Bulletin (HEB) publishing began in 1995 after the deployment of the Paks Microseismic Monitoring Network (PMMN; Tóth et al. 1996) operated by Georisk Earthquake Engineering. From 2002 to 2010, the HEB was published by the KRSO and the Georisk Ltd. collectively. Since 2011, data of all earthquakes detected by the Seismological Observatory have been collected and yearly published with detailed information in the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin (HNSB, Gráczer et al. 2016). Since 2014, magnitudes and event locations are determined with the iLoc location algorithm (Bondár and Storchak 2011) using the 3D global RSTT velocity model (Myers et al. 2010).

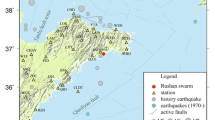

In our work, we have used all of the digitally registered seismic events between 2000 and 2016 in the Pannonian Basin; therefore, the relevant waveforms come from a wide range of sources. Figure 1 shows the stations we used in the analysis. The Hungarian National Seismological Network (HNSN, https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/HU/, doi:https://doi.org/10.14470/UH028726) operated by the Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geodetic and Geophysical Institute, Kövesligethy Radó Seismological Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (KRSZO), had various permanent stations at this time interval. We also used waveforms recorded by the temporary AlpArray Seismic Network (AASN, doi:https://doi.org/10.12686/alparray/z3_2015, Hetényi et al. 2018; Gráczer et al. 2018) that provides data from 1 January 2016, and by the Paks Microseismic Monitoring Network (PMMN, doi:https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/HM) operated by Georisk Ltd., as well as further permanent stations in neighboring countries.

As a result of the development of the station network, the amount of the data drastically increases over time. Figure 2 shows the number of waveforms we processed from the various networks.

3 Hierarchical cluster analysis and selected clusters

The HNSB contains 2802 events in the period between 2000 and 2016. The primary purpose of the hierarchical cluster analysis was to divide these events into smaller groups that would be suitable for the multiple event location method. We applied a single-linkage hierarchical cluster analysis (de Hoon et al. 2004; Sibson 1973) using the distance matrix constructed from the spatial distances between events. The single-linkage clustering method is agglomerative; every event is a cluster at the beginning of the clustering. In this case, the shortest distance is determined by a pair of single events that are closest to each other in different groups (nearest-neighbor linkage). The clusters are then sequentially merged into other clusters, until all events end up being in one large cluster. This produces a dendrogram where the events are ordered by their nearest-neighbor distance. Clusters are typically defined by manually cutting the dendrogram at a certain similarity level. However, instead of using a constant cutoff value, we applied the Dynamic Tree Cut method for automatically identifying clusters in a dendrogram (Langfelder et al. 2008). This method uses a dynamically changing height, which provides better results for complex dendrograms. Figure 3 shows the 84 clusters identified with the dynamic tree cut method. Figure 3 also indicates that an arbitrary constant cutoff value would not have been appropriate in this case.

Figure 4 shows the five test clusters we selected for multiple event relocation. Ground truth reference events (i.e., events known with at least 5 km location accuracy at 95% confidence level; Bondár et al. 2004; Bondár and McLaughlin 2009a) are necessary to evaluate the absolute error of the locations; therefore, we selected two clusters (C3 and C4) that contain mine explosions based on reported mine activities. Two clusters (C12 and C14) contain naturally occurring events, and the last cluster (C2) is a mixture of earthquakes and explosions. We also tested the method in the case of dense and poor station geometry in order to investigate the influence of the station distribution.

Map view of the 2802 clustered events (HNSB relocated with iLoc using the RSTT velocity model) after the dendrogram analysis. The most numerous clusters are indicated with different colors; the selected test clusters are framed and labeled. The C3 and C4 clusters consist of anthropogenic events; C12 and C14 are earthquake clusters. C2 has both types of events

The network geometry can be described by the secondary azimuthal gap (the largest azimuthal gap when leaving one station out from the network). Figures 5 and 10 show that for our test clusters, the secondary azimuthal gap (with respect to the cluster centroid) varies between 10 and 160°.

4 Waveform analysis

A significant part of the errors is caused by errors in the arrival time measurements (picking errors) as well as the inaccuracies in the applied velocity model. These errors constitute the data covariance matrix. The measurement errors are usually characterized as a Gaussian, zero-mean process (Billings et al. 1994; Pavlis 1986). However, the accuracy of the measurement depends on the signal to noise ratio, i.e., the accuracy of the arrival time measurements also depends on the magnitude (Kværna 1996) as arrival times picked consistently late with decreasing magnitude results in a heavy-tailed distribution of time residuals. It has been demonstrated that repicking the phases on the original waveforms could provide improvements over the bulletin picks in the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin (Czecze et al. 2018). In order to improve the quality of the arrival times, we revised all of the relocated events, on all available stations and waveforms. We used Seisgram2K (Lomax 1991) to pick arrival times. We filtered the waveforms with a band-pass filter where the frequency depended on the epicentral distance.

After repicking the phase arrivals, we performed waveform cross-correlation at each station. The correlation coefficient can quantify the similarity between the waveforms in each cluster, which later served as a basis for a second hierarchical cluster analysis. We performed correlations on the filtered vertical, radial, and transversal components of the seismograms and obtained P- and S- differential times on every station between all event pairs. We have determined the time window of the correlation using predicted arrival times from a local velocity model (Gráczer and Wéber 2012). We set the correlation threshold to 0.6 and discarded differential times below-threshold correlation coefficients. We also performed manual quality control to remove noise correlations from the database. We created SV, SH, and P correlation matrices at each station, because during the next hierarchical cluster analysis, the correlation coefficients serve as distance metrics. With the waveform cross-correlation, a significant amount of good-quality differential time data has been obtained and we noticed that man-made events had considerably more acceptable correlations than the natural events.

5 Initial locations

The double-difference algorithm requires the coordinates of the absolute initial locations. The Earth’s velocity structure is typically approximated by a 1D velocity model to calculate predicted travel times. In the case of complex tectonic structures, this can cause systematic travel-time prediction errors over certain raypaths, which may result in location bias. We relocated the events in the test clusters by the iLoc single-event location algorithm that is based on the ISC locator (Bondár and Storchak 2011). This algorithm accounts for the correlated travel-time prediction errors due to unmodeled velocity heterogeneities by using a priori estimation of the full data covariance matrix (Bondár and McLaughlin 2009b). Ignoring the correlated errors in travel-time estimates will lead to underestimation of the errors in determining the locations (error-ellipse) and could result in systematic location bias. The area of this study is geologically diverse, and it was previously shown that the RSTT 3D global velocity model (Myers et al. 2010) outperforms the 1D velocity models on all counts, and it is able to capture the major 3D heterogeneities in the area (Bondár et al. 2018).

6 Relocation with hypoDD

The double-difference algorithm (Waldhauser and Ellsworth 2000) is a relative event location method in which both absolute travel-time measurements and the P- and S-wave differential travel times from the waveform cross-correlation can be used. It combines the differential times from waveform cross-correlation and the differences between the arrival times of each phase in the bulletin data by minimizing double difference for each pair of events, specifying the vector difference between hypocenters. Therefore, there is no need for the use of station corrections. It determines the distance between correlating events within the cluster with the accuracy of differential times (phase correlation of P- and/or S-waves), and the distance between non-correlating events with the accuracy of ordinary travel-time measurements.

Relocation with hypoDD (Waldhauser 2001) is a two-step process. The first step involves analyzing the phase data, creating the travel-time differences between the earthquake pairs. The most important control parameters in hypoDD are the maximum distance between the event pairs and the stations and the maximum distance between the event pairs and the minimum number of measurements. Too strictly defined limitations might lead to the deletion of some events, and too-weak constraints might worsen the result of the relocation. Therefore, we ran a number of tests to fine-tune the parameters. Some percentage of the total number of pairs were considered outliers (with delay times larger than the expected delay time) and were removed from the data set.

The second step is to define the constraints used during the iterations. In the relocation process, we always used the P and S arrivals and differential times together. HypoDD can only use a 1D velocity model so we used a local velocity model (Gráczer and Wéber 2012). The program solves the double-difference equations iteratively by adjusting the model vector (hypocenter parameters) after each iteration. The equations are solved by the method of conjugate gradients (Paige and Saunders 1982) that solves the damped least squares problem, and requires a damping factor. This factor attenuating the model adjustment vector if it becomes unstable or the change in the hypocenter parameters is too big. This factor strongly depends on the condition number of the system. During the iterations, we applied different weightings, depending on the reliability of the data, and we gradually introduced the residual threshold and hypocentral separation limit. Until the solution became stable, an initial weighting was applied, and each iteration was performed with the re-weighted data and the weights were recalculated based on the distance between the events and the magnitude of the residuals. The iterations continued until the RMS residual dropped below the noise level of the data or the differences between the solutions were sufficiently small. In all cases, we assigned to S-phase data a lower initial weight (0.5) than to P-phase data (1.0), due to the higher uncertainty of measuring secondary phases.

Figure 6 shows the initial, iLoc, and final, hypoDD, locations for the two earthquake clusters (C14, C12). The C12 cluster was recorded by a poor network geometry, and in the final solutions, locations moved more than those in the C14 cluster with dense station coverage. The C12 cluster’s initial locations (Fig. 6 C12 a) has a north-south orientation due to the large secondary azimuthal gap. In both cases, the final double-difference locations significantly reduce the scatter in the initial locations.

a Initial hypocenter locations (map view) of the C12 and C14 clusters created with the iLoc algorithm using the RSTT velocity model after repicking phase arrivals. b hypoDD final solutions of the C12 and C14 clusters with differential times from waveform cross-correlation. Triangles represent the recording stations; filled red circles indicate the event locations

Figure 7 shows the relocations of explosion clusters. The quarry that produced the C3 cluster is situated on the border of Hungary and Slovakia (Fig. 8). The map view of the initial locations shows a strong NW-SE orientation, and the blasts are scattered in space (Fig. 7 C3 a). On the final results, the orientation is still present, but the relative position of the events has dramatically better clustered (Fig. 7 C3 b). Figure 8 shows that 4–5-km location bias is still present, possibly due to the 1D local velocity model. The C4 cluster also contains quarry blasts, but in this case, the geometry of the station network is more favorable. Nevertheless, hypoDD forms two subclusters (Fig. 7 C4 b) that can be identified with two distinct quarries.

a Initial hypocenter locations (map view) of the C3 and C4 clusters created with the iLoc algorithm using the RSTT velocity model after repicking phase arrivals. b HypoDD final solutions of the C3 and C4 clusters with differential times from waveform cross-correlation. Triangles represent the recording stations; filled red circles indicate the event locations

The depth of an event is usually the most difficult part of its location to calculate with great accuracy. If the depth is relatively shallow, it becomes more of an issue. In the HNSB, the depth of the recorded and known quarry blasts is fixed at 0 km since we are not able to determine a precise depth, but we know that the events are near the surface. In general, if there is a station that is closer than twice the depth, it can be determined with great accuracy. In this study, it is very rarely given due to the variable station geometry in time. Since the hypoDD does not allow us to fix the depth, and the C3 cluster consists of near-surface explosions, Fig. 9 can show the error of the hypoDD depth solutions.

Figure 9 also shows the depth distribution of the hypoDD solutions in the case of the C12 earthquake cluster. We assume that the depth of the transition zone between the brittle and ductile deformation is shallow (upper crust) in the Pannonian Basin due to the high geothermal gradient (Lenkey et al. 2002), and according to the iLoc solutions with the RSTT velocity model, the events are in the shallow brittle crust. However, relocalized hypocenters are deeper; thus, we will not provide depth solutions in this study.

7 C2 cluster

Our final test cluster in this study is C2 that consists of events that are identified in the HNSB as a mixture of earthquakes and explosions. Figure 10a shows that due to the very poor station geometry, significant location errors can be seen in the form of the north-south vertical line. Figure 10b shows that with such a poor station coverage, even hypoDD could not bring dramatic improvements.

a Station geometry around the C2 event cluster. The triangles represent the seismological stations. The primary azimuthal gap is marked by a red angle, and the secondary azimuthal gap is marked by the blue angle. b iLoc initial locations (black circles) and hypoDD solutions (red dots) of the C2 cluster. Grey squares indicate active mines

We performed a second hierarchical cluster analysis now using the correlation coefficients as distance metric. Note that during the waveform cross-correlation, the P, SV, and SH correlation matrices were created at each station.

For the C2 event cluster, we selected the closest stations to the cluster (KOVH, MORH). These stations recorded the majority of the events, some 95 of the 240 events in the cluster. We performed the hierarchical clustering with the correlation matrices taken as the distance matrix. Figure 11 shows well-separated subclusters in the correlation matrices for both KOVH and MORH. The correlation matrices were rearranged by the nearest-neighbor order obtained from the single-linkage cluster analysis. Figure 12 shows the dendrogram with the clearly identifiable subclusters. Figure 13 shows that the subclusters are geographically close to active quarries in Hungary and Croatia. Thus, even though hypoDD did not provide a dramatic location improvement, the cluster analysis using the correlation matrices allows us to associate these events to three separate quarries in the region.

In order to verify the anthropogenic origin of the subcluster events, we analyzed other parameters as well. First, we checked the event origin time. We can see on Fig. 14 that anthropogenic events (known explosions) usually occur between 5 a.m. and 4 p.m., and most of the subcluster events fall into the same time interval. Then, we made a chart about the event magnitudes also. Natural events follow the Gutengberg-Richter law, i.e., the relationship between the frequency and the magnitude of the earthquakes is reverse. In this case, the occurrence of the lower magnitude is less than the higher range; nearly 60% of the events have 1.7 magnitudes while 35% have smaller magnitudes.

After refining the clustering, we ran hypoDD for each subcluster again (Fig. 15). Based on the correlation matrix, the time-of-day distribution, and the magnitude now, we assumed that the blasts originated from closely related sources within the subclusters; thus, in this time, we used the cluster centroid as initial coordinates at the beginning of the hypoDD calculations instead of network sources. Subcluster 1 and 2 locations improved compared to the nearby mines. Figure 16 shows the unfavorable station geometry and the distribution of the used data around subcluster 3. Subcluster 3 is still located along the N-S orientation line, but the cluster gets much tighter.

8 Conclusions and discussion

We have performed single-linkage hierarchical cluster analysis on the entire seismicity of the Pannonian Basin and successfully applied the Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm (Langfelder et al. 2008) to identify event clusters. We selected five test clusters to demonstrate the feasibility of our methodology to relocate event clusters and possibly discriminate between earthquakes and explosions. In order to provide the best-quality data for the multiple event locations, we repicked all the phases for the test clusters in the Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin. We relocated the events with the state-of-the-art single-event location algorithm, iLoc, using the global 3D RSTT velocity model. For each cluster presented, the distribution of the depths of the events varies over a relatively large interval, but none of the selected clusters had a sufficiently close station for reliable depth determination. Note that for the known quarry blast, we fixed the depth to 1 km as hypoDD would not allow fixing the depth to zero. To obtain differential times, we performed waveform correlation; this step also allowed us to form correlation matrices at each station. The hypoDD relocations concentrate the initial locations into smaller clusters, and provide improved solutions for events determined even with unfavorable station geometry. Combining the differential times from waveform cross-correlation with absolute travel time significantly contributes to the accuracy of the final solutions. Despite the poor station geometry, the final solution of the C3 cluster is considerably more accurate than the original locations as the original NW-SE bias is almost completely eliminated. Even though the hypoDD analysis did not bring dramatic improvements for cluster C2, the cluster analysis using the correlation matrices as distance metrics allowed us to identify and associate events with active quarries and correctly reidentify them as explosions. Our methodology opens a way for a systematic analysis of event clusters in the Hungarian National Seismic Bulletin and helps in the discrimination between earthquakes and explosions and thus allows for a more reliable determination of the natural seismicity of the Pannonian Basin.

References

Bada G, Horváth F, Fejes I, Gerner P (1999) Review of the present-day geodynamics of the Pannonian basin: progress and problems. J Geodyn 27:501–527

Bondár I, McLaughlin K (2009a) A new ground truth data set for seismic studies. Seismol Res Lett 80(3):465–472

Bondár I, McLaughlin K (2009b) Seismic location bias and uncertainty in the presence of correlated and non-Gaussian travel-time errors. Bull Seismol Soc Am 99(1):172–193

Bondár I, Storchak D (2011) Improved location procedures at the International Seismological Centre. Geophys J Int 186(3):1220–1244

Bondár I, Myers SC, Engdahl ER, Bergman EA (2004) Epicenter accuracy based on seismic network criteria. Geophys J Int 156:483–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2004.02070.x

Bondár I, Myers SC, Engdahl ER (2014) Earthquake location. In: Beer M, Kougioumtzoglou IA, Patelli E, Au ISK (eds) Springer encyclopedia of earthquake engineering. Springer Verlag, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36197-5_184-1

Bondár I, Mónus P, Czanik C, Kiszely M, Gráczer Z, Wéber Z, the AlpArrayWorking Group (2018) Relocation of seismicity in the Pannonian Basin using a global 3D velocity model. Seismol Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220180143

Czecze B, Süle B, Bondár I (2018) A 2013. évi Heves megyei földrengéssorozat helymeghatározása többeseményes algoritmussal (Multiple event relocation of the 22 April 2013, ML = 4.8 Tenk (Hungary) earthquake aftershocks). Magyar Geofizika 58:162–174

de Hoon MJL, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S (2004) Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics 20:1453–1454

Fodor L, Bada G, Csillag G, Horváth E, Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger Z, Palotás K, Síkhegyi F, Timár G, Cloetingh S, Horváth F (2005) An outline of neotectonic structures and morphotectonics of the western and central Pannonian basin. Tectonophysics. 410:15–41

Gerner P, Bada G, Dövényi P, Müller B, Oncescu MC, Cloetingh S, Horváth F (1999) Recent tectonic stress and crustal deformation in and around the Pannonian basin: data and models. In: Durand B, Jolivet L, Horváth F, Séranne MS (eds) The Mediterranean basins: tertiary extension within the Alpine orogen, vol 156. Geological Society of London Special Publications, pp 269–294

Gráczer Z, Wéber Z (2012) One-dimensional P-wave velocity model for the territory of Hungary from local earthquake data. Acta Geodaetica et Geophysica Hungarica 47(3):344–357

Gráczer Z, Bondár I, Czanik CS, Czifra T, Győi E, Kiszely M, Mónus P, Süle B, Szanyi GY, Szűcs E, Tóth L, Varga P, Wesztergom V, Wéber Z (eds) (2017) Hungarian National Seismological Bulletin 2016, Kövesligethy Radó seismological observatory. MTA CSFK GGI, Budapest, p 353

Gráczer Z, Szanyi G, Bondár I, Czanik CS, Czifra T, Győri E, Hetényi GY, Kovács I, Molinari B, Süle E, Szucs V, Wesztergom Z, Wéber and AlpArray Working Group (2018) AlpArray in Hungary: temporary and permanent seismological networks in the transition zone between the Eastern Alps and the Pannonian basin. Acta Geodyn Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40328-018-0213-4

Hetényi G, Molinari I, Clinton J, Bokelmann G, Bondár I, Crawford WC, Dessa J-X, Doubre C, Friederich W, Fuchs F, Giardini D, Gráczer Z, Handy MR, Herak M, Jia Y, Kissling E, Kopp H, Korn M, Margheriti L, Meier T, Mucciarelli M, Paul A, Pesaresi D, Piromallo C, Plenefisch T, Plomerová J, Ritter J, Rümpker G, Sipka V, Spallarossa D, Thomas C, Tilmann F, Wassermann J, Weber M, Wéber Z, Wesztergom V, Zivcic M, AlpArray Seismic Network Team, AlpArray OBS Cruise Crew, AlpArray Working Group (2018) The AlpArray seismic network: a large-scale European experiment to image the Alpine Orogen. Surv Geophys 39:1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-018-9472-4

Kværna T (1996) Time shifts of phase onsets caused by SNR variations. NORSAR Sci Rep 2-95/96:143–152

Langfelder P, Zhang B, Horvath S (2008) Defining clusters from a hierarchical cluster tree: the Dynamic Tree Cut Package for R. Bioinformatics 2008 24(5):719–720

Lenkey L, Dövényi P, Horváth F, Cloetingh S (2002) Geothermics of the Pannonian basin and its bearing on the neotectonics. EGU Stephan Mueller Spec Publ Ser 3:29–40

Lomax AJ (1991) User manual for SeisGram. In: Lee WHK (ed) Digital seismogram analysis and waveform inversion, IASPEI software library volume 3. Seismological Society of America

Myers SC, Begnaud ML, Ballard S, Pasyanos ME, Phillips WS, Ramirez AL, Antolik MS, Hutchenson KD, Dwyer JJ, Rowe CA, Wagner GS (2010) A crust and upper-mantle model for Eurasia and North Africa for Pn travel-time calculation. Bull Seismol Soc Am 100:640–656

Paige CC, Saunders MA (1982) LSQR: sparse linear equations and least squares problems. ACM Trans Math Softw 8/2:195–209

Pavlis GL (1986) Appraising earthquake hypocenter location errors: a complete, practical approach for single-event locations. Bull Seismol Soc Am 76:1699–1717

QGIS Development Team (2018) QGIS geographic information system. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.osgeo.org

Sibson R (1973) SLINK: an optimally efficient algorithm for the single-link cluster method. Comput J 16:30–34

Tóth L, Mónus P, Zsíros T, Bondár I, Bus Z, Kosztyu Z (1996) Hungarian earthquake bulletin 1995, GeoRisk, Budapest, HU ISSN 1219-963X. https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/HM.

Waldhauser F (2001) hypoDD--A program to compute double-difference hypocenter locations. US Geol Surv Open File Report, 01 113

Waldhauser F, Ellsworth WL (2000) A double-difference earthquake location algorithm: method and application to the northern Hayward fault, California. Bull Seismol Soc Am 90(6):1353–1368

Wessel P, Smith WHF (1991) Free software helps map and display data. EOS Trans AGU 72:445–446

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Kövesligethy Radó Seismological Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Georisk Earthquake Engineering for providing all of the data, support, and software for the study. The reported investigation was financially supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (K128152, K124241, and 2018-1.2.1-NKP-2018-00007). The figures were prepared with QGIS Geographic Information System and Generic Mapping Tool (GMT, Wessel and Smith 1991).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Czecze, B., Bondár, I. Hierarchical cluster analysis and multiple event relocation of seismic event clusters in Hungary between 2000 and 2016. J Seismol 23, 1313–1326 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09868-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09868-5