Abstract

Asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are significant health problems that have disparate effects on many Americans. Misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis are common and lead to ineffective treatment and management. This study assessed the feasibility of applying a two-step case-finding technique to identify both COPD and adult asthma cases in urban African American churches. We established a community-based partnership, administered a cross-sectional survey in step one of the case-finding technique and performed spirometry testing in step two. A total of 219 surveys were completed. Provider-diagnosed asthma and COPD were reported in 26% (50/193) and 9.6% (18/187) of the sample. Probable asthma (13.9%), probable COPD (23.1%), and COPD high-risk groups (31.9%) were reported. It is feasible to establish active case-finding within the African American church community using a two-step approach to successfully identify adult asthma and COPD probable cases for early detection and treatment to reduce disparate respiratory health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma and COPD are obstructive respiratory diseases with a substantial impact on society. Although preventable and treatable, COPD, a combination of emphysema and chronic bronchitis, is irreversible and ranks third as a leading cause of death in the US [1, 2]. This debilitating disease affects 24 million Americans, half of whom remain undiagnosed [2, 3]. Asthma affects 20.4 million American adults, and although not always preventable, it can be controlled with appropriate medication and healthy management behaviors [6, 7]. For both diseases, poor diagnosis presents treatment challenges, compromises quality of life (QOL), and underestimates disease burden [3,4,5].

Racial disparities in Asthma and COPD are well documented [6,7,8,9,10,11]. African American adults have a higher prevalence of asthma and three times the likelihood of death compared to non-Hispanic Whites [7]. Although the prevalence and mortality from COPD are lower in African Americans, their COPD is often undiagnosed even at later stages or when diagnosed at younger ages, they tend to have a shorter smoking history [11, 12], have more comorbidities, worse disease severity, and poorer QOL [11,12,13,14,15]. These disparities have been attributed to underutilization of primary care, a lower likelihood of referral to a specialist or pulmonary rehabilitation, financial and structural barriers to care, lack of reference values for spirometry, beliefs, attitude, or the history of distrust for physicians and healthcare institutions [10, 14,15,15,17,18]. Efforts to improve health and reduce disparities in minority groups have embraced community-based efforts by actively reaching out to the people in their trusting environments [17,18,19,20,21,22]. The Faith-based Organization (FBO) is one community-based institution that plays an influential role in African American communities. FBOs have been effective avenues for delivering preventive health and were leveraged as centers for testing and vaccine distribution to combat the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic among minorities [19, 21,22,23,24,25].

Community-Based Approaches

Collaborative, community-based research (CBR) has been used to address community-identified needs and foster change in various contexts [26]. Such efforts have promoted the involvement of community members as partners in the planning and implementation of interventions or programs [27] that focus on environmental, social, economic, and cultural issues, linked to racial and geographical health disparities [28, 29]. FBOs are recognized for creating pathways to address such issues in the African American community [19, 20], where pastors have become stakeholders, advocates, motivators, and liaisons between their communities and researchers [18]. The pastors and other FBO leadership have been key in establishing research partnerships with health organizations and academic institutions [26].

Graham and colleagues collaborated with FBOs in Atlanta Georgia to provide respiratory assessment focused on asthma [22]. Other initiatives to improve asthma management have been implemented in collaboration with FBOs in the African American community [21, 30, 31], however, those for COPD are lacking. Targeted approaches such as active case-finding are recommended to improve COPD diagnosis in the primary care setting where spirometry, the test used to diagnose asthma and COPD, is underutilized [30,31,32,33,34,35]. One case-finding approach screens high-risk persons (with a smoking history) in a 2-step technique: step 1 symptom-based screening questionnaire; step 2 confirmatory spirometry in individuals with higher scores [36]. This 2-step technique has been used to diagnose COPD in pharmacies [37], and primary care practices [38, 39], and to diagnose asthma at schools [40], and churches [22]. This study assessed the feasibility of identifying both COPD and asthma cases using the 2-step case-finding approach in urban African American churches. These findings can be useful to inform future initiatives within the African American community by leveraging resources within the church to facilitate early detection of diseases and thus reduce health disparities in COPD and asthma.

Methods

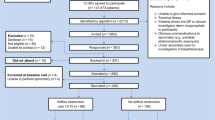

The 2-step case-finding approach involved developing community-based partnerships with the church leaders and representatives, administering a cross-sectional survey to the members of the congregation, and providing spirometry testing to self-reported asthma and COPD cases and those at risk.

Participants

African Americans 18 years and older from four urban churches were invited to participate. Churches were recruited by the lead pastor, were predominantly Baptist, and 3/4 were located in the same zip code. On average, two churches had 80–100 members, while the other two had 300 members. The study was approved by the Kent State University Institutional Review Board.

Establishing the Partnership and Recruitment

The partnership between the churches and the academic institution was initiated after one pastor concerned about the self-reported smoking status of his congregation contacted a faculty and mobilized three other pastors. Four planning meetings were held to establish relationships and define the relevant approach for recruitment and intervention (Table 1). The first meeting with the lead pastor resulted in establishing the program’s purpose, defining roles and responsibilities, and identifying resources at the churches and educational institution. It was determined that a representative from each church would serve as a liaison to the researchers. Before the next meeting, the faculty assembled a research team at the educational institution, while each pastor identified at least one liaison from his church. The lead pastor, two liaisons, and two research team members held a second meeting to establish the overall approach of the program, outline recruitment strategies, and major program activities. Early discussions allowed the liaisons to review planned church activities and determine how to integrate and schedule program activities. All six liaisons were female and 45 years or older. Four had asthma, of which one was a former smoker. One had COPD and an occasional smoker. Four of the liaisons were members of their Church’s Nurses Ministry (CNM). The CNM is an established health ministry characteristic of predominantly African American churches [41]. The research team identified the screening tools for both diseases and included demographic items to create the survey for step 1. The team also developed promotional materials, i.e., pamphlets, handouts, church announcement scripts, and posters, and shared them with the liaisons for feedback. At the third and fourth meetings, the liaisons, lead pastor and a representative from the research team finalized the materials and scheduled the distribution of surveys at each church. The initiative became the asthma-COPD (ACOPD) program aimed at fulfilling three main functions: (1) administering a survey to identify church members with self-reported asthma or COPD, probable disease, or a smoking history, (2) conducting health screenings, and (3) implementing an intervention consisting of education and text-messaging (Fig. I—Supplementary materials). The faculty used existing relationships to recruit a local health system as a partner to perform spirometry testing. Five meetings were held with six Respiratory Therapists (RTs) to determine health screening procedures and two RTs volunteered for ACOPD program activities.

Prior to administering surveys, at least two visits were made to distribute study-related information at each church. The pastors actively participated in recruitment by making announcements from the pulpit, while liaisons distributed promotional material and used word of mouth. Two rounds of events (survey administration and health screening) were held on Sundays over four months. Respondents who self-reported provider-diagnosed asthma or COPD, a smoking history, or scored higher on the screening tools, and provided their contact information as an indicator of interest in subsequent program activities, were called and invited to the health screenings held over three months.

Data Collection

The Two-Step Case-Finding Technique

Step 1—Screening tools: Surveys were administered to consenting participants after Sunday service and at other church events including Saturday missions outreach. Graduate students and church nurses ministry members (CNMMs) assisted with administering surveys after being trained on scoring the screening tools. Surveys were distributed on two consecutive Sundays at each church.

Step 2—Spirometry testing: Participants who provided contact information in step 1 were invited for screenings. This step included confirmatory diagnosis via spirometry if they self-reported provider-diagnosed asthma or COPD or identified as probable cases based on step 1. Nursing students and CNMMs conducted blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), and glucose screenings, while Master of Public Health graduate students administered the survey, engaged attendees, and handled logistics. The RTs performed spirometry testing based on the American Thoracic Society guidelines [42] using the Medgraphics portable and the NDD EasyPlus screener. Up to two consistent spirometry readings were performed for each participant.

Percent forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced volume capacity (FVC) ratios (FEV1/FVC) were obtained. FEV1 is the volume of air exhaled during the first second of maneuver and FVC is the measure of air forcibly exhaled from the point of maximal expiration [1]. While participants were seated upright, a minimum of two FVC maneuvers were attempted for reliability. Time constraints, tolerance, and understanding of maneuver led to reporting the best attempt for the FEV1/FVC ratio. Screening results were shared with participants on a health card, and those with abnormal tests were encouraged to discuss results with their healthcare provider. Current smokers were encouraged to quit and provided a handout with quit resources.

Measures

The Survey

The survey included the validated Asthma Screening Questionnaire (ASQ) for adults [43], and the COPD-Population Screener (COPD-PS) [44]. Questions on demographics, medical history (obesity, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes), smoking history, insurance, flu vaccine, and having a personal provider, were included as well as a request for contact information. The survey was reviewed for content validity and face validity by researchers and two CNMMs. COPD risk based on smoking status was determined by the question, “Are you a: non-smoker (never smoked), occasional/someday smoker (smokes, but not daily), current smoker (smokes daily), or former smoker (quit smoking)” [45].

Case Definition

COPD cases included participants with (1) provider diagnosis of either COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis or (2) spirometry FEV1/FVC ratio < 70% obtained at the screening events where probable cases were identified based on the COPD-PS (range 0 to 10) with a cut off ≥ 5 points [44]. COPD at-risk were participants that self-identified as current, occasional, or former smokers [45]. Asthma cases included participants with a provider diagnosis of asthma, while probable asthma cases were determined using the ASQ (range 0 to 20). The cutoff was selected based on previous research showing ≥ 4 points resulting in 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity [43].

Analysis

Univariate descriptive analysis were employed to summarize our sample characteristics (averages and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). Independent t-test and chi-square analysis were used to examine bivariate relationships between sample variables. All data management and statistical analysis were performed in SAS, version 9.3. We excluded survey respondents with ≥ 50% missing data (n = 11).

Results

The ACOPD Partnership

The ACOPD program was implemented through a collaboration between seven partners (four churches, two departments at the academic institution, and a local health system). The program reach impacted over 200 church members and promoted awareness of respiratory health through surveys and five health screening events that reached 141 people who received 322 screenings (Table 2). Five pastors, six liaisons, two RTs, and 24 nursing and graduate student volunteers were engaged through program activities (Fig. I—Supplementary Materials).

Disease Estimates

In total, 219 surveys were completed. Respondents reported an average (SD) age of 53 (± 16) years, were predominantly female (78.4%), African American (98.1%), and had insurance (93.8%) (Table 3). Approximately 33% of respondents had a smoking history including 48 former smokers (23.4%) and 27 current smokers (13.2%). The average number of smoke-years was 24 (± 13.8) among smokers who responded (n = 22) to the question, ‘For current smokers, how many years have you smoked cigarettes [45]?’ There was a significant difference in the asthma (Males: 1.6 ± 2.9, Females: 3.2 ± 4.5, p = 0.032) and COPD (Males: 2.9 ± 2.2, Females: 3.9 ± 2.8, p = 0.032) screening scores as well as uptake of the flu vaccine in the previous 12 months (Males: 13(28.9%), Females 85(52.1%) p = 0.016).

Physician diagnosed asthma was reported by 25.9% (n = 50), of which 8 participants reported no symptoms. Of all participants (n = 51) who scored ≥ 4 on the ASQ, 39.2% (20/51) had no physician diagnosis, indicating probable asthma. Overall, 9.6% reported physician diagnosed COPD (Fig. II-Supplementary Materials). Based on the COPD-PS, 23.1% (36/156) scored ≥ 5, indicating probable COPD. In the non-COPD group, 31.9% were classified as high-risk (smoking history with no physician diagnosis of COPD). Self-reported provider diagnosis was high for obesity 59 (32.2%) and CVD 59 (30.6%) (Table 4). Females were more likely to be obese (56 (34.4%) vs. 3(6.7%), p = 0.002), have asthma (46(28.2%) vs. 4(8.9%), p = 0.008), and be probable asthma cases (16(9.8%) vs. 4(8.9%), p = 0.021).

Discussion

Utilizing the two-step case-finding technique to identify cases of asthma and COPD and risk of COPD was feasible through a partnership between the African American churches and researchers from an academic institution. This suggests that FBOs remains a significant pillar for effective health initiatives within the African American community. In this study, pastors and church representatives bridged community needs and resources at the academic institution to raise awareness of health issues (COPD) often overlooked or perceived as less severe in the African American community. Such community-institution partnerships continue to drive implementation of culturally tailored interventions in an effort to reduce health disparities [41] linked to comorbid conditions prevalent in African Americans [19, 20]. Asthma programs have been implemented within the African American church [19, 22, 30]; however, community-based programs for COPD are lacking and African American representation in studies is poor [46, 47]. The lack of efforts is important given that African Americans with COPD report poorer QOL, greater frequency of exacerbations, and more emergency department utilization compared to non-Hispanic Whites [48].

CNM members played a vital role in implementing program activities. Churches with a health ministry often organize health events [24] in collaboration with academic institutions, local health agencies, or other churches [49]. An established health ministry is an indicator of commitment to the health and well-being of a congregation and can facilitate research interventions for underrepresented minorities. Within the CBR approach, such community-institution research partnerships demand trust, which was cultivated in this study through continuous engagement, open communication, and mutual flexibility while developing program activities [49].

Trained pharmacists used a similar case-finding technique to identify COPD cases in an at-risk population across Australia [37]. They recruited individuals with a smoking history to complete a COPD risk assessment, undergo a lung function test, and follow-up with a general practitioner as indicated by results (15 participants (10%) were diagnosed after referral). A Mexico-based study performed initial screening using a questionnaire and a pocket spirometer followed by confirmatory spirometry for the individuals found at highest-risk [38]. Use of such active case-finding techniques can improve early detection and allow for appropriate use of resources by testing only those with symptoms as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [50, 51].

The proportion of provider-diagnosed asthma cases (26%) from our study was more than double the national prevalence estimates for African Americans (11.6%) [14, 52] and was twice that found in two church studies (13% and 15%) [21, 31]. The higher asthma estimates in our study could be explained by the larger proportion of elderly women in whom asthma and reduced lung function is more common due to older age and biological factors [2, 13]. Additionally, the women who underwent spirometry had a significantly higher BMI than the men (33.4 ± 7.1 vs. 29.5 ± 6.7 p = 0.016), and were mostly in class I (20/65(30.8%)) or III (16/65(16%)) of obesity (Table 5), which is a known risk factor for asthma [13, 53]. For COPD, comparable data specific to the African American church community are unavailable; however, the national prevalence rates of COPD is lower, 6.1% compared to our study estimates (9.6%) [54, 55]. This may be due to our predominantly older female sample and the decreasing prevalence of COPD in men and stable prevalence in women [56]. One report found a 6.1% COPD prevalence among women vs. 4.1% among men between 2007 and 2009 [56], supporting that women experience higher burden.

In the current study, 29.5% (46/156) of participants were considered probable cases of COPD based on COPD-PS scores of ≥ 5. Of those, 78.3% (36/46) did not report a COPD diagnosis, indicating possible undiagnosed cases. This was not surprising given previous reports of underdiagnosis associated with COPD [57, 58]. Eight percent (7/92) who underwent spirometry had poor lung function characteristic of COPD (FEV1/FVC < 70%) [1]. These participants were recommended to get additional lung function tests to confirm COPD given that 3/7 were > 70 years of age, an age over which caution is advised during COPD diagnosis [1].

Study Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted while considering the following limitations. The screening survey was named ‘The Asthma & COPD Prevalence Survey,’ which may have been so specific it influenced who chose to complete the survey. Individuals who had neither disease nor concern for the conditions may have been less inclined to complete the survey, biasing the sample towards those with respiratory issues and concerns, resulting in higher estimates. However, all church members were encouraged to complete the survey and attend the events where other preventative health screenings were available. Further, disease estimates may suffer from self-report bias. Employing the two-step case-finding technique was intended to address this potential bias by verifying survey results with spirometry testing. However, since the health screening events were held after church service, time was a barrier to program implementation. Once church service was over, a large volume of participants arrived at the screening event simultaneously, leading to unanticipated wait for screening services. It took on average 45 min to get all four screenings, with about 10–15 min for spirometry. Church members, though willing to participate, explained departure due to other engagements. Not all probable cases received spirometry testing as planned while some who self-reported asthma or COPD lacked confirmatory spirometry measures. The majority of participants were able to complete a minimum of two screenings, BP (26.1%, 84/322) and glucose (26.7%, 86/322). Where trained technicians or RTs are available in the church setting, screening surveys and spirometry should be done at one event [22]. This could mean organizing the event on other days besides Sunday, having a series of events, collaborating with more churches and RTs [22], or scheduling testing at a local health facility. Nevertheless, this approach may result in lower attendance as the after service event was deemed convenient by the liaisons as it capitalized on people being at the location of the event, thus eliminating transportation barriers.

Study Strengths

A major strength of this study was the ability to screen and provide early detection of respiratory problems to a FBO population in a convenient setting. Engaging trained CNMMs (liaisons) in the screening process was also significant as they offer an avenue for sustainability of screening and referral activities. Raising awareness and recruiting participants from the community setting may reach a different subset of asthma and COPD patients with mild or intermittent symptoms, a group that can benefit significantly from self-management interventions, which can prevent accelerated decrease of lung function, and reduce healthcare costs. The majority of respiratory interventions recruit participants from hospitals or pulmonary rehabilitation facilities, leading to study samples with moderate to severe asthma or COPD [59, 60]. Granted that patients with greater disease severity require more attention in terms of treatment and disease management, those with minor symptoms or those at high risk later develop more severe forms of the diseases if not well managed. Also, early stages of COPD may be asymptomatic to mildly symptomatic with a ‘nagging cough’ often interpreted as a ‘smoker’s cough’, and usually goes unreported to healthcare providers [61].

Conclusion

It is feasible to identify both COPD and asthma cases using the 2-step case-finding approach in urban African American churches. The church continues to be a catalyst towards eliminating health disparities in the African American community. There is significant benefit in continuously identifying community needs, assessing resources, and collaboratively engaging in relevant efforts with diverse community partners to advance health. Our study results indicate important lessons and warrants trained CNMMs as partners in active case-finding by administering respiratory screening tools and giving recommendations on deliberate discussions with healthcare providers. Long-term, this approach has potential to improve early detection, health outcomes, and QOL in African Americans with asthma or COPD.

New Contribution to the Literature

This research demonstrated the feasibility of using the church, a trusted entity within the African American community as a case-finding setting for COPD, a poorly diagnosed disease partly due to suboptimal use of spirometry testing in the clinical setting. The involvement of trained CNMMs is especially novel as it enhances the influence of churches in the promotion and sustainability of implemented health activities. The CNMMs often have a professional background in healthcare, thus a potential resource for health promotion. This study demonstrates that it is feasible to identify African Americans with COPD at FBOs, in partnership with CNMs, an effort that can contribute to reducing respiratory health disparities.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, management, and prevention. A guide for health care professionals: global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2019.

American Lung Association. How Serious Is COPD | American Lung Association. 2019. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/learn-about-copd. Accessed 19 Jan 2021.

Diab N, Gershon AS, Sin DD, et al. Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(9):1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201804-0621CI.

Kavanagh J, Jackson DJ, Kent BD. Over-and under-diagnosis in asthma. Breathe. 2019;15(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0362-2018.

Wu AC, Greenberger PA. Asthma: overdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, and ineffectively treated. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):801–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2018.02.023.

McCracken JL, Veeranki SP, Ameredes BT, et al. Diagnosis and management of asthma in adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;318(3):279–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.8372.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Environmental Health. Most Recent National Asthma Data. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm. Accessed 20 Mar 2021.

Schraufnagel D, Blasi F, Kraft M, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Policy Statement: disparities in respiratory health. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(4):906–15. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00062113.

Celedón JC, Roman J, Schraufnagel DE, et al. Respiratory health equality in the United States: The American thoracic society perspective. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(4):473–9. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-059PS.

Ejike CO, Dransfield MT, Hansel NN, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in America’s black population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(4):423–30. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201810-1909PP.

Mamary AJ, Stewart JI, Kinney GL, et al. Race and gender disparities are evident in COPD underdiagnoses across all severities of measured airflow obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(3):177–84. https://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0145.

Martinez CH, Mannino DM, Jaimes FA, et al. Undiagnosed obstructive lung disease in the United States. Associated factors and long-term mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(12):1788–95. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-388OC.

Kamil F, Pinzon I, Foreman MG. Sex and race factors in early-onset COPD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(2):140–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835d903b.

Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Trends and patterns of differences in chronic respiratory disease mortality among US counties, 1980–2014. JAMA. 2017;318:1136. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11747.

Putcha N, Han MK, Martinez CH, et al. Comorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African Americans. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1(1):105–14. https://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2014.0112.

Arnett M, Thorpe R, Gaskin D, et al. Race, medical mistrust, and segregation in primary care as usual source of care: findings from the exploring health disparities in integrated communities study. J Urban Health. 2016;93(3):456–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0054-9.

Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, et al. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):642–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:537–46. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1525-1497.1999.07048.X.

DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, et al. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030.

Torrence WA, Phillips DS, Guidry JJ. The assessment of rural African-American Churches’ capacity to promote health prevention activities. Am J Health Educ. 2005;36(3):161–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2005.10608178.

Berkley-Patton J, Thompson C-B, Bradley-Ewing A, et al. Identifying health conditions, priorities, and relevant multilevel health promotion intervention strategies in African American churches: a faith community health needs assessment. Eval Program Plann. 2018;67:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.10.012.

Harris D, Graham L, Teague G. Not one more life: a health and faith partnership engaging at-risk African Americans with asthma in Atlanta. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(4):421–5. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-166IP.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, et al. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016.

Holt CL, Graham-Phillips AL, Daniel Mullins C, et al. Health ministry and activities in African American faith-based organizations: a qualitative examination of facilitators, barriers, and use of technology. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):378–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0029.

Brewer LC, Asiedu GB, Jones C, et al. Emergency preparedness and risk communication among African American churches: leveraging a community-based participatory research partnership COVID-19 initiative. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200408.

Strand K, Marullo S, Cutforth N, et al. Principles of best practice for community-based research. MJCSL. 2003;9(3):5–15.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173.

McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, et al. Community-based interventions. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):529–33. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.4.529.

Anderson L, Adeney K, Shinn C, et al. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2.

Ford ME, Edwards G, Rodriguez JL, et al. An empowerment-centered, Church-based Asthma Education Program for African American Adults. Health Soc Work. 1996;21(1):70–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/21.1.70.

Whitt-Glover MC, Porter AT, Yore MM, et al. Utility of a congregational health assessment to identify and direct health promotion opportunities in churches. Eval Progr Plan. 2014;44:81–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.02.005.

Chapman KR, Boulet LP, Rea RM, et al. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):320–5. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00039707.

Bourbeau J, Sebaldt RJ, Day A, et al. Practice patterns in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary practice: the CAGE study. Can Respir J. 2008;15:13–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/173904.

Blain E, Craig T. The use of spirometry in a primary care setting. Int J Gen Med. 2009;2:183–6. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.s7319.

Walters JA, Walters EH, Nelson M, et al. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of COPD in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(4):396–402. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00039.

Jordan RE, Adab P, Sitch A, et al. Targeted case finding for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease versus routine practice in primary care (TargetCOPD): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(9):720–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(16)30149-7.

Fathima M, Saini B, Foster J, et al. Community pharmacy-based case finding for COPD in urban and rural settings is feasible and effective. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2753–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S145073.

Franco-Marina F, Fernandez-Plata R, Torre-Bouscoulet L, et al. Efficient screening for COPD using three steps: a cross-sectional study in Mexico City. NPJ Primary Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14002. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.2.

Dirven JAM, Tange HJ, Muris JW, et al. Early detection of COPD in general practice: patient or practice managed? A randomised controlled trial of two strategies in different socioeconomic environments. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(3):331–7. https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00070.

Gerald LB, Redden D, Turner-Henson A, et al. A multi-stage asthma screening procedure for elementary school children. J Asthma. 2002;39(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1081/JAS-120000804.

Brewer LC, Balls-Berry JE, Dean P, et al. Fostering African-American Improvement in Total Health (FAITH!): an application of the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7™ among Midwestern African-Americans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:269–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0226-z.

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–38. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805.

Shin B, Cole SL, Park S-J, et al. A new symptom-based questionnaire for predicting the presence of asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20(1):27–34.

Martinez FJ, Raczek AE, Seifer FD, et al. Development and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS). COPD. 2008;5(2):85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412550801940721.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/1997-2018.htm. Accessed 20 Mar 2021.

Chamberlain AM, Schabath MB, Folsom AR. Associations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with all-cause mortality in Blacks and Whites: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(3):308–14.

The National Black Church Initiative. National black Church initiative: twelve-week COPD Demonstration Project.

Han MK, Curran-Everett D, Dransfield MT, et al. Racial differences in quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest. 2011;140(5):1169–76. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2869.

Strand K, Marullo S, Cutforth N, et al. Community-based research and higher education: principles and practices. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass; 2003.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed 08 Mar 2021.

DeJong SR, Veltman RH. The effectiveness of a CNS-led community-based COPD screening and intervention program. Clin Nurse Spec. 2004;18(2):72–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200403000-00012.

Hornbeck C, Kollman J, Payne T, et al. The Impact of Chronic Disease in Ohio: 2015: Ohio Department of Health, Chronic Disease Epidemiology and Evaluation Section Bureau of Health Promotion;2015.

Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Qin X, et al. Assessing asthma control and associated risk factors among persons with current asthma—findings from the child and adult Asthma Call-back Survey. J Asthma. 2015;52(3):318–26. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.956894.

Wheaton A, Cunningham TJ, Ford E, et al. Employment and activity limitations among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-United States, 2013: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015.

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults—United States, 2011.2012 Contract No.: 933–956.

Akinbami L, Xiang L. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;63:1–8.

Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–55. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO.

Yawn BP. Differential assessment and management of asthma vs chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medscape J Med. 2009;11(1):20.

Federman AD, Wolf MS, Sofianou A, et al. Self-management behaviors in older adults with asthma: associations with health literacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):872–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12797.

Brandstetter S, Finger T, Fischer W, et al. Differences in medication adherence are associated with beliefs about medicines in asthma and COPD. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-017-0175-6.

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. COPD | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). 2018.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank and acknowledge the pastors and church representatives for facilitating acceptance of the ACOPD program. We also acknowledge the two departments from the academic institution, Respiratory Therapists from the local health system, students and church members that volunteered for any aspect of the program, and most importantly, all study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Odhiambo, L.A., Anaba, E., Stephens, P.C. et al. Community-Based Approach to Assess Obstructive Respiratory Diseases and Risk in Urban African American Churches. J Immigrant Minority Health 25, 389–397 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01405-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01405-w