Abstract

The quiet ego—a personality construct characterized by empathy, inclusivity, non-defensiveness, and growth-mindedness in self-other relations—correlates positively with varied health markers. There is also emerging evidence that quiet-ego-based interventions may have a positive impact on health-related outcomes. However, no research has examined whether such interventions promote psychological flourishing and through what mechanisms. We addressed this gap with a randomized longitudinal experiment, hypothesizing that a quiet ego contemplation would improve participants’ flourishing and that the link between the intervention and flourishing would be mediated by higher trait emotional intelligence (EI). Using Amazon MTurk, we randomly assigned 75 participants to a 3-session intervention or control condition. As hypothesized, participants in the intervention condition reported higher trait EI scores that, in turn, elevated their flourishing. Results extend the causal benefits of brief quiet ego interventions to psychological flourishing. Given the study’s context during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings may have implications for mitigating the negative impact of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The quiet ego is a personality construct that reflects a self-understanding that transcends egotistical concerns and identifies with a less defensive and growth-oriented stance toward the self and others (Bauer & Wayment, 2008; Wayment & Bauer, 2017). It is less defensive in its identifications (Brown et al., 2008), more authentic in its daily functioning (Kernis & Heppner, 2008), and more inclusive and compassionate in its social relationships (Crocker, 2008). Situated at the theoretical intersection of inclusive identity, perspective taking, detached awareness, and growth mindedness, the quiet ego has been found to be associated with markers of psychological (Wayment & Bauer, 2018; Wayment et al., 2015) and physiological functioning (Collier et al., 2016). In applied, real-world settings, the quiet ego has been linked to adaptive coping in response to extremely adverse events, such as a deadly campus shooting (Wayment & Silver, 2018). The quiet ego has also predicted post-traumatic growth in mothers who raised children with autism spectrum disorder (Wayment et al., 2018a, 2018b), as well as in adults who lost their jobs during the Great Recession (Wayment et al., 2018a, 2018b). It also correlated with enhanced health status in employed and unemployed adults in both the general population (Wayment et al., 2018a, 2018b) and the healthcare context (Wayment et al., 2019).

Given its positive associations with psychological and physiological health markers, recently, researchers began examining its causal relationship with well-being outcomes using experimental methods. Wayment, Collier, et al. (2015) pioneered this line of work by examining the effects of a brief, 3-session quiet ego contemplation training on psychological stress and cognitive performance. The training involved listening to 10-to-15-min audio recordings that explained and contextualized the quiet ego construct as well as participants’ reflection on the connection and applicability of the construct to their life circumstances. Wayment, Collier, et al. (2015) reported that the training effectively attenuated participants’ stress, lowered the extent of their mind-wandering, and improved their performance on a cognitive task. Further, Collier and Wayment (2019) demonstrated that a single-session quiet ego contemplation intervention facilitated the effectiveness of art-making (e.g., expressing one’s experience in a drawing) on enhancing positive and curtailing negative mood. Additionally, Wayment et al. (2019) found that a 4-session, workshop-style quiet ego intervention helped healthcare providers cope with compassion fatigue (i.e., feeling of burnout that leads to a diminished ability to care for patients) and enhanced their overall health, although ecological constraints prevented the study from employing a randomized controlled design.

Together, the correlational and experimental evidence converges on the possibility that the quiet ego is positively associated with another adaptive outcome—psychological flourishing, or a conceptualization of mental health as a constellation of affective well-being, positive social functioning, and psychological fulfillment and not as the mere absence of psychopathology (Keyes, 2005, 2007; WHO, 2004). In fact, the very nature of the quiet ego entails affective (e.g., detached awareness), social (e.g., inclusive identity), and psychological well-being (e.g., growth-mindedness; Bauer & Wayment, 2008; Brown et al., 2008; Crocker, 2008), suggesting conceptually that a quiet ego intervention could elevate and enhance flourishing. However, as the connection between quiet ego and flourishing has rarely been examined in empirical studies, especially in a direct, straightforward manner, it seems important to do so not only to further examine and validate the effectiveness of quiet-ego-based interventions, but also because of the intimate implications of flourishing to people’s emotional and physical health (e.g., cardiovascular disease), daily functioning (e.g., walking or lifting objects), work performance (e.g., lost or cut-short workdays), and healthcare costs and resource utilization (Keyes, 2002, 2005, 2007; Keyes & Grzywacz, 2005; WHO, 2004).

Moreover, it is also important to continue to understand the mechanisms through which quiet-ego-based interventions exert their beneficial influence on health outcomes. As one candidate, trait emotional intelligence (trait EI) refers to one’s subjective evaluation of their capability in handling emotional situations; as a form of emotional self-efficacy, it entails one’s judgment of whether one possesses the necessary resources to deal with prospective emotional situations, most often situations involving other people (Petrides & Furnham, 2006; Petrides et al., 2007). Trait EI is conceptually related to quiet ego in the sense that it is a natural outgrowth of an inclusive psychosocial sphere which is characteristic of quiet ego; in other words, including others in one’s conceptualization of the self necessarily entails the judgment that one is capable of dealing with them and their emotions. This notion was tested and substantiated in a recent study that found that trait EI was positively associated with quiet ego in its mediating role linking quiet ego to subjective well-being (Liu et al., 2020).

Similarly, having favorable perception of one’s capability and effectiveness in handling emotional situations may contribute to one’s overall sense of flourishing, as it not only improves one’s emotional well-being (Nelis et al., 2011), but also one’s social connectedness (Austin et al., 2005; Nelis et al., 2011). This notion is supported by findings from a recent study that indicated that trait EI was positively associated with flourishing and that trait EI mediated the effect of need-for-relatedness on flourishing (Callea et al., 2019). Taken together, theoretical considerations and empirical evidence suggest that trait EI is uniquely positioned to play a mediating role in the connection between quiet ego and flourishing.

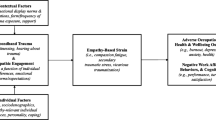

Building on the extant literature, the aim of the present study was to examine, with a randomized experiment, the effectiveness of a quiet-ego-based intervention on psychological flourishing. We hypothesized that the quiet ego intervention would improve quiet ego characteristics and that the increase in quiet ego characteristics would lead to enhanced flourishing. We further hypothesized that trait EI would mediate the effect of improved quiet ego characteristics on flourishing, i.e., a serial mediation from intervention (X) to increased quiet ego characteristics (M1) to higher trait EI (M2) to elevated flourishing (Y). We pre-registered these hypotheses via aspredicted.org. Similar to Wayment, Collier, et al. (2015), we employed a longitudinal design in which the intervention was carried out in three sessions, with each separated by a week (see Fig. 1 for study procedure).

1 Method

1.1 Participants

We pre-registered a sample size of 68; we over-recruited to compensate for participant attrition. Eventually, 75 participants completed this study (via Amazon MTurk) and all their data were retained in the analyses,Footnote 1.Footnote 2 To prevent a ceiling effect and to maximize the likelihood of detecting the intervention’s effectiveness, we targeted participants who scored at or below 3.45 on the Quiet Ego Scale (Wayment et al., 2015; discussed below); this value approximately corresponds to the 34th percentile in the quiet ego score distributions in our prior studies employing MTurk participants (total N = 753).

To minimize the influence of cultural context, we only recruited participants who were raised in the US. Participants averaged 37.96 years in age (SD = 11.43). Fifty-six percent identified as female (N = 42) versus 44% as male (N = 33). Ethnically, the majority (N = 61; 81.3%) identified as Caucasian, 7 (9.3%) identified as Asian, 4 (5.3%) as Hispanic, 2 (2.7%) as Multiracial, and 1 (1.3%) as African American.

2 Materials

2.1 Quiet Ego

The Quiet Ego Scale (QES; Wayment et al., 2015) was used in the initial eligibility survey and the post-training survey to measure the extent to which the four quiet ego characteristics were endorsed by participants: Inclusive Identity, Perspective Taking, Detached Awareness, and Growth-Mindedness. The scale consists of 14 items, assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Sample items include “I rush through activities without being really attentive to them” (Detached Awareness item, reverse-keyed); “When I think about it, I haven’t really improved much as a person over the years” (Growth-Minded item, reverse-keyed); “I feel a connection to people of other races” (Inclusive-Identity item); “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision” (Perspective Taking item). Higher scores (theoretical range of 14–70) indicate greater endorsement of the quiet ego characteristics. The QES’s McDonald’s omegasFootnote 3 for Time 1, Time 4, and Time 5 (Fig. 1) were 0.70, 0.79, and 0.80, respectively.

2.2 Trait EI

Trait EI was measured by the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire—Short Form (TEIQue-SF; Petrides, 2009). The questionnaire consists of 30 items, answered on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Completely Disagree) to 7 (Completely Agree). Sample items include “Many times, I can’t figure out what emotion I'm feeling” (reverse-keyed) and “I’m normally able to ‘get into someone’s shoes’ and experience their emotions.” Scoring is done by first reverse scoring half the items and then averaging across all items, with higher scores (theoretical range of 30–210) indicating greater trait EI. McDonald’s omegas for this scale were 0.92, 0.93, and 0.93 at Time 1, Time 4, and Time 5.

2.3 Flourishing

The Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2007, 2009) was used to measure a sense of flourishing, which is a combination of high levels of affective, social, and psychological well-being. This measure was used because its theoretical basis is more comprehensive, encompassing hedonic, eudaimonic, and social dimensions of flourishing versus other measures (e.g., Diener et al, 2010). The other reason is that this measure has a predefined cut-point for flourishing, which facilitates objective scoring and data analysis. Across 14 items, participants were asked about the frequencies with which they experienced various sentiments and thoughts during the past month on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (Never) to 5 (Everyday). They were asked, for example, how often they felt “interested in life” (affective well-being) or how often they felt that they “had something important to contribute to society” (social well-being). Scoring is done by summing across all items, with higher scores (theoretical range of 0–70) indicating a greater tendency toward experiencing flourishing mental health. The MHC-SF’s McDonald’s omegas for Time 1, Time 4, and Time 5 were 0.94, 0.95, and 0.96 respectively. In addition, we also coded flourishing as a binary categorical variable (i.e., experiencing flourishing or not) according to the instructions in Keyes (2009), as doing so would provide the odds and probability of experiencing flourishing in a logistic regression.

3 Procedure

We randomly assigned participants to either a quiet ego contemplation (QEC) or control condition. Similar to Wayment, Collier, et al. (2015), we designed the training to be completed in 3 sessions, with each separated by a week. And one week after the final session, we invited participants back for a post-training survey. Thus, for each participant, the study duration was 4 weeks in total. Figure 1 illustrates the study procedure.

Prior to the first session, participants were screened for their eligibility for the study. They were invited to complete a survey that hosted only the QES. Participants who scored at or below 3.45, the predetermined cutoff, were then invited back to formally partake in the study sessions. In the first session, participants completed the TEIQue-SF and MHC-SF. Then, participants in the QEC condition went through a 6-min contemplation training in which they listened to an audio recordingFootnote 4 that explained the quiet ego construct as well as elaborated its four characteristics (inclusive identity, perspective taking, detached awareness, growth-mindedness). The recording begins with a definition of the quiet ego as a self-identity that is motivated and able to transcend excessive self-interest. It makes clear that the quiet ego is neither a squashed nor a deflated ego but one that is able to balance self-interest with concerns for others. The recording then delves into the four quiet ego characteristics and illustrates each with detail (see footnote for an example).Footnote 5 After listening, participants answered a few manipulation-check questions to verify that they paid attention to the recording.Footnote 6 Finally, they were instructed to complete a brief reflective writing task on how the four quiet ego characteristics were related to themselves and in what ways the ideas could be applied to their lives.

Participants in the control condition listened to a 6-min audio recording of a chapter from the book In a Wild Place: A Natural History of High Ledges that portrayed natural scenery at High Ledges in Western Massachusetts (Barnard, 1998). The control manipulation—narration of nature scenery—was intended to make participants feel calm, good, and relaxed (which also fit the ostensible title of the study being about relaxation). Both the control and quiet ego recording scripts were narrated by the same person.Footnote 7 After listening, participants completed 5 manipulation-check questions to verify that they paid attention to the recording.Footnote 8

In the second and third (last) training sessions, participants in the QEC condition listened to the same audio recording about quiet ego and then answered manipulation-check questions, after which time they were instructed to complete a brief writing task on the changes they noticed since the previous training and whether they had applied any ideas in the training to their lives. Participants in the control condition, on the other hand, listened to recordings on two other chapters from the same book In a Wild Place: A Natural History of High Ledges and then answered manipulation-check questions (Barnard, 1998).

Finally, in the post-training session, participants from both conditions completed the QES, TEIQue-SF, and MHC-SF. Participants were then debriefed about the purpose of the experiment. Because our data collection coincided with the onset and initial rapid escalation of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US (from mid-February to mid-May, 2020), we added a 1-month follow up to examine whether the quiet ego training resulted in a relatively longer-lasting effect. By the time we received institutional ethics approval, however, about half the participants had already passed the 1-month marker, so we reached out to the remaining participants and eventually managed to retain 42 participants (out of 75). In this session, participants followed the same procedure as in the post-training session in which they completed the QES, TEIQue-SF, and MHC-SF.

4 Study Procedure

4.1 Analytical Strategy

To test our hypothesis that the QEC intervention would enhance quiet ego characteristics, we conducted a regression analysis predicting quiet ego at Time 4 from condition (control condition coded 0 and QEC condition coded 1). To examine the hypothesis that the QEC intervention would improve flourishing at Time 4 and that the effect would be mediated by enhanced quiet ego characteristics at Time 4, we conducted a mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (version 3.5; Model 4) in SPSS, with 10,000 bootstrap re-samples (Hayes, 2018). To further examine the hypothesis that trait EI at Time 4 would mediate the relation between improved quiet ego characteristics and flourishing at Time 4, we conducted a serial mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Model 6) in SPSS, with 10,000 bootstrap re-samples. In addition, we assessed flourishing as both a continuous and categorical measure, as recommended by Keyes (2007) because each approach provides valuable information and can attest whether conclusions vary by approach.

We employed the notational system for the PROCESS macro to describe the path coefficients in the mediation models (Hayes, 2018). For example, a was used to represent paths from the independent or antecedent variable (e.g., QEC intervention) to the mediator variable (e.g., quiet ego score at Time 4); b was used to represent paths from the mediator variable to the dependent or consequent variable (e.g., flourishing at Time 4); and c’ was used to represent paths from the antecedent variable to the consequent variable (i.e., direct effects). In serial mediation models involving two mediator variables, d was used to represent paths from the first mediator variable (e.g., quiet ego score at Time 4) to the second mediator variable (e.g., trait EI at Time 4). We used the notational system in close conjunction with figures when elaborating results to avoid confusion.

There were no missing data in our analyses. We examined assumptions and influential cases of the regression models we ran prior to the main models to check the effectiveness of randomization. We examined assumptions of homoscedasticity, normality, and independent errors with the Breusch-Pagan test (R package “lmtest”), the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the Durbin-Watson test in R Studio. We examined influential cases using Cook’s D, DFbeta values, and studentized residuals and we used the following diagnostic criteria to handle influential cases: They were removed if they exceeded Cook’s D greater than 0.06 (cutoff = 4/n-k-1, Hair et al., 2010), absolute DFbeta values greater than 0.24 (cutoff = 2/√n, Bollen & Jackman, 1990), or absolute studentized residuals larger than 2 (as they are exactly t-distributed, greater than 2 suggests significant outlying values).

5 Results

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the correlations between the study variables, as well as their means and standard deviations for the two conditions. Two points are noteworthy: Trait EI and flourishing at Time 1 correlated highly with their (respective) scores at Time 4 (three weeks later) for both conditions, with the highest correlation being 0.90 between Time 1 and Time 4 trait EI in the training condition. Even at 0.90, however, they are not identical (Fisher z transformed and compared to r = 0.99, z = −4.91, p < 0.001). Next, flourishing correlated highly with trait EI in both conditions. For example, flourishing correlated with trait EI at 0.79 for the control and 0.82 for the training condition at Time 4. This may reflect the fact that both constructs concern people’s subjective and cognitive evaluation of their lives, either in terms of overall functioning (Keyes, 2007) or in terms of their capability to handle prospective emotional situations (Petrides et al., 2007). In addition, certain aspects of the flourishing construct, such as affective well-being or social relationships, may overlap with trait EI as these aspects are inherently concerned with emotional situations.Footnote 9 Empirically, however, the two measures are not identical—A comparison between correlation r = 0.82 with r = 0.99 suggests that they are distinguishable, z = − 6.23, p < 0.001.

6 Randomization Check

Prior to the main analyses, we examined whether randomization was successful. We found no significant differences between participants in the two conditions in their quiet ego, b = 0.04, p = 0.58, trait EI, b = 0.33, p = 0.08, or flourishing scores, b = 3.62, p = 0.29 at Time 1. Participants also did not differ in age, gender, race, social status, and religiosity (all p’s > 0.29), suggesting randomization was effective.

7 Hypothesis Testing

Supporting our hypothesis, the QEC intervention significantly increased participants’ quiet ego scores in the training versus the control condition at Time 4, after accounting for Time 1 quiet ego scores, b = 0.26, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01. The effect amounts to an increase of 0.43 SDs in quiet ego at Time 4 for the training condition (i.e., b = 0.26 divided by Time 4 quiet ego SD = 0.60, Table 2).

We obtained this result after removing three highly influential cases with extreme outlying values that were considerably beyond the cutoffs (Cook’s D = 0.19, 1.6, and 0.25, |DFbetas|= 0.43, 0.75, and 0.36, |studentized residuals|= 3.34, 4.66, and 2.52) that also distorted the normality assumption, W(75) = 0.96, p = 0.01. Their removal restored the assumption, W(72) = 0.98, p = 0.20. Importantly however, the effectiveness of the QEC intervention held up even when these three cases were included in the analysis, b = 0.25, SE = 0.11, p = 0.03.

We then proceeded to the mediation analyses. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that QEC indirectly enhanced participants’ psychological flourishing at Time 4 through its effect on quiet ego at Time 4. As can be seen in Fig. 2, participants in the training condition reported higher quiet ego scores compared to those in the control condition (a = 0.37, p < 0.001), and participants who reported higher quiet ego scores exhibited elevated flourishing (b = 17.33, p < 0.001).

Bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the indirect effect of QEC on flourishing (Time 4) via quiet ego (Time 4), ab = 6.41, Boot SE = 2.70, 95% Boot CI (2.13, 12.62), ab psFootnote 10 = 0.38; participants in the training condition were 0.38 SDs higher on flourishing than participants in the control condition as a result of the effect of QEC on quiet ego that, in turn, elevated flourishing. There was no evidence that QEC influenced flourishing independent of its effect on quiet ego, c’ = 1.42, p = 0.70. We included statistics of the component paths of the mediation model in Table 3.

To analyze flourishing as a binary categorical variable, we ran a mediation analysis with logistic regression. Results revealed that QEC indirectly increased the likelihood of experiencing flourishing at Time 4 through its effect on quiet ego at Time 4. As can be seen in Fig. 3, QEC improved quiet ego characteristics at Time 4 (a = 0.37, p < 0.001), and greater quiet ego characteristics were associated with higher odds of experiencing flourishing at Time 4 (blogit = 2.09, p < 0.01). Bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the indirect effect of QEC on flourishing (Time 4), ablogit = 0.77, Boot SE = 0.66, 95% Boot CI (0.11, 2.48). The indirect effect ab is on a log-odds metric, its equivalent odds ratio and probability are 2.16 and 68%, respectively. That is, the odds of experiencing flourishing for participants in the training condition are 2.16 times higher than those for participants in the control condition. Equivalently, participants are 68% more likely to experience flourishing in the training than in the control condition as a result of QEC’s effect on quiet ego at Time 4 that, in turn, boosted the probability of flourishing at Time 4. There was no evidence that QEC affected flourishing independent of its effect on quiet ego, c’logit = −0.20, p = 0.76. Statistics of the component paths are included in Table 4.

Next, we examined the mediating role of trait EI in two serial mediation analyses. Supporting the hypothesis, we found that trait EI (Time 4) mediated the effect of quiet ego (Time 4) on flourishing (Time 4). As can be seen in Fig. 4, participants in the training condition reported higher quiet ego scores (a1 = 0.37, p < 0.001), who in turn registered greater trait EI scores (d21 = 0.90, p < 0.001), which translated into enhanced flourishing (b2 = 15.06, p < 0.001).

Bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the serial indirect effect of QEC on flourishing (Time 4), a1 x d21 x b2 = 5.04, Boot SE = 2.13, 95% Boot CI (1.63, 9.80), a1 x d21 x b2 ps = 0.30—Participants in the training condition were 0.30 SDs higher on flourishing than those in the control condition as a function of QEC’s effect on quiet ego (Time 4), which in turn raised trait EI (Time 4), which then lifted flourishing (Time 4). There was no evidence that, independent of the serial mediation effect, QEC influenced flourishing (c’ = −2.37, p = 0.36). We included the component paths of the model in Table 5.

We then ran a logistic serial mediation model treating flourishing at Time 4 as a categorical variable. Supporting the hypothesis, we found that QEC enhanced participants’ likelihood of experiencing flourishing (Time 4) via its positive effect on quiet ego (Time 4) which enhanced trait EI (Time 4) that, in turn, increased the likelihood of experiencing flourishing (Fig. 5).

Bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the serial indirect effect, a1 x d21 x b2 logit = 1.17, Boot SE = 10.47, 95% Boot CI (0.38, 4.06). The serial indirect effect is on a log-odds metric; its equivalent odds ratio and probability are 3.22 and 76%, respectively; that is, the odds of experiencing flourishing (Time 4) for participants in the training group are 3.22 times higher than those for participants in the control group. Or participants are 76% more likely to experience flourishing in the training than in the control condition as a result of QEC’s effect on quiet ego (Time 4) that led to an increase in trait EI (Time 4) which then enhanced the probability of flourishing. There was no evidence that QEC affected the likelihood of experiencing flourishing (Time 4) independent of its effects on quiet ego and trait EI at Time 4, c’logit = −1.40, p = 0.13. Statistics of the individual paths are listed in Table 6.

8 Post-Hoc 1 Month Follow-Up

As noted, we contacted a subsample of participants (N = 42) 1 month after they completed the post-training survey to explore whether QEC resulted in any long-lasting effect. We repeated our main analyses with the subsample. We found that participants in the QEC condition registered higher quiet ego scores at the follow-up compared to control participants (Time 5), b = 0.36, SE = 0.17, p = 0.036,Footnote 11 suggesting the QEC intervention generated a stable, longer-lasting positive effect on quiet ego characteristics beyond the initial first week, even during the pandemic.

With respect to the mediation analysis, we ran the same models as in our main analyses, i.e., condition was treated as the independent variable, quiet ego and trait EI at Time 5 as the mediator variables, and flourishing at Time 5 as the dependent variable. We could not run flourishing at Time 5 as a categorical dependent variable as there were only 7 cases that could be categorized as experiencing flourishing according to Keyes (2009), which fails the requirement of having at least 10 cases in the less frequent category of a binary dependent variable for logistic regression (Peduzzi et al., 1996).

We replicated our findings in the main analyses. With respect to the simple mediation analysis, participants in the training condition reported greater quiet ego scores at the follow-up (a = 0.36, p = 0.04) that, in turn, predicted enhanced flourishing at the follow-up (b = 19.40, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Bootstrap confidence intervals with 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the indirect effect from QEC to flourishing, ab = 7.00, Boot SE = 3.89, 95% Boot CI (0.56, 15.91), ab ps = 0.42; that is, participants in the training condition were 0.42 SDs higher in flourishing at Time 5 than those in the control condition as a function of QEC’s effect on quiet ego characteristics (Time 5) that, in turn, elevated flourishing (Time 5). Independent of the indirect effect, there was no evidence that QEC influenced flourishing at the 1-month follow-up, c’ = -2.19, p = 0.61. Statistics of the component paths are included in Table 7.

As to the serial mediation model, we found that QEC resulted in elevated flourishing at the follow-up via quiet ego and trait EI at the follow-up in a serial fashion (Fig. 7). Bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 re-samples were above zero for the serial indirect effect of QEC on flourishing (Time 5), a1 x d21 x b2 = 4.59, Boot SE = 3.14, 95% Boot CI (0.31, 12.54), a1 x d21 x b2 ps = 0.28. There was no evidence that, independent of the serial indirect effect, QEC influenced flourishing (c’ = -3.19, p = 0.34). The statistics of the component paths are summarized in Table 8. Taken together, the mediation and serial mediation results suggest that the intervention generated a stable and visible effect on psychological flourishing that held up for at least 1 month during the COVID-19 pandemic.

9 Discussion

In this randomized controlled experiment, we set out to investigate whether a QEC intervention would (1) improve quiet ego characteristics; and (2) enhance psychological flourishing through quiet ego characteristics and trait EI. We found that, relative to controls, participants in the intervention condition reported higher quiet ego scores, suggesting the QEC intervention effectively improved quiet ego characteristics. And this increase in quiet ego characteristics, in turn, predicted enhanced flourishing. We also found that the process linking improved quiet ego characteristics with elevated flourishing was itself mediated by enhanced trait EI, supporting the proposition that QEC influenced flourishing in a serial fashion via quiet ego characteristics and trait EI.

Our study is the first to directly examine the effectiveness of QEC on flourishing, which complements a series of prior experiments and studies examining the effectiveness of QEC on stress (Wayment, Collier, et al., 2015), on artmaking’s ability to diminish negative mood and amplify positive mood (Collier & Wayment, 2019), and on curtailing compassion fatigue and improving health condition in healthcare providers (Wayment et al., 2019). Our study also improved upon previous studies in various aspects. For example, the study design improves upon Wayment, Collier, et al.’s (2015) by using a control task that was delivered via the same modality; that is, participants listened to control recordings narrated by the same person who narrated the QEC script, whereas control participants in Wayment, Collier, et al. (2015) were instructed to read paper magazines. This not only strengthened the validity of the current results, but also supported the soundness and reliability of prior study results, especially in regard to QEC’s effectiveness in enhancing quiet ego characteristics, which is replicated in the current study (Wayment, Collier, et al., 2015).

Our results align well with prior research (e.g., Liu et al., 2021; Wayment & Bauer, 2018; Wayment Bauer et al., 2015) that suggested an intimate connection between quiet ego and flourishing—the latter being conceptualized as a combination of hedonic (affective), eudaimonic (psychological), and social well-being (Keyes, 2002, 2007). Conceptually and empirically, these two are related. The quiet ego’s concern for long-term growth contributes to eudaimonic well-being, as it clears a space for one to put one’s action (mental and/or behavioral) in a larger, longer-term perspective, facilitating a sense of purpose and meaning over time (Bauer, 2008; Wayment et al., 2015). This long-term orientation, working in tandem with detached awareness, shifts the locus of self-evaluation from the immediate situation (i.e., one’s evaluation of the self is no longer predicated on how the immediate moment makes one feel) to a long-term, process-oriented base, buffering one from processing self-relevant information in overly defensive manners often accompanied by negative affect, tension, and inner conflict, all of which are detrimental to affective well-being (Bauer & Wayment, 2008; Kernis & Heppner, 2008; Leary, 2004). With less egotistical or self-image concerns, the quiet ego is more inclusive in its identification with others and more expansive in its psychosocial sphere that gives rise to more enriching, engaging, and satisfying interpersonal and social relations (Brown et al., 2008; Crocker, 2008; Wayment & Bauer, 2017).

Our results are also consistent with research regarding trait EI, which has revealed a positive association between the quiet ego and trait EI (e.g., Liu et al., 2020). The quiet ego concerns personhood; that is, one’s reflection on what it means to be a person (Wayment et al., 2015). It deals with one’s fundamental conceptualization of one’s self. Trait EI concerns a subset of this conceptualization as it pertains to prospective emotional situations; that is, one’s evaluation of one’s efficacy in handling emotional situations (Petrides et al., 2007). Trait EI is uniquely positioned to be a mediator between quiet ego and flourishing, as it has been shown to predict flourishing in general (Callea et al., 2019) and in the workplace (Schutte & Loi, 2014). Importantly, experimental manipulation of trait EI generated visible effects on two components of flourishing, affective and social well-being (Nelis et al., 2011), thereby supporting the order or flow of effects in the current study (QEC, trait EI, and flourishing).

Notably, our results bear contemporary relevance. The study was conducted between mid-February and mid-May 2020, coinciding with the onset and initial rapid escalation of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US — a public health crisis that profoundly impacted people’s subjective well-being and aggravated their stress levels (O’Connor et al., 2020; Zacher & Rudolph, 2020). Importantly, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that traditional stress appraisal and coping techniques failed to adequately address this negative impact (Zacher & Rudolph, 2020). In light of this, our results not only show promise for increasing flourishing in general, but also for potentially mitigating the negative impact of the pandemic by engaging in a brief QEC training that involved listening to information on the quiet ego’s four components and reflecting about their personal relevance—a readily scalable intervention that anyone can use. This may be especially pertinent to the frontline healthcare workers combating the pandemic to help alleviate their burnout and compassion fatigue (Wayment et al., 2019). Moreover, our follow-up assessment indicated that the benefits of the intervention on flourishing were durable during the protracted pandemic.

This study had several limitations. First, the study population is limited within the US; thus, generalizability of the results to other populations is unknown. Future research will need to replicate the results with more diverse samples, as well as examine the moderating role of sociocultural variables. Second, a concern could be raised that the increase in participants’ QE scores (training condition) was due to teaching-to-the-test, i.e., participants listened to information about the quiet ego and then performed a “test” at the end of the training (Time 4). We do not think this was the case as it could not explain the fact that participants scored similarly high at Time 5, one month after Time 4, during which time they did not listen to information about the quiet ego. And we doubt by then they would remember much about the contents of the training, especially given it was in the depths of the pandemic (May–June, 2020). We also do not think the increase in QE scores could be attributed to social desirability bias as these participants were from the bottom third of the quiet ego score distribution, so their quiet ego scores were already lower than most people’s to begin with; and they were also aware that their individual responses were not going to be analyzed individually and their responses would be aggregated (so that they could not be evaluated negatively). Next, trait EI and flourishing measures correlated highly at Time 4 (0.81). Although the two constructs are distinct theoretically and empirically, their high correlation may be concerning. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution and future research should measure these constructs in diverse ways to replicate and add confidence to the present findings. Further, the initial data collection coincided with the onset and rapid development of the COVID-19 pandemic which might have contributed to participants not responding to study invitation or dropping out of the study midway as life events during the pandemic might have variously impacted their availability and energy and stress levels. Then, the 1-month follow-up study was post-hoc and we lost close to half of our participants by the time we received ethics approval. Yet, this remains an important question and future studies should continue to address the long-term effects of quiet ego interventions. Finally, because we targeted participants whose quiet ego scores were below the 34th percentile to prevent ceiling effect, the QEC’s effectiveness remains unknown for participants at mid or upper ranges; therefore, future testing is needed to establish the reach of the QEC’s effectiveness.

Limitations notwithstanding, we found that a brief cognitive intervention based on quiet ego enhanced participants’ flourishing via its positive effect on quiet ego characteristics and trait EI. This work replicates and extends past research on the effectiveness of quiet ego interventions, as well as on the link between the quiet ego and trait EI; it also lends more empirical support to the relationship between trait EI and flourishing. Finally, the effects may have implications both for improving flourishing in general and in mitigating the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Notes

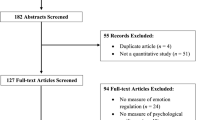

We included in the supplemental material a CONSORT diagram detailing the flow of participants through the study.

The sample size satisfied the requirement for achieving at least .80 power for mediation models using bootstrapping, assuming a medium to large effect size from the independent variable (intervention) to the mediator (trait EI), and from the mediator (trait EI) to the dependent variable (flourishing) (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007, Table 3).

We used McDonald’s omega instead of Cronbach’s alpha as it’s a more accurate reliability index (Dunn et al., 2014; Hayes & Coutts 2020). We used the MBESS package in R to compute the omegas (Kelley, 2007).

The script was obtained by the first author from Dr. Heidi Wayment via email.

Detached awareness “is the ability to restrict or reduce judgment of the self and others, not only in the present moment, but even after the present moment has passed. In this way, detached awareness allows you to more objectively reflect on your past thoughts and feelings, your own strengths and weaknesses. Detached awareness gives you a chance, even if only for a few brief moments at a time, to reduce evaluation and judgment. Detached awareness, in a way, is the ability for you to see “yourself” as if you were observing yourself from outside of your own thoughts and needs. It also is an ability to reflect on how things have gone in the past, and be able to see them objectively, allowing you the possibility to learn from your past actions or inaction.”.

Manipulation check for the training condition consists of two parts — the first part involves 5 statements with a mixture of quiet-ego- and non-quiet-ego-related statements; the assumption is that after listening to the recording, the quiet-ego-related statements (e.g., “listening to the recording helped you remember the importance of review your own actions to learn from them”) should be endorsed more than non-quiet-ego-related statements (e.g., “listening to the recording helped you imagine beautiful places on earth”). The second part is the reflective writing task, the absence or skipping of which constitutes a failure in attention. As pre-registered, failing both parts would result in a rejection and termination of the study.

The person is a native-born Caucasian male who is an academic advisor at a local college in Amherst, Massachusetts, US.

Manipulation check for the control condition consists of 5 multiple-choice questions (on each recording), with each question presenting 4 answer choices. Incorrectly answering more than 2 questions would result in a rejection and termination of the study.

Items in the affective well-being aspect of flourishing (i.e., happy, interested in life, satisfied with life) appeared similar to 2 items from the trait EI questionnaire (30 items in total), namely, “I generally don’t find life enjoyable” (item 5, reverse-keyed) and “On the whole, I’m pleased with my life” (item 20). The item in the social relationships aspect of the flourishing scale — “that you had warm and trusting relationships with others” — resembled 3 items from the trait EI questionnaire, “Those close to me often complain that I don’t treat them right” (item 13, reverse-keyed), “I often find it difficult to show my affection to those close to me” (item 16, reverse-keyed), and “I find it difficult to bond well even with those close to me” (item 28, reverse-keyed).

Partially standardized indirect effect: abps = (ab)/SDY. It expresses indirect effects in terms of the difference in standard deviations in the dependent variable (Y) between two cases that differ by one unit in the independent variable (X) (Hayes, 2018).

All regression assumptions were met. We did not control for Time 1 quiet ego scores (which also did not differ between the two conditions) as (1) the sample was much smaller and much less powered to detect an increase in quiet ego scores from Time 1 to Time 5; (2) our main focus was to see if the QEC intervention would still yield higher quiet ego scores when compared to the control at Time 5.

References

Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., & Egan, V. (2005). Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(3), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.009

Barnard, E. (1998). In a Wild Place: A Natural History of High Ledges. Massachusetts Audubon Society.

Bauer, J. J. (2008). How the ego quiets as it grows: Ego development, growth stories, and eudaimonic personality development. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 199–210). American Psychological Association.

Bauer, J. J., & Wayment, H. A. (2008). The psychology of the quiet ego. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 7–19). American Psychological Association.

Bollen, K. A., & Jackman, R. W. (1990). Chapter 6: Regression diagnostics: An expository treatment of outliers and influential cases. In J. Fox & J. S. Long (Eds.), Modern Methods of Data Analysis. Sage Publications.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., Creswell, J. D., & Niemiec, C. P. (2008). Beyond me: Mindful responses to social threat. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 75–84). American Psychological Association.

Callea, A., De Rosa, D., Ferri, G., Lipari, F., & Costanzi, M. (2019). Are more intelligent people happier? Emotional intelligence as mediator between need for relatedness, happiness and flourishing. Sustainability, 11(4), 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041022

Collier, A. D. F., Wayment, H. A., & Birkett, M. (2016). Impact of making textile handcrafts on mood enhancement and inflammatory immune changes. Art Therapy, 33(4), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1226647

Collier, A. F., & Wayment, H. A. (2019). Enhancing and explaining art-making for mood-repair: The benefits of positive growth-oriented instructions and quiet ego contemplation. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000286

Crocker, J. (2008). From egosystem to ecosystem: Implications for relationships, learning, and well-being. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 63–72). American Psychological Association.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (2nd edn). The Guilford Press.

Kernis, M. H., & Heppner, W. L. (2008). Individual differences in quiet ego functioning: Authenticity, mindfulness, and secure self-esteem. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 85–93). American Psychological Association.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. The American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). Brief Description of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF). https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/MHC-SFEnglish.pdf

Keyes, C. L. M., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2005). Health as a complete state: The added value in work performance and healthcare costs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 47(5), 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000161737.21198.3a

Leary, M. R. (2004). The Curse of the Self: Self-Awareness, Egotism, and the Quality of Human Life. Oxford University Press.

Liu, G., Isbell, L. M., & Leidner, B. (2020). Quiet ego and subjective well-being: The role of emotional intelligence and mindfulness. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00331-8

Liu, G., Isbell, L. M., & Leidner, B. (2021). How does the quiet ego relate to happiness? A path model investigation of the relations between the quiet ego, self-concept clarity, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00438-6

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021554

O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., O’Carroll, R. E., O’Connor, D. B., Platt, S., Scowcroft, E., Watson, B., Zortea, T., Ferguson, E., & Robb, K. A. (2020). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.212

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R., & Feinstein, A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(12), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3

Petrides, K. V. (2009). Psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue). In C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 85–102). Springer.

Petrides, K. V., & Adrian, F. (2006). The role of trait emotional intelligence in a gender-specific model of organizational variables. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(2), 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00019.x

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X120618

Schutte, N. S., & Loi, N. M. (2014). Connections between emotional intelligence and workplace flourishing. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.031

Wayment, H. A., Al-Kire, R., & Brookshire, K. (2018a). Challenged and changed: Quiet ego and posttraumatic growth in mothers raising children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(3), 607–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318763971

Wayment, H. A., & Bauer, J. J. (2017). The quiet ego: Concept, measurement, and well-being. In M. D. Robinson & M. Eid (Eds.), The Happy Mind: Cognitive Contributions to Well-Being (pp. 77–94). Springer International Publishing.

Wayment, H. A., & Bauer, J. J. (2018). The quiet ego: Motives for self-other balance and growth in relation to well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(3), 881–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9848-z

Wayment, H. A., Bauer, J. J., & Sylaska, K. (2015). The quiet ego scale: Measuring the compassionate self-identity. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 999–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9546-z

Wayment, H. A., Huffman, A. H., & Eiler, B. A. (2019). A brief “quiet ego” workplace intervention to reduce compassion fatigue and improve health in hospital healthcare workers. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 49, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.05.002

Wayment, H. A., Huffman, A. H., & Irving, L. H. (2018b). Self-rated health among unemployed adults: The role of quiet ego, self-compassion, and post-traumatic growth. Occupational Health Science, 2(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-018-0023-7

Wayment, H. A., & Silver, R. C. (2018). Grief and solidarity reactions 1 week after an on-campus shooting. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518766431

World Health Organization. (2004). Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice: Summary report. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940

Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2020). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Heidi Wayment for generously sharing an updated version of the quiet ego training script. The authors would like to express gratitude to Dr. Mark Hart for generously donating his time to help record the study scripts.

Funding

This research was supported by a Dissertation Research Grant from the University of Massachusetts Amherst Graduate School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board at UMass Amherst approved this study (protocol number 2019–5855).

Informed consent

Informed consent has been obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Isbell, L.M., Constantino, M.J. et al. Quiet Ego Intervention Enhances Flourishing by Increasing Quiet Ego Characteristics and Trait Emotional Intelligence: A Randomized Experiment. J Happiness Stud 23, 3605–3623 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00560-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00560-z