Abstract

This study examines the relationship between language proficiency and subjective well-being among the first-generation immigrants in Australia. To address endogeneity-related concerns, we use the age at arrival and country of origin as an instrument for English proficiency. Our results show that greater proficiency in English significantly improves self-reported mental health and life satisfaction. These impacts are pronounced among subgroups of males, highly educated individuals, and older immigrants who have lived in Australia for over 30 years. Our mediation analysis suggests that physical health is one of the most important channels through which immigrants’ destination-language acquisition affects their subjective well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data from the HILDA survey are available to approved researchers from government, academic institutions and non-profit organisations.

Notes

Bleakley & Chin (2010) also find that English proficiency plays an important role in immigrant social assimilation.

Given that the major destinations of immigrants are often English-speaking countries, we assume that language proficiency implies skills in English.

Elsner et al. (2018) find that for immigrants, networks that are integrated in the host country lead to better outcomes after migration as well‐integrated networks provide more accurate information on local labour markets.

The information regarding individuals’ English proficiency is provided from 2002.

In Sect. 5, we divide the sample into those who stayed in Australia for 10–30 years and those who stayed for 30–50 years to find out heterogeneous effects.

From the 2002 wave, immigrants were asked: “Do you speak any language other than English at home?” If the response was “Yes,” immigrants were asked: “Would you say you speak English?” Then the answer would be one of the following: “Very well,” “Well,” “Not well,” and “Not at all.”

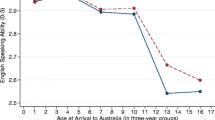

Using this instrument, Bleakley & Chin (2004, 2010) estimate the effect of English proficiency on earnings and social outcomes in the U.S. Clarke & Isphording (2016) and Guven & Islam (2015) investigate the effect of language skills on physical health and social integration of Australian immigrants, respectively.

The educational attainment of immigrants differs depending on immigrant generation and the age at which the immigrant arrives in the host country (Chiswick & DebBurman, 2004; Cortes, 2006; Gonzalez, 2003). Immigrants who arrived before their teen years do not have an earnings deficit relative to observationally equivalent native-born people (Bleakley & Chin, 2004; Chiswick & DebBurman, 2004).

Because of the country of origin and age dummy variables, Eq. (1) can be thought of as a difference-in-differences equation, where the difference in English skills between early and later arrivals from an NES country is compared with the difference in English skills between early and later arrivals from an ES country (Tam & Page, 2016).

Although the IV estimates are higher than the OLS estimates, one must be careful about interpreting these results. As Bleakley & Chin (2004) and Clarke & Isphording (2016) point out, measurement errors in self-reported measures of English language skills can affect OLS and IV results in different directions, in particular when the endogenous variable is an indicator variable. The measurement error could cause OLS estimates to be downward biased, while it might inflate IV estimates in estimating the effect of English skills. Thus, our OLS estimates can be interpreted as a lower bound with regard to the effect of language proficiency on the subjective well-being of Australian immigrants, while the IV estimates provide an upper bound.

The results do not directly show that the estimates by subgroup are significantly different each other.

Two indices are created by using a series of 10 questions in the HILDA self-completed questionnaire. For example: “Do you always feel very lonely?,” “Do you seem to have many friends?,” and “When you are down, do you have someone who always cheers you up?.” Some questionnaires are positive, while others are negative. Therefore, using factor analysis, we create two indices; the one that is mainly loaded with negative questions is called the social isolation index, and the one that is mainly loaded with positive questions is called the social capital index. Both social capital indices are standardized with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Weekly social event is a binary indicator, that is, it equals 1 if a respondent socializes with a friend or family member who does not live with him or her at least once a week.

This is the Sobel-Goodman mediation test.

The weak first stage for a mediator variable could introduce a bias with regard to direct and indirect effects.

References

Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Affairs, 21(2), 60–76

Aleksynska, M., & Tritah, A. (2015). The heterogeneity of immigrants, host countries’ income and productivity: A channel accounting approach. Economic Inquiry, 53(1), 150–72

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Migration, Australia. 2015–16

Bleakley, H., & Chin, A. (2004). Language skills and earnings: Evidence from childhood immigrants. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86, 481–96

Bleakley, H., & Chin, A. (2010). Age at arrival, English proficiency, and social assimilation among US immigrants. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), 165–92

Bloom, D. E., Cafiero, E. T., Jané-Llopis, E., Abrahams-Gessel, S., Bloom, L. R., Fathima, S., et al. (2011). The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Brunner, E. J. (1997). Stress and the biology of inequality. British Medical Journal, 314, 1472–6

Chiswick, B., & DebBurman, N. (2004). Educational attainment: Analysis by immigrant generation. Economics of Education Review, 23, 361–79

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2002). Immigrant earnings: Language skills, linguistic concentrations and the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 31–57

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2003). The complementarity of language and other human capital: Immigrant earnings in Canada. Economics of Education Review, 22, 469–80

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2010). Occupational language requirements and the value of English in the US labor market. Journal of Population Economics, 23, 353–72

Clarke, A., & Isphording, I. E. (2016). Language barriers and immigrant health. Health Economics, 26(6), 765–78

Conti, D. J., & Burton, W. N. (1994). The economic impact of depression in a workplace. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 36(9), 983–8

Cortes, K. E. (2006). The effects of age at arrival and enclave schools on the academic performance of immigrant children. Economics of Education Review, 25, 121–32

Dippel, C., Gold, R., Heblich, S., & Pinto, R. (2019). Mediation analysis in IV settings with a single instrument. Working Paper

Divi, C., Koss, R. G., Schmaltz, S. P., & Loeb, J. M. (2007). Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: A pilot study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(2), 60–7

Dustmann, C., & Fabbri, F. (2003). Language proficiency and labor market performance of immigrants in the UK. Economic Journal, 113(489), 695–717

Dustmann, C., & van Soest, A. (2002). Language and the earnings of immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55(3), 473–92

Elsner, B., Narciso, G., & Thijssen, J. (2018). Migrant networks and the spread of information. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 80(3), 659–88

Evans, G. W., & Kantrowitz, E. (2002). Socioeconomic status and health: The potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annual Review of Public Health, 23, 303–31

Ferrer, A., Green, D. A., & Riddell, W. C. (2006). The effect of literacy on immigrant earnings. Journal of Human Resources, 41(2), 380–410

Fujishiro, K., Xu, J., & Gong, F. (2010). “What does “occupation” represent as an indicator of socioeconomic status?: Exploring occupational prestige and health. Social Science & Medicine, 71(12), 2100–7

Gonzalez, A. (2003). The education and wages of immigrant children: The impact of age at arrival. Economics of Education Review, 22, 203–12

Guven, C., & Islam, A. (2015). Age at migration, language proficiency, and socioeconomic outcomes: Evidence from Australia. Demography, 52, 513–42

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., & Glass, R. (1999). Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1187–93

Kivimäki, M., Lawlor, D. A., Davey Smith, G., Kouvonen, A., Virtanen, M., Elovainio, M., et al. (2007). Socioeconomic position, co-occurrence of behavior-related risk factors, and coronary heart disease: The Finnish public sector study. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 874–9

Lebrun, L. A. (2012). Effects of length of stay and language proficiency on health care experiences among immigrants in Canada and the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1062–72

Remschmidt, H., & Belfer, M. (2005). Mental health care for children and adolescents worldwide: A review. World Psychiatry, 4(3), 147–53

Schachter, A., Kimbro, R. T., & Gorman, B. K. (2012). Language proficiency and health status: Are bilingual immigrants healthier? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(1), 124–45

Schultz, J., O’Brien, A. M., & Tadesse, B. (2008). Social capital and self-rated health: Results from the US 2006 social capital survey of one community. Social Science & Medicine, 67(4), 606–17

Srivastava, P. (2010). Does bingeing affect earnings? Economic Record, 86(275), 578–95

Tam, K. W., & Page, L. (2016). Effects of language proficiency on labour, social and health outcomes of immigrants in Australia. Economic Analysis and Policy, 52, 66–78

Yao, Y., & van Ours, J. C. (2015). Language skills and labor market performance of immigrants in the Netherlands. Labour Economics, 34, 76–85

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the insightful comments made by the Co-editor, Stephanie Rossouw, and two anonymous referees. We also thank Andrew Clarke, Youjin Hahn, Asadul Islam, Robin Sickles, and conference and seminar participants at Asian Meeting of the Econometric Society 2018, International Panel Data Conference 2018, Yonsei University, Monash University, and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology for their helpful comments. Hee-Seung Yang acknowledges the financial support from Yonsei University (Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Program (2021-22-0011)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of us has significant competing financial, professional, or personal interests that might have influenced the work described in this manuscript.

Consent for Publication

The paper is our original work, has not received prior publication, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Niu, A. & Yang, HS. Language Proficiency and Subjective Well-being: Evidence from Immigrants in Australia. J Happiness Stud 23, 1847–1866 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00474-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00474-2