Abstract

This paper discusses the morpho-syntax of phrasal proper names like Deutsche Bahn ‘German Railway’ and Norske Skog ‘Norwegian Forest’ in German and Norwegian. As regards determiner elements, there are three types of phrasal proper names in German: some proper names do not have a definite article, some do, and yet others exhibit a possessive. Depending on the syntactic context, the first two types pattern the same as regards the presence or absence of the article but contrast with the third, where the possessive is always present. It is proposed that proper names in German vary in their structure as regards the presence of the DP-level: unlike articles, possessives have a referential marker, and a DP is obligatorily projected with the latter element. Norwegian is different. While proper names in Norwegian also vary in the presence or absence of determiners, there is no flexibility—determiners are always present or always absent, independent of the syntactic context. It is proposed that unlike in German, the DP-level in Norwegian is always present. As argued by Roehrs (Glossa J Gen Linguist, 5(1):1–38, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1267), phrasal proper names involve a regular syntactic derivation. Given that elements of regular DPs are sensitive to definiteness in Norwegian, it is proposed that Norwegian proper names involve an obligatory definiteness feature. As this feature surfaces in the DP-level, the latter must be present in that language in all instances. Besides this cross-linguistic difference, we document that phrasal PN may show features of recursivity evidenced most clearly in Norwegian.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Proper names (PN) have been of interest to many scholars. Linguistically, PN such as (1a) and (2a) have received a lot of attention (e.g., Longobardi 1994; Matushansky 2008; Muñoz 2019). We will label this type inherent pn. PN such as (1b) and (2b) have not been discussed much (but see Allerton 1987; Roehrs 2020). We will call the latter phrasal pn:

(1) | a. | Peter | (German) | ||

Peter | |||||

‘Peter’ | |||||

b. | Deutsche | Bahn | [company] | ||

German | Railway | ||||

‘German | Railway’ | ||||

(2) | a. | Per | (Norwegian) | ||

Peter | |||||

‘Peter’ | |||||

b. | Norske | Skog | [company] | ||

Norwegian | Forest | ||||

‘Norwegian | Forest’ |

Phrasal PN in German and Norwegian are hybrid elements: semantically, they are referential like inherent PN; unlike inherent PN though, they have descriptive meaning similar to ordinary DPs (Lyons 1999, 21).Footnote 1

Syntactically, PN in German take the shape of ordinary DPs (3a). Indeed, they can be quite complex (3b), which includes syntactically indefinite patterns (3c):

(3) | a. | Die | Neue | Frau | [magazine] | (Ge) | ||

The | New | Woman | ||||||

‘The New Woman’ | ||||||||

b. | Institut | für | Sprach | und | Literaturwissenschaft | [department] | ||

Institute | For | Language | And | Literature.science | ||||

‘Institute for the Study of Language and Literature’ | ||||||||

c. | Ein | Himmel | voller | Betten | [store] | |||

A | Heaven | Full.of | Beds | |||||

‘A Heaven Full of Beds’ | ||||||||

Similar facts hold for Norwegian:

(4) | a. | Den | lille | sjokoladefabrikk-en | [company] | (Nw) | |||

The | Little | Chocolate.factory-def | |||||||

‘The Little Chocolate Factory’ | |||||||||

b. | Institutt | for | lingvistiske | og | nordiske | studier | [department] | ||

Institute | For | Linguistic | And | Nordic | Studies | ||||

‘Institute for Linguistic and Nordic Studies’ | |||||||||

c. | En | Liten | Øl | [company] | |||||

A | Small | Beer | |||||||

‘A Small Beer’ | |||||||||

We will focus on the syntactically definite PN and only briefly discuss syntactically indefinite PN. Thus far, it appears that German and Norwegian pattern the same.

However, as we will lay out in the course of this paper, there are also a number of striking differences. One of the major distinctions between the two languages involves the obligatory presence of determiners in German vs. in Norwegian when phrasal PN occur in argument position:

(5) | a. | *(Die) | Deutsche | Bahn | ist | eine | große | Eisenbahngesellschaft. | (German) | |

the | German | Railway | is | a | big | railway.company | ||||

‘German Railway is a big railway company.’ | ||||||||||

b. | Norske | Skog | er | en | stor | produsent | av | publikasjonspapir . | (Norwegian) | |

Norwegian | Forest | is | a | big | producer | of | publication.paper | |||

‘Norwegian Forest is a big producer of printing paper.’ | ||||||||||

Note that while the phrasal PN in German seems to behave like a typical singular count noun phrase in that it requires the presence of a determiner, its Norwegian counterpart does not. Conversely, when phrasal PN appear in non-argument position such as part of a complex compound, German does not allow an article but Norwegian does:

(6) | a. | der | junge | “(*Der) | SPIEGEL“-Journalist | [magazine] | (Ge) | |

the | young | The | Mirror-journalist | |||||

‘the young Mirror journalist’ | ||||||||

b. | ? den | unge | “Den | Røde | Frakk-en“-ekspeditør-en | [store] | (Nw) | |

the | young | The | Red | Overcoat-def-sales.clerk-def | ||||

‘the young Red Overcoat salesclerk’ | ||||||||

Turning to morphology, it is well known that adjectives in German inflect in accordance with their syntactic context. For instance, if a definite article is present, adjectives have a weak inflection; if there is no determiner, adjectives have a strong inflection. This is often referred to as the strong/weak alternation of adjectives (for background discussion, see Harbert 2007, 134–35 and references cited therein). Interestingly, we find the same with phrasal PN:

(7) | a. | das | Deutsch-e | Historisch-e | Museum | [museum] | (Ge) |

the | German-wk | Historical-wk | Museum | ||||

‘the German Historical Museum’ | |||||||

b. | Deutsch-es | Historisch-es | Museum | ||||

German-st | Historical-st | Museum | |||||

‘German Historical Museum’ | |||||||

As such, phrasal PN in German pattern like ordinary DPs morphologically as well.

Some (other) interesting differences emerge in Norwegian, where weak endings on adjectives are possible, even when a definite determiner is absent. Compare German (8a) to Norwegian (8b). Furthermore, a weak adjective can also be followed by a strong one under certain conditions (8c):

(8) | a. | * Deutsch-e | Historisch-e | Museum | (Ge) | |

German-wk Historical-wk Museum | ||||||

b. | Stor-e | norsk-e | leksikon | [reference book] | (Nw) | |

Big-wk | Norwegian-wk | Encyclopedia | ||||

‘Big Norwegian Encyclopedia’ | ||||||

c. | Ny-e | Norsk-Ø | Tilhengersenter | [company] | ||

New-wk | Norwegian-st | Car.trailer.center | ||||

‘New Norwegian Car Trailer Center’ | ||||||

Besides these syntactic and morphological differences between German and Norwegian, we will illustrate other, related distinctions of these types of phrasal PN. All these differences can be summarized as follows. If a possessive determiner is part of the PN in German, it must be present in all contexts. The definite article fares differently in this language: it must be left out in compound-type structures, in vocatives, or when a demonstrative or possessive is present; it can be left out in certain kinds of listings; and it must be present when the PN occurs in argument positions. In Norwegian, there is no such variation—whatever shape the phrasal PN appears in in the original context, the environment showcasing the official name, its form will not vary in other environments. We will propose for German that phrasal PN with a possessive are frozen at the DP-level. In contrast, phrasal PN with or without a definite article are frozen below the DP-level. As for Norwegian, phrasal PN are invariably frozen at the DP-level. We propose that the latter language involves an obligatory definiteness feature.

In the context of this proposal, other differences involving more complex phrasal PN will be discussed. Both languages allow, with certain qualifications, phrasal PN to be embedded under the adjective for ‘new’ and a few others. This yields a new phrasal PN referring to a different entity. Since the newly formed PN are derived on the basis of other PN, we propose that PN formation is recursive. Again, both languages do not pattern the same here. Unlike neu- ‘new’ in German, nye ‘new’ (with a weak ending) in Norwegian can be followed by a possessive or an adjective with a strong ending, leading to some surface strings that are not possible in regular DPs. We suggest that these unexpected strings indicate different domains within the larger nominal structure. These domains vary cross-linguistically, being a function of the vocabulary elements inside the Lexical Entries. The facts in Norwegian will follow from the proposal that phrasal PN in that language are frozen at the DP-level and that nye forms the head of a functional phrase that selects an existing proprial DP. With German not exhibiting any morpho-syntactic indications of different domains, we propose that the latter language involves a regular but complex nominal.

More generally, we will point out that given that proprial articles can and sometimes must be left out with phrasal PN in German (indicating the absence of the DP-level) and that phrasal PN are clearly recursive in Norwegian (where the higher DP-level involves no referential element), it seems unlikely that referentiality originates in the DP-level.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review some German data that will set the stage for the subsequent comparison with Norwegian. After discussing a recent proposal in Sect. 3, we turn to the discussion of Norwegian in Sect. 4, illustrating certain differences to German. On the basis of these distinctions, Sect. 5 refines the previous proposal. We close the paper in Sect. 6.

2 DP-Level of Phrasal PN in German

Phrasal PN in German exhibit differences in the DP-level. Depending on the syntactic context, we can identify three types of PN in German as regards determiners. In the so-called original context, some PN have no definite article, some do, and yet others have a possessive element. In other non-argument environments, the presence of the definite article varies: the article can be added or left out in list contexts, but it must be absent in compound-type structures and vocatives. We will also see that the definite article can be replaced by a demonstrative or a possessive. Finally, in argument position, determiners are obligatory. After illustrating these points, the different properties of these PN are summarized in Table 1.

Before we start, a brief note on spelling in German is in order (also Nübling et al. 2015, 86ff). With the exception of determiners, prepositions, and particles, the elements of PN are usually capitalized. In fact, sometimes a whole element involves capital letters (e.g., Der SPIEGEL ‘The Mirror’). However, capitalization is not entirely consistent and cannot be used to identify what belongs to a PN (cf. the capitalization of the adjective in (9b) vs. (11b) below). In the gloss, we indicate by capitalization what belongs to the PN. The translation follows the gloss closely. With a few exceptions, this includes capitalization.

2.1 No Determiner in Original Context

We start with the context where complex PN appear in public, that is, on company logos, name signs, etc. Following Roehrs (2020), we will refer to this environment as original context, and we take this string to be the official name. As seen in (9), some PN do not have a determiner:

(9) | a. | stern | [magazine] | (Ge) | |

Star | |||||

‘Star’ | |||||

b. | Neue | Post | [magazine] | ||

New | |||||

‘New Mail’ | |||||

The absence of the determiner seems to be confirmed by contexts where PN occur as part of compounds (10a) (Schlücker 2018).Footnote 2 Furthermore, it is possible to add a definite determiner such as a definite article or, importantly, a demonstrative (10b). Finally, a possessive determiner can also be added (10c):

(10) | a. | der | junge “(*die) | Neue | Post“-Journalist | (German) | ||||

the | young the | New | Mail-journalist | |||||||

‘the young New Mail journalist’ | ||||||||||

b. | Mann, | die / diese | Neue | Post | ist | verdammt | teuer | geworden! | ||

man | the / this | New | is | darn | expensive | become | ||||

‘Boy, the / this New Mail has become darn expensive!’ | ||||||||||

c. | Ach, | meine | Neue | Post | fehlt | mir | aber! | |||

oh, | my | New | misses | me | prt | |||||

‘Oh, I am really missing my New Mail!’ | ||||||||||

2.2 Definite Article in Original Context

There are also some PN that have a definite article in the original context:

(11) | a. | Der | SPIEGEL | [magazine] | (Ge) | |

The | Mirror | |||||

‘The Mirror’ | ||||||

b. | Das | kleine | Weinlokal | [restaurant] | ||

The | Little | Wine.pub | ||||

‘The Little Wine Pub’ | ||||||

Note though that this article must be left out in compound contexts as well (12a). In fact, it can be replaced by a demonstrative (12b) or a possessive determiner (12c):

(12) | a. | der | junge “(*Der) | SPIEGEL“-Journalist | (German) | ||||

the | young | The | Mirror-journalist | ||||||

‘the young Mirror journalist’ | |||||||||

b. | Mann, | dieser | SPIEGEL | ist | verdammt | teuer | geworden! | ||

Man | this | Mirror | is | darn | expensive | become | |||

‘Boy, this Mirror has become darn expensive!’ | |||||||||

c. | Ach, | mein | SPIEGEL | fehlt | mir | aber! | |||

oh, | my | Mirror | misses | me | prt | ||||

‘Oh, I am really missing my Mirror!’ | |||||||||

Observe that with the exception of the original context, this type of PN behaves the same as that discussed in the previous subsection. Specifically, a definite article can be absent in non-argument position (12a), but a determiner including a definite article (see Subsect. 2.4) must be present in argument position (12b,c). In view of these different distributions, we point out already here that the presence of the definite article in German varies according to syntactic context (e.g., non-argument position vs. argument position).

2.3 Possessive in Original Context

There is a third type of phrasal PN that exhibits a possessive, either a possessive determiner or a Saxon Genitive:

(13) | a. | Dein | Telefonladen | [store] | (Ge) |

Your | Phone.store | ||||

‘Your Phone Store’ | |||||

b. | Conny’s | Container | [store] | ||

Conny’s | Container | ||||

‘Conny’s Container’ | |||||

Contexts involving compounds pattern differently here. While perhaps not entirely perfect, the possessive determiner can be present in such contexts (14a). In fact, the possessive determiner cannot be exchanged by a definite article, a demonstrative, or a different possessive (14b) without changing the status of the PN (# indicates the loss of PN status):

(14) | a. | ? | der | junge | “Dein | Telefonladen“-Verkäufer | (German) | ||

the | young | Your | Phone.store-shop.assistant | ||||||

‘the young Your Phone Store shop assistant’ | |||||||||

b. | # | der | / | dieser | / | mein | Telefonladen | ||

the | / | this | / | my | phone.store | ||||

‘the / this / my phone store’ | |||||||||

Note that (14a,b) differ from the two cases discussed above: (14a) has a determiner element present, and (14b) does not allow this determiner to be replaced by another determiner including a different possessive. To be clear, possessive determiner elements in phrasal PN are obligatorily present. To take stock thus far, there are three types of phrasal PN as regards determiners.

2.4 Presence or Absence of the Definite Article in Other Contexts

Besides the original context, there are other non-argument environments PN can occur in. For instance, they can be found in various listings, entries in reference books, etc. In these contexts, the definite article can be added when it is absent in the original context (15a), or it can be left out when it is present in the original context (15b) (also Kolde 1995, 404; Nübling et al. 2015, 81). This yields a syntactically optional article in these types of contexts. In contrast, a possessive cannot be left out without changing the status of the PN (15c):

(15) | a. | (die) | Deutsche | Bank | [bank] | (Ge) | |

the | German | Bank | |||||

‘the German Bank’ | |||||||

b. | (Die) | Neue | Frau | ||||

The | New | Woman | |||||

‘The New Woman’ | |||||||

c. | # | Telefonladen | |||||

phone.store | |||||||

‘phone store’ | |||||||

As far as we have been able to establish, the presence or absence of the definite article in (15a,b) is somewhat random and seems to depend on the individual choice made by the author of the list.

Next, consider vocatives. In this context, a definite article is not possible (16a,b). PN with possessives fare better although they are still a bit marked (16c):

(16) | a. | Hey, | (*die) | Neue | Post, | warum | hast | du | die | Preise | schon | wieder | (Ge) | |

hey | the | New | why | have | you | the | prices | already | again | |||||

erhöht? | ||||||||||||||

increased | ||||||||||||||

‘Hey, New Mail, why have you increased your prices once again?’ | ||||||||||||||

b. | Hey, | (*Der) | SPIEGEL, | warum | hast | du | die | Preise | schon | wieder | erhöht? | |||

hey | The | Mirror | why | have | you | the | prices | already | again | increased | ||||

‘Hey, Mirror, why have you increased your prices once again?’ | ||||||||||||||

c. | ? | Hey, | Dein | Telefonladen, | warum | hast | du | die | Preise | schon | wieder | |||

hey | Your | Phone.store | why | have | you | the | prices | already | again | |||||

erhöht? | ||||||||||||||

increased | ||||||||||||||

‘Hey, Your Phone Store, why have you increased your prices once again?’ | ||||||||||||||

Finally, PN in argument position are different. Here, a determiner element must be present with all types of phrasal PN (also van Langendonck 2007, 18). This is illustrated with a PN that lacks a definite article in the original context:

(17) | a. | *(Die) | Deutsche | Bank | ist | groß. | (German) |

the | German | Bank | is | big | |||

‘The German Bank is big.’ | |||||||

b. | für | *(die) | Deutsche | Bank | |||

for | the | German | Bank | ||||

‘for the German Bank’ | |||||||

The same holds for PN in the plural, which refer to unique sets of elements or events:

(18) | a. | (die) | Schlesische(n) | Kriege | [historical events] | (Ge) | |

the | Silesian | Wars | |||||

‘the Silesian Wars’ | |||||||

b. | # Schlesische | Kriege | waren | grausam. | |||

Silesian | wars | were | cruel | ||||

‘Silesian wars were cruel.’ | |||||||

c. | Die | Schlesischen | Kriege | waren | grausam. | ||

the | Silesian | Wars | were | cruel | |||

‘The Silesian Wars were cruel.’ | |||||||

More generally, the obligatory presence of determiners when phrasal PN occur in argument position in singular or plural contexts means that phrasal PN project (definite) DPs; that is, they are subject to regular syntactic constraints.

Abstracting away from adjectives contained in the phrasal PN, the above discussion is summarized in Table 1 ((+) = already present in the original context; [+] = replacing article from original context).

With the exception of the original context (second column in Table 1), the first two types of PN pattern the same. Although treating these two cases the same may yield a simpler account for German, it will become clear in Sect. 4 that the original context in Norwegian fixes the shape of the PN in the latter language (i.e., PN in Norwegian are ‘frozen’ in appearance). As such, we assume that the original context indicating the presence or absence of the definite article is also important in German. This is in agreement with Payne and Huddleston (2002, 518), who argue that English periodicals have no articles as part of their official names (our original context) but that these names are used with articles in most contexts.

Since the definite article can be left out or be exchanged by another determiner, Roehrs (2020) proposes that this proprial article is an expletive element similar to der in der Peter ‘(the) Peter’ (see Longobardi 1994; Nübling et al. 2015, 123ff). Below, we will follow Roehrs (2020) in making a distinction between the proprial core and the left periphery of phrasal PN.Footnote 3 We will propose that if the definite article does not appear in the orginal context, it is not part of the PN; more precisely, it is not in the Lexical Entry. If the definite article is present in the original context, it is part of the Lexical Entry but not its proprial core (i.e., it has no—what we call for now—referential marker). As such, all definite articles are part of the left periphery of PN. Finally, the possessive is part of the Lexical Entry and the proprial core of the PN. Given this, note already here that the proprial core and the left periphery are not structurally fixed in German—they are relative notions that depend on the type of the determiner present (as we will see below, this is different in Norwegian).

2.5 Some Diagnostics of Phrasal PN

As illustrated above, phrasal PN in German resemble ordinary DPs: morphologically, their inflections vary depending on the context (e.g., the presence or absence of an article; for different morphological cases, see below); syntactically, their appearance differs as regards the presence or absence of the definite article (e.g., when in argument vs. non-argument position) (see also, e.g., Payne and Huddleston 2002, 517; Weber 2004). Schlücker (2018, 282) observes that “[s]peakers encounter new names on a daily basis. This means that only a small percentage of all existing names is known beforehand to language users.” Given these points, we need to provide some diagnostics that justify the distinction between phrasal PN and ordinary DPs.

As already mentioned in the introduction, phrasal PN have some intriguing properties. Allerton (1987, 64–69) provided a brief discussion of some properties of phrasal PN in English. In the context of German, Roehrs (2020) made this discussion more formal and added to it. Some of these points are reviewed below. We focus on the comparison of phrasal PN and definite DPs.

Starting with the semantics, phrasal PN are similar to definite DPs in some respects. As already noted, both have descriptive meaning, they are definite in interpretation, and they are referential. The first characteristic, descriptive meaning, was already discussed and illustrated above. As to the definiteness interpretation, it is well known that definite DPs exhibit a Definiteness Effect in existential there-constructions (19a,b) (Milsark 1974). The same goes for inherent PN (19c) and phrasal PN (20):Footnote 4

(19) | a. | There is a man in the garden. | |

b. | * | There is the man in the garden. | |

c. | * | There is Peter in the garden. | |

(20) | a. | * | There is King’s College in Cambridge. |

b. | * | There is Penny Lane in Liverpool. | |

c. | * | There is Griffy Lake/Lake Monroe in Bloomington. |

Continuing with the third property, both phrasal PN and definite DPs are referential in that the DPs in (21a) and (21b) pick out a referent in the world:

(21) | a. | Das | Deutsche | Historische | Museum | ist | in | Berlin. | (German) | |

the | German | Historical | Museum | is | in | Berlin | ||||

‘The German Historical Museum is in Berlin.’ | ||||||||||

b. | Der | große | braune | Hund | steht | am | Berliner | Rathaus. | ||

the | big | brown | dog | stands | at.the | Berlin | City.hall | |||

‘The big brown dog is standing at the City Hall of Berlin.’ | ||||||||||

However, the conditions that bring about referentiality here are not the same. The phrasal PN in (21a) refers to the same unique entity independent of linguistic context; for instance, the phrasal PN can occur in different situational contexts, and the reference is still the same. In contrast, the reference of the definite DP in (21b) may vary depending on the situational context (Kroeger 2019, 21). Indeed, Lyons (1999, 21–22) makes the distinction between inherently unique definites and contextually unique definites.Footnote 5 In this vein, Kripke (1971) states that proper names are rigid designators; that is, they refer to the same entity in all possible worlds (also Heim and Kratzer 1998, 304; for detailed empirical discussion of inherent PN as regards rigidity and transparent/de re readings, see Longobardi 1994, 637–39).

In his discussion of referentiality, Longobardi (1994) makes a distinction between (inherent) PN and definite DPs. To begin, he argues that referentiality is related to the D-position. He shows that besides PN (and pronouns), common DPs preceded by a definite article can have specific definite interpretations. He proposes that this interpretation is derived in the D-position. Specifically, he argues that raising N to D yields this interpretation and that the proprial article is an expletive element (Longobardi 1994, 648–50, 655). In the appendix of this work, Longobardi suggests that all D-positions are universally generated with the abstract feature [±R(eferential)]. If [+R] is checked, it yields a grammatical derivation involving referentiality. Importantly, only PN (and pronouns) can check this feature, but common definite DPs cannot. Crucially, the D-position, and thus the presence of the DP-layer, is taken to be responsible for referentiality. That the DP-level is related to referentiality appears to be problematic though. This can be seen with certain cases of anaphoric reference, which will also exhibit another difference between PN and common nominals.

It was pointed out above that the definite article must be left out in compound structures (and vocatives) in German. As is clear from anaphoric reference, PN as part of compounds may still refer, but ordinary nouns may not. Specifically, while it is possible to establish coreference in (22a), this is (usually) impossible in (22b) (Haspelmath 2002, 156–60, 2011, 50–51; Schlücker 2018, 290–92; but see also Ward et al. 1991; Alexiadou 2019, who provide instances where the (b)-type of example is possible; LM stands for linking morpheme). Following Ward et al. (1991), we use italics to indicate the anaphoric relation between the antecedent and the pronoun (but remain agnostic here about the nature of this relation):Footnote 6

(22) | a. | Das | ist | die | neue | “SPIEGEL“-Idee. | Er | hat | sie | scharf | verteidigt. | (German) |

this | is | the | new | Mirror-idea | it | has | her | strongly | defended | |||

‘This is the new Mirror idea. It defended it strongly.’ | ||||||||||||

b. | * Das | ist | die | neue | Hund-e-hütte. | Er | hat | sie | nicht | gemocht. | ||

this | is | the | new | dog-lm-hut | he | has | her | not | liked | |||

‘This is the new kennel. He did not like it.’ | ||||||||||||

In other words, phrasal PN do not depend on the presence of the definite article to be referential. As already mentioned, Longobardi (1994) proposes for inherent PN that this element is an expletive article. Above, we sided with Longobardi and assumed that this is also true of phrasal PN. Now, if the obligatory absence of the article coincides with the absence of the DP-level in the compound modifier, then the referentiality of PN is not related to that phrasal layer (but the referentiality of common DPs may well be).Footnote 7

To be clear then, while other elements (e.g., definite DPs) can also be referential, the referentiality of phrasal PN is different. For current purposes, we assume it is inherent with PN, and we will label this semantic property as ‘proprial’ referentiality. Given the above discussion of definiteness, we follow the tradition in the literature (e.g., Payne and Huddleston 2002, 517, 520) and take phrasal PN to be definite in interpretation. Thus, we assume that proprial referentiality entails definiteness.

Turning to the syntactic diagnostics, phrasal PN are frozen. They are fixed as regards morphological number; for instance, if singular, they cannot be pluralized.Footnote 8 Furthermore, restrictive adjectives (but see also below), degree elements, or numerals cannot be added, and elements that are part of the PN cannot be substituted by other elements (e.g., question words). In addition, elements cannot be reordered within the PN, there is no subextraction out of PN, and no elements can be omitted (although the head noun of the PN can be elided).Footnote 9 All these properties have been discussed in detail in Roehrs (2020). Here, we illustrate the frozenness of phrasal PN by the impossibility of adding a degree word (23a) and the impossibility of DP-internal reordering (23b,b’):

(23) | a. | das | (#sehr) | Alte | Testament | [bible] | (Ge) | |||

the | very | Old | Testament | |||||||

‘the Old Testament’ | ||||||||||

b. | Conny’s | Containter | ||||||||

Conny’s | Container | |||||||||

‘Conny’s Container’ | ||||||||||

b.’ | # der | Container | Conny’s | / | von | Conny | / | der | Conny | |

the | container | Conny’s | / | of | Conny | / | the.gen | Conny | ||

‘the container of Conny’s’ | ||||||||||

As to the morphology, we illustrated in the introduction that the strong/weak alternation of adjective endings works the same in phrasal PN as in ordinary DPs. This includes inflections inside phrasal PN (cf. (7a,b)). Furthermore, the proprial article also changes its form according to the syntactic context. Compare (24a) to (24b), where der has been changed to des. Indeed, this may also involve the varying inflection on a noun inside a phrasal PN (24c). Thus, these properties do not differentiate the two types of noun phrases. As far as we know, there is only one (minor) morphological difference between phrasal PN and ordinary DPs that helps distinguish them: ordinary nouns must have a genitive ending (24a) whereas nouns as part of PN may optionally not (24b) (Nübling 2012):Footnote 10

(24) | a. | das | Zerbrechen | des | Spiegel-s | (German) | |

the | shattering | the.gen | mirror-gen | ||||

‘the shattering of the mirror’ | |||||||

b. | die | Berichterstattung | des | SPIEGEL(-s) | |||

the | reporting | The.gen | Mirror-gen | ||||

‘the reporting of the Mirror | |||||||

c. | Jahrestagung | des | Institut-s | für | Deutsche | Sprache | |

annual.convention | the.gen | Institute-gen | For | German | Language | ||

‘annual convention of the Institute for the German Language’ | |||||||

This inflectional difference between (24a) and (24b) is presumably due to the presence of a referential marker on the PN in (24b) (see next section). This tendency toward morphological invariability of PN is often referred to as Schemakonstanz (‘schema constancy’) in the German literature (e.g., Nübling 2017).

Finally, beside the above properties, PN can also be recognized in certain semantic/pragmatic contexts; for instance, it is clear that Conny’s Container in (25a) is not some kind of bin but rather a store. Similarly, Der SPIEGEL in (25b) is not an object in the house but rather a magazine:

(25) | a. | Ich | habe | ein | T-shirt | in | Conny’s | Container | gekauft. | (German) |

I | have | a | t-shirt | in | Conny’s | Container | bought | |||

‘I bought a t-shirt in Conny’s Container.’ | ||||||||||

b. | Sie | hat | den | SPIEGEL | gelesen. | |||||

she | has | The | Mirror | read | ||||||

‘She read the Mirror.’ | ||||||||||

The overall picture that emerges is that while phrasal PN resemble ordinary DPs on the surface, they exhibit some distinguishing properties. Most importantly for current purposes, operations that change the syntactic shape of the proprial string are severely restricted. Roehrs (2020) proposes that phrasal PN are frozen to certain syntactic operations. He proposes that phrasal PN have a derivation similar to that of ordinary DPs. However, further derivational options are constrained by the presence of a referential marker that is part of the Lexical Entries of phrasal PN. This referential marker yields a type of freezing of the PN to certain syntactic operations. In the next section, we will review some of the details of Roehrs’ proposal. This will set up the contrastive discussion of German and Norwegian in the later sections.

3 Previous Proposal

As seen above, phrasal PN have special properties. The following proposal has two parts. In the first subsection, we discuss the acquisition of phrasal PN, which we take to be a one-time memorization procedure yielding complex Lexical Entries. The second subsection addresses the derivations of phrasal PN, which may vary depending on the syntactic context (e.g., argument vs. non-argument position).

3.1 Proprialization and Lexical Entries of Phrasal PN

Roehrs (2020) follows Nübling et al. (2015, 16f) in calling this type of PN formation proprialization. He proposes that the current cases involve a memorization procedure that marks a set of lexical and functional items as being (part of) a proper name. This procedure consists of three steps. First, regular lexical and functional vocabulary elements are taken from the lexicon. Second, these elements receive a referential marker. Finally, Proprialization collects these marked elements in a set and stores this set in the lexicon. To be clear, the formation of a phrasal PN is a one-time procedure bringing about the creation of a Lexical Entry, the result being that the language user has acquired the phrasal PN and has stored it in their lexicon (for more details, see the above-mentioned works).Footnote 11 Consider the resultant Lexical Entries in more detail.

Discussing PN for place names in Dutch such as Amsterdam in (26a), Köhnlein (2015) proposes a tripartite Lexical Entry consisting of a semantic, a syntactic, and a phonological component. Focusing on the first two parts here, he fleshes out the referential marker by positing a referential pointer, a category label, and the feature [+proper].Footnote 12 Specifically, the semantic component involves a referential pointer marked by ↑ and a category label indicated by [+settlement] as in (26b). In the syntax, the elements are marked by the feature [+proper] as in (26b’). The individual components interact with one another indicated by the double arrow below ((26b,b’) is taken from Köhnlein 2015, 201):

Semantically, the postulation of a referential pointer yields the unique reference of a PN, and the category label specifies whether this is a name for a person, a city, a company, etc. Syntactically, the feature [+proper] distinguishes these elements from those of an ordinary DP accounting for certain morpho-syntactic differences between the two.

Discussing differences between compound-type PN in Dutch and phrasal PN in German, Roehrs (2020) extends Köhnlein’s (2015) analysis by proposing that phrasal PN involve a list of unordered, multi-component vocabulary elements. This yields a complex Lexical Entry, a fixed set of vocabulary elements stored in the lexicon. As in Köhnlein, these Lexical Entries have three components: a semantic, a syntactic, and a phonological one.

Let us discuss the three types of phrasal PN from Sect. 2 by starting with (27a). To avoid redundancy, Roehrs assumes that there is only one referential pointer present, and he assigns it to the noun along with the category label (27b). The possessive pronominal is a determiner (27c), and the number specification is a feature taken to be in Num, the head of a NumP (27d). The elements marked by [+proper] form the proprial core, that is, obligatorily present elements, of the PN. Stored sets are indicated by curly brackets. Leaving out the category label, a convenient shorthand for (27b–d) is (27e) ([+p] stands for [+proper]):Footnote 13

The other two types of PN are similar, the main difference being the analysis of the definite article.

Recall that the definite article in Der SPIEGEL ‘The Mirror’ is in the original context (i.e., it is part of the official name) but that it can be left out or be exchanged by another determiner element. Therefore, Roehrs (2020) takes the article to be in the stored set, but it is an expletive as already stated above. As such, the article is not part of the semantic but only of the syntactic and phonological components of the Lexical Entry. Since the article is not obligatorily present in all contexts, he assumes that it does not involve the feature [+proper]. For concreteness, we follow Leu (2015), Roehrs (2013), and references cited therein in taking the article to be a bipartite form consisting of a stem (d-) and an inflection (-er), the latter being determined during the derivation:

The third case, phrasal PN with no article in the original context, is similar to the two previous types. However, here the definite article is absent in all components of the Lexical Entry:

To be clear, Lexical Entries involve fixed sets of multi-component vocabulary elements. The main difference between the entries above is the presence of the determiner element in all three components (possessive), its presence in the syntax and phonology only (definite article is present in the original context), and its absence in all three components (definite article is not present in the original context).

3.2 Derivation of Phrasal PN

After PN are acquired and stored in the lexicon, they can be used. Depending on the syntactic context they appear in, the derivation of the PN may slightly differ. While the derivation of PN with possessives is the same in all contexts, the analyses of PN with or without a definite article vary according to syntactic context. Specifically, although the derivation is based on the vocabulary elements inside the Lexical Entry, certain minor adjustments are made in specific syntactic contexts.

Roehrs (2020) sides with Allerton (1987) in that phrasal PN involve regular nominal strings on the surface only. As discussed in Subsect. 2.5, these strings do not undergo certain syntactic operations (e.g., DP-internal reordering). In other words, phrasal PN are frozen to certain syntactic processes. Roehrs proposes that PN involve derivations like those of ordinary DPs, but with a few additional contraints. Following Chomsky’s (1995) discussion of non-proprial constructions, he assumes that the elements to be used during the derivation are taken from the lexicon and collected in the Numeration. These elements are then Selected from the Numeration and undergo Merge one element at a time. The derivation proceeds bottom-up. Nouns project NPs, and number features project NumPs. Following Cinque (2005, 2010), adjectives are Merged in Spec,AgrP, and determiners surface in the DP-level (for detailed background discussion of the derivation of DPs, see Julien 2005; Alexiadou et al. 2007, and many others).

Phrasal PN are special in two ways: first, the Lexical Entry of the PN serves as (part of) the Numeration; that is, the individual vocabulary elements of the Lexical Entry become (part of) the Numeration. Second, recall that with the exception of the definite article, every item in the Lexical Entry is marked by the feature [+proper]. Roehrs proposes that during the derivation this feature spreads to the hosting phrase of this item. Specifically, this feature projects from the head to its phrase (30a). Norris (2014, 136f) points out that this type of percolation immediately follows from Bare Phrase Structure (Chomsky 1995). Furthermore, with adjectives located in Spec,AgrP, this feature spreads by Spec-head agreement from the specifier to the head of the hosting phrase (30b) (for the discussion of Spec-head agreement, see Chomsky 1986; Gallmann 1996; Alexiadou 2005; Koopman 2006; Baker 2008).Footnote 14 Note that (30a) will yield the fact that the entire phrase containing the specifier will also have that feature:

(30) | a. | X[+p] | -> | XP[+p] | ||

b. | Spec,YP[+p] | -> | Y[+p] | (-> | YP[+p]) |

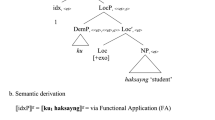

As a consequence, all phrases whose specifier or head have the feature [+proper] will have that feature on the hosting maximal projection as well. This will become relevant below.Footnote 15 Other than that, the derivation proceeds in the way briefly outlined above and illustrated in more detail below. Consider the tree diagram for (31a) in (31b):

(31) | a. Dein | Telefonladen: | {↑telefonladen[+p], dein[+p]; [-pl][+p]} |

Your | Phone.store | ||

| |||

Given a regular structure, we assume that inflections on nouns, adjectives, and determiners are determined during the derivation in the same way as with ordinary DPs. We take it that the minor differences such as the possible absence of the genitive inflection on the proprial head noun (Subsect. 2.5) are due to the presence of the feature [+proper] on that noun.

The derivations of PN with or without a definite article are slightly different. Starting with PN where the article is part of the original context, we proposed in the previous subsection that the article is part of the Lexical Entry but not the proprial core; that is, it is not marked by [+proper]. This is the case with (32a) derived as in (32b):Footnote 16

(32) | a. Der | Spiegel: {↑spiegel[+p], d-; [-pl][+p]} |

The | Mirror | |

|

In the context of vocatives, compound-like elements, demonstratives, and possessives, the article must be deleted (in lists, it may be deleted). Note again that this is an expletive element, and its deletion will not lead to a loss of meaning.Footnote 17

Third, for phrasal PN where the definite article is not in the orginal context, we followed Roehrs in that the article is not part of the Lexical Entry at all. This involves cases like (33a), which are derived as in (33b):

(33) | a. Neue | Post: {↑post[+p], neu[+p]; [-pl][+p]} |

New | ||

|

Unlike above, here a definite article (or other determiners) can be added in certain syntactic contexts. We assume that the relevant determiner is added to the Numeration before the derivation. Specifically, a definite article can be added for list contexts, and a definite article, a demonstrative, or possessive must be added for argument contexts (more on Numerations in later sections). For the latter scenario, we follow Longobardi (1994, 620), who argues that the DP-level is projected for independent reasons when a nominal occurs in argument position (also Stowell 1989). The presence of one of these determiner elements will bring about the DP-level. Note that an added article will be of a definite form because the PN as a whole is referential and thus definite. Consider some consequences of the proposal.

As Longobardi (1994) has demonstrated for Italian, (inherent) PN can undergo certain syntactic operations (e.g., proprial nouns may undergo movement to a location higher than common nouns). Roehrs (2020) proposed that inherent PN are marked by [+proper] as well. This relates inherent PN to phrasal PN directly. This in turn means that the syntactic behavior of phrasal PN can also be taken to be sensitive to the presence of the feature [+proper]. Given that all elements in the syntactic tree are marked by this feature as discussed above, all participate in these syntactic operations equally; that is, no individual element can be singled out. As no element can be affected individually, this yields a type of “freezing” of phrasal PN to certain syntactic operations (Subsect. 2.5). Furthermore, if the feature [+proper] is indeed responsible for this syntactic effect, then it must be present early in the derivation. If it is a marking on a vocabulary element, then vocabulary elements must be inserted early in the derivation (i.e., during syntax), at least with phrasal PN.Footnote 18

We have seen above that the definite article can, and sometimes must, be left out. Note that in either case, the PN can still be referential. As discussed in Subsect. 2.5, it is possible for the hearer to pick out the relevant entity in the world. To repeat from above, if the presence or absence of the definite article correlates with the presence or absence of the DP-level, then the referentiality of phrasal PN does not originate in the DP-level (pace Longobardi 1994). If so, referentiality must come from somewhere else, presumably an element in the lower part of the structure. Roehrs follows Köhnlein (2015) in that it comes from the referential pointer on the noun. This concludes the review of a previous proposal. Next, we turn to Norwegian with the intention of refining the proposal.

4 Phrasal PN in Norwegian

To identify some differences between German and Norwegian, we start this section with some basic data of phrasal PN in Norwegian. In the second subsection, we illustrate that unlike in German, phrasal PN in Norwegian are always frozen at the DP-layer. In Subsect. 4.3, we provide our Lexical Entries and the derivations. In the fourth subsection, we show that phrasal PN in Norwegian exhibit characteristics of recursivity that German does not show as clearly. Finally, we propose that the nominal strings of phrasal PN can be delineated in three different domains that vary cross-linguistically in their structural sizes.

Before we present the data, let us provide a brief statement about the spelling conventions of PN in Norwegian. It is generally recommended to spell only the first word of phrasal PNs with an initial capital letter. However, as our examples will illustrate, there is much variation on this point.

4.1 Basic Data

Like German, Norwegian exhibits both syntactically definite and indefinite DP patterns, the difference being that there is more variation with Norwegian PN, just like with regular DPs (for extensive discussion of the latter, see, for instance, Vangsnes 1999; Julien 2005; Schoorlemmer 2012). Starting with the cases involving syntactic definiteness, there are the well-known DP strings that involve a free-standing and a suffixal determiner (34a). In addition, there is also a distributional pattern identical, on the surface, to generic DPs where the suffixal article is missing (34b):Footnote 19

(34) | a. | Den | Rød-e | Frakk-en | [store] | (Nw) |

The | Red-wk | Overcoat-def | ||||

‘The Red Overcoat’ | ||||||

b. | Den | Gaml-e | Major | [restaurant] | ||

The | Old-wk | Major | ||||

‘The Old Major’ | ||||||

Furthermore, there are phrasal PN that have the patterns involving definite adjectives, sometimes called adjectival determiners. In these cases, the free-standing definite article is missing, but a suffixal determiner may or may not be present. Compare (35a,b):

(35) | a. | Stor-e | Skarv-en | [company] | (Nw) |

Big-wk | Cormorant-def | ||||

‘Big Cormorant’ | |||||

b. | Norsk-e | Skog | [company] | ||

Norwegian-wk | Forest | ||||

‘Norwegian Forest’ | |||||

Turning to the syntactically indefinite patterns, there is the familiar string involving an indefinite article (36a). In addition, there are phrasal PN that are similar to what have been referred to in the literature on Norwegian as type-denoting DPs (Borthen 2003). The latter lack an indefinite article (36b) (note that the adjective liten in (36a) is a portmanteau form and that Ø in (36b) indicates an assumed null ending):

(36) | a. | En | Liten | Butikk | [store] | (Nw) |

A | Small.st | Shop | ||||

‘A Small Shop’ | ||||||

b. | Gul-Ø | Sirkel | [company] | |||

Yellow-st | Circle | |||||

‘Yellow Circle’ | ||||||

Again, all these strings involve well-known patterns. If this is so, then one might expect phrasal PN in Norwegian to contain two adjectives where either both of them exhibit a weak inflection, or both of them show a strong ending. This is indeed the case

(37) | a. | Stor-e | norsk-e | leksikon | [reference book] | (Nw) |

Big-wk | Norwegian-wk | Encyclopedia | ||||

‘Big Norwegian Encyclopedia’ | ||||||

b. | Fin-Ø | Gammel-Ø | Årgang | [company] | ||

Fine-st | Old-st | Vintage | ||||

‘Fine Old Vintage’ |

These are the patterns found in the original contexts in Norwegian. Note that, despite the difference in surface strings, all phrasal PN are referential in the same way; that is, their semantics is independent of their surface shape. With this in mind, we turn to the properties that set phrasal PN in Norwegian apart from those in German.

4.2 Frozen DP-level

In this subsection, we illustrate that phrasal PN in Norwegian can be preceded by demonstratives or possessives (without suppressing the determiner present in the original context). Furthermore, proprial articles in Norwegian are also retained in the context of compound-type structures, vocatives, and list contexts. Finally, Norwegian PN can occur in argument positions without a determiner present. These points are summarized and contrasted with German in Table 2. We will conclude that unlike in German, in Norwegian all phrasal PN are frozen at the DP-level.

Unlike in German, a PN with a free-standing article in Norwegian as in (34a) can be extended by a demonstrative (38a). Similarly, a PN such as in (34b) can take a possessive pronominal on its left (39a). In fact, leaving out the free-standing article of these PN results in degradedness. Consider the two (b)-examples below:

(38) | a. | Wow, | denne | Den | Rød-e | Frakk-en | er | en | flott | butikk! | (Norwegian) |

wow | this | The | Red-wk | Overcoat-def | is | a | great | store | |||

‘Wow, this Red Overcoat is a great store!’ | |||||||||||

b. | ?? Wow, | denne | Rød-e | Frakk-en | er | en | flott | butikk! | |||

wow | this | Red-wk | Overcoat-def | is | a | great | store | ||||

‘Wow, this Red Overcoat is a great store!’ | |||||||||||

(39) | a. | ? Har | dere | besøkt | vår | Den | Gaml-e | Major? | (Norwegian) |

have | you | visited | our | The | Old-wk | Major | |||

‘Have you visited our Old Major?’ | |||||||||

b. | ?? Har | dere | besøkt | vår | Gaml-e | Major? | |||

have | you | visited | our | Old-wk | Major | ||||

‘Have you visited our Old Major?’ | |||||||||

Similarly, adding a demonstrative to (35a) works fine (40a), and the same holds for a possessive pronominal, with (35b) yielding (40b):Footnote 20

(40) | a. | Så, | dette | Stor-e | Skarv-en | et | er | nytt | selskap. | (Norwegian) | |

so | this | Big-wk | Cormorant-def | is | a | new | company | ||||

‘So, this Big Cormorant is a new company.’ | |||||||||||

b. | Vet | du | at | mitt | Norsk-e | Skog | har | hjulpet | meg | mye! | |

know | you | that | my | Norwegian-wk | Forest | has | helped | me | much | ||

‘Do you know that my Norwegian Forest has helped me a lot?’ | |||||||||||

Again, unlike in German, in Norwegian the article can be present in compound-type constructions (41a) and in vocatives (41b):Footnote 21

(41) | a. | ? den | ung-e | “Den | Rød-e | Frakk-en“-ekspeditør-en | (Norwegian) | ||||

the | young- wk | The | Red- wk | Overcoat- def -sales.clerk- def | |||||||

‘the young Red Overcoat salesclerk’ | |||||||||||

b. | Hei, | Den | Rød-e | Frakk-en, | hvorfor | har | du | blitt | så | dyr? | |

hey, | The | Red- wk | Overcoat- def | why | have | you | become | so | expensive | ||

‘Hey, Red Overcoat, why have you become so expensive?’ | |||||||||||

Similarly, the determiner must also be present in list contexts:

(42) | a. | Den | Rød-e | Frakk-en | (Norwegian) |

The | Red-wk | Overcoat-def | |||

‘the Red Overcoat’ | |||||

b. | Den | Gaml-e | Major | ||

The | Old-wk | Major | |||

‘The Old Major’ | |||||

Finally, note that all these Norwegian PN can, as they are, occur in argument position. Illustrating with the type in (36b), where no determiner of any kind is present, the phrasal PN can be the subject or object of a sentence (43a,b). The same goes for the complement position of a preposition (43c):

(43) | a. | Ny-tt | Image | er | min | favorittbutikk. | [company] | (Nw) | ||

New-st | Image | is | my | favorite.shop | ||||||

‘New Image is my favorite shop.’ | ||||||||||

b. | Du | finner | Ny-tt | Image | i | Storgat-a. | ||||

you | find | New-st | Image | in | Big.street-def | |||||

‘You’ll find New Image on Main Street.’ | ||||||||||

c. | På | Ny-tt | Image | får | du | hjelp | med | stil-en. | ||

at | New-st | Image | get | you | help | with | style-def | |||

‘At New Image you get help with your style.’ | ||||||||||

Again, this is different in German. Recall that if a definite article is not present in the original context in the latter language, it must be added when the PN occurs in argument position (Subsect. 2.4). With Longobardi (1994), we assume again that syntactic arguments are DPs. We propose that all phrasal PN in Norwegian involve DPs including the surface strings in (35a,b) and (36b), where free-standing determiners are missing.Footnote 22

To sum up the discussion of Norwegian thus far, demonstrative and possessive pronominals can be added to the left of PN independent of the presence of determiner elements in those PN. Furthermore, PN with determiner elements can occur in compound-type constructions, in vocatives, and lists. Conversely, no (additional) determiner elements are required when PN are in argument position. For convenience, these points in Norwegian are contrasted schematically with German in Table 2 ((+) = already present in the original context; [+] = replacing article from original context; {+} = determiner present if in original context).

Most importantly, unlike in Norwegian, PN in German may leave out an article in non-argument positions (e.g., compounds, vocatives, lists). Conversely, unlike in German, PN in Norwegian may occur without an article in argument positions. We conclude that given the invariable shape of the PN in Norwegian, the latter are frozen at the DP-level. Next, we consider the stored sets of vocabulary elements and the derivations of phrasal PN in Norwegian.

4.3 Lexical Entries and Derivations

In this subsection, we extend the discussion from German to Norwegian. Most importantly, Lexical Entries are formulated in a similar way, the main difference being the obligatory presence of a definiteness feature marked by [+proper] in Norwegian. Furthermore, derivations are the same, with the obligatory definiteness feature in Norwegian always leading to the projection of the DP-level. Indeed, the marking [+proper] on the definiteness feature results in the freezing of the entire DP to certain syntactic operations.

Starting with the cases involving syntactic definiteness, there are many accounts that seek to explain the distribution of the free-standing and the suffixal determiners as well as the weak endings on adjectives in Norwegian. This is not the place to go into a detailed discussion (but see, e.g., Taraldsen 1990; Embick and Noyer 2001; Julien 2005; Anderssen 2006, 2012, and many others). In order to explain the distribution of free-standing and suffixal determiners as well as weak adjective endings, a number of analyses claim that these elements are definiteness-sensitive and are due to the presence of a definiteness feature or several definiteness features (e.g., Julien 2005; Schoorlemmer 2012; Roehrs 2019). As is well known, German does not have suffixal determiners at all. In addition, the endings on adjectives are not regulated by definiteness either (Harbert 2007, 134–35; Roehrs and Julien 2014). As regards the latter point, consider the following nominal strings, which have the same definite interpretation despite the fact that the article is present in the (a)-examples but absent in the (b)-examples. Importantly, while the adjectives in Norwegian are invariably weak here, they vary in German depending on the presence of the article:

(44) | a. | på | den | best-e | måte-n | (Norwegian) |

in | the | best-wk | way-def | |||

‘in the best way’ | ||||||

b. | på | best-e | måte | |||

in | best-wk | way | ||||

‘in the best way’ | ||||||

(45) | a. | das | folgend-e | Beispiel | (German) |

the | following- wk | example | |||

‘the following example’ | |||||

b. | folgend-es | Beispiel | |||

following- st | example | ||||

‘the following example’ | |||||

Thus, unlike in German, the shape of the DP in Norwegian is closely tied to definiteness.

Above, we observed that phrasal PN in Norwegian have different surface patterns: some have determiners, some do not. This means that the frozen DP-level in Norwegian cannot be a function of the presence or absence of determiners. Rather, we propose that what all phrasal PN in Norwegian have in common is the presence of an abstract feature. Given the relevance of definiteness for regular DPs, we take this abstract feature to be a definiteness feature (relating phrasal PN directly to regular DPs). Specifically, we propose for Norwegian that the Lexical Entries for phrasal PN involve a definiteness feature [def] marked by [+proper]. Given the syntactically definite and indefinite strings, we assume that this syntactic feature may have a positive or a negative specification.

One may wonder now why the definiteness feature in Norwegian must be present. Proceeding more tentatively, we pointed out above that, despite the same (referential) semantics, the shape of Norwegian phrasal PN is different. To account for the surface differences, it seems clear that all the relevant vocabulary elements including articles must be present in the Lexical Entries. Notice again that all phrasal PN under discussion here exhibit an overt reflex of (in-)definiteness, articles of various kinds and strong or weak adjectives. To make the discussion concrete, we suggest that all these elements involve an uninterpretable feature for (in-)definiteness. Now, assuming that the aforementioned definiteness feature [±def] involves the interpretable counterpart, its presence in the Lexical Entry and thus in the derivation will allow the uninterpretable feature of the vocabulary elements to be checked resulting in a good derivation.

To sum up, keeping the Lexical Entries as similar to German as possible, there is one substantial difference between the two languages—the presence of the definiteness feature in Norwegian (46a) repeating the example from (34a). Like in German, we take the free-standing article to involve the stem d-; the suffixal article is given here as -e- for concreteness. Note that all the vocabulary elements are marked by [+proper]; that is, they are all part of the proprial core. The Lexical Entry in (46a) can be fleshed out further as in (46b) (u stands for uninterpretable, i indicates interpretable; for Def, see below):

The Lexical Entry for (34b) is given in shorthand in (47a). The other definite instances are similar: (35a) is like (46a) above, and (35b) is like (47a) below, but in each case the free-standing article is not in the stored set. As for the syntactically indefinite cases (36a,b), we assume a definiteness feature with a negative specification (47b,c):

(47) | a. | Den | Gaml-e | Major: |

The | Old-wk | Major | ||

{↑major[+p], gammel[+p], d-[+p]; [-pl][+p], [+def][+p]} | ||||

b. | En | Liten | Butikk: | |

A | Small.st | Shop | ||

{↑butikk[+p], liten[+p], e-[+p]; [-pl][+p], [-def][+p]} | ||||

c. | Gul-Ø | Sirkel: | ||

Yellow-st | Circle | |||

{↑sirkel[+p], gul[+p]; [-pl][+p], [-def][+p]} | ||||

As in German, we claim that the pointer brings about referentiality. (Proprial) referentiality in turn entails semantic definiteness. We assume that the presence of this pointer “overwrites” the negatively specified (syntactic) feature for definiteness in cases like (47b,c). Now, making the standard assumption that the definiteness feature surfaces in the DP-level (Lyons 1999), we can point out that the presence of this feature entails the presence of the DP-level. The feature [+proper] on [def] in the DP-level yields the fact that the DP-level is frozen in Norwegian. With all parts of the tree marked by [+proper], no element can be singled out for certain syntactic operations.

Consider the first steps in the derivation of (34a). Following Taraldsen (1990), Vangsnes (1999), Anderssen (2006, 2012), Julien (2005), and others, we assume that there is a phrase between AgrP and NumP where the definiteness feature [def] originates, call it DefP. With Roehrs (2019), we assume that this feature moves to the DP-level (also Heck et al. 2008, 229; Schoorlemmer 2009):

Before finalizing the derivation, note again that all the elements of the DP in Norwegian have the feature [+proper]. Consequently, the entire DP is frozen.

Continuing the derivation, the copy of [+def] in DP is spelled out by the free-standing determiner (d-), and the copy in DefP by the suffixal one (-e-). These elements were part of the Lexical Entry and thus formed part of the Numeration. The copy of [+def] in Agr will yield a weak adjective ending (for details, see, for instance, Roehrs 2019). The number feature will be spelled out by the relevant number morpheme (in this case, null). Furthermore, the head noun will raise to Num picking up the number morpheme and will then move on to Def supporting the suffixal article. Finally, regular agreement operations and (late) insertion will bring about the relevant inflections:

As is clear from (48b) and (49), there is some DP-internal movement. This means that the feature [+proper] does not block regular movement operations within the DP (but only displacements due to information structure: focus movement, wh-movement, etc.).Footnote 23

More generally, these assumptions explain the difference between German and Norwegian as regards the DP-level. In German, possessives are marked by [+proper] yielding a frozen DP-level; PN with articles, however, are only DPs (necessarily) when they occur in argument position requiring the DP-level to be present for independent reasons; something similar holds for PN without articles. In contrast, Norwegian involves a definiteness feature that is marked by [+proper] thus freezing the DP-level in all cases. With this background in mind, we turn to the facts that are important for the proposal of more complex phrasal PN.

4.4 Recursivity

In Sect. 3, we followed Roehrs (2020) in that phrasal PN involve a regular syntactic derivation. Intriguingly, PN formation is recursive. Norwegian has an element, the adjective nye ‘new’ (and a few others), which can form another PN on the basis of an existing phrasal PN. While German also has this type of element, the properties to be discussed are not as clear there. Besides the differences related to the obligatoriness of the DP-layer, this adds another distinction between the two languages. Note that the following data all lack a determiner in front of the word for ‘new’. In contrast, free-standing determiners are required with regular restrictive modification, a point we will return to at the end of this subsection.

Recall that Norwegian phrasal PN can have two weak adjectives while German cannot (when the definite determiner is absent in the latter language). Consider now (50). What is interesting to observe here is that the Norwegian example in (50a) is ambiguous in interpretation. On the one hand, nye can be part of a regular phrasal PN; in this case, the PN refers to a store that sells new red hats (and presumably some other items). On the other hand, nye can also form a new phrasal PN on the basis of an existing PN (Røde Hatt). In other words, in the first case, a name is given to a store that is established for the first time; in the second scenario, the original store has been remodeled and reopened, or it is possibly under new management in a different location.Footnote 24 We call the first reading of nye primary interpretation (marked below by the superscript 1) and the second reading of nye secondary interpretation (indicated below by the superscript 2). As mentioned above, the German pattern is independently out (50b):

(50) | a. | Ny-e | Rød-e | Hatt | [store] | (√Nw1,2) |

New-wk | Red-wk | Hat | ||||

‘New Red Hat’ | ||||||

b. | * Neu-e | Ägyptisch-e | Museum | (*Ge) | ||

New-wk | Egyptian-wk | Museum | ||||

‘New Egyptian Museum’ | ||||||

We will see that the different readings correlate with some interesting, unexpected morpho-syntactic facts in Norwegian. Specifically, strings with a secondary interpretation allow the adjective nye (with a weak ending) to be followed by an adjective with a strong ending or by a possessive. This is different from German. To the extent that unexpected patterns are possible in the latter language at all, they are quite marked.

Continuing with the different inflectional options, both languages can have two strong adjectives. Here, the adjective for ‘new’ can only have the primary interpretation in Norwegian. In contrast, German allows both readings:

(51) | a. | Ny-Ø | Gul-Ø | Sirkel | [company] | (√Nw1) |

New-st | Yellow-st | Circle | ||||

‘New Yellow Circle’ | ||||||

b. | Neu-es | Ägyptisch-es | Museum | [museum] | (√Ge1,2) | |

New-st | Egyptian-st | Museum | ||||

‘New Egyptian Museum’ | ||||||

Furthermore, the adjective for ‘new’ with a strong ending cannot be followed by an adjective with a weak ending in Norwegian. This combination seems to be marginally possible for some speakers in German:

(52) | a. * | Ny-Ø | Grei-e | Kafeteria | (*Nw) |

New-st | Nice-wk | Cafeteria | |||

‘New Nice Cafeteria’ | |||||

b.% | Neu-es | Ägyptisch-e | Museum | (%Ge) | |

New-st | Egyptian-wk | Museum | |||

‘New Egyptian Museum’ | |||||

Conversely, Norwegian nye can be followed by a strong adjective. In this case, nye only has a secondary interpretation. Note also that this surface string is usually ungrammatical in Norwegian, just as it is impossible in German including with PN:

(53) | a. | Ny-e | Grei-Ø | Kafeteria | [cafeteria] | (√Nw2) |

New-wk | Nice-st | Cafeteria | ||||

‘New Nice Cafeteria’ | ||||||

b. | * Neu-e | Ägyptisch-es | Museum | (*Ge) | ||

New-wk | Egyptian-st | Museum | ||||

‘New Egyptian Museum’ | ||||||

Before we summarize these four inflectionally different patterns, let us point out that there is a related morpho-syntactic difference between Norwegian and German.

While the weak adjective for ‘new’ can be followed by a possessive in Norwegian yielding a secondary interpretation, this is not possible in German. Again, note that this surface string is usually impossible, also in Norwegian:

(54) | a. | Ny-e | Elses | Blomster | [store] | (√Nw2) |

New-wk | Else’s | Flowers | ||||

‘New Else’s Flowers’ | ||||||

b. | * Neu-e | Marias | Laden | [store] | (*Ge) | |

New-wk | Mary’s | Shop | ||||

‘New Mary’s Shop’ | ||||||

If the adjective for ‘new’ has a strong ending in this context, the resultant nominal in Norwegian is out, but the one in German, while quite marked, is not completely impossible:

(55) | a. | * Ny-tt | Elses | Hjem | (*Nw) |

New-st | Else’s | Home | |||

‘New Else’s Home’ | |||||

b. | ?*/?? Neu-er | Marias | Laden | (*Ge) | |

New-st | Mary’s | Shop | |||

‘New Mary’s Shop’ |

Finally, while the most frequent element in this regard appears to be the word for ‘new’, there seem to be a few other adjectives that combine with existing PN yielding newly formed PN:

(56) | a. | Alt-er | Grün-er | Weg | [street name in Alsfeld] | (Ge) | |

Old-st | Green-st | Path | |||||

‘Old Green Path’ | |||||||

b. | Groß-es | Lexikon | der | Astronomie | [reference book] | ||

Big-st | Lexicon | the.gen | Astronomy | ||||

‘Comprehensive Lexicon of Astronomy’ | |||||||

c. | Klein-es | Berlin-Lexikon | [reference book] | ||||

Small-st | Berlin-Lexicon | ||||||

‘Little Berlin Lexicon’ | |||||||

Some Norwegian examples are provided below:

(57) | a. | Gaml-e | Oslo | [a borough in Oslo] | (Nw) |

Old-wk | Oslo | ||||

‘Old Oslo’ | |||||

b. | Lill-e | Frøen | [a neighborhood in Oslo] | ||

little-wk | Frøen | ||||

‘Little Frøen’ | |||||

Note that all these names refer to unique entities that are different from their simpler counterparts, which lack the first element. Thus, these elements are part of the referential component of the PN. More generally, recursivity involving the word for ‘new’ is not an isolated case. However, the elements that can induce recursivity seem to involve a small, restricted set. We continue the discussion with the word for ‘new’.

To sum up thus far, there are some differences between Norwegian and German when the adjective for ‘new’ is followed by another adjective or by a possessive. First, of the four logical inflectional combinations, three are possible in Norwegian with varying interpretative options while German allows only two, one of them being marginally possible for some speakers. Both languages share only one surface string (when both adjectives have a strong ending). Second, when the adjective for ‘new’ has a weak ending, it can be followed by a possessive in Norwegian but not in German. This is summarized in Table 3.

More generally, there are then two unexpected surface strings in Norwegian: the weak adjective nye can be followed (i) by a strong adjective or (ii) by a possessive. These morpho-syntactic patterns correlate with a (necessarily) secondary reading of nye. We take the latter two morpho-syntactic differences to mean that Norwegian nye combines with a lower DP. This fits well with Norwegian phrasal PN being frozen at the DP-level (although the latter is not always overt). Specifically, Norwegian has frozen DPs in isolation as argued in Subsect. 4.2, and we just demonstrated that the very same frozen DPs can occur elsewhere, namely under (secondary) nye yielding recursive patterns. German is different. Assuming that (prenominal) possessives are in the DP-layer, note that German neu- does not combine with a lower DP, but a non-DP is possible; compare (51b), on the secondary interpretation, to (55b).

Before moving on to the next subsection, we would like to point out that the cases discussed above are different from instances involving regular restrictive modification. As pointed out to us by a reviewer, it is indeed possible to distinguish two entities of the same name by adding an intersective adjective such as ‘small’ or ‘big’ (for different types of adjectives, see Kroeger 2019, 275–81). While it is not easy to find authentic examples for phrasal PN, suppose there are two stores or branches with the name Nye Elses Blomster ‘New Else’s Flowers’. In order to differentiate both, one could add a relevant distinguishing adjective, lille ‘small’ in (58a) and store ‘big’ in (58b). Crucially though, a free-standing determiner has to be added to the left periphery as well:

(58) | a. | den | lill-e | Ny-e | Elses | Blomster | (Norwegian) |

the | small-wk | New-wk | Else’s | flowers | |||

‘the small New Else’s Flowers’ | |||||||

b. | den | stor-e | Ny-e | Elses | Blomster | ||

the | big-wk | New-wk | Else’s | flowers | |||

‘the big New Else’s Flowers’ | |||||||

This makes the current cases different from the above instances, which lack a determiner in front of nye.Footnote 25 As mentioned above, Nye Elses Blomster refers to a different store than (unmodified) Elses Blomster, and it is not possible to leave out nye with the first name (even if there is only one such store). Indeed, it is not necessary to add an adjective like ‘old’ to the second name to make the relevant distinction (cf. the inherent PN New York vs. York). In fact, it is possible that although both names are linguistically related, they might offer different goods or services. Finally, PN like Nye Elses Blomster typically, but not necessarily, imply the existence of a different store, namely one with a name that lacks the adjective nye. We conclude that the cases discussed in the first part of this subsection do not involve regular restrictive modification (note also in this regard that we have pointed out above that only a handful of adjectives can be used to create new names highlighting the special status of these cases further).Footnote 26

4.5 Three Domains

In the last subsection, we have shown that phrasal PN are recursive in that Norwegian nye ‘new’ can embed another PN yielding a new one. Interestingly, other elements can appear to the left of that. For instance, the adjective for ‘new’ can be preceded by a non-restrictive adjective and an accompanying determiner (59a). The same holds for German (59b):

(59) | a. | den | berømte | Nye | Elses | Blomster | (√Nw2) |

the | famous | New | Else’s | Flowers | |||

‘the famous New Else’s Flowers’ | |||||||

b. | das | berühmte | Neue | Ägyptische | Museum | (√Ge1,2) | |

the | famous | New | Egyptian | Museum | |||

‘the famous New Egyptian Museum’ | |||||||

We propose that the comparative facts from Norwegian, including the varying interpretative options and the unexpected surface strings, follow from the proposal laid out in Sect. 3 and Subsect. 4.3 once some refinements are made. Specifically, the Norwegian data clearly indicate the presence of different domains with phrasal PN. The combinatory options can be summarized as follows:Footnote 27

(60) | Summary: | |

1. | Phrasal proper names have a frozen primary core. Below, this is marked by curly brackets. | |

2. | Elements can only be added to the left or right. Focusing on the left side for now, there are two types of additions (leading to the embedding of the primary core): | |

a. Creation of a new proper name forming a secondary core (e.g., by adding nye ‘new’ in Norwegian). This is marked by a second set of curly brackets. | ||

b. Construction of a regular left pheriphery (e.g., by adding a definite article and a non-restrictive adjective: Norwegian det/den berømte ‘the famous’). |

Taking the Norwegian example from (59a) above, repeated here as (61a), we illustrate the three domains in (61b). The stored Lexical Entry for a phrasal PN with a secondary core looks as in (61c):

(61) | a. | den | berømte | Nye | Elses | Blomster | (Norwegian) |

the | famous | New | Else’s | Flowers | |||

b. | γ[ regular left periphery | β{ secondary | α{ primary core }α }β ]γ | ||||

c. | Nye Elses Blomster: | ||||||

{↑nye[+p] { blomst[+p], else[+p]; [+pl][+p], [+def][+p]} [+def][+p]} | |||||||

Linearly, the (regular) left periphery precedes the secondary core, and the latter precedes the primary core. Considering (61a,b), nye is, in a way, a linking element between the two other domains (provided the left periphery is present). Note also that the elements in the left periphery are not part of the stored set in (61c). Similar to German PN that lack a definite article in the original context, we suggest that these items are added to the Numeration along with the vocabulary elements from the Lexical Entry of the PN. To be clear then, the Numeration involves the elements from the Lexical Entry, and non-proprial elements such as non-restrictive adjectives and determiners can be added to it as well. The derivation will proceed on the basis of all these elements (for details, see Sect. 5). It will become clear that the domains are a function of the vocabulary elements in the Lexical Entries. With a definiteness feature present in Norwegian but not German, these domains may vary cross-linguistically in terms of their syntax.

It is worth pointing out that other elements can be in the peripheries. As seen in the discussion of German and Norwegian, unstressed, non-restrictive possessives can also be added in the left periphery (the same holds for demonstratives, not shown here):

(62) | a. | Ach, | mein | Peter | (German) |

oh | my | Peter | |||

‘Oh, my Peter’ | |||||

b. | Å, | min | Per | (Norwegian) | |

oh | my | Peter | |||

‘Oh, my Peter’ | |||||

b’. | Å, | Per | min | ||

oh | Peter | my | |||

‘Oh, my Peter’ | |||||

(63) | a. | Ach, | meine | Deutsche | Bank | (German) |

oh | my | German | Bank | |||

‘Oh, my German Bank’ | ||||||

b. | Å, | mitt | Norske | Skog | (Norwegian) | |

oh | my | Norwegian | Forest | |||

‘Oh, my Norwegian Forest’ | ||||||

These possessives establish a close emotional relation to the name and its bearer. Finally, non-restrictive relative clauses also appear in the periphery but on the right.

(64) | a. | die | Deutsche | Bank, | die | übrigens | 1869 | gegründet | wurde |

the | German | Bank | which | incidentally | 1869 | founded | was | ||

‘the German Bank, which by the way was founded in 1869’ | |||||||||

b. | Norske | Skog, | som | forresten | ble | grunnlagt | i | 1962 | |

Norwegian | Forest | which | incidentally | was | founded | in | 1962 | ||

‘Norwegian Forest, which by the way was founded in 1962’ | |||||||||

To take stock, the first point in (60) was derived in Sect. 3 above proposing the operation Proprialization followed by a regular derivation and constrained by the feature [+proper]. The discussion of Norwegian brought to light two differences from German: Phrasal PN in Norwegian are frozen at the DP-level, and they show characteristics of recursivity (not easily seen in German). As discussed in Subsect. 4.3, the first difference followed from the assumption that all stored sets of vocabulary elements in Norwegian involve a definiteness feature marked by [+proper]. The presence of the definiteness feature entails the presence of the DP-level in Norwegian, and the presence of the feature [+proper] explains the fact that the entire DP is frozen. In what follows, we derive the facts involving recursivity and the presence of non-proprial elements in the peripheries by refining the structural assumptions from Sect. 3 and Subsect. 4.3.

5 Domains as Multiple Layers in the Structure