Abstract

Parents of emerging adults are requested to adjust their level of support and control according to their child’s developmental age and to foster their autonomy. This developmental task may be more difficult when emerging adults are suffering from a chronic illness. Parenting emerging adults with a chronic illness is an under-investigated topic, especially with reference to multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic neurological disease usually diagnosed in emerging adulthood. The study aims to qualitatively explore the characteristics of the relationship that parents report having with their emerging adult children (18–29 years) with MS. Specifically, we investigated how the dimensions of support and control emerge from the parents’ perspective, whether overparenting (characterized by both oversupport and overcontrol) emerges, and its characteristics. Eleven semi-structured interviews were conducted with parents of emerging adults with MS, and a qualitative content analysis was performed through Atlas.ti 6.0 software, combining a deductive and an inductive approach in relation to the study aims. A system of 13 codes was defined and a total of 141 quotations were codified. Overparenting appears to be the most frequent relational mode among the parents interviewed. Most quotations referred to oversupport (in particular, parents report anticipatory anxiety about child’s well-being and show excessive indulgence and permissiveness) and overcontrol (in particular, parents report a vicarious management of daily life and medical therapies). The study gives indications for psychological interventions helping parents to adequately support their children while encouraging their autonomous management of daily life and illness-related difficulties.

Highlights

-

Most of the parents interviewed report overparenting their emerging adult children with MS.

-

Oversupport is characterized primarily by parental anticipatory anxiety, excessive permissiveness and infantilization.

-

Overcontrol is characterized primarily by vicarious parental management of both daily life and medical therapies.

-

For some of the parents interviewed, adaptive parenting may coexist with overparenting.

-

Some of the parents interviewed manage to balance support and control, even when relationship difficulties arise due to MS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Emerging Adults and Chronic Illness

Developmental psychology has long emphasized that individual development takes place across the entire lifespan (Baltes, 1997; Elder & Shanahan, 2006; Magnusson & Stattin, 2006) and is promoted by challenges or crisis; when people are successful in facing a challenge and their resources are transformed and increased, development has occurred (Hendry & Kloep, 2002). These challenges are mainly linked to typical and normative developmental tasks of each period of the lifespan (Elder & Shanahan, 2006). For example, the developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (18–29 years of age) are related to gaining independence from parents and making choices about study and future career paths, as well as about committed relationships and parenthood (Arnett, 2000; Arnett et al., 2014; Smorti et al., 2020). Challenges can also be related to non-normative transitions; specifically, the diagnosis of a chronic illness during emerging adulthood is an unexpected event for this period of the lifespan and represents a great challenge for the individual.

Chronic illnesses usually diagnosed in emerging adulthood include multiple sclerosis (MS), a degenerative neurological disease that affects women three times more than men in Italy as in the rest of the world (ATLAS of MS, 2020). Young people diagnosed with MS have to face a double challenge, linked to the developmental tasks typical of emerging adulthood combined with the life-long event represented by illness (Bonino, 2021). Multiple sclerosis is characterized by various symptoms (fatigue, pain, motor and sensory disorders, bladder problems, sexual disturbances, and cognitive impairment) and usually has an unpredictable and fluctuating course with relapses and periods of symptom remission (relapsing–remitting MS [RR-MS]). The main fear of people with MS is that they will suffer a severe motor disability that will force them to use a wheelchair, although this condition only affects a minority of individuals. Like for most chronic illnesses, pharmacological therapies are not resolutive, but they treat attacks and slow down the progression of the disease (Lublin et al., 2014). The presence of multiple and fluctuating symptoms and the unpredictable course have a huge psychological impact on individuals. Although emerging adults diagnosed with MS usually have moderate physical disability (Solari et al., 2008), depressive symptoms, anxiety, and reduced quality of life are generally reported (Buchanan et al., 2010; Rainone et al., 2016). MS can be defined as an unexpected break in the process of identity redefinition (Calandri et al., 2020; Charmaz, 1983) which deeply affects emerging adults’ future life projects. While there are studies on the experience of emerging adults with MS, the parents’ perceptions about an emerging adult child with MS are still largely unexplored.

Parenting Emerging Adults with a Chronic Illness

Development tasks throughout the lifespan concern not only individuals but also the family in which they live. Specifically, the main developmental task of the family with emerging adult children is to promote their need for increasing independence and autonomy and to redefine family relationships (Scabini et al., 2006). Parental support and parental control are the central dimensions of the four parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, neglectful, and indulgent) described by Baumrind (1971, 2012). Support and control are relevant not only during childhood and adolescence, but also during emerging adulthood. They must be developmentally appropriate to promote offspring autonomy and independence (Soenens et al., 2007). On the contrary, parental overprotection and excessive control toward emerging adult children have proved to be related to difficulties in the process of identity definition and autonomy acquisition (Inguglia et al., 2016; Luyckz et al., 2007; Manzeske & Stright, 2009). The construct of overparenting (or helicopter parenting) has been introduced in developmental studies to define a parenting style toward emerging adult children characterized by high support, combined with high parental control and low autonomy-granting (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012; Segrin et al., 2012, 2013). Specifically, overparenting is characterized by a control not consistent with the age of the child, an intrusiveness in the children’s choices, a provision of substantial support (i.e., financial, emotional), and an anticipatory problem-solving which limits emerging adult autonomy (Manzeske & Stright, 2009; Reed et al. 2016; Schiffrin et al., 2014; Winner & Nicholson, 2018). This dependence is especially detrimental in emerging adulthood, when the main developmental task of young people should be to increase independence from parents and reach greater self-reliance (Arnett, 2000). Although the links between overparenting and offspring adjustment are complex, it has proved to have negative consequences on youth development (Miano & Palumbo, 2021; Nelson et al., 2021). Specifically, overparenting was related to decreased self-confidence and maladaptive coping strategies (Givertz & Segrin, 2014; Odenweller et al., 2014), emotion dysregulation (Love et al., 2022), poorer academic functioning (Love et al., 2020; Luebbe et al., 2018), increased depression and anxiety and lower life satisfaction (Cook, 2020; Reed et al., 2016; Schiffrin et al., 2014, 2019).

The challenges faced by the family system with emerging adult children may be increased when they suffer from a chronic illness. According to family systems theory, when illness enters a family, it deeply affects relationships and makes it necessary to redefine family roles according to the illness characteristics and the specific moment of family lifespan (Olson, 2000; Walsh, 2016). The family system is likely to become overprotective when a member experiences illness: family members tend to focus on intrafamily relationships, showing excessive emotional closeness and often limiting the individual space. This greater cohesion might be adaptive to manage the crisis but can have negative consequences in the long term for the process of adjustment to the illness as well as for family well-being (Walsh, 2015). An adaptive family functioning should in fact balance cohesion (i.e., the emotional bonding among family members and the amount of individual autonomy) and flexibility (i.e., the ability of the family to adapt rules to deal with stressors) (Olson, 2000).

Existing studies have largely focused on parenting young children and adolescents diagnosed with various chronic illnesses (the most frequently investigated are type 1 diabetes, cancer, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease), whereas parenting a chronically ill emerging adult is still an under-investigated topic. Overparenting seems to be the normative parenting when having ill children and adolescents (Baudino et al., 2022; Haegele et al., 2022; Hullmann et al., 2010; Trojanowski et al., 2021). It has proved to be related to higher affective well-being among children with chronic illness, but it becomes increasingly negative as children move toward adolescence and emerging adulthood and need increasing autonomy (Gagnon et al., 2020). To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated parenting emerging adults with a chronic illness. The study of Sherman (2015) described overparenting toward people aged 18–30 who were diagnosed with cancer during childhood. Parents showed overprotection, characterized by infantilization and excessive preoccupations, and overcontrol, characterized by intrusiveness, as well as problem-solving, decision-making, and therapies management on the behalf of offspring. Overparenting was related to increased levels of anxiety and depression in children through the mediating effect of ineffective coping strategies (Sherman, 2015). Another study explored the links between parenting and identity among people between the ages of 18 and 25 with type 1 diabetes: emerging adults who reported parental overprotection showed greater difficulties in the process of integrating the illness into their identity. The authors claimed that overinvolved and intrusive parents were likely to decrease offspring self-efficacy in managing illness and this in turn negatively affected the process of identity definition (Raymaekers et al., 2020). Parenting emerging adults with chronic illness seem therefore characterized by the same overprotection and overcontrol identified among some parents of healthy youth and this overparenting has negative consequences for the adjustment to the illness as well.

The Present Study

There is a lack of research on parenting emerging adults with a chronic illness and to our knowledge no previous study has investigated the relationships between parents and emerging adult children diagnosed with MS. This situation is specific and only partially comparable to that described in the above-mentioned studies. The diagnosis of MS during emerging adulthood introduces itself into a normative individual and family history unexpectedly, bringing with it huge change. This is profoundly different from having a disease which started in childhood/adolescence and then experience the transition to emerging adulthood with the illness (Raymaekers et al., 2020; Sherman, 2015). Moreover, MS is not life-threatening, but it is a life-long condition characterized by great unpredictability. The role of parents as caregivers of emerging adults with MS is peculiar: due to the characteristics of MS (multiple symptoms, unpredictable and fluctuating course) parents experience a state of psychological uncertainty and different preoccupations about the future (Calandri et al., 2022; Strickland et al., 2015). These parents should normally adjust their level of involvement and control according to their child’s developmental level and MS adds a further and unexpected challenge. That is why it is crucial to investigate the characteristics of parenting, and whether it involves characteristics of overparenting. This knowledge can have clinical implications for health professionals to support parents who experience difficulties during this developmental transition.

The socio-cultural background of this study refers to the Italian situation, where most emerging adults live with their parents and leave home at around the age of 30, later than in other European countries (EUROSTAT, 2022). In Italy young people finish high school at 19, the average age at graduation is 25, and the entry in the job market is often difficult and temporary, with higher rates of unemployment than in other European countries (STATISTA, 2023). Young people in general postpone adult choices like involving themselves in a committed relationship and having children (Crocetti et al., 2012; ISTAT, 2021). Moreover, family relationships are usually characterized by strong bonding and conservative family values, like in other Mediterranean countries (Carrà et al., 2014). This long transition toward adulthood (Crocetti & Meeus, 2014) and prolonged cohabitation with parents have consequences on family relationships. Specifically, higher levels of overparenting are reported among Italian healthy youth when compared to other countries (Pistella et al., 2022). It is therefore important to deepen our knowledge about parenting emerging adult children with MS in this cultural situation. Interviews with parents make it possible to further explore their perceptions about parenting an emerging adult child with MS and the qualitative analysis makes it possible to gain knowledge on a still under-investigated topic.

To sum up, the present study had the following aims:

-

1.

To explore the characteristics of the relationship that parents report having with their emerging adult children (18–29 years) with MS; in particular, to investigate how the dimensions of support and control emerge from the parents’ perspective.

-

2.

To explore whether situations of overparenting (characterized by both oversupport and overcontrol) emerge and how they manifest themselves.

Method

The COREQ checklist (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) (Tong et al., 2007) was followed to ensure a comprehensive and rigorous report of our qualitative study.

Research Team

The research team consists of SB, emeritus professor, expert in developmental psychology and psychological aspects of MS; EC, Ph.D, associate professor, expert in developmental and family psychology and in qualitative research; MB, psychologist and psychotherapist working in the MS Clinical Center were participants were recruited and trained in qualitative research; FG, psychologist, Ph.D, working at the Psychology Department of the local University and trained in qualitative research.

Participants and Procedure

Parents were recruited at a regional MS clinic center located in a large urban area [blinded for review]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having a child aged 18–29 with a diagnosis of MS; (2) that the child had a mild to moderate level of disability (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] score ≤ 5). The EDSS score (Kurtzke, 1983) is the most widely used measure of disability in MS and is evaluated by a neurologist (range 0–10). Patients scoring <5 are autonomous, ambulatory, sometimes needing rest or aid when walking long distances, with mild neurological deficits that impair full daily activities or require minimal assistance; (3) that the child has not had any cognitive deficit or psychiatric problems. Clinical information was obtained from the patients’ case sheets compiled by the neurologist. Eligible participants were contacted via telephone by a psychologist from the research team (MB) who gave detailed information about the research goals. Of the 17 parents initially contacted, 5 declined to participate due to family or work commitments. After the first interview, slight modifications were made to the wording of the questions, and this pilot interview was not included in the study. Therefore, a group of 11 parents participated in the study and their characteristics are reported in Table 1. There were three couples (mother and father agreed to participate in the study and were interviewed separately). The interviews refer to 8 MS patients (3 females, 5 males), with a mean age of 23 years (SD = 3.1; range 19–28). All emerging adults lived with their parents. All were diagnosed with RR-MS, and the mean disease duration was 3.9 years (SD = 2.9; range 1–10 years). Interview abbreviations for each parent and characteristics of children are reported in Table 2. Parents arranged date, time, and place (Hospital or University) for the interview with the psychologist who conducted the interview (FG and MB). Before the interview, participants were given an anonymous questionnaire to fill in to obtain sociodemographic information and evaluation of some psychological variables for descriptive purposes (Italian validated scales were used and measures are reported in Appendix 1). As for the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), depression scores were under the cut-off for the presence of significant symptoms (<7), whereas anxiety mean scores were between normal (<7) and borderline levels (8–10) indicating the presence of significant anxiety symptoms in some participants. The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol no. 0013772) and all participants gave written informed consent before the interview. No benefit was given to participants for taking part in the research.

The Interview

Semi-structured interviews were based on a predetermined topic guide developed by the entire research team and investigating the following areas: (a) feelings and thoughts experienced when the child was diagnosed with MS and at present; (b) the relationship with the child, difficulties, and strategies in dealing with them; and (c) representation of the future of the child and future plans as a parent. Flexible and open-ended questions allowed participants to introduce topics important to them and made it possible for the interviewer to explore their responses in depth (the interview guide is reported in Appendix 2). Interviews were conducted by two members of the research team (FG and MB). Both psychologists had experience in conducting interviews and were trained in the use of qualitative methodology. They had no relationships with participants prior to the study. Participation of parents in the study was voluntary and independent of whether the children were receiving psychological support in the MS Center. These aspects allowed us to control for potential bias in the research.

During the interview, no one else was present besides the parent and the interviewer. On average, each interview lasted 50 min (range 30–70 min). The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by reconstructing the nonverbal and contextual aspects also thanks to the field notes written by the interviewer. Data saturation was reached after 11 interviews therefore no other participants were recruited. It was not possible to conduct a second meeting with participants to return them the transcripts and to get feedback on the results.

The study was conducted in Italy and interviews were conducted in Italian. The quotes in the article were translated into English by a professional native speaker translator in a process of constant discussion with the research team to verify that the content remained true to the original after translation.

Data Analysis

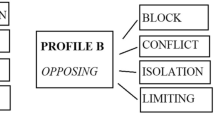

Interview transcripts were considered a single text corpus and underwent qualitative content analysis through Atlas.ti 6.0 software. Content analysis is a research method based on a systematic process of coding textual data (APA, Dictionary of Psychology). In relation to the study aims, a directed approach to content analysis was used (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). According to this approach, theory on parenting practices deductively guided the definition of the initial codes, then new codes were inductively generated starting from the textual material (Mayring, 2014; Schreier, 2014). The analysis was carried out through the following steps: (1) transcripts were read several times by two team researchers (FG and MB) to achieve familiarization with data; (2) following a deductive approach and starting from the theoretical constructs of support and control (Baumrind, 1971, 2012) and overparenting (Segrin, 2012, 2013), four categories were defined after discussion within the research team: balanced support, balanced control, oversupport, and overcontrol; (3) two researchers (FG and MB) independently identified the excerpts that corresponded to these categories and regularly met to discuss the ongoing analysis; (4) starting from elements emerging from the textual material, the initial categorization was refined following an inductive approach with an iterative process involving the entire research team. Three categories (balanced control, oversupport, and overcontrol) were split into subcategories with specific codes to capture more nuanced aspects, and a new category was added (i.e., enmeshment) to codify an aspect that was not anticipated in the initial categories. The final system of 13 codes was discussed and approved by the research team and it is reported in Table 3; (5) after this final procedure, the two researchers then coded all the transcripts independently again. The inter-rater agreement was high (Cohen’s kappa = 0.79; p < 0.001) (Cohen, 1960; McHugh, 2012); (6) discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third judge (EC) until a consensus was reached on each uncertain use of codes.

Results

Results of the qualitative content analysis are summarized in Table 4. Using the code system previously described (13 codes), we codified 141 quotations.

Some parents spoke very little about parenting; in particular, 4 quotations were codified in the interviews P2 and P9, and 5 quotations in the interview P5. On the contrary, other parents addressed this issue to a greater extent; in particular, more than 20 quotations were codified in interviews P8 and P10. Three types of interviews can be identified: (1) interviews where codes referring to adaptive parenting prevail (interviews P1, P2, and P5); (2) interviews where codes referring to adaptive parenting and to overparenting are present in equal measure (interviews P3, P7, and P9); (3) interviews where codes referring to overparenting prevail (interviews P4, P6, P8, P10, and P11). For the sake of clarity, we have reported below results obtained following these three types of interviews, citing some of the most representative quotations.

Adaptive Parenting

The adaptive parenting is based on parental support and proximity appropriate to the child’s age and recognition of their need for autonomy. The following sentences well illustrate these aspects:

The relationship is good…as far as dialogue is concerned; he tells me a lot, and I feel very comfortable with him, … he’s 21…we’ve planted the seeds we needed to plant…you can repeat them to him, remind him about them…but we can’t spend the rest of our lives saying no… (P5)

We’re talking about a person who’s 28, so you need to adjust your behavior in such a way as to not be meddlesome, because she’s got his own life (P2)

Concerning the illness, parents highlight the need to support their children through the difficulties caused by MS and to foster the autonomous management of treatment. Some parents speak of a slow process of change in their relationship with their children, toward more and more respect for their decision-making autonomy. For example, two mothers say:

My biggest preoccupation is to support her as much as I can, so that she doesn’t live/experience these inadequacies the illness gives her as an obstacle to what she can do (P2)

Now I’m pretty calm about it and if he has a relapse, I let him deal with it the way he wants to … if he doesn’t call the doctors, that’s his business, I don’t do it for him …I try to respect his choices now (P1)

These quotations suggest how parents showing an adaptive parenting try to develop a progressive awareness about their child’s situation and implement a gradual distancing. This is a process that takes time and needs to be continually redefined.

Adaptive Parenting and Overparenting

The words of some parents reveal how aspects of adaptive parenting and overparenting are present in equal measure, showing a parental ambivalence. For one mother, the relationship with her daughter is difficult, but the illness led to greater support and proximity. This aspect is acknowledged as positive because it enriched their relationship. She said:

(The relationship) between mother and daughter was difficult before and remained difficult, but not because of the illness … because I’m not saying that the illness got us closer (…) but we did spend a lot of time together, which is maybe something we hadn’t done for a while …. And, from this, we learned to say I love you to each other a bit more (P3)

However, the balance between adequate support and oversupport is very delicate: the parent’s anxiety sometimes leads to oversupport. The parent realizes this and recognizes the need to relax control over the child. The same mother said:

I’ve always been worried about what could happen, then the illness came and at times I can be a bit obsessive…I have this idea that I’ve always got to have everything under control…but I’ve got to start thinking that it won’t always be like that (P3)

These words highlight how important it is for parents to gradually develop awareness of their own attitudes to change them so as not to be intrusive in their relationship with their children.

The ambivalence of some parents is manifested in relation to the dimension of control. A father acknowledges that his son is autonomous in the management of daily life and therapy. However, during the interview, the same father reports controlling behavior toward his son that sometimes leads to conflict. He said:

I’ve got to say he knows how to organize himself … he’s good…when he’s got to study, he doesn’t go out…he always gives himself his little shot in the legs every Sunday evening (P9)

At times I tell him to cover up because it’s cold, to not come home too late …and he always comes home late …you fight over little things (P9)

The links between overcontrol and oversupport also emerge from this father’s words: overcontrol seems to be justified by the need to support the son, but in a way that is not age appropriate. Even the use of the word “little shot”, in addition to minimizing the difficulties related to therapy, seems to be more appropriate for a relationship with a child than with an emerging adult.

Another father recognizes that his child is an adult and therefore an age-appropriate relationship is necessary. He said:

We get on well, but mom and dad always act like they’ve got a child at home, but you’ve got to realize that you’ve got a twenty-five-year-old adult …I’d like to talk to him…but I also don’t want to force these conversations on him, it’s his life, he deserves respect (P7)

In particular, he recognizes that one should not be overprotective and indulgent, for example, by avoiding certain speeches or behavior just because the child is ill.

If I have to tell him off, I don’t think: poor kid! He’s got problems! Because I think that’s the wrong way to go about it, i.e., I don’t want to keep him in a protective bubble (P7)

As mentioned earlier, parents who adopt an adaptive parenting try to avoid attitudes that are not age appropriate because they are dealing with an adult and no longer with a young child. However, the balance between balanced control and overcontrol is very difficult. For example, when it comes to obtaining medical information, aspects of overcontrol in the management of the disease emerge. In particular, the ambivalence emerges when this father justifies his desire to have in-depth information from medical professionals so he can be of help to his son.

my son asks me questions about the therapy, I’ve got to be prepared…I’d like to talk over in private with the neurologist…I get the law on privacy, I understand the need for respect, but we’re not disregarding the need for respect…I’m completely informed about what’s going on with my son and I need to be able to answer his questions (P7)

The examples given thus highlight parents’ awareness of how important it is to implement an age-appropriate parenting for their children, but also how difficult this is when they have a chronic illness.

Overparenting

Overparenting seems to be the most frequent relational mode among the parents interviewed, especially among mothers, and it includes both aspects of oversupport and overcontrol. For a mother, oversupport is mainly manifested through infantilization. She said:

(My son) was diagnosed when he was really young [note: at 16], as a child he was unable to give himself shots. He was afraid of needles, so he was forced to grow up…having to inject the drug into himself every day…his first shots were group shots, i.e., they had to be administered in front of the whole family (P4)

Infantilization is intertwined with vicarious medical management, and it is often facilitated by the need for self-administered medical therapies at home. In the case of hospital therapy, parents are more forced to recognize the need for autonomy, because children relate to other patients and staff. Infantilization seems to be slowly giving way to recognition of greater autonomy on behalf of the child. The same mother quoted above said:

he’s a bit of a sickly child… at first, when he was younger, we always brought him to the hospital to undergo therapy every month, then he got his license and wanted to go on his own (…) I don’t want him to drive after therapy because he comes out of there he’s wiped out, so we worked out a compromise…he goes and eats something and rests, so he lets some time go by, and then he comes back on his own (P4)

For another mother, oversupport is manifested through a strong anticipatory anxiety for her daughter’s well-being and this situation worsened with the disease. She said:

I just can’t be detached … this was probably true even before, then increased with the illness…if she’s got a boyfriend problem, it’s like I were living through it too, that’s my problem (P8)

The illness has led this mother to feeling as if she had an excessive burden to deal with, and the situation worsens every time the daughter must have a routine medical check-up.

what happened was that every time she would call me, a wave of anxiety swept over me, My God! Something’s wrong! So I was in a constant state of incredible anxiety…even now, I feel like I’m much more apprehensive and stressed… I feel like I should do something about it…so, this stuff weighs me down; any time there’s an MRI or a check-up, it’s an ordeal…I start getting worked up six months ahead of time (P8)

During the interview, a strong identification and enmeshment of this mother with her daughter emerges; she goes so far as to say that she herself feels ill and would like to take her daughter’s place even at medical check-ups:

what I feel as a parent…is a bit like I myself were sick…you feel sick too…that is, compared to before, I feel sick…sometimes I say: “I’ll take the MRI in your place” (P8)

In our interviews, excessive anxiety often emerges as an aspect related to oversupport, although only rarely does it reach a lack of distancing and enmeshment.

In an interview with another mother, a relationship with the child based on indulgence emerges. The parent provides too much help to the child because of the illness, tends to justify him for some of his behavior and to concede more than necessary to avoid conflict.

The illness led us to pretty much always let him get his way…we’ve always tried to…give him a bit more than he deserved, we got him a motorcycle, then a car…to help him out as much as possible…which is what I think any parent would do (P10)

When he gets really angry, I’m always afraid it will make things worse…so, maybe to avoid any agitation, you try and pave the way a bit…. (P10)

In this parental couple, the father also acknowledges that he has behaved this way since his son was diagnosed with MS. He said:

It’s probably my fault too, since I’ve been keeping him under a glass dome… he was pretty much always given his way…let’s say it was easier to get things… we didn’t make him responsible in his daily life, even if he’s sick, he takes everything for granted (P11)

Sometimes the child is given goods to help compensate for the difficulties of the illness, without being asked, but to anticipate the solution to problems. This kind of overcontrol emerges from both the mother and the father interviewed:

When he needed an automatic car, we got it for him right away (P10).

He wanted to be self-sufficient at home…to help him out and not see him climb up the stairs, we got a stairlift, but we didn’t tell him… he used it once and then never used it again, he’s sooner drag himself up the stairs… (P11)

These examples well highlight how much overcontrol reflects a self-centeredness of the parent, who does not put himself from the point of view of the sick child.

The overcontrol also emerges as maternal intrusiveness in the son’s daily life management justified with the excuse of needing to take care of him. Specifically, this mother takes care of preparing healthy meals for the child and does household chores for him. She said:

For almost a year now, every day for lunch I’ve been preparing home-grown vegetables for him, eggs from our own hens, and get milk from the farm because, if we do everything we can to keep his organism healthy, the medicine does a bit less damage. Now I also pay someone to come clean and iron for him (P10)

This type of relationship risks having negative psychological effects both on the child and on family dynamics. This mother’s words induce guilt in the child for what the parent does “for his own good” and the risk of conflictual situations arising in the family is reported.

because he’s got to realize that the sacrifices we’ve made over the years have been for his own good, not out of meanness (P10)

I’ve been paying for his groceries, but his brother pays for all his own expenses and rightfully so, points out that he shouldn’t be handed everything on a silver platter just because he’s sick (P10)

In an interview with another mother, the aspects of overcontrol over decisions concerning work and illness disclosure emerge. According to the mother, the son should communicate the illness to the future employer to have work benefits and submit the documents to obtain a disability certificate, while the son disagrees. She said:

Arguments always come up when we talk about work because I tell him that when he goes to work (…) he has to tell them he has multiple sclerosis because they ask for health records and a bunch of things (…) because it’s right that they know, because he needs treatment, personal days, etc… (P6)

We’re insisting that he …fill out the forms…for disability…he’s got to understand that if he doesn’t fill out the application for invalidity…maybe so he can be put on some special list …he’s going to find it really tough, that’ what I’m afraid of… (P6)

These examples also highlight parents’ inability to put themselves from their child’s point of view; this self-centeredness in our interviews is often accompanied by overcontrol.

During the interview, aspects of overcontrol over decisions concerning the illness also emerge; in particular, this mother feels that her son should face and compare himself with other young people with multiple sclerosis, for example within psychological support groups.

For example, I wouldn’t mind if he went some meetings once in a while to talk with other kids …his doctor should be the one to tell him to go to a psychologist…that way he might think about doing it (P6)

What emerges from this mother’s words is her difficulty to respect her son’s decisions (e.g., regarding the disclosure of the illness) and the impact this has on the family relationship in terms of dialogue and conflict.

he doesn’t want us to talk [about the illness], I’d like to talk about it, I wouldn’t have any problem with it, in fact, it would be liberating for me…. he doesn’t want to talk about it, I respect that, [even if] I can’t understand why …he says he doesn’t want any pity (P6)

However, this mother acknowledges in the interview that changes have occurred over time. She said:

We talk about it a bit more than we did at first, when it was absolutely tabu, we couldn’t bring it up because he’d leave, slamming the door, it was really difficult for the family to deal with (…) now life is a bit calmer, more composed, more serene than before (P6).

The latter example shows well how parents have to go through a long, slow journey of accepting the child’s wishes, in which the parent tries to provide adequate support and implement an adaptive relationship.

Discussion

The present study examined parental perceptions of their relationship with an emerging adult child diagnosed with MS. In particular, the interviews with parents explored dimensions of parental support and control and the presence of overparenting practices characterized by both oversupport and overcontrol. From the interviews with parents, it appears that support and control are core elements of their relationship with their adult children and are closely intertwined. This is consistent with the developmental psychology literature, which suggests that both support and control shape parenting from infancy through emerging adulthood (Baumrind, 1971, 2012; Soenens et al., 2007). These two dimensions must be developmentally appropriate to promote children’s autonomy and independence, and this is particularly important in parenting emerging adult children, whose most important developmental task is to acquire independence from the family (Arnett, 2000; Scabini et al., 2006). The diagnosis of a chronic illness such as MS presents an additional challenge to the family system, which is already engaged in this redefinition of family relationships. Our findings suggest that parents respond differently in the face of this challenge: some practice adaptive parenting with balanced support and control, others are ambivalent, and adaptive parenting practices appear to coexist with overparenting, yet others exhibit overparenting practices characterized by both oversupport and overcontrol.

Parents who succeed in balancing support and control often report that they have always tried to implement these parenting practices, even as their children grew and moved toward adulthood. These parents have tried to maintain and adapt these practices, even in the face of changes brought on by the illness. For some parents, supportive relationships within the family have deepened since diagnosis, and affective closeness goes hand in hand with respect for children’s autonomy in managing care and making decisions in a process of change that is not easy and is still ongoing. The individual and contextual resources of these parents are likely to enable them to successfully manage the challenge of the relationship with an emerging adult child with a chronic illness and transform it into an opportunity for development (Hendry & Kloep, 2002).

Other interviews suggest that the boundaries between adaptive parenting and overparenting are blurred. Some parents appear to oscillate between adaptive parenting and overparenting, reflecting ambivalence and difficulties in maintaining developmentally appropriate control and support. In particular, some interviews suggest that affective closeness risks turning into overprotection in the presence of excessive parental anxiety. This finding is consistent with studies showing that high levels of parental anxiety are often associated with overparenting (Gagnon & Garst, 2019; Jiao & Segrin, 2022; Segrin et al., 2013). The presence of significant anxiety symptoms in the parents in our sample is also confirmed by the scores reported on the anxiety self-assessment questionnaire. Similarly, the need to provide effective support to children sometimes leads parents to justify the need to control them in daily life as well as in coping with illness in ways that are developmentally inappropriate. This finding has been found in the literature on overparenting toward healthy emerging adults (Schiffrin et al., 2014; Winner & Nicholson, 2018) and also appears to apply to the relationship between parents and emerging adult children with MS. The coexistence of adaptive and non-adaptive parenting practices underscores that the process of adaptation to chronic illness is complex and continuous for the family system (Calandri et al., 2022, 2022; de Ceuninck van Capelle et al., 2016; Messmer Uccelli, 2014).

Most of the parents interviewed reported overparenting practices that are indicative of the difficulties brought on by the illness, which disturbs the often already delicate balance in the relationship between parents and children. Oversupport and overcontrol are closely related and often originate in parental anticipatory anxiety about their child’s health. Parental anxiety is mainly due to the uncertainty of MS and causes some parents to overprotect their emerging adult children by overindulging or infantilizing them. Previous studies have shown that both indulgence and infantilization, even when well-intentioned and motivated by concern for children’s health, do not promote children’s decision-making autonomy and return them to a state of dependence on their parents (Raymaekers et al., 2020; Sherman, 2015). Our findings shed light on the specificity of this situation when parenting an emerging adult with MS.

Indulgent parents show excessive tolerance or find solutions to their children’s daily or work problems or offer solutions to cope with illness difficulties. Through indulgence, parents often do not put themselves in the child’s shoes and propose solutions that are not desired and ultimately not accepted. As described in the literature, parental indulgence can reinforce the child’s perception of being ill and the belief that he or she cannot cope with difficult situations independently but must rely on others for help (Sherman, 2015).

Other parents show infantilization of their children; they treat them as if they were younger and believe they need their help, reverting to a situation of parental care when they were a child. Infantilization is common when children’s illnesses begin in childhood and parents continue to assume a caring role even when children are adults and they are expected to gradually learn to self-manage their chronic illness (Lerch & Thrane, 2019; Sherman, 2015). The situation is different for MS because the disease has a sudden onset in emerging adulthood. This transition may result in parents reassuming a caring role, altering a parent–child relationship that may have already been redefined in terms of increasing independence. Although emerging adults with MS may need adequate psychological support from parents to cope with the illness, most do not have debilitating physical disabilities that require parental assistance. Therefore, excessive parental care is often motivated not by an actual need of the children but by anticipation of future difficulties due to the unpredictability and fluctuating course of MS. This creates a vicious cycle that reinforces parental anxiety.

Overprotective parents tend to be overly controlling of their children, especially through vicarious management of their daily lives and medical treatments. Parental intrusiveness may manifest itself not only through behavioral control (e.g., preparing meals for the children, participating in medical examinations) but also through psychological control (e.g., creating feelings of guilt in the children for what the parents do for them, pressuring the children to make a decision, not respecting their decisions). Overcontrol often originates from a parental self-centeredness that results in an inability to place oneself from the child’s point of view. All these parental behaviors limit children’s acquisition of independence and autonomous coping with daily life problems and illness-related difficulties (Givertz & Segrin, 2014; Sherman, 2015). Moreover, excessive control can lead to difficulties in family relationships and negatively affect parental well-being; indeed, some parents recognize and express concern about the presence of conflict and lack of communication with children. This finding is consistent with studies that emphasize the negative consequences of overparenting practices not only for the child but also for the quality of the parent–child relationship (Segrin et al., 2012) and for parental adjustment when children have a chronic illness (Baudino et al., 2022). As suggested by Walsh (2015), overparenting may initially be adaptive to manage change when illness enters the family system but has long-term negative consequences for family well-being.

A separate discussion must be made regarding enmeshment. Some parents show a relationship in which the boundaries between parents and children are lost, leading to parental identification with the children’s feelings and needs. Specifically, one interview revealed that a mother feels as ill as her daughter and wants to represent her in doctor visits and treatments. As outlined in the parenting literature, enmeshment is a psychological construct that is conceptually distinct from family cohesion (Barber & Buehler, 1996; Manzi et al., 2006). According to the relational-symbolic paradigm (Cigoli & Scabini, 2006), cohesion is characterized by the provision of support and emotional closeness among family members without compromising their autonomy; in contrast, enmeshment is a family pattern characterized by psychological fusion among family members that inhibits the individuation process and the development of children’s psychosocial maturity. According to this paradigm, enmeshment cannot be conceptualized as extreme cohesion (Manzi et al., 2006). For this reason, in our study, enmeshment was defined as a separate category from oversupport, although it is associated with overparenting practices. As described in the literature, enmeshment is generally associated with internalized symptoms and low psychological well-being in children (Barber & Buehler, 1996; Yahav, 2002). Similarly, for emerging adults with MS, family relationships characterized by enmeshment are likely to have negative consequences not only for autonomous coping but also for a successful separation-individuation process.

As for gender differences in parenting practices, the qualitative nature of our study does not allow us to draw generalizable conclusions. However, in the group of parents interviewed, it appears that it is mainly mothers who engage in overparenting practices, particularly in the forms of infantilization, enmeshment, and vicarious daily life management. Another interesting aspect related to gender differences in parenting is the consistency of parenting practices between mother and father. For example, one of the couples interviewed appeared to follow the same parenting practices based on indulgence, while two couples appeared to differ, with fathers reporting adaptive parenting and mothers reporting overprotection and overcontrol. Differences between parents have been noted in the literature on parenting, although they generally refer to healthy children and adolescents: Yaffe’s (2020) review showed that mothers tend to be more accepting and supportive, but also more demanding and autonomy-giving than fathers. Their parenting style is generally authoritative, while fathers tend to exhibit more authoritarian parenting patterns. Differences between parents were also found in parenting a child with a health problem (Pelchat et al., 2007). Mothers tend to deal with stress through emotional strategies and seeking social support (e.g., from family, friends, and other parents who are in the same situation), while fathers use both cognitive problem-solving strategies and are more action-oriented, although they are less likely to ask for help. All these differences are deeply rooted in differences in the socialization of men and women and are influenced by cultural variables (Pelchat et al., 2007). In the current landscape, where most studies focus on parenting ill children and adolescents, our preliminary descriptive findings provide interesting suggestions for developing future research on gender differences in parenting emerging adults with a chronic illness.

Our results should be considered in the light of the Italian socio-cultural context, where the transition to adulthood is often delayed and emerging adult children live with their parents for a long time. In Italy, the family represents the main source of economic support for its members, especially because of the difficulties for young people to find a job and become financially independent (STATISTA, 2023). Moreover, intergenerational support is often needed to compensate for the lack of adequate welfare services (Floridi, 2020) and the functions of care and support are mainly fulfilled by mothers (Carrà & Marta, 1995). As Scabini et al. (2006) pointed out, in Italy the transition to adulthood usually takes place within the family, so there are more difficulties in finding a balance in the relationship between parents and children. Italian family context with emerging adult children is often characterized by an “autonomous relatedness” (Manzi et al., 2012): autonomy and independence are encouraged by parents along with the maintenance of strong emotional bonding and relatedness with their offspring (Liga et al., 2017). This cultural model may make it difficult for parents to implement balanced support and control and previous studies on Italian healthy emerging adults showed that overparenting is more prevalent than in other countries (Pistella et al., 2022). Not only overparenting might reinforce offspring dependence, but also emerging adults’ attitudes might contribute to the maintenance of dependence. Most Italian emerging adults consider the emotional independence from parents as the least important criterion for adulthood (Crocetti & Tagliabue, 2016). Parental overinvolvement is often perceived as a form of warmth and they are often over-reliant on their parents for things that they should be doing themselves (Kaniušonytė et al., 2022; Smorti et al., 2022). Therefore, in families where boundaries between closeness and dependence are already blurred, the diagnosis of a chronic illness, like MS, can lead to even more complex family dynamics. Specifically, the disease often forces the family system to exert excessive control, which is often facilitated by cohabitation, and to provide excessive support that is not always motivated by an actual need of the young person. Emerging adults are also at risk of relying too heavily on parents for disease-related aspects that they could handle on their own. Dependence dynamics are thus reinforced and the transition to adulthood is made more difficult.

The study has some limitations. Because this was a qualitative and exploratory study with parent volunteers, a participant selection effect must be considered. Moreover, the qualitative approach purposefully used in this study limits the generalizability of our results, as in any qualitative studies. Moving from suggestion of the present study, future quantitative research should examine gender differences (both on the parents’ and children’s side), as well as inconsistencies in maternal and paternal parenting practices for the effects they may have on family dynamics. Finally, we have only examined the parents’ perspective. It would be useful to interview both parents and children to compare their views of parenting practices. Examining the views of both parents and children would provide practical guidance to help both cope with the illness diagnosis and make the family relationship adaptive.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine parental behavior toward emerging adults diagnosed with MS. Our findings contribute to the still scarce literature on parenting emerging adults with chronic illnesses with a deep insight into parental perceptions and have clinical implications for health professionals.

Some findings of the study can be extended to the parenting of emerging adults with other chronic illnesses. Relational dynamics between parents and sick emerging adult children, and in particular the delicate balance between autonomy and dependence, are key aspects to be considered in any chronic illness situation. Specifically, excessive parental concern, oversupport and overinvolvement can be elements that undermine the adaptation of the entire family system to the offspring’ chronic illness. Clinical centers should implement comprehensive psychological support for patients and the relationship systems (e.g., families) in which they are embedded, especially during the initial period after diagnosis of a chronic illness (Rintell & Melito, 2013). Parents should be given information about the disease to better manage their anxiety, which is often the initial cause of overparenting practices. Parents who are better able to control their emotions should also feel more able to establish appropriate relationships with their children by balancing support and control. In particular, parenting practices should promote the development of an equal relationship in which emerging adult children are treated as adults and their need for independence and autonomy is recognized.

Other results of our study should be considered with reference to specific aspects of MS that are the sudden diagnosis in emerging adulthood, the unpredictability of the disease course, and the need for medical therapies tailored to the patient. Parents may revert to dynamics typical of when their child was younger and demonstrate intrusiveness in the management not only of daily life, but also of medical treatments. Therefore, parents should be helped to support their children while encouraging their autonomous management of daily life and illness-related difficulties and therapies (Blundell Jones et al., 2017; Bonino et al., 2018). A very sensitive issue for parents is respecting children’s choices, especially regarding talking about the disease with them and outside the family (e.g., with friends, colleagues, employer). Parents should be helped to separate their own emotional experiences from those of their child, trying to take their child’s point of view but not putting themselves in their child’s place; in this way, they can help them and promote their autonomy. The implementation of adaptive parenting is not a goal that is achieved forever but requires constant changes that go hand in hand with the continuous process of adaptation to MS for both patients and their families.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7.

ATLAS of MS (2020). MS International Federation. https://www.atlasofms.org/map/global/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms

Baltes, P. B. (1997). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. The American Psychologist, 52(4), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.52.4.366.

Barber, B. K., & Buehler, C. (1996). Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(2), 433–441. https://doi.org/10.2307/353507.

Baudino, M. N., Roberts, C. M., Edwards, C. S., Gamwell, K. L., Tung, J., Jacobs, N. J., Grunow, J. E., & Chaney, J. M. (2022). The impact of illness intrusiveness and overparenting on depressive symptoms in parents of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing JSPN, 27(1), e12362. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12362.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4, 1–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030372.

Baumrind, D. (2012). Authoritative parenting revised: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting. APA.

Blundell Jones, J., Walsh, S., & Isaac, C. (2017). The relational impact of multiple sclerosis: An integrative review of the literature using a cognitive analytic framework. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 24(3–4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9506-y.

Bonino, S. (2021). Coping with chronic illness: Theories, issues and lived experiences. Routledge.

Bonino, S., Graziano, F., Borghi, M., Marengo, D., Molinengo, G., & Calandri, E. (2018). The self-efficacy in multiple sclerosis (SEMS) scale: Development and validation with Rasch analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 34(5), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000350.

Buchanan, R. J., Minden, S. L., Chakravorty, B. J., Hatcher, W., Tyry, T., & Vollmer, T. (2010). A pilot study of young adults with multiple sclerosis: Demographic, disease, treatment, and psychosocial characteristics. Disability and Health Journal, 3(4), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.09.003.

Calandri, E., Graziano, F., Borghi, M., & Bonino, S. (2022). The future between difficulties and resources: Exploring parents’ perspective on young adults with multiple sclerosis. Family Relations, 71(2), 686–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12630.

Calandri, E., Graziano, F., Borghi, M., Bonino, S., & Cattelino, E. (2020). The role of identity motives on quality of life and depressive symptoms: A comparison between young adults with multiple sclerosis and healthy peers. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589815

Carrà, E., Lanz, M., & Tagliabue, S. (2014). Transition to adulthood in Italy: An intergenerational perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 45(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.45.2.235.

Carrà, E., & Marta, E. (1995). Relazioni familiari e adolescenza [Family relationships and adolescence]. Franco Angeli.

Charmaz, K. (1983). Loss of self: A fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology of Health & Illness, 5(2), 168–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512.

Cigoli, V., & Scabini, E. (2006). The family identity: Ties, symbols and transitions. Erlbaum.

Cohan, S. L., Jang, K. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis of a short form of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20211.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104.

Cook, E. C. (2020). Understanding the associations between helicopter parenting and emerging adults’ adjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1899–1913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01716-2.

Crocetti, E., Rabaglietti, E., & Sica, L. S. (2012). Personal identity in Italy. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 138, 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad. Winter.

Crocetti, E., & Meeus, W. (2014). “Family comes first!” Relationships with family and friends in Italian emerging adults. Journal of Adolescence, 37(8), 1463–1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.012.

Crocetti, E., & Tagliabue, S. (2016). Are being responsible, having a stable job, and caring for the family important for adulthood? Examining the importance of different criteria for adulthood in Italian emerging adults. In R. Zukauskiene (Ed.), Emerging adulthood in an European context (pp. 33–53). Psychology Press.

de Ceuninck van Capelle, A., Visser, L. H., & Vosman, F. (2016). Multiple sclerosis (MS) in the life cycle of the family: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the perspective of persons with recently diagnosed MS. Families, Systems and Health, 34(4), 435–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000216.

Elder, G. H. Jr., & Shanahan, M. J. (2006). The life course and human development. In W. Daimon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 665–715). Wiley.

EUROSTAT. (2022). When do young Europeans leave their parental home? European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230904-1 (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

Floridi, G. (2020). Social policies and intergenerational support in Italy and South Korea. Contemporary Social Science, 15(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1448942.

Gagnon, R. J., & Garst, B. (2019). Exploring overparenting in summer camp: Adapting, developing, and implementing a measure. Annals of Leisure Research, 22(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2018.1452619.

Gagnon, R. J., Garst, B. A., Kouros, C. D., Schiffrin, H. H., & Cui, M. (2020). When overparenting is normal parenting: Examining child disability and overparenting in early adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01623-1.

Givertz, M., & Segrin, C. (2014). The association between overinvolved parenting and young adults’ self-efficacy, psychological entitlement, and family communication. Communication Research, 41(8), 1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365021245639.

Haegele, J. A., Holland, S. K., & Hill, E. (2022). Understanding parents’ experiences with children with type 1 diabetes: A qualitative inquiry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010554.

Hendry, L. B., & Kloep, M. (2002). Lifespan developmental resources, challenges and risks. Thomson Learning.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hullmann, S. E., Wolfe-Christensen, C., Ryan, J. L., Fedele, D. A., Rambo, P. L., Chaney, J. M., & Mullins, L. L. (2010). Parental overprotection, perceived child vulnerability, and parenting stress: A cross-illness comparison. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(4), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-010-9213-4.

Iani, L., Lauriola, M., & Costantini, M. (2014). A confirmatory bifactor analysis of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in an Italian community sample. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-84.

Inguglia, C., Ingoglia, S., Liga, F., Lo Coco, A., Lo Cricchio, M. G., Musso, P., & Lim, H. J. (2016). Parenting dimensions and internalizing difficulties in Italian and US emerging adults: The intervening role of autonomy and relatedness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(2), 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0228-1.

ISTAT (2021). Report natalità [Birth rate report]. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [National Institute of Statistics]. https://www.istat.it/it/files//2022/12/report-natalita-2021.pdf (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

Jiao, J., & Segrin, C. (2022). The development and validation of the overparenting scale–short form. Emerging Adulthood, 10(3), 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696821105278.

Kaniušonytė, G., Nelson, L. J., & Crocetti, E. (2022). Not letting go: self‐processes as mediators in the association between child dependence on parents and well‐being and adult status in emerging adulthood. Family Process, 61(1), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12656.

Kurtzke, J. F.(1983). Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology, 33(11), 1444–1452. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444.

Lerch, M. F., & Thrane, S. E. (2019). Adolescents with chronic illness and the transition to self-management: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescence, 72, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.02.010.

Liga, F., Ingoglia, S., Inguglia, C., Lo Coco, A., Lo Cricchio, M. G., Musso, P., Cheah, C., Rose, L., & Gutow, M. R. (2017). Associations among psychologically controlling parenting, autonomy, relatedness, and problem behaviors during emerging adulthood. The Journal of Psychology, 151(4), 393–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1305323.

Love, H., May, R. W., Cui, M., & Fincham, F. D. (2020). Helicopter parenting, self-control, and school burnout among emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01560-z.

Love, H., May, R. W., Shafer, J., Fincham, F. D., & Cui, M. (2022). Overparenting, emotion dysregulation, and problematic internet use among female emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 79, 101376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101376.

Lublin, F. D., Reingold, S. C., Cohen, J. A., Cutter, G. R., Sorensen, P. S., & Thompson, A. J., et al. (2014). Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology, 83, 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000000560.

Luebbe, A. M., Mancini, K. J., Kiel, E. J., Spangler, B. R., Semlak, J. L., & Fussner, L. M. (2018). Dimensionality of helicopter parenting and relations to emotional, decision-making, and academic functioning in emerging adults. Assessment, 25(7), 841–857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116665907.

Luyckx, K., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., & Berzonsky, M. D. (2007). Parental psychological control and dimensions of identity formation in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 546–550. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.546.

Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (2006). The person in context: A holistic interactionist approach. In W. Daimon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 400–464). Wiley.

Manzeske, D., & Stright, A. D. (2009). Parenting styles and emotion regulation: The role of behavioral and psychological control during young adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9068-9.

Manzi, C., Regalia, C., Pelucchi, S., & Finchman, F. D. (2012). Documenting different domains of promotion of autonomy in families. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.011.

Manzi, C., Vignoles, V. L., Regalia, C., & Scabini, E. (2006). Cohesion and enmeshment revisited: differentiation, identity, and well‐being in two European cultures. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(3), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00282.x.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Social Science Open Repository, 3–144. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282.

Messmer Uccelli, M. (2014). The impact of multiple sclerosis on family members: A review of the literature. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 4(2), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.14.6.

Miano, P., & Palumbo, A. (2021). Overparenting hurts me: How does it affect offspring psychological outcomes? Mediterranean. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9(3), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3081.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & McLean, R. D. (2021). Longitudinal predictors of helicopter parenting in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 9(3), 240–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820931980.

Odenweller, K. G., Booth-Butterfield, M., & Weber, K. (2014). Investigating helicopter parenting, family environments, and relational outcomes for millennials. Communication Studies, 65(4), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.811434.

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22, 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black Hawk down? Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007.

Pelchat, D., Lefebvre, H., & Levert, M. J. (2007). Gender differences and simililarities in the experience of parenting a child with a health problem: Current state of knowledge. Journal of Child Health Care, 11(2), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493507076064.

Pistella, J., Isolani, S., Morelli, M., Izzo, F., & Baiocco, R. (2022). Helicopter parenting and alcohol use in adolescence: A quadratic relation. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 39(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725211009036.

Rainone, N., Chiodi, A., Lanzillo, R., Magri, V., Napolitano, A., & Brescia Morra, V., et al. (2016). Affective disorders and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in adolescents and young adults with multiple sclerosis (MS): The moderating role of resilience. Quality of Life Research, 26, 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1466-4.

Raymaekers, K., Prikken, S., Vanhalst, J., Moons, P., Goossens, E., Oris, L., & Luyckx, K. (2020). The social context and illness identity in youth with type 1 diabetes: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01180-2.

Reed, K., Duncan, J. M., Lucier-Greer, M., Fixelle, C., & Ferraro, A. J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3136–3149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0466-x.

Rintell, D., & Melito, R. (2013). Her illness is a project we can work on together. International Journal of MS Care, 15(3), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2012-022.

Scabini, E., Lanz, M., & Marta, E. (2006). Transition to adulthood and family relations: An intergenerational perspective. Routledge.

Schreier, M. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis (pp. 170–183). Sage.

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3.

Schiffrin, H. H., Erchull, M. J., Sendrick, E., Yost, J. C., Power, V., & Saldanha, E. R. (2019). The effects of maternal and paternal helicopter parenting on the self-determination and well-being of emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(12), 3346–3359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01513-6.

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., Bauer, A., & Murphy, M. T. (2012). The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations, 61(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00689.x.

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., & Montgomery, N. (2013). Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 32(6), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.6.569.

Sherman, A. K. (2015). Overprotective and overcontrolling parenting of emerging adult survivors of childhood cancer: Links to coping styles, anxiety, and depression. University of Toronto. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=TC-OTU-71620&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=1032934792

Sirigatti, S., & Stefanile, C. (2009). CISS Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation. Standardizzazione e validazione italiana [Italian standardization and validation]. Firenze: Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali

Smorti, M., Ponti, L., & Cincidda, C. (2020). Life satisfaction linked to different independence-from-parents conditions in Italian emerging adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(4), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1634250.

Smorti, M., Sica, L. S., Costa, S., Biagioni, S., & Liga, F. (2022). Warmth, competence, and wellbeing: The relationship between parental support, needs satisfaction, and interpersonal sensitivity in Italian emerging adults. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19(5), 633–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1936492.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., & Beyers, W., et al. (2007). Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: Adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 43, 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.633.

Solari, A., Filippini, G., Mendozzi, L., Ghezzi, A., Cifani, S., Barbieri, E., Baldini, S., Salmaggi, A., La Mantia, L., Farinotti, M., Caputo, D., & Mosconi, P. (2008). Validation of Italian multiple sclerosis quality of life 54 questionnaire. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 67(2), 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.67.2.158.

STATISTA, 2023. Youth unemployment in Italy – Statistics & Facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/6292/youth-unemployment-in-italy/#topicOverview (Accessed Oct 9, 2023)

Strickland, K., Worth, A., & Kennedy, C. (2015). The experiences of support persons of people newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis: An interpretative phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(12), 2811–2821. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12758.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Trojanowski, P. J., Niehaus, C. E., Fischer, S., & Mehlenbeck, R. (2021). Parenting and psychological health in youth with type 1 diabetes: systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 46(10), 1213–1237. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab064.

Yaffe, Y. (2020). Systematic review of the differences between mothers and fathers in parenting styles and practices. Current Psychology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01014-6

Yahav, R. (2002). External and internal symptoms in children and characteristics of the family system: A comparison of the linear and circumplex models. American Journal of Family Therapy, 30(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/019261802753455633.

Walsh, F. (2015). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035.

Winner, N. A., & Nicholson, B. C. (2018). Overparenting and narcissism in young adults: The mediating role of psychological control. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 3650–3657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1176-3.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all parents who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by Cosso Foundation, Pinerolo, Torino, Italy. Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the “San Luigi Gonzaga” Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol no. 0013772).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Graziano, F., Borghi, M., Bonino, S. et al. Parenting Emerging Adults with Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Analysis of the Parents’ Perspective. J Child Fam Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02845-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02845-8