Abstract

In Japan, many fathers consider their spouse to be their children’s primary parent while casting themselves in a supporting role. Yet, in the majority of reported child maltreatment cases in Japan, the child’s father is recorded as the perpetrator. This may seem somewhat puzzling, given that primary caregivers are recorded as the perpetrator of maltreatment in other cultures. This study qualitatively analyses the parenting experience of 11 Japanese fathers and their reflections on child maltreatment risks. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with fathers of pre-school aged children from middle-class families who had no reported history of child maltreatment. Using qualitative content analysis through a process of condensing, coding and categorising, we arrived at the following theme: fathers aspire to be an active parent, while respecting and supporting their spouses, but anxiety and stress trigger impatience and frustration during parenting. The fathers reported that they are more likely to maltreat their children, especially boys, in situations which triggered anxiety and frustration. Anxiety is particularly heightened when they feared public embarrassment. These findings are discussed with reference to the Japanese social and cultural context, and contrasted with previous research into the parenting experiences of Japanese mothers. The findings indicate that fathers may benefit from tailored support programmes which strengthen their self-efficacy before building resilience for the challenging situations they may encounter as fathers.

Highlights

-

Japanese fathers at low risk for maltreatment were interviewed about their parenting experience.

-

Social and professional barriers inhibit fathers’ desire to be actively involved as parents.

-

Participants’ parenting ideals are threatened in stressful or anxiety-provoking situations.

-

Fathers may perceive themselves to be a secondary and less competent parent than mothers.

-

The data may reflect a societal value system representative of Japanese culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Child maltreatment is globally recognised as a significant risk to the health and well-being of children, both during childhood and throughout their lives (Lansford et al., 2002; Anda et al., 2006; King et al., 2011; Font & Maguire-Jack, 2020). The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) reports that in the year 2018, at least 1738 children were reported to have lost their lives to abuse and neglect in the U.S. alone (Children’s Bureau, 2019). Evidence on intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment suggest that maltreatment develops through an interplay of parental health, socioeconomic status, and child development as well as family and life stressors, and becomes entrenched over time (Berlin et al., 2011; Egeland, 1988; Rivera et al., 2018). Therefore, all research into child maltreatment must take into account social, cognitive, emotional and cultural factors. Research on child abuse and maltreatment tends to focus on risk factors based on records of maltreatment cases. There is a dearth of research taking into account the thoughts of those who have no history of reported child maltreatment. There is a potential that even currently non-maltreating parents and caregivers may have had reflections on whether they may sometimes treat their children in a way that may be considered problematic, or even maltreatment. Research on non-maltreating or low-risk families may therefore provide a unique window into the mechanisms by which ordinary parental beliefs and reflections may yet be relevant to child maltreatment.

Parenting stress is a persistent challenge for parents and families, one which requires support for the entire family, not just the mothers (Zhang et al., 2016). Consistent with this, a previous study conducted in Japan has shown that mothers believe that they are more likely to maltreat their children when they are stressed or their emotional states are heightened (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2017). In the study, low-risk Japanese mothers remarked that their strong desire to live up to their own parenting ideals helped them to successfully resist the impulsive urges which pull them towards problematic behaviour. However, the mothers were also afraid that pursuing their parenting ideals may mean forcing their agenda onto their children, while disregarding children’s own wishes or desires (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2017). These findings seem to suggest that parenting involves conflicting cognitions and motivations at times. Protective factors associated with low-risk families, such as access to economic resources, may not necessarily exempt them from such psychological challenges.

For example, our earlier work interviewing Japanese parents suggested that fathers assumed a passive role as a parent, and that mothers and fathers were in agreement in their remarks in the interviews that it was the mother who took a predominant role as a parent (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2019). Findings from a recent national survey are consistent with the perception that men in Japan tend to expect women to prioritise family over work (White Paper on Gender Equality, 2016).

While research on mothers predominates in the literature on parenting, fathers’ perspectives and experiences as parents are unique, and distinct from those of mothers (Carlson & Klein, 2014).

In the broader international literature and across cultures, the findings are much more diverse and nuanced. While there is a tendency that mothers spend more time than fathers with their children, particularly during infancy (Roopnarine et al., 2005), this can be highly varied between cultures and the age of children: while fathers in rural Muslim families in Malaysia estimated that they only spent a fifth of the time that their mothers would spend with their children (Hossain et al., 2005), the amount of time was similar in Brazilian families (da Cruz Benetti & Roopnarine, 2006). Studies also show that there are specific contexts in which fathers may make a positive impact on their children’s development: for example, fathers have been reported to take an active role in playing with their children (Hossain & Roopnarine, 1994), and fathers can have a significant impact on their children’s education (Roopnarine et al., 2006). Studies outside of Japan report that as parents, men desire to protect their children and wish to be an active presence in their children’s lives (Lamb & Lewis, 2013; Vinjamuri, 2016). Paternal participation in family life has been shown to benefit the health and well-being of children (Gallegos et al., 2019) as well as marital relationships (Xue et al., 2018). Based on these findings, Japanese fathers appear as if—regardless whether this is their intention—they are missing the opportunities to contribute more as parents compared to other cultures. These findings may also suggest that there are factors that drive Japanese fathers and their families to accept the arrangement where mothers take a more active role as parents.

Another culturally distinct feature of the paternal role in Japan, is the issue of paternal involvement in reported child maltreatment cases; over 70% of reported cases of child maltreatment (1448 out of 2024 cases) recorded in the country were accounted for by fathers (including stepfathers) or other male relatives (Japan Police Agency, 2020). Paternal involvement in child maltreatment may be particularly significant in Japan compared to other countries; for example, mothers constituted the largest perpetrator group in the aforementioned U.S. estimate of over 1700 deaths by child maltreatment (Children’s Bureau, 2019). A Japanese study has linked paternal maltreatment to a range of factors including the number of children in the family, paternal education and self-efficacy, and maternal maltreatment of the children (Sugimoto & Yokoyama, 2015). A more in-depth analysis of Japanese fathers’ experiences would be valuable, as it may shed light on whether there is a link between the more passive caregiving role and risk factors for child maltreatment.

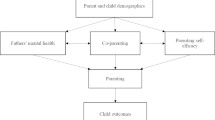

The distinction between appropriate disciplining and abusive behaviour towards children has been a point of contention globally (Coleman et al., 2010). While corporal punishment or harsh disciplining are clearly harmful for the well-being of children (Gershoff, 2002; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016) cultures mediate attitudes and beliefs regarding discipline of children; for example, corporal punishment of children remains common in some cultures (Van der Kooij et al., 2018). Maltreatment has also been linked to other factors such as economic resources or paternal education levels (Roopnarine & Yildirim, 2019). Further, a recent meta-analysis (Ayers et al., 2019) has found that parental mental health during the perinatal period posed a significant risk for child maltreatment; in particular, the meta-analysis confirmed mental health issues as a risk factor for all the studies in the analysis which included fathers, regardless of the type of mental health issue. These findings seem to suggest that paternal attitudes about fathering, and fathers’ mental health may be linked to fathers harming their children.

In Japan, recent years have seen both Japanese academics and national media take an active interest in what distinguishes 虐待gyakutai, ‘abuse/maltreatment’ and しつけshi-tsu-ke, ‘discipline’ (e.g., Baba, 2015; Ninomi et al., 2004; Kato & Fujioka, 2020). According to Japanese media coverage, perpetrators of maltreatment often state that they intended to engage in しつけshi-tsu-ke, ‘discipline’, rather than虐待gyakutai, ‘abuse/maltreatment’ when they hurt their child (Chugoku Shimbun Digital, 2020). While ‘discipline’ is often contrasted with praise in English (Jackson et al., 1999), the Japanese term しつけshi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’ refers to parenting which teaches children to differentiate between desirable and problematic behaviour (Japan Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, 2020). An emerging understanding is that differentiation of the two terms varies, even amongst non-maltreating parents. In a large-scale Japanese survey, where respondents were mostly mothers, many participants were unsure which behaviours would be deemed abusive and assumed shouting or even some forms of physical violence, such as hitting a child’s bottom, may be part of しつけshi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’ (Lee et al., 2012).

The ongoing debate highlights the need to study how parents understand and distinguish the two concepts in their everyday parenting. It may inform what kind of actions parents consider good or even ideal (しつけshi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’), and which actions maladaptive or abusive (虐待 gya-ku-tai ‘maltreatment’). It would also help us to understand which problematic behaviours are within parental awareness.

Our aim in the reported research was to explore Japanese fathers’ perspectives and reflections on their parenting experiences, focussing on situations or mental states in which fathers felt they may maltreat their children. We conducted interviews with fathers in a low-risk population group in Japan. In our interviews, we distinguished しつけshi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’ from 虐待gyakutai ‘maltreatment’ in accordance with the differentiation by the Japanese Paediatric Society, using 虐待gyakutai, ‘maltreatment’, to refer to “behaviour and situations which put the child’s well-being and safety at risk, regardless of the intention or motivation of those involved” (Japan Pediatric Society, 2014). Under this distinction, an action with the intention to engage in しつけshi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’ could still constitute child maltreatment. We employed qualitative content analysis for our analysis method, in order to meet the goal of achieving a set of systematic descriptions about mental states—including cognitions and emotions—as experienced by the participants, focussing on risk factors of maltreatment.

While it is important to distinguish maltreatment from other parenting behaviours, in reality, parenting is a complex and demanding task that is ubiquitously undertaken in everyday life of parents. Any parent, even a low-risk parent, might experience mental states that may draw them towards maltreatment. By studying a low-risk, non-maltreating sample, the study aimed to analyse the psychology of parenting without a history of child maltreatment. We anticipated that parents who had not been reported for maltreatment would be willing to speak more openly about their perceived risk factors for maltreatment. Thus, potentially sensitive questions about parenting could be asked ethically while eliciting more accurate responses based on participants’ typical everyday experience.

Method

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the first author’s institution (approval reference number: 29–253 (8869). We obtained informed consent from each participant on the day of their interview after ensuring that any questions had been satisfactorily answered. Interviews used the term しつけshi-tsu-ke, ‘discipline’ to refer to both affirming and corrective actions, such as praising, nurturing, chiding or, more broadly, caring for children. Consequently, しつけshi-tsu-ke, ‘discipline’ was clearly contrasted with 虐待gya-ku-tai, ‘abuse/maltreatment’. Before starting the interview, the interviewer ensured that each participant understood the distinction. During this process, the interviewer also provided an overview of different types of maltreatment: psychological, physical, and sexual abuse and neglect.

Participants

Eleven fathers of children aged 0–6 years agreed to take part in the study. In line with the focus of our study on low-risk families, our recruitment criteria were as follows: aged 20 years or above, married to the mother of their child(ren), and neither the fathers themselves nor their children had known mental health issues or developmental problems. Eligibility of participants was verified based on self-declaration of each participant against the recruitment criteria. We focused on fathers of preschool aged children, following a recent U.S. report that most child maltreatment fatalities (70.6%) were recorded for children under the age of 3 (Children’s Bureau, 2019). Although equivalent data in Japan was sought, it was unavailable. In Japan, children usually start school around age 7. The pre-school period coincides with the developmental phase in which fundamental attachment relationships are formed (Groh et al., 2017). We thus chose the above age group to focus on the phase of childhood likely to be most vulnerable to death from maltreatment, but also most critical for parent-child relationships.

As summarised in Table 1, the mean age of fathers was 37.9 years (range 33–44 years). Nine participants had 1 child (6 boys and 3 girls) and the remaining two families had one boy and one girl each. In 8 out of the 11 families, both parents worked. All participants were educated at least to degree level. In exchange for their participation, participants received an electronic gift card worth 3000 Yen (approximately 27 U.S. Dollars) at the time of their interview.

Initial attempts to recruit participants via opportunistic sampling through 20 randomly selected kindergartens and nurseries in the Tokyo area were unsuccessful, likely because it is often mothers who take children to childcare services. Difficulties in recruitment of fathers are common in the international literature on fatherhood (Lewis & Lamb, 2006; Mitchell et al., 2007). As a consequence, we reviewed our recruitment strategy and were able to recruit four participants at a community midwifery clinic which held regular events to support parents with young children. One of these participants volunteered to connect us with 7 further participants within his parenting network. The participants were thus recruited through a combination of opportunistic and snowball sampling.

Procedure

Data collection

Our data collection took place between March 2018 and January 2019 using semi-structured interviews. This method allowed some freedom for participants to answer questions spontaneously while permitting the research team to ask follow-up questions. The interview guides (Appendix 1) were organised by the following 4 themes: 1. Family structure and childcare arrangements; 2. Times or events when participants felt anxious as parents; 3. Any of their past parenting behaviour that made them think about the difference betweenしつけ shi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’ and 虐待 gyakutai ‘maltreatment’; 4. Their understanding and attitude to しつけ shi-tsu-ke ‘discipline’. Interviews varied in length between 34 and 72 min (M: 52 min). As a qualitative study, our data depended on the trust and rapport between the researcher (Yasuko Hososaka) and the participant. Therefore, much care was taken to ensure that sessions were arranged to suit participants’ convenience and that they felt at ease to share their experiences. The interviews took place in public locations which allowed for some privacy, for example a rear table at a café or an available room at a clinic. Interviews were recorded with participants’ consent using a digital voice recorder. All interviews were conducted by the first author (Yasuko Hososaka), who also noted down observations and reflections after each interview.

Data analysis method

The analysis employed a qualitative content analysis method, as described in Graneheim and Lundman (2004), following a procedure of condensing, coding, and categorising while retaining contact with raw data. The method was deemed the most suitable for the current purpose, of capturing and describing a range of responses from participants, such as aspirations, experiences, emotions or cognitions related to fatherhood. We sought to gather complex, and deep mental constructs from participants, for which we anticipated a wide variety of responses. Because of this, we aimed to systematically identify and describe the participants’ responses, rather than developing a theoretical construct as in grounded theory analysis. The analysis subsequently served the overall goal of identifying how fathers describe their stance in parenting, and provided descriptions about their awareness of when and in what ways they feel they may be at risk for problematic parenting behaviours, including maltreatment.

All 11 interviews in the sample were transcribed verbatim from the recordings. The texts were studied by the first and second authors, in conjunction with the notes taken by the first author after each interview. After familiarising themselves with each participant’s transcribed responses (i.e. the unit of analysis, Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), the first and second authors each divided and condensed the responses into units of meaning (‘codes’). Relevant remarks were thus grouped and assigned codes while the remaining data were excluded from further analysis. The two authors compared their codes at this point, and any significant differences were resolved by discussion, arriving at a set of revised codes. At the end of the analysis process, these were sorted into sub-categories, and further threaded into categories. The process up to producing this preliminary set of categories was led by the first author; the categories at this point were discussed with the second author, who served as a reviewer to raise questions, or to seek further clarification. The revision process between the two authors concerned: a) phrasing of codes, sub-categories and categories; b) verifying the path between raw data and units of meaning; and c) consulting any part of the text where the first author felt in need for a second opinion. Finally, the underlying meaning, that is, the latent content, of the categories (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), were organised into a theme.

The above analysis process progressed in parallel with recruitment and interview transcription, in order to collect data and to discern a saturation point in sampling. Eight participants were first recruited, interviewed, and their responses analysed; at this point, the two authors engaged in the discussion as described above, to review the analysis content and its structure. Thereafter, data collection and analysis were repeated with a new participant, a process which was repeated until the process for the 11th participant was complete, where data was deemed to have reached a saturation point. Subsequently, the first author shared the entire raw data and analysis with the second author, and the entire analysis was discussed until it was approved by both authors. As the analysis progressed, emerging hypotheses were tested in interviews with additional participants; this was implemented while adhering to the interview guide (Appendix 1). However, follow-up questions were asked during the interview, so that the interviewer could confirm she had understood participants correctly. The cycle after the first 8 participants was repeated until saturation, i.e. until interviews no longer yielded new information which prompted addition or revision of the codes or subcategories. Our analysis reached a saturation point when 11 fathers had been interviewed, forming the final sample for our study.

Data trustworthiness and credibility

Audit trails were developed to ensure a transparent coding process which can be independently confirmed (Carcary, 2009). Based on initial codes which were developed, led by the first author, the first and second authors discussed and confirmed the categories and subcategories. The two authors consulted each other throughout the process to check for any inferential leaps or biases. In order to verify the results of the analysis, 9 out of 11 of our participants checked and approved the codes derived from their interviews and the titles of the codes. The 4th author, who is a bilingual speaker, led the translation of the analysis structure from codes up to categories. The 3rd and 4th authors were given access to the analysis to verify the process from subcategories and categories, with all authors taking part in a discussion to approve the theme presented in this paper. The 3rd author also contributed to refining the English-language expressions and concepts in cooperation with the 4th author. The resulting key categories, subcategories and codes are summarised in Table 2.

Results

Five categories emerged from analysis, supported by 23 sub-categories and a total of 337 codes across sub-categories, as summarised in Table 2. The categories were: 1. Parenting perspective as fathers; 2. Parenting attitudes grounded in own childhood experiences and marital relationship; 3. Unexplainable anxiety of bringing up a child; 4. Practical, professional and social barriers in parenting as fathers; and 5. Potential risk moments for maltreatment during parenting. The first two categories summarise remarks from the participants that describe a positive stance as fathers: an understanding of fatherhood as active involvement in children’s lives according to progressive values and ideals (Category 1); and the endeavour by fathers to pursue their ideals described in Category 1, while managing negative experiences with their own parents, anxieties as fathers, or resolving different views with their spouses (Category 2). The subsequent two categories describe challenges that participants perceive as fathers: perception of themselves as lacking in confidence and expertise as parents, leading them to feel anxious about their own parenting skills and about impact their parenting may have on their child’s future (Category 3); social, practical and professional barriers which they feel hinder active involvement as parents (Category 4). The final category described their awareness of an inclination to resort to physical punishment or being impatient with their children, when a level of anxiety or frustration was heightened (Category 5). We have summarised the categories into an overall theme as: Fathers aspire to be an active parent, while respecting and supporting their spouses, but anxiety and stress trigger impatience and frustration during parenting.

-

(A)

Categories 1 and 2: Fathers striving to do their best as parents.

Several participants mentioned their willingness, even eagerness, to play an active part in their children’s upbringing. Fathers’ emotional connection with their children and respect for their offspring were considered positive and important elements of parenting. For instance:

Well, it may be just a bit of idealism, but when I think about which area of parenting is most valuable and is worth making an effort on, it is how to talk to my child to make a connection with her. Hm, yes, if I could pick one thing I really think about, it’s that, how can I communicate with my child? (B42, Category 1, Subcategory 2).

In this remark, B indicates active paternal involvement in parenting both in his theoretical ideals (‘worth making an effort on’) and in practice (‘one thing I really think about’). The emphasis he places on father-child communication as a parental ideal, stands in stark contrast to the traditional model of a hierarchical familial relationship, typical within traditional Japanese culture.

According to this view, corporal punishment was generally regarded unfavourably, as illustrated in the following statement by participant C:

No, I don’t think I’d ever resort to physical force. Hm, I wonder why I feel this way, though… I think I am influenced by today’s society and its values. At work, even little things can develop into a case of harassment, one could be sued over such things (C28, Category 2, Subcategory 2).

Reflecting on the reasons for his views (‘I wonder why I feel this way’), participant C links his rejection of physical punishment to modern social values. He perceives his views of physical punishment as a direct consequence of social influences such as the unacceptability of violence in the workplace. Implicit in this statement is a contrast between ‘today’s society’ and traditional parental ideals.

Other participants described how they came to hold the same position of relegating a harsh parenting style through their early experience of receiving such a treatment as a child from their own parents:

My own parents used to raise their voices. It wasn’t violent, but their way was emblematic of the pre-war [World War II] generation…maybe prototypical of the [father as] ‘head of the house’ type approach, or maybe the sort of thing that may have happened in a town’s factory, in that old-fashioned way… It may have been accepted in the Showa era [1926–1989], but I feel rather against such a mentality, and even feel quite decisively resistant to it, in that I won’t allow it to be passed onto my child, something like that (B52, Category 2, Subcategory 1).

In this remark, B describes his experience of being raised within a traditional Japanese family. His own father, who likely served as B’s earliest example of fatherhood, was the head of a hierarchical family and employed a harsh parenting style. However, B clearly relegates this model of fatherhood to bygone times and does not plan to conform to this role traditionally ascribed to fathers.

While the fathers quoted above articulated their visions to pursue an active role in parenting, participants also described how they nevertheless, found themselves in an auxiliary position, in order to support their spouses:

If I were on my own [as a parent], I would have thought more about how to raise my child. For example, I want to do this, that or I want to bring up my child in such and such ways. This is the problem for me; if I were really involved in my child’s life, I would have my own stance and goals as a parent. But the boss here is my wife and we are a bit like a company director and an employee. I may have ideas and make suggestions to her but then if she says “No, it should be like this instead.”, then I am inclined to say “All right.”. At least, there is no conflict this way. (J22, Category 1, Subcategory 6).

While participant J had the desire to get more involved in his child’s life as a father, he perceived that the primary carer was his spouse, the child’s mother. Further, J valued agreement as a couple over conflicts or discussions, which acted as his own internal force to supress his desire to take initiative as a parent. This left him in the position of secondary caregiver with little direct influence over his child’s upbringing. The above quotation makes it apparent that he is mildly frustrated to be trapped in a vicious cycle of being and staying in a subordinate parenting role. However, he is also accepting of the role; by putting his wife’s opinions first, he believes that he contributes to a harmonious relationship with his wife. Also implicit in this quotation, is the benefit of this harmonious relationship for their child and for them as a unit.

-

(B)

Categories 3 and 4: Challenges and barriers perceived by participants as parents.

While participants themselves criticised the traditional role of the less involved and authoritarian father, they described societal expectations which still conform to this stereotype. Both workplace and community expectations were seen as direct barriers to parenting in accordance with the fathers’ own progressive values. Participant E explains as follows:

Upon becoming a parent, I looked up my company’s policies, but it’s disadvantageous taking paternity leave. For example, my company allows unpaid leave when paid leave has been used up but the rule states taking extra leave works against assessment for bonuses and promotions (E17, Category 4, Subcategory 2).

In this remark, participant E describes a situation in which paternity leave is disincentivised by his employer. As a result, E felt that it would not be worthwhile making the extra effort to be involved as a father. Such policies prevent the participant from getting more involved in his child’s life and, more generally, perpetuate the gap between mothers’ and fathers’ caregiving opportunities.

However, hindrances to paternal involvement extend beyond employment and financial disincentives to social barriers. Participant A reports an example:

The majority in the community [of parents] are mothers and my constant challenge was in getting into the group. If I take my child to a community centre, it’s mothers that approach you (A24, Category 4, Subcategory 1).

Here, A comments on his experience of parenting as a domain occupied primarily by women and he conveys his unease about his minority status in the parenting community. The absence of other men in the parenting community is experienced as a further barrier to parenting involvement and access to parenting support.

Participants also described their perception that fathers fundamentally lacked the knowledge in parenting in comparison to mothers:

I just don’t think fathers have constructive knowledge as parents, particularly when the child is first-born. I mean, knowledge about bringing up a baby, its method or expertise are not that well known in general (amongst fathers). (I115, Category 3, Subcategory 2).

In the above quotation, participant I seems to be assuming that the skills necessary for raising a child are difficult to gain; he also seems to be alluding to the view that while fathers struggle to know what to do with their child, particularly their first-born, this is not true of mothers. Similarly, other participants cited tasks which can only be performed by mothers, such as breastfeeding, as reasons for their hesitancy to parent more actively.

-

(C)

Category 5: Fathers’ awareness of risk factors for maltreatment.

Ten out of 11 participants mentioned potential risk factors for child maltreatment. Participants described resorting to physical punishment when they were stressed and frustrated. For example:

I am anxious about troubling neighbours as we live in a flat. I feel I must do something when my child cries, and the overwhelming sense contributes to my stress levels. It is the same when my child cries on a train. I feel panicked if my child suddenly makes a fuss or cries. I am most worried about causing trouble when out in public places. I feel responsible and flustered. It’s possible that others just think ‘Ah, the child is crying.’ as in the case of the train or our neighbours don’t really hear us much. I find that I am often overwhelmed by stress and panic when my child cries. I have in fact felt that I wanted to quieten my child no matter how, just cover her mouth or hit her. (G80, Category 5, subcategory 3).

Participant G describes feelings of stress and panic when his child cries, to the point that he feels compelled to use physical force to quieten her. This is exacerbated when G believes that others may be inconvenienced by the child’s crying, for example when in public.

In addition to stress, frustration with the child’s behaviour was cited as another important risk factor for physical punishment and described by ten out of eleven interviewees. Participant F relates:

I try and tell my child calmly twice, maybe thrice, but when I don’t get a response, the most obvious next step that comes to my mind, is to raise my voice. I raise my voice, whether consciously or unconsciously. (F24).

Participant F describes raising his voice as a method to bring about the child’s compliance with instructions. However, as F himself suggests, he is aware that raising his voice is not an optimal or appropriate action, and he only uses the approach when the child’s repeated non-compliance has resulted in feelings of frustration.

In addition to situational risk factors, participants also reported that the children’s gender and birth order influenced their choice of whether or not to resort to physical force (Category 5, Subcategory 1):

I seem to hold a belief that one does not hit girls (D23).

I was playing with my two nephews; […] they were getting carried away, and not showing me any respect, so… I hit them. Then I realized that I am distinguishing boys and girls. While I may not have done this to my daughter, I may be capable of resorting to physical means for boys (H32).

Participants D and H described an unconscious (‘I seem to’; ‘Then I realized’) resistance to physical punishment when disciplining a girl over boys.

Participant F also gave an account on treating children differently according to birth order:

I don’t think it goes as far as maltreatment, and I don’t want to compare my children, but I wonder if I say things like “you are the big brother” or “you can do it, you are older” and setting unreasonable expectations for my eldest to be particularly mature and independent (F22)

Notably, participant F does not believe this differential treatment extends to maltreatment. However, he notes that he expresses significantly higher expectations towards his older child while not putting similar pressure on the younger sibling.

In sum, participants had an understanding of fatherhood and parenting based on modern social ideals. This includes an active involvement in their children’s lives and nurturing parenting. Participants also described that the pursuit of their parenting goal involved some grit, such as protecting their child from negative childhood experiences which they suffered as children. Others also explained about a value in accepting a non-primary parenting role, in order to honour their spouses, thereby providing a harmonious relationship in their family. Societal pressures push fathers further into a non-primary parenting role, which is more consistent with the traditional paternal role, and against their aspirations as parents. As a result, the participants felt that parenting was unevenly shared between them and their spouses. The participants also felt that as parents, they were less competent and important than their wives. Participants reported the urge to use physical punishment when they feel stressed and frustrated with their children’s behaviour. Fathers reported a greater willingness to use physical force against boys than against girls and put greater pressure on older siblings.

Discussion

The present study set out to examine Japanese fathers’ understanding of their own parental role, and to investigate whether there is a link between their conception of parenthood and child maltreatment. We applied a qualitative content analysis method to data gathered through interviews with eleven fathers from typical middle-class households in Japan. Analysis allowed us to identify an aspiration of fatherhood for active parenting, as well as barriers against its pursuit as two competing concepts of fatherhood in Japan, and point out a possible connection with maltreatment. We found that physical punishment does not form part of our interviewees’ understanding of ideal parenting. However, in instances in which they are stressed or frustrated, fathers may resort to physical punishment based on a traditional conception of fatherhood.

As previously reported (Xue et al., 2018), the participants in the sample desired to be involved in their children’s lives and to raise their offspring in a nurturing manner. This might be expected to forestall, rather than contribute to, child maltreatment. Indeed, both quality and quantity of paternal input (Lamb & Lewis, 2004), such as affective and warm parenting (Chung et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020), have been shown to contribute positively to child development. For example, the quality of father-child relationships has been shown to serve a protective function against substance use among at-risk adolescents (Yoon et al., 2018).

However, the participants were aware that their pursuit of involved fatherhood was inhibited by societal, domestic and professional barriers. As a result, they tended to view themselves as the less available, subordinate parent. This is indirectly reflected in an anecdotal observation during the interviews: some of the participants commented that they had not previously thought about their stance as a parent. Some of these comments were followed by some spontaneous reflections that it was because they were not involved (as much as they wish to) in parenting. The fathers’ assumption that they were not in a leading role appeared to be linked to their sense of inadequacy and incompetence as parents, further reinforcing the caregiving hierarchy. This finding is consistent with previous research which has suggested that fathers face distinct and possibly additional barriers to parenting. A systematic review of peri-natal support programmes found that few interventions were available to fathers (Lee et al., 2018). Further, paternal involvement has been found to be positively correlated with higher levels of education or income, and lower levels of inter-parental conflict (Wong et al., 2013). Despite the importance of paternal input, these findings suggest that while support for fathers exist, these tend to be available only to more affluent families.

Despite their wish to parent actively, the fathers in our sample doubted whether they were qualified to do so, and displayed fear of any long-term negative impact their parenting may have on their children. Given that participants frequently drew comparison between parenting and their working lives, we tentatively suggest that some of the fathers in our sample may have drawn strong parallels between parenting and employment, thus professionalising parenthood. For example, the participants assumed that systematic understanding and skills were needed for successful parenting, similar to requirements in the professional world. Given the myriad barriers facing paternal involvement, fathers are more prone to feeling undervalued and excluded from the parenting scene (Panter-Brick et al., 2014). This may partly explain the participants’ concern for their competence as parents in the present study. It is unclear from the current study whether fathers exclude themselves deliberately, perhaps to legitimatise their subordinate status, or whether this is in reflection of the long working hours which are considered a norm in Japanese society. The current study suggests that in the least, such a subordinate role is not what fathers desire as parents. Rather, fathers face a myriad of barriers and their own unsureness as an additional barrier, as to whether they are able to make a worthy contribution over and above that of their spouses.

Research shows that family well-being as a whole suffers when an excessive parenting demand is placed on mothers. A European study with UK and U.S. full-time working mothers found that maternal gatekeeping behaviours which prevent co-parenting were associated with maternal preoccupation with perfection, with maternal burnout, and with poorer reported work-family balance for mothers (Meeussen & Van Laar, 2018). Similarly, paternal involvement has been found to correlate negatively with mothers’ proactive attitudes, suggesting that couples adjust their parenting contributions in a complementary way (Gaertner et al., 2007). These findings resonate with the current study, where fathers explained that they would settle for a subordinate role in order to honour their wives and to bring a greater family harmony. However, these findings suggest that, where such an adjustment becomes a default arrangement, it may not in reality, provide a long-term benefit for the family.

Furthermore, fathers’ acceptance of a secondary role may itself impact negatively on the quality of father-child relationships. Such suboptimal quality of relationships could in turn act as a risk factor for paternal maltreatment of their children. Qualitative research into the experiences of public health nurses in Japan found that fathers with a history of child maltreatment were often unable or unmotivated to seek an emotional connection in the family, and were afraid of communicating with the child’s mother (Ueda et al., 2014). Although the study does not establish the direction of any causal relationship between the two factors, the finding reiterates that the quality of father-child relationships is a factor in child maltreatment.

Indirectly, fathers’ lack of confidence in their parenting expertise, and their perceived inability to deal with a child’s unwelcome behaviour may induce intense feelings of stress and frustration in fathers. These may prompt fathers to deviate from their ideal parenting behaviour. Anger and frustration have been linked to negative (Pidgeon & Sanders, 2009) or inconsistent parenting (Lengua, 2008). Likewise, the frustration-aggression theory, which states that aggression develops as a reaction to frustration (Dollard et al., 1939), has been supported by evidence from the domain of child maltreatment. For example, previous studies have linked low frustration tolerance and emotion dysregulation with a greater risk for child abuse in both mothers and fathers (Rodriguez et al., 2015, 2017). Further, problematic behaviour in children has been associated with paternal psychological distress and the use of harsh disciplinary measures (Gulenc et al., 2018). Children prone to anxiety or frustration are, in turn, at increased risk of being subjected to negative parenting behaviour (Kiff et al., 2011), which suggests a vicious cycle of mutually reinforcing negative feelings and behaviour. In our sample, remarks offered by participants suggested that they were able to meet their own parenting goals while they felt calm and frustration levels were low. However, as stress, anxiety or frustration levels rose, their conscious effort was threatened by aggressive urges and impulsive actions. The process was articulated by father F who reported that he tries speaking calmly to his children, but when he is repeatedly met with non-compliance, he becomes more short-tempered and impulsive (F24).

Previous research has reported that parental early experience of physical punishment is more likely to be transmitted to children when it is mediated by a favourable attitude towards such punishment (Wang et al., 2018). The finding contrasts with our analysis, which portrays a much more complex relationship between the role of early experience and current parental beliefs and actions. A recent meta-analysis of 51 studies found that cognitive bias towards physical abuse had a small- to medium-sized effect on child maltreatment (Camilo et al., 2020). This is more consistent with our present research, which suggests an interplay between attitude towards physical punishment and cognitive control: we found that participants were critical of resorting to physical punishment, and yet reported a greater inclination to lash out at their children in situations in which they felt stressed and frustrated. Based on the findings by Camilo and colleagues, we might speculate that in the current study, cognitive control mediated the likelihood of fathers to resort to physical punishment. It is also a possibility that the low-risk sample in the current research was more capable of greater cognitive control than at-risk groups who likely carry additional risk factors such as life stress.

Nonetheless, early experience of maltreatment has been recognised as a risk factor in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (Yehuda et al., 2001; Lünnemann et al., 2019). Being subjected to maltreatment as a child is a devastating trauma, but it is also a significant risk factor for domestic violence later in life, as either a victim or a perpetrator of violence, abuse or neglect (Van Wert et al., 2019). The literature suggests that fathers may be at an additional risk for such a transmission given they, as boys, were more likely to be physically disciplined (Wang et al., 2018). The remarks analysed in the present study show that the fathers in the sample were aware of their ‘ghosts in the nursery’ (Fraiberg et al., 1975), and were determined to stop their negative experiences from tainting their children. Caution is required in further interpreting our data, since they consist only of retrospective self-report and we do not hold any other information on participants’ childhood experiences.

In our study, fathers were aware that child attributes such as gender are a factor in their use of physical force, consistent with results from previous studies. Fathers have been reported to play in a more physically involved manner with their sons compared to their daughters (McMunn et al., 2017) and they are more likely to apply physical means of discipline to their sons (Scott & Pinderhughes, 2019), who are also more likely to misbehave than girls (Gulenc et al., 2018). This was reflected in our interview data. For example, father H reported that he had previously hit his nephews when he was frustrated but that he would not resort to physical punishment when disciplining a girl, including his daughter. However, the present findings should not be inappropriately generalised since the literature suggests that a parent’s pattern of discipline may undergo changes during the child’s development. For instance, a U.S. study with a non-abusive, representative sample of parents found that a tendency for physical discipline gave way to more verbal forms of disciplining as children grew older (Jackson et al., 1999).

The current research set out with a position that child maltreatment should include all forms of abuse and neglect which pose risks to children’s well-being; this was clearly communicated in interviews with the fathers in the study. Nevertheless, relevant experiences or incidents that were shared by the fathers in the sample clearly pivoted towards physical punishment as a distinct problematic behaviour during parenting. This may have been a characteristic of the current sample, yet the evidence above linking fathers and boys with physical punishment, suggests this might relate more broadly to a particular issue for parenting in fathers. Further research to pursue the link is warranted, as it may also lead to exploring tailored support for fathers.

Our earlier work with mothers found that mothers’ parenting behaviour was also affected by stress and frustration (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2017). However, the mothers in the study were determined to avoid the use of authoritarian parenting, instead acting in accordance with their parenting ideals. Their aversion to physical punishment was reinforced by a) their belief that rash and reactive behaviour would damage their children’s contentment and respect for their mother; and b) fear that such behaviour would be judged by others as poor parenting (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2017). Such resistance in the face of stress and frustration was not identified in the current analysis with fathers. Instead, the participants recognised their spouses’ greater parental authority, and waived (perhaps reluctantly) their own authority and autonomy to apply their ideals and beliefs as parents. We argue that a sense of incompetence and acceptance of a secondary caregiving role are the pivotal concerns for fathers. The men’s acknowledgment of their subordinate role and their focus on their own (in)competence may lessen their resilience towards maladaptive parenting behaviour, or at least make them more vulnerable at stressful moments of parenting. While further research into parents’ coping mechanisms to manage stress is warranted, the potential qualitative gender difference may hold a key to understanding why the vast majority of maltreatment cases in Japan are perpetrated by fathers or male family members (Japan Police Agency, 2020).

Our analysis identified that fathers felt distressed when their children cried. Excessive crying is a known cause for much stress to parents globally, with studies showing child crying may be an indication of poor parent-child relationship, developmental problems in the child, parental depression or child maltreatment (Korja et al., 2014; Long et al., 2018). In our data, fathers remarked that they felt acute and high levels of stress in response to their children crying, and that their desperation to quieten the child could prompt them to give in to impulsive behaviour, including actions which constitute maltreatment. Fathers’ sensitivity to their crying children seemed to be heightened by their fear of disturbing and receiving complaints from their neighbours and of being seen as an inadequate parent in public. These anxieties echo findings from our earlier research into Japanese mothers (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2017). We would describe such fear as one of social persecution and shame or embarrassment, which have long been described as occupying a central role in Japanese culture. While fear of public shame is shared universally across cultures (Lewis, 1995), it has been suggested that it could be experienced more intensely by Japanese persons when compared to people from Western countries (Furukawa et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2019). This may partially explain why the fathers in our sample felt particularly stressed when their child cried in public. The participants felt ill-equipped to handle day-to-day parenting, and were likely pessimistic about their ability to soothe their children when necessary. Since they feared being exposed as incompetent parents, such challenging moments of parenting were particularly stressful to them.

Limitations and Future Directions

Four main limitations relating to interview structure, recruitment, data gathering and data analysis, respectively, should be pointed out. First, the current research was designed as a comparison study of a previous investigation with middle-class mothers in Japan. As a result, the interviews were somewhat restricted in their structure, particularly around the key aim of studying what fathers considered risks for maltreatment based on their parenting experiences and reflections. In particular, a relatively direct question asked about fathers’ anxiety in the interview. It is possible that the question played a role in informing Category, “3. Unexplainable anxiety of bringing up a child in the analysis”. The question was intended to help fathers feel reassured about speaking of their parenting experiences, including those that may be more difficult to raise without a prompt. However, it is possible that this prompt made an impact on participants’ choice of remarks in the interview. Given the scarcity of previous research with fathers, it is possible that a more broadly constructed interview guide would have been effective in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of fathers’ experiences. Second, the snowballing recruitment may have introduced a sampling bias in recruiting like-minded fathers, specifically those who were receptive to connecting with other fathers and open to accepting the support offered at a midwifery clinic. Since some of the participants were mutually acquainted, it is possible that they may have communicated about the study, which might have led to cross contamination of data. Potentially, this may have also been a factor in reaching data saturation at 11 participants, a relatively small sample size, even for a qualitative study. Third, while the author who conducted the interviews (Y.H.) is an experienced qualitative researcher, it is possible that her presence motivated participants to consider social acceptability as a factor in their responses. Given that many participants regarded their wives as their children’s primary caregivers, the interviewer’s gender may have coloured how participants presented their own role. Social acceptability may also partially account for the difference between the parenting ideal participants espoused and the instances of maltreatment they reported. The potential influence of social desirability could also be relevant for verification of participation eligibility, since this relied on self-reports by participants. We as the research team did our best to provide a safe space for our participants, in which to disclose and confirm their eligibility, and to speak openly about their experiences in the study; we trust our participants and are grateful to their contribution to our research. However, there is the possibility that some of the participants in the study felt unable to disclose relevant information regarding the eligibility criteria—such as information regarding their own health, or that of their child’s or their development, or experience relating to maltreatment—due to social desirability factors. Due to the snowballing recruitment, some participants may have felt concerned that their network was known to the research team; combined with pressures from social desirability factors, this may have introduced additional barrier in disclosing relevant information. Given the reliance on self-report for verification of eligibility, it is also possible that some participants were simply unaware of some of their information concerning eligibility criteria. Fourth, researcher subjectivity (Braun & Clarke, 2019) may have influenced the analysis. The two authors who conducted the preliminary analysis (Y.H. & K.K.) and the fourth author, who contributed to the analysis (M.R.), were mothers. It is possible that their personal experiences of parenting influenced how participants’ remarks were interpreted.

Future research may involve disentangling fathers’ sense of incompetence as described in the present paper from a more objective assessment of their competence as parents. Doing so would allow researchers to identify fathers’ specific needs, and to find effective means of support. Such support may include providing fathers with a safe platform to discuss and understand their parental anxieties, thus boosting their self-efficacy appropriately. In our recent work, we have created a series of leaflets featuring short comics based on our research findings on maternal anxieties (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2019). Interviews with a community sample of mothers, fathers and grandparents suggested that such a format could reassure caregivers that they are not alone in feeling anxious. The interviewees also commented that the leaflets prompted a realisation in them that raising children required mutual support among family members (Hososaka & Kayashima, 2019). We anticipate that similar leaflets specifically addressing paternal experiences may help to empower fathers. Given the complexities in fathers’ parenting experiences which were extracted from the current analysis, there is a need for further research exploring whether such an approach would be acceptable to fathers.

Future work could also explore therapeutic applications of the present findings. Parental awareness and reflections are highly relevant and actively employed in evidence-based intervention programmes such as Trust-Based Relational Intervention (Purvis et al., 2013), video interaction guidance (VIG) therapy (Kennedy et al., 2010), circle of security (Hoffman et al., 2006) or psychotherapeutic approaches (Whitefield & Midgley, 2015). The present findings signal a need for fathers to be more actively included in such programmes. An effective starting point may involve creating a safe environment for fathers to voice their views and to share and reflect on their experiences in co-creating programmes with fellow fathers. This may also lead to insights into the inclusiveness of currently available programmes. As a result, these could be adapted to better suit parents on a spectrum of gender identification or on other dimensions such as culture or race to improve uptake as well as programme efficacy.

Conclusion

Child maltreatment remains a significant issue in Japan and globally. The phenomenon does not occur in isolation but as part of a complex interplay between the actions and mental states of children and their caregivers. The present study highlights the role which fathers attribute to their own anxieties, social and cultural influences, and child characteristics. Their perspectives suggest that perceived parenting incompetence paired with stressful situations such as public embarrassment over a crying child, may form a fertile backdrop for maltreatment. Targeted support aimed at bolstering parenting confidence and increasing paternal caregiving involvement may help fathers to put into practice their ideal of engaged, nurturing parenting.

References

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Ayers, S., Bond, R., Webb, R., Miller, P., & Bateson, K. (2019). Perinatal mental health and risk of child maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104172

Baba, K. (2015). Child abuse and neglect: A concept analysis. Nihon Josan Gakkaishi (Japanese Journal of Midwifery), 29(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.3418/jjam.29.207

Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Novel insights into patients’ life-worlds: The value of qualitative research. Lancet Psychiatry, 6, 720–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30296-2

Camilo, C., Garrido, M. V., & Calheiros, M. M. (2020). The social information processing model in child physical abuse and neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108, 104666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104666

Carcary, M. (2009). The research audit trial—Enhancing trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 7(1), 11–24

Carlson, G. A., & Klein, D. N. (2014). How to understand divergent views on bipolar disorder in youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 529–551. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153702

Children’s Bureau. (2019). Child maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2018.pdf

Chugoku Shimbun Digital. (2020). Number of reported abuse cases in Hiroshima prefecture reaches 59 in 2019, the highest recorded number [Jidou Gyakutai Tekihatsu Saita no 59 ken, Hiroshima ken-nai 19 nen]. https://www.chugoku-np.co.jp/local/news/article.php?comment_id=641268&comment_sub_id=0&category_id=112

Chung, G., Phillips, J., Jensen, T. M., & Lanier, P. (2020). Parental involvement and adolescents’ academic achievement: Latent profiles of mother and father warmth as a moderating influence. Family Process, 59(2), 772–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12450

Coleman, D. L., Dodge, K. A., & Campbell, S. K. (2010). Where and how to draw the line between reasonable corporal punishment and abuse. Law and Contemporary Problems, 73(2), 107–166

da Cruz Benetti, S. P., & Roopnarine, J. L. (2006). Paternal involvement with school-aged children in Brazilian families: Association with childhood competence. Sex Roles, 55(9–10), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9122-z

Dollard, J., Doob, C. W., Miller, N. E., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. Yale University Press

Egeland, J. A. (1988). A genetic study of manic-depressive disorder among the old order Amish of Pennsylvania. Pharmacopsychiatry, 21(2), 74–75. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-101465

Font, S. A., & Maguire-Jack, K. (2020). It’s not “just poverty”: Educational, social, and economic functioning among young adults exposed to childhood neglect, abuse, and poverty. Child Abuse & Neglect, 101, 104356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104356

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)61442-4

Furukawa, E., Tangney, J., & Higashibara, F. (2012). Cross-cultural continuities and discontinuities in shame, guilt, and pride: A study of children residing in Japan, Korea and the USA. Self and Identity, 11(1), 90–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2010.512748

Gaertner, B. M., Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., & Greving, K. A. (2007). Parental childrearing attitudes as correlates of father involvement during infancy. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 69(4), 962–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00424

Gallegos, M. I., Jacobvitz, D. B., Sasaki, T., & Hazen, N. L. (2019). Parents’ perceptions of their spouses’ parenting and infant temperament as predictors of parenting and coparenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(5), 542–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000530

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539

Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Groh, A. M., Fearon, R., IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment in the early life course: Meta‐analytic evidence for its role in socioemotional development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(1), 70–76

Gulenc, A., Butler, E., Sarkadi, A., & Hiscock, H. (2018). Paternal psychological distress, parenting, and child behaviour: A population based, cross-sectional study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(6), 892–900. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12607

Hoffman, K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Powell, B. (2006). Changing toddlers’ and preschoolers’ attachment classifications: The circle of security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1017–1026. 2006-22003-004

Hososaka, Y., & Kayashima, K. (2017). Aspects of the boundary between discipline and abuse by mothers raising preschool age children. Japanese Journal of Nursing [Nihon Kango Kagakki Shi], 37, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5630/jans.37.1

Hososaka, Y., & Kayashima, K. (2019). Utilizing 4-frame comics in child-rearing support~Focusing on the boundary between discipline and abuse. Japanese Journal of Maternal Health, 59(4), 896–905.

Hossain, Z., & Roopnarine, J. L. (1994). African-American fathers’ involvement with infants: Relationship to their functioning style, support, education, and income. Infant Behavior and Development, 17(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(94)90053-1

Hossain, Z., Roopnarine, J. L., Masud, J., Muhamed, A. A., Baharudin, R., Abdullah, R., & Juhari, R. (2005). Mothers’ and fathers’ childcare involvement with young children in rural families in Malaysia. International Journal of Psychology, 40(6), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590444000294

Jackson, S., Thompson, R. A., Christiansen, E. H., Colman, R. A., Wyatt, J., Buckendahl, C. W., Wilcox, B. L., & Peterson, R. (1999). Predicting abuse-prone parental attitudes and discipline practices in a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00108-2

Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2020). For parenting that does not involve corporal punishment~ creating a society where everyone supports child rearing. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11920000/minnadekosodate.pdf

Japan Pediatric Society. (2014). A guide to child abuse treatment. http://www.jpeds.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=25

Japan Police Agency. (2020). Juvenile delinquency, child abuse and child sexual harm in 2019. https://www.npa.go.jp/safetylife/syonen/hikou_gyakutai_sakusyu/R1.pdf

Kato, S., & Fujioka, T. (2020). The recognition of boundary for child discipline and child abuse: Following the present situations of disciplinary behaviour in French. Research Bulletin [Kenkyu Kiyou], 66, 137–152

Kennedy, H., Landor, M., & Todd, L. (2010). Video interaction guidance as a method to promote secure attachment. Educational & Child Psychology, 27(3), 59–72

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(3), 251–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4

King, D. C., Abram, K. M., Romero, E. G., Washburn, J. J., Welty, L. J., & Teplin, L. A. (2011). Childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorders among detained youths. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1430–1438. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.004412010

Korja, R., Huhtala, M., Maunu, J., Rautava, P., Haataja, L., Lapinleimu, H., & Lehtonen, L., PIPARI Study Group. (2014). Preterm infant’s early crying associated with child’s behavioral problems and parents’ stress. Pediatrics, 133(2), e339–e345. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1204

Lamb, M. E., & Lewis, C. (2004). The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 272–307). Wiley

Lamb, M. E., & Lewis, C. (2013). In N. J. Cabrera & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.), Father-Child Relationships; Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203101414

Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., Crozier, J., & Kaplow, J. (2002). A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(8), 824–830. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824

Lee, J. Y., Knauer, H. A., Lee, S. J., MacEachern, M. P., & Garfield, C. F. (2018). Father-inclusive perinatal parent education programs: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 142(1), e20180437. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0437

Lee, K. W., Yamashita, A., & Tsumura, M. (2012). The recognition and the actual conditions of discipline and abuse: Based on a questionnaire survey towards parents of preschoolers. Nihon Kaseigaku-Shi [Japanese Journal of Home Economics], 63(637), 379–390

Lengua, L. J. (2008). Anxiousness, frustration and effortful control as moderators of the relation between parenting and adjustment in middle-childhood. Social Development, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00438.x

Lewis, C., & Lamb, M. E. (2006). In R. Budden (Ed.), Father-child relationships and children’s development: A key to durable solutions? Family Law/Jordans

Lewis, M. (1995). Shame: The exposed self. Free Press

Li, C., Jiang, S., Fan, X., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Exploring the impact of marital relationship on the mental health of children: Does parent-child relationship matter? Journal of Health Psychology, 25(10–11), 1669–1680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318769348

Long, J., Powell, C., Bamber, D., Garratt, R., Brown, J., Dyson, S., & James-Roberts, I. S. (2018). Development of materials to support parents whose babies cry excessively: Findings and health service implications. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 19(4), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423617000779

Lünnemann, M. K. M., Van der Horst, F. C. P., Prinzie, P., Luijk, M. P. C. M., & Steketee, M. (2019). The intergenerational impact of trauma and family violence on parents and their children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104134

McMunn, A., Martin, P., Kelly, Y., & Sacker, A. (2017). Fathers’ involvement: Correlates and consequences for child socioemotional behavior in the United Kingdom. Journal of Family Issues, 38(8), 1109–1131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15622415

Meeussen, L., & Van Laar, C. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02113

Mitchell, S. J., See, H. M., Tarkow, A. K. H., Cabrera, N., McFadden, K. E., & Shannon, J. D. (2007). Conducting studies with fathers: Challenges and opportunities. Applied Developmental Science, 11(4), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690701762159

Ninomi, K., Shinohara, Y., Fujita, M., Tsuda, A., Nishimura, M., & Seki, H. (2004). A study on the factors concerning the recognition of child abuse and neglect using multiple logistic regression analysis. Pediatric Welfare Research [Shouni Hoken Kenkyuu], 63(634), 436–441

Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers–recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 55(11), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12280

Pidgeon, A. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2009). Attributions, parental anger and risk of maltreatment. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development, 2(1), 57–69

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., Dansereau, D. F., & Parris, S. R. (2013). Trust-based relational intervention (TBRI): A systemic approach to complex developmental trauma. Child & Youth Services, 34(4), 360–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935x.2013.859906

Rivera, E. A., Sullivan, C. M., Zeoli, A. M., & Bybee, D. (2018). A longitudinal examination of mothers’ depression and PTSD symptoms as impacted by partner-abusive men’s harm to their children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(18), 2779–2801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516629391

Rodriguez, C. M., Russa, M. B., & Kircher, J. C. (2015). Analog assessment of frustration tolerance: Association with self-reported child abuse risk and physiological reactivity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.017

Rodriguez, C. M., Baker, L. R., Pu, D. F., & Tucker, M. C. (2017). Predicting parent-child aggression risk in mothers and fathers: Role of emotion regulation and frustration tolerance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2529–2538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0764-y

Roopnarine, J. L., Fouts, H. N., Lamb, M. E., & Lewis-Elligan, T. Y. (2005). Mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors toward their 3- to 4-month-old infants in lower, middle, and upper socioeconomic African American families. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.723

Roopnarine, J. L., Krishnakumar, A., Metindogan, A., & Evans, M. (2006). Links between parenting styles, parent–child academic interaction, parent–school interaction, and early academic skills and social behaviors in young children of English-speaking Caribbean immigrants. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(2), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.007

Roopnarine, J., & Yildirim, E. D. (2019). Fathering in cultural contexts: Developmental and clinical issues (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315536170

Scott, J. C., & Pinderhughes, E. E. (2019). Distinguishing between demographic and contextual factors linked to early childhood physical discipline and physical maltreatment among black families. Child Abuse & Neglect, 94, 104020. S0145-2134(19)30182-6.

Sugimoto, M., & Yokoyama, M. (2015). Chichi oya no gyakutaiteki kosodate ni kanrensuru youin no kentou [The factors associated with maltreating parenting behaviors of fathers with young children]. Shouni Hoken Kenkyu [The Journal of Child Health], 74(6), 922–929

Thomas, R., Deighton, R., Mizuno, M., Yamaguchi, S., & Fujii, C. (2019). Shame and self-conscious emotions in Japan and Australia: Evidence for a third shame logic. Culture & Psychology, 26(3), 1354067X1985102–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067x19851024

Ueda, K., Saeki, K., Kawaharada, M., Hirano, M., Izumi, H., & Namikawa, K. (2014). Hokenshi ga toraeru kodomo gyakutai jirei ni okeru chichioya no taijinkankei to koudou no tokusei [Public health nurses’ perspective of interpersonal relationships and behavioural characteristics of fathers who abused their children]. Nihon koushu eisei kango gakkaishi [Japan Journal of Public Health Nursing], 2(1), 2–11

Van der Kooij, I. W., Chotoe-Sanchit, R. K., Moerman, G., Lindauer, R. J. L., Roopnarine, J. R., & Graafsma, T. L. G. (2018). Perceptions of adolescents and caregivers of corporal punishment: A qualitative study among Indo-Caribbean in Suriname. Violence and Victims, 33(4), 686–707. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-16-00222

Van Wert, M., Anreiter, I., Fallon, B. A., & Sokolowski, M.B. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: a transdisciplinary analysis. Gender and the Genome. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470289719826101

Vinjamuri, M. (2016). “It’s so important to talk and talk:” How gay adoptive fathers respond to their children’s encounters with heteronormativity. Fathering, 13(3), 245. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.1303.245

Wang, F., Wang, M., & Xing, X. (2018). Attitudes mediate the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment in China. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 34–43

White Paper on Gender Equality. (2016). Towards accepting diverse work styles and lifestyles. http://www.gender.go.jp/english_contents/about_danjo/whitepaper/pdf/ewp2016.pdf

Whitefield, C., & Midgley, N. (2015). And when you were a child?’: How therapists working with parents alongside individual child psychotherapy bring the past into their work. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 41(3), 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2015.1092678

Wong, J. J., Roubinov, D. S., Gonzales, N. A., Dumka, L. E., & Millsap, R. E. (2013). Father enrolment and participation in a parenting intervention: Personal and contextual predictors. Family Process, 52(3), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12024

Xue, W. L., Shorey, S., Wang, W., & He, H. G. (2018). Fathers’ involvement during pregnancy and childbirth: An integrative literature review. Midwifery, 62, 135–145. S0266-6138(16)30315-1

Yehuda, R., Halligan, S. L., & Grossman, R. (2001). Childhood trauma and risk for PTSD: Relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental PTSD, and cortisol excretion. Development and Psychopathology, 13(3), 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579401003170

Yoon, S., Bellamy, J. L., Kim, W., & Yoon, D. (2018). Father involvement and behavior problems among preadolescents at risk of maltreatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(2), 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0890-6

Zhang, C., Cubbin, C., & Ci, Q. (2016). Parenting stress and mother–child playful interaction: The role of emotional support. Journal of Family Studies, 25(2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1200

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the midwifery clinics for their support with recruitment, the participants for their cooperation and trust in sharing their parenting experiences, and their families for supporting their participation in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17K12320, Tokyo/JAPAN, awarded to Y.H. and K.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article