Abstract

Improving the process through which mental health professionals are trained in evidence-based practices (EBPs) represents an important opportunity for extending the implementation of EBPs in community settings. In this study, we used a qualitative approach to examine the specific training elements that were beneficial to clinicians’ experiences learning an evidence-based intervention. Individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted with mental health professionals completing training in the GenerationPMTO parenting intervention. Data were analyzed using the tenets of thematic analysis. Overall, participants reported positive experiences in the training and growth in their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in GenerationPMTO. The qualitative findings also suggested seven specific training elements that participants perceived as beneficial: support, role plays, engagement, structure, writing/visuals, working with training families, and experiencing the GenPMTO model. These results are discussed within the context of the existing literature on EBP training and more broadly as they relate to expanding the implementation of evidence-based interventions. We also suggest implications for practice meant to enhance future EBP training efforts.

Highlights

-

Improving how clinicians are trained in evidence-based practices may help support implementation of effective interventions.

-

Clinicians completing a GenerationPMTO training perceived growth in their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in the model.

-

Support, role plays, engagement, structure, writing/visuals, working with training families, and experiencing the model were identified as beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mental health professionals are a critical source of support for children and families struggling with mental, emotional, and behavioral problems. With as many as 4.5 million children in the United States diagnosed with a behavioral disorder in a given year (Ghandour et al. 2019), there is a continued need to ensure that mental health professionals are trained in EBPs so that effective mental health interventions can reach the families who need them (Kazdin 2017). More specifically, EBPs focused on improving parenting outcomes have shown to be successful in treating significant child behavioral problems (e.g., Fossum et al. 2014). Yet, implementing EBPs in community settings is a complex and challenging process. As a result, an important gap exists in applying interventions to real-world settings (Connor-Smith and Weisz 2003). More research is needed to identify actionable strategies that can bridge this research to practice gap.

The GenerationPMTO (GenPMTO) parenting intervention, formerly known as Parent Management Training - the Oregon Model (PMTOTM) has shown to be effective in improving child behavioral problems (Dishion et al. 2016; Forgatch and Gewirtz 2017). With over 50 years of research, the success of this model in supporting parents to improve parenting skills and overall child outcomes has led to an increasing demand for GenPMTO training and implementation (Forgatch and DeGarmo 2011). Through sustained and intentional efforts (Forgatch et al. 2013), GenPMTO has been effectively implemented across multiple contexts in the United States and around the world (see Forgatch and Gewirtz 2017). Research has shown that receiving training in GenPMTO improves competent adherence to the model and that higher levels of competent adherence are associated with better outcomes for families (Forgatch and DeGarmo 2011; Forgatch et al. 2004). Overall, there is strong evidence that GenPMTO training is effective. However, less attention has been focused on the successful elements of the GenPMTO training process. The aim of the present study is to use qualitative data from clinicians who completed a GenPMTO training to identify beneficial training elements.

Training in Evidence-Based Practices

A well-known gap exists between developing EBPs and implementing them in community mental health settings as standard practice (Proctor et al. 2009). Yet, providing clinicians with EBP training is recognized as an important strategy in integrating EBPs into real-world practice (Powell et al. 2012). Studies have found that the combination of the quality of training, component specific supervision, and tangible resources are effective methods in transforming dissemination and implementation efforts (Beidas and Kendall 2010; Herschell et al. 2010). Specifically, clinician attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in implementation efforts are more likely to improve following training and supervision in an EBP (Beidas and Kendall 2010; Herschell et al. 2010).

Despite the various literature supporting the importance of using EBPs to improve clinical practice, an important gap still exists in identifying training elements that lead to effective program outcomes (Akin et al. 2014; Hoagwood and Olin 2002). Current training methods cover a variety of styles, including passive and active approaches to workshop preparation (Cross et al. 2007, Yorks et al. 2003). Methods such as lectures, reviewing manuals, and non-interactive activities are widely used in the field despite findings that suggest limited behavior change (El-Tannir 2002). While some research has shown that active training strategies (e.g., modeling, practice opportunities, role plays) are effective in facilitating skill development and implementation for clinicians (Clark 2019; Cross et al. 2007), more research is needed to continue identifying beneficial elements of training in EBPs.

Clinicians and Evidence-Based Practice Implementation

It is pivotal to recognize the role of clinicians when attempting to understand why EBPs are successfully—or not successfully—implemented in real-world contexts. One potential factor influencing implementation is clinician level of comfort and support in learning the intervention (Gallo and Barlow 2012). Clinicians have reported that evidence-based protocols are often too rigid, and require many steps, which reduces the chance of further implementation (Nelson et al. 2006). This can be exacerbated when clinicians have limited evidence-based knowledge or clinical experience (Aarons 2004). Therefore, to increase the likelihood of implementation, it is important for clinicians to be knowledgeable about the intervention and hold positive attitudes (Nelson and Steele 2007). Research integrating the perspectives of clinicians learning an EBP can help to make a positive contribution to the literature in this area.

An Implementation Science Framework

Although there has been some progress in the broader literature to identify practices that support EBP training, it is important to take steps to advance this work more systematically (Davies et al. 2010). This objective is embedded within an implementation science paradigm. Accordingly, implementation research is the systematic study of “strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions into clinical and community settings” to improve client outcomes (National Institutes of Health [NIH] 2019, Implementation Research section).

Integrating EBPs into community practice settings involves several different processes, and scholars have found it useful to conceptualize these activities according to different stages of implementation (Chamberlain et al. 2011). Specifically, embedding EBPs into community settings has been described according to eight different stages that consist of important pre-implementation, implementation, and sustainability activities. Stage 4, which takes place during the implementation phase, includes activities associated with clinical training (Chamberlain et al 2011). Therefore, advancing scholarship on beneficial clinical training elements stands to make an important contribution to the implementation science agenda.

Moreover, researchers have highlighted the critical ways in which qualitative approaches can contribute toward advancing implementation science (Hamilton and Finley 2019). Qualitative approaches are valuable for generating in-depth data to explore and better understand how individuals experience a given phenomenon (Creswell 2009). They are also well-suited for informing practice (Hamilton and Finley 2019). In implementation science research, qualitative methods can provide a well-suited and rigorous approach for addressing questions of how and why (Hamilton and Finley 2019), which can be useful for discerning the ways in which specific EBP training elements are perceived by clinicians.

The Current Study

There is a shortage of empirical work exploring the experiences of clinicians receiving EBP training, especially research identifying the specific elements that clinicians perceive as beneficial to the EBP training process. This qualitative study sought to advance scholarship in this area via two related research aims. First, we examined participants’ experiences receiving training in the evidence-based GenPMTO intervention. Guided by the empirical literature on therapist training (Beidas and Kendall 2010; Herschell et al. 2010), we focused particularly on participant experiences in connection to their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in relation to GenPMTO. Second, to address the gap in knowledge about training elements supporting effective program outcomes (e.g., Akin et al. 2014; Hoagwood and Olin 2002), we sought to learn which specific aspects of the GenPMTO training were perceived as beneficial by clinicians. Achieving these aims can make an important contribution to the implementation science literature by identifying potential methods that could help improve EBP training for mental health professionals, thereby advancing implementation of EBPs in community settings.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from a PMTOFootnote 1 training delivered to mental health professionals through the public mental health system in a Midwestern state. Participants were eligible for this study if they met the following criteria: (1) currently a community mental health provider, (2) attended weeks one and two of the PMTO training, and (3) agreed to participate in the study. The research team members conducting this study were not eligible to participate in the study and were not included as study participants. Recruitment activities involved verbal descriptions of the study provided by PMTO trainers and email invitations sent out to training participants by research team members. This study was conducted with authorization from the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Institutional Review Board.

Of the 11 training participants meeting eligibility criteria, 10 participated in this study (91% response rate). This included seven females and three males. The sample included eight participants identifying as White/Caucasian and two participants identifying as Black/African American. All participants had a master’s degree in social work. The majority (n = 8) of participants had between one to five years of experience in the mental health field; the remainder (n = 2) reported between six months to one year of experience. Four participants reported that the PMTO training was the first evidence-based training they had attended, four had attended one prior evidence-based intervention training, and two had attended 2–5 prior trainings. Participants reported multiple reasons for attending the training: interest in learning an evidence-based practice (n = 7), a desire to effectively help more families (n = 6), to advance their careers (n = 4), because it was recommended by their agency (n = 2), and to become a better parent (n = 1).

Procedures

Training Context

The focal EBP in this study is PMTO, a parenting intervention that has been implemented through the public mental health system in Michigan for over 15 years; during that time, hundreds of practitioners have been trained in the model (Forgatch and Gewirtz 2017). The PMTO intervention has five core components: (a) skill encouragement, (b) limit setting, (c) problem solving, (d) monitoring, and (e) positive involvement. Delivery of the intervention is also characterized by active teaching behaviors, role playing, and specific process skills that must be administered adeptly by the practitioner in order to maintain fidelity to the model (Forgatch and Gewirtz 2017; Knutson et al. 2019). Taken together, these features make PMTO a strong candidate for examining training processes. The typical GenPMTO training process includes attending workshops and coaching, didactic presentations accompanied by informational material, modeling and role playing, conducting simulated and actual family sessions, making video recordings, and reviewing sessions and receiving feedback from coaches (Forgatch and DeGarmo 2011). Training is normally facilitated by two to four co-trainers who provide assistance to one another and share in the training responsibilities.

For this study, we investigated a typical implementation of the GenPMTO training process: a training for community mental health providers who would be delivering the individual family model of GenPMTO, referred to in the Michigan implementation context as PMTO. The training took place as part of a multi-phase certification process that ensures providers are able to practice with a rigorous level of competent adherence to the model. Prior to the training, clinicians received an introduction to the PMTO model (e.g., through a 2-day workshop). Then, the main training process consisted of participating in one (4-day) week of training, a one-month break to assimilate information and begin implementing PMTO with a training family, and then participating in the second (4-day) week of training. All participants in this study attended the same training with the same set of four PMTO co-trainers. In accordance with our research questions, the focus of this study was on participants’ experiences during this training process. Due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Michigan, the second week of training was delivered online. The online portion of training retained all core practices characteristic of GenPMTO training but with a modified delivery format (e.g., meeting using Zoom technology, using virtual break-out rooms to facilitate small group role-plays, employing the screen sharing function to present visual information). Following this training, clinicians would be eligible to continue working toward certification in the PMTO model by practicing PMTO while receiving coaching feedback, attending supplemental trainings, and receiving satisfactory fidelity scores based on recordings of their PMTO sessions.

Research Team

This research took place as part of an informal public-academic partnership between the state-level purveyors of PMTO in Michigan and a research team affiliated with a university in the state. Such partnerships represent an important means for reducing the gap between research and practice by enabling researchers and mental health service providers to collaborate in conducting relevant and rigorous research (Palinkas et al. 2015). As part of this partnership, research team members support PMTO in systematically monitoring and evaluating ongoing dissemination efforts while PMTO collaborators share training opportunities with the team.

In this study, all six members of the research team were affiliated with a couple and family therapy doctoral program at a research-intensive university. The doctoral program places particular emphasis on research and training in evidence-based interventions. The research team had a diverse composition in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, age, national origin, experience in the mental health field, and other factors. All research team members attended the same PMTO training alongside the participants in this study; five researchers attended as trainees while the senior author participated as a co-trainer. This form of “prolonged engagement” with the PMTO training allowed the team to develop a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of interest (Lincoln and Guba 1985). Together, the diversity of the research team and awareness of the PMTO training context added valuable richness to this study.

Data Collection

Five members of the research team collected data through individual interviews. Out of awareness that participants might not feel comfortable sharing their honest experiences with a member of the training team, the senior author did not conduct interviews. The senior author was also blinded to the individual identities of participants during the interview process, so that she could not link the interview responses back to a particular training participant. Participants were made aware that their identity would not be tied to any of the answers they provided, an additional safeguard to protect participants and enhance the validity of the data.

A semi-structured interview guide was used to standardize the process, which combined general questions about the training (e.g., “Tell me about your experience in the PMTO training”) and probing questions that targeted more detailed information (e.g., “What training methods influenced your feelings/attitude about PMTO?”). The interview guide is provided as Supplemental File A. Interviews were conducted online using Zoom software over a two-week period directly following the final week of PMTO training. Interviews lasted an average of 47 min. All interviews were audio recorded via the integrated Zoom recording function and then transcribed verbatim by the interviewer in preparation for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 2020 (VERBI Software 2019) and following the tenets of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). In Phase 1, the five researchers involved in data collection familiarized themselves with the data through conducting and transcribing the interviews; all six members of the research team then engaged in reading the interview transcripts. The research team then began generating initial codes (Phase 2) by carefully examining each transcript, identifying meaningful segments of text, and labeling the raw data with descriptive codes. Our codes were generated using an integration of deductive and inductive coding (Forman and Damschroder 2007). Based on our first study aim, we generated a priori codes for participant attitudes, knowledge, and confidence related to the PMTO training, and used these deductive codes to identify relevant data for examining participants’ experiences in each of these areas (Braun and Clarke 2006; Forman and Damschroder 2007). We also utilized inductive coding to generate themes from the data related to beneficial PMTO training elements described by participants and as a means to refine and revise the deductive codes as needed (Forman and Damschroder 2007). We used memos during this process to record our thoughts on the data and capture hypotheses about emerging themes. Three of the six research team members coded each transcript. The triads varied by transcript and included (a) the researcher who had conducted that interview, (b) another research team member, and (c) the senior author. All six of the team members took part in the coding. In Phase 3, all research team members began identifying themes in the data. This took place as every researcher read through each transcript and started to recognize higher-order patterns of meaning related to the focal research questions. We used thematic maps to facilitate this phase. During this process of reviewing every transcript, the research team determined that sufficient saturation had been achieved because the addition of new data was not meaningfully extending our understanding of the identified themes (Guest et al. 2006). Next, we reviewed the themes (Phase 4) and proceeded with defining and naming them (Phase 5). Following Braun and Clarke (2006), it was important for the different themes to be distinctive, but data extracts may fit into—and should be coded for—multiple different themes. During regular research team meetings, we discussed our evolving perceptions of the data until we arrived at a codebook describing a set of candidate themes and sub-themes. This stage in the project corresponded to the end of the academic semester and one research team member transitioned to other responsibilities, ending involvement with the project. The remaining research team members then returned to the data to re-code each transcript using the candidate set of themes and sub-themes. Each transcript was re-coded by two research team members. Different pairs were assigned across the different transcripts and all five remaining team members participated in the re-coding. Discrepancies between coders were discussed until consensus was achieved. Once this was completed, we refined our final set of themes and subthemes according to those which had been supported within the majority of transcripts. The closing stage (Phase 6) of data analysis took place as we wrote out the study findings and rendered the themes and subthemes into narrative form (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness refers to standards for ensuring quality and rigor in qualitative research (Morrow 2005). We employed several strategies in this study to establish trustworthiness of the findings. As recommended by Hamilton and Finley (2019), research team members used a semi-structured interview guide to help standardize the data collection process during the individual interviews. Data analysis was carried out by multiple research team members, with a minimum of three researchers coding each transcript. Use of multiple coders is valuable in qualitative research for stimulating competing explanations and multiple interpretations of the data that lead to coding refinements and ultimately more thorough analyses (Barbour 2001). Team meetings were held weekly while data analysis took place in order to cross-check codes, triangulate understanding of the data, and monitor for researcher bias. Qualitative scholars have suggested that engaging in this type of reflexive process as a team can support the quality and trustworthiness of qualitative research (Barry et al. 1999). Toward the end of data analysis, we performed an additional credibility check (Elliott et al. 1999), where all transcripts were consensus coded by two researchers to ensure the identified themes were corroborated by the majority of participants. Additional efforts to ensure credibility included prolonged engagement with participants during the PMTO training (Lincoln and Guba 1985; Morrow 2005), integrating multiple participant quotations into the findings section to ground our findings in examples from the data (Elliott et al. 1999), and accompanying each quotation with a participant number to demonstrate the representativeness of the data. The rigor of this work is further supported by attention to the training and experience of the research team in qualitative methods (Hamilton and Finley 2019). Specifically, each member of the research team has completed a graduate level qualitative research methods course, and the senior author has established expertise in conducting qualitative research.

Findings

Study findings suggested a high level of satisfaction with the PMTO training and that participants perceived growth in their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in the model. The findings also implicated seven specific elements that were perceived as fostering a positive learning environment during the PMTO training.

Aim 1: Overall Training Experience

Participants unanimously reported highly positive overall perceptions of the PMTO training. For instance, when asked in the first interview question to “tell me about your experience in the PMTO training,” participants responded: “I felt like I had a really great experience” (Participant #3), “For me it was very positive” (Participant #4), “I thought it was really good” (Participant #9), and “My experience has been great” (Participant #10). Participant #7 described it as “probably the best training I’ve been to maybe ever.” And participant #6 expressed, “I have been to a lot of trainings in my time…and this training was the best training I have ever gone to.”

Attitudes

After completing the training, participants expressed favorable attitudes toward PMTO. Participant #8 disclosed, “After the first week, I wanted to solely be a PMTO clinician.” Likewise, Participant #2 explained, “I bought in, I did. Yeah, I wouldn’t call it fanaticism, but I really did buy in!” Part of this buy-in may have been that participants perceived PMTO as compatible with their views of therapy. As Participant #6 described, “Working through parents to better the children’s lives and the whole family…that is what I want to do as a clinician.”

Participants described arriving at the training with different mindsets, ranging from excitement, to being neutral, to feeling wary after having been warned about the amount of work it would be. Yet, by the end of training, participants expressed similar beliefs that the model would be valuable for families. For example, Participant #3 reflected, “To be honest, I wasn’t really sure about how things were gonna go with it…trying to learn how it would fit with me and the work I do with my families. And so, it ended up going really well and it was so relatable to the work I do.” Participants described the positive impact of watching video interviews with caregivers who had experienced the model and seeing positive results when practicing PMTO with colleagues, family members, or clients. Participant #2 remarked, “I was like, this can’t be true, right? This can’t work like this. And then it did.” Participants also described being moved by the commitment and authenticity of the trainers. Overall, Participant #9 concluded, “I feel like I’m going to be using everything I learned for the rest of my career.”

Knowledge

Participants also reported satisfactory outcomes for PMTO knowledge after completing the training. Participant #8 described her level of knowledge as “a heck of a lot more than I had before,” and Participant #10 echoed “way higher than it was before.” Participant #3 commented “I feel like it enhanced my knowledge because I wasn’t very aware, necessarily, of the process of it and the model itself.” This person went on to explain, “They did a really great job of ensuring that we were all understanding the process, understanding what the steps were, and if we had questions or if we weren’t getting it we just continued, you know, to work on it.” At the same time, participants acknowledged they still had more to learn about the model. As Participant #8 explained, “I barely knew what PMTO stood for before I started. And with that, I think it was a great level of knowledge…Do I feel uncertain with some of my skills? Yeah. But I also feel more open in using those tools than I did before.” Importantly, participants also described feeling certain their knowledge would continue to increase with the resources and support they were receiving. Participant #4 explained, “I would say on a scale of 0–100% with 0 before the training, I would say that I am probably closer to about 65–70% in my knowledge base and knowing that 70–100% I have access to resources and people…to help me when I do struggle.” Similarly, Participant #6 remarked, “If I took a test right now I would probably like get an 80 [percent]… there is just so much information and so much good things in there that I am positive that I have not remembered it all and that as I utilize it my knowledge will just increase.”

Confidence

Finally, participants reported they had gained confidence in delivering PMTO to families. Participant #3 expressed, “I feel like I’m definitely at a level of having more confidence with using it” and went on to explain, “I’ve only had two sessions with [client] so far, but I feel like as time goes on, I’m getting more confident with it.” While participants described overall positive trajectories in confidence resulting from the training, there was variation in the current level of confidence reported by participants. For instance, a few participants reported high levels of confidence. Participant #2 quantified, “If I was on a Likert scale, zero to ten, zero being not confident, ten being very confident, I would put myself at about a nine.” However, it was more common for participants to report modest levels of confidence following the training. Participant #1 expressed, “I’m feeling somewhat confident. I think it is still going to take a lot to be able to build that.” Participant #8 explained, “I would say my confidence level is at maybe like a 60–70%. But that is where I am supposed to be.” There was an understanding that it was normal and acceptable to still feel a bit unsure at this point and participants expected that their confidence would increase as they gained additional experience and support delivering the intervention. Participant #4 explained, “I actually feel very confident because I know that my approach with the families can be ‘I am still learning this, you are learning this, I am going to mess up, you are going to mess up, we all are going to mess up.’” Participant #7 shared, “The fact that I know that there’s more resources and support coming makes me a lot more confident.”

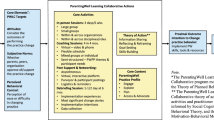

Aim 2: Training Elements Perceived as Beneficial

Study findings implicated specific training elements that were perceived to have positively influenced practitioners’ experiences learning PMTO. To be included, each theme had to be reported as beneficial by the majority of participants. Each theme is intended to be distinct, although some overlap across themes and subthemes is inherent due to the interconnected and mutually reinforcing nature of the training elements. Seven key training elements were identified. The elements are summarized in Table 1 and described below. Please note that the ordering of the elements in the findings section is not meant to imply a ranking of influence or importance.

Support

The first central theme reflected in the data was the high level of support participants perceived throughout the training. This strong sense of support provided a foundation that participants described as influential to enhancing their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence with the intervention. This sense of support also served as a critical context that helped participants feel safe to engage in training activities. For example, as Participant #3 explained, “Role plays. When we started doing them it just kinda came natural after a while. I mean, it was such a supportive [environment], I didn’t feel pressured. I felt, like, supported to do them.”

Sources of Support

Participants described receiving support from several different sources during the training, resulting in a high level of camaraderie within the group.

Support from Trainers

PMTO trainers are the individuals who lead the training workshops. Participants described PMTO trainers as an important source of support. As Participant #4 shared, “I think they do a really good job of letting you know that you’re supported and they want to set you up for success.” The trainers were described as “really well-versed and strong” in the model, “fun,” and “easy to approach.” Participants felt supported, for instance, in the way the trainers provided encouragement, normalized the anxiety that accompanies learning new things, established a sense of community among the training group, and led by example.

Support from Fellow Trainees

Other participants in the training also served as an important source of support. As Participant #3 shared, “We’re all in this together and it’s like a team effort.” Similarly, Participant #7 explained, “We were, like, all a supportive group. You know, like a supportive family almost.” In this way, fellow trainees were perceived as active in co-creating a supportive context where everyone worked together, demonstrated respect for different backgrounds and therapy styles, and were open to learning from one another.

Support from Coaches

PMTO coaches are the individuals who provide ongoing feedback and consultation to clinicians to foster skill development and competent adherence to the GenPMTO model. PMTO coaching starts during training and continues thereafter. Participants described the PMTO coaches as another important source of support. Participants expressed appreciation that a coach would be available to answer questions and provide support as they moved forward in their training and certification process. As Participant #9 shared, “Having a coach by your side is…huge.” They described the coaching process as helpful and rewarding. Participant #4 recalled, “I thought [my session] was a hot mess, but it felt good to get coaching. You want to get it again because it is so positive and they say all these good things about you.”

Supportive Training Elements

In addition to describing sources of support, participants described a number of different training elements that were instrumental in helping them feel supported.

Strengths-Based Focus

The strengths-based focus of the training was evidenced in the data as a central feature that fostered a supportive environment. Participants described how the training was characterized by positivity, with an emphasis on strengths and successes instead of deficits. Participant #10 explained, “It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, go try to ride the bike by yourself, and then I will show you how you messed up and how to ride it.’ They were like, ‘…We’ll show you what it looks like to do it right, and then we’ll help you troubleshoot it along the way in a very strength-based manner.’” Participants also expressed appreciating the encouragement they received as part of the training. Participant #6 shared, “Right from the beginning…getting encouragement and getting praise set the grounds for me wanting to be there and excited to go the next day.” As exemplified in this statement, participants perceived the strength-based focus as influential in fostering their buy-in to the training as well as the PMTO model.

Receiving Resources/Materials

Participants also expressed feeling supported by the tangible materials and access to resources they received from the training, such as a detailed intervention manual and access to an online portal with relevant resources. As Participant #6 expressed, “I like having step-by-step things in front of me. Like if I lose my place or [am] not sure what to do with the family next, I have that to look in.” Participants also received a number of resources to support them in providing GenPMTO to families, such as a dry erase board, visual cues for reinforcing key concepts (e.g., magnets or note cards), and small incentives to use with families to provide positive reinforcement (e.g., wrist bands, stickers). For example, Participant #4 appreciated, “Anything that they gave us that was something that we could take with us to the family’s home and share as a reminder with them.”

Responsiveness of Training

The data indicated that another way in which participants felt supported was via the responsiveness of the training: They felt their questions were addressed and that they received support when needed. For example, Participant #6 explained, “It was like, everything I had thought about, they had an answer for if I had just waited a couple of minutes.” Participants also described situations in which they were confused or unsure how to implement part of the model and how they received support to successfully troubleshoot these issues. Overall, as Participant #7 noted, the trainers “were very sensitive to any concerns that anybody raised.”

Ongoing Commitment

Finally, participants expressed appreciation for the way in which the support and resources made available through the training continued even after the workshop-based portion was completed. This included continued access to supportive people (e.g., coaches, peer cohort) and tangible resources (e.g., intervention manual, portal) as they moved forward using the model. As Participant #3 explained, “We all really grew close together and I feel like we could collaborate later if need be. …Knowing that if I’m stumbling, I have like support for the future.” Similarly, Participant #8 reflected, “They set you up for that success, they really do. They really break down every single detail that you might need to know. Then on top of it, they give you a coach afterwards.” She went on to conclude: “I think it’s cool because PMTO does never leave you at that point.”

Role Plays

The second influential training element identified in this study was role plays. Role plays were described as the most salient and influential activity that took place during the training. In the interviews, participants emphasized this training element with comments such as, “Hands down, the role play was the most influential piece of the teaching” (Participant #2), and “Role plays, I definitely feel like, was number one” (Participant #3).

Reluctance/Ambivalence

As important as role plays were to participants, it was also common for them to describe a certain level of initial reluctance to participate in role plays or ambivalence toward them, perceiving role plays as uncomfortable but valuable. As Participant #7 described, “So, as much as I dreaded the role plays, I liked that.” Likewise, Participant #2 reflected, “It’s funny because that’s the part I can’t stand the most, but it was actually the most helpful part.” Similarly, Participant #6 recalled “being very anxious in the beginning about the role plays – which ended up being the one thing I loved the most!”

Participants attributed their willingness to engage in role plays, despite their hesitations, to the supportive and strengths-based training environment. Participant #9 explained that her role play fears were assuaged when she realized, “This is a place to practice and learn. This is not a place to call you out and embarrass you.” Participant #5 described feeling more comfortable “after realizing that we were on the same boat and that everyone is focusing on our positives, and we’re not going to be pointing out, you know, the negatives.” Participant #8 also called attention to the important role of the “normalization and validation” in diminishing their initial discomfort with role plays.

Modeling by Trainers

One aspect of the role plays participants described as highly useful was how trainers used them to model PMTO skills. As Participant #5 pronounced, “Watching the leaders do the role play was obviously informative.” In this way, participants credited role plays as helpful for knowledge development. They expressed that seeing PMTO in action, demonstrated by experienced trainers—as opposed to just reading about the model or being told what to do—was very helpful. Participants noted how this gave them a sense of what a PMTO session would actually look like. They also liked, in the words of Participant #4, “that they showed us the ineffective way and the effective way because it is really interesting how those small, minor things make such a difference.”

Participating in Role Plays

The data indicated that another influential training element was when the participants themselves were invited to take part in role plays. During this training activity, participants would take turns portraying the role of the therapist and the caregiver as they enacted PMTO scenarios. Participants described that this valuable exercise allowed them to see other therapy styles, experience the perspective of the client, and practice their own skills. As Participant #8 explained, “It was important to see therapy done by other people in the group, but then also be the parent as well and go through those emotions.” Participant #5 added, “It puts you on the spot. And, you know, the more you practice that stuff the more you feel proficient.” Participating in role plays was another element of the training described as specifically useful for cultivating knowledge of the model. As Participant #1 stated simply, “I do think it was helpful to like learn the skill and be able to go practice it.”

Doing Role Plays with Families

Lastly, participants described being impacted by the awareness that they would be doing role plays with real families; this was a growth-producing element of the training, whether participants were working with a family at the time or were thinking of a hypothetical family. As Participant #10 explained, “I would apply [it] based off of how I already knew a family that I had been working with, or one that I wasn’t even doing PMTO with, just hypothetically, if I were to work with that family, what would this look like?” Participant #9 was able to get experience doing role plays with real families and described how it often produced a “light bulb” moment for parents in which they would disclose, “Oh, I didn’t realize that I was doing this!”

Engagement

The third theme identified in the data as influential to participants’ experience was the engaging nature of the training. Participants expressed how “I was excited to come every day” (Participant #9) and explained, “It was a long training, but it didn’t feel long…it felt easy to pay attention (Participant #2). In particular, the study data suggested certain features of the training that motivated participants to attend, participate, and learn.

Movement

One feature that participants expressed greatly appreciating was how movement was prioritized in the training. They referred to the “hands on” nature of the training and the “active learning” as particularly influential. For example, Participant #10 expressed, “The active learning piece was really huge.” Likewise, Participant #6 described the most meaningful piece of training as, “the getting up, the moving, the doing…. Not just PowerPoints all over the place and sitting there but being active in everything.” The training incorporated movement through role plays, small-group and large-group activities, and games. As Participant #8 reflected, “There was just so much activity. I didn’t think so much about movement until PMTO.”

Interactive

Another salient element of engagement evidenced in the data was the interactive nature of the training. As Participant #6 shared, “I love how interactive it is, how they pull you in.” Instead of passively listening to a lecture, participants felt “involved” in the training. This involvement included contact with trainers, other trainees, and coaches. Participant #2 explained that even though s/he had access to “tons of resources…that wasn’t as influential as it was with [the] real life, face-to-face interaction that I had.” In particular, participants valued how the trainers regularly sought out their input and perspective as part of the training process. Participant #10 expressed, “I just liked the fact that before we would just dive right into it, they would just ask about what were our take-aways.” Similarly, Participant #6 shared, “It was, you know, they were constantly asking us questions and moving us forward and checking in with us…and doing the debriefings. That was really important to me.”

Variety

Participants also described that being exposed to a variety of different training methods helped to promote engagement. Participant #9 remarked, “I think changing it up is helpful.” Participant #7 shared, “There was times that they were talking, there was times they were demonstrating, there was times that we were watching videos, and then we did role plays.” Participants also mentioned playing games, doing group activities, writing out comments, using their intervention manual, and having a guest speaker as examples of the various training activities. Importantly, participants noted that the different ways of presenting information made the training inclusive and accommodating to different learning styles. As Participant #6 stated, “I felt like the overall experience was for every type of learner. They had visual, audio, tactile. Like all the learning experiences were there.”

Structure

The fourth element described as helpful was the training structure. Participants expressed appreciation that the information was presented at an appropriate pace in a systematic, organized manner. Participant #7 described the training structure: “They would teach it and talk about it, and then they would demonstrate it, and then we would practice it. So, I think like that kind of structure helped us to learn.” Learning was also facilitated through home practice assignments, which participants said helped them to know what to expect and held them accountable.

Agenda

One element of the training structure emphasized by participants was the use of an agenda. Participants shared that having an agenda gave them a better understanding of what was included in each topic and “where your starting place is going to be, where your middle, and where your end is going to be” (Participant #10). Participants also realized that following an agenda in training was modeling what they should do when delivering PMTO. As Participant #7 reported, “It was sort of another example of how we should be doing PMTO, you know. So, we always have an agenda for the family. So, I think in that, in and of itself, was sort of a teaching tool.” In particular, participants expressed that having an agenda for the training facilitated their knowledge of PMTO.

Parking Lot

Another element of the training structure described as beneficial was the use of a “parking lot” – a process where participant questions that do not pertain directly to the topic at hand are written down in a conspicuous place and revisited at specific point later in time. Participant #5 appreciated how “that made it so that we had all of our questions or concerns answered.” Based on this experience during training, participants also believed this would be a powerful tool for structuring future PMTO sessions: “If things are being brought up that necessarily aren’t what we need to be addressed in PMTO, in that session, we can still put, you know, have a parking lot for them and then address it later so they still feel like their voice is being heard” (Participant #3).

Training Segments

A third structural element described as beneficial was how the training was delivered in segments and spaced out over time. This allowed the sizeable training content to be delivered in more manageable pieces. As Participant #2 explained, “The way they broke bigger concepts down into smaller, more absorbable pieces, it made it more palatable I would say. Because it was a lot.” In addition, this allowed participants to “actively go and use it in between the two sessions” (Participant #8). It appeared that the spacing between sessions allowed participants to practice the skills and then, “all of the questions that you had from your first training family and from your recordings, you can bring to the second meeting with you” (Participant #2).

Writing/Visuals

The fifth training element was the thorough incorporation of writing/visuals. Participants noted the useful way in which trainers wrote things down and used visual materials to augment the training. Participant #7 described, “It was good they used a lot of visual stuff… [like] the big paper and the markers.” Participant #9 added, “the notebook that they put on the wall so I could take notes,” referring to the way the trainers took notes on large adhesive-backed sheets of paper that were then posted around the room. Participant #1 shared, “I liked that they wrote a lot of things down and they didn’t just lecture.” Additional visual elements observed by the researchers during the training included displaying pre-written agendas and posters with key PMTO information as well as making use of the whiteboard and chat features on Zoom during online instruction. The use of visual materials was described as specifically helpful in supporting growth in PMTO knowledge. As Participant #4 explained, “I am a very visual learner so I was very appreciative especially when…they [would] use the big sticky papers and put it all over and I could take pictures. I could write the agendas down in my passport [i.e., notebook]. That helped.”

Working with Training Families

The sixth beneficial training element was working with training families. That is, as participants were learning PMTO, they were required to begin supervised use of the intervention with clients on their caseload, referred to as “training families.” As Participant #9 shared, “I think practicing with training families is, I am getting that chance to practice it, get it wrong, do it again.” She further explained, “It’s going to take some time to get it right. Actually, getting it wrong is how I learned. And knowing that and talking to the families about that too, like ‘this is training for me.’ That’s how I’m going to learn the most.” As Participant #6 acknowledged, part of the benefit of working with training families is the availability of a PMTO coach to answer questions and troubleshoot challenges that arise. She expressed, “Part of me feels like, ‘oh, those poor practice families, they are getting me when I don’t really know what I am doing.’ But another part of me is glad that we get to have two practice families with a coach right there with us…I think it is good for teaching and education.” Participants also described accounts of how working with training families allowed them to witness the effectiveness of the intervention firsthand. As Participant #2 shared, “I had a training family that came in…and she was excited about it, and it still seems to be working. She still seems excited and still participating, cooperating. It was just, that kind of pushed me along.”

Experiencing the PMTO Model

Participants acknowledged the ways in which the training process was modeled after the intervention itself, so that trainees were able to experience the PMTO model themselves. This was identified as the seventh and final beneficial training element. In the words of Participant #6, “the whole training was a PMTO session.” The research team noted that aspects of the PMTO intervention modeled in the training included, for example, providing support, focusing on strengths, teaching through role play, emphasizing movement, using an agenda and “parking lot” to structure sessions, and providing visuals – the same features identified by participants as beneficial in their training experience. Participant #7 recognized, “They basically just used PMTO on us for the eight days, you know? Which was really- it showed you how just that whole approach is so effective because you kind of experienced a little piece of it.” Similarly, Participant #8 noted how experiencing PMTO during training offered a greater understanding of the model: “I appreciated that they modeled throughout the entire training the exact thing that were supposed to be doing. I felt silly, but I wanted to earn scoobies too. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is why they do it!’”

Discussion

This study used a qualitative approach to identify elements of the GenPMTO training process perceived as beneficial, utilizing data from clinicians who were learning this evidence-based model. The findings demonstrated, overall, that clinicians in this study sample expressed a high level of satisfaction with the training and believed they had experienced growth in their attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in PMTO. Further, this study identified seven specific training elements that participants described as fostering a positive learning environment: support, role plays, engagement, structure, writing/visuals, working with training families, and experiencing the PMTO model. Although each of these elements has unique and distinctive characteristics, they were noted to occur in the training in an integrated and mutually reinforcing manner.

Efforts to systematically advance real-world training in EBPs are an important element of the implementation science agenda (Davies et al. 2010; NIH 2019). For example, concurrent work has used data from experts in EBP implementation/therapist training to identify methods for supporting the development of core therapist skills across different family-based EBPs (Miller 2021). Similar to our study, Miller found support for the importance of a variety of active learning strategies (e.g., role play), supervision/coaching, and peer support. This suggests there may be beneficial training practices in common across different EBP models. Our study also identified additional training elements, including the dynamic use of writing/visuals and having trainees experience the PMTO model, which can help to expand understanding of beneficial training practices. To unite knowledge on EBP training, implementation science scholars have called for researchers to use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to organize their findings (Beidas et al. 2011).

In response, we will use the CFIR framework to discuss how our study findings relate to the broader literature on EBP training and intervention implementation. The overall goal of the CFIR is to provide a comprehensive inventory of the various factors that may influence implementation of an EBP (Damschroder et al. 2009). The CFIR synthesizes constructs from multiple theories and models of dissemination and implementation into five broad domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, individual characteristics, and implementation process (Damschroder et al. 2009). These domains are thought to interact with one another and mutually influence implementation. The CFIR framework can be used to contextualize our study findings within the broader implementation science literature.

One salient study finding was the importance of a supportive training context. When clinicians perceived their training environment to be strengths-based and encouraging, this fostered a safe learning experience where they could develop knowledge and confidence in the GenPMTO intervention. This finding is in line with research indicating that supportive leadership is an important dimension of EBP implementation (Aarons et al. 2014). The GenPMTO training philosophy focuses on parallel process, so that trainers implement the same positive relational practices with their trainees as the trainees will eventually teach to parents (e.g., teaching through encouragement, positive involvement; Forgatch and Patterson 2010). This manifests through various strengths-based teaching processes (Forgatch and Domenech Rodríguez 2016), such as encouragement/support (e.g., focusing on the positives, use of verbal praise and tangible reinforcers), proactively preventing/managing resistance, and taking responsibility if a failure occurs (e.g., by conceding a lack of proper preparation on the part of the trainer). Study participants identified the importance of the support they received from the GenPMTO coaches and the benefits of receiving this support in an ongoing manner over time. Research on EPBs in general (e.g., Edmunds et al. 2013) and on GenPMTO specifically (Akin 2016; Akin et al. 2014) has highlighted the supportive functions of strengths-oriented coaching and how continued access to consultation with coaches is a valuable source of ongoing support. In fact, research suggests that clinicians show more favorable attitudes toward models that require ongoing consultation (Barnett et al. 2017). Moreover, our findings extend knowledge of the role of support during EBP training by indicating that support received initially during the training process from the model trainers as well as from fellow trainees may also be important for setting the stage for a positive experience. In addition, participants in this study identified how receiving access to resources and tangible materials were important sources of support.

Within the CFIR framework (Damschroder et al. 2009), the theme of support can be understood as an important element of the inner setting that may help to explain the successful, sustained implementation of the GenPMTO model in Michigan. More specifically, the Michigan PMTO implementation climate, and particularly the learning climate, is characterized by a sense of encouragement, safety, and responsiveness. In addition, our findings suggest how successful implementation sites demonstrate a readiness for implementation by offering available resources and access to information and knowledge that support clinicians during the EBP training.

Another training element highlighted in our study findings was the importance of role plays. Data from clinicians participating in the GenPMTO training aligned with reports in the broader literature on training practices to underscore the value of active learning through role plays (e.g., Cross et al. 2007; Joyner and Young 2006; Matthews et al. 2014). The value of role plays is a message worth repeating, as our findings indicate that training attendees may initially feel nervous or express reluctance at the notion of participating in role plays. However, instead of forgoing the use of role plays because of trainee ambivalence, our findings suggest that trainers may be able to successfully incorporate role plays in training by first modeling the role plays to trainees and then inviting them to participate in the role plays within the context of a safe and supportive environment. Role plays are an integral part of the GenPMTO model and training process (e.g., Forgatch et al. 2004; Forgatch and DeGarmo 2011; Forgatch and Domenech Rodríguez 2016) and have been identified by caregivers as an important contributor to change in their parenting practices during participation in GenPMTO (Holtrop et al. 2014). The current findings extend this work by implicating role play as an important contributor to clinicians’ experiences of learning the PMTO model. Furthermore, the study findings suggest that modeling by the trainers, practice during training, and application with families are all important facets of role play.

An interesting application of the CFIR framework (Damschroder et al. 2009) with regard to the function of role plays has to do with the concept of trialability. Trialability is considered an intervention characteristic that involves being able to test or try out a model prior to full implementation (Damschroder et al. 2009). In our study, participants identified that being able to practice PMTO through role plays, experience the perspective of the client, and use role plays with families during the course of the training were all valuable training activities. It is notable that all of these activities allowed participants the opportunity to experiment with the model on a trial basis. In a similar manner, this characteristic of trialability may also explain why working with training families was identified as another beneficial training element. In this way, the CFIR model may be helping us pinpoint an important training process operating within GenPMTO: the opportunity for participants to test out the model and confirm its benefits.

In addition, our study documented how working within a clear structure was an element of the training that participants found beneficial. GenPMTO trainings are conducted in an organized and systematic manner that mimics the structure of the intervention itself. For example, participants appreciated following an agenda for each day of the training and receiving or developing agendas for how each PMTO topic might be presented to families. Some scholars have noted how the seemingly rigid nature of manualized interventions can deter clinicians from engaging with evidence-based approaches (e.g., Cook et al. 2017; Dattilio et al. 2014). Our findings suggest that an appropriate degree of structure may be welcomed by clinicians and offer tentative support to the growing literature showing that interventions with a structured format are seen as helpful and valuable by providers (Aarons and Palinkas 2007; Barnett et al. 2017). Introducing and illustrating the intervention structure during training may be a beneficial element for influencing positive attitudes, knowledge, and feelings of confidence in the model.

According to the CFIR model (Damschroder et al. 2009), the knowledge and beliefs of a clinician toward an EBP is one of the characteristics of individuals that influences implementation. In our study, the majority of participants reported that the structure that accompanies GenPMTO implementation– particularly generating and using agendas during the training – helped to positively influence their knowledge of the GenPMTO model. This suggests that EBP training practices, such as the use of structured agendas, may be able to positively influence the characteristics of individuals that support successful intervention implementation.

Implications for Practice: Enhancing Training in Evidence-Based Practices

Foster a Supportive Environment

Our findings suggest that fostering a supportive environment for trainees may be a beneficial way to set the stage for a positive training experience. For example, trainers could use a strengths-based approach for instruction, work to intentionally create a sense of camaraderie within the training group, and/or ensure the training is responsive to the questions and concerns of participants. Connecting trainees with coaches who can provide supervision during the training process may also help to provide an important element of support. Otherwise, research has shown practitioners who struggle to access consultation or supervision are less likely to use a new intervention (Sanders et al. 2009). Moreover, it may be important for this support to extend beyond just the initial training experience. Mental health professionals have reported that concerns about accessing ongoing support and supervised opportunities to practice new skills pose a barrier to adopting new interventions (Cook et al. 2009). On the other hand, receiving ongoing coaching can support practitioners through strengths-oriented feedback, skill-building, problem-solving and adapting treatment to real-world situations, and aiding intervention fidelity (Akin 2016).

Provide Opportunities to Experience Success

EBP training may also be enhanced by providing trainees with opportunities to experience success with the new intervention. For example, role plays can allow participants to go beyond learning about the model to actively applying the new skills in the safety of the training context. This aligns with recommendations to offer deliberate practice with feedback to help clinicians develop expertise in EBPs (Beidas et al. 2011). Effective use of role play may include modeling by the trainers, guided participation of trainees, troubleshooting, and debriefing (e.g., see Forgatch and Domenech Rodríguez 2016). To set participants up for success, trainers may consider structuring the learning process by breaking up the training into manageable segments, using agendas to communicate key session elements, and providing visual cues for trainees. Additionally, practitioners have reported that their preference for EBPs is influenced by past positive experiences with the model (Nelson et al. 2006). Therefore, having participants work with families as part of the training process may also offer important opportunities for success. In fact, research has demonstrated that receiving positive feedback from families and seeing observable improvements when using a new intervention significantly predict higher use of the new intervention (Sanders et al. 2009).

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The findings of this study must be considered in light of its limitations. First, study data were derived from a small sample of participants attending a single GenPMTO training in a Midwestern state, and so appropriate caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings. The experiences of participants in this study cannot be understood to represent the experiences of all EBP training participants. For example, participants in this sample had relatively few years of experience working in the mental health field ( ≤5 years). Future research should continue to investigate beneficial training elements among other groups of mental health professionals and from different EBP trainings. Second, the present qualitative study sought to learn which training elements were perceived as beneficial by clinicians. Our study did not assess knowledge gained or test whether the reported training elements were associated with improved clinical practice, although these areas would be informative next steps for future research. Further, research team members attended the focal training alongside the eventual study participants. While we believe attending the training served as a form of “prolonged engagement” (Lincoln and Guba 1985) that allowed the researchers to earn the trust of study participants and gain a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of interest as appropriate for a qualitative study, it is possible this may have impacted the data generated from the participant interviews. For example, this may have led to bias associated with demand characteristics, where participants might have been influenced to provide responses they perceived to be in line with the aims of our study and/or what they believed the researchers wanted to hear. This remains a salient limitation of this study. In addition, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the second week of training took place though a virtual platform. While this was atypical at the time, PMTO training in Michigan has continued in a virtual format throughout the pandemic, with plans to maintain a hybrid training format into the future. The focal training investigated in this study was therefore very appropriate for informing subsequent real-world practice. Future empirical work could expand on this study by investigating if beneficial training elements differ by training modality.

In conclusion, enhancing the process through which clinicians are trained in EBPs is an actionable strategy that may help to expand the implementation of effective mental health interventions. In the words of one study participant, “The method of teaching is just as important as what you’re teaching. You know, like the method is just as important as what the content is.” In this way, the current study makes an important contribution to the literature by identifying potentially beneficial training elements of GenPMTO. With continued research, including efforts to build on these qualitative findings by integrating quantitative analyses of related research questions, we can make progress toward identifying effective elements of EBP training.

Notes

The Michigan implementation site refers to their individual family model of GenerationPMTO as PMTO. Accordingly, we will use the term PMTO in this manuscript to refer to this Michigan model of GenerationPMTO.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence- based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MHSR.000002451.12294.65.

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). The implementation leadership scale (ILS): development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 9(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-45.

Aarons, G. A., & Palinkas, L. A. (2007). Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3.

Akin, B. A. (2016). Practitioner views on the core functions of coaching in the implementation of an evidence-based intervention in child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review, 68, 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.010.

Akin, B. A., Mariscal, S. E., Bass, L., McArthur, V. B., Bhattarai, J., & Bruns, K. (2014). Implementation of an evidence-based intervention to reduce long-term foster care: Practitioner perceptions of key challenges and supports. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.006.

Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 322(7294), 1115–1117. 10.1136%2Fbmj.322.7294.1115.

Barnett, M., Brookman-Frazee, L., Regan, J., Saifan, D., Stadnick, N., & Lau, A. (2017). How intervention and implementation characteristics relate to community therapists’ attitudes toward evidence-based practices: A mixed methods study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(6), 824–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0795-0.

Barry, C. A., Britten, N., Barber, N., Bradley, C., & Stevenson, F. (1999). Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 9(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121677.

Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence‐based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems‐contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x.

Beidas, R. S., Koerner, K., Weingardt, K. R., & Kendall, P. C. (2011). Training research: Practical recommendations for maximum impact. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(4), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0338-z.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Chamberlain, P., Brown, C. H. & & Saldana, L. (2011). Observational measure of implementation progress in community based settings: The Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC).Implementation Science, 6, 16.

Clark, R. C. (2019). Evidence-based training methods: A guide for training professionals. American Society for Training and Development.

Connor-Smith, J. K., & Weisz, J. R. (2003). Applying treatment outcome research in clinical practice: Techniques for adapting interventions to the real world. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-3588.00038.

Cook, J. M., Biyanova, T., & Coyne, J. C. (2009). Barriers to adoption of new treatments: an internet study of practicing community psychotherapists. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(2), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0198-3.

Cook, S. C., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2017). Evidence-based psychotherapy: Advantages and challenges. Neurotherapeutics, 14(3), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd Ed.). Sage.

Cross, W., Matthieu, M., Cerel, J., & Knox, K. (2007). Proximate outcomes of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in the workplace. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 659–670. https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.659.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Dattilio, F. M., Piercy, F. P., & Davis, S. D. (2014). The divide between “evidenced‐based” approaches and practitioners of traditional theories of family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12032.

Davies, P., Walker, A., & Grimshaw, J. (2010). A systemic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implementation Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-14.

Dishion, T., Forgatch, M., Chamberlain, P., & Pelham, III, W. E. (2016). The Oregon model of behavior family therapy: From intervention design to promoting large-scale system change. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 812–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.002.

Edmunds, J. M., Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices: Training and consultation as implementation strategies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(2), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12031.

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782.

El-Tannir, A. (2002). The corporate university model for continuous learning, training, and development. Education & Training, 44, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910210419973.

Forgatch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2011). Sustaining fidelity following the nationwide PMTO™ implementation in Norway. Prevention Science, 12, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0225-6.

Forgatch, M. S., & Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. (2016). Interrupting coercion: The iterative loops among theory, science, and practice. In T. J. Dishion & J. J. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics (pp. 194–214). Oxford University Press.

Forgatch, M. S., & Gewirtz, A. H. (2017). The evolution of the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training: An intervention for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In J. R. Weisz & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (3rd ed; pp. 85–102). New York: Guilford.

Forgatch, M. S., Bullock, B. M., Patterson, G. R., & Steiner, H. (2004). From theory to practice: Increasing effective parenting through role-play. Handbook of mental health interventions in children and adolescents: An integrated developmental approach, 782–813.

Forgatch, M. S., & Patterson, G. R. (2010). Parent Management Training—Oregon Model: An intervention for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In J. R. Weisz & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents (pp. 159–177). The Guilford Press.

Forgatch, M. S., Patterson, G. R., & Gewirtz, A. H. (2013). Looking forward: The promise of widespread implementation of parent training programs. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 682–694. 10.1177%2F1745691613503478.

Forman, J., & Damschroder, L. (2007). Qualitative content analysis. In Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Fossum, S., Kjøbli, J., Drugli, M. B., Handegård, B. H., Mørch, W.-T., & Ogden, T. (2014). Comparing two evidence-based parent training interventions for aggressive children. Journal of Childrens Services, 9(4), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcs-04-2014-0021.

Gallo, K. P., & Barlow, D. H. (2012). Factors involved in clinician adoption and nonadoption of evidence- based interventions in evidence-based interventions in mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 19(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2012.01276.x.

Ghandour, R. M., Sherman, L. J., Vladutiu, C. J., Ali, M. M., Lynch, S. E., Bitsko, R. H., & Blumberg, S. J. (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18, 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

Hamilton, A. B., & Finley, E. P. (2019). Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Research, 280, 112516.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112516.

Herschell, A. D., Kolko, D. J., Baumann, B. L., & Davis, A. C. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 466.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005.

Hoagwood, K., & Olin, S. S. (2002). The NIMH blueprint for change report: Research priorities in child and adolescent mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(7), 760–767. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200207000-00006.

Holtrop, K., Parra-Cardona, J. R., & Forgatch, M. S. (2014). Examining the process of change in an evidence-based parent training intervention: A qualitative study grounded in the experiences of participants. Prevention Science, 15(5), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0401-y.

Joyner, B., & Young, L. (2006). Teaching medical students using role play: Twelve tips for successful role plays. Medical Teacher, 28(3), 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600711252.

Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behaviour research and therapy, 88, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.004.

Knutson, N. M., Forgatch, M. S., Rains, L. A., Sigmarsdóttir, M., & Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. (2019). Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP): The manual for GenerationPMTO (3d ed.). [Unpublished training manual]. Implementation Sciences International, Inc. Eugene, OR.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Matthews, M., Gay, G., & Doherty, G. (2014, April). Taking part: role-play in the design of therapeutic systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 643–652).

Miller, D. L. (2021). Core Therapist Skills Supporting Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices with Serious Emotionally Disturbed Children in Community Mental Health Settings: A Modified Mixed Methods Delphi Study (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University).

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of counseling psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250.

National Institutes of Health. (2019). Dissemination and implementation research in health (R01 Clinical trial optional). (PAR-19-274). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-19-274.html.

Nelson, T. D., & Steele, R. G. (2007). Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: Practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x.