Abstract

The influence of academic support on students’ academic and personal development has been previously demonstrated. The objective of this study was to present a validation of the Perceived Academic Support Questionnaire (PASQ). This scale has three dimensions: academic support from (1) teachers, (2) family, and (3) peers. For the reliability analysis, we estimated the Cronbach alpha and Composite Reliability Indices (CRIs). Factorial validity was assessed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and external validity was tested via a structural equation model in which the dimensions of academic support predicted academic motivation. The CFA fit indices showed very good fit to the data, supporting the theoretically proposed three-factor structure. The reliability indices, considering Cronbach alpha and CRI, were adequate for all dimensions and the predictive model fit was satisfactory. Teacher and parental academic support had a positive impact on academic motivation. On the contrary, a negative relationship between peer support and academic motivation was found. The evidence provided supports for the use of the PASQ as a brief academic support scale in future research.

Highlights

-

The development of rigorous instruments for measuring academic support is needed.

-

The Perceived Academic Support Questionnaire (PASQ) has shown adequate psychometric properties in a sample from the Dominican Republic.

-

Significant positive correlations have been found among parental and teacher’s academic support and academic motivation.

-

Significant negative relation was found among peers’ support and academic motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

The academic support can be understood as the emotional and instrumental support given by significant others to the student in the academic context (Alfaro et al., 2006; Chen, 2005). Generally, when we speak about academic support we refer to the academic support perceived by students, regardless of its possible incongruence with the perception by teachers, parents or peers (Choe, 2020). The influence that support from the teachers, families, or peers has on adolescents’ academic lives has been the object of study in many recent research studies (Gutiérrez et al., 2017), with several of these showing their roles as protective factors against the development of anxiety or depression (Arora et al., 2017; Boudreault-Bouchard et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2010; Smokowski et al., 2015, Rueger et al., 2016). Specifically, Lei et al. (2018) carried out a meta-analysis in order to explore the relationship between teacher support and students’ emotions. After evaluating 65 studies they concluded that students with more support from teachers showed more positive emotions.

In addition to the importance of support (from various sources) to the personal development of adolescents, there is also evidence for its relevance in academic domains. Specifically, evidence has been uncovered that suggests a relationship between academic support from parents, teachers and/or peers and academic achievement (Jelas et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2012; Wentzel et al., 2016; Wang & Eccles, 2012), academic motivation (Alfaro et al., 2006; Alfaro & Umaña-Taylor, 2015; Horanicova et al., 2020; Plunkett & Bámaca-Gómez, 2003; Sands & Plunkett, 2005), and school engagement or involvement (Clark et al., 2020; Estell & Perdue, 2013; Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Mikami et al., 2017; Ramos-Díaz et al., 2016, Virtanen et al., 2014). When teachers were respectful and took care of their students, these young people seemed to be more committed to studying the subject in question and were more polite to the rest of the class (Chiu & Chow, 2011; Longobardi et al., 2016). Furthermore, there is also evidence for the opposite effect: when teachers are disrespectful, students were less cooperative (Miller et al., 2000).

Based on traditional educational theories as the attribution theory, expectancy-value theory, goal theory, self-determination theory, self-efficacy or self-worth motivation theory, positive interpersonal relationships could affect academic motivation by directly impact its base: students’ beliefs and emotions (for an extensive review see Martin and Dowson, 2009). Through these relationships, students internalize the beliefs valued by others and increase their sense of belonging, which translates into greater motivation and self-esteem. Recent studies have empirically deepened the study of the effect of academic support and academic motivation. Horanicova et al. (2020) evidenced that the support from teachers and peers improves student’s satisfaction with schools and their education’s relevance perception. These results would be consistent across genders (Horanicova et al., 2020). The importance of academic support would be especially relevant on students with low family socioeconomic status, where the academic support acts as a buffer of its negative impact on academic engagement and attitudes towards education (Horanicova et al., 2022). Although previous literature has shown the relevance of support from home and school, peer support seems to be less important than other sources of support (Saleh et al., 2019, Sethi & Scales, 2020). This relationship with motivation is especially relevant given that through it, academic support has an indirect impact on academic performance (Sethi & Scales, 2020).

Bronfenbrenner’s (1989) ecological model is frequently used in the literature to help understand the influence of contextual variables such as support from teachers, families, or the student peer group in adolescents’ development. This model highlights the importance of understanding the development of people as a process of constant interaction between individuals and their environments. Specifically, Bronfenbrener (1989) emphasised the importance of ‘significant others’, understood as individuals in the person’s immediate environment who directly influence them. Regarding adolescents, these significant others usually correspond to their teachers, parents, and peers (Alfaro, et al., 2006) as socialisation agents; the resources they provide to students to facilitate their academic achievement can be defined as ‘academic support’ (Alfaro et al., 2006). This academic support may be bestowed in different ways such as emotional support (understanding a student’s feelings and encouraging them) or instrumental support (helping them with homework and to understand the topics they are studying) (Chen, 2005). These factors, emotional and instrumental support, are included in the framework proposed specifically for the teacher-student interactions by Hamre and Pianta (2007), and tested by Hamre et al. (2013), which also includes classroom organization as a relevant factor in the students learning promotion.

There are several different approaches to academic support and these have resulted in different scales and studies that, despite measuring the same thing, do so with differentiating nuances (Malecki & Elliott, 1999). Additionally, most research has focused on measuring the influence of the support from one of these groups (Cattley, 2004), rather than taking a multidimensional approach to the concept, jointly considering different socialisation agents as sources of academic support. Specifically, a large volume of research has explored the relationship between family and parental support and the academic development of students, but less attention has focussed on their peers (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). However, there is broad consensus that social support has a multidimensional nature, and that its various dimensions probably relate in different ways to particular types of outcomes (Sarason & Sarason 2009). Thus, continued investigation to expand our understanding of this area and to improve the measurement instruments available will enable rigorous research in the field of educational psychology to understand the effect of academic support when teacher, parental and peer support are considered.

Our literature review highlighted the availability of several interesting instruments for studying academic support. For example, the Student Social Support Scale (SSSS; Nolten, 1994; Malecki & Elliott, 1999), based on Tardy’s (1985) social support model, measures emotional, informational, instrumental, and appraisal support from teachers, parents, peers, and close friends. This scale contains a total of 60 items and its language is aimed at primary school students rather than adolescents. To overcome these limitations, Malecki et al. (1999) developed the Scale of Social Support for Children and Adolescents (CASSS). Despite having similarities with the SSSS, the CSASSS is comprised of 40 items and includes a version for children and adolescents. With satisfactory results from their validation (Malecki & Demaray, 2002) studies, both these scales and adapted versions of them continue to be widely used (Ciarrochi et al., 2017; Maiuolo et al.; 2019; Archer et al., 2019), but they are also both considered to be too long for administration alongside other instruments. Additionally, they measure social support in the academic field rather than academic support as defined above, even though both these factors are closely related.

Thompson and Mazer (2009) and Mazer and Thompson (2011) subsequently proposed an instrument focused on academic support, the Student Academic Support Scale (SASS). This scale was designed with university students in mind and exclusively measures peer support. These authors developed another questionnaire for parental academic support which was oriented towards individuals not yet at an undergraduate level, the Parental Academic Support Scale (PASS; Thompson & Mazer, 2012; Mazer & Thompson, 2016). The PASS understands parental academic support as the frequency of communication between parents and teachers about academic performance, classroom behaviour, preparation, hostile interactions, and student health. However, once again, these scales are specific of peers or parent support rather than multidimensional, and in the latter case, does not focus on the support perceived by students.

Another contribution of special relevance in this arena is the scale developed by Sands and Plunkett (2005) to measure the academic support derived from the mothers, fathers, teachers, and friends of Latino adolescents in the United States. As one of its differentiating characteristics, the Significant Other Academic Support Scale registers students’ perceptions of their mothers and fathers separately. Gutiérrez et al. (2017) generated a dimension termed ‘family support’ by combining the scores obtained from the separate father and mother support factors on this scale. In their research, these authors then measured family support using this dimension, as well as teacher and peer support by adapting two subscales from Lam et al. (2012).

In summary, although academic support has been evidenced as a relevant construct in the academic and personal development of students, a brief and integrated instrument that considers different sources of support (teacher, family and peers) is still required to measure it. Following the adaptations suggested by Gutiérrez et al. (2017), here we propose a scale of perceived academic support, the Perceived Academic Support Questionnaire (PASQ): that includes the dimensions of family support (based on Sands and Plunkett (2005)), teacher support, and peer support (based on Lam et al., 2012).

Purpose of this study

This study aims to validate a support instrument based on the aforementioned scales in a sample of high school students in Dominican Republic. In the context of the Dominican Republic, and in spite of having implemented advances in educational improvement and investment (Acción Empresarial para la Educación, EDUCA, 2015; Iniciativa Dominicana por una Educación de Calidad, IDEC, 2014), the country continues to show low academic achievement rates (Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico, OECD, 2016). Having an easy-to-use tool to detect the levels of social support (from parents, teachers and peers) would be a step forward in the detection of possible obstacles to the improvement of academic performance.

Therefore, the specific aims of the study includes: (1) to test the three-factor structure validity of the PASQ in Dominican Republic students; (2) to test the reliability of the PASQ; and (3) to test the external validity by proving its predictive power on academic motivation, doing so we expect to find empirical support for the theoretically expected relationships in order to obtain evidences for the interpretation of the results.

Method

Participant

Our sample comprised 1,712 secondary students from educational districts 04–03 and 11–01 of the Dominican Republic. All the regions of Dominican Republic were contacted and finally the study was carried out where the authorities showed interest and availability to participate. Within the available regions, districts were chosen for the presence of significant challenges in terms of their indicators of academic success. The inclusion criteria for participants were: a) being a student from an educational center in districts 04-03 or 11-01; b) being a high school student; and c) consenting to participate. The aforementioned districts showed a population of 3387 students, considering a level of confidence of 99% and 3% margin of error (with p = q = 0.5), 1712 students were sampled. The lack of response from them was negligible (less than 1%).

Of the total sample, 902 were female (52.69%) and 809 were male (47.25%), one student did not declare gender. All the participants were aged between 12 and 20 years (mean = 14.73 ± 1.2 years). A total of 1,278 students belonged to public institutions (74.65%), while 268 went to private institutions (15.65%) and 166 to semi-official educational institutions (9.70%). Of all the students, 404 were from rural areas (23.6%) and 1,308 from urban areas (76.4%). The most common family types were nuclear (52.37%) and single-parent families (32.63%), followed by extended families (9.20%) and other situations (5.80%).

Procedure

The survey procedure meets the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (APA) and it received the ethics approval of the Ministry of Education of the Dominican Republic and the directors of the education institutions. The researchers contacted with the educational authorities to communicate the goals and procedure of the study. The schools informed teachers, families and students about the aim of the study. The schools were randomly selected among all the available ones and then invited to voluntarily participate. They did not get any reward for their participation.

The survey team was formed by three district educational technicians and two school psychologists who were in charge of distributing, supervising the implementation, and collecting the questionnaires completed in the schools. The questionnaires were administered at the schools during the first teaching hour. The students needed around 45 minutes to fulfil the self-administered questionnaire. All but 3 students completed the survey properly, whose responses were removed and replaced with the responses of 3 new students.

Instruments

We measured academic support from teachers, families, and peers using the PASQ (Cuestionario de Apoyo Académico Percibido, referred to as the CAAP in Spanish) which was originally developed in Spanish and was adapted as suggested by Gutiérrez et al. (2017). The resulting PASQ scale has a total of 12 items belonging to 3 dimensions: family, teacher, and peer support. The response scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Item contents are presented in the Table 1. The Spanish version of the scale is available under request.

The family support dimension is based on the parental support dimensions from the Significant Other Academic Support Scale by Sands and Plunkett (2005), while the teacher and peer support dimensions were adapted from two of the subscales published by Lam et al. (2012), which had itself adapted items from the Caring Adult Relationships in School Scale and Caring Peer Relationships in School Scale, both from the California Healthy Kids Survey (WestEd, 2000). Gutierrez et al. (2017) reported good psychometric properties for the family support dimension in an Angolan sample: its reliability was α = 0.73 and the one-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) satisfactorily fitted the data (χ2(9) = 34.56, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.037). Additionally, they tested the psychometric properties of the parents and peer support scale with good results: its reliability was 0.71 and 0.70 and the two-factor structure satisfactorily fitted the data (χ2(8) = 32.74, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.039).

Academic motivation was measured using the Adolescent Academic Motivation Scale used in Plunkett and Bámaca-Gómez (2003). This questionnaire contains a total of 5 Likert-type items that evaluate a single dimension (e. g. “In general, I like school”). The response scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this sample, its reliability was α = 0.71 and the one-factor CFA produced a satisfactory fit: χ2(5) = 57.388 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.975, RMSEA = 0.078, 90% CI [0.061, 0.095], SRMR = 0.024.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics and reliability for the instrument were calculated using SPSS software (version 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY.). The descriptive statistics included the item means, standard deviations, inter-item correlations, and homogeneity; for the reliability analysis we estimated the Cronbach alpha for all the dimensions included in the scale. This reliability index is considered acceptable when it scores above 0.70, with values exceeding 0.80 being preferable (Cicchetti, 1994; Clark & Watson, 1995). Although Cronbach’s alpha is the most widely used reliability index, it has been criticised because, among other reasons, it can underestimate the true reliability (Raykov, 2004). The composite reliability index (CRI) has been shown to better estimate reliability than the Cronbach alpha (Raykov et al., 2010) and so, we decided to calculate and consider both these reliability indices.

Factorial validity was assessed via CFA. To check the model fit, we used the chi-square test, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. The model fit was considered acceptable if the CFI exceeded 0.90 (with 0.95 being preferable), and RMSEA and SRMR values were below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). These analyses were carried out with Mplus software (version 8.4, Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) using WLSMV (Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance corrected) considering the ordinal nature of the data and the non-multivariate normality. External validity was tested relating academic support and academic motivation given that these variables have been consistently associated in previous research (Jelas et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2012; Wentzel et al., 2016; Wang & Eccles, 2012). We constructed a structural equation model in which the three dimensions of academic support that predicted academic motivation were tested, using the same CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR values to evaluate the overall model fit. In addition, we also examined the relationships between these variables.

Results

Factorial validity

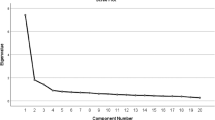

Although previous literature recommends a three-factor model, a one-factor structure CFA was tested as a baseline model. The one-factor structure does not show a good fit to the data: χ2(54) = 2832.779 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.794, RMSEA = 0.173, 90% CI [0.168, 0.179], and SRMR = 0.105. Consequently, a three-factor structure CFA was tested and fit as good: χ2(51) = 212.566 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.988, RMSEA = 0.043, 90% CI [0.037, 0.049], and SRMR = 0.023 which indicated that the theoretical a priori factor structure adequately fit the data.

Figure 1 shows the tree-factor model, and the standardised loading estimates. Every indicator had a high and significant loading (p < 0.001) in its hypothesised factor. The standardised loadings ranged from a minimum of 0.690 to a maximum of 0.822. As hypothesised, the three factors were positively correlated, but the correlations were not sufficiently high to jeopardise their discriminant validity. Notwithstanding, the highest correlation was found between teacher and peer support.

Internal consistency and inter-item correlations

Table 1 includes means, standard deviations, homogeneity (corrected item overall correlation), skewness and kurtosis statistics of the items. The descriptive statistics and correlation among dimensions has been included in Table 2. Table 2 also includes the information for academic motivation. The Cronbach alpha was 0.69 for the teacher support dimension, 0.73 for peer support, and 0.87 for parental support. If we removed any of the items, the Cronbach alpha for the dimension decreased. In addition, these results were supplemented with the estimation of CRIs at 0.76 for teacher support, 0.79 for peer support, and 0.90 for parental support. Thus, in this sample, these results showed adequate reliability for all the dimensions.

External validity

To assess external validity, we tested a structural equation model with latent factors in which the latent factor of academic motivation was predicted by the three dimensions of academic support. The goodness of fit indices for these analyses were satisfactory: χ2(113) = 497.098 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.045, 90% CI [0.041, 0.049], and SRMR = 0.029. The analytical results of this model (Fig. 2) showed that the three dimensions of academic support predicted 59.1% of the variance in academic motivation (R2 = 0.591); all these relationships were statistically significant. Parental and teacher academic support positively predicted academic motivation, with structural coefficients of β = 0.607 (p < 0.001) and β = 0.369 (p < 0.001), respectively. However, peer support was negatively related to academic motivation (β = −0.145, p = 0.002).

Discussion

It has often been pointed out in the scientific literature that the academic support that students receive is an important factor in their academic and personal development. The academic support given by teachers, families, and peers positively affects student success, motivation, engagement, and well-being (Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Jelas et al., 2016; Sands & Plunkett, 2005; Tomás et al., 2020), while its absence has been related to lower educational expectations and higher levels of school truancy (Al-Alwan, 2014; Boudreau et al., 2004; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2012; Yang, 2004). Consequently, considering the importance of these factors in education, brief instruments to measure them, that integrate the dimensions of teacher, family, and peer support, are required to continue rigorous research in educational psychology. The support of various socialization agents should be taken into account in order to be able to disentangle the specific role of each one and check if any of them is more relevant than the rest in the promotion of specific educational variables. Thus, the Perceived Academic Support Questionnaire (PASQ) (in its original Spanish version, the Cuestionario de Apoyo Académico Percibido or CAAP) was developed to address this need. The PASQ incorporates the contributions of previous studies and has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in a sample of students from the Dominican Republic.

Regarding factor validity, the CFA carried out for the a priori three-factor structure showed particularly good overall fit indices and there was evidence that the data reproduced the proposed theoretical model. Results showed positive and statistically significant correlations between the three factors or sources of academic support. Indeed, contextual variables such as support from teachers, families, or the student peer group are not independent elements, but are highly interrelated. Therefore, an instrument such as the PASQ allows to cover the three most important sources of support in adolescents’ development at a time, while also considering their interdependency.

Regarding reliability estimates, two indices were used to analyse the internal consistency of the PASQ. Firstly, Cronbach alphas produced adequate results for all the dimensions except for teacher support which fell below the cut-off criteria of 0.7 although it was remarkably close to it with a score of 0.69. Although the Cronbach alpha index has several limitations—such as assuming tau-equivalence or being a lower bound for the true reliability (Raykov, 2004)—it is still the most widely used tool for this purpose. To compensate for these flaws, we calculated the CRI for each dimension, which also exceeded the cut-off criteria and produced adequate results in all the dimensions. Reliability results were slightly better than the results obtained by Gutiérrez et al. (2017) with a sample of Angolan students.

As proof of the predictive validity of the PASQ, its relationship with academic motivation was analysed via a structural equation model in which the three dimensions of academic support predicted the latent factor of academic motivation. Significant positive correlations were obtained between parental and teacher academic support and academic motivation. These results concur with those previously reported in the literature (Alfaro et al., 2006; Isik et al., 2018; Horanicova et al., 2020; Plunkett & Bámaca-Gómez, 2003; Sands & Plunkett, 2005; Song et al. 2015), with a significant negative relationship being identified between peer support and academic motivation. However, the relationship between these latter two variables remains somewhat controversial. While many studies have found a positive relationship between peer support, engagement, and positive attitudes towards studying, it was less clear in other works (Li et al., 2010; Saleh et al., 2019; Sethi & Scales, 2020; Veentra et al., 2010; Virtanen et al., 2014). Sethi & Scales (2020) carried out a study with high school students in the United States. Their results evidenced that teacher and parental support were highly relevant to increase academic motivation and, indirectly, academic results. However, although it benefits the school climate, peer support has no statistically significant effect on academic motivation. We should bear in mind that the results of studies that consider peer support as the only source of academic support and those that include other sources of support may vary significantly, because the former do not control for the effect of parental and teacher support. The negative influence of peer support on academic motivation might be possible in a context where a general atmosphere of disruptive attitudes among peers is generated and tolerated (Mathys et al., 2013; Rubin et al., 2007).

In summary, in this current work the PASQ showed adequate psychometric properties that support its use in future research. Because of its relationship with academic motivation, this instrument will likely be useful to help detect students with inadequate support (i.e., low levels of teacher or parental support), to help prevent future difficulties in academic achievement. This is of special interest for those contexts in which students’ have poor levels of academic achievement, such as the one under study, the Dominican Republic. The Dominican Republic has repeatedly shown low levels of academic success when compared to other countries (i.e., OECD, 2019). With the assessment of academic support, we would be able to detect those adolescents who may have lower academic motivation and, therefore, problems with academic achievement. The puzzle of academic achievement is greater than a measurement scale, but every piece is welcomed to accomplish the goal.

It is important to note the limitations of this work. For example, because of the cross-sectional design of this research, we were unable to test the longitudinal invariance of the PASQ. This aspect could be examined in future studies to test the adequacy of the instrument to assess changes in academic support over time. Additionally, these current results were limited to the context of the Dominican Republic, a country that has repeatedly shown low levels of academic success relative to other countries (OECD, 2019). Indeed, only students from two districts participated, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Therefore, analysis of its performance in other cultures, languages, and education systems would be recommended in order to generalize the results to other countries. Additionally, a limitation of the scale is its self-assessment format which could be influence for social desirability and student’s response styles.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acción Empresarial para la Educación, EDUCA. (2015). Informe de progreso educativo [Educational progress report]. EDUCA.

Al-Alwan, A. (2014). Modeling the relations among parental involvement, school engagement and academic performance of high school students. International Education Studies, 7(4), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n4p47.

Alfaro, E. C., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2015). The longitudinal relation between academic support and Latino adolescents’ academic motivation. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986315586565.

Alfaro, E. C., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Bámaca, M. Y. (2006). The influence of academic support on Latino adolescents’ academic motivation. Family Relations, 55(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00402.x.

Archer, C. M., Jiang, X., Thurston, I. B., & Floyd, R. G. (2019). The differential effects of perceived social support on adolescent hope: testing the moderating effects of age and gender. Child Indicators Research, 12(6), 2079–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-9628-x.

Arora, P. G., Wheeler, L. A., Fisher, S., & Barnes, J. (2017). A prospective examination of anxiety as a predictor of depressive symptoms among Asian American early adolescent youth: The role of parent, peer, and teacher support and school engagement. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000168.

Boudreau, D., Santen, S. A., Hemphill, R. R., & Dobson, J. (2004). Burnout in medical students: examining the prevalence and predisposing factors during the four years of medical school. Annuals of Emergency Medicine, 44(4), 575–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.07.248.

Boudreault-Bouchard, A. M., Dion, J., Hains, J., Vandermeerschen, J., Laberge, L., & Perron, M. (2013). Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress: results of a four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 36(4), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.002.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development, 6, 187–249.

Cattley, G. (2004). The impact of teacher-parent-peer support on students’ well-being and adjustment to the middle years of schooling. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 11(4), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2004.9747935.

Chen, J. J. L. (2005). Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to Hong Kong adolescents’ academic achievement: the mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(2), 77–127. https://doi.org/10.3200/mono.131.2.77-127.

Chiu, M. M., & Chow, B. W. Y. (2011). Classroomdiscipline across 41 countries: school, economic, and cultural differences. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 42, 516–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110381115.

Choe, D. (2020). Parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental support as predictors of adolescents’ academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105172 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105172.

Ciarrochi, J., Morin, A. J., Sahdra, B. K., Litalien, D., & Parker, P. D. (2017). A longitudinal person-centered perspective on youth social support: relations with psychological wellbeing. Developmental Psychology, 53(6), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000315.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

Clark, K. N., Dorio, N. B., Eldridge, M. A., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2020). Adolescent academic achievement: a model of social support and grit. Psychology in the Schools, 57(2), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22318.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309.

Estell, D. B., & Perdue, N. H. (2013). Social support and behavioral and affective school engagement: The effects of peers, parents, and teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21681.

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148.

Gutiérrez, M., Tomás, J. M., Romero, I., & Barrica, J. M. (2017). Apoyo social percibido, implicación escolar y satisfacción con la escuela. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 22(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2017.01.001.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. Pianta, M. Cox & K. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (pp. 49–84). Baltimore: Brookes. pp..

Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., Cappella, E., Atkins, M., Rivers, S. E., Brackett, M. A., & Hamagami, A. (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113(4), 461–487.

Horanicova, S., Husarova, D., Madarasova Geckova, A., De Winter, A. F., & Reijneveld, S. (2022). Family socioeconomic status and adolescent school satisfaction: does schoolwork support affect this association?. Frontiers in Psychology, 1343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841499

Horanicova, S., Husarova, D., Madarasova Geckova, A., Klein, D., van Dijk, J. P., de Winter, A. F., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2020). Teacher and classmate support may keep adolescents satisfied with school and education. Does gender matter? International Journal of Public Health, 65(8), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01477-1.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Iniciativa Dominicana por una Educación de Calidad, IDEC. (2014). Informe anual de seguimiento y monitoreo [Annual follow-up and monitoring report]. Iniciativa Dominicana por una Educación de Calidad (IDEC). https://doi.org/10.22206/cys.2014.v39i1.pp9-32

Isik, U., Tahir, O. E., Meeter, M., Heymans, M. W., Jansma, E. P., Croiset, G., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2018). Factors influencing academic motivation of ethnic minority students: a review. Sage Open, 8(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018785412.

Jelas, Z. M., Azman, N., Zulnaidi, H., & Ahmad, N. A. (2016). Learning support and academic achievement among Malaysian adolescents: the mediating role of student engagement. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-015-9202-5.

Lam, S. F., Jimerson, S., Kikas, E., Cefai, C., Veiga, F. H., Nelson, B., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Liu, Y., Negovan, V., Shin, H., Stanculescu, E., Wong, B. P. H., Yang, H., & Zollneritsch, J. (2012). Do girls and boys perceive themselves as equally engaged in school? Theresults of an international study from 12 countries. Journal of School Psychology, 50(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.004.

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Chiu, M. M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02288.

Leung, G. S., Yeung, K. C., & Wong, D. F. (2010). Academic stressors and anxiety in children: the role of paternal support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9288-4.

Li, Y., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). Personal and ecological assets and academic competence in early adolescence: The mediating role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 801–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9535-4.

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Marengo, D., & Settanni, M. (2016). Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high school. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01988.

Maiuolo, M., Deane, F. P., & Ciarrochi, J. (2019). Parental authoritativeness, social support and help-seeking for mental health problems in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00994-4.

Malecki, C. K. & & Demaray, M. K. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS. Psychology in the Schools, 39(1), 1–18..

Malecki, C. K., & Elliott, S. N. (1999). Adolescents’ ratings of perceived social support and its importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools, 36(6), 473–483.

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., Elliott, S. N., & Nolten, P. W. (1999). The Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of educational research, 79(1), 327–365. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325583.

Mathys, C., Hyde, L. W., Shaw, D. S., & Born, M. (2013). Deviancy and normative training processes in experimental groups of delinquent and nondelinquent male adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 39(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21456.

Mazer, J. P., & Thompson, B. (2011). The validity of the Student Academic Support Scale: Associations with social support and relational closeness. Communication Reports, 24(2), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2011.622237.

Mazer, J. P., & Thompson, B. (2016). Parental academic support: a validity report. Communication Education, 65(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1081957.

Mikami, A. Y., Ruzek, E. A., Hafen, C. A., Gregory, A., & Allen, J. P. (2017). Perceptions of relatedness with classroom peers promote adolescents’ behavioral engagement and achievement in secondary school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(11), 2341–2354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0724-2.

Miller, A., Ferguson, E., & Byrne, I. (2000). Pupils’ causal attributions for difficult classroom behaviour. British Journal of Educational. Psychology, 70, 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709900157985.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nolten, P. W. (1994). Conceptualization and measurement of social support: The development of the student social support scale. Doctoral Dissertation: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

OECD (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do. PISA OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico, OECD. (2016). PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en

Plunkett, S. W., & Bámaca-Gómez, M. Y. (2003). The relationship between parenting, acculturation, and adolescent academics in Mexican-origin immigrant families in Los Angeles. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 222–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303025002005.

Ramos-Díaz, E., Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Fernández-Zabala, A., Revuelta, L., & Zuazagoitia, A. (2016). Adolescent students perceived social support, self-concept and school engagement. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 21(2), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1387/revpsicodidact.14848.

Raykov, T. (2004). Behavioral scale reliability and measurement invariance evaluation using latent variable modeling. Behavior Therapy, 35(2), 299–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(04)80041-8.

Raykov, T., Dimitrov, D. M., & Asparouhov, T. (2010). Evaluation of scale reliability with binary measures using latent variable modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(2), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511003659417.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2007). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.), & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol 3., 6th ed., pp. 571-645). New York: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1026//0942-5403.8.3.189

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000058.

Saleh, M. Y., Shaheen, A. M., Nassar, O. S., & Arabiat, D. (2019). Predictors of school satisfaction among adolescents in Jordan: A cross-sectional study exploring the role of school-related variables and student demographics. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 12, 621–631. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.s204557.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2012). The schoolwork engagement inventory: energy, dedication and absorption (EDA). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000091.

Sands, T., & Plunkett, S. W. (2005). A new scale to measure adolescent reports of academic support by mothers, fathers, teachers, and friends in Latino immigrant families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27(2), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986304273968.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2009). Social support: Mapping the construct. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(1), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509105526.

Sethi, J., & Scales, P. C. (2020). Developmental relationships and school success: How teachers, parents, and friends affect educational outcomes and what actions students say matter most. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101904 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101904.

Shen, J., Washington, A. L., Palmer, L. B., & Xia, J. (2014). Effects of traditional and non-traditional forms of parental involvement on school-level achievement outcome: An HLM study using SASS 2007-2008. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(4), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.823368.

Smokowski, P. R., Bacallao, M. L., Cotter, K. L., & Evans, C. B. (2015). The effects of positive and negative parenting practices on adolescent mental health outcomes in a multicultural sample of rural youth. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0474-2.

Song, J., Bong, M., Lee, K., & Kim, S. I. (2015). Longitudinal investigation into the role of perceived social support in adolescents’ academic motivation and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000016.

Tardy, C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. American journal of community psychology, 13(2), 187–202.

Thompson, B., & Mazer, J. P. (2009). College student ratings of student academic support: Frequency, importance, and modes of communication. Communication Education, 58(3), 433–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520902930440.

Thompson, B., & Mazer, J. P. (2012). Development of the parental academic support scale: Frequency, importance, and modes of communication. Communication Education, 61(2), 131–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2012.657207.

Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Pastor, A. M., & Sancho, P. (2020). Perceived Social Support, School Adaptation and Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being. Child Indicators Research, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09717-9.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Tinga, F., & Ormel, J. (2010). Truancy in late elementary and early secondary education: The influence of social bonds and self-control — The TRAILS study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(4), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409347987.

Virtanen, T. E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Kuorelahti, M. (2014). Student behavioral engagement as a mediator between teacher, family, and peer support and school truancy. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.09.001.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x.

Wentzel, K. R., Russell, S., & Baker, S. (2016). Emotional support and expectations from parents, teachers, and peers predict adolescent competence at school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000049.

WestEd (2000). California Healthy Kids Survey. Los Alamitos, CA: WestEd.

Yang, H. J. (2004). Factors affecting student burnout and academic achievement in multiple enrollment programs in Taiwan’s technical-vocational colleges. International Journal of Educational Development, 24(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.12.001.

Acknowledgements

Betty Reyes was beneficiary of the grant: Beca para Jóvenes Investigadores 2019 de Países en Vías de Desarrollo del Programa de Cooperación 0’7 para el año 2018, Vicerrectorado de Internalización y Cooperación (University of Valencia). Sara Martínez-Gregorio is a researcher beneficiary of the FPU program from the Ministry of Universities (FPU18/03710).

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The survey procedure meets the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (APA) and it received the ethics approval of the Ministry of Education of the Dominican Republic.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reyes, B., Martínez-Gregorio, S., Galiana, L. et al. Validation of Perceived Academic Support Questionnaire (PASQ): a study using a sample of Dominican Republic high-school students. J Child Fam Stud 31, 3425–3434 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02473-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02473-0