Abstract

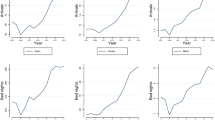

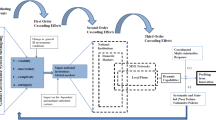

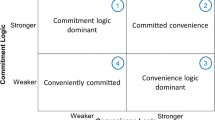

This study assesses the 1951 Toho–Subaru antitrust merger case in the Japanese movie theater market. Using information regarding the location of theaters in the Tokyo metropolitan area, I examined the relationship between the number of attendees and the structure of the local market competition: a regression equation relating to the number of attendees and the local market structure was derived from a model of product differentiation, which incorporated the features of a movie theater market. The results revealed that nearby rival theaters had negative effects on other theaters’ attendance numbers, and these effects did not dissipate even where there was 10 km between each theater. Based on empirical results, it appears that the Tokyo High Court and the competition agency defined the geographic movie theater market as being smaller than it actually was. The results of this study suggest that the application of econometric analysis, combining geographic information, is useful in merger reviews of retail industries, such as movie theaters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Antimonopoly Act (AMA) prohibits stockholdings (Article 10), interlocking directors (Article 13), mergers (Article 15), and the acquisition of businesses (Article 16) if such business combinations have anticompetitive effects.

White (2008) pointed out the importance of follow-up studies regarding past merger cases.

The guidelines were revised in 2007. The main points of the revision included the following: (1) concepts of the small but significant nontransitory increase in price (SSNIP) test of market definition and the international market were explicitly incorporated into a merger review; (2) the Hirschman–Herfindahl index was adopted as a threshold of the safe harbor rule; (3) the criteria for assessment of competitive pressure from import, entry, and customers were revised; and (4) structural merger remedies were principally applied. For more details, see Kawahama et al. (2008).

See Sections 2–3 of JFTC (2007).

For more details, see Kisugi (1999).

While the GHQ/SCAP regarded the zaibatsu as anticompetitive devices, there was some debate regarding the role of the zaibatsu. Frankl (1999) showed that although the earnings of new zaibatsu firms were higher, faster growing, and less variable than independent firms, the only significant difference between old zaibatsu and independent firms was that the earnings of the old zaibatsu firms were less stable. Okazaki (2001) examined the role of zaibatsu holding companies from an efficiency perspective in corporate governance in the prewar period and found that the zaibatsu affiliates significantly outperformed other companies. For more detail on prewar and wartime Japanese firms, see Okazaki (1993).

As of September 2011, Toho and Subaru were still registered as operating companies.

Chapter 4 of the AMA provides that, if certain conditions are met, every merging corporation shall notify the JFTC in advance of their plan with regard to such a merger. For further details, see Hayashi (2008).

These four theaters were excluded because the first two were not regular movie theaters and the remaining two were located some distance from Subaru Za and Orion Za.

A further theater, Shibuya Toho, was outside the Ginza area.

Toho argued that Meiji Za and Kabuki Za, which were under reconstruction, should have been included in the market, as should have the four theaters excluded by the JFTC.

The Tokyo High Court ruled that the joint administrative agreement between Toho and Subaru was a type of leasing contract that enabled Toho to control Subaru’s businesses.

The eight theaters were Mita Eiga Za, Bunkyo Eiga Gekijo, Nishi Koyama Bunka Gekijo, Mukojima Kan, Tamanoi Eiga Gekijo, Tachibana Eiga Gekijo, Ekoda Bunka Gekijo, and Ohizumi Kaikan.

This has been illegal in the United States since the Paramount ruling. Chapter seven of De Vany (2004) is a detailed review of the Paramount case, and Gil (2010) empirically investigated the ruling. The JFTC also concerned block bookings in the movie industry, and some distributors voluntarily switched to a free booking system (Jiji Tsushin-sha 1951, 1952). However, in the end, the business practice was not ruled unlawful, and some studios, for example Shochiku (until 1999), Toei, and Toho, continued to use block booking (Kinema Junpo Film Institute 2005).

The true meanings of some abbreviations in the original document are difficult to understand without sufficient explanatory notes. For example, I can only infer that “Eastern” stands for films produced and distributed by the USSR or China. However, it is not necessary to know the exact meanings of the abbreviations as it is the differences among the theaters’ showings of the program patterns that is of interest here.

For further details regarding CMPE, see Kitamura (2010).

This study considers that “Daiei and Tokyo Eiga Haikyu” and “Tokyo Eiga Haikyu and Daiei” represent different patterns of film origins, because it is possible to infer that in the former a theater generally showed only Daiei films, whereas another theater in the latter category generally only screened films distributed by Tokyo Eiga Haikyu.

The Geocoding Tools & Utilities website (http://newspat.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/geocode/) was used to produce a file that adds a geocode to the original address data-file. As the data source is old and the designations of some theater addresses have changed over the years, there will be noise in the estimated distance.

The NAVITIME website (http://www.navitime.co.jp/) was used to report the travel distance between two given addresses.

The present specification assumes that theater characteristics (z j ) do not affect the number of films screened in each theater. A possible alternative specification could linearly include z j : \( \ln (R_{j} ) = \lambda_{1}^{\prime } {\text{own}}_{j} + \lambda_{2}^{\prime } {\text{rival}}_{j} + z_{j} \psi + \tau_{j} + \omega_{j} \). However, this does not change the final reduced-form regression equation, although the reduced-form coefficient of z j is σ −1(β − αη) + ψ rather than σ −1(β − αη).

Population data for each ward of the Tokyo metropolitan area were taken from the General Administrative Agency of the Cabinet (1953).

Einav (2007) pointed out large seasonal fluctuations in box office revenues in the US movie industry.

The first-stage regression results are provided in Sunada (2009).

One of the reasons for the imprecise estimates for own theater counts is that there is a very small variation in the own theater count because most theaters were independent (see Table 4).

References

ABA Section of Antitrust Law. (2005). Econometrics: Legal, practical, and technical issues. Chicago: American Bar Association.

Ackerberg, D. A., & Rysman, M. (2005). Unobserved product differentiation in discrete-choice models: Estimating price elasticities and welfare effects. RAND Journal of Economics, 36(4), 771–788.

Ashenfelter, O., Ashmore, D., Baker, J. B., Greason, S., & Hosken, S. (2006). Empirical methods in merger analysis: Econometric analysis of pricing in FTC v. Staples. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 13(2), 265–279.

Baker, J. B. (1999). Econometric analysis in FTC v. Staples. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 18(1), 11–21.

Berry, S. (1994). Estimating discrete-choice models of product differentiation. RAND Journal of Economics, 25(2), 242–262.

Berry, S., Levinsohn, J., & Pakes, A. (1995). Automobile prices in market equilibrium. Econometrica, 63(4), 841–890.

Chisholm, D. C., McMillan, M. S., & Norman, G. (2010). Product differentiation and film-programming choice: Do first-run movie theaters show the same films? Journal of Cultural Economics, 34(2), 131–145.

Chisholm, D. C., & Norman, G. (2012). Spatial competition and market share: An application to motion pictures. Journal of Cultural Economics. doi:10.1007/s10824-012-9168-4

Chung, W., & Kalnins, A. (2001). Agglomeration effects and performance: A test of the Texas lodging industry. Strategic Management Journal, 22(10), 969–988.

Dalkir, S., & Warren-Boulton, F. R. (2009). Prices, market definition, and the effects of merger: Staple-Office Depot (1997). In J. E. Kwoka Jr. & L. J. White (Eds.), The antitrust revolution: Economics, competition, and policy (5th ed., pp. 178–199). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davis, P. (2005). The effect of local competition on retail prices: The US motion picture exhibition market. Journal of Law and Economics, 48(2), 677–708.

Davis, P. (2006a). Measuring the business stealing, cannibalization and market expansion effects of entry in the US motion picture exhibition market. Journal of Industrial Economics, 54(3), 293–321.

Davis, P. (2006b). Spatial competition in retail markets: movie theaters. RAND Journal of Economics, 37(4), 964–982.

De Vany, A. (2004). Hollywood economics: How extreme uncertainty shapes the film industry. Abingdon: Routledge.

Einav, L. (2007). Seasonality in the US motion picture industry. RAND Journal of Economics, 38(1), 127–145.

Frankl, J. (1999). An analysis of Japanese corporate structure, 1915–1937. Journal of Economic History, 59(4), 997–1015.

Gaynor, M., & Vogt, W. (2003). Competition among hospitals. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(4), 764–785.

General Administrative Agency of the Cabinet. (1953). Showa 25 nen kokusei chosa hokokku (Population census of 1950) Report by prefecture, Vol. VII, part 13: Tokyo-to. Tokyo (in Japanese).

Gil, R. (2010). An empirical investigation of the Paramount antitrust case. Applied Economics, 42(2), 171–183.

Hayashi, S. (2008). Merger regulation in the antimonopoly law. Nagoya Journal of Law and Politics, 224, 21–117.

IKAROS Publications. (2011). Toden no 100-nen: Since 1911 (100 years of the Toden streetcars: Since 1911). Tokyo: IKAROS Publications.

Inoue, A. (2007). Japanese Antitrust Law Manual: Law, Cases and Interpretation of the Japanese Antimonopoly Act, International Competition Law Series 27. Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Japan Fair Trade Commission. (1951). Toho kabushiki kaisha no ken (the case of Toho, Co.): Showa 25 nen (han) 10 go. Shinketsushu (JFTC Decision Report), 2, 321–328 (in Japanese).

Japan Fair Trade Commission. (1952). Toho kabushiki kaisha no ken (the case of Toho, Co.): Showa 25 nen gyo (na) 21 go, Shinketsushu (JFTC Decision Report), Appendix 1, 3, 635–657 (in Japanese).

Japan Fair Trade Commission. (2007). Guidelines to application of the antimonopoly act concerning review of business combination.

Jiji Tsushin-sha. (1951, 1952, 1954). Eiga nenkan (Jiji motion picture almanac), Tokyo (in Japanese).

Kalnins, A. (2006). Markets: The US lodging industry. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4), 203–218.

Kawahama, N., Sensui, F., Takeda, K., Miyai, M., Wakui, M., Ikeda, C., & Hayashi, S. (2008). Kigyo Ketsugo Gaidorain no kaisetsu to bunseki (Merger and acquisition guidelines: Examination and analysis). Tokyo: Shojihomu (in Japanese).

Kinema Junpo Film Institute. (2005). Eiga Produsa no Kiso Chishiki (A Basic Guide for the Producer). Tokyo: Kinema Junpo (in Japanese).

Kisugi, S. (1999). Nihon no Kyoso Seisaku no Rekishiteki Gaikan (I) (the History of the Japanese Competition Policy (I)). In A. Goto & K. Suzumura (Eds.), Nihon no Kyoso Seisaku (Competition Policy in Japan), Chapter 2 (pp. 17–44). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press (in Japanese).

Kitamura, H. (2010). Screening enlightenment: Hollywood and the cultural reconstruction of defeated Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kouga, C. (Ed.). (2008). Bukka no Bunka-shi Jiten (Cultural and Historical Encyclopedia of Prices). Tokyo: Tenbosha (in Japanese).

Manuszak, M. D., & Moul, C. C. (2008). Prices and endogenous market structure in office supply superstores. Journal of Industrial Economics, 50(1), 94–112.

Motta, M. (2004). Competition policy: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Okazaki, T. (1993). The Japanese firm under the wartime planned economy. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 7(2), 175–203.

Okazaki, T. (2001). The role of holding companies in pre-war Japanese economic development: Rethinking Zaibatzu in perspectives of corporate governance. Social Science Japan Journal, 4(2), 243–268.

Orbach, B. Y., & Einav, L. (2007). Uniform prices for differentiated goods: The case of the movie-theater industry. International Review of Law and Economics, 27(2), 129–153.

Pinkse, J., Slade, M. E., & Brett, C. (2002). Spatial price competition: A semiparametric approach. Econometrica, 70(3), 1111–1153.

Sato, T. (2006). Nihon Eiga Shi (History of Japanese Movies) 2: 1941–1959 (an augmented edition). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten (in Japanese).

Smith, H. (2004). Supermarket choice and supermarket competition in market equilibrium. Review of Economic Studies, 71(1), 235–263.

Sunada, M. (2009). An empirical investigation of the toho-subaru antitrust case: A merger case in the Japanese movie theater market. CPRC Discussion Paper Series, CPDP-43-E.

Thomadsen, R. (2005). The effect of ownership structure on price in geographically differentiated industries. RAND Journal of Economics, 36(4), 908–929.

Warren-Boulton, F. R., & Dalkir, S. (2001). Staples and Office Depot: An event probability case study. Review of Industrial Organization, 19(4), 467–479.

Watson, R. (2009). Product variety and competition in the retail market for eyeglasses. Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(2), 217–251.

White, L. (2008). The role of competition policy in the promotion of economic growth. NYU Law and Economics Research Paper Series; No. 08-23.

Yomota, I. (2000). Nihon Eiga Shi 100-nen (100 years of Japanese Movies). Tokyo: Shueisha (in Japanese).

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this study were presented at the AsLEA Annual Meeting, the EARIE, Hitotsubashi University, the IIOC, the JEA Annual Meeting, the JFTC, Kyushu University, Kwansei Gakuin, and Nihon University. I would like to express sincere gratitude to the editor, two anonymous referees, and various seminar attendees for their useful comments and suggestions. The financial supports from the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) and the Okawa Foundation are gratefully acknowledged. Needless to say, all remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sunada, M. Competition among movie theaters: an empirical investigation of the Toho–Subaru antitrust case. J Cult Econ 36, 179–206 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9164-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9164-8