Abstract

Microalgal polysaccharides have been reported in many studies due to their uniqueness, biocompatibility, and high value, and Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 was an excellent source of polysaccharides and β-glucans. However, the polysaccharides from the red unicellular alga Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 have barely been studied. In this work, hot water extraction of Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 polysaccharides (RSP) was optimized using response surface methodology (RSM) based on Box–Behnken design (BBD). The maximum RSP yield (9.29%) was achieved under the optimum extraction conditions: liquid–solid ratio of 50.00 mL g−1; extraction temperature of 84 °C; extraction time of 2 h; and extraction times of 5 times. The results of physicochemical characterization showed that RSP had high sulfate and uronic acid with content of 19.58% and 11.57%, respectively, rough layered structure, and mainly contained glucose, galactose, xylose, and galacturonic acid with mass percentages of 34.08%, 28.70%, 12.46%, and 12.10%. Furthermore, four kinds of antioxidant assays were carried out, and the results indicated that RSP had strong scavenging activities on ABTS and hydroxyl radical and moderate scavenging activities on DPPH and ferrous chelating ability. These results indicated that RSP showed potential as a promising source of antioxidants applied in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oceans, with total planetary coverage of 70%, possess high biodiversity and are habitats for a large number of seaweeds and microalgae (Gaignard et al. 2019). Marine microalgae can produce easily modified, biocompatible, stable biodegradable, non-toxic, and highly safe biological-active compounds, such as polysaccharides, carotenoids, proteins, peptides, essential fatty acids, vitamins, and mineral oxides; hence, it has been identified as an expected supplement in the fields of biochemistry, biomass energy resources, and pharmacology (Raposo et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2019). In particular, some unique polysaccharides exclusively present in rhodophytes and numerous bioactive properties such as anti-tumor, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antiviral, anticoagulant, and immunomodulatory effects of polysaccharides have been reported (Raposo et al. 2014; Fleita et al. 2015). Rhodosorus belongs to the division Rhodophyta or red algae and studies have mainly focused on the extraction and purification of phycoerythrin from the algal cells. The existing research shows that Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 is rich in polysaccharides and its content was maximized up to 242.6 mg L−1 day−1 (Dai et al. 2020), which is much higher than the polysaccharide productivity of Porphyridium cruentum (Sun et al. 2008). In addition, Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 with high biomass was considered as an optimal feedstock for the production of bioethanol and β-glucans (Dai et al. 2020). However, there are still no studies focusing on the extraction, physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant activity of Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 polysaccharides (RSP).

The selection of a suitable extraction method is a crucial step in the extraction of polysaccharides from raw materials, because this decision may affect the yield, composition, structure, and integrity of bioactive polysaccharides (Alboofetileh et al. 2019a). There are various methods available for the extraction of polysaccharides, including hot water, dilute acid, dilute alkali, microwave, ultrasonic, and enzyme extractions (Ardiles et al. 2020). Generally, hot water extraction is the most common method for extracting polysaccharides with the advantages of low cost, simple operation, no special equipment required, excellent quality of final product, and most suitable for preparation of neutral and acidic polysaccharides (Dong et al. 2016). In addition, hot water extraction is an important technology from an industrial point of view. The yield of this method largely depends on a liquid-to-solid ratio, extraction time, extraction temperature, and extraction times (Li et al. 2019b). Yu used response surface methodology (RSM) to optimize the extraction process of Angelica sinensis polysaccharides (ASP), and the water–solid ratio and the extraction time were found to be the most important factors (Yu et al. 2013). The optimal procedure is shown as follows: water–solid ratio was 5 mL g−1, extraction time was 130 min, and extraction number was 5. According to Ai et al. (2013), the extraction process of ASP was optimized by an orthogonal experimental design, and the extraction yield of ASP was 5.6% under the optical extraction condition (water–solid ratio 6 mL g−1, extraction time 180 min, extraction temperature 100 °C, and extraction times 4). Therefore, it is very important to optimize the extraction conditions of RSP for its future research, development and industrial application. RSM is a set of statistical and computational techniques that are composed of experiment designing, model building, evaluation of factors, and search for optimal conditional factors (Golbargi et al. 2021). RSM is often used to determine the influence of each factor and its interaction on the extraction rate and identify the optimal conditions statistically. Furthermore, this model-based approach not only reduces the number of experiments but also greatly reduces development time and overall cost.

Polysaccharides have gained much research interest in health food, new drugs, and cosmetics, as gelling agents, thickeners, emulsifiers, and stabilizers that have been attributed to their chemical structures and biological activities. It has been proved that sulfated polysaccharides have shown promising inhibitory effects on preventing recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Hans et al. 2020; Pereira and Critchley 2020). In addition, the antioxidant activity is one of the most studied aspects of polysaccharides. Natural polysaccharides isolated from Porphyra/Pyropia, Eucheuma, Kappaphycus, and Gracilaria have strong free radical scavenging activities and unique properties to prevent oxidative damage in living organisms (Aziz et al. 2020). Based on the literature reports, biological activities of polysaccharides vary with their physical–chemical structural features such as physical appearance, the ratio of constituent monosaccharides, and degree of sulfation (Venkatesan et al. 2019). For example, Chlorella pyrenoidosa polysaccharides (CPP) using 60%, 70%, and 85% final ethanol concentrations for precipitation were called CPP60, CPP70, and CPP85, respectively. All of them possessed antioxidant activity in vitro, but CPP70 exhibited stronger scavenging activity against superoxide, DPPH, and hydroxyl radicals compared with CPP60 and CPP85, which resulted from the differences of structural features and molecular size of polysaccharides (Chen et al. 2020). Similarly, Laminaria polysaccharide with higher uronic acid and sulfate content displayed stronger antioxidant activity (Bhadja et al. 2016). Yuan and Macquarrie (2015) also reported that the scavenging capacity to DPPH radical of polysaccharides extracted from Ascophyllum nodosum is proportional to their –SO3H content, i.e., the component with 28.60% –SO3H content has the highest scavenging capacity of about 15%, whereas the component with 7.82% –SO3H content only has a scavenging capacity of about 2%.

As far as we know, there have been no reports on Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 polysaccharides (RSP). Therefore, this is a systematic study to optimize the condition for maximizing the hot water extraction yield of RSP using RSM. The structural and morphological features of RSP were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and X-ray diffractometry (XRD). Besides, the antioxidant capacity of RSP was investigated via 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2-azino-bis 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS), hydroxyl radical scavenging, and ferrous chelating ability. These results provide a potential of polysaccharide from Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 in the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics industry as an antioxidant.

Materials and methods

Cultivation and collection of microalgae

Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 was isolated from Xisha Islands, South China Sea (111° 45.000′ E, 16° 28.471′ N). The species was identified according to the distinguishing morphological features, 18S rRNA gene sequences, and BLAST analysis reported previously (Dai et al. 2020). The strain was cultured in 1500-mL vertical bubble column photobioreactors (6.0 cm × 60 cm) containing seawater medium composed of 17.6 mM NaNO3; 0.69 mM K2HPO4·3H2O; 0.48 mM NaHCO3; 11.7 µM FeCl3·6H2O; 11.7 µM Na2EDTA·2H2O; 0.91 µM MnCl2·4H2O; 0.08 µM ZnSO4·7H2O; 0.04 µM CoCl2·6H2O; 0.04 µM CuSO4·5H2O; and 0.02 µM Na2MoO4·2H2O in 28‰ seawater (Li et al. 2019a). The cultures were incubated at 25 °C under continuous illumination with the light intensity gradually increased from 30 to 180 μmol photons m−2 s−1 in the first 4 days of cultivation and then kept at 180 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3214 × g for 5 min under the later stage of the exponential/linear phase and then washed twice with sterile deionized water, freeze-dried, ground into powder and stored before extraction (Fleita et al. 2015).

Hot water extraction of polysaccharides

RSP were extracted by a slight modification of the hot-water extraction method described by Khan et al (2019). Briefly, deionized distilled water was added to Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730, and the resultant solutions were kept at room temperature for 30 min before heat treatment in a water bath. A preliminary single-factor experiment was carried out at a liquid–solid ratio (20–60 mL g−1), extraction temperature (60–100 °C), extraction time (1–5 h), and extraction times (2–6 times), respectively. When measuring the effects of the liquid–solid ratio (20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 mL g−1) on the yield of the RSP, the extraction temperature was fixed at 90 °C, the extraction time was set to 2 h, and the extraction times was fixed at 3 times. When the effects of extraction temperature (60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 °C) on the RSP yield were determined, the liquid–solid ratio was set as 30 mL g−1, the extraction time was fixed at 2 h, and the extraction times was set to 3 times. When estimating the effects of extraction time (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h) on the yield of the RSP, the liquid–solid ratio, the extraction temperature, and the extraction times were fixed at 30 mL g−1, 90 °C, and 3 times, respectively. When assaying the effects of the extraction times (2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 times) on the yield of the RSP, the liquid–solid ratio, the extraction temperature and the extraction time were fixed at 30 mL g−1, 90 °C, and 2 h, respectively. After performing the extraction process, the crude extract was centrifuged at 8228 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. A rotary evaporator was employed to concentrate the filtrate equal to 1/4 of its original volume at 50 °C, followed by precipitation through the addition of threefold ethanol (95%) and then stored at 4 °C overnight. Twenty milliliter of 20% hydrogen peroxide was added to the precipitate collected by centrifugation (12,857 × g, 10 min), which were stirred in a water bath at 50 °C for 1 h, and then heated to remove hydrogen peroxide completely. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,857 × g for 10 min, dialyzed for 24 h (500 Da cutoff), and subsequently subjected to freeze-drying for 48 h to obtain RSP powder. Extraction yield (Y) was calculated by the following Eq. (1) (Li et al. 2021):

Experimental design and response surface modeling

According to the single-factor experiment results (Fig. S1), the Box-Behnken design (BBD) in the present study was a design of four variables: liquid–solid ratio (A) at 30, 40, and 50 mL g−1; extraction temperature (B) at 70, 80, and 90 °C; extraction time (C) at 1, 2, and 3 h; and extraction times (D) at 3, 4, and 5 times. Each variable had three different levels (− 1, 0, 1). The extraction yield of RSP was used as the dependent variable. The whole design contains 27 experimental runs, which were represented by the coded and non-coded values of the experimental variables as shown in Table 1. The experiment was carried out in random order. The mutual interaction among the variables and their corresponding optimum levels were expressed by a second-order polynomial equation (Awatief et al. 2016). Furthermore, three additional confirmation extraction experiments under the optimal conditions were carried out to verify the accuracy of the statistical experimental strategies (Shang et al. 2021).

Physicochemical characterization of RSP

Chemical composition analysis

The content of total sugar was determined according to the method of phenol–sulfuric acid using glucose as a standard (Li et al. 2020). Bicinchonininc acid (BCA) protein colorimetry was used to measure the protein content of RSP (Khan et al. 2020). The sulfate content of RSP was analyzed by the BaCl2-gelatin turbidity method of Bhadja et al (2016) with some modifications. Briefly, about 10 mg of RSP sample and K2SO4 standard were solubilized in 5 mL of 4 M HCl, hydrolyzed at 90 °C for 2.5 h. The hydrolyzed samples (0.1 mL) were pipetted into 5-mL centrifuge tubes, to which 1.9 mL of 3% TCA and 0.5 mL of BaCl2-gelatin reagent were added. The released barium sulfate suspension was measured at λ = 360 nm. Based on a K2SO4 calibration curve (0.52–200 mg mL−1), the sulfate content of RSP was quantified. The uronic acid content of RSP was measured by the meta-hydroxydiphenyl assay method with modification (Hui et al. 2019; Hao et al. 2020). RSP were dissolved in water at a concentration of 0.1 mg mL−1, and different concentrations (0, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, and 0.08 mg mL−1) of the standard, galacturonic acid (GalA) were also prepared. A total of 0.5 mL of sample and standard were mixed with 3 mL of sodium tetraborate sulfuric acid solution (0.0125 mol L−1), heated at 90 °C for 15 min, and then cooled down in an ice bath to terminate the reaction. Finally, 50 uL of meta-hydroxydiphenyl solution (0.15%) was accurately added and mixed and kept at room temperature for 40 min. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm. The contents of uronic acids in samples could be calculated according to the standard curve. Total phenolic content (TPC) of RSP was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent assay (Foo et al. 2017). Based on a gallic acid calibration curve, the TPC was determined and indicated as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per g dry biomass (Almendinger et al. 2021).

Monosaccharide composition

Ion chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was applied to analyze the monosaccharide composition of RSP with 13 standard monosaccharides (fucose, rhamnose, arabinose, galactose, glucose, xylose, mannose, fructose, ribose, galacturonic acid, glucuronic acid, mannuronic acid and guluronic acid). Five mg of polysaccharide sample was accurately weighed, and 1 mL TFA acid (2.5 M) solution was added and heated at 121 °C for 2 h, followed by drying under nitrogen. Methanol was added to clean it and then dried under nitrogen. The methanol cleaning step was repeated 2–3 times. The sample was then dissolved in sterile water and transferred to the chromatographic flask for testing. An electrochemical detector was employed to detect the monosaccharide components. Mobile phase A was 0.1 M NaOH, and the mobile phase B was 0.1 M NaOH and 0.2 M NaAC. With 5 μL of injection volume, the samples were analyzed on a Dionex CarboPac PA10 column (250 × 4.0 mm, 10 um) at 30 °C with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1.

SEM

The surface characterization and microstructure evaluation of RSP were observed by SEM (Sigma 300/VP, Zeiss) at a voltage of 3.0 kV and under 10,000 × and 50,000 × magnification, respectively. Freeze-dried RSP samples were attached to specimen holders with double-sided carbon tape and then sputtered with gold for analysis under a high-vacuum chamber (Liu et al. 2020).

AFM

A scanning probe microscope (Nano Man VS) was used for AFM analysis of RSP. The RSP sample was placed in distilled water (1 µg mL−1) and sonicated for 30 min. After sonication, 2–3 µL of RSP solution was pipetted onto mica disc which was subsequently dried at 120 °C for 0.5 min before analysis (Khan et al. 2020).

XRD

XRD analyses were carried out at room temperature with Cu Kα radiation on a MXP18 HF diffractometer (MAC Science Co., Japan). The patterns were collected between 10 and 90° at a scan rate of 10.0° min−1.

FT-IR

FT-IR (IR Affinity-1, Japan) was used to analyze the functional chemistry of RSP. Infrared spectroscopy of the sample was recorded at the frequency of 400–4000 cm−1 at a resolution ratio of 1 cm−1, and the scan number was 32 (Guidara et al. 2021).

Antioxidant activities of RSP

DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

The free-radical scavenging capacity of RSP was analyzed using the DPPH test based on Venkatesan et al. (2019). Briefly, 100 uL of 0.1 mM DPPH methanolic solution was added to the 100 uL RSP of different concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg mL−1). The solution was vortexed for 1 min and kept at room temperature for 30 min in the dark, and the absorbance at 517 nm was measured by a micro-plate reader. Ascorbic acid was used as reference standard. The ability to scavenge the DPPH radical was calculated as follows:

Here, DPPH solution plus RSP sample was used as Asample, RSP sample without DPPH solution was used as Asample blank, and DPPH solution without RSP sample was used as Acontrol.

ABTS radical scavenging activity assay

ABTS radical scavenging activity was measured by the method of Liu et al. (2015). ABTS radical cation solution was prepared by 12–16 h reaction of ABTS (7.4 mM) with potassium persulfate (2.6 mM) at room temperature in dark. The solution was diluted with H2O by 20.3 times to obtain an absorbance of 0.700 at 734 nm. 0.2 mL samples of different concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg mL−1) were mixed with the diluted ABTS (0.8 mL). The mixture was shaken for 10 s and let stand for 6 min. The absorbance at 734 nm was measured with a micro-plate reader. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The activity to scavenge ABTS radical was calculated with the formula below:

where Asample contains ABTS solution and RSP solution, Asample blank contains RSP solution and H2O, and Acontrol contains ABTS solution and H2O.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay was done as previously described with some modifications (Chen et al. 2016). A total of 1.0 mL of 9.0 mM FeSO4 and 1.0 mL of 9.0 mM ethanol salicylate were added to 1.0 mL of polysaccharide solution in 5-mL test tubes, and 1.0 mL of 9.0 mM H2O2 was added. The reaction was carried out in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 510 nm. Each polysaccharide sample and the positive control (Vc) had five concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg mL−1). The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

where Asample is the absorbance of the RSP sample, Asample blank is the absorbance of the reagent blank (water instead of H2O2), and Acontrol is the absorbance of the blank without the RSP sample.

Ferrous ion chelating activity assay

The iron chelating properties of RSP were determined according to Alencar et al. (2019). Briefly, 0.05 mL of 2 mM FeCl2, 0.5 mL sample of RSP at different concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg mL−1), and 0.1 mL of 5 mM ferrozine were mixed. The mixtures were vortexed for 1 min and reacted 10 min before measuring at 562 nm. EDTA-2Na was used as standard. The chelating ability of ferrous ion was calculated by the following formula:

where Asample stands for the absorbance of the reaction mixture, Asample blank stands for reagents without the RSP sample, and Acontrol stands for the absorbance of the RSP sample without reagents.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Design-Expert Software (8.0.6) and IBM SPSS statistics 25 (SPSS Inc., USA) software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. The polysaccharides extraction experimental results are expressed as mean and standard deviations of triplicate experiments (n = 3). The experimental data of chemical composition and antioxidant activities of RSP are shown as mean and standard deviations of two independent biological replicates and three technical replicates. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Extraction optimization of RSP

Model fitting and statistical analysis

As shown in Table 1, a 27-run BBD was applied to investigate the combined effects of four independent variables on polysaccharide yield of Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730. The experimental results obtained based on BBD fit a second-order polynomial mathematical equation in the coded level as follows:\(\mathrm{Polysaccharide}\ \mathrm{yield}\left(\%\right)=0.57+1.45\mathrm{A}+0.51\mathrm{B}+0.14\mathrm{C}+1.05\mathrm{C}+1.05\mathrm{D}+0.005\mathrm{A}\mathrm{C}-0.67\mathrm{BC}-0.00025\mathrm{D}+0.26\mathrm{CD}+1.18{\mathrm{A}}^2-0.55\mathrm{B}-1.40{\mathrm{C}}^2-0.21{\mathrm{D}}^2\)

Table S1 shows the ANOVA results for the fitted quadratic polynomial model of extraction of RSP. The high F value (19.38) and the low P value (< 0.0001) of the model indicated the response surface quadratic model was significant. The values of the regression coefficient (R2), the value for the adjusted coefficient of determination (R2 adj) and coefficient of variation (CV) was 0.9576, 0.9082, and 9.81% respectively. “Adeq Precision” measures the signal-to-noise ratio, and a ratio greater than 4 is desirable. The ratio of 17.521 indicates an adequate signal that means this model can be used to navigate the design space. The significance of each coefficient was checked using F value and P value. In the current study, it could be seen that the regression coefficients (A, D, A2, and C2) exhibited a highly significant effect (P < 0.001) and the regression coefficients (B, BC, and B2) were significant effects (P < 0.05). The other term coefficients were insignificant (P > 0.05). The normality assumption was illustrated by constructing a normal probability plot of the residuals.

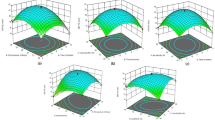

Effect of interacting variables

Three-dimensional response surface plots (Fig. 1) were established to illustrate the relationship between the independent variables and the response and the predicted optimal extraction parameters for maximizing the yield of RSP. The two-dimensional response surface plots (Fig. 2) also displayed modes of the regression equation in which an elliptical contour plot manifests the interactions are significant, and in turn, a circular contour plot means the interactions are negligible. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, interaction effects between liquid–solid ratio (A) and extraction temperature (B), liquid–solid ratio (A) and extraction time (C), liquid–solid ratio (A) and extraction times (D), extraction temperature (B) and extraction time (C), extraction temperature (B) and extraction times (D), and extraction time (C) and extraction times (D) were observed visually. When extraction time and extraction times were fixed at the zero levels, the polysaccharide yield increased at the beginning but then decreased with increasing liquid–solid ratio and extraction temperature. The liquid–solid ratio and extraction temperature belonged to insignificant interactions (Figs. 1a and 2a). Figures 1b and 2b described the extraction yield was not changed significantly by increasing the extraction time, but it increased as the ratio of water-to-raw-material increased under the zero level of extraction temperature and extraction times. Figures 1c and 2c showed the polysaccharide yields increased with enhanced liquid–solid ratio and extraction times but without significant effects. In Fig. 1d and 2d, the results suggested that extraction temperature and extraction time exerted a notable impact on polysaccharide yield. On the contrary, Figs. 1e and 2e indicated that the influence of extraction temperature and extraction times was not significant when liquid–solid ratio and extraction time was fixed at zero levels. Similarly, the mutual interaction between extraction time and extraction times was not significant on polysaccharide yield when liquid–solid ratio and the extraction temperature was fixed to be level 0 (Figs. 1f and 2f).

Optimization and model verification

The optimum extraction conditions were obtained by solving the regression equation using the Design-Expert Software, it was concluded that the optimal extraction conditions were as follows: liquid–solid ratio, 50 mL g−1; extraction temperature, 84.41 °C; extraction time, 2.04 h; and extraction times, 5 times. Under these optimal conditions, the maximum predicted extraction yield was 9.30%. Considering the operation in actual production, the adjusted optimum extraction conditions were as follows: liquid–solid ratio of 50.00 mL g−1; extraction temperature of 84 °C; extraction time of 2 h; and extraction times of 5 times. Triplicate confirmatory experiments under the modified optimal condition for the RSP extraction were carried out, and the average extraction yield was 9.29%, which confirmed the validation of the response model and the suitability of the optimal conditions for the extraction of Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730.

Physicochemical characteristics of RSP

Chemical composition and monosaccharide composition

The proximate compositions of RSP are summarized in Table 2. As shown, the content of the total sugar and protein in RSP was 49.62% and 6.16%, respectively. A sulfate content of 19.58% and a uronic acid content of 11.57% were attributed to the extracted RSP, respectively. The total phenolic content was 2.16%. The monosaccharide compositions of RSP were determined via ion chromatography analysis after hydrolysis using trifluoroacetic acid. RSP contained twelve kinds of monosaccharides in the form of glucose, galactose, xylose, galacturonic acid, mannose, ribose, fructose, mannuronic acid, rhamnose, fucose, arabinose, and guluronic acid, in which the retention time of the first four monosaccharides were 10.96 min, 9.46 min, 12.90 min, and 33.93 min (Fig. S2), respectively. RSP mainly contained glucose, galactose, xylose, and galacturonic acid with mass percentages of 34.08%, 28.70%, 12.46%, and 12.10% (Table 2), respectively.

Structural and morphological characterization

SEM is a considerable powerful tool to monitor the morphological properties of the extracted polysaccharides, for instance, porosity, size, and shape of macromolecules. As shown in Figs. 3a and 3b, RSP is a relatively uniform sheet structure with a rough appearance. The 3D topography, surface roughness, and height of RSP were expounded by AFM (Fig. 3 c, d, and e). Somewhat elongated particles with irregular shape and size pointing towards random coil conformation of RSP were displayed, wherein the vertical distance was 5.86 nm, the horizontal distance was 249 nm, and the variations in height yielded an average of 1.95 nm, with the shortest being 0.04 nm and the tallest 6.46 nm.

Figure 4a shows the FTIR spectrum of RSP between 4000 and 500 cm−1. Both the peaks at 3448 cm−1 and 2926 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibration of O–H and C-H, respectively, indicating the typical absorption peaks of polysaccharides. Both the signals at 1618 cm−1 and 1412 cm−1 were associated with the presence of carbonyl groups, indicating that GPOP-1 contained uronic acid (Cui et al. 2019). The band at 1218 cm−1 was due to the stretching vibration of O = S = O, indicating the presence of sulfate in the sample (Sun et al. 2014). The strong absorption at 1010 cm −1 was dominated by the stretching vibration of the pyranose ring, confirming that the extracted RSP contained pyranose sugar (Wu et al. 2020). Moreover, a medium peak at 930 cm−1 and a weak peak at 866 cm−1 belonged to the beta and alpha configuration. Hence, β-glycosidic bonds were the main type followed by few α-glycosidic bonds in RSP.

Figure 4b shows that the XRD pattern revealed a strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 20.88, manifesting that RSP were semi-crystalline polymers. Consequently, it confirmed that RSP had both crystalline and amorphous portions in their structure.

Antioxidant activities analysis

As shown in Fig. 5a, there was a dose-dependent effect observed between the concentrations of RSP and the DPPH scavenging effect. More specifically, the lowest DPPH scavenging effect (24.34%) was observed at 0.0625 mg mL−1, while a concentration of 2 mg mL−1 yielded the highest clearance rate of 46.74% for DPPH. In the present work, the IC50 values (concentration of the extract capable of scavenging 50% of DPPH) of RSP were 3.00 mg mL−1 (Table S2).

The ABTS radical scavenging abilities of RSP are shown in Fig. 5b. Similar to DPPH radical scavenging activity, the ABTS scavenging ability improved as the RSP concentration increased from 0.0625 to 2.0 mg mL−1. The highest scavenging effect of RSP was 64.42% at a concentration of 2 mg mL−1 in comparison to 94.83% for vitamin C (P < 0.05). The IC50 values of RSP were 1.74 mg mL−1 (Table S2).

Figure 5c depicts the effects of scavenging hydroxyl radicals by RSP. The scavenging effects were in a concentration-dependent way, in which the scavenging rate varies greatly with the concentration in the range of 0.0625 to 0.125 mg mL−1, while the scavenging percentage varies slightly with the concentration in the range of 0.125 to 2.00 mg mL−1. RSP scavenged hydroxyl radical to a greater extent (65.32%) at the highest concentration of 2 mg mL−1, and the lowest activities of hydroxyl radical scavenging were 4.57% at 0.125 mg mL−1. The IC50 value of the RSP was 0.83 mg mL−1 (Table S2).

The ferrous chelating ability of RSP at different concentrations is presented in Fig. 5d. It is obvious that the ferrous ion-chelating activity of RSP kept increasing with dose, with a rate of 43.19% at 2.0 mg mL−1, while EDTA-2Na control showed a ferrous chelating ability of 99.05% at the same concentration (P < 0.05). The IC50 value was 2.76 mg mL−1 for the RSP and 0.01 mg mL−1 for EDTA-2Na (Table S2).

Discussion

Optimization of RSM for RSP extraction

In this study, the hot water extraction technology of RSP was established, and a mathematical model between the factors and the extraction rate of RSP was constructed. The performance of the fitting models was expressed as R2 correlation, and significant analyses were performed using F-test (Chen et al. 2020). The values of R2, R2 adj, and CV demonstrated that the model was remarkably significant, reasonable, reproducible, and reliable (Hu et al. 2020). In addition, the normality assumption was satisfied as to the residual plots approximated along a straight line and the residuals from the least squares fit to show the adequacy of the fitted RSM (Golbargi et al. 2021).

Based on the significance, reliability, and adequacy of the model, we concluded that the model can fully reflect the relationship between the efficiency of hot water extraction of RSP and the four factors including liquid-to solid ratio, extraction temperature, extraction time, and extraction times. With the increase of the liquid-to-solid ratio, extraction temperature, extraction time, and extraction times, the yield of RSP all showed a trend of increasing first and then decreasing. The higher liquid–solid ratio, extraction temperature, extraction time, and extraction times may cause softening of the algal tissue, increasing the solubility of the polysaccharides, which improves the rate of diffusion, thus giving a higher rate of extraction (Hifney et al. 2016). In addition, the density and viscosity of the extract decreased with increasing extraction temperature, time, and times, which was beneficial to extracting buffer into the algal matrix. Nevertheless, the polysaccharide started to decompose when the extraction temperature, time, and times were too high. With the increase of liquid–solid ratio, the increased viscosity of the solvent caused an extension of diffusion distance for the microalgal cells leading to the slow increase of extraction of polysaccharides. Besides, excessive water would weaken the cavitation effect from the extraction process, thus reducing the extraction of polysaccharides. Cho et al. (2019) reported that the polysaccharides yield from Giant African snail using pressurized hot water extraction increased with an increase in the temperature from 100 to 150 °C, while the yield dropped dramatically to 2.53% at 250 °C. The polysaccharides yield from Giant African snail also increased first and then decreased with the increase of solid–liquid ratio (Cho et al. 2019).

At present, there is no multi-factor optimization test for hot water extraction of RSP, and the response surface optimization method is used to achieve an extraction rate of 9.29%. It is worth mentioning here that the RSP yield in this study using the optimum extraction was markedly higher than that previously common hot water extraction with an extraction yield of 3.13% (Fig. S1). This result demonstrates the value of response surface optimization for the further development and improvement of RSP extraction technology. However, hot water extraction method is conventionally used, and it is not compared with any other methodology using modern extraction technology in this study. In the future, we plan to explore various advanced polysaccharide extraction techniques, such as microwave-assisted, ultrasonic-assisted, and enzyme-assisted extraction, promoting the large industrial preparation of RSP (Yuan et al. 2020a).

Physicochemical characteristics of RSP analysis

In general, the chemical structure of polysaccharides determines their physical, chemical, and biochemical properties as well as their biological activities (Maria et al. 2015). The total sugar content of RSP (49.62%) is appropriately consistent with the content that has been reported in Gracilaria chouae sulfated polysaccharides (Khan et al. 2019). Conversely, the carbohydrate content of Nizamuddinia zanardinii was 45.87% by ultrasound-microwave extraction method and 62.04% by cellulase extraction (Alboofetileh et al. 2019b). Research shows that the chemical composition of microalgal polysaccharides depends on algal species, population age, environmental conditions, geographic location, seaweed harvest season, the isolation, and purification methods used (Palanisamy et al. 2017). The protein in RSP existed mostly because they are part of the structure of cell walls and closely associated with polysaccharides (Yaich et al. 2014). The sulfate content of RSP (19.58%) is higher than that previously observed for the extracted polysaccharides from the red alga Porphyra haitanensis, which was almost 17.06% (Wang et al. 2013). Sun et al. (2014) reported that the uronic acids content of extracellular polysaccharides from Microcystic aeruginosa was 10.7% that lower than our reported content. It is known that for polysaccharides from natural products, the existence of sulfate and uronic acid in the molecular structure is responsible for key metabolic activity in living systems. Moreover, higher sulfate and uronic acid content induced higher antioxidant capacity, antiviral, and anticancer properties (Yaich et al. 2014). Wang et al. (2010) reported an increased antioxidant capacity of fucoidan with increasing sulfate and uronic acid content. It was also found that exopolysaccharides (EPS) extracts with a higher sulfate and uronic acid content revealed a strong activity against V. stomatitis virus (Raposo et al. 2014). In addition, Koyanagi et al (2003) demonstrated that persulfate fucoidan has a higher anti-angiogenesis effect, thereby inhibiting the growth of cancer cells more effectively. Other microalgae, like Neochloris oleobundans, Phormidium sp., and Wilmottia murravi, have been reported to possess somewhat similar total phenolic content (Almendinger et al. 2021). The phenolic compounds can act as antioxidants either through single electron or hydrogen atom transfer and thus prevent degenerative diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, osteoporosis, and neurodegeneration. Monosaccharide composition analysis is indispensable for the structural characterization and bioactive studies of polysaccharides and also helpful for the quality control of functional polysaccharides (Liu et al. 2021). The kind of monosaccharide composition in Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 commonly appears in red algae polysaccharides, as described in the review of Cheong et al (2018).

The structural and morphological characterization of RSP not only is related to the function and applications of polysaccharides, but also favorable to understand the phylogeny of the species differences among various algae (Shimonaga et al. 2008). Similar SEM observations of uniform sheet structure with a rough appearance have been reported by Liu et al. for polysaccharides extracted from Sargassum fusiforme (Liu et al. 2020). Research also shows that the smoothness of the microstructure surface of the extracted polysaccharides can safely be related to the feature of sulfated polysaccharides electron micrographs (Khan et al. 2020). From AFM, it can be seen that the size of polysaccharide molecules is much larger than the theoretical value of single chain diameter (0.1–1.0 nm), indicating that the polysaccharide unit could be branched and tangled with each other, which may be due to van der Waals force interaction between polysaccharide molecules and hydrogen bond association between sugar chains (Ji et al. 2021).

In vitro antioxidant activities of RSP analysis

DPPH radical scavenging has been extensively used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activities of bioactive compounds. Previous literature reports have indicated that sulfated polysaccharides derived from Porphyra haitanensis exhibited a DPPH scavenging effect of 34.63% at 2 mg mL−1 (Khan et al. 2020) and 3 mg mL−1 Gracilaria chouae polysaccharide showed 22.3% clearance rate (Khan et al. 2019). The IC50 of polysaccharides from the green alga Ulva lactuca (62.13 mg mL−1) and the benthic diatom Nitzschia longissima (70.83 mg mL−1) were higher than those found in the present investigation (Kokabi et al. 2013; Gopinath and Sampathkumar 2014). The free radical scavenging activity of pineapple core polysaccharides may be mainly caused by the presence of hydroxyl and phosphoric acid in the structure (mainly galacturonic acid) (Hadidi et al. 2020). The polyhydroxy hydrogen donor can scavenge DPPH free radicals, thereby reducing the effect of oxidative stress.

The ABTS scavenging ability improved as the RSP concentration increased, which was in agreement with the electron transfer capability and antioxidant potency of polysaccharides. Khan et al. (2019) found that sulfated polysaccharides of G. chouae possessed an ABTS scavenging ability of 19.07% at 3 mg mL−1. Based on these results, it can be preliminarily concluded that the extracted RSP has potential in acting as ABTS antioxidants.

Hydroxyl radical may be a by-product of immune action, so it has a short life span. These free radicals are highly reactive and can easily cross the cell membrane at specific positions, react with most biological macromolecules, such as carbohydrates, nucleic acids, lipids, and amino acids, resulting in human health damage. Therefore, it is very important to eliminate unnecessary hydroxyl radicals (Song et al. 2018). The polysaccharides of F1, F2, and F3 from L. japonica showed significant scavenging activities on hydroxyl radicals in a concentration-dependent manner, at the concentration of 5 mg mL−1, reaching 35, 60, and 65%, respectively (Song et al. 2018). Xia et al. (2014) reported a polysaccharide extracted from the marine diatom Odontella aurita with a hydroxyl radical scavenging effect of approximately 42% at 2.0 mg mL−1. The RSP had a significant effect on hydroxyl radical scavenging effects in this study might be due to sulfate content and uronic acid content, which is consistent with earlier studies (Chen et al. 2016). The polysaccharide can show good radical scavenging effects in antioxidant tests only when sulfate content and uronic acid content are at a higher level.

Ferrous ions can generate reactive oxygen species by the Fenton free radical reaction, leading to cell oxidative damage (Wang et al. 2020). Henceforth, the chelating influence on ferrous ions has been lately broadly used to assess some antioxidant activity of polysaccharides (Huang et al. 2021). The iron-chelating ability of polysaccharides may be associated with the formation of cross-bridges between the carboxyl group in uronic acid and the divalent ions (Li et al. 2021). The chelating rate of a novel heteropolysaccharide obtained from A. pubescens root was close to our present investigation at 2.0 mg mL−1 (Yuan et al. 2020b). On the whole, RSP was found moderately effective in chelating ferrous irons.

Based on the results of RSP on four different free radical-scavenging experiments, RSP has stronger in vitro antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity of RSP is closely related to the main chain, main chain bond type (such as monosaccharide composition and sugar chain bond type), branched chain structure (such as substitution position and degree of substitution), and high-level configuration. From our study, the reason for the mechanisms in antioxidant activity of RSP cannot be drawn clearly. In the future, we will plan to deeply investigate structure–activity relationships and mechanisms of RSP.

Conclusion

This study is the first to report the extraction of RSP with its physicochemical characterization and antioxidant evaluation. RSM was used to optimize the extraction conditions, which effectively improved the extraction efficiency. The final optimization conditions were detailed as follows: liquid–solid ratio, 50.00 mL g−1; extraction temperature, 84 °C; extraction time, 2 h; and extraction times, 5 times. Under these optimal conditions, the maximum extraction yield was 9.29%. RSP was found to present a rough lamella structure with high sulfate content and uronic acid and mainly comprise glucose, galactose, xylose, and galacturonic acid. In addition, the antioxidant analyses disclosed the RSP exhibited strong hydroxyl radical scavenging ability (IC50 = 0.83 mg mL−1), followed by ABTS radical scavenging ability (IC50 = 1.74 mg mL−1), ferrous chelating ability (IC50 = 2.76 mg mL−1), and DPPH radical scavenging ability (IC50 = 3.00 mg mL−1). The present work provides a theoretical basis for the application of RSP as natural non-toxic antioxidants, potential functional food ingredients, and nutraceutical agents of biomedical. However, investigation on the structure–activity relationships and mechanism of polysaccharides is still required.

Data availability

Individual values of all supporting data are available upon request.

References

Ai S, Fan X, Fan L, Sun Q, Liu Y, Tao X, Dai K (2013) Extraction and chemical characterization of Angelica sinensis polysaccharides and its antioxidant activity. Carbohydr Polym 94:731–736

Alboofetileh M, Rezaei M, Tabarsa M, Ritta M, Donalisio M, Mariatti F, You S, Lembo D, Cravotto G (2019a) Effect of different non-conventional extraction methods on the antibacterial and antiviral activity of fucoidans extracted from Nizamuddinia zanardinii. Int J Biol Macromol 124:131–137

Alboofetileh M, Rezaei M, Tabarsa M, You S (2019b) Ultrasound-assisted extraction of sulfated polysaccharide from Nizamuddinia zanardinii: process optimization, structural characterization, and biological properties. J Food Process Eng 42 (2):e12979.12971-e12979.12913

Alencar PC, Lima GC, Barros F, Costa L, Ribeiro C, Sousa WM, Sombra VG, Abreu C, Abreu ES, Pontes EJFH (2019) A novel antioxidant sulfated polysaccharide from the algae Gracilaria caudata: in vitro and in vivo activities. Food Hydrocoll 90:28–34

Almendinger M, Saalfrank F, Rohn S, Kurth E, Pleissner D (2021) Characterization of selected microalgae and cyanobacteria as sources of compounds with antioxidant capacity. Algal Res 53:102168

Ardiles P, Cerezal-Mezquita P, Salinas-Fuentes F, Rdenes D, Ruiz-Domínguez MC (2020) Biochemical composition and phycoerythrin extraction from red microalgae: a comparative study using green extraction technologies. Processes 8:1628

Awatief F, Hifney KM, Abdel-Gawad, (2016) Industrial optimization of fucoidan extraction from Sargassum sp. and its potential antioxidant and emulsifying activities. Food Hydrocoll 54:77–88

Aziz E, Batool R, Khan MU, Rauf A, Akhtar W, Heydari M, Rehman S, Shahzad T, Malik A, Mosavat SH, Plygun S, Shariati MA (2020) An overview on red algae bioactive compounds and their pharmaceutical applications. J Altern Complem Med 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2019-0203

Bhadja P, Tan CY, Ouyang JM, Kai Y (2016) Repair effect of seaweed polysaccharides with different contents of sulfate group and molecular weights on damaged HK-2 cells. Polymers 8:188

Chen C, Zhao Z, Ma S, Rasool MA, Wang L, Zhang J (2020) Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction, refinement and characterization of water-soluble polysaccharide from Dictyosphaerium sp. and evaluation of antioxidant activity in vitro. J Food Meas Charact 14:963–977

Chen Y, Liu X, Xiao Z, Huang Y, Liu B (2016) Antioxidant activities of polysaccharides obtained from Chlorella pyrenoidosa via different ethanol concentrations. Int J Biol Macromol 91:505–509

Cheong KL, Qiu HM, Hong D, Yang L, Khan B (2018) Oligosaccharides derived from red seaweed: production, properties, and potential health and cosmetic applications. Molecules 23:2451

Cho YJ, Getachew AT, Saravana PS, Chun BS (2019) Optimization and characterization of polysaccharides extraction from Giant African snail (Achatina fulica) using pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE). Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 18: 100179

Cui M, Wu J, Wang S, Shu H, Zhang M, Liu K (2019) Characterization and anti-inflammatory effects of sulfated polysaccharide from the red seaweed Gelidium pacificum Okamura. Int J Biol Macromol 129:377–385

Dai L, Tao L, Jin X, Wu H, Wu H, Li T, Xiang W (2020) Evaluating the potential of carbohydrate-rich microalga Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730 as a feedstock for biofuel and β-glucans using strategies of phosphate optimization and low-cost harvest. J Appl Phycol 32:3051–3061

Dong H, Lin S, Zhang Q, Chen H, Lan W, Li H, He J, Qin W (2016) Effect of extraction methods on the properties and antioxidant activities of Chuanminshen violaceum polysaccharides. Int J Biol Macromol 93:179–185

Fleita D, El-Sayed M, Rifaat D (2015) Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of enzymatically-hydrolyzed sulfated polysaccharides extracted from red algae Pterocladia capillacea. LWT-Food Sci Technol 63:1236–1244

Foo SC, Yusoff FM, Ismail M, Basri M, Yau SK, Khong N, Chan KW, Ebrahimi M (2017) Antioxidant capacities of fucoxanthin-producing algae as influenced by their carotenoid and phenolic contents. J Biotechnol 241:175–183

Gaignard C, Gargouch N, Dubessay P, Delattre C, Michaud P (2019) New horizons in culture and valorization of red microalgae. Biotechnol Adv 37:193–222

Golbargi F, Gharibzahedi S, Zoghi A, Mohammadi M, Hashemifesharaki R (2021) Microwave-assisted extraction of arabinan-rich pectic polysaccharides from melon peels: optimization, purification, bioactivity, and techno-functionality. Carbohydr Polym 256 (1):117522

Gopinath M, Sampathkumar P (2014) Antioxidant activity from ethanolic extract of diatom Nitzschia longissima. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 3:1139–1149

Guidara M, Yaich H, Amor IB, Fakhfakh J (2021) Effect of extraction procedures on the chemical structure, antitumor and anticoagulant properties of ulvan from Ulva lactuca of Tunisia coast. Carbohydr Polym 253: 117283

Hadidi M, Amoli PI, Jelyani AZ, Hasiri Z, Rouhafza A, Ibarz A (2020) Polysaccharides from pineapple core as a canning by-product: extraction optimization, chemical structure, antioxidant and functional properties. Int J Biol Macromol 163:2357–2364

Hans N, Malik A, Naik S (2020). Antiviral activity of sulfated polysaccharides from marine algae and its application in combating COVID-19: mini review. Bioresour Technol Rep 100623

Hao W, Wang SF, Zhao J, Li SP (2020) Effects of extraction methods on immunology activity and chemical profiles of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides. J Pharmaceut Biomed 185:113219

Hifney AEF, Fawzy MA, Abdel-Gawad KM, Gomaa M (2016) Industrial optimization of fucoidan extraction from Sargassum sp. and its potential antioxidant and emulsifying activities. Food Hydrocoll 54:77–88

Hu Z, Zhou H, Zhao J, Sun J, Li M, Sun X (2020) Microwave-assisted extraction, characterization and immunomodulatory activity on RAW 264.7 cells of polysaccharides from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds. Int J Biol Macromol 164:2861–2872

Huang Q, He W, Khudoyberdiev I, Ye C-L (2021) Characterization of polysaccharides from Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg Roots and their effects on antioxidant activity and H2O2-induced oxidative damage in RAW 264.7 cells. BMC Chem 15:9

Hui S, Lu J, Zhou W (2019) Structure characterization and antioxidant activity of fucoidan isolated from Undaria pinnatifida grown in New Zealand. Carbohydr Polym 212:178–185

Ji C, Zhang Z, Zhang B, Chen J, Guo S (2021) Purification, characterization, and in vitro antitumor activity of a novel glucan from the purple sweet potato Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. Carbohydr Polym 257 (8):117605

Khan BM, Qiu HM, Wang XF, Liu ZY, Cheong KL (2019) Physicochemical characterization of Gracilaria chouae sulfated polysaccharides and their antioxidant potential. Int J Biol Macromol 134:255–261

Khan BM, Qiu HM, Xu SY, Liu Y, Cheong KL (2020) Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant activity of sulphated polysaccharides derived from Porphyra haitanensis. Int J Biol Macromol 145:1155–1161

Kokabi M, Yousefzadi M, Ali Ahmadi A, Feghi MA, Keshavarz M (2013) Antioxidant activity of extracts of selected algae from the Persian Gulf. Journal of the Persian Gulf (Mar Sci) 4:45–50

Koyanagi S, Tanigawa N, Nakagawa H, Soeda S, Shimeno H (2003) Oversulfation of fucoidan enhances its anti-angiogenic and antitumor activities. Biochem Pharmacol 65:173–179

Li CY, Liu L, Zhao YW, Chen JY (2021) Inhibition of calcium oxalate formation and antioxidant activity of carboxymethylated Poria cocos polysaccharides. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:1–19

Li T, Xu J, Wu H, Jiang P, Chen Z, Xiang W (2019a) Growth and biochemical composition of Porphyridium purpureum SCS-02 under different nitrogen concentrations. Mar Drugs 17:124

Li T, Yang F, Xu J, Wu H, Xiang W (2020) Evaluating differences in growth, photosynthetic efficiency, and transcriptome of Asterarcys sp. SCS-1881 under autotrophic, mixotrophic, and heterotrophic culturing conditions. Algal Res 45:101753

Liu D, Tang W, Yin JY, Nie SP, Xie MY (2021) Monosaccharide composition analysis of polysaccharides from natural sources: hydrolysis condition and detection method development. Food Hydrocoll 116 (3):106641

Liu J, Wu SY, Chen L, Li QJ, Shen YZ, Tong HB (2020) Different extraction methods bring about distinct physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of Sargassum fusiforme fucoidans. Int J Biol Macromol 155:1385–1392

Liu Y, Qiang M, Sun Z, Du Y (2015) Optimization of ultrasonic extraction of polysaccharides from Hovenia dulcis peduncles and their antioxidant potential. Int J Biol Macromol 80:350–357

Li Y, Yun D, Li Lu, Yang, (2019b) Hot water extraction and artificial simulated gastrointestinal digestion of wheat germ polysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol 123:174–181

Maria D, Alcina DM, Rui D (2015) Marine polysaccharides from algae with potential biomedical applications. Mar Drugs 13:2967–3028

Palanisamy S, Vinosha M, Marudhupandi T, Rajasekar P, Prabhu NM (2017) Isolation of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum brown algae: Structural characterization, in vitro antioxidant and anticancer activity. Int J Biol Macromol 102:405–412

Pereira L, Critchley AT (2020) The COVID 19 novel coronavirus pandemic 2020: seaweeds to the rescue? Why does substantial, supporting research about the antiviral properties of seaweed polysaccharides seem to go unrecognized by the pharmaceutical community in these desperate times? J Appl Phycol 32:1875–1877

Raposo M, Maria FDJ, Morais De, Bernardo de Morais AMM (2013) Bioactivity and applications of sulphated polysaccharides from marine microalgae. Mar Drugs 11:233–252

Raposo M, Morais AD, Morais RD (2014) Influence of sulphate on the composition and antibacterial and antiviral properties of the exopolysaccharide from Porphyridium cruentum. Life Sci 101:56–63

Shang XC, Chu D, Zhang JX, Zheng YF, Li YJ (2021) Microwave-assisted extraction, partial purification and biological activity in vitro of polysaccharides from bladder-wrack (Fucus vesiculosus) by using deep eutectic solvents. Sep Purif Technol 259:118169

Shimonaga T, Konishi M, Oyama Y, Fujiwara S, Satoh A, Fujita N, Tsuzuki M (2008) Variation in storage α-glucans of the Porphyridiales (Rhodophyta). Plant Cell Physiol 49:103–116

Song H, He M, Gu C, Wei D, Liang Y, Yan J, Wang C (2018) Extraction optimization, purification, antioxidant activity, and preliminary structural characterization of crude polysaccharide from an Arctic Chlorella sp. Polymers 10:292

Sun L, Wang C, Lei S (2008) Effects of light regime on extracellular polysaccharide production by Porphyridium cruentum cultured in flat plate photobioreactors. Bioinformat Biomed Eng 5:1488–1491

Sun Y, Wang H, Guo G, Pu Y, Yan B (2014) The isolation and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from the marine microalgae Isochrysis galbana. Carbohydr Polym 113:22–31

Venkatesan M, Arumugam V, Pugalendi R, Ramachandran K, Sengodan K, Vijayan SR, Sundaresan U, Ramachandran S, Pugazhendhi A (2019) Antioxidant, anticoagulant and mosquitocidal properties of water soluble polysaccharides (WSPs) from Indian seaweeds. Process Biochem 84:196–204

Wang B, Niu J, Mai B, Shi F, Liu Q (2020) Effects of extraction methods on antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides from superfine powder Gynostemma pentaphyllum Makino. Glycoconjugate J 37:777–789

Wang J, Jin W, Hou Y, Niu X, Zhang H, Zhang Q (2013) Chemical composition and moisture-absorption/retention ability of polysaccharides extracted from five algae. Int J Biol Macromol 57:26–29

Wang J, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Song H, Li P (2010) Potential antioxidant and anticoagulant capacity of low molecular weight fucoidan fractions extracted from Laminaria japonica. Int J Biol Macromol 46:6–12

Wu YT, Huo YF, Xu L (2020) Purification, characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Porphyra haitanensis. Int J Biol Macromol 165:2116–2125

Xia S, Gao B, Li A, Xiong J, Ao Z, Zhang C (2014) Preliminary characterization, antioxidant properties and production of chrysolaminarin from marine diatom Odontella aurita. Mar Drugs 12:4883–4897

Yaich H, Garna H, Besbes S, Barthelemy JP, Paquot M, Blecker C, Attia H (2014) Impact of extraction procedures on the chemical, rheological and textural properties of ulvan from Ulva lactuca of Tunisia coast. Food Hydrocoll 40:53–63

Yu F, Li H, Meng Y, Yang D (2013) Extraction optimization of Angelica sinensis polysaccharides and its antioxidant activity in vivo. Carbohydr Polym 94:114–119

Yuan Q, Li H, Wei Z, Lv K, Gao C, Liu Y, Zhao L (2020a) Isolation, structures and biological activities of polysaccharides from Chlorella: a review. Int J Biol Macromol 163:2199–2209

Yuan Q, Zhang J, Xiao C, Harqin C, Zhao L (2020b) Structural characterization of a low-molecular-weight polysaccharide from Angelica pubescens Maxim. f. biserrata Shan et Yuan root and evaluation of its antioxidant activity. Carbohydr Polym 236: 116047

Yuan Y, Macquarrie D (2015) Microwave assisted extraction of sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidan) from Ascophyllum nodosum and its antioxidant activity. Carbohydr Polym 129:101–107

Zhang J, Liu L, Ren Y, Chen F (2019) Characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by microalgae with antitumor activity on human colon cancer cells. Int J Biol Macromol 128:761–767

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciatively acknowledge financial support from the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B1111030004) ; Key Special Project for Introduced Talents Team of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) (GML2019ZD0406); and Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province of China (2019B030316027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Na Wang designed and performed the experiment, analyzed the experimental data, and drafted the manuscript. Lumei Dai participated in the cultivation of Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730. Zishuo Chen helped to draft the manuscript and revised this manuscript. Tao Li, Jiayi Wu and Houbo Wu gave certain experimental supports in the extraction of polysaccharides. Hualian Wu helped to analyze the experimental data, draft the manuscript, and revise this manuscript. Wenzhou Xiang took part in designing the study, coordinating the study, and assisted with revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, N., Dai, L., Chen, Z. et al. Extraction optimization, physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Rhodosorus sp. SCSIO-45730. J Appl Phycol 34, 285–299 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-021-02646-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-021-02646-2