Abstract

The purpose of this article is to present the design and main findings of a three-year study analyzing the transition from printed to digital educational materials for primary education in Spain. Special attention has been given to the metamorphosis of didactic materials in the context of the digital society. The research focused on two issues: (a) the opinion of educational agents regarding digital educational material, and (b) the use made of digital educational materials in schools and classrooms. Two different but complementary studies were designed and carried out. The first explored the perspectives or subjectivities of educational agents—teachers, material creators and families. The second was a multi-case study involving several schools and analyzing the educational use of materials by teachers. Our findings indicate that the dissemination of digital educational materials is carried out through both paid commercial platforms and public access platforms promoted by educational administrations and that an expository teaching model underlies most online teaching materials. Educational agents have high expectations and a positive predisposition towards digital resources. Likewise, it has been found that teachers make functional and hybrid didactic adaptations of digital resources. Finally, it is suggested that the study’s approach and methodology have potential for extrapolation to other national contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This article derives from an empirical research carried out over three years (2016–2019) whose purpose was to explore and analyses the digital educational resources offered online for Primary Education in Spain. Our research design is based on the assumption that the omnipresence of digital technologies in their multiple formats (tablets, smartphones, multimedia, laptops, etc.) is not only transforming the productive, economic and service sectors of our society, but has also altered the forms and processes of elaboration, distribution and consumption of culture and knowledge. The latter is directly affecting the traditional cultural industries of packaging and dissemination of information (music, cinema, media, etc.), generating a crisis of the traditional model of production and access to these cultural products (in the field of music, cinema, advertising, press, books, etc.). Similarly, these phenomena of digital transformation are also occurring with traditional educational materials such as textbooks, where the didactic monopoly that the textbook had years ago in the classroom is being questioned, having to share it with other resources of a digital nature. In this article we set out to explore what visions and opinions do educational agents (teachers, families and publishers) have about the potential of digital educational resources, and what are the didactic practices of these resources in the school classrooms.

2 Theoretical Background

The academic production developed on didactic resources or materials for three decades has generated a wide and abundant bibliography that has addressed the conceptualization of teaching aids, didactic materials or educational resources. This set of works have shown that:

-

Didactic or instructional means are an object made up of both an artifactual-technological dimension and a semantic-symbolic dimension intended to facilitate some type of teaching-learning process.

-

Didactic media play different didactic and curricular functions in the professional practice of teaching (preparation or planning of classes, support for teaching situations during their development, tools for evaluation).

-

Didactic media are resources that stimulate and foster empirical and/or symbolic learning experiences for students to acquire knowledge.

The didactic material or resource can be defined as a cultural, physical or digital object, elaborated to generate learning in a certain educational situation (Area, 2020). For this reason, the experience of use or interaction of the student with the didactic material or artifact occurs in a school context that is conditioned by multiple variables: teaching methodology, availability of resources in the center and classroom, activities developed, among others.

For more than a decade, digital technologies have been driving a profound transformation in the production, distribution and consumption of culture and knowledge (Einav, 2015; Engen, 2019; Rossignoli et al., 2018). This process is a complex phenomenon involving diverse intertwining dimensions that go far beyond the mere change of technological format. Digital transformation is directly affecting the field of educational material and school teaching resources (Author, 20xx; Al-lmamy, Samer, 2020; Gopal, 2020) and this is exemplified by the conversion of traditional printed materials, such as textbooks, into a new generation of digital educational resources (Xie et al., 2018). Around school teaching materials, and in particular textbooks, there is an important cultural industry. For more than a decade there has been the concept of Open Educational Resource (OER) (Wiley, 2008; Lane y MacAndrew, 2010; Wiley, Bliss and McEwen, 2014) that is promoting the use of digital resources in the classroom.

2.1 What are the Digital Educational Resources (DER)?

Educational resources are currently one of the visible axes of the school's digital transformation process. Paper textbooks are beginning to be replaced by different digital resources that allow students to develop learning activities of a different nature: search for and critically analyze information on the Internet, develop collaborative projects between groups of students, create digital content in formats audiovisual and multimedia, etc.

Around them there is an important cultural industry for the production and marketing of digital educational resources. Likewise, government educational policies are also being developed that facilitate the creation and use by teachers of digital resources in schools. A large body of literature has identified a number of technical features or attributes that define them (Reints, and Wilkens, 2014): they are reusable, accessible, interoperable, portable and durable. They are also differentiated by their granularity, which refers to the size and complexity or scope of the object, which can range from a simple activity or specific exercise to the design of an entire course. Learning objects would be like Lego or puzzle pieces that can be inserted, interchanged and intermixed.

There are different classifications of these types of artefacts or digital objects for educational purposes. By way of examples, we will present the one made by Churchill (2017) where the form of representation of the content offered by the material interacts with the type of knowledge that we want to promote in the students. In this way, this author classifies digital resources and materials with educational potential as follows: (a) information visualisation resources or objects (maps, timeline, graphics, icons, photographs…); (b) knowledge exposition resources (tutorial ebook, multimedia presentation slides, video recording, audio podcast, tutorial…); (c) resources for practice or exercise (interactive games, video games, online test,..); (d) resources for the presentation of concepts (adopting the format of courses or lessons); and (e) resources for the presentation of data (interactive environment for data manipulation).

Among the different types of digital educational resources we can highlight the following concepts (Area, 2020):

-

Digital object It is a digital file that carries any type of content, information and/or knowledge. They adopt different formats or languages of expression (documents, videos, photos, infographics, podcasts, augmented reality, geolocation, …). When stored in an organised way, they constitute a repository of digital objects.

-

Digital learning object It is a particular type of digital objects created with a didactic intention. Wiley (2000) defines them as "any resource that can support the learning process mediated by some technology", which offers a very broad characterisation of them. In most cases, they take the form of activities or exercises to be completed by a student; a video to be watched, a reading text, an explanatory animation or any other digital resource created for educational purposes. They are abundant in educational cyberspace. They are largely multimedia and interactive in nature. They are also often organised and accessible in educational online libraries or repositories.

-

Digital textbook Electronic or digital textbooks are a particular type of highly relevant digital learning materials. They are composed of multiple digital learning objects assembled as a single learning artefact, as a virtual environment. They represent the digital evolution or transformation of paper textbooks: they are a structured package of a complete teaching proposal (with contents and activities) planned for a specific subject and a specific course or educational level. Like traditional textbooks, they are industrially produced and are used by teachers to manage their teaching in a systematic, methodical and regular way. Unlike paper textbooks, digital textbooks allow a certain degree of flexibility, malleability and adaptability to the characteristics of the teacher and his or her class group. The current format of these digital school books, in the Spanish context, is distributed through online platforms.

-

Educational online portal or platform This refers to those websites that host, in a more or less structured way, a set of teaching materials and resources that have the potential to be used in teaching–learning processes. These portals or platforms are differentiated according to whether they are free or restricted access (requiring a user ID and password to access the material). A distinction can also be made between portals created and managed by institutional bodies (such as those of regional and state educational administrations) or by private companies (such as publishers' portals). In the first case, they are platforms or portals that offer free and open access digital resources or objects (Butcher, 2015; OECD, 2007). In the second case, they are often portals that require payment of an access licence.

3 Research Topics on Digital Educational Resources (DER)

There is a large body of literature on research on digital educational resources at the international level. The works by Fernandes et al. (2020), Branch et al. (2019) provide good insight into this field. The lines that have received the most attention involve the consideration of educational digital resources as “objects or artifacts” for teaching and learning (Wiley, 2008). In this respect, the analysis and evaluation of these resources may be the line of research that has received the most attention (Kohout-Tailor & Sheaffer, 2020).

The concept of open digital resources (Wiley et al., 2014) has also been the focus of much research, especially insofar as storage and distribution through open online repositories (Kim et al., 2019; Marcus-Quinn & Diggins, 2013). Author (20xx) identified a variety of lines and topics currently under development regarding educational resources and materials which are summarized in Table 1.

One of the most relevant studies on digital resources for the school environment (Fuhs and Bock, 2018) clearly demonstrates that educational quality does not depend solely on the characteristics of the technology or educational material being used, but rather on the corresponding context, teacher professionalism and teaching method. It has been found that the continued use of digital textbooks generates different emotions in teachers (Chiu, 2017).

A shared assumption in this field is the urgent need for schools to appropriate digital technology and radically transform their discourse and pedagogical practice (Avvisati et al., 2013; Bottino, 2020; Nedungadi et al., 2018). However, we should emphasize that it is well known that the mere substitution of one type of technology for another does not transform teaching or learning processes. Many more variables (organizational, educational, personal, cultural) intervene in processes of pedagogical change and innovation (Grönlund et al., 2018). In order to transform educational methods and practices with materials, it is necessary to develop new pedagogical and curricular approaches, rearrange school organization, build teacher professionalism, and create new resources, materials, contents, tools and services so that teachers, students and their families can teach and learn online.

In summary, we can say that the principles or reference points on which this research is based are as follows:a) A systemic view on research in educational technologies where we not only focus attention on the characteristics of the media or materials as digital objects, but also analyse them contextually and functionally in relation to the rest of the agents, dimensions and educational processes of the school system;b) The theory on the processes of innovation and educational change in schools, since digital media and materials are a necessary curricular component whose role or functionality, among others, is to facilitate the putting into practice and implementation of innovative educational proposals and projects linked to the transformation of the school in the digital society of the twenty-first century;c) A holistic and critical approach to research on educational technologies that explores their impact on educational change through the thinking of educational agents and their classroom practices.

4 Research Design and Procedure

This research aimed to explore and analyze the phenomena and processes that surround and accompany the process of new models of production and distribution of teaching materials on digital platforms, as well as the impact they have on the teaching and learning practices developed in schools and classrooms. To this end, we focus our attention on the analysis of the supply of digital teaching materials in Primary Education, carrying out the study in three autonomous communities or regions of Spain: the Canary Islands, Galicia and the Valencian Community.

The starting questions for the development of this research were the following:

-

What kind of digital educational materials are currently offered online for the school use?

-

What pedagogical model underlies them?

-

What representation do the different educational and social agents involved have?

-

How are they used and what impact do they have on teaching and learning for the diversity of students in our classrooms?

-

What recommendations can be made to the different agents and sectors involved in order to produce and use the school resources and content distributed online with educational quality?

We use a mixed methodological approach with diverse research techniques: content analysis, interviews, classroom observations, discussion groups, documentary analysis, multi-case analysis, … and where we have explored the visions and representations of the different educational agents and actors: teachers, students, families, publishers and technical managers of the educational administrations. The basic questions that guided the research were the following:

-

What do educational agents think about digital educational material?

-

What use is made of digital educational materials in schools and classrooms?

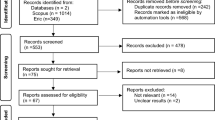

We carried out two studies analyzing these educational materials from a multidimensional perspective. Our qualitative research methodology involved a combination of analysis strategies. Figure 1 displays our two-level approach: the analysis of educational agents’ subjective representations, and the analysis of practices with digital educational resources in schools. Each study had its own specific objetives and procedures (Table 2).

4.1 Study I. The Analysis of the Subjectivities of Educational Agents (teachers, families and editors)

The aim of Study I was to identify the representations and opinions regarding the transition from textbooks to digital educational content of the various agents involved: teachers, families and managers of institutional portals as well as private publishing companies (Appendix 1). The first step was elaborating interview guidelines for each of the four agent groups, which were validated by professionals. The following phase was selecting a sample for each group. In the case of teachers and families, the criteria for selection were that teachers taught the 5th or 6th grade and families with children in those grades, and that teachers and students were using DER (Digital Educational Resources). However, the selection was incidental as it was a quick way of attaining the sample. With respect to teachers, the discussion group technique was used to determine attitudes, feelings, motivations, perceptions and opinions from the perspective of those involved. It was also an opportunity to provide professional support while promoting the exchange of ideas and experiences. With families and students, the interview technique was used.

A total of 41 teachers were interviewed in six discussion groups. They were structured interviews. Six to ten people participated in each session, which lasted 45 to 60 min. Six group interviews with families lasted 15 to 20 min, involving a total of 31 families and 20 students. The sessions were conducted by members of each research team at the school or corresponding university, and were recorded in audio or audiovisual format, depending on participant permission. The questions asked to each type of educational agent can be seen in appendix 4.

The opinions of platform managers were gathered through individual interviews. Ten managers from publishing companies were interviewed, as were 3 managers from institutional platforms. Sessions were conducted by members of each research team by videoconference, except for two session which were carried out in the interviewee’s work environment. Finally, a summary report was drafted by a group of researchers from each team.

The process of analysing the interviews was as follows: First level of analysis (level 1): Elaboration of Question Matrices synthesising the answers of each subject/group to each question asked. Second level (level 2): From the previous table, another Table or Matrix of categories that represent or synthesise what is expressed by each agent according to the identified categories is elaborated. Third level (level 3): Comparative matrices between agents. This matrix is constructed as a synthesis of all of the above. It consisted of creating a single double-entry table in which each type of agent (Teachers, Students, Families and Publishers) appears vertically, and the different categories of the interviews vertically. Level 4: Comparative matrix of educational agents at the Spanish national level (See appendix 5).

The categories used for coding data varied according to agent but followed a similar design. For teachers, the main categories were as follows: value for learning of DER (Digital Educational Resources), DER use in classroom, training in DER use, school context, economic barriers to DER use. For families, the categories were as follows: DER value for learning, economic barriers to DER use, DER use at home and for communication with teachers. For students the categories were as follows: educational resource preference (DER or printed text books), personal use of digital devices, academic use of digital devices. The categories for institutional portal managers and publishing house platform managers were similar: identification data, portal structure, DER production or development, DER evaluation, educational model supported by the portal, and final comments (on the role of public institutions and private enterprises in DER production, the future of DER and printed textbooks, and the training of teachers and families in DER use).

4.2 Study II. The Analysis of School use of Digital Materials

This was a multi-case study undertaken to explore the use of educational materials, and was surely the most complex in terms of methodology. Studying a set of cases can help to identify common characteristics of a phenomenon that appear in different contexts, and this approach is very useful for understanding vague or unexplored concepts to facilitate generalization (Yin, 2009). Seven case studies were undertaken. The selection criteria were the following: (a) Primary schools (b) with experience in the use of digital content (c) 5th and 6th grades (d) located in three different regions of Spain. The first step was initial contact with schools to present the case study process and conditions for schools. The second phase involved selecting schools, negotiating study conditions, and planning the data collection process. The next step was data collection at each school through direct non-participant classroom observations, interviews and document analysis.

Eighteen groups from 7 schools were observed (two classrooms in four schools, one classroom in one school, three classrooms in one school and six classrooms in another school). All groups included 5th and 6th graders, except for one school where 4th and 5th graders were observed. Class size ranged from 22 to 26 students. All classes were conducted by one teacher, except two groups at one school that were mixed for certain subjects (4th and 5th grades) and conducted by two teachers. Approximately 4 sessions were observed in every classroom for a total of 85 sessions.

The next phase consisted of data analysis and reports for each case following a common format with the following sections: case features; agents views on ICT at school and DER; classroom practices with ICT and DER; and conclusions. Reports were then submitted to schools for comments. The final phase involved drafting the multi-case study to compare the main findings of the 7 case studies.

A variety of analytical tools and techniques were applied in Study II. The data collection procedures can be found in Appendix 2.The following tools for information collection were used: interview guidelines for use with school principals, ICT coordinators, teachers (in charge of overserved classrooms), teacher team coordinators, and parent association representatives; a class observation sheet; and a document analysis sheet. Interview data were transcribed and coded, then themes and findings were identified for each category. Class observation sheet data was summarized and organized around the following topics: features of the observed groups; teaching–learning processes with ICT, use of ICT and DER, and conclusions including strengths, weaknesses, facilitating factors for ICT and DER use, and areas for improvement. The dimensions and sub-dimensions of analysis used can be found in Appendix 3.

To prepare for multi-case analysis, the original 7 case study reports were rewritten according to the following outline: the stage (setting the action), classroom practices (unraveling the action), and conclusions. The first part of the report involved school background information for understanding the case, the second part identified instructional uses of DER observed in classrooms and areas for improvement. Then the multi-case study was undertaken comparing similarities and differences in the seven schools and identifying six different uses of DER, ranging from an integrated use of ICT at school and in the community to use of ICT and DER in association with textbook activities (printed or digitalized).

5 Results

Our results are structured in accordance to the studies conducted in the project.

5.1 Study I. What do Educational Agents Think About Digital Educational Resources?

The purpose of the first study was to identify and analyze the views of the agents involved (families, teachers, publishers and institutional platforms) regarding design, dissemination and use of digital educational materials. In order to do so, we designed a study with two specific aims: a) to identify the views of educational agents (teachers and families) insofar as the didactic potential of digital content in primary education and b) to analyze the representations of institutional website/repository managers and commercial educational content producers regarding the didactic potential of digital content in primary education.

With respect to their views on the creation and use of the educational materials, teachers emphasized the need for reciprocity in the teaching–learning process. Teachers said that digital materials do not replace traditional materials, but instead complement them. They believe that it is necessary to improve academic ICT training for teachers at the university level (Bachelor's and Master's degrees).

Insofar as the views of institutional portal technical managers, it is evident that teams charged with designing and creating classroom resources for teachers and students are made up of diverse profiles, but educational professionals predominate. The institutional portals base their activity on collaboration with active teachers who contribute knowledge in educational technology, teaching and pedagogical experience as well as mastery of a specific subject or curricular area.

With respect to development and evaluation, it should be noted that many institutional portals function as free access websites where teachers can publish their own resources, elaborated according to a diversity of criteria. On the other hand, websites that work with teachers and multidisciplinary teams in the elaboration of digital educational materials often have similar elaboration criteria.

As regards the views of publishing company technical managers, all the interviewees responded that teachers at all educational levels (university, secondary, primary and early childhood) participated in the creation of DER. They are usually active in their schools and have the support of experts in education and other fields. The work teams that create DER are multidisciplinary. It is noteworthy that publishers are beginning to take criteria other than aesthetics into account, such as the following: materials must not transmit gender-related stereotypes (e.g. social roles, behavior patterns, personal image, and social expectations), they must not be biased and they must not discriminate based on social class, sex, culture or beliefs. Furthermore, criteria must be adapted to objectives, content and methodological approach. They must be contextualized within the proposed didactic unit and psychological impact must be suitable for student age.

Most of the families participating in the discussion groups had an open attitude towards the use of DER in the classroom, opting for combination with print and analog media. Not all families considered DER necessary for every subject; however, they do mention the importance of using ICT in the classroom to facilitate the teaching–learning process and to expose students to the world of information and communication. It is noteworthy that some family representatives recognized the effort and competence of teachers when it comes to implementing technology in a pedagogical, ethical and effective way. In addition, digital resources were considered to be a fundamental tool for addressing inequality at school.

Table 3 shows the similarities and differences in agents’ views. Regarding the degree of technology integration into teaching–learning processes, all educational agents agreed on the need to promote a hybrid model combining analog and digital materials. Likewise, they insisted on the need for responsibility, criticism and awareness when digitizing curricular content, since it is not merely a matter of supplanting traditional analogue materials with digital ones, but rather connecting them to achieve greater scope, motivation and attention.

5.2 Study II. Use of Digital Educational Materials in Schools and Classrooms. A Multi-case School Study

The second study involved the analysis of how digital educational resources are used in seven schools. The dimensions and sub-dimensions of the analysis are shown in Table 4.

The main findings are summarized below

-

The role of textbooks in classroom practice. The cases studied reflect a diversity of textbook practices. In one case, teachers did not use textbooks, and in another four cases, textbooks seemed to be losing their prominence in teaching practice. Although textbooks continued to function as a guide, in most cases their role was complementary to other materials, including DER.

-

The origin of DER. Four main sources were identified: open access materials from the web, commercial platforms, educational administration portals and materials created by teachers themselves. In every school, there were teachers who prepared DER, however, the most frequent sources were the web (open access materials) and educational administration portals. The latter was the most common source in state schools, while commercial textbook publishers were not the primary source in any case.

-

The creation of digital materials by teachers. Most teachers used or adapted existing materials. However, some teachers created their own DER, and combined them with other DER from various sources as well as non-digital materials. In fact, most of the teachers interviewed considered that the most appropriate way to proceed was to combine DER with other types of material. Nevertheless, the quality of materials created by teachers was usually poorer than the materials available from other sources. The main reason given by teachers for developing DER was that available materials were not tailored to the specific needs of their students. From the teachers’ standpoint, DER are used for various purposes: to present activities to students, to receive students' learning products (reproductive or creative) and to evaluate students. They are also used to motivate students and promote different types of learning. From the students' standpoint, DER are used to develop learning products (reproductive or creative), to learn, and to communicate what they have learned to their peers and teachers.

-

The impact of these materials on classroom activities. The observations made in the different groups suggest that what determines the type of activities undertaken in the classrooms is not the nature of the material itself, but the underlying teaching methodology. This finding has already been confirmed by previous studies. There were teachers who used digital materials in the context of traditional teaching methodologies. However, it is worth bearing in mind that DER have pedagogical potential that textbooks do not, but this potential can only be realized in the context of effectively innovative methodologies.

In summary, the multi-case study in seven schools showed that the pedagogical integration of ICT and the use of digital educational materials do not depend solely on the action of single teachers in the classroom, but on school decisions taken over time regarding educational technologies (Author, 20xx).

6 Discussion and Conclusions

Insofar as the opinion of educational agents, teachers expressed the need to have more and better training on the creation, use and evaluation of digital educational materials, as has been highlighted in previous research (Magdas & Dringu, 2016; Mahapatra, 2020; Palacios et al., 2020). Managers of institutional portals drew attention to assessment by teachers and pupils as a way to understand the socio-educational impact of their platforms. Technicians from commercial publishing companies expressed the importance of focusing on the needs and criticisms from teachers and pupils. (Allen Knight, 20xx) as well as coordinating technical teams to create teaching materials with high interactive and pedagogical value. In line with Marsh et al. (2017), it was considered that families should participate more actively in the design of digital educational resources.

A common aspect mentioned by the different members of the educational community was the need to develop hybrid models supporting the coexistence of analog and digital material. Studies such as Weng et al. (2018) also report this opinion.

Another consideration emerges as a consequence. In the process of DER production, it would be very beneficial to incorporate methods of co-creation in order to take advantage of users’ diverse perspectives and capabilities (whether teachers, pupils or families). Users should be involved in the processes not only of design but also of evaluation, because the production of DER should not be left solely in the hands of publishing companies, educational experts, nor educational researchers.

Teachers tend to use or adapt existing materials. They functionally modify resources produced by other entities (companies, educational administrations, and other teaching groups) to their didactic needs and the characteristics of their pupils. Some teachers create their own digital educational materials and use them in combination with other digital and analog resources. Usually, the technical and pedagogical quality of self-produced materials is often poorer than those available from other sources. The main reason teachers give for self-producing materials is that the commercial and institutional materials available do not meet the specific needs of their pupils. The didactic functionality of self-produced digital materials is to motivate pupils and promote different types of learning (Zwart et al., 2017).

Another conclusion of this study, which is in line with previous research, is that the type of activities carried out in classrooms is not determined by characteristics of materials themselves, but by the underlying teaching methodology. Likewise, there are certain barriers (e.g. school institutional rigidity and isolation, teachers’ professional practices and beliefs) which affect the use of educational resources (Sumardi et al., 2020; Sunkel, 2012).

These findings lead to a third conclusion. Rather than focusing on the provision of technological resources to individual schools, educational policies regarding ICT and DER should provide teachers with training opportunities to foster innovations with educational resources and technologies, as well as promoting school collaboration projects and improvement networks (Author, 20xx).

Our study findings have practical implications for improving the technical and pedagogical quality of digital didactic resources. These recommendations have already been disseminated (Author, 20xx). This guide provides practical guidance for enterprises and educational institutions on the design, development and evaluation of digital learning materials, recommendations for teachers on the selection and use of materials in the classroom, and guidance for families on the educational use of digital technologies at home.

Furthermore, the design of this research project, which approaches educational resources from a multidimensional perspective (didactic objects; agent subjectivities; school and classroom practices), has the potential for replication and adaptation to other regional and national contexts. This methodology makes it possible to understand the characteristics of materials, their online distribution platforms, how they are viewed by educational agents, and their classroom use in different school contexts.

It should be noted that, unlike previous studies on teaching aids and materials, our research offers a more holistic and systemic approach to the analysis and evaluation of DER. We address not only the characteristics of DER and their distribution through digital education platforms, but also the subjectivities and practices of users. Our research offers an integrated methodological approach involving various qualitative strategies, and also incorporates advances in knowledge regarding how these resources are modulated and adapted in school practice. By means of our multi-case studies, we have found that school use of such materials is conditioned by factors external to the teacher (such as the dominant pedagogical culture in the school and the availability of DER in the classroom), as well as individual factors involving teaching methodology, prior experience with analogue/digital materials, and pedagogical beliefs. To some extent, these factors coincide with previous reports on ICT use in schools (Keengwe et al., 2008; Kopcha, 2012) and explain why some teachers continue to predominantly use textbooks and occasionally incorporate digital resources, while other teachers apply a work project methodology where students constantly use a wide range of digital and/or analogue materials. The latter teachers are not only users but sometimes also producers of digital learning materials.

With regard to study limitations and future prospects, the present study could be complemented by additional research. For example, it would be of interest to design and carry out quantitative studies by means of questionnaires to collect descriptive data on the opinions of teachers, pupils and families. Another limitation is that the analysis is limited to a single country: Spain. It would be interesting to extend this analysis to other countries in Europe and other continents in order to allow transnational comparisons and a broader more holistic outlook of the idiosyncratic transformation processes involving digital learning materials throughout the world. Such studies could provide rationale for national education policies regarding the production, dissemination and use of digital learning materials at schools.

Finally, this research provides an approach to the discourse or subjectivity of educational agents regarding digital educational resources and their practices in schools. However, there are still very important questions that the school must address in collaboration with other social agents. Among them, we highlight three: What are the challenges for schools if they want to train the next generations so that students are able to face the challenges of twenty-first century society equipped with values such as social justice, equity and sustainability? What changes should be introduced in the curricula of future teachers and in continuous training in order to have teachers who are not only digitally competent, but who can face the challenges of the twenty-first century school? And in what ways can families be involved in this process by giving them a voice and encouraging their participation?

References

Allen Knight, B. 2019. Textbooks designed for student´s learning in the digital age. In Autor (xxxx), Y.M. Braga Garcia, & É. Bruillard (pp. 385–393) IARTEM 1991–2016: 25 years developing textbook and educational media research. Santiago de Compostela: International Association for Research on Textbooks and Educational Media (IARTEM). https://iartemblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/iartem_25_years.pdf

Al-lmamy, S. Y. (2020). Blending printed texts with digital resources through augmented reality interaction. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 2561–2576.

Area, M. (2020) (Dir.). Escuel@ Digit@l. Los materiales didácticos en la Red. Barcelona: Graó.

Bond, M., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Nichols, M. (2019). Revisiting five decades of educational technology research: A content and authorship analysis of the British Journal of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology BJET, 50(1), 12–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12730

Bottino, R. (2020). Schools and the digital challenge: Evolution and perspectives. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 2241–2259.

Branch, R. M., Lee, H., & Tseng, S. S. 2019. Educational Media and Technology Yearbook: Volume 42. Springer International Publishing.

Bruillard, É. 2015. Digital textbooks: current trends in secondary education in France. In Autor (xxxx), É. Bruillard, & M. Horsley (eds.) (pp. 410–438) Digital Textbooks: What´s New? Santiago de Compostela: IARTEM Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. https://doi.org/10.15304/op377.759

Butcher, N. 2015. A Basic Guide to Open Educational Resources (OER). UNESCO, París. hdl.handle.net/11599/36

Chiu, T. K. F. (2017). Introducing electronic textbooks as daily-use technology in schools: A top-down adoption process. British Journal of Educational Technology (BJET), 48(2), 524–537.

Churchill, D. (2017). Digital Resources for Learning. Springer.

Einav, G. (Ed.). (2015). The new world of transitioned media. Springer.

Engen, B. K. (2019). Understanding social and cultural aspects of teacher´s digital competencies. Comunicar Media Education Research Journal, 61(4), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.3916/C61-2019-01

Fernandes, G. W. R., Rodrigues, A. M., & Ferreira, C. A. (2020). Professional development and use of digital technologies by science teachers: A review of theoretical frameworks. Research in Science Education, 50, 673–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9707-x

Fuchs, E., & Bock, A. (Eds.). (2018). The Palgrave handbook of textbook studies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Gopal, V. (2020). Digital education transformation: A pedagogical revolution. i-manager’s Journal of Educational Technology, 17(2), 66–82.

Grönlund, Å., Wiklund, M., & Böö, R. (2018). No name, no game: Challenges to use of collaborative digital textbooks. Education and Information Technologies, 23(3), 1359–1375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9669-z

Hákansson Lindqvist, M. (2019). Talking about digital textbooks. The teacher perspective. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(3), 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-11-2018-0132

Keengwe, J., Onchwari, G., & Wachira, P. (2008). Computer technology integration and student learning: Barriers and promise. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17, 560–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-008-9123-5

Kim, D., Lee, I. H., & Park, J. H. (2019). Latent class analysis of non-formal learners’ self-directed learning patterns in open educational resource repositories. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(6), 3420–3436.

Kohout-Tailor, J., & Sheaffer, K. E. (2020). Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 32(1), 11–18.

Kopcha, T. J. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development. Computers & Education, 59, 1109–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.05.014

Lane, A., & y MacAndrew P. (2010). Are open educational resources systematic or systemic change agents for teaching practice? British Journal of Educational Technology BJET, 41(6), 952–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01119.x

Li, J. Z., Nesbit, J. C., & Richards, G. (2006). Evaluating learning objects across boundaries: The semantics of localization. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 4(1), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.4018/jdet.2006010102

Magdas, I., & Dringu, M. C. (2016). Primary school teachers’ opinion on digital textbooks. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 9(3), 47–54.

Mahapatra, S. K. (2020). Impact of digital technology training on english for science and technology teachers in India. RELC Journal: A Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 51(1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220907401

Marcus-Quinn, A., & Diggins, Y. (2013). Open educational resources. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.183

Mardis, M., & Everhart, N. (2015). The promise and Challenge of Digital Textbooks for K-12 Schools: The Case of Florida´s Statewide Adoption. In J. Rodríguez, É. Bruillard, & M. Horsley (eds.) (pp. 306–369) Digital Textbooks: What´s New? Santiago de Compostela: IARTEM Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. https://doi.org/10.15304/op377.759

Marsh, J., Hannon, P., Lewis, M., & Ritchie, L. (2017). Young children´s initiation into family literacy practices. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 15(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/147676718X15582095

Nedungadi, P., Menon, R., Gutjahr, G., Erickson, L., & Raman, R. (2018). Towards an inclusive digital literacy framework for digital India. Education & Training, 60(6), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2018-0061

OECD (2007). Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources., Paris: OECD Publishing /dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264032125-en

Palacios, F. J., Gómez, M. E., & Huertas, C. A. (2020). Digital and media competences: Key competences for EFL teachers. Teaching English with Technology, 20(1), 43–59.

Reints, A., & y Wilkens, H. (2014). The quality of digital learning materials. UNESCO-IHE, Kennisnet, english edition.

Reints, A. J. C., & Wilkens, H. J. 2019. How teachers select textbooks and educational media. In Author (xxxx), Y.M. Braga Garcia, & É. Bruillard (pp. 99–109) IARTEM 1991–2016: 25 years developing textbook and educational media research. Santiago de Compostela: International Association for Research on Textbooks and Educational Media https://iartemblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/iartem_25_years.pdf

Rossignoli, C. Virili, F., & Za, S. (eds.) 2018. Digital Technology and Organizational Change: Reshaping Technology, People, and Organizations Towards a Global Society. Springer International Publishing.

Sancho, J. M. 2009. ¿Qué educación, qué escuela para el futuro próximo? Educatio Siglo XXI, 27(2), 13–32, http://revistas.um.es/educatio/article/view /90931

Sumardi, L., Rohman, A., & Wahyudiati, D. (2020). Does the teaching and learning process in primary schools correspond to the characteristics of the 21st century learning? International Journal of Instruction, 13(3), 357–370.

Sunkel, G. 2012. Buenas prácticas de TIC para una educación inclusiva en América Latina. In G. Sunkel & D. Trucco (Eds.), Las tecnologías digitales frente a los desafíos de una educación inclusiva en América Latina. Algunos casos de buenas prácticas. Santiago de Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL) / Naciones Unidas. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/35382

Weng, C., Otanga, S., Weng, A., & Cox, J. (2018). Effects of interactivity in E-textbooks on 7th graders science learning and cognitive load. Computer & Education, 120, 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.008

Wikman, T. 20xx. In Author. To be added following double-blind review.

Wiley, D. (2000). Connecting learning objects to instructional design theory: A definition, a metaphor, and a taxonomy. Learning Technology, 2830, 1–35.

Wiley, D. 2008. The Learning Objects Literature. In D. Jonassen, M.J. Spector, M. Driscoll, D. Merrill, & J. Van Merrirnboer, & D. Discoll (eds.). Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 3º ed. Taylor and Francis.

Wiley, D., Bliss, T. J., & McEwen, M. (2014). Open educational resources: A review of the literature (pp. 781–789). Springer.

Xie, K., Di Tosto, G., Chen, S. B., & Vongkulluksn, V. W. (2018). A systematic review of design and technology components of educational digital resources. Computers and Education, 127, 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.011

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage Publication.

Zawacki-Richter, O., & Latchem, C. (2018). Exploring four decades of research in Computers & Education. Computers & Education, 122, 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.001

Zwart, D. P., Van Luit, J. E. H., Noroozi, O., & Goei, S. L. (2017). The effects of digital learning material on student´s mathematics learning in vocational education. Cogent Education, 4, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1313581

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This article is derived from the research project entitled “The school of the digital society: analysis and proposals for the production and use of educational digital content” EDU2015-64593-R funded by the State Program for Research, Development and Innovation Oriented to the Challenges of the society. Call 2015, Ministry of Science, Government of Spain, and Rosa M. Alonso Program of Tenerife Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Interviews conducted in study 1

Education Primery Teachers | 6 discussion groups of teachers (between 6–10 teachers participated in each group) In total: 48 subjects |

|---|---|

Technicians or experts | 10 individual interviews with private editorial managers and 3 with those responsible for institutional portals. In total 13 interviewees |

Families | 6 discussion groups of fathers and mothers (between 4–7 people participated in each group) In total: 32 subjects |

Appendix 2: Instruments for data collection and dimensions analyzed in the case studies of the schools in study 2

Instruments | Classroom | Center | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Organizational dimension | Didactic dimension | Student learning dimension | Organizational dimension | Pedagogical dimension | |

Field diary | √ | √ | |||

Unstructured or narrative classroom observation | √ | √ | |||

Semi-structured individual interviews | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

group interviews semi-structured | √ | √ | √ | ||

Protocol for the analysis of didactic programs | √ | ||||

MDD Analysis Protocol | |||||

Document Analysis | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

Appendix 3: Dimensions and indicators for analysis in the multicase study of schools

Dimensions | Indicators |

|---|---|

Group-class level | |

Organizational How are technological resources organized and managed in the classroom? | Number and location of tablets/laptops and other hardware |

Materials and software used | |

Organization of space | |

Online resources used and created | |

ICT Plan / PGA of the center / other documents | |

Didactic What is taught? What kind of tasks or activities are developed? What materials are used in the classroom? | Contents worked with ICT and other teaching materials, and format adopted (disciplinary/integrated) |

Materials used (digital and non-digital) | |

Didactic planning of experiences or activities with ICT | |

Types of activities developed | |

Ways to group and organize students | |

Communicative interactions teacher-students and students with each other | |

Student learning What do students learn and what skills do they develop when working with ICT? | Levels of development of digital competence |

Motivation and attitudes of students towards learning in general, and towards learning with ICT | |

Dimensions | Subdimensions |

Center level | |

Organizational | Visibility of the center on the Internet |

Communication with families and participation of the AMPA in the ICT policy of the center | |

Use of ICT for communication and teaching coordination between teachers | |

Use of ICT for administrative and management tasks | |

Pedagogical | Own projects developed by the center with ICT |

Online educational networks | |

Modalities of ICT use in face-to-face and/or virtual teaching–learning processes | |

Production and management of digital resources for teaching and learning | |

Appendix 4: Script interviews

Group interview with teachers

Group component identification data.

Sex, age, course taught, ownership of the center where you work, contract profile: provisional, definitive… |

Assessment of digital teaching materials.

Do you consider that the use of digital teaching materials at school is important? Why? |

What materials do you prefer: traditional didactic materials (paper textbooks, worksheets, manipulative materials,…) or digital didactic materials? Because? |

How do you rate digital textbooks versus paper textbooks? |

What is your opinion of the formal and pedagogical characteristics of digital teaching materials (personalization of learning, contextualization of teaching, attention to diversity,…)? |

What are the advantages of using digital resources for student learning? |

What difficulties does the use of digital resources have for student learning? |

What materials do your students prefer: traditional teaching materials (textbooks on paper, worksheets, manipulative materials,…) or digital resources? Why? |

Use of digital teaching materials.

What type of digital didactic materials, digital services and applications do you usually use in your classes? Why? So that? In what subjects? At what moments in the teaching–learning process? |

How do you use digital teaching materials in your classroom? Give some examples |

What problems or difficulties have you encountered while using digital teaching materials? |

How do you combine the use of textbooks and digital materials in your teaching practice? |

Do you consider that digital teaching materials facilitate communication with students? And with family?, in what way? |

Do you think that digital teaching materials can facilitate coordination or shared work with your classmates? In what way? |

Do you carry out any kind of evaluation of the digital teaching materials you use? With what criteria? |

Training received.

What type of training have they received for the use of digital teaching materials ? |

Have you received for the creation of digital teaching materials ? |

To what extent do they feel prepared to develop teaching and learning processes with digital resources? |

Organizational context.

What changes have been introduced in the organization of the center to use digital teaching materials ? |

In the event that your center has chosen a platform for digital teaching materials, what criteria have you used to select it? |

Economic dimension.

Does the economic cost of digital resources influence the use they make with their students? (If yes, in what way?) |

Group interview with families

Group component identification data.

Sex, number of children, courses your children are taking, town of origin, center where the children go, ownership of the center,… |

Assessment of digital teaching materials.

Materials (textbooks on paper, index cards, manipulative materials,…) or digital didactic materials, what do you think about it? (What do you think of digital textbooks? Do you think that digital textbooks have improved over printed textbooks?) |

Do you think your children improve motivation when doing homework with digital teaching materials? |

Do you think that the use of digital teaching materials favors the distraction of school tasks? Why? |

Why do you think that part of the teaching staff is increasingly opting for the use of digital teaching materials ? |

Are they beneficiaries of aid from free programs for textbooks or digital teaching materials? (If so, what type of aid are they beneficiaries of? How is it assessed?) |

Use of digital teaching resources.

What is your role in relation to digital teaching materials: (accompaniment, use, participation in the design process,…)? |

Do you have difficulties to keep track of the school tasks of your sons and daughters that require the use of digital teaching materials? (If so, what difficulties do they have?) |

In addition to school digital teaching materials, do your children use other non-school digital teaching materials ? (If so, what materials do they use? And what do they use them for?) |

To what extent have digital teaching materials facilitated communication between students and teachers? And between teachers and family? |

Economic dimension.

What technological devices do you have at home (tablets, computer,…)? |

Have you had to buy digital devices for your sons and daughters at the request of the school? (If so, which one(s)?) |

Do you think that the price of these materials and devices is affordable for the majority of the families in your center? |

What do you think about the cost of digital teaching materials compared to what traditional textbooks cost? |

Interview with editors

Identification data.

Professional profile of the interviewee |

Editorial portal type |

Organization of the web portal.

How was the portal created? Describe the design and development of the portal |

Do they develop dissemination strategies for the portal? (If so, what strategies do they use?) |

How is the portal organized? What services do you offer? |

What kind of access do you have? (open, limited to users; paid, free…) |

Creation of digital teaching materials or resources.

Who are the authors of the materials published on the portal? What professional profiles do they have? |

Are there interdisciplinary work teams for the creation of the digital teaching materials offered by the portal? (If so, who are they?) |

What criteria have you followed for the creation or selection of materials? |

What is the process (steps) for creating the digital materials incorporated into the portal (initial idea, planning, prototyping, experimentation, reworking, publication, dissemination)? |

Materials evaluation.

What criteria and procedures are used to evaluate the portal and the digital teaching materials it offers? |

Do you have data on the use of the portal by different users? (If so, what kind of data? Could you provide it to us?) |

Do they use this data? What do they use it for? |

Do you have data on the profile of the educational centers that use your digital teaching materials? |

Pedagogical dimension.

What is the educational model used in the portal? |

What are the pedagogical and technological characteristics that the materials must have? Who decides them? And with what criteria? |

Economic dimension.

What type of licenses do you use? |

Do you carry out any market study before launching a new digital teaching material? |

Overall rating.

What role do companies play in the production of materials? What about public institutions (educational administrations, local administrations,…)? (What do they contribute in the educational context?) |

What is the future of didactic materials? Paper textbook or digital materials? |

Are the teachers prepared to use the digital didactic material ? And the families? |

Appendix 5: Interviews analysis process

-

1.

Information recording The information produced by the individual or group interviewee was recorded requesting permission from the participants.

-

2.

Transcription After finishing the interview, the recorded audio was converted into text using a computer application.

-

3.

Coding On the transcribed text, the first task consisted of coding segments of information (phrases, paragraphs) based on a series of symbols, abbreviations or codes that were more or less representative of the content about which the interviewee talks.

-

4.

Categorization This phase consisted of establishing a series of categories or dimensions of analysis, which represent a second level of abstraction, higher than that of the previous coding. In our case, the categories were previously defined:

Faculty

Student body

Families

Commercial and institutional publishers

Valuation of the DTM

Valuation of the DTM

Valuation of the DTM

portal organization

Use in teaching

Personal use

Use of DTMs

Creation of DTM

Training available on DTM

Academic use

Economic influence

DTM Assessment

Organizational context

Pedagogical model

Economic influence

economic influence

DTM rating

DTM Digital Teaching Materials

-

5.

Preparation of matrices The matrices were double-entry tables where the dimensions or categories of analysis were identified horizontally, and the subjects vertically. Four levels of matrices were made:

-

Level 1: Preparation of Question Matrices that synthesize the responses of each subject/group to each question asked.

-

Level 2: From the previous table, another Table or Matrix of categories is prepared that represent or synthesize what is expressed by each agent based on the categories identified.

-

Level 3: Comparative matrices between agents . This matrix is built as a synthesis of all of the above. It was a single double-entry table (matrix) where each type of agent (Teachers, Students, Families and Editors) appeared vertically, and the different categories of the interviews vertically. comparative matrix of the results at the national level was prepared , where each of them included the results of the three autonomous communities (Canary Islands, Galicia and Valencia) in each of the categories of the different educational agents.

-

Appendix 6: Descriptive data of the participating schools

Case | Galician 1 | Galician 2 | Canaries 1 | Canaries 2 | Canaries 3 | Valencia 1 | Valencia 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ownership | Public | Public | Public | Public | Concerted Private | Public | Concerted Private |

Setting: area socioeconomic level of the student body | semi-urban Medium level | Rural Medium–low level | Has changed from rural to increasingly residential The level has increased | Urban environment Medium–high level | Between three poor neighborhoods of an urban area medium–low level | Urban Medium level | Urban medium–low level |

Size | 390 students | 140 students | 266 students | Between 430 and 450 students | More than 1,000 students | 221 students | 666 students |

32 teachers | 27 teachers | 20 teachers | 27 teachers | 68 teachers | 17 teachers | 52 teachers | |

Management team made up of 3 people | Management Team: 4 people | Management Team: 3 people | Management Team: 4 people | Management Team: 8 people | Management Team: 3 people | Management Team: 5 people | |

Specific infrastructures | institutional server | institutional server | institutional server | institutional server | own server | institutional server | own server |

Library as a space to stimulate the use of ICT | Library as a space to stimulate the use of ICT | Two classrooms (press and radio projects) | Scholar Orchard | The students of each level are located in a “ superaula” | Computer room not used by 5th and 6th | cart with laptops | |

Computer room | |||||||

Hallmarks | Support from the management team for ICT initiatives | Promotes innovative methodologies | Participation in innovative projects on their own initiative; some with roots | Several projects with ICT | Clear ICT policy driven by management | Shared leadership | Promotion of innovation |

Great experience and teacher training in ICT | High visibility on the network | Elimination of textbooks in the center and the use of an active and globalizing methodology | The management team promotes the use of ICT | Support for ICT and innovative pedagogies | Innovative school | Several projects with ICT | |

Progressive elimination of the printed textbook and replacement by Digital Teaching Materials (DTM) | ICT integration policy assumed by the educational community | Elimination of textbooks in Primary | Elimination of the textbook in 5th and 6th | Teachers adapt and create DTM | |||

Teachers and students adapt and create MDD | Leadership of the management team to work with ICT | Teachers and students adapt and create DTM | Creation of curricular materials | ||||

Teachers and students adapt and create DTM | Teachers and students adapt and create DTM |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Area-Moreira, M., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J., Peirats-Chacón, J. et al. The Digital Transformation of Instructional Materials. Views and Practices of Teachers, Families and Editors. Tech Know Learn 28, 1661–1685 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09664-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09664-8