Abstract

The study examined what factors determine the use of educational innovations by teachers in higher education. Three sort of factors were compared: teachers’ motivation for the enhancement of education, their contact with or exposure to dissemination of educational innovations and institutional factors, that is, support provided by higher education institutions. Further, teachers were classified regarding their use of educational innovations. The study used survey data collected among academic staff at public Norwegian higher education institutions. Results of the multinominal logistic regression models showed that intrinsic motivation was an important factor for teachers' innovation behaviour in this context. Dissemination and institutional factors exerted little or no significant impact. The assumptions currently underlying research on educational innovations and the design of national and institutional support programmes are discussed against the background of these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In some models of educational change, the adoption of educational innovations by teachers is an important driver of change (Elmore, 1996; Kezar, 2011). Accordingly, several studies have investigated the factors that encourage teachers to adopt educational innovations (Khatri et al., 2017). Most of this research has been based on Rogers' diffusion of innovation theory and its main idea that rational actors will adopt innovations that have added value compared to traditional practices (Rogers, 2003). Against this background, the research examined factors that play a role in the decision process of potential adopters of innovations, including incentives, information dissemination, motivational aspects, and (institutional) measures to support and enhance teachers' capacity to use the adoption (e.g. Baas et al., 2019; Bajada et al., 2019; Khatri et al., 2017; Stanford et al., 2016).

However, there are still several questions that need to be answered. Some studies report that teachers mutate educational innovations once they have been adopted (McKenney & Reeves, 2017), others point out that teachers are unaware of whether and how they have used educational innovations when designing their teaching, so there could also be dark reuse of educational innovations as Beaven (2018) found for the use of Open Educational Resources. To date, most studies seem to define the use of educational innovations as a binary outcome, where teachers use the innovation or not while not addressing uses which consider their adaptation or mutations (McKenney, 2014), and not considering their unconscious use.

The aim of this study is to identify the use of educational innovations by teachers who were not involved in development of the innovations, and to what extent factors such as motivation, dissemination and institutional support stimulate the use. The study results are relevant for the design of future teaching enhancement initiatives that aim to diffuse educational innovations beyond the context in which they were created.

These questions are being investigated for the Norwegian teaching excellence initiative "Centres for Excellence in Education" (CEE), which aims to improve the quality of teaching and learning through the development and dissemination of excellent educational innovations developed by the funded CEEs throughout the Norwegian higher education sector. Against this background, the study aims to answer the following research questions:

-

To what extent does teacher motivation to engage in educational enhancement correlate with their propensity to adopt educational innovations?

-

To what extent do dissemination activities for educational innovations correlate with the propensity to adopt them, and do they change teachers’ motivation?

-

To what extent do institutional factors such as cultures, strategies and the provision of support stimulate teachers’ propensity to adopt educational innovations? Do these institutional factors change teachers’ motivation?

The Norwegian Initiative “Centres for Excellence in Education” – the SFU Initiative

This study was conducted in the context of a specific Norwegian initiative: The Norwegian Centres for Excellence in Education initiative. It started in 2010 and was still ongoing at the time of writing (2023). The initiative was launched by several stakeholders in higher education, such as the Norwegian Ministry of Education or the Norwegian University Council (UHR). A key goal of the CEE initiative is to encourage higher education institutions (HEIs) to become more involved in educational tasks, to raise the status of teaching and learning activities, and to make them as important as research activities (Andersen Helseth et al., 2019; NOKUT, n.d.).

To this end, the initiative funds disciplinary Centres for Excellence in Education (CEE) at Norwegian HEIs. The Centres are intended to act as innovation hubs for their disciplines in order to stimulate the improvement of education across Norway and even internationally. To this end, the CEEs are expected to develop educational innovations in a research-based manner and to disseminate these innovations within and beyond their host institutions. Thus, an important goal of the initiative is to create educational innovations that will be adopted by teachers who were not involved in a CEE. Currently, 12 CEEs are operational and funded, involving Centres that have already started their work in 2010.

Concerning their design, the CEEs can be considered as Network Centres for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (Kottmann, 2017, Kottmann, 2023) which are Centres that have established themselves as a group with slightly formalised structures within a faculty. These Centre are run by academics from the faculty with a small number of educational specialists supporting their work.

The CEEs’ theory of change, i.e. the assumptions about why CEEs should stimulate educational change within and beyond their institutions can be classified as an exemplar approach, which is “…based on a contagion model of change, which assumes that if the best individuals, departments, or institutions can be identified and rewarded, then they will share their excellent practices and help to encourage others to become excellent.” (Ashwin, 2020, p. 10) Accordingly, CEEs were required to demonstrate in their applications that they had already successfully engaged in educational enhancement activities and what their collaborative dissemination strategy would be.

Evaluations found that the CEEs developed a variety of educational innovations and stimulated awareness for educational enhancement across the Norwegian higher education sector (Kottmann et al., 2020; Andersen Helseth et al., 2019). These innovations included, for example, practices such as project-based learning, flipped classroom approaches or digital support for assessments and examinations. Apps to support students in their learning were also developed as well as promotion schemes for teachers, which were acknowledged across Norway.

However, the educational innovations did not seem to achieve the intended impact. A survey among teachers who did not participate in the CEE’s activities revealed that teachers who reported having changed their teaching practices in the recent past made little use of the CEE innovations. Only a minority of them adopted innovations when changing their teaching practice, others reported that they adapted or observed these educational innovations. Several teachers reported that they did not know whether and to what extent their change in teaching practice was influenced by the CEEs’ innovations or other resources (Kottmann et al., 2020). There seems to be a lack of use of the educational innovations developed by CEE’s, and the question here is why this is the case.

Literature Review

Use of Educational Innovations

Most studies on how teachers use educational innovations distinguish between adopters and non-adopters and do not clearly define what the adoption of an educational innovation entails, i.e. whether it is used for its originally intended purpose (Scott & McGuire, 2017; Smith, 2012; Stasewitsch et al., 2021; Warford, 2017).

Research on the (re-)use and adoption of Open Educational Resources (OER), which can also be considered as educational innovations, has provided typologies that classify users in terms of how and to what extent they adopt the resources. This research has shown that full adoption is the exception rather than the rule (Beaven, 2018; Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2019; Schuwer & Janssen, 2018).’Admiraal’s study (2021) distinguished five user types, ranging from users who mostly consume OER to users who strongly engage with the resources, i.e. modify, adapt, and (re-)publish them. Beaven (2018), in her study of teachers’ use of OER shows that this use is often dark re-use, where teachers do not share with the source repository if and how they have been using the resources. A major barrier to re-sharing the use of OER is that they are only one of many resources that teachers use in their teaching. Frequently, OER are combined with other resources, such as material from their colleagues, textbooks or own ideas. In this process, the identity of the OER becomes blurred making it difficult for teachers to accurately recall and report the origins and modifications of the resources they use (Beaven, 2018, p. 387).

Factors Stimulating the Use of Educational Innovations

Motivation

Concerning the motivation of teachers a few studies have looked at the impact of external incentives such as extra renumeration or teaching awards and prizes on teachers’ motivation to use educational innovations (Henke & Dohmen, 2012; Machado et al., 2011; Wilkesmann & Schmid, 2012). Distinguishing between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation studies found that factors that stimulate extrinsic motivation, such as merit pay or performance-based funding, did not lead to the desired increase of teacher engagement. Rather, teachers were more likely to be involved in improving teaching if the values underlying the educational innovations matched their own. These findings support that intrinsic motivation is a vital source of engagement for good teaching, playing a more significant role than extrinsic motivation (Esdar et al., 2016).

A detailed account of the importance of intrinsic motivation for the engagement in educational innovation is provided by Stupnisky et al. (2018). In their study of the role of motivation in the adoption of best teaching practices by faculty at US colleges and universities, they applied Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory. The findings also indicated that intrinsic motivation was the strongest predictor of faculty commitment to best practices. However, the impact of intrinsic motivation depended on contextual factors, such as collegiality or clarity of the best practice and the extent to which the behaviour was related to teachers’ basic psychological needs such as their desire for autonomy or relatedness. The study results showed that teachers who worked in contexts that satisfied their need for autonomy and allowed for self-determined behaviour were more likely to use the best teaching practices offered to them. In contexts that did not meet teachers’ autonomy needs and where external regulation prevailed teachers were less likely to change their practices. Furthermore, the study found that external factors such as rewards or introjected guilt were not related to teachers’ basic psychological needs and therefore did not motivate teachers to use the best practices offered to them (Stupnisky et al., 2018, p. 23).

Dissemination Activities

The way in which educational innovations are disseminated is a second factor that has been found to be relevant for encouraging teachers to use them. Accordingly, some national initiatives to improve teaching require specific dissemination plans that ensure the spread of educational innovations developed by the initiative (Andersen Helseth et al., 2019; Khatri, 2018; Stanford et al., 2016; Stanford et al., 2017).

These requirements and studies of the impact of dissemination on the adoption of educational innovations are primarily rooted in Rogers’ ‘Theory of Diffusion of Innovations’ (Rogers, 2003). Its central assumption is that potential adopters are rational actors who are more likely to adopt an educational innovation if they perceive it as more useful than their old practices and do not associate high risks with its use. Therefore, dissemination strategies promoting educational innovations need to persuade potential adopters; that is, they should provide useful information so that users can assess the costs and benefits of the innovation.

Research on the impact of dissemination strategies has shown that disseminating information about the educational innovations in a passive format, that is through publications, websites or knowledge repositories does not reach a significant number of adopters (Andersen Helseth et al., 2019, Ashwin, 2022). Rather, these strategies need to be carefully designed to stimulate teachers’ interest and the adoption of an educational innovation. For example, Stanford et al. (2016) found that dissemination strategies are more likely to succeed if they focus on the concerns of potential users and provide information that addresses their uncertainties and encourages them to use the educational innovation (see also Stanford et al., 2017). These studies have also shown that educational innovations, which may require a change in teaching practice and teachers’ core beliefs or values, can cause considerable uncertainty among teachers. To reduce this uncertainty, the disseminated information addresses the needed changes or how to adapt the educational innovation to teachers’ needs (Scott & McGuire, 2017; Smith, 2012). Providing potential users with opportunities for collaboration and support when engaging with the innovation was also a strong factor for successful dissemination.

Institutional Characteristics

Finally, institutional characteristics may influence teachers’ use of educational innovation. These characteristics can act as barriers or enablers to teachers’ innovative behaviour. Three categories of such institutional characteristics, including cultural factors, institutional strategies, and the provision of resources that HEIs use to stimulate educational improvement among their teachers, are relevant to discuss here.

Cultural Factors

Cultural factors relate to values and communication in HEIs in the context of educational activities. As loosely coupled and professional organisations, HEIs often do not have a set of educational values that provide a strong consensus for the orientation of educational activities (Trowler, 2020). Rather, HEIs have a multiversity of academic microcultures located at the level of disciplines, departments or groups (Harvey & Stensaker, 2008; Roxå & Mårtensson, 2013). These microcultures vary in their openness to external influences which determines how teachers approach the quality of education and the use of educational innovations. Open microcultures give teachers more freedom to change their teaching practices and adopt educational innovations while more restricted cultures limit these opportunities (Dee & Leisyte, 2016).

Some studies have shown that institutional management can influence these microcultures through leadership, implementing collaboration between teachers across disciplinary or departmental structures and facilitating institution-wide communication about educational activities (Roxa & Martensson, 2008). Such interventions can create an institutional culture that values educational innovation. Lašáková et al. (2017) highlighted that an open culture and a high degree of academic freedom are most effective when internal collaboration and communication crosses disciplinary and faculty boundaries. Smith (2012) also pointed out that institutions that introduce mentoring groups or communities of practice create more openness towards educational innovation. Further, the combination of institutional cultures and leadership styles that are open to change with the presentation of many adopters of educational innovations adopters can be a key to opening up more siloed departmental cultures (Warford, 2010). Wilkesmann and Lauer (2020) found that didactic support, space for sharing experiences with colleagues and the availability of student feedback create cultures that support teachers in educational innovation.

Institutional Strategies and Provision of Resources

Prior research has discerned that the support and strategies of institutions are relevant for the use of educational innovations (Admiraal, 2021; Baas et al., 2019). Institutional strategies are interventions that aim to create conditions in which educational innovations can be implemented or teachers can be enabled to change their teaching practices (Lašáková et al., 2017). These interventions include the provision of the necessary technical infrastructure and training to increase teachers’ capacity to use the innovations. Lašáková et al. (2017) reported that institutions in which management and leadership have detailed strategic planning and establish new, additional structures and roles for the envisaged change can create more acceptance for educational innovations. Management and leadership that act as role models can also stimulate changes in behaviour among staff.

The provision of resources such as time and funding by the higher education institutions seems to be essential institutional support for teachers who want to change their teaching practice. In particular, the provision of release time for teachers to develop their teaching practice can serve as an enabler. (Lašáková et al., 2017; Millard & Hargreaves, 2015).

Framework, Data and Methods

Sample and Data, Survey Instrument

This study makes use of a dataset established as part of an evaluation of the above-mentioned Norwegian initiative ‘Centers of Excellence in Education’. Among other types of data collection, this evaluation conducted a survey of academic staff and staff with a managerial role in education from Norwegian HEIs in the summer of 2019. In total, teachers from nine research universities (out of a total of 10), seven specialised universities (out of a total of 9), and four universities of applied sciences or university colleges (out of a total of 13) participated. The survey reached out to those teachers and staff who were not involved in a CEE and who could therefore be potential adopters of their outputs and innovations.

The subsample analysed in this study consists of respondents who indicated that they were actively teaching. Table 2 in the Appendix provides full details of the subsample.

The representativeness of the sample cannot be fully determined because the survey applied different categories than those used in official statistical data (Norsk Senter for Forskningsdata, 2020, p. 38), Therefore, the survey sample is difficult to compare to the overall population of academic staff in Norway for this characteristic. The only variable that can be compared is gender: While the official data reports that 54% of all academic staff in Norway were female in 2019, this percentage was 43%, in the sample used in this study.

The survey instrument was specifically designed to evaluate the CEE initiative. With the exception of questions that collected information on the respondents’ disciplinary background, the research team developed all questions and scales themselves. The survey was piloted with a few experts before its launch for comprehensibility. Prior to the analysis, the data were pre-processed to measure the framework variables (see below). Information on the reliability of the pre-processed scales is provided in the Supplementary Data File. The survey language was English.

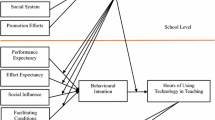

Analytical Framework and Operationalisation of Measurements

The findings from the literature review were used to develop the analytical framework that guided the data analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. As a first step, the analysis tested the extent to which motivation predicts the use of CEE’s innovations by respondents. Intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of motivation were included. The second analysis tested how strongly motivation and dissemination determined the typical use of CEE’s innovations. This analysis included contact with CEE information and the evaluation of the costs and risks of using the innovation. The third analysis looked at how strongly the variables motivation and institutional characteristics determined the typical use of CEE’s innovations, which included cultural factors, institutional strategies and the provision of resources.

Dependent Variable – the Typical Uses of the CEEs’ Educational Innovations

The dependent variable aims to distinguish typical uses of CEEs’ educational innovations by teachers. Given that research has found that teachers to adopt, adapt, consume or even unconsciously use educational innovations, the user-type variable needs to provide categories for these types of behaviour. We used three questions from the survey in which teachers reported on changes of their teaching practice, their awareness of the CEEs and if they had used their educational innovations. Descriptives of these variables are included in Appendix 2. Figure 2 below shows the decision tree that was used to classify respondents for their typical use of CEE innovations.

Independent Variables

For each of the three main blocks of independent variables, survey questions were identified to measure them. Unless otherwise stated, all variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘not at all’ to 5 ‘to a large extent’. The descriptives for the independent and the control variables are presented in Table 1. The reliability scores for the scale variables are included in the Data Appendix.

Motivation

Two questions were combined to measure intrinsic motivation. The first question asked about the respondents’ wish to try out new approaches to teaching, and the second about the extent to which their personal interest in improving their teaching skills had stimulated their engagement in teaching improvement. The second question related to the respondents’ individual importance of teaching enhancement. All of these scores were combined as a mean.

Responses to four questions measure extrinsic motivation. The first variable ‘Motivation by incentives’ includes the respondents’ evaluations of the extent to which the provision of time and funding had incentivised them to change their teaching practice. The second variable ‘Motivation by colleagues’ captured the influence of colleagues’ recommendations for more innovative teaching stimulated the respondents. The third variable was respondents’ perceptions of the value of the importance of educational enhancement in their units and fourth variable considered the institutional influence.

Impact of Dissemination

In order to include the impact of dissemination in the analysis, two aspects were measured. The first aspect was the respondents’ contact with the dissemination of CEE’s results, which included responses to two questions: The contact frequency and its relevance to the respondents.

The second aspect was how the respondents perceived the CEE innovations in terms of the costs and risks of using them. Three items were used here. The first was the rating of the extent to which they would have to change the innovation in order to use it. Second was their expectation of the extent to which they would need to change their teaching practice to use the innovation. The third was their rating of how strongly they would need to collaborate with the CEEs to implement the innovations.

Institutional Factors

Three sets of variables – cultural factors, institutional strategies and provision of resources – were included to measure the influence of institutional factors.

Two questions were used to capture cultural factors. The first averaged teachers’ ratings of the openness of the institutional culture to educational innovation and of the leadership support provided for adopting these innovations. The second question represented the extent to which teachers perceived a change in the value of educational activities in HEIs over the past five years.

The measurement of institutional strategies used the mean of respondents’ responses to three items asking how well the institutional infrastructure, students, staff and other teaching structures were prepared to adopt educational innovations.

Concerning provision of resources, the respondents’ assessments of the availability of time and funding were used.

Control Variables

The analysis also included gender, the professional role of the respondent, the number of years they had worked in their current job, and their disciplinary area as control variables.

Analysis

As the dependent variable represents nominal data, multinominal logistic regression models were used to estimate how strongly the independent variables influence the respondents’ typical use. A preliminary analysis revealed that, despite the nested structure of the data, with teachers being staff of HEIs, the respondents’ institutional affiliation had no significant effect on the distribution of the independent and dependent variables. Therefore, multilevel analysis was not necessary.

A separate model was calculated for each of the three research questions. The first model analysed the influence of motivation, the second combined motivation and dissemination, and the third model considered the influence of institutional support and motivation. The samples included in each analysis are different. This is due to the way in which respondents were guided through the questionnaire. For example, respondents who did not change their teaching practices were not asked about their motivation for doing so. Similarly, respondents who indicated that they were not aware of the CEE initiative did not have to answer the questions about how often they had contact with the dissemination of the initiative or how relevant this information was to them.

In line with this, non-users were excluded from all analyses, due to their not providing information on the independent variables. Users that were identified as Autonomous Innovators were not considered in the model that estimated the effect of contact with/exposure to dissemination, as those respondents indicated not having had this. In the results section below, it will be described in more detail below which user types had been included in the analysis. Table 1 below also informs about which data were available for the user types.

Results

Typical Uses of Educational Innovations Among Teachers at Norwegian Higher Education Institutions

Using the decision tree shown in Fig. 2 revealed the distribution of the typical uses of CEE innovation among the surveyed teachers. The majority of the sample, 305 respondents, were classified as Adapters; the second largest group, 198 respondents, were Autonomous Innovators. There were 61 Adopters, 72 Observers, and 81 Non-Users. These groups differed significantly with regard to the independent variables (see Table 1). On average, the highest values were found among the Adopters; they scored highest for all types of motivation, on the importance they attached to educational enhancement and the openness of the institutional culture, and on their contact with/exposure to dissemination. There were few differences between Adapters and Autonomous Innovators except for contact with dissemination, which did not apply to Autonomous Innovators. Observers had the lowest mean values for all types of motivation and their evaluation of the importance of educational enhancement.

The Influence of Motivation

The forest plots in Figs. 3, 4 and 5 below present the results of the multinominal regression. The circles represent the regression coefficients (beta) for all independent variables, the whiskers their standard error (se). Negative values of beta point out that the independent variable has a negative influence, beta-values around zero point out that the independent variable has a very low or no influence, positive beta-values indicate that the independent variable has a positive influence.

The analysis revealed that intrinsic motivation and the individual importance of educational enhancement were significant predictors of all three active adoption styles (see Fig. 3). In particular, intrinsic motivation was a strong predictor of being an Adopter. It also had a significant but less strong role in predicting the other two types of innovators. However, variables related to extrinsic motivation were not significant predictors of teachers’ adoption styles.

The Influence of Dissemination

The analysis of the impact of dissemination compared Adopters with Adapters (see Fig. 4). The other styles could not be included because they did not answer these questions in the survey.

In terms of contact with CEE information, the frequency of hearing about specific CEEs was a strong and significant factor. Teachers who reported a high frequency of hearing about specific SFUs were more likely to be Adopters. The relevance of the information to their work did not play a significant role.

Adopters and Adapters differed clearly in their evaluation of the costs and risks associated with using educational innovations from CEEs. The expectation that innovations would require a high degree of modification strongly reduced the likelihood of being an Adopter. On the other hand, expecting a high level of change in teaching practices strongly increased the likelihood of being an Adopter. When adopting innovations, Adopters and Adapters differ in what they want to change in order to use the innovation. Adopters primarily see the need to change their teaching practices in order to use the innovation. Adapters, on the other hand, seem to focus more on changing the innovation to meet their requirements.

However, the motivational variables, did not have a significant impact when the impact of dissemination was added to the model.

The Influence of Institutional Characteristics

None of the institutional characteristics that were included in the third model were found to have a significant impact on teachers’ adoption style (see Fig. 5). Instead, the analysis revealed that the individual importance of educational enhancement was a strong determinant of innovative behaviour for all three adoption styles. When comparing the results for the impact of the individual importance of educational enhancement with those from the first analysis (see Fig. 3), we find that its effect is even stronger.

Conclusion

This study investigated factors that determine how teachers use educational innovations to change their teaching practice: their motivation, the dissemination of information about the innovation and institutional characteristics that may facilitate or hinder the use of educational innovations. While previous research has often addressed only one of these factors, this study was particularly interested in how teacher’s motivation is influenced by dissemination or institutional characteristics.

The study also differs from previous research in that it does not operationalise the use of educational innovations as a binary variable that distinguishes between users and non-users. Rather, the definition of several typical user styles addressed the reality that teachers use innovations in different ways. Investigating the relationships between typical user styles, motivational factors, dissemination activities and institutional characteristics provides initial insights into what can stimulate teachers in higher education to engage with educational innovations.

In response to the first research question, the analysis revealed that intrinsic motivation is a strong determinant of teachers’ commitment to educational innovation. In particular, the importance teachers attach to self-enhancement is a very strong motivator. Their wish to try new educational practices and improve their teaching skills are strong drivers. Extrinsic motivation, i.e., the provision of incentives or the expectations of peers and students, does not seem to have this stimulating effect. These finding corroborate those of previous studies investigating teacher motivation in higher education. Stupnisky et al. (2018) have already pointed out that teachers are more likely to innovate when they work in an environment that meets their needs for autonomy. The study by Wilkesmann and Lauer (2020) showed that incentives, as well as New Public Management policy instruments, are not effective when aimed at changing teaching behaviour.

Second, concerning the impact of dissemination in stimulating the use of educational innovations among teachers, the results showed that Adopters were strongly stimulated by the frequency of hearing about specific SFUs, while this was not a significant factor for the Adapters. Thus, only for Adopters, the results of the study are consistent with results of previous research, which showed that targeted dissemination supports the probability of innovation adoption (Khatri, 2018; Southwell et al., 2010; Stanford et al., 2016, 2017). However, in contrast to these studies, our study found that factors such as clear and convincing information, the effort required for implementation, or the need to collaborate with the CEE were only relevant for a small group of teachers. While the other studies were built on a rational actor model in which teachers seek to adopt more effective teaching practices, this study found that the motivational profile of Adopters was significantly different from that of teachers who were assigned to the other adoption styles (see Table 1) and who also perceived innovations as a stimulus to develop their teaching practice.

In response to the third research question, the study revealed that institutional characteristics that aimed at supporting teachers in adopting educational innovations did not have a significant impact. Instead, the individual importance of educational enhancement was found to increase for all typical use types who had already innovated their teaching practice. However, this finding does not indicate that institutional support for educational enhancement is lacking or that respondents had a negative view of these measures. Rather, the results confirm the earlier assumption about the effect of the different forms of motivation. That is, the institutional factors do not sufficiently address the desires and needs underlying teachers' innovative behaviour (Daumiller et al., 2020; Stupnisky et al., 2018).

Discussion

From these answers to the research questions, we would like to draw three conclusions that are relevant for further research and could also support the design of national and institutional initiatives that aim at improving educational activities. The conclusions address the diversity of adoption styles, the function of educational innovations, and the current design of dissemination strategies.

Adoption or Mutation of Innovations?

The study results point out that there is a great deal of diversity in how teachers in higher education use educational innovations. Use of an innovation can rarely be understood as full adoption of the innovation. Rather, we found that a large proportion of the teachers stated that they had made a change in their teaching practice but could not identify whether they had used a specific educational innovation for this, or what source of information was relevant to the design of their change. This finding suggests that the adoption of educational innovations cannot be understood only as a process in which potential users engage with a single innovation that improves their teaching activities. Rather, it shows that teachers’ educational enhancement is a complex process, in which they use very different practices and information. Research on the sustainable use of innovations has also pointed out that innovations are continually adapted and adjusted based on the needs of organisations and teachers (Fagen & Flay, 2009). However, the extent to which innovations are changed differs. Some educational innovations are ‘tolerant’: they can withstand these adaptations and sometimes even become more effective (McKenney, 2014). But there is also the risk of lethal mutations, where the original intention and shape vanishes or becomes replaced by the adaptations (Brown & Campione, 1996, cited in McKenney, 2014). Future research on teachers’ use of educational innovations could therefore pay more attention to teachers’ actual innovation practices and the role of educational innovations.

Innovations as Instruments or Concepts

The results also show that users of educational innovations are stimulated by several factors that do not suggest that teachers are rational actors when changing their teaching. In line with previous studies, the results indicate that intrinsic motivation and high individual importance of improving teaching are strong impulses for dealing with educational innovation in the first place. The nature of these motivations influences which user style is more probable. Adopters have strong intrinsic motivation, i.e. a strong need to try new things and improve their skills. They are also more attracted to dissemination than the other user types. The prospect that the innovation will require a change in their teaching practice is an incentive rather than a barrier for these teachers. The results thus suggest that teachers perceive the function of educational innovations differently. While Adopters may see the innovations as already usable instruments, Adapters and Autonomous Innovators may see them as concepts that inspire their teaching practice. In further research, it would be useful to pay more attention to the question of what function teachers attribute to educational innovations: Do teachers perceive innovations more as instruments to achieve their goals? Or do they perceive innovations more as concepts that inspire them to improve teaching beyond their own goals?

For practitioners implementing initiatives to improve teaching the results could imply that diversifying the support given to teachers could increase their impact. While only a few teachers seem to adopt innovations in their original form, the majority seems to adapt and combine innovative concepts to achieve their learning goals. For these, support that helps them to innovate autonomously could be very helpful.

Innovation in Discourse Communities

Finally, the results also have implications for the development of national and institutional initiatives to improve teaching through the dissemination of educational innovations. Currently, some of these programmes are based on the idea of rational action: that teachers are looking for better ways or innovations with an added value to enhance their teaching practice. These approaches are (implicitly) based on the assumption that educational innovations are definable instruments that provide targeted solutions to teaching challenges, which – also due to their research-based development – can be transferred to different teaching contexts with a manageable number of modifications. Collaboration between the developers of educational innovations and their later users is a supporting factor for the spread of innovations (Khatri, 2018). Against the background of the results of this study, the assumptions of rational actorhood and of innovations as instruments should be revisited when designing dissemination activities. Against the background of the high number of teachers we found in this study who use education innovations as a concept that inspires rather than changes their teaching practice, we would like to suggest creating dissemination approaches that implement discourse communities in which educational innovations serve as concepts (Jenert, 2020). As such they can stimulate the collaboration between members of these communities who will develop and mutate the concept to improve their teaching practice while also benefiting from peer learning. Here, investigating the role of microcultures, their impact on the collaboration in the discourse communities and how they influence other cultures in the institution will be an important area of future research. In addition, these discourse communities could be more responsive to teachers’ needs to try something new while nurturing their values in education.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed for the study are not publicly available as the participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

References

Admiraal, W. (2021). A typology of educators using open educational resources for teaching. International Journal on Studies in Education, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijonse.60.

Andersen Helseth, I., Alveberg, C., Ashwin, P., Braten, H., Duffy, C., Marshall, S., Oftedal, T., & Reece, R. J. (2019). Developing Educational Excellence in Higher Education: Lessons learned from the establishment and evaluation of the Norwegian Centres for Excellence in Education (SFU) initiative. NOKUT, Oslo.

Ashwin, P. (2020). Teaching excellence: Principles for developing effective system-wide approaches. In C. Callender, W. Locke, & S. Marginson (Eds.), Changing higher education for a changing world (pp. 131–143). Bloomsbury Academic.

Ashwin, P. (2022). Developing effective national policy instruments to promote teaching excellence: evidence from the English case. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 6(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2021.1924847

Baas, M., Admiraal, W., & van den Berg, E. (2019). Teachers’ adoption of open educational resources in higher education. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2019(1), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.510

Bajada, C., Kandlbinder, P., & Trayler, R. (2019). A general framework for cultivating innovations in higher education curriculum. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(3), 465–478.

Beaven, T. (2018). ‘Dark reuse’: an empirical study of teachers’ OER engagement. Open Praxis, 10(4), 377. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.4.889.

Daumiller, M., Stupnisky, R., & Janke, S. (2020). Motivation of higher education faculty: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101502

Dee, J. R., & Leisyte, L. (2016). Organisational learning in higher education institutions: Theories, frameworks, and a potential research agenda. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (275–348). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26829-3_6.

Elmore, R. (1996). Getting to scale with good educational practice. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.g73266758j348t33.

Esdar, W., Gorges, J., & Wild, E. (2016). The role of basic need satisfaction for junior academics’ goal conflicts and teaching motivation. Higher Education, 72(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9944-0

Fagen, M. C., & Flay, B. R. (2009). Sustaining a school-based prevention program: Results from the Aban Aya Sustainability Project. Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 36(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198106291376

Harvey, L., & Stensaker, B. (2008). Quality culture: Understandings, boundaries and linkages. European Journal of Educational Research, 43(4), 427–442.

Henke, J., & Dohmen, D. (2012). Wettbewerb durch leistungsorientierte Mittelzuweisungen? Zur Wirksamkeit von Anreiz- und Steuerungssystemen der Bundesländer auf Leistungsparameter der Hochschulen. Die Hochschule: Journal Für Wissenschaft Und Bildung, 21(2), 100–120.

Jenert, T. (2020). Überlegungen auf dem Weg zu einer Theorie lehrbezogenen Wandels an Hochschulen. ZFHE, 15(4), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.3217/ZFHE-15-04/12

Kezar, A. (2011). What is the best way to achieve broader reach of improved practices in higher education? Innovative Higher Education, 36(4), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-011-9174-z

Khatri, R. (2018). A Model for Propagating Educational Innovations in Higher STEM Education: A Grounded Theory Study of Successfully Propagated Innovations [Dissertation]. Western Michigan University. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4233&context=dissertations. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Khatri, R., Henderson, C., Cole, R., Froyd, J. E., Friedrichsen, D., & Stanford, C. (2017). Characteristics of well-propagated teaching innovations in undergraduate STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-017-0056-5

Kottmann, A. (2017). Unravelling tacit knowledge: Engagement strategies of centres for excellence in teaching and learning. In H. Eggins & R. Deem (Eds.), The university as a critical institution? (pp. 217–235). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6351-116-2_12

Kottmann, A. (2023). How centres of excellence in teaching and learning stimulate organisational learning and educational change in higher education institutions. In A. Kottmann, Innovation of education at higher education institutions: The contribution of centres of excellence for teaching and learning (pp. 77–109). University of Twente.

Kottmann, A., Westerheijden, D., & van der Meulen, B. (2020). Learning from Innovations in Higher Education. Enschede. https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/267239563/NOKUT_Final_report_March2020.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2022.

Lašáková, A., Bajzíková, Ľ, & Dedze, I. (2017). Barriers and drivers of innovation in higher education: Case study-based evidence across ten European universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 55, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.06.002

Machado, M. d. L., Soares, V. M., Brites, R., Ferreira, J. B., & Gouveia, O. M. R. (2011). A look to academics job satisfaction and motivation in Portuguese higher education institutions. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1715–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.417.

McKenney, S. (2014). As early as possible. In European agency for special needs and inclusive education (Ed.), Inclusive education in Europe: Putting theory into practice (pp. 25–38). European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

McKenney, S. E., & Reeves, T. C. (2017). Conducting educational design research (Second edition). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Millard, L., & Hargreaves, J. (2015). Creatively employing funding to support innovation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(3), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.760775

Nascimbeni, F., & Burgos, D. (2019). Unveiling the relationship between the use of open educational resources and the adoption of open teaching practices in higher education. Sustainability, 11(20), 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205637

Norsk Senter for Forskningsdata. (2020). Nøkkeltall for universiteter og statlige høyskoler 2020: Database for statistikk om hogre utdanning (DBH). Bergen. Norsk Senter for Forskningsdata. dbh.nsd.uib.no.

NOKUT. (n.d.). Standards and Guidelines for Centres and Criteria for the Assessment of Applications. http://www.nokut.no/Documents/NOKUT/Artikkelbibliotek/UA-enhet/SFU/SFU_Standards_Guidelines_and_Criteria_for_the_Assessment_of_Applications.pdf

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gbv/detail.action?docID=4935198

Roxa, T., & Martensson, K. (2008). Strategic educational development: A national Swedish initiative to support change in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 27(2), 155–168.

Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2013). Understanding strong academic microcultures: An exploratory study. Centre for Educational Development (CED), Lunds universitet.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schuwer, R., & Janssen, B. (2018). Adoption of sharing and reuse of open resources by educators in higher education institutions in the Netherlands: A qualitative research of practices, motives, and conditions. International Review of Researcher in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(3), 151–171.

Smith, K. (2012). Lessons learnt from literature on the diffusion of innovative learning and teaching practices in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.677599

Southwell, D., Gannaway, D., Orrell, J., Chalmers, D., & Abraham, C. (2010). Strategies for effective dissemination of the outcomes of teaching and learning projects. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800903440550

Stanford, C., Cole, R [Renée], Froyd, J., Friedrichsen, D., Khatri, R., & Henderson, C. (2016). Supporting sustained adoption of education innovations: The Designing for Sustained Adoption Assessment Instrument. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-016-0034-3.

Stanford, C., Cole, R [Renee], Froyd, J., Henderson, C., Friedrichsen, D., & Khatri, R. (2017). Analysis of propagation plans in NSF-Funded Education Development Projects. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 26(4), 418–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-017-9689-x.

Stasewitsch, E., Dokuka, S., & Kauffeld, S. (2021). Promoting educational innovations and change through networks between higher education teachers. Tertiary Education and Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-021-09086-0.

Stupnisky, R. H., BrckaLorenz, A., Yuhas, B., & Guay, F. (2018). Faculty members’ motivation for teaching and best practices: Testing a model based on self-determination theory across institution types. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.01.004

Scott, S., & McGuire, J. (2017). Using diffusion of innovation theory to promote universally designed college instruction. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(1), 119–128. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1135837.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

Trowler, P. (2020). Accomplishing change in teaching and learning regimes: Higher education and the practice sensibility (First edition). Oxford University Press.

Warford, M. K. (2017). Educational innovation diffusion: Confronting complexities. In A. M. Sidorkin & M. K. Warford (Eds.), Reforms and innovation in education (Vol. 25, pp. 11–36). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60246-2_2.

Wilkesmann, U., & Lauer, S. (2020). The influence of teaching motivation and New Public Management on academic teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1539960

Wilkesmann, U., & Schmid, C. J. (2012). The impacts of new governance on teaching at German universities. Findings from a national survey. Higher Education, 63(1), 33–52.

Warford, M. K. (2010). Testing a Diffusion of Innovations in Education Model (DIEM). The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 10(3), Article 7, 1–28. https://www.innovation.cc/peer-reviewed/2005_10_3_7_warford_test-diffusion.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2021.

Funding

This study was partially funded by NOKUT, the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Andrea Kottmann. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Andrea Kottmann and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kottmann, A., Schildkamp, K. & van der Meulen, B. Determinants of the Innovation Behaviour of Teachers in Higher Education. Innov High Educ 49, 397–418 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09689-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09689-y