Abstract

Differences between academic disciplines have been a well-studied theme in higher education research. But even though students’ subjective study values are a key factor for successful studying, research examining their disciplinary differences in the higher education context is lacking. To address this, this study draws on expectancy-value theory, investigates students’ subjective study values across nine different disciplines, and analyses its discipline-specific relation to study success. For this, we used a large-scale data sample of N = 6.321 university students from the German National Educational Panel Study. Subjective study values were assessed in terms of intrinsic values, utility values, attainment values, and costs, while study success was captured by students’ grade and dropout intention. Data were analysed through multi-group structural equation modelling. Our findings suggest that (1) students’ subjective study values differ markedly across academic disciplines and (2) study disciplines moderate the relation between study values and study success. On a research level, our findings contribute to a more differentiated view on subjective study values in the higher education context. On a practical level, our findings can help to uncover motivational problems of students from different disciplines, which might ultimately help to reduce dropouts and improve grades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subjective study values are a vital part of successful studying and among the most proximal predictors of academic achievement, effort, and choice (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). Students who value their studies less than their fellow students dropped out of university more often (Schiefele et al., 2007; Schnettler et al., 2020), while students who attribute a high value to their studies are more likely to succeed in their field of study (Part et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Just before entering higher education, students indicate moderate to high study values, but these positive perceptions tends to gradually decline over time (Kosovich et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2019; Schnettler et al., 2020). At some point in their studies, almost all students have asked themselves, “why am I learning this!?” (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2021). The answer to this question shapes study trajectories across all disciplines—but research examining disciplinary differences in students’ study values is lacking. Given the multitude of already established differences in associated domains (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019; Schubarth et al., 2014), disciplinary differences in study values seem just as likely. Law and humanities students, for instance, might place different values on the career-related utility of their studies. To address this gap, we investigate subjective study values across nine groups of study disciplines and analyse its discipline-specific relation to study success using a large-scale data sample of higher education students in Germany.

Expectancy-value theory and associated empirical evidence

Expectancy-value theory (EVT) as proposed by Eccles et al. (1983) is a well-established framework often used to explore higher education students’ motivation and academic achievement (Part et al., 2020; Robinson et al., 2019; Schnettler et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). It posits that the subjective values and expectancies associated with a given task (in our case studying) are key predictors of achievement, effort, and choice—and decades of empirical research have supported these propositions.

According to EVT, subjective study valuesFootnote 1 are seen as a multidimensional construct including four theoretically distinct components (Eccles et al., 1983): intrinsic values, attainment values, utility values, and costs. Intrinsic values refer to students’ interest in their studies and the enjoyment they feel when studying. Utility values refer to the utility that studying has for the individual’s present or future plans (e.g. their studies lead to a respected, stable, or well-payed job). Attainment values address students’ personal value of doing well in their studies and are related to the importance of studying for one’s identity. Lastly, costs reference the negative consequences that are associated with studying (e.g. opportunity cost or effort). Following EVT, intrinsic, utility, and attainment values are thought to be positively associated with study success, while costs are thought to be negatively related to it.

On a theoretical level, study values have long been considered a multidimensional construct, but prior empirical research has often combined the different value dimensions into a single scale (Schnettler et al., 2020). Only recently, empirical studies have indicated that specific value dimensions show unique patterns of relations to educational outcomes (Robinson et al., 2019): In a longitudinal study on German undergraduate students of math and law, intrinsic values, attainment values, and cost, but not utility values, were related to students’ dropout intention (Schnettler et al., 2020). Research on Chinese engineering students indicates that intrinsic values, utility values, and cost, but not attainment values, were associated with dropout intention (Wu et al., 2020). In a study of American undergraduate life science students (using a bifactor model distinguishing between general and specific task values), general subjective study values and cost positively predicted achievement, while utility values negatively predicted achievement (Part et al., 2020). All in all, these results highlight how important it is to take the multidimensionality of study values into account and indicate that value dimensions differ in their contribution to academic outcomes.

To address this, we capture the multidimensional nature of study values and investigate discipline-specific differences in study values and their relation to study success across all four value dimensions. Findings provide new insights into the relative importance of each value dimension for predicting study success across disciplines in higher education, a setting that is unique in regard to the development of study values and their relations to educational outcomes.

Differences across study disciplines

Differences between academic disciplines have been a recurring theme in higher education research (Kuteeva & Airey, 2014; Ylijoki, 2000). A large body of research has shown that university students are no homogeneous group and that study disciplines differ from each other in various aspects (Ylijoki, 2000). At first sight, they vary in terms of their curriculum, their contents, and the knowledge they provide to their students. For example, a major in economics provides students with a deep understanding of economic principles (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019), and a major in medicine provides expertise about the human body, while humanities are associated with good language and communication skills (Briedis et al., 2008). Furthermore, empirical research has indicated that academic disciplines differ in regard to their labour market outcomes (Davies et al., 2013; Porter & Umbach, 2006), workload (Metzger & Schulmeister, 2011, 2020), vocational orientation (Schubarth et al., 2014), teaching and learning practices (Neumann, 2001), or the prospects they provide to their graduates (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019).

Strikingly, disciplinary differences in study values have been largely overlooked. Prior research has primarily addressed study values using pooled data across different disciplines (e.g. Schiefele et al., 2007; Schnettler et al., 2020) or analysed the values of a single discipline (e.g. Robinson et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020).

Vocational orientation and disciplinary differences in study values

We start our investigation of disciplinary differences across study values by looking at their vocational orientation as one of the more apparent connections. Prior research in the German higher education context has outlined three different types of disciplines: profession-oriented disciplines, in which the degree is seen as a prerequisite to practice the professions (e.g. medicine, law), disciplines that qualify for different but clearly describable professions (e.g. natural science, engineering), and scientifically-oriented degree programmes without a concrete occupational reference (e.g. humanities and social sciences) (Schubarth et al., 2014).

Profession-orientated disciplines are by definition closely linked to specific economic sectors and prepare students for rather specific jobs (Schubarth et al., 2014). This, in combination with the fact that the associated academic degree is often a prerequisite to practice in one’s desired profession, suggests that profession-orientated disciplines are associated with a high utility value. On the other end of the spectrum, scientifically-orientated disciplines are not as clearly associated with a job or economic sector (Schubarth et al., 2014). Students of these disciplines might have lower utility values, but rather study because they perceive their studies as interesting and fun (i.e. higher intrinsic values). These theoretical linkages are also supported by empirical studies on major choice in Germany, which indicate that when compared to other disciplines, humanities students place less value on career-related aspects of their studies (e.g. high income, secure position), whereas personal development and interesting studies are particularly important to them (Briedis et al., 2008). Similarly, students enrolled in economics reported stronger career-related values and weaker intrinsic values than students enrolled in social sciences (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019).

Additional factors associated with disciplinary differences in study values

To outline further discipline-specific differences in study values, we look at research on salaries, goal orientation, and the workloads of disciplines. First, prior research in Germany, the UK, and the US has indicated that majors differ in terms of future salary (Briedis et al., 2008; Davies et al., 2013; Porter & Umbach, 2006). In particular the discipline groups medicine, mathematics, and computing as well as law and economics were associated with high graduate premiums, while humanities students, on average, earn less than students of other disciplines (Briedis et al., 2008; Davies et al., 2013). As wage and job-stability reflect important facets of utility value, disciplines associated with these aspects should attract students who place higher values on the career-related utility of their studies.

Second, research on students’ goal orientation indicates that disciplines that are associated with highly competitive labour markets might feel a stronger need to display their competence through good grades (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019). This in turn should be associated with higher attainment values for disciplines like STEM or economics, as they qualify for many different but clearly describable professions. Empirical research in India supports this idea, indicating that science students place higher values on doing well in class than students of social sciences, humanities (Upadyay & Tiwari, 2009), and arts faculties (Shekhar & Devi, 2012).

Third, research on students’ workload in Germany indicates that even with the introduction of the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS), students’ average workload differs across study disciplines (Metzger & Schulmeister, 2011). Specifically, social sciences and humanities tend to have a lower workload than economics and STEM disciplines (Metzger & Schulmeister, 2020). A similar picture might exist for (opportunity) costs, and students of social sciences and humanities might associate their studies with less strain and sacrifice than other disciplines.

All in all, there are both theoretical and empirical reasons for differences in students’ study values. Research on this subject can contribute to the field of higher education in a variety of different ways: First, it could help to uncover motivational problems of specific disciplines—humanities students, for example, might feel like their studies have little value for their future jobs. This information could then be used by counselling services who might organise events where potential career paths in the humanities are outlined (e.g. career-days, alumni talks). Instead of seeing low values as a deficit on the side of the students, it could also be seen as structural differences between disciplines, making it important to provide each with the right environment to succeed. Second, it could enrich future intervention approaches aimed to foster students’ study values and motivation. For example, disciplines that show lower utility values might gain additional benefits from utility value interventions often discussed in prior research (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2021). Third, our study can provide valuable information for student counselling services: As a good fit between the values of the students and their study environment is vital for successful studying (Bohndick et al., 2018), information on the value profiles of disciplines can lead to more informed major choices. Students with high utility and attainment values might therefore be better off studying economics than humanities. In the same vein, it can help guide students who are uncertain whether they should choose a discipline they are particularly interested in or rather choose a major that provides the highest value for their future (career) plans.

The influence of study disciplines on the relation between subjective study values and study success

Student success and learning are central goals of higher education institutions (Bohndick et al., 2018), but around one-third of all students in Germany drop out of their major without a degree (Messerer et al., 2023). As this results in high costs for individuals, institutions, and society, it is vital to analyse and understand the determinants of study success (Bohndick et al., 2018; Messerer et al., 2023). When investigating study success, researchers have addressed a wide range of facets, including grades (Bohndick et al., 2018), dropout (Schnettler et al., 2020), satisfaction (Kegel et al., 2021), and skill development (Badcock et al., 2010). In this study, we focus on students’ dropout intention (i.e. the conscious intention to leave their academic discipline before completion) and current grade point average (i.e. the score assigned to their academic performance, reflecting their understanding and knowledge of the content).

Prior research has often highlighted the central role that subjective study values play in academic success, suggesting, for example, that students with higher study values were less likely to drop out of university (Schiefele et al., 2007; Schnettler et al., 2020). In light of the disciplinary differences in students’ study values outlined above, it seems likely that the relationship between the study values and study success also depends on the discipline under consideration—which might help to establish the connection more clearly and with more differentiation. In profession-orientated disciplines like medicine, law, or teaching, the study degree in itself is of huge value, because it is seen as a prerequisite to practice the aspired profession. The value students associate with their studies might therefore lie more in the degree and less in the study itself. For students of these disciplines, low study values (e.g. little interest in the content) might be less detrimental to their persistence and success, as the importance of the degree can offset problems associated with low study values. Consequentially, profession-orientated study disciplines would show a weaker association between study values and study success than other disciplines. A degree in humanities or social sciences, on the other hand, is not associated with a particular job (Schubarth et al., 2014) and, at least in Germany, is surrounded by various clichés and often seen as less valuable (Briedis et al., 2008). If the degree is associated with little value, the value of these disciplines will likely lie in the study itself (because students find it interesting or important). As a result, students in disciplines with little vocational orientation should show a strong relation between study values and study success.

While empirical evidence on this is missing, Heublein et al. (2017) indicate that for Germany, study motivation is of higher importance for dropout from humanities than it is for STEM or law. As EVT postulates subjective study values as a critical component of study motivation, similar patterns for the relationship between the study values and study success can be expected. In light of the disciplinary differences and theoretical considerations outline above, this should correspond to a weaker relation between study values and study success for profession-orientated disciplines, while scientifically-orientated disciplines should show a stronger relation between study values and study success.

The present study

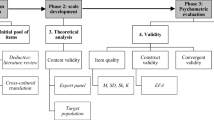

With reference to the above, the present study investigates disciplinary differences in subjective study values and analyses the relation between study values and study success across disciplines. We capture the multidimensional nature of study values following the conceptualisation of Eccles et al. (1983) and investigate the conceptual model summarised in Fig. 1. This model is analysed across nine different study disciplines using structural equation modelling with a large-scale data sample of higher education students in Germany. Our research is guided by the following two questions:

-

(1)

Do students’ subjective study values differ between academic disciplines?

We assume that students’ subjective study values depend on their academic discipline and expect differences in line with the research described above.

-

(2)

What is the relationship between subjective study values, dropout intention, and grades for different study disciplines?

We hypothesise that study disciplines moderate the relationship between students’ study values, dropout intention, and grades. The connection between study values and study success should depend on the discipline under consideration

Methodology

Sample and procedure

This paper uses secondary data from the first-year student cohort (SC5) of the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (Blossfeld & Rossbach, 2019; NEPS Network, 2021). The NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) in cooperation with a nationwide network and collects longitudinal data on educational processes and competence development in Germany. The NEPS started surveying first-year students in the winter term 2010/11 and thereafter followed this cohort during the course of their studies. In this study, we included all participants with complete datasets in our variables of interest, resulting in a sample N = 6.321 university students. Demographic characteristics of our sample can be found in Table 1.

Research setting

This study is set in the German higher education context. As we investigate how study values differ between academic disciplines, additional contextual information on these disciplines are required to make judgements about what findings may be context-bound and what may have general implications. Most students in Germany enter higher education after 12 or 13 years of school (depending on the state), using the Abitur as a general higher education entrance qualification (Hüther & Krücken, 2018). They can then choose between over 20,000 degree programmes and around 400 state recognised universities (Hochschulrektorenkonferenz, 2021). Over 90 percent of students study at public universities that are almost completely free of charge (Hüther & Krücken, 2018). Most study programmes (e.g. humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, economics) consist of a three years bachelor’s, followed by a two years master’s degree programme. A few other disciplines, most notably law and medicine, lead up to a state-organised exam (Staatsexamen) deciding the final results of the students. Some of these disciplines have restricted admissions and require a certain grade (or higher) to qualify for entrance; medicine and psychology, for example, require a near perfect (1.0) abitur grade.

Measures

The NEPS collects data using established scales from the literature which we use to measure subjective study values and study success (LIfBi, 2022; Schiefele et al., 2002; Trautwein et al., 2007). Measures used to control for various covariates can be found in the supplementary information.

Subjective study values

Based on the EVT, we assessed students’ intrinsic value (four items, e.g. “because I am very interested in the contents of my studies”, α = 0.85), utility value (four items, e.g. “to be able to pursue a well-paid profession later on”, α = 0.79), attainment value (four items, e.g. “being successful at my studies is important to me”, α = 0.70), and cost (one item, “for my studies I have to give up things that are very important to me [e.g. existing social contacts, economic independence]”). All four value dimensions were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not true at all” (1) to “totally true” (4) (LIfBi, 2022; Schiefele et al., 2002).

Study success

Study success was measured in terms of students’ dropout intention (subjective measure) and grades (objective measure). Students’ dropout intention was measured using three items (e.g. “I seriously consider to give up studying altogether”, α = 0.71) on a 5-point Likert scale (LIfBi, 2022; Trautwein et al., 2007). Grades were assessed as the current, self-reported grade point average in the respective study discipline. For most disciplines, grades raged from 1.0 (highest) to 5.0 (lowest). Law students use a point system, which we adjusted to match the normal grade system (University of Bremen, 2017).

Study disciplines

Study disciplines were divided into the following nine discipline groups typically used in the German higher education context: (1) social sciences (n = 557), (2) law (n = 178), (3) economics (n = 797), (4) sport, linguistic, and cultural studies (n = 1846), (5) mathematics and natural sciences (n = 1441), (6) medicine and health sciences (n = 329), (7) engineering (n = 893), (8) art and art science (n = 164), and (9) veterinary medicine, agricultural, forestry, and nutritional sciences (n = 145) (Destatis, 2010; LIfBi, 2022).

Analytical procedure

To investigate our research questions, we conducted multi-group structural equation analysis with a maximum likelihood estimator, using the package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) in R (R Core Team, 2023). Following our conceptual framework, the structural equation model (SEM) included students’ intrinsic values, utility values, attainment values, costs (variables of interest), expectations, gender, socio-economic status, and first-generation status (covariates) as exogenous and dropout intention and grades as endogenous variables. Regarding research question one, we analysed standardised latent mean differences in subjective study values comparing each of the nine disciplines. Regarding research question two, we investigated the moderating effect of study disciplines and analysed the disciplines specific relationship between study values and study success using standardised regression coefficients.

As a non-negligible number of students have missing values in grades, we include a detailed breakdown of missing values, their underlying mechanisms, and their effect on subjective study values in our supplementary information. Furthermore, descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and intercorrelation between the scales, can also be found in the supplementary information.

Measurement invariance across study disciplines

Measurement invariance indicates that the measurement properties of a scale are equal across groups or contexts (Luong & Flake, 2021) and is required for cross-group comparisons (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Following a common classification of invariance types (Schmitt & Kuljanin, 2008; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000), a series of nested models with increasing constraints were compared. In model 1, configural invariance with no invariance constraints was examined. Weak invariance where factor loadings were restricted across disciplines was tested in model 2. Strong invariance with restricted loadings and intercepts across disciplines was investigated in model 3. Last, model 4 examined strict invariance with restricted loadings, intercepts, and residuals across groups. If additional invariance constraints result in little change in the goodness of fit, this is viewed as support for invariance. To test for invariance, we use guidelines of prior research, indicating that changes of < 0.010 in CFI and < 0.015 in RMSEA are acceptable (Chen, 2007).

The comparison of the nested models indicated that for our SEM, weak measurement invariance, but not strong (and strict) measurement invariance, was supported. To cope with this, partial invariance was established. Under partial invariance, the model is examined to systematically identify the most non-invariant item intercepts. Afterwards, a new model is specified in which these parameters are estimated freely across groups (Luong & Flake, 2021). Following the iterative process of Beaujean (2014) and Luong and Flake (2021), we examined the modification indices of model 3 (restricted loadings and intercepts) freed the non-invariant item intercepts associated with the greatest model fit improvement, compared the new model to model 2, and repeated the process until partial strong invariance was achieved. In this process, we freed the intercepts for two items of utility value (“to be able to live a financially secure life” and “to be able to pursue a well-paid profession”). After freeing the intercepts for both items, our model lends support to (partial) strong and strict invariance and can be used for cross-group comparison. Additional information regarding the invariance testing can be found in the supplementary information.

Results

Differences in latent means

To examine our first research question, we calculated standardised latent mean differences, comparing the subjective study values of each of the nine disciplines. For this, loadings and manifest intercepts of the SEM were restricted to be the same across the groups. Latent intercepts of the second group can then be interpreted as effect sizes that assess the deviation to the first group. The model showed a decent fit with the data (χ2 (1645) = 4503.518, CFI = 0.917, RMSEA = 0.050 (CI: 0.048–0.051), SRMR = 0.049). Standardised latent mean differences are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

We found various differences in the latent means of study disciplines. Art students had higher intrinsic values than students of all other disciplines, while economic students showed the lowest intrinsic values. Medicine students reported high intrinsic values, scoring only lower than art students. Law students had higher utility values than all their peers in other disciplines and were closely followed by economics students (higher than students of all disciplines except law and veterinary medicine, where no significant effects were found). Medicine students had lower utility value than students of all other disciplines. Law students reported higher attainment values than students of all other disciplines, while sport, linguistic, and cultural studies showed higher attainment values than social sciences, mathematics and natural sciences, engineering, and medicine. Medicine had particularly high costs (higher than all disciplines except veterinary medicine, where no significant effect was found), while social science students reported relatively low costs (lower than students of all disciplines except sports, linguistic and cultural studies, and law, for which no significant effects were found).

Associations with study success and the moderating effect of study disciplines

Regarding research question two, the moderating effect of study disciplines was analysed by comparing two SEMs—one model with and one model without restricted regression paths across the groups. We found a significant difference between the two models (\(\Delta\) χ2 (160) = 529.77, p < 0.001), indicating that the relationship between subjective study values and study success differs between study disciplines. To further analyse these differences, the multi-group SEM was investigated and results of the standardised regression coefficients are presented in Table 4.

Our results indicate that for all disciplines except law, veterinary medicine, and arts, intrinsic values were negatively related to students’ dropout intention. Utility values, on the other hand, had no significant association with dropout intention across all disciplines except engineering. Attainment values had a negative association for the three discipline groups sport, linguistic, and cultural studies, mathematics and natural sciences, and economics, but no significant association with the remaining disciplines. For costs, most disciplines showed a positive association with dropout intention, while arts showed no association and veterinary medicine showed a negative association. In general, standardised regression coefficients for dropout intention were small to moderate (between 0.072 and 0.257) in size and relatively similar across disciplines and value dimensions.

Our results for grades indicate no association to intrinsic values across all disciplines, but a significantly positive association to utility values for all disciplines except arts. Attainment values had a negative relation to grades for all disciplines but arts and law, while cost had a positive association for medicine, but no association for the other disciplines. Standardised correlation coefficients for grades showed a strong deviation across disciplines and ranged from small to large in size (between 0.184 and 0.640).

Discussion

In this article, we investigate subjective study values across nine different disciplines and analyse the discipline-specific relation to grades and dropout intention. Building on EVT, data of N = 6.321 higher education students from the German National Educational Panel Study were analysed using a structural equation modelling approach. Our findings suggest that (1) students’ subjective study values differ markedly across academic disciplines and (2) study disciplines moderate the relation between study values and study success. All in all, our findings contribute to a more differentiated understanding of study values in the higher education context. Going forward, research could consider multiple disciplines, value dimensions, and subsequent outcomes to generate a more complete understanding of students’ subjective study values. On a practical level, our findings can help to uncover motivational problems of students from different disciplines, which might ultimately help to reduce dropouts and improve grades.

Students’ subjective study values differ across academic disciplines

For our first research question, we investigated if students’ subjective study values differed from the study values of their peers in other disciplines. In line with our general assumption, we find large differences in latent means, indicating various disciplinary differences.

Disciplinary differences seemed to be systematic, and interesting patterns along the vocational orientation of the disciplines emerged. For example, economics, law, and engineering students as more profession-orientated disciplines generally reported much higher utility values, but were less intrinsically motivated than their peers in other disciplines. On the other hand, students of social sciences and arts, as scientifically-orientated disciplines, were more intrinsically motivated but showed lower utility values than students from most other disciplines. This is in line with prior research from Germany, indicating that students enrolled in economics report stronger extrinsic and weaker intrinsic aspirations than students enrolled in social sciences (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019) and that students of humanities and social sciences are less extrinsically and more intrinsically motivated than their peers (Briedis et al., 2008). Furthermore, students of profession-oriented disciplines (namely, law and economics) reported higher attainment values, whereas students of scientifically-oriented disciplines (namely, social and cultural sciences) reported lower costs than students in most other disciplines.

Against our initial expectations, medicine does not follow the above-described patterns of other profession-orientated disciplines. Even though medicine is closely linked to a stable and well-paying career and the major is considered a prerequisite to practice the profession, medicine students showed lower utility values than students of all other disciplines. They also associate lower attainment values and higher costs with their studies but are much more intrinsically motivated than their peers in other disciplines. The value profile of medicine students stands in contrast to other profession-oriented disciplines and instead is similar to students of scientifically-orientated disciplines like arts and social science. Medicine students might favour interest, altruistic values, and the desire to help people, rather than monetary rewards or the status associated with being a doctor. Strict admission restrictions in Germany might also play a part in this, as interest in the discipline might have started early during school time and is therefore much more stable. Further research with an explicit focus on the value profile of medicine students and their development throughout their studies could be worthwhile.

All in all, our results indicate that study values differ across disciplines. Disciplinary differences in study values can have important practical implications and can help higher education institutions to better understand the study values of their students and address associated problems of their respective study discipline. In particular, low study values might have widespread consequences as they are closely associated with study motivation and a key predictor for study success (Eccles et al., 1983; Schnettler et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Our study indicates that students of social sciences and medicine in particular feel like their studies have less value for their future jobs. To address this, lecturers could more explicitly emphasise the professional relevance of their contents and further highlight the skills acquired during the studies. One option could be a utility value intervention, a classroom-based assignment that helps students to make connections between the content of their studies and their (personal and professional) lives (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2021). Given their lower utility values, social sciences and medicine could particularly benefit from them and further research investigating the effectiveness of these interventions for specific disciplines could be worthwhile. Furthermore, our results indicate that economics students feel like their study is less interesting and fun than students of all other disciplines do. As prior studies indicate that intrinsic values are of particular importance for study success (Rump et al., 2017), higher education institutions should carefully consider ways to address these problems and try to foster economics students’ intrinsic values. Engineering and medicine were associated with both higher costs and lower attainment values than many other disciplines. This could point towards particularly high demands in these disciplines. Students might have to invest all their time and energy into their studies, and as a result, no longer value attaining good grades and instead aim to simply pass the exam.

It has to be noted that studying in a public university in Germany is almost completely free of charge. High tuition fees, common in the US or UK, could drastically change the values students place on their studies and results regarding disciplinary differences might not be transferrable in such cases. In these environments, students might favour job-related utility or attaining good grades over interest.

Study disciplines moderate the relation between study values and study success

For our second research question, we investigated the relationship between study values and study success across nine different disciplines. In line with our assumptions, we find that study disciplines moderate this relationship, both in terms of magnitude and significance. In regard to grades and dropout intention, students of different disciplines benefit from different study values. Results of this study extend existing research by establishing disciplinary differences in the relation between study values and study success.

Especially the relationship between attainment values and study success was influenced by the discipline under consideration. For example, law showed no association between attainment values and both measures of study success, while various other disciplines (e.g. cultural studies, economics, or natural sciences) did. This is in line with our initial assumptions and might indicate that low study values could be less detrimental to law students’ success, as the major itself is of high values for their future life and career-path and can offset problems associated with low study values. Again, this assumption does not hold true for medicine, which showed a particularly strong positive association between attainment values and grades and was one of the few disciplines where cost influenced both dropout intention and grades. In light of the high costs and low attainment values that students associated with medicine, their negative influence on both grades and retention might be a point of concern for higher education institutions. Future research incorporating additional facets of costs (e.g. effort and psychological cost) would be worthwhile in this context and could help to better differentiate the relationship between costs and study success for medicine students.

Interestingly, both intrinsic and utility values were mostly stable across disciplines, but clear patterns across the two measures of study success emerged. For most disciplines, intrinsic values were negatively associated with dropout intention but showed no association with grades. Utility values on the other hand showed no association to dropout intention and a positive relationship to grades (across all disciplines but arts). Various previous studies highlight the positive effect that intrinsic values have on study success (Janke & Dickhäuser, 2019; Rump et al., 2017; Schnettler et al., 2020), even arguing that it is particularly important to create study conditions that promote students’ intrinsic values (Rump et al., 2017). While our study indicates that intrinsic values can be an important resource for students at the verge of dropping out, the current and a few other empirical studies have found that higher intrinsic values do not lead to better grades (Part et al., 2020; Schnettler et al., 2022).

Even though utility values are often targeted in interventions and training sessions (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2021; Schnettler et al., 2020), no association between utility values and dropout intention was found for all disciplines except engineering. In all disciplines except arts, higher utility values were even associated with worse grades. In light of the numerous randomised field trials that have linked utility value interventions to an increase in course-specific performance or persistence in a major (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2021), these results are surprising. They find, however, some support in empirical studies (Part et al., 2020; Schnettler et al., 2022). Prior research has hypothesised that utility values are less explicit in students’ perceptions and as a result could be more of a distant goal that students associate less with present academic outcomes (Kosovich et al., 2017). Future research should investigate inconsistent findings regarding the association between utility values, utility value interventions, and study success.

Our study was the first to investigate study values and analyse the discipline-specific relation to study success in a wider framework, addressing the multidimensional nature of study values, incorporating different study disciplines, and capturing both objective and subjective measures of study success. In line with previous studies, our findings provide support for the multidimensional nature of study values and highlight the unique contribution of specific value dimensions (Gaspard et al., 2017; Schnettler et al., 2020). Additionally, we find that students’ subjective study values differ across academic disciplines and extend existing research by establishing disciplinary differences in the relationship between study values and study success, especially regarding attainment values. The relationship between study values and study success seems to be more nuanced than previous studies indicate, and our study can contribute toward a better understanding in the higher education context. As we focus on a rather narrow and achievement-oriented understanding of study success (i.e. in terms of grades and dropout intention), future studies would benefit from additional learning-oriented outcomes (e.g. competency development). This could paint a broader picture of study values and might help us understand which value dimensions should be pursued in a meaningful way. Our results regarding grades and dropout suggest that no study value can do it all (i.e. is related to grades and dropout across every discipline). Policies and counselling should consider the entire bandwidth of study values, as different value dimensions are important for different disciplines and different facets of study success.

Limitations and further research

To draw valid conclusions from our results, our instruments had to reflect strong measurement invariance across academic disciplines. Many earlier studies ignored this requirement, while others had difficulty establishing measurement invariance across academic disciplines (Gaspard et al., 2017). Even though we overcame these problems by establishing partial strict measurement invariance, our results regarding utility values and study success (especially the moderating effect of disciplines) might be biased by the two invariant items.

In our study, we use data from the NEPS, which comes with a variety of advantages, especially the large and representative sample of students, that allowed us to investigate a complex model across nine disciplines incorporating four different value dimensions and two measures of study success. However, we could only use one-item measures for costs and grades. This can limit their reliability and might have influenced the power and significance of our results. Future studies could address this shortcoming and use more extensive and reliable scales. Studies that include not only opportunity costs but also emotional costs and effort (Schnettler et al., 2020) would be worthwhile.

When responding to rating scale items, people use their own subjective judgement to select a category that best describes their situation (Wang et al., 2006). These subjective judgements involve a certain level of heterogeneity and randomness. Because SEMs do not consider this heterogeneity, they may be too stringent and can lead to biased estimates or inflated test-reliability (Wang et al., 2006). Future research would benefit from methods that account for randomness in subjective judgement and could use, for example, the random-effects rating scale model (RE-RSM; Wang et al., 2006).

Even though the NEPS assesses students in waves, our variables of interest were only collected during one point in time. As a result, findings of our study can only be interpreted cross-sectionally. Further longitudinal studies could clarify not only the correlation, but also the causation underlying the effects found in our study. In light of our results, future research could also investigate if the development of study values over the course of the semester (or the whole major) differs across study disciplines. Disciplines with higher utility values might be associated with a slower decline in study values, as their motivation is associated with a long-term goal and thought to be more stable (Schnettler et al., 2020).

As the relationship between subjective study values, dropout intention, and grades was investigated across nine different disciplines and had a rather small explanatory power, we want to caution against an overinterpretation of the individual associations (e.g. the negative association between intrinsic values and dropout intention for engineering students). Instead, the focus should lie on the systematic patterns and more general implications of our results. Further studies could put a greater emphasis on the associations for each discipline and thus might provide support for our more detailed evidence.

Despite these limitations, this study makes a number of important contributions to existing research. Most importantly, we contribute to a more differentiated view on study values and provide future research with a better understanding of study values in the higher education context. More specifically, we find that study values differ across academic disciplines and that study disciplines moderate the relation between study values and study success. On a practical level, our findings can help to uncover motivational problems of students from specific disciplines: economics students, for example, feel like their studies are not particularly interesting or fun and show the lowest intrinsic values out of all disciplines. More generally, most profession-orientated disciplines reported higher utility and attainment values, but were less intrinsically motivated than other disciplines. On the other hand, students of social sciences and arts, as scientifically-orientated disciplines, were more intrinsically motivated and showed lower costs, but also had lower utility values than many of their peers in other disciplines. Further research is needed to replicate our results and to investigate why and how these differences arise.

Notes

Prior research on EVT has been inconsistent in its terminology and has often used the terms subjective task values, task values, values, or value beliefs interchangeably (Part et al., 2020). In the higher education context, studies have furthermore used the terms subjective study values, study values, or value of studies (Schnettler et al., 2020). Within this study, we use the terms subjective study values and study values interchangeably and refer to the (subjective) task values associated with studying.

References

Badcock, P. B., Pattison, P. E., & Harris, K. L. (2010). Developing generic skills through university study: A study of arts, science and engineering in Australia. Higher Education, 60, 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9308-8

Beaujean, A. A. (2014). Latent variable modeling using R: A step by step guide. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315869780

Blossfeld, H. P., & Rossbach, H. G. (Eds.). (2019). Education as a Lifelong Process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Edition ZfE (2nd ed.). Springer VS.

Bohndick, C., Rosman, T., Kohlmeyer, S., & Buhl, H. M. (2018). The interplay between subjective abilities and subjective demands and its relationship with academic success. An application of the person–environment fit theory. Higher Education, 75(5), 839–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0173-6

Briedis, K., Fabian, G., Kerst, C., & Schaeper, H. (2008). Berufsverbleib von Geisteswissenschaftlerinnen und Geist4eswissenschaftlern. HIS GmbH.

Chen, F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Davies, P., Mangan, J., Hughes, A., & Slack, K. (2013). Labour market motivation and undergraduates’ choice of degree subject. British Educational Research Journal, 39(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.646239

Destatis. (2010). Bildung und Kultur: Studierende an Hochschulen. Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00006845/2110410117004.pdf

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., & Meece, J. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Gaspard, H., Häfner, I., Parrisius, C., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2017). Assessing task values in five subjects during secondary school: Measurement structure and mean level differences across grade level, gender, and academic subject. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.09.003

Heublein, U., Ebert, J., Hutzsch, C., & Isleib, S. (2017). Zwischen Studienerwartungen und Studienwirklichkeit: Ursachen des Studienabbruchs, beruflicher Verbleib der Studienabbrecherinnen und Studienabbrecher und Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquote an deutschen Hochschulen. Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung GmbH.

Hochschulrektorenkonferenz. (2021). Statistische Daten zu Studienangeboten an Hochschulen in Deutschland. Studiengänge, Studierende, Absolventinnen und Absolventen. Wintersemester 2021/2022. HRK.

Hulleman, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2021). The utility-value intervention. In G. M. Walton & A. J. Crum (Eds.), Handbook of wise interventions: How social psychology can help people change (pp. 100–125). Guilford Press.

Hüther, O., & Krücken, G. (2018). Higher education in Germany: Recent developments in an international perspective (Vol. 49). Springer.

Janke, S., & Dickhäuser, O. (2019). Different major, different goals: University students studying economics differ in life aspirations and achievement goal orientations from social science students. Learning and Individual Differences, 73, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.05.008

Kegel, L. S., Schnettler, T., Scheunemann, A., Bäulke, L., Thies, D. O., Dresel, M., Fries, S. & Leutner, D. (2021). Unterschiedlich motiviert für das Studium: Motivationale Profile von Studierenden und ihre Zusammenhänge mit demografischen Merkmalen, Lernverhalten und Befinden. ZeHf–Zeitschrift für empirische Hochschulforschung, 4(1), 13–14. https://doi.org/10.3224/zehf.v4i1.06

Kosovich, J. J., Flake, J. K., & Hulleman, C. S. (2017). Short-term motivation trajectories: A parallel process model of expectancy-value. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.004

Kuteeva, M., & Airey, J. (2014). Disciplinary differences in the use of English in higher education: Reflections on recent language policy developments. Higher Education, 67(5), 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9660-6

LIfBi. (2022). National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). University of Bamberg. Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.neps-data.de/Datenzentrum/%C3%9Cbersichten-und-Hilfen/NEPSplorer#/search/sc=5&y=-1&cl=226,224,1918,618

Luong, R., & Flake, J. K. (2021). Measurement invariance testing using confirmatory factor analysis and alignment optimization: A tutorial for transparent analysis planning and reporting. Psychological Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/qr32u

Messerer, L. A., Karst, K., & Janke, S. (2023). Choose wisely: Intrinsic motivation for enrollment is associated with ongoing intrinsic learning motivation, study success and dropout. Studies in Higher Education, 48(1), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2121814

Metzger, C., & Schulmeister, R. (2011). Die tatsächliche Workload im Bachelorstudium. Eine empirische Untersuchung durch Zeitbudget-Analysen. In S. Nickel (Hrsg.), Der Bologna-Prozess aus Sicht der Hochschulforschung. Analysen und Impulse für die Praxis (S.68–78). CHE.

Metzger, C., & Schulmeister, R. (2020). Zum Lernverhalten im Bachelorstudium. Zeitbudget-Analysen studentischer Workload im ZEITLast-Projekt. In Studentischer Workload (pp. 233–251). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28931-7_9

NEPS Network. (2021). National educational panel study, scientific use file of starting cohort first-year students. https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC5:15.0.0

Neumann, R. (2001). Disciplinary differences and university teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 26(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070120052071

Part, R., Perera, H. N., Marchand, G. C., & Bernacki, M. (2020). Revisiting the dimensionality of subjective task value: Towards clarification of competing perspectives. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62, 101875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101875

Porter, S. R., & Umbach, P. D. (2006). College major choice: An analysis of person–environment fit. Research in Higher Education, 47(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-9002-3

R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 12 June 2023

Robinson, K. A., Lee, Y., Bovee, E. A., Perez, T., Walton, S. P., Briedis, D., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2019). Motivation in transition: Development and roles of expectancy, task values, and costs in early college engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1081–1102. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000331

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rump, M., Esdar, W., & Wild, E. (2017). Individual differences in the effects of academic motivation on higher education students’ intention to drop out. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(4), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1357481

Schiefele, U., Moschner, B., & Husstegge, R. (2002). Skalenhandbuch SMILE-Projekt. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, Abteilung für Psychologie.

Schiefele, U., Streblow, L., & Brinkmann, J. (2007). Aussteigen oder Durchhalten. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 39(3), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.39.3.127

Schmitt, N., & Kuljanin, G. (2008). Measurement invariance: Review of practice and implications. Human Resource Management Review, 18(4), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.03.003

Schnettler, T., Bobe, J., Scheunemann, A., Fries, S., & Grunschel, C. (2020). Is it still worth it? Applying expectancy-value theory to investigate the intraindividual motivational process of forming intentions to drop out from university. Motivation and Emotion, 44(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09822-w

Schnettler, T., Scheunemann, A., Bäulke, L., Thies, D. O., Kegel, L., Bobe, J., Dresel, M., Fries, S., Leutner, D., Wirth, J., & Grunschel, C. (2022). Dimensionality and dynamics of student motivation from the perspective of situated expectancy-value theory in Higher Education. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Schubarth, W., Speck, Ulbricht, K, Dudziak, J., & Zylla, B. (2014). Employability und Praxisbezüge im wissenschaftlichen Studium. Berlin: Hochschulrektorenkonferenz.

Shekhar, C., & Devi, R. (2012). Achievement motivation across gender and different academic majors. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v2n2p105

Trautwein, U., Jonkmann, K., Gresch, C., Lüdtke, O., Neumann, M., Klusmann, U., & Baumert, J. (2007). Transformation des Sekundarschulsystems und akademische Karrieren (TOSCA). Dokumentation der eingesetzten Items und Skalen, Welle 3. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

University of Bremen. (2017). Notenumrechnung bei der Anerkennung von Prüfungsleistungen durch den Prüfungsausschuss am FB6. Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.uni-bremen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/sites/zpa/pdf/Jura/Hauptstudium/JUR_Staatsexamen_Notenumrechnung_bei_Anerkennung_von_Pruefungsleistungen.pdf

Upadyay, & Tiwari. (2009). Achievement motivation across different academic majors. Indian Journal of Social Science Researches, 6(2), 128–132.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002

Wang, W. C., Wilson, M., & Shih, C. L. (2006). Modeling randomness in judging rating scales with a random-effects rating scale model. Journal of Educational Measurement, 43(4), 335–353.

Wu, F., Fan, W., Arbona, C., & de La Rosa-Pohl, D. (2020). Self-efficacy and subjective task values in relation to choice, effort, persistence, and continuation in engineering: An Expectancy-value theory perspective. European Journal of Engineering Education, 45(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2019.1659231

Ylijoki, O.-H. (2000). Disciplinary cultures and the moral order of studying- A case-study of four Finnish university departments. Higher Education, 39(3), 339–362.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Breetzke, J., Özbagci, D. & Bohndick, C. “Why are we learning this?!” — Investigating students’ subjective study values across different disciplines. High Educ 87, 1489–1507 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01075-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01075-z