Abstract

Companies have highly adopted sustainability reporting practices. Nonetheless, there are still some important research gaps related to the contents that sustainability reports should include and the appropriate frameworks to define them. This research contributes to the study of sustainability reporting practices of companies from a sectorial perspective, and it is focused on applying the materiality principle. It combines a qualitative and a quantitative approach to assess the materiality and the quality of GRI reports among sustainability dimensions and companies within an industry. To this end, an innovative research method based on scores is proposed and applied to a sample of companies in the telecommunications industry. The results indicate that while the GRI sustainability issues declared as material are more likely to be reported, there are still incoherencies in using materiality analysis as a threshold for reporting. Furthermore, there is no evidence that the materiality or quality of the reports differs among companies or sustainability dimensions. The findings suggest that materiality analysis, as companies present it, may lead to incoherencies in treating GRI aspects and indicators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporations periodically disclose their economic performance through their financial statements included in their annual reports or other public documents. However, their activities have more than economic impacts, and diverse stakeholders increasingly demand a more comprehensive disclosure covering social and environmental issues not addressed by traditional financial reports (Dumay et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2017; Salesa et al., 2022). Sustainability issues determine the environment where companies operate and therefore influence the strategies they take and compromise their survival. Even though corporate decision-making is often heavily reliant on financial information, long-term success may rely on aspects related to its social and environmental impacts and performance.

Directive 2014/95/EU requires certain companies to disclose some non-financial reports, depending on their dimension, employees number, and income. Sustainability reports, understood in this research as voluntary reports, integrate information about companies’ performance on the social, environmental, and economic aspects, relevant not only for them and their shareholders but also for the societies where they act (Andrew & Baker, 2020; Escrig-Olmedo et al., 2019). Companies also tend to inform about the policies and actions addressed to mitigate the negative impacts of their activities (Gray et al., 2014). The disclosed information may serve as a proxy to identify the issues corporations consider relevant or material in the definition of their corporate social responsibility strategy. This information helps stakeholders to analyse the alignment between organisations’ policies and their sustainability concerns and to assess corporations’ performance.

Materiality aims to determine the social and environmental issues that present risks or opportunities to companies and those of most concern to internal and external stakeholders (Eccles et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2016b). The materiality principle requires companies to report any topic that may be considered material, both because of its significance for the reporting organisation and because of its potential influence on stakeholders’ decisions and assessments.

Implementing the materiality principle in sustainability management and reporting presents several difficulties. It requires expanding existing accounting mechanisms to incorporate a broader range of social, environmental and economic impacts and interactions into the accounting information and risk assessments (Unerman & Chapman, 2014). The discretion degree is greater in non-financial reporting because the dynamics and characteristics of social and environmental information differ from those in the economic dimension, where the commensuration procedure is globally known (Puroila & Mäkelä, 2019). Finally, the lack of detailed guidance in determining what material is causes differences in how companies apply the materiality principle (Lai et al., 2017).

This paper adopts an industry-based approach and aims to contribute to a better understanding of materiality in sustainability reporting in the telecommunications industry. The telecommunications industry was selected because of its impressive growth in recent years, its significant social and environmental impacts, the few studies about sustainability in this industry, and its long-term relationship with customers.

This study aims to gain knowledge on the key social, environmental and economic issues addressed by the telecommunication industry, assessing the internal coherence of their sustainability reports and identifying potential problems and opportunities in considering materiality from a sectorial perspective. This study contributes to the current discussion on applying the materiality principle in sustainability reporting in three directions. First, the paper proposes a novel quantitative approach to hierarchically assess sustainability reports’ materiality and quality based on the GRI indicators. Second, this paper delves into the study of materiality as a key factor in defining the content of sustainability reports and their homogeneity at the sectoral level. Finally, the paper presents a framework to assess the coherency between the materiality analysis conducted by companies and the materiality of the GRI indicators they declare.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical background of sustainability disclosure and materiality in sustainability reports and their particularities in the telecommunications industry. Section 3 presents the telecommunications industry and the selected sample. Section 4 explains the research method in a manner it can be used to reproduce the research with the same or a different sample of companies in a specific industry. The results are then presented in Sect. 5. Finally, Sect. 6 discusses the results, and conclusions are given in Sect. 7.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Sustainability reporting

Sustainability reporting is aimed at broadening the issues organisations report. It demonstrates the self-regulating capacity of companies offering a mechanism to improve companies’ social and environmental performance and represents a prime instrument for managing stakeholder engagement (Mio et al., 2020). The existing literature around sustainability reporting generally uses two main theories to support the new contributions. Both theories are complementary (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014) and part of the system-oriented theories (Sony & Naik, 2020) since both pay attention to information and disclosure in the relationship of organisations with their environment. Those theories are the legitimacy theory and the stakeholder theory, and scholars are increasingly defending their use because they allow partially explain the adoption of sustainable practices within organisations (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014; Kopnina, 2019).

Legitimacy is defined by Suchman (1995) as a “generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions” (Hamm et al., 2022). Therefore, the legitimacy of an enterprise depends on how stakeholders’ issues mesh with the identity of the firms (Bundy et al., 2013). Legitimacy theory poses a major concern for organisations due to society would expect firms’ benefits to be more significant than the cost they generate to society (Mio et al., 2020). In this regard, sustainable reporting can be understood as a way to improve their relationship with society (Machado et al., 2020). As a result, organisations need to act within the boundaries and norms of the societies in which they operate, seeking to meet community expectations (Mio et al., 2020).

As far as community expectations vary across time and legitimacy gaps may appear, organisations need to disclose how they are changing to meet the new requirements or explain why a gap is not yet managed (Guix et al., 2019). In this context, sustainability reports can be viewed as the tool companies use to respond to society’s transparency claims and justify their activities (Dumay et al., 2015). In a later stage, sustainability reports may serve society as a basis to create value judgments about the actions of companies, having the ability to favour or hinder the continuity of companies (Deegan, 2007; Martins, 2018; Phillips et al., 2003). Thus, companies are welcomed to promote the disclosure of positive aspects and goals reached and inform society about their activities. Nonetheless, to retain the owned level of legitimacy, corporations may reduce the amount of negative information disclosed in their sustainability reports, just sharing it when society asks for explanations about a concrete issue (Zharfpeykan, 2021).

Stakeholder theory (Ceulemans et al., 2015; Freeman et al., 2007) defends that companies must strategically address the needs and concerns of those groups who affect or are affected by the achievement of their objectives. The influence and value of the diverse stakeholder groups are crucial for organisations’ success, and hence, organisations need to engage their stakeholders to reduce potential conflicts with them and to grant the success of their strategies. As Lindblom (1994) argues, an organisation may use voluntary sustainability reporting to communicate with its stakeholders to close the information asymmetries (Fuhrmann et al., 2016).

Focusing on stakeholder engagement for sustainability reporting, some studies find that companies usually fail to provide full disclosure on how stakeholders have been engaged in defining the report content and how companies have responded to the stakeholder concerns (Diouf & Boiral, 2017; Manetti, 2011; Moratis & Brandt, 2017). The literature highlights the need for effective engagement and evidence that using generic categories of stakeholders with fixed members does not reflect how the groups move and change over time (Anbarasan & Sushil, 2018; Mura et al., 2018; Ruiz et al., 2021), resulting in reports that do not successfully “reach and accomplish stakeholders needs of information” (Ferrer-Serrano et al., 2022; Lozano & Garcia, 2020).

Therefore, it is expected that companies use their reports to meet the stakeholders’ and society’s expectations and transparency demands (Andrew & Baker, 2020). To this end, a proper engagement process aimed at defining material issues is essential, as well as considering any source of external information that may contribute to defining the sustainability reports’ content. Sustainability reporting remains unregulated in some countries (Machado et al., 2020). Due to the lack of regulation, criticism of the quality and effectiveness of social reporting has increased. Among others, several scholars note that sustainability reports show incomplete and irrelevant information for stakeholders (Cho et al., 2015), which is generally considered too generic and lacking detailed and quantifiable measures and comparable information (Ruiz et al., 2021; Zharfpeykan, 2021). The literature also evidences the fact that sustainability reports, on average, tend to be biased and self-laudatory (Cho et al., 2015) with minimal disclosure of negative information (Machado et al., 2020). Companies tend to report irrelevant issues where they perform well and hinder major issues where their performance does not match stakeholder criteria, avoiding sharing any information that may reduce the positive perception that society has to replace it with mistrust (Font et al., 2016).

In the context of our research, we expect that the awareness of responding to societal concerns and effective stakeholder engagement will result in high-quality reports with well-defined material issues, explicit and extensive descriptions of the materiality analysis process and lack of inconsistencies that could threaten the reputation of the reporting company and its licence to operate.

2.2 Materiality in sustainability reporting

The concept of materiality has been widely discussed in the financial accounting literature, and it is generally treated as a key element in the definition of company reports. According to the definitions provided by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (D’Adamo, 2022; Financial Accounting Standards Board, 2008) and the International Accounting Standard Board (International Accounting Standards Board & IFRS Foundation, 2015), materiality provides a threshold or cut-off point between the important and the trivial issues. Thus, in its financial accounting scope, materiality establishes the threshold between what is important enough for investors’ decision-making and what needs to be reported.

Sustainability reporting complements financial accounting, and it is expected to provide a complete view of a company’s performance and value creation on the triple bottom line (Machado et al., 2020; Moneva & Cuellar, 2009; Murningham, 2013). Materiality analysis in the context of sustainability reporting is intended to help companies to judge and evaluate what information should and should not be included in their reports (Edgley et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2016a). Thus, the materiality analysis conditions the quantity and quality of the disclosed information (Eccles & Youmans, 2016; Puroila & Mäkelä, 2019). According to Whitehead (2017), the focus on materiality is swiftly growing as it is expected to serve as a sustainability assessment tool and a filter to determine the environmental, social and governance information that is useful to decision-makers.

Several studies focus on the difficulty for companies to elaborate the materiality analysis to make a consensus on what is relevant and what is not, mainly due to the diversity of stakeholders and information requirements (Puroila & Mäkelä, 2019; Steenkamp, 2018). Therefore, the materiality definition becomes a necessary but challenging requirement of sustainability reporting, and it relies on, and it is the basis for proper stakeholder engagement. Despite the relevance of defining materiality, there is no globally accepted model for materiality analysis to determine relevant issues following stakeholders’ needs systematically.

According to GRI, “material topics for a reporting organisation should include those topics that have a direct or indirect impact on an organisation’s ability to create, preserve or erode economic, environmental and social value for itself, its stakeholders and society at large” (Global Reporting Initiative, 2014; Vitolla et al., 2019). Similarly, the International Integrated Reporting Council (International Integrated Report Council, 2013) defends that in order to determine material matters, a company should consider, among others, “one or more of the capitals it uses or affects”. From those definitions, it is expected that, independently of their strategy, companies with shared stakeholders or using the same capitals should coincide in several of their material issues, so companies within the same industry or sector should do.

Due to the diversity of industries and their social and environmental impacts (Global Reporting Initiative, 2013b; Machado et al., 2020), materiality standards at the industry level may help companies precisely measure and report on some sustainability dimensions. Focusing on the genuinely material issues of a particular company or industry may help companies maximise their returns for themselves and their stakeholders due to the investments done in sustainability management (Boerner et al., 2014; Mishenin et al., 2018). Standards may provide stakeholders with a valuable framework to assess performance and compare among companies over time. An industry-specific approach focused on a limited number of the most relevant issues may improve utility and comparability for stakeholders. Moreover, sectoral materiality definitions may serve as a reference for companies in their materiality definition process.

For those and other reasons, some studies suggest that sector-specific frameworks for materiality could help companies determine the content of their reports. By employing guidance that identifies the environmental, social and governance issues that are material to a sector and how best to report on them, companies will have much more straightforward guidance on what and how to report (Eccles et al., 2012; Lozano, 2020).

Several research articles to date suggest that companies use materiality analysis as a social construct to legitimise the content of their reports. Through an opportunistic definition of materiality, companies can promote the positive aspects of their management and avoid disclosing those issues where their actions could result in a loss of legitimacy or a significant reduction in their business activities (Brunsson, 1993; Lai et al., 2017). This loss of legitimacy may be aggravated by the fact that there is no universal model to select the stakeholders to be included in the materiality analysis (Maniora, 2018; Puroila & Mäkelä, 2019; Unerman & Zappettini, 2014) nor to monitor their interests changes over time (Brown et al., 2009; Diouf & Boiral, 2017).

The literature also evidences that materiality is not the only factor that defines the content of sustainability reports. Reports tend to include not material issues (Dumay et al., 2015), and some firms tend to give priority to the contents they consider to be of interest to specific stakeholders, mainly shareholders and investors, without arguing their relevance compared to other stakeholders (Perrault, 2017). Furthermore, some recent studies (Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2021; Zharfpeykan, 2021) state how companies are using their sustainability reports and their materiality matrices to show they report the information relevant to the stakeholders. Nonetheless, the information considered important is sometimes not shown in the document, and the matrix is just used to improve the image of the company. This paper uses the legitimacy and stakeholder theories as biases in determining material issues and reported contents.

3 Case study description

3.1 The telecommunications industry

The telecommunications industry consists of companies providing a wide range of services grouped into two main segments. On the one hand, wireless services provide direct communication through radio-based cellular networks and operate and maintain the associated switching and transmission facilities. On the other hand, the wireline segment provides local and long-distance voice, voice-over-internet protocol, telephone, television, and broadband Internet services over an expanding network of fibre-optic cables (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, 2014). However, information and communication technologies evolve fast, and the telecommunications industry is constantly adapting its infrastructures to provide newer and improved communications services.

The industry was considered interesting for several reasons: First, because it is experiencing high economic growth due to the significant innovations in information and communication technologies and due to the globalisation of information and markets (Pradhan et al., 2014). Second, because of the social and environmental impacts of the services they provide (phone calling or Internet accessing, among others). These services are essential in many fields of modern lives, but the infrastructure and devices on which they are based require significant energy consumption, land use and electronic waste. Third, because as far as we know, few studies analyse the industry in terms of sustainability and social responsibility issues (Bouten & Hoozée, 2015). Finally, because telecommunications income mainly comes from ongoing service subscriptions, which justifies the need for companies to maintain continuous engagement with stakeholders in general and consumers.

3.2 CSR and materiality in the telecommunications industry

Corporate sustainability management varies across industries, and even though the telecommunications industry is experiencing considerable development, the study of sustainability issues has remained an under-researched area (Kang et al., 2010). The telecommunications industry can have a significant influence on social and environmental aspects as a result of a wide range of impacts, such as human changes in mobility patterns, information access, communication opportunities, energy consumption, land use, or electromagnetic radiation, among others (Chan et al., 2016).

There can be found some international initiatives aimed at defining materiality in the telecommunications industry. Among others, those developed by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Global Accountancy Institute, Inc. (GAII), occupy a suitable place.

The SASB released the latest provisional standard for the telecommunications industry in April 2014 (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, 2014). In this standard, the SASB identifies six material aspects to be reported: Environmental footprint of operations; Data privacy; Data security; Product end-of-life management; Managing systemic risks from technology disruptions; and Competitive behaviour.

Using a different approach to identify the most relevant sustainability issues, the GAII identifies sectorial materiality by analysing the GRI sustainability reports of corporations (Boerner et al., 2014). Their study assumes that material information about organisations regarding economic, environmental, and social strategies, policies, performance, achievements, and engagements is the information companies include in their sustainability reports. After analysing the sustainability reports of 70 companies in the telecommunication industry, they find out “Product responsibility” as the most material GRI category and “Environment” as the less material one. Table 1 summarises their results.

The Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) proposes over 50 aspects grouping the most relevant material issues of the telecommunications industry. Those aspects are organised into 10 global categories: Climate change; Waste and material use; Access to ICT; Freedom of expression; Privacy and security; Employee relationship; Customer relationship; Supply chain; Product use issues, and Economic Development. The studies mentioned above show the diversity and lack of consensus on material issues. These results may be influenced by the definition of materiality employed, the initial set of issues, the process used to assess the materiality of issues, and the sample and stakeholders involved.

3.3 Sample

This research examines five telecommunications companies: Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, Telefónica, Orange and BT, selected based on the following criteria. First, the sample is limited to European companies, as they have the most prominent presence in the GRI Sustainability Reports database, and they lead sustainability indices such as the FTSE4Good Developed, with 378 European enterprises, 250 from America, 192 from Asia and 58 from Oceania (FTSE Russel, 2017). Second, according to the annual economic report developed by the European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association (European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association, 2016), the companies represent the top five European communications providers by revenue, and they are among the top 15 global companies (see Table 2). The world market is led by two companies in the USA, AT&T, with revenues of 132.4 billion euros, and Verizon, with revenues of 132.4 billion euros (European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association, 2016).

4 Research method

This empirical study takes the form of the descriptive and exploratory transversal analysis of CSR reports of a sample of companies. More concretely, it is conducted a qualitative and quantitative analysis of contents related to materiality and reported indicators. Qualitative data are extracted from the reports, interpreted, tabulated using quantitative values and processed to draw conclusions and contribute to the objectives of this research.

According to these objectives, the analysis is focused on one single industry, the telecommunications industry. We assume that companies should behave similarly in terms of information disclosure within a single industry and share a similar set of material issues. Furthermore, by analysing the sustainability disclosure of the leading companies within a single industry, we expect to identify a common set of reporting practices and material issues, which may help other companies and internal and external stakeholders.

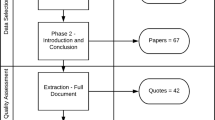

The research method is composed of a first phase, during which qualitative data are collected at a company level, analysed, organised, and tabulated with quantitative values. Then, by using two independent methods, scores are calculated to assess materiality and reporting level, and coherence is explored. The outputs of the three phases are finally analysed and discussed to extract conclusions. Figure 1 depicts the research method and the main outputs of each phase.

4.1 Data collection and qualitative analysis

The research method begins with a qualitative analysis of the sustainability reports and other formal documents related to sustainability issues. In these documents, information related to the identification and involvement of stakeholders is firstly sought and compiled, as well as the materiality definition process, the materiality matrix, or a set of material aspects, and the GRI index, a specific requirement of GRI reports where companies summarise the contents of their reports, and where they declare the indicators they consider material, and the indicators they disclose in their reports. The analysis is conducted based on a regular GRI report structure and by searching a set of keywords, including “materiality”, “stakeholders”, or “engagement”. The search begins with the sustainability reports published in the GRI Sustainability Disclosure DatabaseFootnote 1, and then, it is extended to other documents in those cases where companies declare in their reports that they disclose other contents related to our search in external sources. Some studies connect the integrated reporting framework (<IR>) and materiality and defend the advantages of considering the material issues to define a sustainable strategy and the topics to report (Lai et al., 2017; Stubbs & Higgins, 2014). However, this paper proposes to focus firstly on GRI reports. The reason resides in the fact that, as Stubbs and Higgins (2014) state, some <IR> adopters do not define a precise materiality analysis, but instead, they focus on reporting the most strategic issues rather than others which are less important for the business.

In relation to information linked to stakeholder identification and engagement processes and the materiality definition process, the qualitative analysis aims to understand better the way companies act. To this end, at this point, our research method requires identifying the stakeholders’ companies engage with, how they engage with them, and the resources or frameworks used to these ends. The self-defined material aspects are then extracted from the definition of materiality that companies include in their reports. Only the set of material aspects and their definitions result in interest for this research, so other data, such as aspects’ position within materiality matrices or materiality ranks, may be ignored. In addition, the GRI indicators are linked to the list of self-defined material aspects. These links can be identified with the support of the GRI Implementation Manual (Global Reporting Initiative, 2013a) and the experience of the authors. Note that aspects, as defined by companies, can be very varied, so aspects considered too broad or outside the scope of social, environmental, or economic performance might be left without linked indicators.

Finally, based on the GRI index, numeric values are used to record the materiality and reporting level that companies declare for each indicator. In the case of materiality, value 100 is used for indicators “self-material” and value 0 for “declared not material”. In a similar way, in the case of reporting levels, value 100 is used for indicators “declared fully reported”, 50 for “declared partially reported,” and 0 for “declared not reported”.

A final numeric value is finally calculated for each indicator as to the absolute difference between the materiality value and the reporting level value. This value represents whether the company is incoherent in the treatment of the indicator. Incoherence in the indicator is recorded with 100 to indicate fully over- or underreported and 50 to indicate partially over or underreported. A value of 0 represents the indicator that is consistently reported.

It is important to note that the application of this research method does not require checking whether indicators marked as reported or partially reported in the GRI indexes are included in the reports. Hence, data collection trusts the company’s self-declaration of indicators reporting accomplishment. GRI (Global Reporting Initiative, 2013b) highlights the importance of report verification because it gives an extra degree of trust and credibility, reduces the risk of introducing vague and non-important information, and sets a more robust reporting and management system.

4.2 GRI scoring method

This paper proposes a hierarchical arithmetic mean approach to aggregate the collected data and calculate scores, which are ultimately aimed at assessing the materiality and reporting level of reports based on the GRI indicators hierarchy. The hierarchical arithmetic mean method has previously been used in other research linked to sustainability reporting assessment (Ching et al., 2013, 2014) since it allows to compose of diverse scores for GRI aspects subcategories and categories hierarchically. For this research, three main scores are calculated using the GRI hierarchy:

-

The GRI materiality score measures the degree to which the hierarchy defined by GRI is material for the reporting company. The higher the value of the score, the higher proportion of the hierarchy is material for the company. A score of 0 points means any of the GRI indicators is declared material, while 100 points mean all the GRI indicators are material.

-

The GRI adherence score offers a measure of the degree to which the sustainability report includes all the indicators defined by GRI. The higher the value of the score, the higher proportion of the hierarchy is reported. A score of 0 points means no one of the GRI indicators is reported, while a score of 100 points means all the GRI indicators are fully reported.

-

The GRI incoherence score measures the degree to with the company reports incoherently based on the definition of the materiality of indicators and their reporting level. The higher the value of the score, the higher proportion of the hierarchy is incoherently treated. A score of 0 points means no one of the GRI indicators has been treated incoherently, while a score of 100 points means that all the GRI indicators have been treated incoherently.

For each company in the sample, the proposed method calculates the scores by calculating the arithmetic mean of the values previously assigned to the GRI indicators within the aspect (0 or 100 for materiality values, 0, 50, or 100 for reporting level values). As an example of the process, material values assigned to indicators EC1 to EC4 in the data collection phase are aggregated in a materiality score for the economic performance aspect by calculating their arithmetic mean (see Annex I consult the whole hierarchy and definition of GRI indicators).

Then, average scores for subcategories—only for social aspects as reflected in the GRI aspects taxonomy—are calculated considering the average scores of aspects within the subcategories, which are finally used to calculate the materiality scores for the social, environmental, and economic categories. Therefore, scores are calculated in a hierarchical process, assigning the same weight to each element at the same level of aggregation (indicators first, subcategories then, and categories at the end). Note that scores for reporting levels do not represent a total percentage of GRI indicators declared material or reported by companies but a hierarchical, weighted average.

The scores at the different levels for the companies in the sample are finally aggregated employing arithmetic mean and standard deviation to offer a proxy for the materiality and reporting level and the consensus among companies of the analysed industry. Moreover, the individual scores calculated in this manner may serve as quantitative variables to be used as inputs in diverse statistical tests.

4.3 Scoring method with self-defined materiality

Similar scoring methods are used to assess the materiality and quality of reports in terms of the material aspects identified by companies. These aspects are not offered in a hierarchical structure, nor are they linked to GRI aspects. These scores are calculated considering all aspects contributing equally.

Based on the linkage between the self-defined material aspects and GRI indicators, scores for materiality and reporting adherence of companies’ material aspects are calculated by aggregating the numeric values of the GRI indicators related to each specific aspect.

The inconsistency is not assessed using a similar score, as the different conceptual levels between self-defined aspects and GRI indicators may conditionate the results. However, it is still possible to analyse the coherency the companies show in relation to the self-defined material aspects and the materiality of indicators. In this regard, it is possible to identify indicators that are not considered material but are linked to self-defined material aspects and indicators declared material that cannot be associated with any self-defined material aspect.

5 Results

The proposed method begins with the identification of data sources, which in the first attempt are limited to the GRI reports of the five companies in the sample. In those cases where information is claimed to be included in other documents, they have also been added to the set of analysed documents. Table 3 summarises the documents analysed and the contents found in them.

Using the abovementioned documents, the following data have been harvested for each company in the sample:

-

Stakeholders’ classification.

-

Stakeholders’ engagement and materiality definition processes.

-

Numeric values for declared reporting and materiality levels.

-

Self-defined material issues.

Moreover, the authors have calculated the difference between the materiality and reporting level values for each indicator as a proxy of incoherency in the treatment of each indicator. Finally, a linkage between self-defined material issues and GRI indicators has been defined according to the authors’ subjective criteria (see Annex IV).

In relation to the confidence of the information included in GRI reports, all the reports have been verified by reputed auditing firms (see Table 4). All the companies included in their reports the reviews made by the verifiers, and all conclude there is neither any relevant lack of information nor the enterprises have stated something that the reviewing company stated as not reported.

5.1 Qualitative analysis

The qualitative analysis of the reports evidences that the companies offer limited information related to stakeholders identification and engagement processes and the materiality definition process, which is summarised in Annex II.

Concerning stakeholder engagement, companies indicate they use various kinds of analysis to determine their main stakeholders. Two main methods predominate to identify stakeholders and to define their engagement level with them: on the one hand the opinion of internal experts, the CSR department staff or even both and on the other the opinion of external experts’ panels, external enterprises, and counsellors. The qualitative analysis also shows that none of the companies provides detailed explanations in their reports about collecting and processing those opinions or how the sources to consult are chosen.

Companies use similar terminology to define common stakeholder groups. We identify four groups for all the companies: clients and customers, employees, suppliers, and investors. Table 5 summarises the stakeholders identified by each company Governments and regulators, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and the telecommunications industry are identified as stakeholders by four of the companies.

About materiality definition, all the companies report using a mixed framework as a starting point, which combines the GeSI and the GRI sets of sustainability aspects. The materiality analysis is performed using the following methods: interactions in dialogues with stakeholders, P2P meetings, discussion forums, focus groups, social media, and participation in industry associations. Companies do not report specific information about the topics initially managed, nor a detailed explanation about the materiality analysis.

Finally, companies provide information related to materiality validity over time. Most enterprises report to review materiality issues determination every one or two years, but there is no specific information about the implications of that material issues update. Some companies also do a complete remake of the matrix could take almost 5–6 years.

5.2 Scores with GRI

Using the numeric values for materiality and reporting levels of indicators, and the numeric value representing an incoherent disclosure, the diverse GRI scores proposed in the research method have been calculated with the following results.

5.2.1 GRI materiality scores

The individual and aggregated scores in terms of materiality for the three dimensions of GRI are depicted in Fig. 2 (see Annex III for detailed numeric scores for this and ongoing figures). The GRI aspects present a materiality score of 51.4 points for the sample companies, as observed. By dimension, the most material is the economic one, with a score of 60.0 points, followed by the social (54.2 points) and the environmental (39.9 points). In terms of companies, Orange is the company that considers more material the GRI hierarchy of sustainability issues more, with a score of 85.7, and Deutsche Telekom considers the GRI hierarchy less material, with 37.4 points.

To explore whether there are differences in the scores between companies or between the three dimensions of sustainability, the study includes a non-parametric test. Concretely, the study uses the Kruskal–Wallis test to test whether samples originate from the same distribution. Table 6 summarises the results, which not rejects the null hypothesis that materiality scores of companies or dimensions come from the same distribution.

At the level of the indicators, we identify some degree of consensus in 59 out of the 91 GRI indicators. For those indicators, at least four of the five companies in the sample agree to define them as material or not material. By dimensions, 27 out of 48 social indicators are agreed by at least four companies, five out of nine in the economic dimension, and 27 out of 34 in the environmental. Therefore, in relative terms, environmental indicators present the largest consensus of indicators regarding materiality between companies in the sample. Table 7 summarises the GRI indicators according to the number of companies that consider them material and their sustainability dimension.

5.2.2 GRI adherence scores

Regarding the GRI adherence scores, the whole sample is assessed with 50.3 points. (Fig. 3). Similar to GRI materiality scores, the economic dimension is the one with a higher GRI adherence score (60.6 points), followed by social (51.1 points) and environmental (39.2 points). By companies, Orange presents the largest GRI adherence score, with 74.3 points, and Vodafone the lowest one, with 35.6.

The Kruskal–Wallis test (Table 8) rejects the null hypothesis that GRI adherence scores of dimensions come from the same distribution. In the case of GRI adherence of companies, the p value indicates the null hypothesis is accepted with a significance level p < 0.1(*).

At the level of the indicators, we identify some degree of consensus in 59 out of the 91 GRI indicators since at least four of the five companies in the sample have reported o partially reported the indicators. By dimensions, 29 out of 48 social indicators are agreed by at least four companies, six out of nine in the economic dimension, and 24 out of 34 in the environmental. Therefore, in relative terms, environmental indicators present the largest consensus to reporting practices between companies in the sample. Table 9 summarises the number of GRI indicators according to the number of companies that report or partially report them and their sustainability dimension.

5.2.3 GRI incoherence scores

The presentation of the GRI scores ends with the incoherence score. The whole sample presents a GRI incoherence score of 19.7 points (Fig. 4). The economic dimension is where companies present the most remarkable inconsistency, with an average score of 25.0 points. Inconsistency in the social dimension is assessed with 19.3 points, while the environmental dimensions result to be the one where inconsistencies are less relevant, with a score of 14.8 points. Deutsche Telekom is the company with the highest inconsistency score (40.5 points), while Telefónica is the less inconsistent company (11.3 points).

By decomposing the inconsistency score in terms of underreporting and overreporting inconsistencies, the results show that underreporting inconsistency contributes significantly. In this regard, from the 19.7 points of the GRI incoherence score, 11.9 are linked to underreported indicators, while 7.8 points come from overreporting. By dimensions, underreporting contributes to the economic, social, and environmental dimensions with 15.0, 8.6 and 12.1 points.

At the level of GRI indicators, the analysis of coherence between the materiality of indicators and their reporting level (see Table 10) reveals that four of the five companies tend to underreport indicators in their reports, being the social category the main underreported. Telefonica, on the contrary, is mainly overreporting and discloses 8 indicators that are not material for the firm.

5.3 Scores with self-defined materiality

The global materiality and adherence scores calculated according to the self-definition of material aspects are presented in Table 11. According to the results, all the indicators linked to material aspects defined by Deutsche Telecom are considered material in the GRI index since its materiality score presents a value of 100 points. On the contrary, the aspects BT-Group declared as material scored 53.7 points according to the materiality declaration of GRI indicators (see Annex IV).

Adherence scores present lower values in four of the five enterprises. Telefónica has an adherence score higher than the materiality score, which means that Telefónica overreports some indicators linked to material aspects but are declared not material—concretely HR5, PR5, and EN8. On the other hand, companies presenting an adherence score lower than the materiality score tend to underreport indicators linked to material issues and declared material in the GRI index. In both cases, incoherencies are shown.

The results also evidence some incoherencies between the self-definition of material issues and the declaration of material indicators. As Table 12 summarises, the same companies declare several material indicators that cannot be linked to any of the self-defined material aspects. Similarly, we find material aspects without linked material indicators.

6 Discussion

The results of this research could be enhanced by a deeper analysing of the materiality definitions of companies. Although all the companies include a brief description, no one of them offers information to check whether the materiality analysis has been done as requested by the GRI in its reporting principles for defining report content, more concretely, according to GRI guidance for indicator G4-18 in Implementation Manual (Global Reporting Initiative, 2013a). According to this indicator, companies should “(a) explain the process for defining the report content and the Aspect Boundaries and (b) explain how the organisation has implemented the Reporting Principles for Defining Report Content”. Instead, companies declare they have developed their materiality analysis in collaboration with their stakeholders using surveys and meetings, with no additional details. Furthermore, some of them declared to take part in some international initiatives aimed at defining materiality at an industrial level, such as the one conducted by the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (Global e-Sustainability Initiative, 2014) for the industry of Information and Communication Technologies.

Even the companies share a common core of stakeholders, and they have used common frameworks as the starting point—as advocated by Eccles et al. (2012)—it is interesting to note the apparent differences among the material aspects identified by companies. As far as we identify in their reports, no one of the companies bases its materiality definition on a standard set of sustainability issues. Each company’s material issues, even having similar names, may differ in meaning and coverage. Differences in material aspects may also confirm the great subjectivity in implementing the materiality principle and the lack of a standard process to define materiality, as identified in other research (Lai et al., 2017). The periodicity of the updates is also variable. The materiality analysis of companies presents validities from 1 to 5 years.

The lack of rigour in the definition of stakeholders and material aspects can also be observed when trying to link them to each other. As an example, Local Communities are only identified by Vodafone, but all the companies include sustainability aspects related to them. Something similar happens for other aspects, which are not associated with any of the stakeholders the company explicitly identifies. Therefore, we identify some degree of separation among the set of stakeholders a company identifies and the sustainability aspects considered material.

Regarding the documentation of materiality, Vodafone only provides a list of material issues, and the other four companies have adapted the concept of the materiality matrix initially favoured by the GRI. The relative position of aspects within the materiality matrices or materiality ranks could better assess companies and the industry (Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2021). However, this possibility has not been considered for this research, as materiality is understood as a dichotomic threshold for issues reporting.

The empirical results of this study show that, in general terms, companies agree on the relative materiality they confer to the global categories of sustainability. Despite the fact that the increasing claims for sustainable performance on social and environmental issues, and even though all the sample companies show a similar level of awareness for the three dimensions of sustainability, it is still the most material one and has a higher adherence score. That result may be evidence that the social and environmental issues are being integrated into the strategies and disclosure of companies, but the economic issues still occupy the prime role in the management and reporting of companies. This result is also aligned with previous research (Perrault, 2017; Zharfpeykan, 2021).

In relation to social and environmental aspects, the bigger scores obtained by social issues, in terms of both GRI materiality and GRI adherence, may be aligned with the fact that the telecommunications industry has a significant impact on the way of life of people, even though the GRI-G4 aspects may result too generic to encompass some of the major social impacts of the telecommunications industry. This fact may be explained by the stakeholders that the companies identify, which include some social groups such as NGOs, international organisations, or research and education institutions. The environment is not identified as a stakeholder by itself, as it is done in several cases, but we assume it is represented by the other groups.

In absolute terms, the results show some differences in the GRI materiality scores that companies in the sample confer to the global categories of sustainability, with an average standard deviation value of 17.5. The Kruskal–Wallis test results do not reject the hypothesis that GRI materiality scores for sustainability dimensions come from the same distribution. This result is in line with previous research that identifies different material definitions for diverse industries (Boerner et al., 2014).

The different strategies of each company may explain the differences between them. However, the scarce information that companies provide about stakeholder engagement and the analysis of materiality, the shared core of standard stakeholders, and the inconsistencies between the self-defined material aspects and the declaration of material indicators suggest that companies should improve their materiality analysis in the future.

The deviation is smaller for the GRI adherence score, where differences between companies are smaller due to overreported and underreported indicators, resulting in more homogenous reports. The fact that overreported and underreported indicators reduce adherence deviation in relation to materiality deviation can be seen as evidence that organisations tend to report generic sustainability issues that are scarcely relevant for stakeholders (Diouf & Boiral, 2017) instead of including specific aspects only when they are considered material.

In relation to the results about coherency in reporting practices, the results show that even if companies tend to underreport in general terms, social and environmental issues are more affected. These may be motivated because of the difficulties companies have in providing information related to those categories and because their performance is worse than stakeholders expect. By overreporting and underreporting indicators, companies may try to bias their image to stakeholders and keep the legitimacy to operate (Font et al., 2016). Companies are legally required to report on economic performance, and overreporting or underreporting economic information in sustainability reports will have a softer effect.

Incoherency could also be explained by setting reputation risk management and impression management as the intended purpose behind sustainability reporting (Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2020; Ruiz et al., 2021). From this point of view, companies can strategically disclose information to manage the perceptions of stakeholders in order to increase their reputation or to handle legitimacy threats (Guix et al., 2019).

Similarly, we finally identify some degree of mislinkage between the set of material aspects provided by companies and the declaration of materiality they offer for the GRI-G4 indicators.

Besides, it is not difficult to identify indicators that, even having a clear linkage with the material sustainability aspects identified by companies, are not considered material. A clear example of this lack of coherency among self-defined material aspects and the materiality definition of indicators can be found in Telefonica. In this example, even though the aspect “Water” is considered material for the company, no one of the GRI indicators related to water (EN8, EN9 and EN10) is considered material. Therefore, further research is needed to understand better the reasons behind this misalignment among self-defined material aspects and the materiality definition for the GRI indicators. The proposed analysis method may help companies to improve the quality of their reports.

Finally, it is possible to compare the GRI scores and the scores calculated with self-defined materiality. The materiality and adherence scores are bigger when calculated according to the material aspects that each company defines. This result is coherent with the idea that materiality analysis allows companies to improve reporting quality and reflects that the GRI hierarchy of aspects may be too generic to be used as a starting point for companies in any industry.

7 Conclusions

This paper presents a study aimed at contributing to the study of sustainability reporting practices of companies from a sectorial perspective, and it is focused on the application of the materiality principle. The research proposes a novel approach to assess the materiality and quality of sustainability reports and uses the information of well-known European companies in the telecommunications industry include in their reports to identify those aspects occupying a relevant position in their management and disclosure policies. Furthermore, the research also offers some findings of the coherence that companies in this industry show in relation to their material aspects definitions and their sustainability reports.

Although this exploratory paper is based on a small sample of companies and analyses reports in one year, all the companies have a global presence and are sector leaders in Europe. The results allow identifying some interesting issues related to the way companies report and the contents they include.

The results suggest that, in aggregate terms, the sustainability aspects proposed by the Global Reporting Initiative score 51.4/100 points in terms of material for the telecommunications industry, which indicates that the GRI hierarchy includes several aspects that are not material for the industry, some of them with the agreement of all companies in the sample.

Moreover, the results show that companies are quite coherent in relation to the indicators they declare material and the indicators they inform about. However, reports include some overreported and underreported indicators, showing some degree of incoherence between the material aspects defined by companies and the materiality declaration of indicators they do.

In global terms, companies fail to provide a detailed explanation of stakeholder engagement and the process used to define materiality. The results seem to evidence that the problem is not limited to an incomplete description, to somewhat inefficient processes, and may be conditioned by interests other than those expected.

This paper presents some clear limitations, such as those related to the sample size or the process of retrieving the information. The sample size does not allow the findings of the exploratory study to be generalised to the entire industry. Despite being the most important companies in Europe, the small sample may produce a bias in the data associated with the industry. Limiting the study to a short period of time may create a bias due to not having a comparative list of material aspects or information from previous periods. Also, the qualitative collection may be biased by the authors’ experience and limited capacity to review every detail.

7.1 Practical and theoretical implications

This article contributes to advances that can be useful for future researchers and practitioners. First, the proposed scores may serve companies in the telecommunications industry as a valuable resource for their materiality definition, as the results may help them to identify a range of social and environmental sustainability topics that cover the main risks and opportunities of the industry. The material aspects at the industry level may help companies make changes to how they operate in a direction intended to result in less unsustainable operations and better disclose their performance to the society where they operate. Materiality scores may also help stakeholders of the industry. It provides an aggregated view of the material issues that companies in the industry should consider in their managerial and reporting activities and can be used to assess the compromise of companies in relation to sustainability issues.

Second, the coherency analysis may be replicated for different purposes. Before disclosing their sustainability reports, companies identify infra-reported and overreported indicators and inform about why the material and reported indicators do not coincide. Stakeholders in assessing the sustainability performance of corporations, since infra- and overreporting companies may evidence greenwashing intents when overreport indicators with good performance and infra-report indicators with lousy performance.

Finally, other researchers or practitioners can use the proposed scorings and the analysis method for several purposes. For example, a similar research design could be applied to different industries, with the purpose of knowing the degree of coherence in terms of materiality and reporting level that exists in those sectors, but also to perform inter-industry comparisons.

The completion of this study has brought to light a set of topics for future research. It would be interesting to gain knowledge of the process companies have employed to identify and engage with stakeholders and the analysis they have conducted to identify their material aspects since they could help clarify the differences in materiality detected among companies. Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyse why the companies present inconsistencies in their reports, both in terms of GRI indicators materiality and reporting and in terms of self-defined material aspects and the materiality declaration of GRI indicators.

Data availability statement

There is no additional data set available related to this article. Every data use is stated in the document.

Notes

Database available from http://database.globalreporting.org/.

References

Anbarasan, P., & Sushil, P. (2018). Stakeholder engagement in sustainable enterprise: Evolving a conceptual framework, and a case study of ITC. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(3), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1999

Andrew, J., & Baker, M. (2020). Corporate social responsibility reporting: The last 40 years and a path to sharing future insights. Abacus, 56(1), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12181

Boerner, H., Coppola, L. D., Jardieanu, L. A., & Viteri, S. (2014). Sustainability: What matters? http://www.ga-institute.com/fileadmin/user_upload/Reports/G_A_sustainability_-_what_matters_-FULL_REPORT.pdf

Bouten, L., & Hoozée, S. (2015). Challenges in sustainability and integrated reporting. Issues in Accounting Education. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-51093

Brown, H. S., de Jong, M., & Levy, D. L. (2009). Building institutions based on information disclosure: Lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.12.009

Brunsson, N. (1993). Ideas and actions: Justification and hypocrisy as alternatives to control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 18(6), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)90001-M

Bundy, J., Shropshire, C., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2013). Strategic cognition and issue salience: Toward an explanation of firm responsiveness to stakeholder concerns. Academy of Management Review, 38(3), 352–376.

Ceulemans, K., Lozano, R., & Alonso-Almeida, M. M. (2015). Sustainability reporting in higher education: Interconnecting the reporting process and organisational change management for sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland), 7(7), 8881–8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7078881

Chan, C. A., Gygax, A. F., Leckie, C., Wong, E., Nirmalathas, A., & Hinton, K. (2016). Telecommunications energy and greenhouse gas emissions management for future network growth. Applied Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.01.007

Ching, H. Y., Gerab, F., & Toste, T. H. (2013). Analysis of sustainability reports and quality of information disclosed of top Brazilian companies. International Business Research. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v6n10p62

Ching, H. Y., Gerab, F., & Toste, T. H. (2014). Scoring sustainability reports using GRI indicators: A study based on ISE and FTSE4Good price indexes. Journal of Management Research. https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v6i3.5333

Cho, C. H., Laine, M., Roberts, R. W., & Rodrigue, M. (2015). Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 40, 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.12.003

D’Adamo, I. (2022). The analytic hierarchy process as an innovative way to enable stakeholder engagement for sustainability reporting in the food industry. Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02700-0

Deegan, C. (2007). Organizational legitimacy as a motive for sustainability reporting. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/NOE0415384889.ch7

Diouf, D., & Boiral, O. (2017). The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2015-2044

Dumay, J., Frost, G., & Beck, C. (2015). Material legitimacy blending organisational and stakeholder concerns through non-financial information disclosures. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11(1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-06-2013-0057

Eccles, R. G., Krzus, M. P., & Ribot, S. (2015). Models of best practice in integrated reporting 2015. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 27(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12123

Eccles, R. G., Krzus, M. P., Rogers, J., & Serafeim, G. (2012). The need for sector-specific materiality and sustainability reporting standards. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2012.00380.x

Eccles, R. G., & Youmans, T. (2016). Materiality in corporate governance: The statement of significant audiences and materiality. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 28(2), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12173

Edgley, C., Jones, M. J., & Atkins, J. (2015). The adoption of the materiality concept in social and environmental reporting assurance: A field study approach. The British Accounting Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.11.001

Escrig-Olmedo, E., Fernández-Izquierdo, M., Ferrero-Ferrero, I., Rivera-Lirio, J., & Muñoz-Torres, M. (2019). Rating the raters: Evaluating how ESG rating agencies integrate sustainability principles. Sustainability, 11(3), 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030915

European TelecommunIcations network operators’ Association. (2016). Annual economic report 2016. European TelecommunIcations network operators’ Association.

Fernando, S., & Lawrence, S. (2014). A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory. The Journal of Theoretical Accounting, 10(1), 149–178.

Ferrero-Ferrero, I., León, R., & Muñoz-Torres, M. J. (2020). Sustainability materiality matrices in doubt: May prioritizations of aspects overestimate environmental performance? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1766427

Ferrero-Ferrero, I., León, R., & Muñoz-Torres, M. J. (2021). Sustainability materiality matrices in doubt: May prioritizations of aspects overestimate environmental performance? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(3), 432–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1766427

Ferrer-Serrano, M., Fuentelsaz, L., & Latorre-Martinez, M. P. (2022). Examining knowledge transfer and networks: An overview of the last twenty years. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(8), 2007–2037. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2021-0265

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2008). Statement of financial accounting concepts no.2. Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Font, X., Guix, M., & Bonilla-Priego, M. J. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tourism Management, 53(April), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.007

Freeman, R., Harrinson, J., & Wicks, A. (2007). Managing for stakeholder: Survival, reputation and success (1st ed.). Yale University Press.

Fuhrmann, S., Ott, C., Looks, E., Guenther, T. W., Fuhrmann, S., Ott, C., Looks, E., & Guenther, T. W. (2016). The contents of assurance statements for sustainability reports and information asymmetry The contents of assurance statements for sustainability reports and information asymmetry. Accounting and Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2016.1263550

Global e-Sustainability Initiative. (2014). ICT and sustainable development. A materiality assessment for the ICT industry by the global e-sustainability initiative. Global e-Sustainability Initiative.

Global Reporting Initiative. (2013). GRI G4 sustainability reporting guidelines: Implementation manual. Global Reporting Initiative.

Global Reporting Initiative. (2013). GRI G4 sustainability reporting guidelines: Reporting principles and standard disclosure. Global Reporting Initiative.

Global Reporting Initiative. (2014). Materiality in the context of the GRI reporting framework. Global Reporting Initiative.

Gray, R., Adams, C. A., & Owen, D. (2014). Accountability, social responsibility and sustainability. Pearson Education Limited.

Guix, M., Font, X., & Bonilla-Priego, M. J. (2019). Materiality: Stakeholder accountability choices in hotels’ sustainability reports. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2321–2338. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0366

Hamm, J. A., Wolfe, S. E., Cavanagh, C., & Lee, S. (2022). (Re) Organizing legitimacy theory. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 27, 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12199

International Accounting Standards Board, & IFRS Foundation. (2015). Exposure draft: Conceptual framework for financial reporting. International Accounting Standards Board, & IFRS Foundation.

International Integrated Report Council. (2013). Materiality. Background paper for <IRA>. International Integrated Report Council.

Jones, P., Comfort, D., & Hillier, D. (2016). Materiality in corporate sustainability reporting within UK retailing. Journal of Public Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1570

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016b). Sustainability in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0572

Kang, Y., Ryu, M.-H., & Kim, S. (2010). Exploring sustainability management for telecommunications services: A case study of two Korean companies. Journal of World Business. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.08.003

Kopnina, H. (2019). Green-washing or best case practices? Using circular economy and Cradle to Cradle case studies in business education. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219, 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.005

Lai, A., Melloni, G., & Stacchezzini, R. (2017). What does materiality mean to integrated reporting preparers? An empirical exploration. Meditari Accountancy Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2017-0113

Lindblom, C. K. (1994). The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. In Critical perspectives on accounting conference, New York, 1994.

Lozano, R. (2020). Analysing the use of tools, initiatives, and approaches to promote sustainability in corporations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 982–998. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1860

Lozano, R., & Garcia, I. (2020). Scrutinizing sustainability change and its institutionalization in organizations. Frontiers in Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2020.00001

Machado, B. A. A., Dias, L. C. P., & Fonseca, A. (2020). Transparency of materiality analysis in GRI-based sustainability reports. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2066

Manetti, G. (2011). The quality of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: empirical evidence and critical points. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.255

Maniora, J. (2018). Mismanagement of sustainability: What business strategy makes the difference? Empirical evidence from the USA. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3819-0

Martins, N. O. (2018). The classical circular economy, sraffian ecological economics and the capabilities approach. Ecological Economics, 145(August 2017), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.026

Mio, C., Fasan, M., & Costantini, A. (2020). Materiality in integrated and sustainability reporting: A paradigm shift? Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(1), 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2390

Mishenin, Y., Koblianska, I., Medvid, V., & Maistrenko, Y. (2018). Sustainable regional development policy formation: Role of industrial ecology and logistics. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 6(1), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.6.1(20)

Moneva, J. M., & Cuellar, B. (2009). The value relevance of financial and non-financial environmental reporting. Environmental and Resource Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-009-9294-4

Moratis, L., & Brandt, S. (2017). Corporate stakeholder responsiveness? Exploring the state and quality of GRI-based stakeholder engagement disclosures of European firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1408

Mura, M., Longo, M., Micheli, P., & Bolzani, D. (2018). The evolution of sustainability measurement research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(3), 661–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12179

Murningham, M. (2013). Redefining materiality II: Why it matters, whose involved, and what it means for corporate leaders and boards. AccountAbility, 17, 2020.

Perrault, E. (2017). A ‘names-and-faces approach’ to stakeholder identification and salience: A matter of status. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2929-1

Phillips, R., Freeman, R. E., & Wicks, A. C. (2003). What stakeholder theory is not. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 479–502. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200313434

Pradhan, R. P., Arvin, M. B., Norman, N. R., & Bele, S. K. (2014). Economic growth and the development of telecommunications infrastructure in the G-20 countries: A panel-VAR approach. Telecommunications Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2014.03.001

Puroila, J., & Mäkelä, H. (2019). Matter of opinion: Exploring the socio-political nature of materiality disclosures in sustainability reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(4), 1043–1072. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2016-2788

Ruiz, S., Romero, S., & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2021). Stakeholder engagement is evolving: Do investors play a main role? Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 1105–1120. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2674

FTSE Russel. (2017). FTSE4Good Index Series-FTSE Russell Factsheet as at 29 September 2017. http://www.Ftse.com/Analytics/FactSheets/Temp/22d83a84-974f-4c34-9a5a-5860abbb93e7.pdf

Salesa, A., León, R., & Moneva, J. M. (2022). Is business research shaping the circle? Systematic and bibliometric review of circular economy research. Sustainability, 14(14), 8306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148306

Sony, M., & Naik, S. (2020). Technology in Society Industry 4.0 integration with socio-technical systems theory: A systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Technology in Society, 61(August 2019), 101248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101248

Steenkamp, N. (2018). Top ten South African companies’ disclosure of materiality determination process and material issues in integrated reports. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-01-2017-0002

Stubbs, W., & Higgins, C. (2014). Integrated reporting and internal mechanisms of change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1279

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. (2014). Telecommunications sustainability accounting standard: April 2014 provisional standard. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

Unerman, J., & Chapman, C. (2014). Academic contributions to enhancing accounting for sustainable development. Accounting, Organizations and Society. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.07.003

Unerman, J., & Zappettini, F. (2014). Incorporating materiality considerations into analyses of absence from sustainability reporting. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2014.965262

Vitolla, F., Raimo, N., & Rubino, M. (2019). Board characteristics and integrated reporting quality: An agency theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1879

Whitehead, J. (2017). Prioritizing sustainability indicators: Using materiality analysis to guide sustainability assessment and strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1928

Zharfpeykan, R. (2021). Representative account or greenwashing? Voluntary sustainability reports in Australia’s mining/metals and financial services industries. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(4), 2209–2223. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2744

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the Government of Aragon in the framework of the “Group on Socio-economy and Sustainability” Ref. S33_20R, by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness on the “Eco-Circular Project” Ref. ECO2016-74920-C2-1-R, and by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities on the “Circular Tax Project” Ref. PID2019-107822RB-I00”.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

León, R., Salesa, A. Is sustainability reporting disclosing what is relevant? Assessing materiality accuracy in the Spanish telecommunication industry. Environ Dev Sustain (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03537-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03537-x