Abstract

This paper analyses the consequences for the European patent system of the recently ratified London Agreement, which aims to reduce the translation requirements for patent validation procedures in 15 out of 34 national patent offices. The simulations suggest that the cost of patenting has been reduced by 20–30% since the enforcement of the LA. With an average translation cost saving of €3,600 per patent, the total savings for the business sector amount to about €220 millions. The fee elasticity of patents being about −0.4, one may expect an increase in patent filings of 8–12%. Despite the translation cost savings, the relative cost of a European patent validated in six (thirteen) countries is still at least five (seven) times higher than in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The seven signatory states in 1978 were Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Switzerland and The United Kingdom.

For instance, Single Market Commissioner Charlie McCreevy in his statement on 3rd April 2007 said: “Patents are a driving force for promoting innovation, growth and competitiveness but the single market for patents is still incomplete. … In today’s increasingly competitive global economy, Europe cannot afford to lose ground in an area as crucial as patent policy.” www.iht.com/articles/2007/04/03/business/ip.php

Patent applications can also be filed in the national language of the EPC contracting state. However, the translation into one of the three EPO official languages has to be submitted within 3 months of the filing date.

i.e., the first time an application is filed, generally at a national patent office; cf. Stevnsborg and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (2007) for a detailed description of the various routes that can be used to reach the EPO.

Novelty, non-prejudicial disclosures, inventive step, and industrial applicability requirements are set according to art. 54, art. 55, art. 56 and art. 57 of the EPC, respectively.

Art 137 of the EPC.

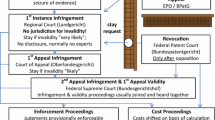

Mejer and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (2009), who provide several case studies of litigations that yielded opposite results in various countries. One of the patent infringements lawsuit concerns Document Security Systems (DSS) v. European Central Bank (ECB). The US company DSS sued the ECB in August 2005 at the European Court of First Instance, alleging that the euro banknotes produced by the ECB infringe its European patent EP 0455750 relating to anti-counterfeiting technology (DSS accused the ECB of infringing its technology in the production process of banknotes). Differences across jurisdictions led to uphold the patent at the court of first instance in Germany and the Netherlands but it was invalidated in France.

Note that the entry into force of the London Agreement was conditional on ratification by at least eight countries, including France, Germany, and United Kingdom (London Agreement 2000).

Once the European patent is granted, it must be validated in the desired member states to be effectively enforced. Validation fees are paid to national patent offices for the publication of the translated patent.

Harhoff et al. (2009b) classify languages according to the level of costs of translations incurred by the patent holder. In general, translations into languages spoken in central and Southeastern Europe are less expensive than translations into the Nordic languages. Ginsburgh (2005) and Fidrmuc and Ginsburgh (2007) provide theoretical and empirical evidence supporting the idea that some languages are more difficult than others, implicitly inducing higher translation costs.

Stevnsborg and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (2007) present a typology of filing strategies and discuss their impact on the examination process.

This cost can be lower as the countries that ratified the London Agreement may not require an official representative to be appointed.

At the Brazilian and Chinese patent offices the request must be performed within 3 years from the application date; in India, within 4 years from the application date and in Australia, Canada and South Korea 5 years are allowed. Since 2005 the Japanese patent office allows for a 3 years period to file the request of examination (previously it was 7 years). Cf. Lazaridis and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (2007) for the relationship between patent size and the length of examination, and van Zeebroeck (2007) for an in-depth analysis of examination duration at the European Patent Office.

References

Archontopoulos, E., Guellec, D., Stevnsborg, N., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & van Zeebroeck, N. (2007). When small is beautiful: Measuring the evolution and consequences of the voluminosity of patent applications at the EPO. Information Economics and Policy, 19(2), 103–132. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2007.01.001.

de Rassenfosse, G., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2007). Per un pugno di dollari: A first look at the price elasticity of patents. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), 588–604. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grm032.

de Rassenfosse, G., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2008). On the price elasticity of the demand for patents. ECARES Working Paper, 2008-031.

de Rassenfosse, G., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2009). A policy insight into the R&D-patent relationship. Research Policy, 38(5), 779–792.

Dernis, H., Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2001). Using patent counts for cross-country comparisons of technology output. STI Review, 27. Paris: OECD.

Ericsson, H., Hendry, D., & Mizon, G. (1998). Exogeneity, cointegration, and economic policy analysis. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 16(4), 370–387. doi:10.2307/1392607.

European Commission Communication. (2007). Enhancing the patent system in Europe. COM 165.

Fidrmuc, J., & Ginsburgh, V. (2007). Languages in the European Union: The quest for equality and its cost. European Economic Review, 51(6), 1351–1369. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2006.10.002.

Ginsburgh, V. (2005). Languages, genes, and cultures. Journal of Cultural Economics, 29(1), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10824-005-4074-7.

Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2007). The economics of the European Patent System. Oxford University Press: Oxford. 250 p.

Harhoff, D., Hoisl, K., Reichl, B., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2009a). Patent validation at the country level—the role of fees and translation costs. Research Policy, forthcoming.

Harhoff, D., Hoisl, K., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2009b). Languages, fees and the international scope of patenting in Europe. ECARES Working Paper, 2009-003.

Lazaridis, G., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2007). The rigour of EPO’s patentability criteria: An insight into the “induced withdrawals”. World Patent Information, 29(4), 317–326.

Mejer, M., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2009). Economic incongruities in the European patent system. ECARES Working Paper, 2009-016.

Roland Berger. (2005). The cost of the sample European patent – new estimates. www.3pod.cz/download/cost_analysis_2005_en[1].pdf. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Stevnsborg, N., & van Pottelsberghe de la, B. (2007). Patenting procedures and filing strategies. In D. Guellec & B. van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (Eds.), The economics of the European Patent System (pp. 155–183). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & François, D. (2009). The cost factor in patent systems. Journal of Industry. Trade Compet (forthcoming).

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & van Zeebroeck, N. (2008). A brief history of space and time: The scope-year index as a patent value indicator based on families and renewals. Scientometrics, 75(2), 319–338. doi:10.1007/s11192-007-1864-z.

van Zeebroeck N. (2007). Patents only live twice: A patent survival analysis in Europe. Université Libre de Bruxelles, Solvay Business School, CEB Working Papers, 07-028.RS.

van Zeebroeck, N., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & Guellec, D. (2009). Claiming more: The increased voluminosity of patent applications and its determinants. Research Policy, 38(6), 1006–1020.

Annual Reports

Canadian Intellectual Patent Office. Annual Report 2006–2007. www.cipo.ic.gc.ca/epic/site/cipointernet-internetopic.nsf/en/h_wr00094e.html. Accessed 1 May 2008.

European Patent Office. Annual Report 2006. www.epo.org/about-us/office/annual-reports/2006.html. Accessed 1 May 2008.

European Patent Office. Annual Report 2007. www.epo.org/about-us/office/annual-reports/2007.html. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Indian Patent Office. Annual Report 2005–2006. http://ipindia.gov.in/cgpdtm/AnnualReport_2005_2006.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Japan Patent Office. Annual Report 2007. www.jpo.go.jp/shiryou_e/toushin_e/kenkyukai_e/annual_report2007.htm. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Korean Intellectual Property Office. Annual Report: Overview and highlights of 2006. www.kipo.go.kr/kpo2/user.tdf. Accessed 1 May 2008.

State Intellectual Property Office of the Republic of China. Annual Report 2006. www.sipo.gov.cn/sipo_English/laws/annualreports/ndbg2006/. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Trilateral Cooperation. Trilateral Statistical Report 2006. www.trilateral.net/tsr/tsr_2006/. Accessed 1 May 2008.

United States Patent and Trademark Office. Performance and accountability report: Fiscal year 2007. www.uspto.gov/web/offices/com/annual/2007/index.html. Accessed 1 May 2008.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Marco Connor, Andrew Fielding, Stephen Gardner and Gaétan de Rassenfosse for their useful comments as well as to the participants of the CESifo Venice Summer Institute—Workshop Reforming Rules and Regulations, 18–19 July 2008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 and Figs. 6 and 7.

Relative cost saving of 10 years of protection due to the implementation of the London Agreement, May 2008 (in EUR). The cost savings are simulated for three configurations: before the LA, after the LA in its current format, with 15 member states (LA15); and (LA34), with all EPC contracting states having supposedly ratified the London Agreement. Procedural fees include the validation fees. EPO-3 includes Germany, Great Britain and France, which have all ratified the London Agreement. EPO-6 (or −13, or −34) stands for the patents validated in the 6 (or 13 or 34) most frequently targeted countries. Source: Based on own calculations: c.f. Table 8 in the Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., Mejer, M. The London Agreement and the cost of patenting in Europe. Eur J Law Econ 29, 211–237 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-009-9118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-009-9118-6