Abstract

Job satisfaction has long been discussed as an important factor determining individual behavior at work. To what extent this relationship is also evident in the teaching profession is especially relevant given the manifold job tasks and tremendous responsibility teachers bear for the development of their students. From a theoretical perspective, teachers’ job satisfaction should be negatively related to turnover intentions and absenteeism, and positively to high-quality teacher-student interactions (i.e., emotional support, classroom management, and instructional support), enhanced student motivation, and achievement. This research synthesis provides a comprehensive overview of the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and these variables. A systematic literature search yielded 105 records. Random-effects meta-analyses supported the theoretically postulated relationships between teachers’ job satisfaction and their turnover intentions, absenteeism, teacher-student interactions, and students’ outcomes. Effects were significant not only for teachers’ self-reports of their professional performance, but also for external reports. On the basis of the research synthesis, we discuss theoretical, conceptual, and methodological considerations that inform future research and prospective intervention approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Job satisfaction represents a key indicator of occupational well-being and has gained widespread interest in both research and practice as an important factor for predicting occupational behavior (Judge et al., 2001; Spector, 2022; Weiss, 2002; Wright et al., 2007). Across different occupational groups, job satisfaction is positively associated with general productivity, more satisfied recipients, a higher commitment to the job, and enhanced engagement (Judge et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2002; Whitman et al., 2010).

The question of whether teachers’ job satisfaction is, as in other occupational groups, crucial for their professional performance seems particularly important given the great responsibility teachers bear for the cognitive-motivational development of their students (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Matteucci et al., 2017; Tymms et al., 2018). At the same time, the teaching profession belongs to a professional group that faces high dropout rates, especially among those entering the profession (den Brok et al., 2017; Ingersoll, 2001), increasing teacher shortage worldwide (OECD, 2005; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2016), generally low occupational well-being (Iriarte Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020), and frequent incapacity to work due to mental and physical illness in the teaching profession (Seibt et al., 2009). Therefore, the urgent question arises as to which psychological characteristics might play a role in these phenomena. Studies across different occupational groups that show associations with reduced turnover intentions, attrition rates, and increased mental and physical health suggest that job satisfaction could be an answer to this question (Baker, 2004; Faragher et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2007). However, it is not self-evident that those results transfer to the teaching profession. Above all, general studies do not allow any conclusions about whether there are certain aspects of the teaching profession for which job satisfaction is particularly relevant.

Against this background, it seems particularly important to investigate the job satisfaction–performance link for the teaching profession and systematically review previous findings. Previous meta-analyses that refer specifically to the teaching profession suggest that job satisfaction might also be important for teachers and link it to general outcomes such as turnover intentions (Li & Yao, 2022; Madigan & Kim, 2021). In addition to general performance indicators (e.g., turnover intentions and absenteeism), examining clearly defined job requirements specific to the teaching profession, such as the quality of teacher-student interactions and students’ cognitive and motivational development, allows for a more differentiated insight into the specific areas of teachers’ work that benefit more or less from job satisfaction. Accordingly, the present meta-analysis aims to address this research gap and to summarize the various studies investigating the relationship between job satisfaction and specific performance outcomes in the teaching profession in addition to more general outcomes.

The Concept of Job Satisfaction

The concept of job satisfaction has been the subject of research for decades. It can be defined as an attitude towards the job resulting from a cognitive evaluation of specific job aspects (Spector, 2022; Weiss, 2002). In this sense, job satisfaction indicates what people think about their job (Spector, 2022), whether they perceive their needs to be satisfied at work (Dinham & Scott, 1998), and whether they experience a balance between rewards received and energy invested (Scarpello & Campell, 1983). As a cognitive evaluation of the work, job satisfaction is one of the domain-specific aspects of subjective well-being, which is divided into cognitive and affective experiences (Diener et al., 1999). Likewise, Weiss (2002) clearly distinguished the cognitive evaluation of job aspects from the emotional experiences and argued that both job satisfaction and affect are reciprocally related but distinct constructs (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Judge & Ilies, 2004).

In addition to the global evaluation of one’s own work, job satisfaction can be operationalized by satisfaction with specific aspects of one’s work (Spector, 2022). Different frameworks emphasize various facets, of which the following four have often been identified empirically (Lester, 1987; Spector, 2022): nature of work (e.g., satisfaction with work content and work itself), general context factors (e.g., satisfaction with leadership, supervision, and autonomy), rewards (e.g., satisfaction with recognition, pay, and promotion), and social aspects of the job (e.g., satisfaction with colleagues and cooperation).With regard to the teaching profession, initial evidence also points to the multidimensionality of job satisfaction, with the factors “nature of work” and “context” emerging most clearly (Dicke et al., 2019). The different satisfaction facets correlate moderately with each other as well as with global measures of job satisfaction (Highhouse & Becker, 1993; Spector, 2022). Accordingly, it is reasonable to consider both global job satisfaction and specific facets separately because they are not congruent (Bowling & Hammond, 2008; Spector, 2022).

Whether general or facet-specific, job satisfaction is not only discussed in the context of individuals’ mental and physical health (Benevene et al., 2018; Faragher et al., 2013; Simone et al., 2016), but also as an important predictor of general performance and success in the workplace (Diener, 2012; Judge et al., 2001).

Job Satisfaction and Professional Performance: Theoretical Considerations

Theoretical ideas describe different psychological processes through which job satisfaction could be related to individual behavior at work. These processes are summarized in the affective-events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), which distinguishes two pathways explaining the link between job satisfaction and professional performance, one involving cognition-driven behavior and the other mediated through affect-driven behavior (Weiss, 2002). The assumption underlying cognition-driven behavior postulates that attitudes, such as job satisfaction, determine behavioral tendencies, which result in behavioral consequences such as approach or avoidance behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). For instance, job satisfaction likely leads to the desire to maintain the positively evaluated situation in contrast to thoughts about leaving the job or frequent absenteeism (Siegrist, 2002; Weiss, 2002). This experience facilitates more autonomous forms of motivation and enhances the ability to direct, regulate, and energize individual behavior (Kumari et al., 2021), likely resulting in higher engagement and further investment of individual resources.

In addition to the cognitive pathway, job satisfaction can also influence behavior mediated by affective experiences (Weiss, 2002; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). This assumes that job satisfaction is associated with positive affective experiences (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Judge & Ilies, 2004; Weiss, 2002; Wright et al., 2007). Positive affect, in turn, potentially increases an individual’s thought-action repertoire and strengthens personal resources (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Scherer & Moors, 2019). As a result, basic cognitive processes, such as problem solving or executive functioning, are enhanced, which, in turn, translates into individual behavior and professional performance (Eysenck & Calvo, 1992; Forjan et al., 2020).

Empirical research suggests that job satisfaction is associated with a variety of behaviors in the professional context, linking it to general productivity and performance at work, lower turnover intentions, and higher work attendance across different occupational groups, because general job satisfaction not only enhances prosocial behaviors, work engagement, and commitment to the job, but is also associated with reduced health problems and negatively related to somatic symptoms, such as sleeping problems, headaches, and tachycardia (Benevene et al., 2018; Simone et al., 2016; Tett & Meyer, 1993; Whitman et al., 2010). For this reason, satisfied teachers should be less likely to think about leaving their job. Likewise, these teachers should be less likely to be absent, not only because job satisfaction is associated with reduced health problems, but also because satisfied teachers are less likely to stay home with minimal health complaints. Against this background, the question of how strong the relationship between job satisfaction and professional performance is in the teaching profession and for which aspects of teachers’ professional performance it is most decisive seems particularly compelling.

Job Satisfaction and Professional Performance in the Teaching Profession

The following explains what we mean by professional performance and what aspects can be distinguished in the various job tasks of teachers.

Defining Teachers’ Professional Performance

In general, turnover intentions and absenteeism represent relevant indicators of professional performance across occupational groups. After all, a cognitive withdrawal from work and frequent sick-leaves impede successful performance of job tasks. In the teaching profession, the most important job tasks include creating effective learning environments through supportive teacher-student interactions, increasing student motivation, and facilitating successful student learning (Bardach & Klassen, 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Zee & Koomen, 2016).

Various conceptual approaches describe emotional support, classroom management, and instructional support as key dimensions of teacher-student interactions (Hamre et al., 2013; Kunter & Voss, 2013; Praetorius et al., 2018). Emotional support indicates the generation of a supportive learning environment by the teachers that acknowledges students’ academic, social, and emotional needs (Strati et al., 2017). By contrast, effective classroom management is needed to maximize instructional learning time through the proactive management of classroom disruptions and the establishment of behavioral rules and routines (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008). Lastly, instructional support describes the facilitation of student interest, motivation, and higher-order thinking through a variety of teaching strategies (Pianta et al., 2012; Scherer et al., 2016). Empirical research suggests that these three dimensions are central for both students’ motivation and achievement, which can be defined as follows (Allen et al., 2013; Bosman et al., 2018; Downer et al., 2010; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

Student motivation is described as the central force that drives specific actions, decisions, and intensity of behavior. Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and expectancy-value theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) are among the most influential psychological theories on motivation and help define this comprehensive construct. According to these theories, the experience of autonomy (e.g., self-efficacy) and competence (e.g., self-concept) are central determinants of students’ expectancy to successfully accomplish a task and, consequently, of students’ behavioral engagement in learning activities. Furthermore, the value students attach to their tasks, whether they perform them out of inherent interest and enjoyment (i.e., autonomous motivation) or for external incentives and to avoid punishment (i.e., controlled motivation), is seen as a relevant part of students’ motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Intrinsic motivation is related to learning goals, promotes academic engagement, and manifests itself in interest, all of which reflect motivational constructs (Howard et al., 2021; Spinath & Steinmayr, 2012). Therefore, we considered all of these variables as indicators of students’ motivation in our meta-analysis.

Student achievement is closely related to students’ motivation (Howard et al., 2021) and indicates the extent to which instructional strategies and learning activities have been successful in enhancing students’ knowledge, understanding, and skills. Students’ achievement is often assessed by grades, test scores, or general teacher appraisals.

Linking Teachers’ Job Satisfaction to Their Professional Performance

Arguably, job satisfaction is also positively related to the effective completion of the various job tasks in the teaching profession, as has been suggested for general performance measures in different occupational groups (Meyer et al., 2002; Tett & Meyer, 1993; Whitman et al., 2010). The prosocial classroom model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009) provides a teaching-specific rationale and suggests that teachers’ well-being determines the quality of teacher-student interactions, which, in turn, are perceived by their students and thus affect students’ motivation and achievement.

Accordingly, job satisfaction should result in more effective teacher-student interactions. Satisfied teachers are thought to invest more resources (e.g., time and effort) in both lesson planning and implementation (Granziera & Perera, 2019; Siegrist, 2002) and are more effective at problem solving and managing unexpected situations due to an enhanced thought-action repertoire (Burić & Moè, 2020; Forjan et al., 2020; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). Cognitive capacities are not used on negative thoughts such as turnover intentions. This should, on the one hand, be apparent in more effective classroom management. On the other hand, enhanced cognitive processes should enable teachers to create cognitively activating and engaging lessons and to respond to student questions more flexibly. Likewise, the positive affect associated with job satisfaction facilitates social interactions (Forgas, 2002; Frenzel et al., 2021). Hence, teachers might have more cognitive and emotional resources available to show empathy, care, and sensitivity for students’ needs (Isen, 2001; Nezlek et al., 2001). Additionally, satisfied teachers show more enthusiasm while teaching (Burić & Moè, 2020), which is, on the one hand, positively associated with emotional support, classroom management, and instructional support (Kunter et al., 2008; Lazarides et al., 2021) and, on the other hand, likely facilitates students’ motivation and achievement through both students’ experience of autonomy and competence (Allen et al., 2013; Moè & Katz, 2020; Ruzek et al., 2016) and emotional contagion (Frenzel et al., 2021; Hatfield et al., 1993). Lastly, teachers’ job satisfaction likely impacts students’ learning through reduced absenteeism (Miller et al., 2008).

Complementing the assumptions outlined above, established theoretical models suggest that the constructs under consideration are reciprocally related (Frenzel et al., 2021; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Judge et al., 2001). Accordingly, teachers who experience success in accomplishing work tasks as indicated by both students’ motivation and achievement and positive teacher-student interactions in class are more likely to be satisfied with their work (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Judge et al., 2001). For instance, it might be easier to provide effective teaching with motivated and high-performing students, which, in turn, could foster teachers’ job satisfaction (Frenzel et al., 2021; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

The Role of Specific Facets of Job Satisfaction in Teacher Performance

As outlined above, job satisfaction can be classified into four overarching dimensions (Spector, 2022), that is, nature of work (e.g., satisfaction with teaching, student accomplishment, student behavior, and working with students), social aspects (e.g., collegial support, supervision, communication, and cooperation), general context factors (e.g., satisfaction with school management, operating procedures, school environment, amount of administrative work, autonomy, and professional development), and rewards (e.g., pay, fringe benefits, contingents rewards, and promotion). The distinction between different facets of job satisfaction is important with regard to the assumption that they might be differentially associated with teachers’ professional performance. For instance, in evaluating their professional situation, teachers might place particular emphasis on one specific facet of the job, which, in turn, might particularly influence their professional performance.

Central reasons why teachers choose their profession include the variety of social interactions (e.g., with students, colleagues, and parents) and the responsibility for the social-emotional development of students in addition to the mission of teaching and knowledge transfer (Watt et al., 2012). This is also reflected in teachers’ professional goals because establishing positive teacher-student relationships and contributing to student learning seem increasingly important in this profession (Butler, 2012). Hence, aspects regarding the nature of work (e.g., teacher-student relationship, interactions, and students’ learning achievements) may play a major role in teachers’ evaluation of their job. The resulting satisfaction with teaching-related aspects, in turn, might be particularly relevant for their professional performance.

The Present Review

Job satisfaction is an important aspect of teachers’ occupational well-being. Additionally, job satisfaction could be an important factor in reducing teacher attrition and absenteeism, promoting high-quality teacher-student interactions and thus obtaining positive student development. Thus, teachers’ job satisfaction might not only be critical for the individual’s health and well-being (Simone et al., 2016), but also for student development (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). The present research synthesis is the first to provide a comprehensive overview of prior research on the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and professional performance, both generally, in terms of turnover intentions and absenteeism, and profession-specific, with regard to the quality of teacher-student interactions and students’ motivation and achievement. By considering this broad set of variables, we go beyond previous research syntheses that were either based on a more general conceptualization of well-being (i.e., several well-being indicators combined into one variable) and did not allow for a differentiated investigation of job satisfaction and its facets, or considered only general outcomes such as turnover intentions (Bardach et al., 2022; Madigan & Kim, 2021; Maricuțoiu et al., 2023).

In addition to summarizing what we can learn from prior research, our goal was to uncover areas with insufficient evidence and discuss where more research is needed to obtain a more nuanced understanding of the potentially complex relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and their performance and to approach the question of which specific facets of teachers’ job satisfaction are especially important for teachers’ performance. Having a reliable basis from which to draw general conclusions is particularly important for different stakeholders in the teaching profession to assess the importance of promoting teachers’ job satisfaction.

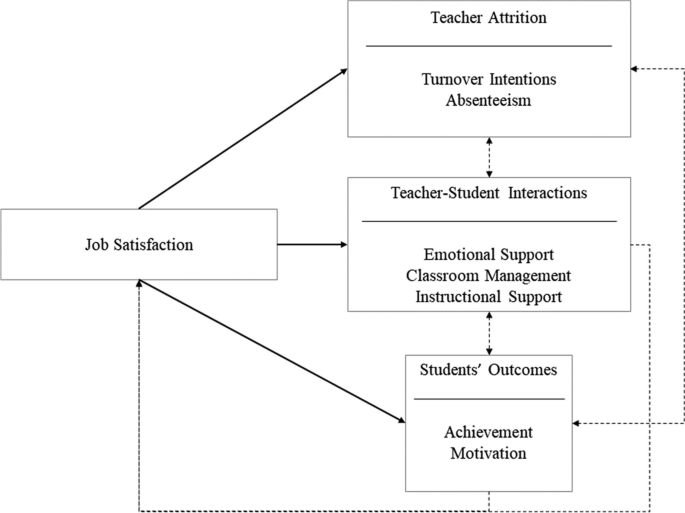

The heuristic working model (Fig. 1), which is based on the theoretical assumptions outlined above, summarizes the hypothesized relationships between teachers’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions, absenteeism, quality of teacher-student interactions, and students’ educational development. Accordingly, we expected teachers’ job satisfaction to correlate negatively with their turnover intentions and absenteeism while assuming a positive relationship with the quality of teacher-student interactions because general job satisfaction should enhance teachers occupational commitment, engagement, and the investment of individual resources (Granziera & Perera, 2019; Siegrist, 2002), as well as expand the thought-action repertoire (Burić & Moè, 2020; Forjan et al., 2020; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005).

Ultimately, teachers’ job satisfaction likely relates to students’ academic development through high-quality teacher-student interactions (Allen et al., 2013; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), the transfer of positive affect in class (Hatfield et al., 1993), and less teacher absenteeism. However, as students’ motivation and achievement are more distal to teachers’ well-being, less pronounced relationships are expected for these variables (Bardach & Klassen, 2021).

Second, we also hypothesized stronger effects for satisfaction with the nature of work compared to other facets of job satisfaction (i.e., context factors, rewards, and relationship with colleagues) because interacting with students and contributing to students’ development represent important reasons for teachers’ career choices and professional goals (Butler, 2012; Watt et al., 2012).

Third, we examined study and sample characteristics that could explain the expected variability of effect sizes between studies. Because the use of self-reported questionnaires alone carries the risk of inflated observed correlations due to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012), we examined whether significant correlations could also be found for other sources of reports. For instance, teachers’ current affectivity might influence both their recall of experiences, such as their general satisfaction experienced during the last school year, and the recall of information on the outcome, such as the number of days absent, or the occurrence of negative teacher-student interactions (Tourangeau, 2000). Accordingly, teachers’ self-reports are likely to lead to an overestimation of the relationships as they are based on shared variance rather than on true relationships. We further controlled for teachers’ gender, years of teaching experience, and grade level taught. Empirical evidence suggests that these sample characteristics account for different experiences of job satisfaction and influence the development of the observed performance outcomes (Ettekal & Shi, 2020; Scherrer & Preckel, 2019; Toropova et al., 2021).

Lastly, we also reviewed longitudinal studies to verify whether effects are evident across different time spans and to provide an insight into the stability of job satisfaction and its reciprocity with professional performance. Longitudinal studies are thought to be a more appropriate approach to the question of causality than cross-sectional studies. However, smaller effect sizes are expected; on the one hand, because of the time interval between the assessment of the constructs under consideration and, on the other hand, because of controlling for the baseline levels of the criterion to predict changes in the criterion. This likely reduces the size of the relationship because a lot of variance can already be explained by the stability of the construct (e.g., predicting students’ end-of-year grade with teachers’ job satisfaction at the beginning of the school year while controlling for students’ baseline achievement).

Method

Literature Search

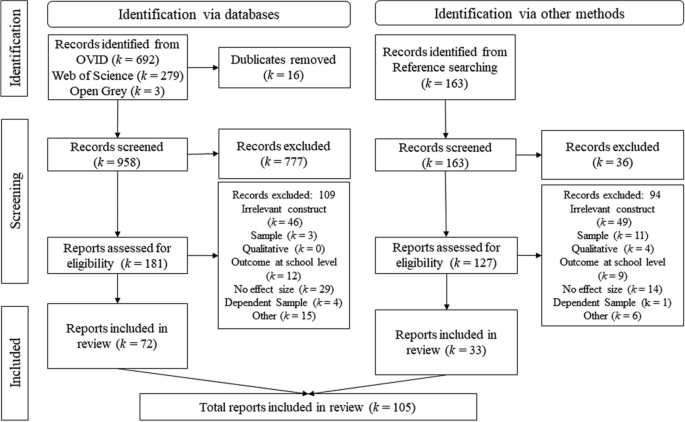

We conducted a systematic literature search in November 2020 and updated the search in December 2022 (Fig. 2). We initially searched the databases PsycINFO, Web of Science, and OpenGrey to identify both published and unpublished work on teachers’ job satisfaction. For the literature search conducted in PsycINFO, we combined the thesaurus search terms for teacher with the thesaurus terms for job satisfaction leaving the outcomes of interest out in the first step to obtain a comprehensive literature review and avoid studies that only incidentally reported the association between teachers’ job satisfaction and their professional performance from not appearing in our literature search. This search had 692 results. Subsequently, we confined the search in Web of Science by including the outcome variables of interest using a combination of related terms with the following constructs: job satisfaction, absenteeism, turnover intentions, teacher-student interactions, emotional support, classroom management, instructional support, students’ achievement, and students’ motivation. This resulted in 279 additional records after removing duplicates. We conducted an additional search in OpenGrey to search specifically for unpublished work, theses, and dissertations. This revealed three additional records. The detailed search terms and strategies that we implemented in the different databases are listed in the Online Supplement (Table S1). Among other aspects, we searched titles, abstracts, and keywords for the specified terms.

In addition to the database searches we reviewed the reference lists of the identified studies as well as previous meta-analyses that investigated similar relationships for relevant titles (Bardach et al., 2022; Madigan & Kim, 2021; Maricuțoiu et al., 2023). We also searched the titles citing the identified studies. In total, the backward search, citation search, and review of previous meta-analyses identified 163 new records.

Inclusion Criteria

With the support of three student research assistants, the first and second authors screened titles and abstracts of the records identified by the aforementioned search strategies. All coders successfully completed training based on the coding manual prior to the prescreening. We included studies for the subsequent full-text coding, that (1) assessed teachers’ job satisfaction, (2) reported on turnover intentions, absenteeism, teacher-student interactions, or students’ motivation and achievement, (3) investigated a sample of teachers currently teaching at pre-, elementary, or secondary schools, (4) reported quantitative data, and (5) were written in a language with a Latin alphabet. We implemented these inclusion criteria rather liberally and considered studies for full-text coding where it was not apparent from the title and abstract whether they would fulfill the criteria to minimize the risk of erroneously excluding relevant studies. Nevertheless, 813 studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded based on the screening of title and abstracts, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Page et al., 2021) in Fig. 2. We applied the following refined inclusion and exclusion criteria in the subsequent full-text coding.

Criteria Regarding Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

We included both studies measuring job satisfaction across a variety of established instruments (e.g., Job Satisfaction Scale, Warr et al., 1979; Teacher Job Satisfaction Questionnaire, Lester, 1987) and studies using self-designed items (e.g., “Overall, how satisfied are you with teaching as a job?”). Studies measuring general positive affect (e.g., “When I’m at work, I feel pretty happy.”) or career optimism (e.g., “I get excited when I think about my teaching career.”) were excluded from the analysis. Studies were also excluded if they operationalized job satisfaction with one item that asked only about teachers’ career decisions (e.g., “Would you choose teaching again?”) because this item is conceptually close to intention to stay. Likewise, scales confounding job satisfaction with other aspects, such as self-efficacy, turnover intentions, or job characteristics, were excluded (e.g., Mogilevsky, 2019).

Criteria Regarding Teachers’ Occupational Performance

We included studies that assessed teachers’ professional performance via teachers’ self-reports as well as via student ratings, classroom observations, principal reports, and school records.

With regard to teacher-student interactions, we excluded studies using scales that asked teachers to appraise their own abilities, such as scales on teachers’ self-efficacy or teachers’ educational beliefs and attitudes (e.g., Vidić & Miljković, 2019) because the mindset about one’s own abilities does not necessarily translate into actual behavior. In contrast, we considered both scales that captured teachers’ interaction behavior (e.g., being sensitive for students’ individual problems, anticipating student misbehavior, and providing cognitively challenging tasks) and scales that depict student behaviors as an indicator of the quality of teacher-student interactions (e.g., approaching the teacher with questions or individual problems, and frequency of disruptive or off-task behavior).

Additionally, we included a category for general teacher-student interactions to include scales combining different aspects and thus impeding a clear assignment to the categories of emotional support, classroom management, or instructional support.

Because we focused on turnover intentions, we did not consider studies that investigated actual turnover (e.g., Cha & Cohen-Vogel, 2011). On the one hand, we decided to target cognitive withdrawal in contrast to behavioral withdrawal because of the paucity of studies that did not only investigate post-hoc assessments of teachers who had already left the teaching profession. On the other hand, turnover intentions are discussed as the most likely valid predictor of actual turnover (Ajzen, 1991; Wong & Cheng, 2020).

Generally, we excluded studies that measured the dependent variable at the school level (e.g., Dicke et al., 2019). Such measures preclude an unambiguous assignment of the outcome to the specific teacher. Studies reporting on students’ misbehavior in class were included in the analysis because the presence or absence of students’ behavioral problems in class can be categorized as an indicator of classroom management (Pianta et al., 2012).

Criteria Regarding Teacher Sample

Because we were interested in teachers currently teaching at general pre-, elementary, middle, or high schools, we excluded studies that surveyed preservice, special education, university, or college teachers. Those contexts are not readily comparable to general school contexts (Bettini et al., 2019) and could thus reduce the comparability of the samples. Similarly, samples of principals and administrative school staff were excluded from the meta-analyses because these professional groups are less involved in interactions with students. However, if a mixed sample comprised more than 50% general preschool, elementary, middle school, or high school teachers, studies were included in the analysis.

Criteria Regarding Effect Sizes

We included studies that reported either correlation coefficients or other statistics that can be converted to correlation coefficients, such as statistics for mean differences (Thalheimer & Cook, 2002). We also considered longitudinal studies or intervention studies. Of the longitudinal studies, we only included cross-sectional effect sizes in the meta-analyses and additionally reviewed longitudinal effect sizes systematically. For intervention studies, we only drew on effect sizes from the baseline measurement or the control group to exclude the possibility of biased correlations based on intervention effects. Studies that did not report the bivariate correlation coefficients and, for example, only reported results from multiple regression analyses or from structural equation models were excluded from the meta-analyses because these analyses control for a variety of covariates that differ between studies, which can change the interpretation of effect sizes. In these cases, we contacted the authors of the respective studies to ask for the correlation coefficients. Of the 58 authors contacted via email for this purpose, 15 provided the requested coefficients. Still, 43 studies had to be excluded because the requested correlation coefficients could not be obtained.

A total of 105 studies were included in the research synthesis based on the more refined criteria, thus excluding a further 203 records after full-text coding. Figure 2 provides a detailed overview of the reasons for why studies were excluded.

For the meta-analyses, three additional studies were excluded because they only reported longitudinal effect sizes. One additional study was excluded because it only measured on specific job satisfaction facet (i.e., pay satisfaction), which is too specific to indicate general job satisfaction. However, these studies were considered in the systematic review of longitudinal and facet-specific research.

Agreement between coders on deciding whether to include or exclude a study after full-text coding was κ = 0.82, based on double coding of 92 studies (30% of total studies coded). Any discrepancies in the decisions about inclusion or exclusion were resolved through discussion. An overview and references of included studies are available in the Online Supplement (Tables S2 and S3).

Coding

The first and second authors independently conducted the aforementioned full-text coding of primary studies. We retrieved central study characteristics (i.e., authors, publication year, publication type, journal, design, and response rate), sample characteristics (i.e., sample size, country, percentage of female teachers, mean age, mean teaching experience, subject taught, grade level taught, student composition, and mean class size), and information on the investigated variables (i.e., type of construct, instrument used, number of items, response scale, rater perspective [i.e., self-reports vs. other], mean, standard deviation, and reliability). For a detailed overview of the definition and operationalization of constructs considered as correlates of teachers’ job satisfaction, see Table S4 in the Online Supplement. Additionally, the following information was coded for the effect size: type of effect size (e.g., correlation, and mean difference), level of significance, information on whether manifest or latent effect sizes were retrieved, and source of the effect size (i.e., reported in article, requested from authors, and calculated based on primary data).

Regarding the classification of the dependent variables into the associated coding category (i.e., turnover intentions, absenteeism, emotional support, classroom management, instructional support, general interaction, student motivation, and student achievement), the agreement between coders was κ = 0.92 based on the double coding of 35% of the included studies (k = 35). To verify the reliability of the coding process, either the first or second author or a trained student research assistant double-coded studies depending on who had conducted the preliminary coding. Any discrepancies in coding decisions were resolved through discussion. The data are available open access at PsychArchives (https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.13691).

Data Processing

We were interested in the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and professional performance. For most effect sizes included, we directly extracted and coded the respective correlation coefficients. Only two studies reported mean differences (Lambert et al., 2012; Patrick, 2007), which we converted to correlation coefficients (Borenstein et al., 2009a; Thalheimer & Cook, 2002). Afterwards, we recoded effect sizes for the sake of interpretability so that positive correlations indicated that higher job satisfaction was associated with higher professional performance. Although most studies reported manifest effect sizes, six studies reported latent correlations. In order to increase the comparability of effect sizes, we estimated the uncorrected correlation for these studies following the formula of Hunter and Schmidt (2004, p. 96). Furthermore, we considered dependencies that emerged in the data of the primary studies before meta-analytic aggregation of effect sizes. Including multiple effect sizes based on the same sample might bias standard errors and distort the overall results of a meta-analysis (Borenstein et al., 2009b; Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). Three types of dependencies existed in primary studies: dependent effect sizes due to multiple subsamples reporting on one association, dependent effect sizes due to the application of multiple subscales and dependent effects due to the use of self-reports and other reports of the observed constructs within one sample. We did the following to deal with these dependencies. First, when studies included multiple reports of the same relationship based on dependent subsamples, we considered only the effect size from the largest subsample. Second, if articles reported more than one effect size for each association because they used multiple subscales for the same construct, we calculated the correlation for the corresponding composite score, following the recommendations of Hunter and Schmidt (2004, pp. 435–439). This approach not simply averages effect sizes within studies but makes it possible to correctly estimate composite effect sizes based on the number of different subscales, the covariance of constructs from different subscales, and the dependent effect sizes. Third, because we were interested in potential differences in the effect sizes that were due to the rater perspective, we did not aggregate self-reports and other reports. This concerned one study (Stahl Lerang et al., 2021). Although the error in the aggregated effect sizes is reasonably small if the number of effect sizes that are based on the same sample is minor compared to the total number of effect sizes included in the synthesis (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004), we applied robust variance estimation to address the dependencies in sampling errors within this study (Hedges et al., 2010).

Analyses

Following the preparation of effect sizes, we conducted univariate meta-analyses for each performance outcome for which at least five primary studies were available (Higgins et al., 2009). We specified random-effects models because of the expected variability of effect sizes between studies. We applied the Hunter-Schmidt estimator for heterogeneity in all analyses with untransformed correlation coefficients using the R package metafor (Field, 2001; Viechtbauer, 2010). Additionally, we conducted psychometric meta-analyses with artifact distributions using the R package psychmeta to account for the impact of measurement error on the effect sizes (Dahlke & Wiernik, 2021; see also Hunter & Schmidt, 2004).

We systematically reviewed studies that assessed individual job satisfaction facets to explore the question of whether different facets of job satisfaction are especially closely associated with specific performance outcomes in the teaching profession. Due to the paucity of studies that measured job satisfaction on a facet-specific basis, we only calculated univariate meta-analyses for the association between different job satisfaction facets (i.e., satisfaction with nature of work, relationships with colleagues, and context factors) and turnover intentions (k ≥ 5).

The total amount of heterogeneity was estimated based on τ2, which represents an absolute measure of heterogeneity between studies (Borenstein et al., 2017). We also computed the Q-test for heterogeneity and the relative proportion of variance in the effect sizes that can be attributed to between-study differences with the I2 statistic (Borenstein et al., 2017). We ran meta-regression models using the R package metafor (Field, 2001; Viechtbauer, 2010) to examine potential moderators possibly explaining heterogeneity in effect sizes between studies. The following study and sample characteristics were considered in the meta-regression models: publication year, type of publication, teachers’ gender, years of teaching experience, grade level (i.e., elementary, secondary, and mixed), and the rater perspective (i.e., self-reports or other). Continuous moderators were entered directly into meta-regression models while categorical moderators were dummy-coded for these analyses. We considered moderators in separate meta-regression models and did not include them simultaneously because the number of studies with complete information on all moderators would be too small for the analysis. In addition to meta-regression models, we conducted subgroup analyses to further explore the differences between teacher self-reports and external reports for teacher-student interactions.

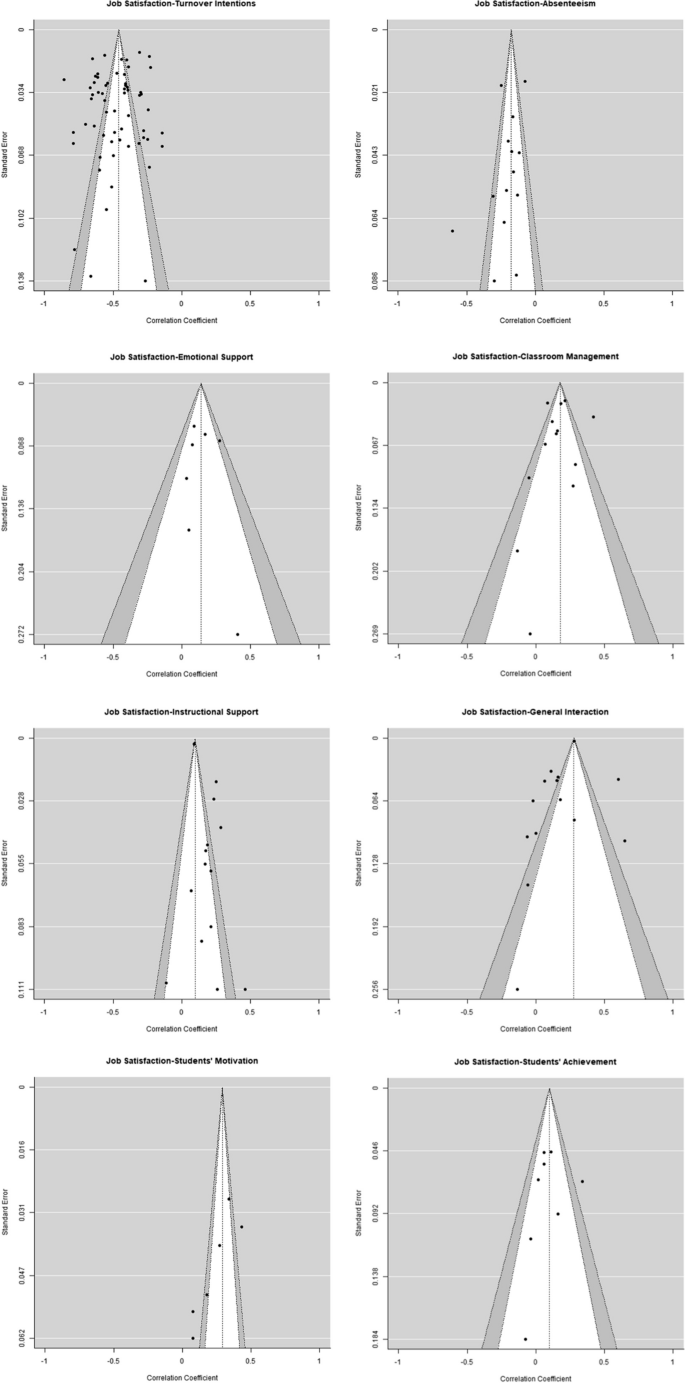

To consider the possibility of biased estimates of the average effect size (Carter et al., 2019), we investigated potential publication bias visually using funnel plots and statistically by conducting Egger’s regression tests and computing precision-adjusted effects sizes (Egger et al., 1997).

Except for considering measurement error (through psychometric meta-analyses) and publication bias, we did not assess any other risk of bias, such as the risk of bias in the studies included with standardized risk-of-bias tools. Risk of bias is undoubtedly an important issue (Higgins et al., 2019). While approaches to the assessment of risk of bias are well established in meta-analyses of randomized and nonrandomized trials (Sterne et al., 2019), there are currently no clear recommendations on how to assess risk of bias in correlational studies. Therefore, we decided to reveal potential sources of risk of bias with the help of meta-regression analyses and to investigate whether effect sizes differed as a function of the study and sample characteristics. With the exception of the risk-of-bias assessment, the research synthesis adhered to the PRISMA checklist (Page et al., 2021).

Results

Study and Sample Characteristics

Although we specifically searched for unpublished work, the vast majority of the 101 studies included in the meta-analyses represented published journal articles (k = 78). However, 23 studies were either un- or informally published, including two master theses, one book chapter and 20 dissertations. Studies were published between 1973 and 2022 (Md. = 2015). Most studies were conducted in the United States (k = 39), followed by Norway (k = 7) and Canada (k = 7). Six studies were conducted in China, four in Germany and Spain respectively, and three studies each in Belgium, Ghana, Israel, New Zealand, and Spain.

Overall, the 101 studies included in the meta-analysis were based on a total sample size of 323,035 teachers, varying from 14 to 154,959 teachers per sample. However, excluding two studies with an extremely large sample size of 104,358 and 154,959 teachers (Bellibaş et al., 2020; Blömeke et al., 2021) left a total sample size of 63,718, ranging between 14 and 4,208 teachers per study. The percentage of female teachers ranged between 13.3% and 100.0% with an average of 70% female teachers per sample. The overall mean teaching experience was 11.75 years (SD = 5.28), with a minimum of less than one year and a maximum of more than 22 years of teaching experience. The data set contained 14 studies conducted in primary schools, 33 studies with secondary school teachers, and 47 studies based on mixed grade levels.

Most of the studies measured general job satisfaction. Only 15 studies considered different facets of job satisfaction. Moreover, most studies used self-designed items to measure job satisfaction, with 17 studies using single-item scales (e.g., “Overall, how satisfied are you with teaching as a job?”). The validated instruments that were used most frequently included the Job Satisfaction Scale (k = 4; Warr et al., 1979), the Job Diagnostic Survey (k = 4; Hackman & Oldham, 1975), the Teacher Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (k = 3; Lester, 1987), and the Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale (k = 3; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011).

Overall Effects

We examined the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and professional performance separately for each outcome of interest (Table 1). Forest plots are provided in the Online Supplement (Figs. 1–8). While 61 studies reported on teachers’ turnover intentions, only 14 studies investigated the relationship with absenteeism. Regarding teacher-student interactions, most studies considered instructional support (k = 14), general teacher-student interactions (k = 14), and classroom management (k = 13), while only seven studies assessed emotional support. Associations with students’ achievement (k = 8) and motivation (k = 6) were also rarely studied.

As hypothesized, results indicated a significant negative association of teachers’ job satisfaction with both turnover intentions (r = − 0.46, CIr = [–0.52, –0.40]) and absenteeism (r = − 0.18, CIr = [–0.25, –0.10]). These results suggest that teachers who are generally satisfied with their job are, on average, less likely to consider changing their job and absent less frequently, according to both their self-reports and school records.

Overall, the relationships between teacher job satisfaction and teacher-student interactions were small but positive, with a correlation of r = 0.14, CIr = [0.08, 0.20] for emotional support, r = 0.18, CIr = [0.10, 0.25] for classroom management, r = 0.10, CIr = [0.05, 0.15] for instructional support, and r = 0.28, CIr = [0.21, 0.35] for general teacher-student interaction. Accordingly, teachers who are satisfied with their job seem more effective in establishing caring, structured, and cognitively activating learning environments, as measured by teacher self-report, student ratings, classroom observations, and principal evaluation.

The findings regarding the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and students’ motivation also indicated a positive relationship between the two (r = 0.29, CIr = [0.18, 0.40]). Accordingly, teachers who are generally satisfied with their job perceive their students as more motivated. Students of satisfied teachers also experienced greater satisfaction of their basic psychological needs and reported being engaged in school more actively. Similarly, a positive relationship also emerged for students’ achievement (r = 0.10, CIr = [0.02, 0.17]), indicating that students taught by satisfied teachers were more successful in achieving their learning goals in terms of school grades, test scores, and general teacher evaluation.

In general, the psychometric meta-analyses substantively confirmed the results described above. Overall, correlations corrected for measurement error tended to be somewhat larger, but similar in size, with negative relationships between teachers job satisfaction and turnover intentions (radj = − 0.59, CIradj = [− 0.65, − 0.54]), absenteeism (radj = − 0.21, CIradj = [− 0.27, − 0.14]), and positive relationships with emotional support (radj = 0.18, CIradj = [0.08, 0.29]), classroom management (radj = 0.22, CIradj = [0.15, 0.29]), instructional support (radj = 0.14, CIradj = [0.12, 0.17]), general interactions (radj = 0.33, CIradj = [0.30, 0.36]), students’ motivation (radj = 0.37, CIradj = [0.20, 0.54]), and students’ achievement (radj = 0.12, CIradj = [0.01, 0.23]).

Relations between Specific Facets of Job Satisfaction and Professional Performance

A total of 14 studies examined specific facets of teachers’ job satisfaction. Overall, the number of studies that considered facet-specific relationships was usually too low to conduct meta-analyses (k < 5). The only exception to this was the association between different job satisfaction facets (i.e., satisfaction with nature of work, relationships with colleagues, and context factors) and turnover intentions (Table 2). An overview of the relationship between specific job satisfaction facets and the remaining performance outcomes is provided in the Online Supplement (Table S5).

For the job satisfaction facets nature of work (k = 7, r = − 0.34, CI = [− 0.53, − 0.15]), relationship with colleagues (k = 6, r = − 0.32, CI = [− 0.53, − 0.12]), and context factors (k = 5, r = − 0.36, CI = [− 0.41, − 0.31]), the meta-analytic relationships with turnover intentions were moderate and comparable in size. Similar patterns of results emerged for satisfaction with pay and benefits. Regarding the remaining performance outcomes, a few isolated relationships were only reported for satisfaction with colleagues and context factors, providing very little empirical evidence to identify patterns of results.

Heterogeneity and Moderating Effects

There was substantial heterogeneity in effect sizes between studies (Table 1), except for the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and emotional support. The few studies that examined emotional support were quite similar with regard to the conceptualization, which might explain the small heterogeneity between studies. The greatest total amount of variability among the true effects was observed for turnover intentions (τ2 = 0.023) and students’ motivation (τ2 = 0.012). For most relationships, a moderate to large proportion of the total variability (I2 = 46.06 – 96.19) could be attributed to the true variance of effect sizes between studies (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Against this background, we investigated study and sample characteristics that might explain heterogeneity (Table 3). Generally, the meta-regression results should be interpreted with caution as some analyses were based on a very small number of effect sizes.

Study Characteristics

Results from meta-regression analyses revealed a significant increase in effect size over time for the relationship between job satisfaction and general teacher-student interactions (β = 0.01, p < 0.001) and a significant decrease in effect size over time for the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intentions, suggesting publication year as a significant moderator. Additionally, stronger effect sizes were found in meta-regression analyses for published (vs. unpublished) studies for associations between teachers’ job satisfaction and both instructional support (β = 0.18, p = 0.005) and general teacher-student interactions (β = 0.09, p = 0.001).

From a methodological perspective, we investigated whether effect sizes varied as a function of the rater perspective (teacher self-reports vs. external reports). The rater perspective was a significant moderator of the relationships between teachers’ job satisfaction and absenteeism, general teacher-student interactions (β = 0.16, p < 0.001), and students’ motivation (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). Effect sizes were significantly larger when absenteeism was estimated based on school records (k = 2, r = − 0.37, CIr = [− 0.47, − 0.26]) as compared to teachers’ retrospective self-reports (k = 12, r = − 0.17, CIr = [− 0.22, − 0.13]). For general teacher-student interaction, the effect sizes were significantly larger when they were based on self-reports (k = 7, r = 0.25, CIr = [0.21, 0.29]) as compared with reports by students or external observers (k = 7, r = 0.14, CIr = [0.08, 0.19]). The same was true for students’ motivation, where the effect sizes were also larger for teachers’ self-reports (k = 2, r = 0.35, CIr = [0.29, 0.41]) than for reports by others (k = 6, r = 0.12, CIrother = [0.04, 0.19]). However, in either case, the correlations were positive and statistically significant regardless of how they were assessed. Detailed results of subgroup analyses and the separate effect sizes for self-reports and external reports can be found in Figures S10–S13 in the Online Supplement.

Sample Characteristics

Results suggested that the relationships between teachers’ job satisfaction and both instructional support (QM = 14.68, p = 0.001) and general teacher-student interactions (QM = 50.94, p < 0.001) varied depending on the grade level taught. The relationships with general teacher-student interactions were weaker in primary school samples (β = − 0.37, p < 0.001) compared to mixed samples. Larger effect sizes emerged in secondary school samples (β = 0.09, p = 0.001) compared to mixed samples for instructional support, while smaller effect sizes were found in secondary school samples (β = 0.09, p = 0.001) compared to mixed samples for general teacher-student interactions. A closer look revealed that studies based on mixed grade levels relied solely on teacher self-reports, as well as studies conducted in secondary schools assessing instructional support. In contrast, barely any study conducted in primary schools used teacher self-reports, instead using classroom observations, student reports, or principal ratings. Additionally, the meta-regression results revealed that the size of the correlation between job satisfaction and general teacher-student interactions varied as a function of the proportion of female teachers in the sample; a smaller correlation was found for samples with a higher proportion of female teachers (β = − 0.01, p < 0.001). However, the proportion of female teachers was higher in primary schools compared to secondary schools or mixed samples. As a result, studies with a higher proportion of female teachers were also more likely to apply more objective measures (i.e., classroom observations, student reports, and principal ratings) for the quality of general teacher-student interactions. Finally, teaching experience emerged as a significant moderator for the relationships with turnover intentions (β = 0.01, p = 0.047), general teacher-student interactions (β = 0.01, p = 0.035), and students’ motivation (β = − 0.01, p = 0.025).

Relations between Teachers’ Job Satisfaction and Professional Performance over Time

The literature search identified 16 longitudinal studies of which nine reported longitudinal effect sizes for the relationship between job satisfaction and performance among teachers, including eight studies that implemented two measurement points with a mean time interval of 349.62 days (SD = 209.61, range = 152–730) and one study that involved three measurement points with a time interval of 152 days. All studies reported longitudinal correlations or regression coefficients between job satisfaction at the prior measurement point and the corresponding performance outcome at the subsequent measurement point without controlling for the baseline level of the performance outcome. In summary, these longitudinal correlations, though smaller, appear to confirm the effects found for turnover intentions and students’ motivation but not for absenteeism, quality of teacher-student interactions, and students’ achievement (a more detailed overview is depicted in Table S6 in the Online Supplement). These simple longitudinal correlations can be taken as a first approximation of the longitudinal nature of the relationship and provide insights into whether effects are evident across different time spans. However, longitudinal correlations obtained without controlling for prior levels of the outcome variable cannot be used to meaningfully estimate direct effects of job satisfaction. Likewise, primary studies did not provide any insights into reciprocal relationships.

Publication Bias

First, graphical exploration of funnel plots (Fig. 3) suggested the possibility of publication bias for some relationships, as the plots did not appear to be fully symmetrical (Sterne et al., 2005), with a lack of small studies with small effects that trended toward zero. Results of Egger’s regression tests for funnel plot asymmetry (Table 4) confirmed this impression, yielding significant results for instructional support (β = 2.34, p < 0.001), general teacher-student interactions (β = − 1.69, p = 0.008), and students’ motivation (β = − 9.08, p < 0.001). Other than that, there was no evidence of publication bias. Precision-adjusted effect size estimates are reported in Table 4, which were comparable or even larger than the estimates from the meta-analyses. Though Egger’s regression tests do not provide a strong indication of publication bias, results regarding the three doubtful relationships should be interpreted with caution especially as the publication status explained variability in effect sizes for instructional support and general teacher-student interactions.

Discussion

Despite the great relevance of job satisfaction that is evident across different occupational groups (Judge et al., 2001; Spector, 2022), job satisfaction receives little attention in teacher-specific theoretical models explaining teachers’ professional performance. This research synthesis is the first to integrate the empirical evidence on the link between job satisfaction and professional performance for teaching-specific performance outcomes that also considers different facets of teachers’ job satisfaction and includes longitudinal evidence.

The Job Satisfaction–Performance Link in the Teaching Profession — Main Findings and Avenues for Future Research

Overall, the findings from our research synthesis verified the theoretically postulated association between job satisfaction and professional performance, which has been demonstrated across different occupation groups, also for teaching-specific performance outcomes (Judge et al., 2001; Li & Yao, 2022; Madigan & Kim, 2021; Meyer et al., 2002; Tett & Meyer, 1993; Whitman et al., 2010). More specifically, results suggest that satisfied teachers report lower turnover intentions and are less likely to be absent. In turn, satisfied teachers seem more effective in establishing positive teacher-student interactions and caring, structured, and activating learning environments, as perceived by teachers and others (i.e., students, principals, and external observers). Likewise, students of satisfied teachers are more likely to show higher motivation and achievement. However, the association between teachers’ job satisfaction and students’ achievement was small. This can be attributed to several reasons. First, achievement is the most distal outcome in the hypothesized process (Bardach & Klassen, 2021). Therefore, smaller effect sizes are expected. Second, the effect on achievement tends to be smaller for subjects other than math (Authors, 2022; Nye et al., 2004). Yet, different subjects were combined in the analyses. In summary, most of the observed correlations are rather small in size and only partly moderate.

Does Job Satisfaction Represent a Relevant Psychological Characteristic?

One main research objective is to identify relevant psychological characteristics that are related to teachers’ professional performance, especially to the quality of teacher-student interactions and students’ academic development. Compared to other disciplines, the role of job satisfaction in determining job performance seems less salient in educational psychology, where established theories primarily saw cognitive abilities and knowledge or stable personality traits as central (for an overview of these traditions see Kunter et al., 2013).

The correlations found in our research synthesis are comparable in size to effects found in meta-analyses that examined other psychological characteristics in the context of teachers’ professional performance, which further emphasizes that job satisfaction seems to play a significant role alongside other characteristics. Significant associations were also found in meta-analyses for teachers’ personality (Kim et al., 2019), professional knowledge (D’Agostino & Powers, 2009), and self-efficacy (Kim & Seo, 2018; Klassen & Tze, 2014; Zee & Koomen, 2016). These syntheses found comparable effect sizes for the general evaluation of teaching, teacher-student interactions, and classroom processes, but somewhat smaller effect sizes for students’ achievement compared to results from our meta-analyses. In contrast, teachers’ cognitive (e.g., intelligence and basic skills) and verbal abilities seemed unrelated to the quality of teacher-student interactions and students’ educational outcomes (Aloe & Becker, 2009; Bardach & Klassen, 2020). Although comparable effect sizes were obtained for different psychological characteristics, previous research did not investigate the relative importance of job satisfaction in the context of other characteristics. To further address the question of whether job satisfaction has an effect beyond other psychological characteristics, future research should consider various characteristics simultaneously (Caprara et al., 2006; Pekrun, 2021; Wright & Bonett, 2007).

The longitudinal studies included in our research synthesis provide preliminary insights into the longitudinal nature of the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and subsequent professional performance and suggest that effects are evident across different time spans. Future research should implement longitudinal or experimental studies more frequently to further investigate the nature of the link between job satisfaction and professional performance in the teaching profession. For this purpose, longitudinal studies should capture both job satisfaction and performance outcomes at multiple time points and control for baseline levels of the considered constructs (for an illustration of such a design see Benita et al., 2018; Dicke et al., 2015). A longitudinal observation over one school year would be ideal with regard to teacher-student interactions and students’ characteristics. It is more difficult to interpret the results, for instance, if teachers change the classes they teach after one school year. In contrast, a longer time period would be appropriate for longitudinal studies targeting turnover because teachers might not immediately consider changing their profession if they do not experience their work to be satisfying in the short term (as, e.g., in Voss et al., 2023). Intervention studies implementing a randomized controlled design would make it possible to investigate whether enhancing teachers’ job satisfaction also leads to improved teacher-student interactions or enhanced educational outcomes for students (for examples of studies investigating other teaching characteristics see Dicke et al., 2015; Jennings et al., 2013).

Despite the open questions, the correlations found in our meta-analyses, while small to moderate, are both comparable in size to effects of other psychological characteristics and evident across different time spans suggesting that job satisfaction represents a relevant characteristic.

Under Which Conditions is the Job Satisfaction–Performance Link Most Pronounced?

Previous research provides limited information on whether the partially small effect sizes found in our meta-analyses might be larger for certain subgroups. Identifying sample characteristics under which the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and their performance is particularly close is especially important to further understand theoretical mechanisms underlying the association and to identify who benefits most from the association (Gill, 2021). Meta-regression analyses suggested no differences in effect size depending on teacher sample characteristics because all differences seemed attributable to a specific methodological moderator, namely, the rater perspective, which emerged as an important source of possible bias in primary studies. Smaller correlations also remained significant for external reports of teachers’ instructional support and general teacher-student interactions, emphasizing the relevance of these results. For instance, drawing on teacher self-reports to measure both job satisfaction and indicators of professional performance has the risk of obtaining effect sizes that are too large due to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Teachers who are generally satisfied with their job might be more likely to recall positive events when asked about their turnover intentions, absences, classroom interactions, or experiences with students (Tourangeau, 2000). Accordingly, valid conclusions about the relationships can only be derived if teachers’ professional performance is either assessed through more objective measures (e.g., school records, actual turnover, or standardized tests) or reported through other sources (e.g., students, colleagues, classroom observations, or principals). This allows an assessment of the extent to which job satisfaction elicits changes in teachers’ professional behavior also perceived by others, as evident in our findings. Therefore, future studies are encouraged to combine teachers’ self-reports with other perspectives more frequently.

Although results from meta-regression analyses suggest that effect sizes are robust across different samples and that the satisfaction of all teachers, regardless of their demographic characteristics should be addressed equally, further psychological characteristics remain of particular interest. Investigating the interplay between job satisfaction and other psychological characteristics, such as self-efficacy, personality, professional competence, or other well-being characteristics, would provide insights into the relative importance of job satisfaction for teachers’ professional performance and investigate whether different psychological characteristics have an additive, buffering, or conflicting effect. Although the effect sizes found in our meta-analyses are partially small, job satisfaction might still be relevant because it interacts with other characteristics (e.g., positive affectivity). For instance, future studies should target the questions of whether teachers might be satisfied despite experiencing high demands and exhaustion and whether job satisfaction can counteract the negative effects of burnout for teachers’ professional performance (e.g., studies investigating the interaction between different psychological characteristics of teachers; see Braun et al., 2022; Seiz et al., 2015).

Lastly, the question remains as to which students can benefit most from the association. In particular, the class composition (e.g., class size and number of students with learning disabilities or social-emotional demands) and students’ background variables (e.g., socio-economic status, migration, and ethnicity) seem relevant characteristics determining the size of the relationship because the teacher generally plays a more important role in the development of students with less favorable manifestations of these variables (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Klusmann et al., 2016). Arguably, whether teachers are more or less satisfied and highly effective in creating a positive learning environment and providing individualized support makes a critical difference, particularly for the development of students at risk of failing school (Sirin, 2005). Unfortunately, we were unable to include these student characteristics in the meta-regression analyses due to insufficient data. Future studies should therefore consider additional moderators (e.g., student characteristics) to further explore the question of for whom and under which conditions the job satisfaction–performance link is most pronounced.

Are Specific Job Satisfaction Facets Especially Important?

Interacting with students and contributing to students’ learning and development are important reasons why teachers choose the profession and largely determine teachers’ professional goals. Therefore, these aspects might be particularly crucial for teachers’ evaluation of their job (i.e., their job satisfaction) and, in turn, for their professional performance. Only few studies measured job satisfaction regarding different facets of the job considering the theoretically postulated multidimensionality of the construct. While differentiating between facets may not be as important in demonstrating an effect of job satisfaction because teachers think of the aspect of their job most important to them when they report on their overall job satisfaction, using multidimensional instruments assessing satisfaction with specific aspects of the teaching profession would provide a better understanding of the differential effects that satisfaction with specific facets may have on similar outcomes. This research synthesis offers a first insight into this question: Contrary to our expectations, no differential findings emerged for specific facets of teachers’ job satisfaction. Satisfaction with different aspects of the job (i.e., nature of work, relationships with colleagues, and context factors) seem equally important, at least in relation to turnover intentions. Due to the small number of studies investigating absenteeism, the quality of teacher-student interactions, and students’ outcomes in the context of specific job satisfaction facets, no meaningful conclusions about differential effects can be drawn for these outcomes.

Consequently, future research should measure job satisfaction as a multidimensional construct to allow a more differentiated view on which job satisfaction facets (i.e., which characteristics of the teaching profession) are most significant for the association with teachers’ professional performance (Dicke et al., 2019). This would not only facilitate a more targeted approach to promoting teachers’ satisfaction but it would also open up the debate about whether raising teacher salaries is a useful means to keep teachers in the profession or improve teaching.

Limitations

The present research synthesis offers a comprehensive summary of previous studies on teachers’ job satisfaction and reviews relevant evidence on the job satisfaction–performance link for the teaching profession. However, our research synthesis is not without limitations that must be considered when interpreting these results.

First, we cannot rule out the possibility that unpublished papers, which we could not find via our literature search, would reveal a different pattern of results. We attempted to mitigate the influence of publication bias by specifically searching for unpublished work (i.e., Open Grey), considering theses, dissertations, and book chapters. However, a visual investigation of the funnel plots and results of Egger’s regression tests for funnel plot asymmetry indicated a possible influence of publication bias for instructional support, general teacher-student interactions, and students’ motivation (Sterne et al., 2005). Additionally, stronger effect sizes were found in meta-regression analyses for published (vs. unpublished) studies for these associations. Although precision-adjusted effect sizes tended to be comparable in size, future work could attempt to further address the limitations of publication bias by requesting unpublished analyses from authors in the respective field of research.

Second, one major challenge of job satisfaction research is the conceptualization of the construct, both theoretically and empirically. A considerable number of studies included in the meta-analyses used single-item measures and or self-constructed scales, although job satisfaction is a long-studied construct for which various validated instruments exist. This makes it difficult to assess the validity and comparability of constructs across studies, although single-item measures are moderately correlated with established satisfaction scales (Wanous et al., 1997). Several studies claiming to measure job satisfaction had to be excluded from the meta-analyses because related but distinct constructs such as enthusiasm, stress, career choice, or a description of job characteristics were merged into the scale (e.g., Johnson et al., 2012).

Third, the operationalization methods for the performance outcomes used in the studies included in our meta-analyses differed not only in the rater perspective and type of measure but also in the underlying conceptualization, which entails the risk of limited comparability between studies and potential bias. Turnover intentions were mostly operationalized as cognitive withdrawal from work, although some studies asked about the intention to remain in the profession (reverse coded). Due to the small number of studies assessing actual turnover, we were unable to include turnover as an outcome. However, having more studies prospectively examining actual turnover behavior would be interesting (e.g., Cha & Cohen-Vogel, 2011; Grissom, 2011). Like turnover intentions, the vast majority of studies measured absenteeism by retrospective teachers’ self-reports, differing greatly in the time period queried and the categorization of response scales. In contrast, some studies determined the number of days absent by surveying school records. The use of these more objective measures would be desirable for future research. With regard to the quality of teacher-student interactions, studies included in the meta-analyses considered both teacher practices and student behavior as indicators of classroom management. Due to the small number of studies, it was not possible to further differentiate between students’ outcomes. For this reason, different motivational constructs were included to determine the effect size for students’ motivation (i.e., engagement, basic need satisfaction, and self-concept). Likewise, students’ achievement was summarized across different subjects (i.e., reading and math), although the subject might account for variability in effect sizes (Klusmann et al., 2022; Nye et al., 2004). Consequently, it is not certain if all studies synthesized measured the same underlying construct. This is also illustrated by the remaining heterogeneity that could not be explained by the considered moderators. Although it would be desirable for future meta-analyses to focus on more comparable effect sizes, our research synthesis provides preliminary evidence for the relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and a variety of teacher-specific performance outcomes.

Fourth, no causal inferences can be made based on findings from our meta-analyses because we focused on cross-sectional effect sizes for reasons of comparability. Established theoretical models suggest that job satisfaction is likely part of a complex system with bidirectional relationships to performance indicators (Frenzel et al., 2021; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Judge et al., 2001). For example, when teachers have a sense of accomplishment in completing their tasks, it likely increases their job satisfaction (Burić & Moè, 2020; Judge et al., 2001). This idea is also discussed in the literature, which suggests that positive interactions with students, highly motivated students who actively participate in class, and high student achievement may enhance teachers’ well-being (Ruiter et al., 2020; Spilt et al., 2011). Unfortunately, there is no empirical evidence providing insights into the reciprocity of the relationships. Additionally, shared third variables (e.g., school leadership and teachers’ self-efficacy) influencing both teachers’ job satisfaction and instructional quality (Bellibaş et al., 2020; Caprara et al., 2006) could underly the correlative pattern of results. As previously addressed, the task of future research is to further investigate the issue of causality or reciprocity through longitudinal or experimental designs that consider possible third-party variables.

Finally, in addition to the univariate associations established in the present research synthesis, a model-based meta-analysis (e.g., metaSEM) represents a promising approach to further investigate the psychological processes through which teachers’ professional well-being affects their performance in establishing effective learning environments and fostering student social-motivational and cognitive development (Becker & Aloe, 2019). This approach makes it possible to fit mediation models on a pool of correlation matrices (Cheung, 2020). However, due to the paucity of suitable primary studies, we were not able to test the theoretically hypothesized mediation process between teachers’ job satisfaction, teacher-student interactions, and students’ outcomes meta-analytically (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

Nonetheless, our research synthesis represents a comprehensive overview of research on the relationship between job satisfaction and both general and teaching-specific professional performance, including a large proportion of studies not directly interested in the relationship. This makes our research synthesis particularly valuable because it provides an overview of studies from different lines of research not readily found in a basic literature search, thus offering initial insights into the nature of the relationship and the basis for theoretical, conceptual, and methodological considerations informing future research and practice.

Practical Considerations

In light of the importance that teachers’ job satisfaction appears to have for their professional performance, it might be promising to further develop and establish interventions that aim to promote teachers’ job satisfaction. Given the effects on the diverse aspects of their professional performance found in our meta-analyses, job satisfaction seems an important characteristic of teachers’ professional well-being, especially for the central tasks of teaching: creating effective learning environments and supporting students in their cognitive and motivational development. Interventions that aim to improve teachers’ working conditions appear promising, as satisfaction results from cognitive evaluation of these aspects (Spector, 2022; Weiss, 2002). Current research suggests that the school environment (e.g., principal leadership, cooperation with colleagues, school climate, and students’ composition) plays a particularly important role in teachers’ job satisfaction (Cansoy, 2018; Toropova et al., 2021). For instance, a reduction of teachers’ workload, that is, reducing working hours and focusing on time spent teaching, slightly increased teachers’ job satisfaction (Butt et al., 2005). At the same time, collaboration with and support from colleagues could also reduce the workload. This might be achieved by targeting school leadership and school climate (Berger et al., 2022).