Abstract

Recent technological advances in the field of genomics offer conservation managers and practitioners new tools to explore for conservation applications. Many of these tools are well developed and used by other life science fields, while others are still in development. Considering these technological possibilities, choosing the right tool(s) from the toolbox is crucial and can pose a challenging task. With this in mind, we strive to inspire, inform and illuminate managers and practitioners on how conservation efforts can benefit from the current genomic and biotechnological revolution. With inspirational case studies we show how new technologies can help resolve some of the main conservation challenges, while also informing how implementable the different technologies are. We here focus specifically on small population management, highlight the potential for genetic rescue, and discuss the opportunities in the field of gene editing to help with adaptation to changing environments. In addition, we delineate potential applications of gene drives for controlling invasive species. We illuminate that the genomic toolbox offers added benefit to conservation efforts, but also comes with limitations for the use of these novel emerging techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite ongoing activities to halt biodiversity loss, we are still losing many species at an alarming rate (Turvey and Crees 2019; WWF 2020). Targets to stop this loss, defined by the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) to be achieved by 2020, have clearly not been met (CBD 2020). Currently the post-2020 targets for CBD are developed and the EU biodiversity strategy discussed, both phrasing ambitious goals and milestones. However, it is less clear how these could be achieved. Meanwhile, conservationists seek to identify tools to improve and solve many of the conservation challenges globally, such as managing small populations or controlling invasive species. At the same time a technological revolution is taking place in the field of molecular biology, granting novel opportunities to screen, manipulate and even edit genomic material. These technological advancements have been seen as opportunities for conservation by some (Breed et al. 2019; Hohenlohe et al. 2021), and highly controversial among others (e.g. see motion 75 of the IUCN World Conservation Congress 2020 on synthetic biology https://www.iucncongress2020.org/motion/075). While the field of synthetic biology (see glossary) has been a centre of debate (Piaggio et al. 2017), conservation projects can benefit from the existing knowledge in other areas of biotechnology such as animal or plant breeding approaches applied in agriculture and livestock (McLean-Rodríguez et al. 2021).

With this perspective, we aim to provide an overview on the latest biotechnological developments for conservation practitioners and managers and especially highlight their feasibility for present and future potential conservation applications. This manuscript is a result of a G-BiKE COST Action (https://g-bikegenetics.eu ) workshop on novel genomic tools for conservation. The aim of the workshop was to bring practitioners and researchers together and help bridging the gap between researchers and managers, which has been described earlier (Shafer et al. 2015). Most attendees of the workshop had a background in animal conservation, thus our overview is likely to be biased towards animals, but we state that many topics are similar also for plants and other organisms.

Here, we focus on four important conservation areas: (1) management of small populations, (2) restoring and increasing genetic diversity, (3) support of adaptation to changing environments, and (4) invasive species management. We discuss the underlying techniques of genomic screening, cloning, gene editing and gene drive, highlighting examples from different plant and animal species. We also provide some key questions which need to be asked before starting a conservation project (Fig. 1 and end of each section) and present an overview on the feasibility and challenges of those techniques for the different conservation areas (Fig. 2). With this overview, we hope to inspire, inform and illuminate if and how these technologies can be used by managers and practitioners in their conservation projects.

Genomic and biotechnological toolkit for conservation. Main conservation problems (left side, each box marked with a different colour) and most relevant questions when starting a genomic study. The flow chart connects conservation problems with techniques already available or under development. Arrow colours link the technologies with the conservation tasks (the same colour is used for the arrows as in the boxes on the left)

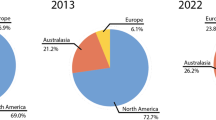

Feasibility of conservation areas and the different genomic and biotechnological tools. Each line and colour presents one of the main conservation problems (same colours as in Fig. 1). The timeline indicates the feasibility of the listed tools for current and future potential conservation applications

Small population management using genomic tools

Small population management is a critical tool to safeguard populations and has evolved at a rapid pace over the last decades, as a response to the escalating biodiversity crisis (see also CBD 2020, Target 12). Many populations have become so small and fragmented that they are vulnerable to genetic and demographic stochasticity and unable to recover on their own, even when the anthropogenic threats they face can be successfully mitigated (Gilpin and Soulé 1986). Due to their limited (effective) population size, small populations lose genetic diversity over time, and as such adaptive potential, making them prone to inbreeding. In these situations, effective conservation requires a strategy that incorporates the most appropriate population management activities, selected from a range of options across ex situ and in situ conditions (Traylor-Holzer et al. 2019). Whether ex situ or in situ, the work follows a multi-step procedure starting from identifying the need and defining the role of the management actions, setting measurable goals, evaluating alternative (genetic) management actions and methods, monitoring progress towards the set genetic goals and adjust as needed (see the IUCN guidelines on ex situ management https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/44952 and Westgate et al. 2013, McGowan et al. 2017). Genomics now has the potential to revolutionise how we approach these steps (Russello and Jensen 2018; Supple and Shapiro 2018) by evaluating the genetic history and status of the in situ and any ex situ populations in more detail.

Defining ex situ populations and their relationship to in situ populations using genomics

Today, ex situ conservation programs often rely completely or in part on existing collections of living individuals, gametes, plant seeds, or tissue and blood samples. Genomic techniques allow us to detect DNA sequence variation at single nucleotides (i.e. single-nucleotide polymorphism: SNP, see glossary) that can be used to evaluate the effects of historic founder selection (Gomes Viana et al. 2018; Frandsen et al 2020; Ogden et al. 2020; Wei and Jiang 2021) and set guidance on how to increase levels of genetic diversity and minimise genetic similarity (Bragg et al. 2020) via selective addition of unrepresented lines (Wildt et al. 2019; Galla et al. 2020; Miller et al. 2010). The efficiency of ex situ management partly relies on the profound knowledge of a species’ taxonomic status and recent demographic history. For many species of conservation concern, such information is either missing or incomplete, and genomics has proven key in filling knowledge gaps (e.g. Frandsen et al. 2020; Robinson et al. 2021a) and delineating management units (Barbosa et al. 2018) starting from almost any type of sample (e.g. museum collections and biobanks; Baveja et al. 2020). Likewise, the inclusion of species specific genomic analysis generates unseen possibilities to reach predefined long-term conservation goals whether that is to e.g. increase genetic diversity or minimize inbreeding, even if little is known about relatedness of individuals. Genome wide SNP data are starting to be used to complement or even replace missing or incomplete pedigrees to provide robust data for guiding breeding efforts (Galla et al. 2020). Simultaneously, genomic data will guide optimal management (e.g. balancing hybridisation or the potential of adaptation) with the in situ population as a benchmark. As such, modern population management can and should foster a tight link between conservation efforts of ex situ populations and their wild counterparts (Boscari et al. 2021) and be integrated into the overall conservation strategy for a single or multiple species (the One Plan Approach coined by the Conservation Planning Specialist Group of the IUCN; Pritchard et al. 2012; Byers et al. 2013).

Small in situ populations, either remnant or reintroduced, are affected by the same negative processes that affect ex situ populations (e.g. loss of genetic diversity and accumulation of inbreeding), so the same general principles used for genetic management in the latter could be applied in the former. These include the maximization of founder population size and the management of gene flow; however, managing precise breeding is often out of reach. The same applies to ex situ management of group living species such as many aquatic species, some primate species or hoof stock living in large herds, where individual pedigrees are unknown and breeding recommendations are difficult. For plants, seed banks, i.e. storage of seeds, is the most popular way of ex situ conservation due to ease of storage, low costs and low risks of infestation or predation (Schoen and Brown 2001). However, seed banking can be problematic for species with low seed longevity, persistent dormancy or low germination rates. For these species, living collections for example in botanical gardens are often implemented as ex situ method. In addition to the same negative genetic processes of small and isolated in situ populations, ex situ living collections of plants risk local adaptation to non-natural, ‘garden’ conditions. To minimize the risk of adaptation to non-natural conditions, ‘quasi in situ’ conservation—ex situ collections that are grown in natural environments—can be suggested as a compromise between ex situ and in situ conservation (Volis and Blecher 2010). In combination with genomic techniques to monitor genetic variation in next generations this may provide a successful integrated conservation strategy for plants.

Improving population management and monitoring through genomics

Minimizing overall genetic relatedness within populations (i.e. pedigree based kinship breeding) significantly reduces the pace at which diversity is lost and became the method of choice to manage small populations (Lacy et al. 2012; Che-Castaldo et al. 2021). Out of necessity, the pedigree approach was built on assumptions such as no founder relatedness and the absence of selection, knowing that this is not always the case (Frankham 2008; Hogg et al. 2019). Hence, many breeding programs will benefit from genetic screenings to (i) compensate for differences between theoretical and realized kinships (Grueber et al. 2021), (ii) resolve origin and screening for hybridisation (Howard-McCombe et al. 2021), (iii) detect clonal reproduction (e.g. many plants and apomictic species (Brown and Marshall 1995), (iv) guide reproduction or translocations in species for which individual record keeping, and as such pedigree reconstruction and/or kinship estimation, is (historically) missing, inaccurate or difficult e.g. group managed species (McLennan et al. 2020), (v) optimize health via direct screening for genetic or heritable diseases e.g. Devil Facial Tumor Disease (Storfer et al. 2018; Hohenlohe et al. 2019) or maintaining overall immunity (Savage and Zamudio 2011) and (vi) ensure that the genetic diversity captured within the ex situ populations represents that of the in situ population (Kleinman-Ruiz et al. 2019; Wei and Jiang 2021). Given the existing similarity of the general management aims in plant and animal ex situ collections, botanic gardens could benefit by adapting and broadly using the well-established scientific approaches by the zoo community (Fant et al. 2016; Wood et al. 2020).

Genomic tools as drivers for future management and biobanking

The largest gain in genomic analyses, over more traditional genetic tools, is their power to get additional information on genomic regions under selection, [e.g. runs of homozygosity (ROH) and deleterious mutations, Hohenlohe et al. 2021; see also Fig. 3 and glossary]. These could be introgressed genomic segments stemming from hybridisation or the lack hereof, or parts of the genome that are under selection. Additionally, population structure within a population can be detected and, depending on the conservation goals, should or could lead to a population management in separate groups based on evolutionary and genomic divergence. The genomic revolution also allows for direct identification of desirable genes and alleles, as well as the transfer of these adaptive genes to deliver new varieties, as has been proven effective for crop and livestock improvement (Wambugu et al. 2018). In addition, management of ex situ collections of plant genetic resources can benefit from genome-wide screening and the availability of reference-genome assemblies for almost all major crop species, overcoming the reproducibility issues related to earlier markers (Mascher et al. 2019).

Broad applicability of genomics to improve conservation management is, however, often limited by a lack of samples from current populations and their (wild) founders. Biobanking techniques are well suited for animals and plants (Heywood and Iriondo 2003), including seed banks, in vitro storage (slow growth and cryopreservation), pollen banks, tissue cryopreservation, DNA storage, and botanic gardens living collections (Thormann et al. 2006). As such, regional zoo and aquarium biobanks [e.g. the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) Biobank] and seed banking initiatives (e.g. Millenium Seed Bank) are very valuable for both research and population management by maintaining genetic diversity (e.g. Howell et al. 2021) or even reviving lost genetic lineages. The addition of genomic information, e.g. SNP genotypes, to the information linked to records of stored samples could complement and correct traditional metadata and constitute a molecular fingerprint (Digital Sequence Information (DSI), for more background and discussion see the White Paper on DSI at https://www.dsmz.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Collection_allg/Final_WiLDSI_White_Paper_Oct7_2020.pdf). Such a unique fingerprint would complement the conventional sample banks with bio-digital resource centres combining the storage of the preserved materials with their genomic and molecular characterization. Alongside improving the management of the collections, the dense genotyping information for all accessions would highlight duplicates and sampling coverage gaps (Mascher et al. 2019). Some novel initiatives within this context (e.g. the DivSeek project https://divseekintl.org), and the potential of genomics-based technologies, could generate a paradigm shift in the usability of bio- and cryobank collections and bridge the gap between different data types.

Questions to be considered for managing small populations

For some (mostly iconic) species, genomic data already provided useful insights to guide ex situ population management. While the list of species that can benefit from genomic screenings increases, the shortage of available resources, such as reference genomes and samples from both ex situ and in situ populations, is often hindering the evaluation of how current levels of genetic diversity compares to historic or current in situ diversity.

-

Which genomic tools will help secure the data needed (e.g. coding, non-coding, whole genome to scan for inbreeding levels and adaptive potential) to answer the management questions in an in- and ex situ framework?

Several populations and research questions have been or are currently generating data on wild plants and animals that potentially could be used to help improve population management. However, one of the challenges to overcome is how to integrate and allow comparisons among data collected over different time periods or geographic ranges with various technologies.

-

How can we ensure that different data types can be integrated and comparisons with suitable reference populations be made?

As more data isn’t always better and the data required might be very much case by base dependent;

-

What is the ideal amount of data (e.g. number of SNPs) needed to answer questions that are challenging a conservation breeding program over time, e.g. high mean kinship within a population requires an increased need for informative SNPs?

Depending on the conservation question(s) to be answered, the population size, management strategy and resources, it is important to consider sampling;

-

How many and which extant populations and/or individuals as well as historical collections need to be sampled to provide answers that can help guide the conservation action?

And explore if samples are linked to metadata;

-

Is demographic, medical or other relevant data linked to samples/individuals through databases (e.g. Zoological Information Management System (ZIMS) or BGCI PlantSearch), which could be used to better understand a given population?

And lastly, how can future considerations and needs be incorporated into a species management plan;

-

Will cryopreservation of cell lines or gametes be of future use?

Box A

Box B

Box C

Utilizing biotechnology developed on domestic species to conservation of wildlife

Genomic research on domestic animals has paved the way for the study of their wild relatives. These studies have applications for both ex situ and in situ population management. For example, in domestic species different breeds can become admixed over time and ancestral breeds lost. Genomic information can assist in the design of breeding programmes aimed at recovering original genetic variability from currently admixed breeds (Amador et al. 2014; Fernández et al. 2016). Such approaches have been useful in the conservation of domestic populations and, particularly, local breeds (Kristensen et al. 2015), but have the potential to support conservation efforts of wildlife as well (Hedrick 2010; Miller et al. 2017). For example, wild (Felis silvestris silvestris) and domestic (Felis silvestris catus) cats interbreed in Portugal (Oliveira et al. 2008), wild and domestic pigs (both Sus scrofa) interbreed on the Iberian Peninsula (Gama et al. 2013) and cultivated walnut populations mix with native walnut trees (Hoban et al. 2012). In each case, the domestic population threatens the wild population with genetic swamping. While identifying hybrids has been possible already with microsatellites or SNPs (e.g. Soto et al. 2003) new genomic resources could help to identify hybrid individuals and to distinguish between past and recent hybridisation events in previously unknown accuracy (Mattucci et al. 2019). Additionally simulations can be useful for predicting outcomes of hybrid gene flow (e.g. DiFazio et al. 2012). This has been shown to be especially relevant for estimating gene flow from transgenic plants and crops into their wild relatives.

Research into domestic animals has also allowed the development of tools and baseline knowledge, as exemplified by the large number of studies on wolves (Canis lupus) genomics, which take advantage of resources developed for dogs (e.g. Pendleton et al. 2018). These tools have allowed, for example, the identification of the origin of the black pigmentation of some American wolves as a result of ancient hybridization with dogs (Anderson et al. 2009), the identification of genes associated with altitude adaptation in central Asian wolves (Zhang et al. 2014) or the characterization of inbreeding at Isle Royale (Robinson et al. 2019).

Importantly, the management of domestic populations has also allowed the advancement of reproductive schemes and approaches that could also be applied to wild species. These involve the design of mating strategies that minimize inbreeding or maximize allelic diversity (Fernández et al. 2016; López-Cortegano et al. 2019) applicable to closely monitored and managed wild and captive populations. Similarly, research on domestic species enabled the development of assisted reproductive technologies allowing the introduction of allelic variants from one population to another without the need to move individuals, and even allowing the recovery of genetic variants from long-dead individuals (for examples see Table 1). Biomedical research that advances biotechnology also utilizes domestic species such as the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo), horse, and sheep, and these models have paved the way for reproductive technologies, such as cloning of wild counterparts like the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przwalski) and mouflon (Ovis aries musimon) (see references in Sandler et al. 2021, Box C and Table 1). These genomic and reproductive biotechnological advances in domestic species may also be combined in the future to design genomes with an increased variation, or that display more fit phenotypes (see Sect. “Facilitating adaptation to changing environments through biotechnological applications” for details). However, the strict selection of animal or plant breeding specimen for particular traits comes at the price of an additional reduction in the size of the founding population, with accompanying reduction in the effective population size (Amador et al. 2014; Toro et al. 2014; Fernández et al. 2016). Selective breeding of admixed populations can only aspire to restore the variation that is still segregating, but part of the original variation may no longer be available. In these cases, it may be possible to use cryopreserved biological material or seed banks to reintroduce some of the lost genetic variants into the population (Table 1).

A potentially new source of information derived from studies of biomedical models of domestic species, comes from studies on epigenetic variation. Epigenetics refers to changes in the gene products and ultimately phenotypes of individuals that are heritable but not associated with changes in the nucleic acid sequence. Rapid adaptations to changing environments can be brought by epigenetic mechanisms. Epigenetic modifications represent an extra-molecular component of biodiversity that links genomes to the environment, and ultimately improves the identification of conservation units by estimating the adaptive potential of organisms (Rey et al. 2020). Epigenetics has been put forward as a biomarker for physical conditions, and methylation levels that cells use to control gene expression might be of importance for guarding against the expression of harmful alleles under specific conditions (Marin et al. 2020). In plants, DNA methylation has been shown to regulate multiple processes, such as gene expression, genome stability and gene imprinting (Zhang et al. 2018; Gallego-Bartolomé 2020) and is postulated to play an important role in phenotypic plasticity and fast responses to sudden environmental changes (Colicchio and Herman 2020). Ultimately epigenetics may be valuable to the conservation practitioner as a new tool to delimit evolutionary significant units that take into account the capacity for organisms to adapt to rapidly changing environments (Rey et al. 2020).

When might domestic animals be good surrogate models for conservation of wildlife counterparts?

Domestic species, particularly those used for agriculture or biomedicine, are frequently well-studied and have genomic and reproductive science resources that are on the cutting edge of technology. When those domestic model species are congeners and closely related to species of concern, they can be powerful resources for understanding the target species. Genomes of domestic species have been used as a reference for unannotated genomes of wildlife (Hohenlohe et al. 2021), and reproductive techniques once applied to domestic species have been utilized in wildlife (Comizzoli and Wildt 2017). While it is important to understand that each species is ecologically, physiologically and behaviourally unique, domestic species can provide important information about evolutionarily similar species. For example, domestic ferrets have been used to advance the reproductive capabilities of both European mink (Mustela lutreola) and black-footed ferrets (Amstislavsky et al. 2008). The domestic dog has been used as a reference genome for multiple canid species, including the highly inbred Channel Island Fox (Urocyon littoralis; Robinson et al. 2016).

Advanced genomic and reproductive sciences have enhanced reintroductions, translocations and genetic rescue

Small populations that have become inbred due to matings between relatives are at risk of inbreeding depression, which results from the expression of deleterious alleles that can accumulate over time simply by chance (genetic load; for an overview see: van Oosterhout 2020). Animals with inbreeding depression show reduced fitness that manifests as reduced survivorship or fecundity (Hedrick and Fredrickson 2010). For example, inbred Scandinavian wolves bred less frequently and produced less offspring resulting in a population that declined over time (Åkesson et al. 2016). Two strategies are often suggested to reduce the impact of inbreeding depression in natural populations: purging and genetic rescue (Hedrick and Garcia-Dorado 2016; Bell et al. 2019, see also glossary). At least, in theory, maintaining a population at a small size should contribute to removing deleterious variation through purging, thus reducing the amount of genetic load and inbreeding depression. However, simulations have shown that methods aimed at enhancing purging by intentional inbreeding should not be generally advised in conservation programmes because this implies important reductions in effective population size leading to severe inbreeding depression in the short term (Caballero et al. 2017). Inbreeding is alleviated by mating of individuals in the inbred population with other individuals characterised by alleles not found in that population. The resulting offspring of that mating will be likely more fit than their parents and then survive longer or have more offspring. The population recovers and grows as a result of the addition of genetically unique individuals, defined as genetic rescue (Ralls et al. 2020 for a detailed overview). Genetic rescue has been observed to occur naturally when immigrants from a distant population integrate into an inbred one (reviewed in Frankham 2015). Genetic rescue has also been used successfully as a management tool for inbred populations, using translocated individuals e.g. in adders (Vipera berus, Madsen et al. 1999), Florida Panther (Puma concolor coryi, Johnson et al. 2010) or greater prairie chicken (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus, Westemeier et al. 1998), or translocations or interpopulation crosses in rare plant species (e.g. Pinus torrevana, Hamilton et al. 2017; Rutidosis leptorrhnynchoides, Pickup and Young 2008; Ranunculus reptans, Willi et al. 2007). In arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus, Hasselgren et al. 2021) and Isle Royale wolves (Canis lupus, Robinson et al. 2019) inbreeding could also be reduced through genetic rescue, although this effect was only significant in the first generation. The goal for conservation practitioners and wildlife managers is to determine (i) which individuals can provide genetic rescue, (ii) and where a source of those individuals can be found.

Determining which individuals to use for genetic rescue

If translocated or reintroduced individuals are too genetically similar to the target population in need of genetic rescue, then inbreeding will not be alleviated and an increase in fitness will not be observed. On the other hand, if translocated individuals are too genetically dissimilar from the target population, then outbreeding depression can occur. Outbreeding depression reduces fitness in the next generation as a result of mismatches in genetic compatibility between two individuals and/or the introduction of maladapted genes (Flanagan et al. 2018). Recent advances in genomics allow conservation practitioners to better understand if candidate individuals for translocation are a good fit for genetic rescue. First, a genomic screening is suggested in which genetic diversity, inbreeding and harmful mutations are assessed for both the population in need of genetic rescue as well as potential donor individuals (see also Fig. 3). Ideally, these donor individuals come from different source populations as this greatly enhances the genetic diversity that can be used for rescue. As this approach could increase the genetic load in the target population, some authors suggested to source individuals from partially-inbred populations (Robinson et al. 2018, 2019; Kyriazis et al. 2021). However, Ralls et al. (2020) recently highlight the limitations of these studies and argue to use source populations with high genetic diversity. In any case, intensive monitoring and rigorous evaluations will be needed to develop best practices for implementing genetic rescue measures (see Robinson et al. 2021b).

Determining the source of individuals to use for genetic rescue

The selection of suitable source populations is key for any reintroduction program (Houde et al. 2015). For this purpose, genomic data can provide very valuable and previously inaccessible insights into the evolutionary and demographic history of target and source populations (Hohenlohe et al. 2021). Relocation programs, while aiming at increasing genetic diversity, should also consider source populations from environments as similar as possible to the population to be augmented (e.g. Hedrick and Fredrickson 2010) to decrease the possibility of maladaptation/outbreeding depression. Such a situation arises when donor and recipient populations have developed different environmental adaptations and their offspring are less adapted to either habitat (Marshall and Spalton 2000). Identifying potential functional fitness-related variation enables direct assessments of candidate source population for preadaptation to the target environment, and for their potential for acclimation to the new environments through phenotypic plasticity (Cauwelier et al. 2018; Muchero et al. 2018). Despite the need to preserve adaptive variants and avoid the introduction of deleterious alleles in translocations (Kristensen et al. 2015), the general recommendation has been to prioritize overall genetic diversity and evolutionary potential more than specific variants or adaptations (Weeks et al. 2011; Kardos and Shafer 2018). Careful consideration of alternative source populations is thus required when planning translocation or reintroduction programs, so that closely related and ecologically similar populations are favoured and large populations with high genetic load are avoided when alternatives are available.

Genetic rescue has typically been conducted using live individuals that are translocated from either a wild or a captive population. Assisted reproduction technologies like artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization have been used in captive wildlife management for decades and have the possibility of being used for genetic rescue of wild populations (Comizzoli and Wildt 2017). In this case sperm, ova, or embryos from genetically valuable individuals would be used instead of live individuals to increase the genetic diversity of the recipient gene pool. Although technologically feasible, this technique has not been used for genetic rescue of in situ populations. Finally, instead of using germplasm, such as sperm or eggs, it has been proposed that non-reproductive somatic cells could be used to clone genetically valuable individuals that could then be used for genetic rescue. While this idea has been proposed earlier (Wisely et al. 2015), efforts have now led to successful protocols (Borges and Pereira 2019), which have only recently been used for genetic rescue in the Przewalski horse (Equus przewalskii; Hernandez 2020) and the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes; Imbler 2021). For potential ethical considerations of such approaches see Sandler et al. (2021).

A typical example of a ‘genetic rescue’ approach is the case of the California endemic Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana Parry). The species is one of the rarest pines in the world and of conservation concern with only two populations, occupying a mainland and an island (Hamilton et al. 2017). Based on a progeny trial for evaluation of phenotypic differences, the authors found genetic population-specific differences, with the island population having reduced genetic variability compared to the mainland population. The F1 hybrids (a cross between both populations) exhibited increased fitness (height and higher fecundity) compared to the parents. In this context, the authors suggest that intraspecific hybridization might help restore genetic variation capable of coping with environmental changes, thus preserving the evolutionary potential in rare species and realising the concept for ‘genetic rescue’.

Reintroduced populations are particularly susceptible to genetic erosion due to intense founder effects caused by usually a small number of released individuals, low survival and large variance in reproductive success during the establishment phase. As in the foundation of a captive population, the selection of animals for release should be focused on minimizing inbreeding and relatedness to allow optimal founder diversity and to avoid inbreeding accumulation in the first few generations. Any post-release genetic management will require accurate information on the survival and reproduction of the released individuals. Fortunately, this is greatly facilitated by the genetic profiling of scats, hair, moulted feathers, and other material obtained through non-invasive genetic sampling, suboptimal materials that allow, nevertheless, for the genotyping of an increasing number of genome-wide markers (von Thaden et al. 2020) and even the access to targeted (Perry et al. 2010) or whole genome sequences (Taylor et al. 2020). Intensive monitoring of reintroduced populations would then allow for an individual-based genetic management of subsequent releases during the establishment phase by selecting individuals that are minimally related to the current population.

The global Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) population in 2002 was less than 100 individuals distributed in two isolated remnant populations in Southern Spain. Whole-genome sequences revealed the Iberian lynx as one of the species with the lowest species- and genome-wide genetic diversity (Abascal et al. 2016), resulting from long-term small population sizes and recent bottlenecks. Historical and ancient genetic data suggested that currently observed genetic differentiation between the two remnant populations was driven by genetic drift and isolation, hence validating their admixture and the management of the species as a single management unit (Casas-Marce et al. 2013, 2017). The holistic conservation program included the establishment of an ex situ population and an intensive in situ program, which eventually incorporated translocations and an ambitious reintroduction program. Molecular marker data became an integral part of the management of the ex situ population since its conception, by contributing an empirical founder kinship matrix and by allowing the comparison of the genetic compositions of wild and captive populations and the monitoring of genetic diversity and inbreeding through time (Kleinman-Ruiz et al. 2019). Genetic management has been based on the principle of minimizing average kinship, so the priority for reproduction, pairings and releases are determined annually from the marker-assisted kinship matrix. Ongoing genome wide studies seek to identify potentially deleterious mutations relevant for inbreeding depression, as well as particular genetic variants associated with specific traits, information that could eventually be implemented in the management of the species. Once one of the most endangered felids in the world, the recent 2019 census yielded > 800 wild individuals living in the two remnants and six reintroduction areas, illustrating a very successful species recovery assisted by the application of genomic information and molecular tools.

How can genomic information help?

For the target population, it is important to know which specific mutations are causing the reduction in fitness when exposed in a homozygous state (i.e. which mutations contribute to the genetic load). Then the potential donor animals are genetically screened for the five important genomic measures as indicated in Box B “Genomic tools’ (see also Fitzpatrick and Funk 2019; Fitzpatrick et al. 2020). These genomic measures can be used to accurately estimate distinct genetic areas and assess inbreeding in populations, they have been used to design breeding schemes to select against deleterious alleles or to increase heterozygosity, and they have the potential to increase the long-term survival of breeds and wild populations in view of climate change (for an overview see Kristensen et al. 2015). For evaluating overall adaptive potential whole genome, or at least genome-wide screenings, may remain the preferred option (Flanagan et al. 2018; Bourgeois and Warren 2021).

Genomic analyses of source populations could also allow the identification of genetic variation underlying (or simply linked to) traits that increase fitness in particular environments. Although there are a few examples of successful identification of the genetic basis of particular traits in natural populations (e.g. Anderson et al. 2009; Fulgione et al. 2016; Benazzo et al. 2017; Christmas et al. 2019), this remains a challenging task, despite the increasing availability of annotated reference genomes (Kardos et al. 2016). Such a problem is particularly daring for endangered species, as they present severe limitations in sample sizes, phenotypic data, and experimental approaches. Here ex situ populations can be of help, as they offer ample opportunities for combining e.g. behavioural and demographic data with genomic profiles, and access to samples either directly from zoos, aquariums and botanic gardens or from large collections in biobanks (such as the EAZA Biobank or the Millenium Seed Bank). Finally, transcriptomic analyses can inform on the ability of particular individuals, or populations, to change expression levels in response to environmental stressors anticipated at the reintroduction area, either at candidate response genes when these have been previously identified, or globally when these remain unknown (He et al. 2016).

A similar challenge to variants under positive selection due to local adaptation exists for the detection of variants that have detrimental effects. Recent genomics methodologies have been developed to assess the potential impact of mutations that are present in genomes, without the need of phenotypes to test their harmful nature. Such bioinformatic identification of deleterious alleles rely on evolutionary conservation (Cooper et al. 2005; Pollard et al. 2010), physicochemical properties and their putative effect on the functionality of genes (Ng and Henikoff 2003) or combined approaches (Kircher et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2010). Although the deleteriousness of single variants remains notoriously difficult to predict from sequence data alone, when combined they can provide a reliable estimate of genetic load in a comparative framework (van der Valk et al. 2019; von Seth et al. 2021).

Questions to consider prior to management action

Prior to initiating a genetic rescue program, conservation practitioners should consider several questions. As with any conservation action, defining the problem that needs to be solved is paramount. Thus for genetic rescue, a first question to consider is:

-

Does the population decline have a genetic cause, i.e. is there reduced fitness in the population?

Previous studies have conducted time series analysis of population size and inbreeding (Åkesson et al. 2016), or assessed correlations of fitness and levels of inbreeding (Santymire et al. 2019). Genomic methods increasingly provide a robust method for identifying maladaptations or recessive alleles.

-

Have genomes been sequenced for the target species so that different populations can be analysed and potential maladaptations be assessed?

Historically, living individuals or seeds from different populations have been the source of genomes for genetic rescue. If genomes of living individuals are available we can use bioinformatic tools to pinpoint potential deleterious mutations within the genome and choose individuals with the lowest load. As an alternative to such wild or domestic individuals, advanced reproductive science makes it possible to use cryopreserved semen or embryos (Comizzoli and Wildt 2017) or even cryopreserved fibroblasts (Wisely et al. 2015). Ultimately, source material may come in the form of living organisms or biobank samples from ex situ or in situ populations.

-

Are the source genomes compatible with the gene pool of the recipient population and do they have the potential to increase fitness?

Advances in genomic analyses will allow for better matching between source and recipient gene pools so that inbreeding depression is alleviated yet outbreeding depression or other genomic pitfalls are avoided. In addition, individuals with high genetic load could be identified as unsuitable as a source for translocation (Kyriazis et al. 2021). Therefore screening genomic samples not only from the recipient population, but also the source population is desirable.

-

What technical expertise is required to integrate source and recipient gene pools?

It is important to understand the technical feasibility of a genetic rescue operation. Wild animal or plant translocations have requirements that would be different from using animals or plants from captive breeding facilities or botanical gardens. Genetic rescue from cryopreserved samples is technologically complicated and requires feasibility tests on different levels (from fertilization of a single individual to implementing such information in a wild population). For example, advanced reproductive science techniques such as cryopreservation, artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization and cloning would need to be optimised for each species for which the specific technology is being considered.

-

How will success be measured?

Genetic rescue implies that success is not solely an increase in population size, but also increased reproduction, survival, and adaptation potential in the target population. Therefore monitoring of recipient populations for population vital rates is key. However, genomic and biotechnological tools are only a small part of the overall toolbox.

Facilitating adaptation to changing environments through biotechnological applications

Genetic diversity is the underlying prerequisite for all species to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Ecosystem resilience thus highly depends on genetic variation (see Hoban et al. 2021; Stange et al. 2021). Genomic tools now enable us to assess the adaptive potential of species and identify particular loci underlying adaptation. Such genomic information is adopted in commercial animal and plant breeding to predict the phenotype of individuals and identify potential shifts in phenotypes (Meuwissen et al. 2001; Georges et al. 2019). Only recently has it been applied in wild populations, e.g. to identify the basis of the shift in egg laying date in great tits (Parus major) (Gienapp et al. 2019) or multiple morphological traits such as weight, horn length or coat color in soay sheep (Ovis aries) (Ashraf et al. 2020) or drought, freezing tolerance, warmer temperatures or salt stress in plants and trees (Exposito-Alonso et al. 2018; Browne et al. 2019). Genomic knowledge of specific genes can not only be used to identify specific variants of interest (e.g. Shryock et al. 2021) but the genetic code can also be altered by targeted changes of an organism's genome, also known as genome editing (see glossary). This approach encompasses a wide variety of tools using site-specific enzymes. Currently, the CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease system (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated protein) is commonly used in many research fields (such as agriculture and medicine) and the attempts to alter or introduce genes with the goal of enhancing species survival against specific threats, such as disease or climate change are discussed widely (for an overview see Piaggio et al. 2017; Redford et al. 2019). The versatility, simplicity, and efficacy of the CRISPR technology offer the researchers previously unattainable levels of precision and control over genomic modifications, making it the most widely used among the genome editing tools (Bewg et al. 2018). While the application of genome editing tools in many wild animal species is still in its infancy, it has already been demonstrated in forest trees such as poplars (Populus) (Elorriaga et al. 2018) and woody perennials (Tsai and Xue 2015) and we can expect an increasing genomic knowledge to develop strategies for disease resistance (Naidoo et al. 2019; Dort et al. 2020).

Changing environmental conditions such as increasing sea temperatures are threatening marine ecosystems and especially corals that suffer from mass bleaching. Thus, thermal adaptation is crucial for their persistence. Heat tolerance can be inherited and natural variation in temperature tolerance may thus facilitate adaptation (Dixon et al. 2015). Specific genes which are responsible for heat tolerance have already been identified through gene editing techniques (Cleves et al. 2020). This knowledge helps to understand which genetic traits are controlling heat tolerance of corals and might thus be useful targets for future genetic engineering and enhancing thermal tolerance (van Oppen et al. 2017).

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a fast-growing and long-lived keystone tree species in the eastern United States and Canada (Powell et al. 2019). An invasive fungal pathogen Chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) has been introduced from Asia into the United States in the late 1800s. Since then it has been spreading throughout the species range killing around 90% of the population (Merkle et al. 2007; Powell et al. 2019). The American Chestnut Foundation (https://www.acf.org) has implemented a breeding program that tries to incorporate the blight resistance of Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) into the American chestnut trees by backcross breeding. While this has been partly promising, inheritance by future generations is inconsistent and will likely require many generations of breeding (Steiner et al. 2017). Thus genetically engineered blight-tolerant American chestnut trees have been developed and those first transgenic American chestnut trees were planted in field trials in 2006 (Steiner et al. 2017). While transgenic trees are mostly developed for economic purposes, the chestnut trees represent the first example of genome editing as part of a restoration strategy for conservation purposes (Merkle et al. 2007). The US Department of Agriculture has started a regulatory review of the proposed transgenic American chestnut in August 2020, including a period of public comment.

Questions to consider prior to further integration of genome editing for management

Genome editing and the introduction of additional variation into the genome of wild organisms are based on the genomic information available in different populations of the target species. In case a genome editing approach might be considered several key questions need to be answered ahead:

-

Is full genome/transcriptome information for the target species available?

-

Is that information available across different populations or subspecies?

-

Is the target species related to a model species?

If genome information is accessible then we need to identify if and how this information relates to specific phenotypes.

-

Can target genes potentially be identified?

-

Are the traits which should be altered controlled by a single gene or multiple genes?

By identifying the underlying genomic basis for specific traits we can start experiments. For this, we need to have additional information.

-

What is the breeding system of the organism?

-

Can these organisms be kept in an experimental setting under different environments?

Managing/eradication of invasive species

Invasive species are within the five key drivers of biodiversity loss and extinction with 20% of extinctions being attributed to invasive alien species and 54% partially caused by them (Clavero and García-Berthou 2005). However, the management and eradication of invasive alien species is challenging and needs case by base evaluations due to different ways of spreading, life cycles and reproduction strategies. Currently managing invasives is mostly done through mechanical, chemical and biological controls, bio pesticides or the mass release of sterile individuals (Wittenberg and Cock 2001; Teem et al. 2020). While those tools have shown to be partly successful, they are labour and cost-intensive and, therefore, difficult to scale up to larger areas (Glen et al. 2013). There can also be negative side effects on non-target species that can result as bycatch products, or when using chemicals and introducing allochthonous natural predators (Messing and Wright 2006; Glen et al. 2007). Genetic information can complement the existing integrated invasive alien species management programmes by providing relevant information on, e.g. hybridisation mechanisms (van de Crommenacker et al. 2015) and physiological adaptation to different conditions (i.e. transcriptomic studies) (Luo et al. 2020; Clark et al. 2021). Increasing numbers of genomes are currently being sequenced or already available for many invasive species, providing key information on their biology, evolution and invasive spread (Prentis et al. 2008; North et al. 2021).

The processes during an invasion can be tracked through molecular data and understanding the history of invasions can inform management of current and future introductions (Hamelin and Roe 2020). Information on the temporal and spatial dynamics of an invasion also helps to develop a biosurveillance system (Westfall et al. 2020), where pests and pathogens could be identified and pathways of spread assessed (Hamelin and Roe 2020).

Genomic information can give valuable insight whether genetic variability in native species can be linked to invasiveness. The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is a phloem-feeding beetle that is native to Asia but invasive in North America where it has been identified to be an extremely destructive pest for ash trees (Fraxinus spp.) (Global Invasive Species Database 2020). Studies comparing the genomes of the most susceptible North American ashes (F. americana, F. pennsylvanica, F. nigra) with the resistant species F. mandshurica in Asia mapped defence related genes and identified candidate genes linked to resistance (Lane et al. 2016; Kelly et al. 2019). This ultimately can lead to improved future ash breeding programmes (Bai et al. 2011).

A different approach is used when the genomic composition of the invasive species itself is analysed by identifying the genes and causative mutations that play an important role in the evolution of invasiveness. Studying the actual function of such genes can be combined with phenotypic traits of interest (Prentis and Pavasovic 2013). Identified resistance genes could then be monitored and potentially increased for sexually reproductive species. The introduction or modification of a genetic trait that would negatively affect the reproductive ability of the invasive alien species could be achieved by a so-called gene drive (see Box A; Alphey et al. 2020). This mechanism can be observed in nature in fungi, yeast and other organisms, and allows a gene to be passed to the progeny through sexual reproduction at a higher inheritance rate, even if it does not confer a competitive advantage (Burt and Trivers 2006). Possibilities to apply gene drive for invasive species eradication management plans involve targeting specific genes involved in main physiological functions or reproduction (i.e., for arthropods). Recently, the potential use of gene drives for the management of populations has been discussed and described in detail in Rode et al. (2019). However, the development of gene drives for conservation applications is still at a very early stage, and further investigations are required to evaluate their feasibility as well as potential impacts both positive and negative (for a recent review see Price et al. 2020).

Case studies of biotechnology in wild organisms

Avian malaria

Similar to efforts taking place to tackle human malaria using gene drive approaches (Burt et al. 2018), researchers are investigating potential new tools to eliminate avian malaria threatening Hawaiian birds. Avian malaria is the driver for the native bird population extinction and decline (Atkinson and Lapointe 2009). The avian malaria vector mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus) is an alien invasive species in Hawaii (Kenis et al. 2009). Different interventions involving genetic approaches are being considered. For instance, using a gene drive approach to make the invasive mosquitoes refractory to avian malaria (gene drive population alteration approach) or reducing the population of invasive mosquitoes by driving infertility traits or biasing the sex ratio (gene drive population suppression approach) (National Academies Science, Engineering, Medicine 2016). The US Fish and Wildlife Service, Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources, and the American Bird Conservancy are also looking at the potential use of Wolbachia, a naturally-occurring bacteria that can lead to the absence of viable progeny (Redford et al. 2019). This approach has been used to control another invasive mosquito species Aedes aegypti, which is one of the key vectors for dengue and Zika viruses (Hoffmann et al. 2011). This research on new approaches to tackle avian malaria is still at an early stage and is expected to benefit from some of the discoveries made in human malaria research, where the research is more advanced, partly because of higher attention from researchers, funders and the public.

Potential of suppression of invasive social wasps

The invasive common wasp (Vespula vulgaris) originally native to Eurasia is listed among the 100 world worst invasive alien species (Lowe et al. 2000). In New Zealand the common wasp predates 0.8–4.8 million loads of prey/ha, exerting an annual cost of about NZ$133 million. Due to the high densities of wasp populations that cover over more than a million hectares of native forest, the environmental impact of using pesticides is prohibitive and risky for biodiversity. Modellers have demonstrated the potential of a CRISPR-based gene drive mechanism that would target spermatogenesis genes with likely male-specific expression to obtain modified-queens (Lester et al. 2020). When a modified-queen mates with wild-type males it will produce fertile workers carrying modified genes and thus propagate it to the next generation, but if it mates with a genetically modified male, fertilization will fail and all offspring will be male. This nest will fail and die in spring or early summer as males do not forage or aid in nest maintenance. A spermatogenesis gene drive could thus potentially reduce the wasp population and depending on population dynamics, locally eradicate those invasive wasps (Rode et al. 2019).

Invasive rodent eradication on islands

Since the 1960s, conservation efforts have focused on restoring the islands' biodiversity by eradicating invasive rodents (particularly because they are destroying native fauna and flora). The use of gene drive to eradicate rodents requires special knowledge and precautions to ensure that the intervention remains on the target populations and does not affect populations of rodents where they are native species. The proposed approaches (Lindholm et al. 2016; Harvey-Samuel et al. 2017; Piaggo et al. 2017; Campbell et al. 2019) are to bias sex ratio of the invasive rodents’ offspring, and to get this modification inherited at a high ratio, which would reduce or completely suppress the population due to lack of reproduction and natural attrition. This is still under development in the laboratories and the release of modified mice into the wild is likely to be in the distant future. This gene drive approach offers a potentially attractive alternative to the use of toxicants for eradication and can serve as an important tool to reduce invasive rodent pests, island predators, or zoonotic disease hosts (e.g. house mice, Mus musculus, and three rat species; Rattus norvegicus, R. rattus and R. exulans).

Questions to consider prior to further integration of gene drives for targeting invasive species

While some conservationists already discuss the use of gene drives for conservation management the technologies are still in development and will not be readily applicable in the near future. For practitioners and managers that means that gene drives will need further rigorous research—both in containment and potentially with small-scale field evaluations—before they can be applied to address specific challenges. Several key questions have to be asked for potential projects:

-

What is the success rate of previous control attempts?

-

Is there any genomic information available for the target species and the target genes?

-

What are the benefits of using a potential gene drive approach?

-

What is the timeframe and scale on implementing invasive disease control?

-

Is there a risk of the gene drive technology spreading to a non-target population (either in a location where the species is not invasive, or to a non-invasive related species through hybridisation).

-

Would gene drive technology obtain social, ethical, and regulatory acceptability? And what are stakeholder perceptions/views for acceptance and engagement in genetic biocontrol?

In cases where gene drives could be established in model organisms successfully some additional points have to be asked.

-

Is the generation length short enough for a gene drive approach to have an effect in a relevant timescale for humans and nature?

-

Does the target organism reproduce sexually?

Currently it is very clear that gene drives cannot be uniformly applied to all organisms. Short generation times and high offspring rates such as in mosquitoes can make the intervention relevant. Before planning field trials one has to consider:

-

Are there co-occurring native species at the target site which might be affected through hybridisation?

-

Can the risk assessment of field trials be done on the basis of a deployment hypothesis?

-

What are the potential risks for the accidental or deliberate release of genetically modified organisms into non-target populations?

Conclusion

The crux of almost all management actions is to obtain comprehensive knowledge of the target species to inform decision making, including data on population size and habitat use, behavioural data like colonisation ability, generation time, and reproductive mode. Many of these questions can be confidently addressed using microsatellites or a few hundred SNPs. However, with genomic information being increasingly available for many species (Hohenlohe et al. 2021), we gain additional insight, as on the demographic history or introgression patterns, thus providing relevant information for species management. Genomic technologies are increasingly being applied in ex situ and in situ management and genomic screenings are necessary to identify the most suitable individuals for breeding programs, translocations and genetic rescue in terms of genetic relatedness and to avoid increasing genetic load in the target population. Genomic variation also helps to more efficiently fight potential diseases and combat climate change by identifying genetic variation of specific traits that increase fitness in particular environments. In addition, knowledge from genomes helps us to compare contemporary populations as well as allowing temporal comparisons in more detail and thus enables us to estimate the magnitude of change across populations and time. Genomic information is equally important for cloning representatives of highly endangered or even extinct species, where the first achievements have been made. In this context, a state-of-the-art collection and storage of seeds, tissues, and cells in biobanks are invaluable. Comprehensive genomic knowledge is also essential for gene editing of organisms in support of their adaptation to environmental changes or for combating pathogens. This practice of genome modification has already been applied in plant taxa, model species, and even in humans, and holds great potential for conservation applications at the individual level. On the population level gene drives are currently developed to be applied on pest species, for which other eradication interventions have not succeeded. The broad range of biotechnological and genomic tools can help conservation practitioners and managers to resolve some of the most pressing conservation challenges, whilst at the same time actions should be made to secure habitat and provide species protection. However, a careful case-by-case risk assessment for potential applications is required, and ethical and political aspects need to be considered (Breed et al. 2019; Redford et al. 2019). While some tools are already well established, others still need to be tested and will only be applicable in the future (Fig. 2).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Abascal F, Corvelo A, Cruz F, Villanueva-Cañas JL, Vlasova A, Marcet-Houben M, Martínez-Cruz B, Cheng JY, Prieto P, Quesada V, Quilez J, Li G, García F, Rubio-Camarillo M, Frias L, Ribeca P, Capella-Gutiérrez S, Rodríguez JM, Câmara F, Lowy E, Cozzuto L, Erb I, Tress ML, Rodriguez-Ales JL, Ruiz-Orera J, Reverter F, Casas-Marce M, Soriano L, Arango JR, Derdak S, Galán B, Blanc J, Gut M, Lorente-Galdos B, Andrés-Nieto M, López-Otín C, Valencia A, Gut I, García JL, Guigó R, Murphy WJ, Ruiz-Herrera A, Marques-Bonet T, Roma G, Notredame C, Mailund T, Albà MM, Gabaldón T, Alioto T, Godoy JA (2016) Extreme genomic erosion after recurrent demographic bottlenecks in the highly endangered Iberian lynx. Genome Biol 17:251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1090-1

Åkesson M, Liberg O, Sand H, Wabakken P, Bensch S, Flagstad Ø (2016) Genetic rescue in a severely inbred wolf population. Mol Ecol 25(19):4745–4756. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13797

Alphey LS, Crisanti A, Randazzo FF, Akbari OS (2020) Opinion: standardizing the definition of gene drive. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(49):30864–30867. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020417117

Amador C, Hayes BJ, Daetwyler HD (2014) Genomic selection for recovery of original genetic background from hybrids of endangered and common breeds. Evol Appl 7:227–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12113

Amstislavsky S, Lindeberg H, Alto JA, Kennedy MW (2008) Conservation of the European mink (Mustela lutreola): Focus on reproduction and reproductive technologies. Reprod Domest Anim 43:502–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00950.x

Anderson TM, von Holdt BM, Candille SI, Musiani M, Greco C, Stahler DR, Smith DW, Padhukasahasram B, Randi E, Leonard JA, Bustamante CD, Ostrander EA, Tang H, Wayne RK, Barsh GS (2009) Molecular and evolutionary history of melanism in North American gray wolves. Science 323(5919):1339–1343. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165448

Ashraf B, Hunter DC, Bérénos C, Ellis PA, Johnston SE, Pilkington JG, Pemberton JM, Slate J (2020) Genomic prediction in the wild: a case study in Soay sheep. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.205385

Atkinson CT, LaPointe DA (2009) Introduced avian diseases, climate change, and the future of Hawaiian honeycreepers. J Avian Med Surg 23(1):53–63. https://doi.org/10.1647/2008-059.1

Bai X, Rivera-Vega L, Mamidala P, Bonello P, Herms DA (2011) Transcriptomic signatures of Ash (Fraxinus spp.) phloem. PLoS ONE 6(1):e16368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016368

Barbosa S, Mestre F, White T, Paupério J, Alves P, Searle J (2018) Integrative approaches to guide conservation decisions: using genomics to define conservation units and functional corridors. Mol Ecol 27:3452–3465. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14806

Bard NW, Miller CS, Bruederle LP (2021) High genomic diversity maintained by populations of Carex scirpoidea subsp. convoluta, a paraphyletic Great Lakes ecotype. Conserv Genet 22:169–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-020-01326-x

Baveja P, Garg KM, Chattopadhyay B, Sadanandan KR, Prawiradilaga DM, Yuda P, Lee JGH, Rheindt FE (2020) Using historical genome-wide DNA to unravel the confused taxonomy in a songbird lineage that is extinct in the wild. Evol Appl 14(3):698–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13149

Bell D, Robinson Z, Funk C, Fitzpatrick S, Allendorf F, Tallmon D, Whiteley A (2019) The exciting potential and remaining uncertainties of genetic rescue. Trends Ecol Evol 34(12):1070–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.06.006

Benazzo A, Trucchi E, Cahill JA, Maisano Delser P, Mona S, Fumagalli M, Bunnefeld L, Cornetti L, Ghirotto S, Girardi M, Ometto L, Panziera A, Rota-Stabelli O, Zanetti E, Karamanlidis A, Groff C, Paule L, Gentile L, Vilà C, Vicario S, Boitani L, Orlando L, Fuselli S, Vernesi C, Shapiro B, Ciucci P, Bertorelle G (2017) Survival and divergence in a small group: the extraordinary genomic history of the endangered Apennine brown bear stragglers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:E9589–E9597. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707279114

Bewg WP, Ci D, Tsai C-J (2018) Genome editing in trees: from multiple repair pathways to long-term stability. Front Plant Sci 9:1732. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01732

Borges AA, Pereira AF (2019) Potential role of intraspecific and interspecific cloning in the conservation of wild mammals. Zygote 27:111–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0967199419000170

Boscari E, Marino IAM, Caruso C, Gessner J, Lari M, Mugue N, Barmintseva A, Suciu R, Onara D, Zane L, Congiu L (2021) Defining criteria for the reintroduction of locally extinct populations based on contemporary and ancient genetic diversity: the case of the Adriatic Beluga sturgeon (Huso huso). Divers Distrib 27:816–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13230

Bourgeois YX, Warren BH (2021) An overview of current population genomics methods for the analysis of whole-genome resequencing data in eukaryotes. Mol Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15989

Bragg JG, Cuneo P, Sherieff A, Rossetto M (2020) Optimizing the genetic composition of a translocation population: Incorporating constraints and conflicting objectives. Mol Ecol Resour 20:54–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13074

Breed MF, Harrison PA, Blyth C, Byrne M, Gaget V, Gellie NJC, Groom SVC, Hodgson R, Mills JG, Prowse TAA, Steane DA, Mohr JJ (2019) The potential of genomics for restoring ecosystems and biodiversity. Nat Rev Genet 20(10):615–628. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0152-0

Brown AHD, Marshall DR (1995) A basic sampling strategy: theory and practice. Collecting plant genetic diversity: technical guidelines, vol 75. CAB International, Wallingford, p 91

Browne L, Wright JW, Fitz-Gibbon S, Gugger PF, Sork VL (2019) Adaptational lag to temperature in valley oak (Quercus lobata) can be mitigated by genome-informed assisted gene flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116:25179–25185. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908771116

Burt A, Trivers R (2006) Genes in conflict—the biology of selfish genetic elements. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674029118

Burt A, Coulibaly M, Crisanti A, Diabate A, Kayondo JK (2018) Gene drive to reduce malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. J Responsib Innov 5:66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1419410

Byers O, Lees C, Wilcken J, Schwitzer C (2013) The one plan approach: the philosophy and implementation of CBSG’s approach to integrated species conservation planning. WAZA Magazine 14:2–5

Caballero A, Bravo I, Wang J (2017) Inbreeding load and purging: implications for the short-term survival and the conservation management of small populations. Heredity 118:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.80

Campbell KJ, Saah JR, Brown PR, Godwin J, Gould F, Howald GR, Piaggio A, Thomas P, Tompkins DM, Threadgill D, Delborne J, Kanavy DM, Kuiken T, Packard H, Serr M, Shiels A (2019) A potential new tool for the toolbox: assessing gene drives for eradicating invasive rodent populations. In: Veitch CR, Clout MN, Martin AR, Russell JC, West CJ (eds) Island invasives: scaling up to meet the challenge. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Gland, pp 6–14

Caplancq T, Fitzpatrick MC, Bay RA, Exposito-Alonso M, Keller SR (2020) Genomic prediction of (Mal) adaptation across current and future climatic landscapes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 51:245–269. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-020720-042553

Carvalho CS, Forester BR, Mitre SK, Alves R, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Ramos SJ, Resende-Mpreira LC, Siqueira JO, Trevelin LC, Caldeira CF, Gastauer M, Jaffé R (2021) Combining genotype, phenotype, and environmental data to delineate site-adjusted provenance strategies for ecological restoration. Mol Ecol Resour 21:44–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13191

Casas-Marce M, Soriano L, López-Bao JV, Godoy JA (2013) Genetics at the verge of extinction: insights from the Iberian lynx. Mol Ecol 22:5503–5515. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12498

Casas-Marce M, Marmesat E, Soriano L, Martínez-Cruz B, Lucena-Perez M, Nocete F, Rodríguez-Hidalgo A, Canals A, Nadal J, Detry C, Bernáldez-Sánchez E, Fernández-Rodríguez C, Pérez-Ripoll M, Stiller M, Hofreiter M, Rodríguez A, Revilla E, Delibes M, Godoy JA (2017) Spatiotemporal dynamics of genetic variation in the Iberian lynx along its path to extinction reconstructed with ancient DNA. Mol Biol Evol 34(11):2893–2907. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx222

Cauwelier E, Gilbey J, Sampayo J, Stradmeyer L, Sj M (2018) Identification of a single genomic region associated with seasonal river return timing in adult Scottish Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), using a genome-wide association study. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 75:1427–1435. https://doi.org/10.1139/CJFAS-2017-0293

CBD (2020) Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Global biodiversity outlook 5 – Summary for policy makers

Ceccarelli V, Fremout T, Zavaleta D, Lastra S, Correa SI, Arévalo-Gardini E, Rodriguez CA, Cruz Hilacondo W, Thomas E (2021) Climate change impact on cultivated and wild cacao in Peru and the search of climate change-tolerant genotypes. Divers Distrib 2021(00):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13294

Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B (1999) The genetic basis of inbreeding depression. Genet Res 74:329–340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672399004152

Che-Castaldo J, Gray SM, Rodriguez-Clark KM, Schad Eebes K, Faust LJ (2021) Expected demographic and genetic declines not found in most zoo and aquarium populations. Front Ecol Environ 2021:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2362

Christmas MJ, Wallberg A, Bunikis I, Olsson A, Wallerman O, Webster MT (2019) Chromosomal inversions associated with environmental adaptation in honeybees. Mol Ecol 28:1358–1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14944

Clark MS, Peck LS, Thyrring J (2021) Resilience in greenland intertidal mytilus: the hidden stress defense. Sci Total Environ 767(9):144366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144366

Clavero M, García-Berthou E (2005) Invasive species are a leading cause of animal extinctions. Trends Ecol Evol 20(3):110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.003

Cleves AP, Tinoco AI, Bradford J, Perrin D, Bay LK, Pringle JR (2020) Reduced thermal tolerance in a coral carrying CRISPR-induced mutations in the gene for a heat-shock transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(46):28899–28905. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920779117

Colicchio JM, Herman J (2020) Empirical patterns of environmental variation favor adaptive transgenerational plasticity. Ecol Evol 10:1648–1665

Comizzoli P, Wildt DE (2017) Cryobanking biomaterials from wild animal species to conserve genes and biodiversity: relevance to human biobanking and biomedical research. In: Hainaut P, Vaught J, Zatloukal K, Pasterk M (eds) Biobanking of human biospecimens. Springer, Cham, pp 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55120-3_13

Cooper GM, Stone EA, Asimenos G, Green ED, Batzoglou S, Sidow A (2005) Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence. Genome Res 15:901–913. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.3577405

De Villemereuli P, Rutschmann A, Lee KD, Ewen JG, Brekke P, Santure AW (2019) Little adaptive potential in a threatened passerine bird. Curr Biol 29:889–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.072

Díez-Del-Molino D, von Seth J, Gyllenstrand N, Widemo F, Liljebäck N, Svensson M, Sjögren-Gulve P, Dalén L (2020) Population genomics reveals lack of greater white-fronted introgression into the Swedish lesser white-fronted goose. Sci Rep 10:18347. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75315-y

DiFazio SP, Leonardi S, Slavov GT, Garman SL, Adams WT, Strauss SH (2012) Gene flow and simulation of transgene dispersal from hybrid poplar plantations. New Phytol 193:903–915

Dixon G, Davies SW, Aglyamova G, Meyer E, Bay LK, Matz M (2015) Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science 348:1460–1462

Dort EN, Tanguay Ph, Hamelin RC (2020) CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing: an unexplored frontier for forest pathology. Front Plant Sci 11:1126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01126

Dussex N, von Seth J, Robertson BC, Dalén L (2018) Full mitogenomes in the critically endangered Kākāpō reveal major post-glacial and anthropogenic effects on neutral genetic diversity. Genes (basel) 9(4):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9040220

Ekblom R, Galindo J (2011) Applications of next generation sequencing in molecular ecology of nonmodel organisms. Heredity 107:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2010.152

Elorriaga E, Klocko AL, Ma C, Strauss SH (2018) Variation in mutation spectra among CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenized poplars. Front Plant Sci 9:594. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00594

Exposito-Alonso M, Vasseur F, Ding W, Wang G, Burbano HA, Weigel D (2018) Genomic basis and evolutionary potential for extreme drought adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Ecol Evol 2:352–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0423-0

Fant JB, Havens K, Kramer AT, Walsh SK, Calicrate T, Lacy RC, Maunder M, Meyer AH, Smith PP (2016) What to do when we can’t bank on seeds: what botanic gardens can learn from the zoo community about conserving plants in living collections. Am J Bot 103(9):1541–1543. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1600247

Fernández J, Toro MA, Gómez-Romano F, Villanueva B (2016) The use of genomic information can enhance the efficiency of conservation programs. Anim Front 6:59–64. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2016-0009

Fitzpatrick SW, Funk WC (2019) Genomics for genetic rescue. In: Rajora OP (ed) Population genomics. Springer, Cham, pp 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/13836_2019_64

Fitzpatrick SW, Bradburd GS, Kremer CT, Salerno PE, Angeloni LM, Funk WC (2020) Genomic and fitness consequences of genetic rescue in wild populations. Curr Biol 30(3):517–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.062

Flanagan SP, Forester BR, Latch EK, Aitken SN, Hoban S (2018) Guidelines for planning genomic assessment and monitoring of locally adaptive variation to inform species conservation. Evol Appl 11:1035–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12569

Frandsen P, Fontsere C, Nielsen SV, Hanghøj K, Castejon-Fernandez N, Lizano E, Hughes D, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Korneliussen TS, Carlsen F, Siegismund HR, Mailund T, Marques-Bonet T, Hvilsom C (2020) Targeted conservation genetics of the endangered chimpanzee. Heredity 125:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0313-0

Frankham R (2008) Genetic adaptation to captivity in species conservation programs. Mol Ecol 17(1):325–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03399.x

Frankham R (2015) Genetic rescue of small inbred populations: meta-analysis reveals large and consistent benefits of gene flow. Mol Ecol 24(11):2610–2618. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13139

Fulgione D, Rippa D, Buglione M et al (2016) Unexpected but welcome. artificially selected traits may increase fitness in wild boar. Evol Appl 9:769–776

Galla SJ, Moraga R, Brown L, Cleland S, Hoeppner MP, Maloney RF, Richardson A, Slater L, Santure AW, Steeves TE (2020) A comparison of pedigree, genetic and genomic estimates of relatedness for informing pairing decisions in two critically endangered birds: Implications for conservation breeding programmes worldwide. Evol Appl 2020(13):991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12916

Gallego-Bartolomé J (2020) DNA methylation in plants: mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. New Phytol 227:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16529

Gama MAM, Carolino I, Landi V, Delgado JV, Vicente AA et al (2013) Genetic structure, relationships and admixture with wild relatives in native pig breeds from Iberia and its islands. Genet Sel Evol 45:18

Gantz VM, Jasinskiene N, Tatarenkova O, Fazekas A, Macias VM, Bier E, James AA (2015) Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(49):E6736-6743. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521077112

Garrood WT, Kranjc N, Petri K, Kim DY, Guo JA, Hammond AM, Morianou I, Pattanayak V, Joung JK, Crisanti A, Simoni A (2021) Analysis of off-target effects in CRISPR-based gene drives in the human malaria mosquito. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(22):e2004838117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004838117