Abstract

Inspired by Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, many East Asian ethical leaders have aspired to emulate seemingly unattainable sages and buddhas throughout history. This aspiration challenges the common psychological view that significant gaps between role models and actual selves might hinder emulation motivation. It also differs from Western findings, which suggest that ethical leadership often emerges from emulating attainable exemplars like immediate supervisors or mentors. To decipher this intriguing emulation behavior in East Asia, this study employed a multiple-case approach involving 25 ethical leaders from Taiwan. Results indicate that these ethical leaders formulate three approaches to sustain emulation motivation for seemingly unattainable exemplars. First, they draw on East Asian philosophies to address demotivating factors such as ego threats and goal unattainability. Second, they embrace the cultural values of the Sinosphere, amplifying motivators like self-betterment, altruism, and life purpose. Lastly, they capitalize on the collective tendency of their culture to assimilate positive environmental influences, including societal norms and social support. These findings elucidate how and why many East Asian ethical leaders sustain buddha/sage emulation: The cultural resources of the Sinosphere nurture effective psychological strategies, underpinned by universal psychological mechanisms that suggest wider applicability across various societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“A good example is the best sermon.” This adage underscores the significance of ethical role modeling in fostering moral development across diverse cultural contexts. In the West, such perspective can be traced back to Aristotle (Osman, 2019). In the East, Confucius emphasized that virtuous figures have the power to influence others, as a gentle wind sways the grass (Analects 12:19). Their philosophical assertions have been scientifically validated by empirical research in moral education and management (e.g., Bandura & McDonald, 1963; Weaver et al., 2005). Although both the East and the West value ethical role modeling, their emulation approaches significantly differ.

West vs. East: Attainable vs. Unattainable Ethical Role Modeling

Empirical studies in the West have shown that ethical role modeling in the workplace is a side-by-side phenomenon (Weaver et al., 2005), with managers emulating their immediate superiors or mentors more likely to exhibit ethical leadership (Brown & Treviño, 2013). In contrast, those admiring higher-up executives often are not seen as ethical leaders. This finding is supported by social learning theory, which suggests effective learning is formed through observing and imitating those in the surroundings (Bandura, 1977, 1991), and ideal identity research, which indicates that large gaps between one's actual self and role models can deter emulation motivation (Oyserman & James, 2011). Hence, the Western literature suggests that ethical emulation requires attainable role models.

In contrast, East Asia sees a millennia-old tradition of modeling seemingly unattainable sages and buddhas. In Confucianism and Daoism, achieving Sagehood is considered exceptionally rare for the masses (Hung, 2016; Sellmann, 1987; Tan, 2021b), while Mahāyāna Buddhism, the region's main Buddhist tradition (Tu, 2015), asserts that attaining Buddhahood requires infinite time and immense efforts (Drewes, 2021; Powers, 2017). Yet, many East Asians have aspired to pursue Sagehood or Buddhahood. Historically, Mencius (the philosophical heir of Confucius) advocated for the pursuit of Sagehood (Mengzi 2B:2). Sima Qian of the Han dynasty (the father of Chinese historiography) deeply admired Confucius’ virtues. Neo-Confucians during the Song and Ming dynasties ardently explored how to become sages (Tu, 1980). Consequently, the merchant class of the Ming and Qing dynasties aspired to follow the Sagely Way (Yü, 2021), exemplifying Confucian ethical leadership through moral character and societal contributions (e.g., Liu, 2020; Yuan, 2013; Yuan et al., 2023).

This legacy persists among modern Confucian merchants like Eiichi Shibusawa (often referred to as the father of Japanese capitalism) and Kazuo Inamori (widely recognized as the sage of management in Japan). They strived to model sages or buddhas, demonstrating profound virtues and promoting ethical values to society (Chou et al., 2017). By 2019, Inamori’s Seiwajyuku, a non-profit management school, attracted approximately 15,000 East Asian business leaders aiming to integrate sage and buddha wisdom into modern business practices (Official Website of Kazuo Inamori, n.d.), with his books extending his influence to a much wider audience in this culture. Such widespread buddha/sage emulation highlights an intriguing cultural phenomenon: Many in the Sinosphere are undeterred by the daunting heights of seemingly unattainable moral exemplars.

A Culturally Rich and Scientifically Rigid Approach

Evidently, ethical role modeling, though universally recognized, manifests differently in East and West. Western role modeling theories well explain “attainable role modeling” in the West yet fall short in addressing the “seemingly unattainable role modeling” prevalent in East Asia, suggesting a need for further exploration. To investigate this distinct phenomenon, researchers need to acknowledge the significant influence of culture on human thought and behavior (Agostini & Persson, 2022; Hall, 1976; Tu, 1996, 2015), along with individuals’ active engagement with cultural resources to adapt to environments as reflexive beings (Hwang, 2011). Hence, it necessitates an emic (insider’s) approach, rather than an etic (outsider’s) perspective, to grasp cultural nuances (Hwang, 2015; Morris et al., 1999) and to avoid the pitfall of imposing cultural-specific standards to other societies (i.e., easy universalism; Agostini & Persson, 2022).

Yet, despite cultural differences, humanity shares a universal mind (Shweder et al., 1998). Hence, it is crucial not to assume that each society exists in its isolated cultural bubble (i.e., lazy relativism; Agostini & Persson, 2022) but to explore the universal psychological mechanisms underlying cultural phenomena (Yeh, 2023). Accordingly, this paper adopts both cultural and theoretical lenses to probe buddha/sage emulation in East Asia, aiming to eschew the traps of easy universalism and lazy relativism. The following sections first examine the theoretical underpinnings of achievable role modeling in the West before proceeding to the perplexing yet fascinating phenomenon of seemingly unattainable emulation in East Asia.

Role Modeling Theories in the West

The self-concept is multifaceted, comprising past, present, and future selves (James, 1890). Current selves often desire to evolve into ideal future selves, thereby motivating individuals to model exemplars who embody better versions of themselves (Oyserman & James, 2011). This practice of role modeling permeates our lives. Children frequently see their parents as exemplars (Chambers, 1903; Havighurst et al., 1946), while employees often regard immediate managers or mentors as ethical role models (Brown & Treviño, 2013). This identity-based motivation for emulation can foster prosocial behavior in children (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998) and ethical conduct in workplaces (Moberg, 2000; Weaver et al., 2005).

However, the aspiration to become ideal identities through role modeling does not always lead to successful emulation (Oyserman & James, 2011). For instance, teenagers often abandon celebrity role models in late adolescence (Chambers, 1903; Havighurst et al., 1946), and managers emulating senior executives often fail to exhibit ethical leadership (Brown & Treviño, 2013). To persist in ethical role modeling, individuals need to be both “inspired by” their exemplars and “inspired to” follow their example (Osman, 2019). A lack of admiration (“inspired by”) or emulation motivation (“inspired to”) can lead to role modeling failure, as elaborated below.

Ego Threat: Dampening Admiration

Admiration for role models may wane when individuals’ self-esteem is threatened by the exemplars' perceived moral superiority. As Aristotle noted, when individuals encounter an admirable moral exemplar, they appreciate his/her virtues yet may simultaneously feel distressed about their lack of such moral excellence, causing a mix of pleasure and pain (Osman, 2019). William James (1890) further noted that under such circumstances, individuals may abandon unachievable ideal identities to protect their self-esteem, causing role modeling failure. Both Aristotle’s and James’ remarks are supported by social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) and self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987). The former indicates that comparing oneself to superior individuals (i.e., upward comparisons) can evoke negative emotions and diminish self-esteem (Martinot & Redersdorff, 2005); the latter posits that a large gap between one’s ideal and actual self is associated with depression, dejection, and low self-esteem (Higgins et al., 1986; Wells & Marwell, 1976). In essence, role modeling may falter when negative emotions triggered by ego threat overshadow feelings of admiration toward lofty exemplars.

Goal Unattainability: Dampening Emulation Motivation

Emulation motivation can wane when role models seem unattainable. As psychological literature suggests, individuals are prone to adjust or even discard their original ideals when facing overchallenging ideal identities (Osman, 2019; Oyserman & James, 2011). Experiments also show that excessive uncertainty about the attainability of an ideal identity can undermine subsequent efforts (Oyserman & James, 2011). These findings are supported by goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990) and expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964). The former asserts that overly ambitious goals can deter motivation; the latter suggests that the perceived infeasibility of an objective may weaken motivation. Thus, the perception of the unattainability of a role model can dampen the drive to emulate, potentially leading individuals to admire without the intent to mimic, or to disengage entirely from the emulation process.

In summary, ego threat and goal unattainability can undermine role modeling by impeding admiration and emulation motivation, respectively. These two factors can explain aforementioned role modeling failures, as seen in late adolescents shifting from celebrities to more relatable figures like family members or neighbors (Chambers, 1903; Havighurst et al., 1946), and in entry-level managers failing to exhibit ethical leadership through modeling senior executives (Brown & Treviño, 2013). In contrast, many East Asian ethical leaders persist in emulating nearly unattainable role models like buddhas and sages. This intriguing cultural phenomenon prompts the question of how they navigate the psychological barriers of ego threat and goal unattainability, a topic the next section will explore.

Buddha/Sage Role Modeling in East Asia

In the Sinosphere, the pinnacle of moral ideals is represented by Confucian sages, Daoist sages, and Mahāyāna buddhas within their respective philosophical traditions. Confucian sages are heralded for their moral excellence and unparalleled wisdom, as seen in the revered sage kings of ancient China featured with perfect virtue and benevolent governance (Chan, 1963; Hung, 2016). Daoist sages are esteemed for their profound virtues like deep love and humility and elusive wisdom of non-action (wu wei) (Chan, 1963). Similarly, Mahāyāna buddhas are venerated for their great compassion and ultimate wisdom (Ruben & Habito, 1985). Despite distinct characteristics, these moral exemplars share a common feature: Their exalted statuses seem nearly unattainable.

Historically, Confucian sages have been rare. Beyond sage kings in ancient China, only a select few individuals have been recognized as sages, such as Confucius and Mencius of the Pre-Qin dynasty, Wang Yangming of the Ming dynasty, and Kazuo Inamori of the modern times. Daoist Sagehood is no less challenging, with Lao Tzu’s teachings seemingly easy to grasp but hard to practice (Daodejing 70). Attaining Buddhahood also poses a formidable challenge in Mahāyāna Buddhism. While Vajrayāna Buddhism suggests the possibility of achieving Buddhahood within a single lifetime (Macpherson, 1996), Mahāyāna scriptures contend that it requires extensive efforts across three great asamkhya-kalpas, or three infinite eons (Drewes, 2021; Powers, 2017). For instance, the Buddha is said to have sacrificed his life to feed a starving tigress before achieving enlightenment (Gold, 2012). Buddhahood attainment is so challenging that since the Buddha's enlightenment over two millennia ago, followers are still awaiting Maitreya, the next buddha (Ritzinger, 2017).

Despite the incredibly slim chance of achieving Buddhahood/Sagehood, many East Asian ethical leaders have revered buddhas and sages as moral exemplars throughout history. Even sages like Confucius and Kazuo Inamori refrained from claiming the title of sage. Instead, they openly acknowledged the immense difficulty of attaining Sagehood and continuously emulated the teachings of their predecessors throughout their lives (Hung, 2016; Inamori, 2009; Tan, 2021b). Many business leaders who attended Inamori’s management school, Seiwajyuku, also recognize the formidable challenges associated with reaching a sagely state. Still, they remain undeterred in their pursuit of emulating Inamori’s example, as documented in the school's bi-monthly periodicals. It is intriguing to explore how East Asian ethical leaders manage to overcome psychological challenges such as ego threat and goal unattainability associated with such role modeling.

Inamori’s insights provide potential explanations. In his work, Inamori (2009) addressed the immense difficulty of Buddhahood attainment by setting incremental goals for this lifetime. Acknowledging the impossibility of Buddhahood attainment in this very lifetime, he focused on cultivating a more beautiful and purer soul by the end of this life. He believed that making self-improvement in the present life could accelerate Buddhahood attainment in his future lifetimes, thereby diminishing the intimidating prospect of Buddhahood. To overcome ego threats, Inamori (2009, p.116 & 119) highlighted the inherent, beautiful Buddha-nature within our hearts, thereby affirming self-worth. He said: “A person’s true self is the nature of the Buddha… Since it is the nature of the Buddha, the true self is incomparably beautiful. It overflows with virtues like love, sincerity, harmony, truth, goodness, and beauty… If we embody our true selves, we become Buddha-like, pure-hearted and pure in thought, capable only of good deeds.”

Inamori’s discourses demonstrate how East Asian ethical leaders utilize the Sinosphere's rich cultural resources, like self-cultivation and Buddha-nature, to persist in emulating buddhas and sages. Essentially, East Asian philosophies not only offer lofty moral role models but also nurture practical psychological strategies to overcome the challenges of pursuing these lofty exemplars. Inspired by Inamori’s approaches, this section delves into three key cultural resources in East Asia that help sustain the buddha/sage emulation motivation.

The Hierarchical View of Personhood

The stage goals set by Inamori mirrors the hierarchical view of personhood across three major East Asian philosophies, which bolsters the buddha/sage emulation motivation by providing a step-by-step pathway toward these exalted states. For instance, the Confucian ideal of the junzi, or gentleman, offers a more achievable goal than the lofty state of sage, forming a crucial foundation for moral leadership in East Asia (Hengda & McCann, 2022). More specifically, Confucianism delineates a progression from inferior men to gentlemen, worthies, and ultimately sages (Chan, 1963). Likewise, the Buddhist enlightenment path ranges from ordinary beings, ordinary bodhisattvas, enlightened bodhisattvas (like Guanyin), finally to buddhas (Watt, 2005). Similarly, Daoism also encourages gentlemen to practice sagely wisdom by avoiding wars to pursue Dao (Daodejing 31). This hierarchical framework offers East Asian ethical leaders more attainable intermediate goals, such as gentlemen and ordinary bodhisattvas, making the pursuit of Buddhahood or Sagehood less daunting. From a psychological perspective, this approach facilitates a self-system that accommodates current and ideal identities (James, 1890), allowing for gradual progression toward ultimate ideals.

The Cognitive Style of Dialectical and Holistic Thinking

Inamori demonstrated a dialectical thinking style by emphasizing the daunting difficulty of Buddhahood attainment and the extremely beautiful Buddha-nature dwelling within all humanity. The cognitive style of dialectical thinking is prevalent in East Asia (Nisbett, 2003), which can support the motivation for buddha/sage emulation through the paradox of becoming and being. For instance, Soto Zen teaches that we are already buddhas (Phelan, 1996), reconciling the inherent difficulty of achieving Buddhahood. The seeming paradox of a buddha striving to become a buddha can be understood through the concept of Buddha-nature. As “sleeping buddhas” with dormant Buddha-nature, ordinary beings pursuing Buddhahood to awaken this Buddha-nature eventually transform into “awakened buddhas” (Situpa & Nyinche, 1996). This dialectical perspective mirrors Zhou Dunyi's Confucian view in the “Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate” (Taijitu Shuo), where the dynamic interplay of movement and tranquility symbolizes the fusion of being and becoming, merging “is to be” with “ought to be” into a unified whole. Similarly, Wang Yangming also claimed that all are sages while encouraging the pursuit of Sagehood (Instructions for Practical Living 313, 165). Recognizing oneself as essentially a buddha or sage in the making, with potential yet to be fully realized, helps diminish ego threats and perceived goal unattainability, thereby enhancing the buddha/sage emulation motivation.

Furthermore, Inamori also demonstrated a holistic thinking style by placing this transient life within the context of an endless journey toward Buddhahood. Such a holistic cognitive approach, as another key feature of East Asian culture, often views the world as an interconnected whole (Nisbett, 2003), offering a potential transcendence beyond challenges posed by buddha/sage emulation. For instance, Zhang Zai in Confucianism depicted Heaven, Earth, human beings, and all things as a universal family (Tu, 1989). Daoism also emphasizes this interconnectedness through the analogy of the mother–child relationship between Dao and all beings (Daodejing 52). Likewise, Buddhism underscores the dissolution of subject and object and the nonduality of samsara and nirvana (Loy, 1988). As Weiming Tu (1989) pointed out, the East Asian worldview is featured with the “continuity of being.” This holistic perspective reduces the perceived difficulty of achieving Buddhahood/Sagehood by unifying seemingly unreachable buddhas/sages and ordinary beings into an interconnected wholeness. In a similar vein, it can transcend the vast temporal gap between our current selves as ordinary beings and future selves as buddhas/sages with an understanding that both belong to a continuous whole. Thus, the journey toward Buddhahood/Sagehood is seen not as an isolated endeavor but as part of a broader, interconnected process, facilitating the buddha/sage emulation motivation.

The Concept of Inner Goodness

Inamori’s notion of Buddha-nature reflects the belief of inner goodness across the three major East Asian philosophies, addressing challenges posed by buddha/sage emulation through multiple ways. In Confucianism, Mencius and Wang Yangming posited that all humans inherently possess a benevolent nature (Mengzi 6A:2; Instructions for Practical Living 255). Daoism also teaches that every person is endowed with inherent virtue by Dao (Daodejing 51; Xu, 1990). Similarly, Mahāyāna Buddhism asserts the universal Buddha-nature, indicating everyone’s potential to attain Buddhahood (the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch 3:12).

This belief in innate goodness bolsters the pursuit of Buddhahood/Sagehood by reducing potential ego threats and perceived goal unattainability. Precisely, knowing that one’s inner goodness is no different from buddhas’ and sages’ (the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch 3:12; Instructions for Practical Living 255) not only enhances self-esteem but also empowers self-efficacy for the pursuit of Buddhahood/Sagehood. Yet, the concept of inner goodness is not merely a cognitive belief; it reflects our deep-seated yearning to resume our true nature and attain the ultimate good through the pursuit of Buddhahood/Sagehood. As vividly pointed out by Dogen, the founder of Japan's Soto Zen school, this inherent desire for goodness is like a duck’s natural inclination to return to water (Phelan, 1996). Mencius also highlighted human beings’ natural tendency toward goodness (Mengzi 6A:6). Similarly, Lao Tzu noted people’s inherent respect for Dao and its virtues (Daodejing 51). Recent scientific findings support this intrinsic aspiration for goodness by validating morality as an intrinsic psychological need (Prentice et al., 2019) and observing empathy in three-month old infants (Davidov et al., 2021). These research results echo the philosophical perspective that humanity is inherently attuned to flourish in the realm of “faith,” featured with an intrinsic yearning for transcendence and a profound pursuit of self-perfection (Panikkar, 1999). Hence, in East Asian philosophies, everydayness is not only a departure but also a journey returning to morality and spirituality (Tu, 1981).

In summary, the seemingly unattainable buddha/sage emulation by many East Asian ethical leaders is deeply ingrained in the rich cultural traditions of the Sinosphere. By utilizing their cultural heritage, these ethical leaders overcame challenges like ego threat and goal unattainability to sustain their emulation motivation. However, current research has yet to systematically explore this phenomenon. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by examining the cultural resources and psychological mechanisms that empower these East Asian ethical leaders to persistently strive for seemingly unachievable ideals.

Methods

This study sets out to explore how and why some East Asian ethical leaders can persist in seemingly unattainable buddha/sage role modeling. Given the limited prior research in this area, a qualitative approach was chosen for its flexibility and potential to uncover novel ideas (Yin, 2017). Specifically, qualitative case studies are ideal for answering “how” and “why” questions, as opposed to surveys, which are better suited for “what,” “who,” “where,” and “how many” questions (Yin, 2017). Case studies allow for analytic generalization from a select few cases, elucidating social science principles by generalizing lessons learned from cases. In contrast, surveys are used for statistical generalization based on large, representative samples, often to investigate the prevalence of a phenomenon. Accordingly, this study used a case study approach to explore the factors that sustain buddha/sage emulation among East Asian ethical leaders, instead of a survey to determine the extent of this practice in East Asia. The case study method involved three main steps: case selection, data collection, and data analysis, as detailed below.

Case Selection

Aiming for analytic generalizations, this study used a purposeful sampling strategy (Suri, 2011) to identify information-rich cases pertinent to buddha/sage emulation. The focus was specifically on business leaders from Seiwajyuku because they are known for their aspiration to emulate sages/buddhas, aligning with the study's objective. Seiwajyuku in Taiwan was contacted for candidate recommendation because Taiwan is recognized for its preservation of traditional Sinosphere culture and exemplifies a representative case in East Asian cultural studies (Hsieh, 2000; Yin, 2003). Initial recommendations from Seiwajyuku in Taiwan were complemented by snowball sampling, i.e., leveraging the social networks of interviewees to pinpoint further candidates (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). By employing a multiple-case study method for external validity (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2017), this research determined the final number of cases based on the principle of theoretical saturation, i.e., continuing the interview until no new relevant information was obtained (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Three criteria guided the selection: (1) recognition as ethical leaders who embody and disseminate moral values (Brown & Treviño, 2006); (2) aspiration to emulate buddhas and/or sages; (3) acknowledgment of the seemingly unattainable nature of their role models. Verification processes of ethical leadership, including stakeholder interviews and literature reviews, reduced the initial pool from 30 to 27 candidates. Further assessment on their emulation goals and perceptions of unattainability resulted in 25 ethical leaders committed to pursuing buddha/sage emulation despite its immense difficulty. These ethical leaders, aged from their 40s to 70s and comprising 6 females and 19 males, predominantly held executive roles such as chairperson, CEOs, or general managers. They represented diverse industries including electronics, accounting, consulting, interior design, food, and courier services. Their companies varied in size from small businesses to large corporations with thousands of employees.

Data Collection

Data for this study were gathered mainly through in-person, semi-structured interviews. The interview questions were open-ended and aimed to discern whom these ethical leaders view as their exemplars, whether they perceive these ideals as extremely challenging to reach, and how they manage to strive toward these seemingly elusive role models. Questions included: “Who are your role models?” “Why do you aspire to emulate them?” “How difficult is it to model them?” “Why didn’t the seeming unattainability of your exemplars deter you from role modeling?” “What motivates you to pursue such challenging role models?”.

The research team recorded the interviews in their entirety and transcribed them word-for-word to ensure the reliability of the data. Further, two researchers (one holding a Ph.D. in psychology and the other an undergraduate student in business administration) meticulously examined the extensive interview transcripts to identify discourses elucidating how these leaders sustain their efforts in buddha/sage role modeling. These identified texts were then compiled into a database for subsequent data analysis (Yin, 2017).

Data Analysis

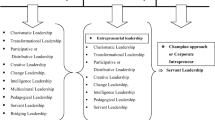

The research team conducted thematic analysis of the rich data collected from interviewed East Asian ethical leaders through a coding process involving open coding, theme generation, and dimension aggregation (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initially, three coders majoring in business administration independently labeled recurring discourse to create first-order codes (psychological strategies). These first-order codes were then grouped into second-order themes (psychological motivations) and finally consolidated into third-order dimensions (motivating approaches). To ensure data reliability, meetings were held to resolve differences among coders through extensive discussions. A subsequent review of the data led to the analysis of zero-order data for a more detailed understanding of the psychological tactics. Additionally, considering the pivotal role of cultural identity in leadership and organizations (Tu, 1996, 2015), the team analyzed the influence of East Asian cultural resources on these strategies. A Ph.D. in psychology oversaw the entire analysis process. Lastly, a subset of interviewees reviewed the research findings to validate analysis results. They concurred with the findings of this study, thereby enhancing the credibility of the study results. The data structure and codes are presented in Fig. 1.

Results

Analysis results reveal that all the 25 East Asian ethical leaders use certain psychological strategies to cope with ego threats and perceived goal unattainability stemming from buddha/sage role modeling. Remarkably, they not only mitigate demotivating factors but also draw on motivators such as self-improvement, altruism, and life purpose. Some even leverage beneficial environmental influences, including societal norms and social support, to sustain buddha/sage emulation. Table 1 presented the definitions of their strategies, the cultural resources involved, and psychological mechanisms underlying each strategy.

Addressing Demotivating Factors

To address challenges in buddha/sage role modeling, interviewed ethical leaders mitigate ego threats with rebalancing and surpassing strategies, and counteract goal unattainability through hope and temporal strategies, as detailed below.

Tackling Ego Threat

To address ego threats, some interviewed leaders adopt the rebalancing strategy aimed at reducing the perceived gap between themselves and their role models, while others utilize the surpassing strategy to transcend social comparison with their exemplars.

Rebalancing Strategy

Ego threats in unattainable emulation often arise from the stark discrepancy between role models and learners. To minimize this gap, some interviewees use the psychological tactics of external attribution, self-affirmation, and universal goodness.

Frist, the tactic of external attribution involves recognizing not only personal qualities but also circumstantial factors in the moral excellence and business success of exemplars. For example, a CEO stated, “To achieve huge success, you need the right time, the right place, and the right people. Many conditions must align.” This approach reflects East Asians’ holistic thinking, which emphasizes contextual over individual factors (Nisbett, 2003). It also helps avoid the fundamental attribution error, where personal factors are overemphasized at the expense of environmental influences in evaluating others (Ross, 1977). Additionally, making external attribution of others’ achievements can help restore one’s self-esteem (Blaine & Crocker, 1993). Accordingly, by acknowledging the role of external influences, this tactic narrows the perceived gap between individuals and their role models, thus reducing ego threats.

Second, the tactic of self-affirmation involves enhancing self-worth to narrow the perceived gap with exemplars. For instance, a general manager reflected, “Of course, we may not be able to establish a company as large as Inamori’s, but we believe that our company is constantly transforming and growing.” Another chairman said: “We can’t match the scales of Inamori’s corporations. However, no matter how small a company is, it has its contributions. Otherwise, it wouldn’t exist.” These reflections resonate with Confucian and Daoist teachings. Confucius emphasized that everyone has unique talents (Zong Yong 17) while Zhuangzi highlighted the concept of “the usefulness of the useless” with the example that a knotted and twisted tree survived because of its uselessness to human beings (Zhuangzi 1:7). This belief in inherent worth, irrespective of conventional success metrics, enables individuals to appreciate their own value, thus reducing ego threats. This aligns with self-affirmation theory, which posits that individuals protect their self-esteem by finding ways to enhance self-worth when their self-concept is threatened (Steele, 1988).

Finally, the tactic of universal goodness recognizes the inner virtues in all humans, fostering a sense of equality with role models. A chairman illustrated this method by stating, “Buddhism advocates equality among all beings, as everyone possesses Buddha-nature.” Confucianism and Daoism also emphasize inherent goodness in every individual. Such perspective helps dissolve the perceived disparity, thus removing ego threats. In other words, by acknowledging that they share the same inner virtues as buddhas and sages, these leaders see themselves on equal footing with their revered exemplars, thereby strengthening self-esteem and sustaining emulation motivation.

Surpassing Strategy

The perceived immense disparity between exemplars and learners stems from social comparison. To surpass social comparison, some interviewees employ the tactics of inspiring admiration, incomparable uniqueness, and nondualistic identities.

First, the tactic of inspiring admiration involves a conscious decision to admire, respect, and appreciate these role models rather than to compare oneself to exemplars, thereby preventing ego threats. As one CEO expressed, “The achievements and qualities of these exemplars inspire my admiration. I aspire to follow their examples.” Similarly, another chairman stated, “I greatly appreciate those who demonstrate such great love.” This approach echoes Confucius’ advice: “When we see men of worth, we should think of equaling them” (Analects 4:17; Legge, 1861), and Lao Tzu’s observation: “The good are the teachers of the not-so-good” (Daodejing 27; Muller, 2021), highlighting the instructive role of virtuous individuals in guiding others toward goodness. Given that admiration for exemplars contributes to role modeling efforts (Osman, 2019), these leaders sustain buddha/sage emulation motivation by focusing on admiration rather than social comparison.

Second, the tactic of incomparable uniqueness acknowledges individual uniqueness, rendering social comparisons with exemplars inappropriate. As one general manager said: “It’s not that they are so outstanding, and I am so incompetent. Everyone’s background is different. Everyone encounters different situations and has different lessons, destiny, and life journey. There’s no hierarchy, just what suits you. Therefore, you really can’t make such comparison.” Another general manager remarked, “Everyone has a different hand of cards. Don’t envy the good cards others hold; see what you can do with the cards in your hand.” A chairman, quoting Lao Tzu’s saying that all things come to being and flourish (Daodejing 16), stated that “Each individual, distinct and independent, has their own path to cultivate and flourish within Dao. Hence, in society, everyone, regardless of profession, shapes their unique journey.” Similarly, Confucius acknowledged that different paths and unique journeys ultimately lead toward a common successful outcome (I Ching—Xi Ci II 5:1) while the Lotus Sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism teaches that different paths to enlightenment eventually converge into the same final destination—Buddhahood. This inclusive approach echoes psychological findings that emphasizing uniqueness boosts self-esteem (Maslach et al., 1985). By negating social comparison, these ethical leaders eliminate the perceived gap with exemplars, thereby mitigating ego threats associated with unattainable role models.

Finally, the tactic of nondualistic identities involves dissolving the boundary between oneself and exemplars, thereby transcending social comparison. For example, while acknowledging the immerse difficulty of Buddhahood attainment, a chairman stated, “Buddha is actually within each of us.” Likewise, another chairperson claimed, “We are all buddhas. We can become transmitters and practitioners of Buddha’s thoughts, so we are buddhas.” Another chairman added, “Don’t measure yourself by the present, measure yourself by the future. Therefore, I see the Buddha as the future me, I am the future Buddha… Actually, everyone is a buddha.” This notion reflects the Buddhist concept of non-self, which views the self as empty and subject to change (Chu & Vu, 2022; Fry & Vu, 2023; Vu & Burton, 2022). It also resonates with Wang Yangming’s assertion that “the people filling the street are all sages'” (Wang, 2014), reflecting the East Asian philosophical concept of the “continuity of being,” where all individuals and things are seen as interconnected and evolving parts of a larger whole (Tu, 1989). By dissolving the distinction between themselves and exemplars, these ethical leaders nullify social comparison, thereby reducing ego threats and bolstering their emulation motivation.

Tackling Goal Unattainability

To counter the demotivation from perceived unattainability of Buddhahood/Sagehood, these ethical leaders adopt the hope strategy and the temporal strategy to ease the discomfort associated with the immense difficulty of attaining Buddhahood/Sagehood, as detailed below.

Hope Strategy

To mitigate the demotivation stemming from unattainable Buddhahood/Sagehood, interviewees inspire hope from three avenues. As posited by hope theory, hope occurs when one aims for a goal, believes in one’s ability to achieve it, and finds ways to reach it (Snyder et al., 2002). These three aspects of hope (goal orientation, agency thinking, and pathway thinking) are echoed in the tactics used by interviewees.

First, the tactic of stage goals involves setting more attainable, intermediate objectives to restore a sense of hope. As one chairman said, “Go as far as you can… Inamori also said, make your soul purer than when you were born. I think this is something we can pursue.” One general manager stated, “You’re on a journey toward your life’s ideal. It’s a series of steps, one after another. By taking the initiative to move forward, you’re on the right path.” This step-by-step approach allowed them to maintain hope despite the distant ultimate goal. It echoes the hierarchical personhood views in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, which advocate progressive paths toward Buddhahood/Sagehood. Consequently, these ethical leaders stay hopeful on their journey toward seemingly unattainable role models.

Second, the tactic of agency thinking involves drawing on the concept of Buddha-nature to bolster confidence. As one general manager said, “Everyone possesses Buddha-nature. Therefore, we should have confidence that we too can achieve Buddhahood.” Another interviewee said, “Everyone has Buddha-nature. Even though the realm of buddhas is extremely high, people still have the chance to reach it.” As previously mentioned, Confucianism and Daoism also underscore the inner goodness as the foundation for achieving Sagehood. As predicted by hope theory, agency thinking ignites hope.

Finally, the tactic of pathway thinking involves instilling a sense of hope by finding methods toward the aim. One general manager said, “Finding the right teacher and the right method is crucial.” Another interviewee stated, “The Buddha has already awakened, and we have not yet. We have not awakened because we are still clouded by many afflictions, such as greed, anger, and ignorance. We need to continually disperse the clouds, dispel the obstacles and doubts, and elevate our minds. Only by elevating our minds can we gradually reach the state of enlightenment.” In short, although Buddhahood seems unattainable, they have found methods for enlightenment. Confucianism also highlights self-cultivation as the path to Sagehood (Gardner, 2007; Tan, 2023b). Likewise, Daoism advocates “self-so-ing” (ziran) as the approach to achieving Dao (Sellmann, 1987). As predicted by hope theory, pathway thinking inspires hope.

Temporal Strategy

The path to Buddhahood/Sagehood seems daunting not only because of the tremendous efforts required but also due to the immense time commitment involved. To combat this challenge, some leaders develop distinct temporal perspectives to dissipate despair associated with this lengthy pursuit, including cultivating a present mindset, appreciating time, and transcending time. This aligns with time perspective theory, which posits that time perspectives influence motivation and behavior (Kauffman & Husman, 2004; Kooij et al., 2018).

First, the tactic of the present mindset focuses on striving in the now, rather than worrying about attaining Buddhahood/Sagehood. One general manager said, “I constantly remind myself that it’s more important to make today better than yesterday, and tomorrow better than today… We should focus on how to do things well in the present. That’s what matters.” Another interviewee concurred, “I take today’s tasks very seriously and do my best to live in the present. That’s the right way to live. You don’t have to keep pondering about what you want to achieve… Yes, it’s good to have lofty goals, but you have to start from where you are and gradually work your way up, step by step.” Mindfulness studies revealed that focusing on the present moment helps alleviate distress (Coffey & Hartman, 2008). The Buddhist concept of mindfulness resonates with Confucian and Daoist teachings. While the Confucian notion of jing (maintaining full, respectful attention to others) illustrates the social application of mindfulness (Tan, 2021a), the Daoist practice of non-action contributes to mindful leadership (Tan, 2023a). Accordingly, this present mindset alleviates concerns about the perceived unattainability of Buddhahood/Sagehood, thereby mitigating demotivation associated with such emulation.

Second, the tactic of time appreciation addresses the frustration of the lengthy journey to Buddhahood/Sagehood through gratitude. A chairman expressed, “Why does it take three asamkhyeya-kalpas to attain Buddhahood? It is because we need to solidify our foundations. Without a solid foundation, how can we attain enlightenment? Therefore, the process is to nurture us into buddhas. We should be grateful for having this lengthy period of time to achieve Buddhahood.” Hence, he is not disheartened by the extensive duration but instead, appreciates the ample time he has to refine himself into ultimate ideals. The importance of gratitude has been underscored not only in Buddhism (Emmons & Shelton, 2002) but also in Confucianism (Van & Long, 2021; Yeh & Bedford, 2003). Research indicates that gratitude can foster hope (Overwalle et al., 1995) and optimism (Emmons & Crumpler, 2000). Hence, this tactic addresses the challenge of perceived goal unattainability through gratitude, thereby sustaining buddha/sage emulation motivation.

Lastly, the tactic of time transcendence involves acknowledging the illusory nature of time, thereby transcending the perceived lengthy journey to Buddhahood/Sagehood. One general manager mentioned, “The notion of three asamkhyeya-kalpas is a test of your faith. Time is just an illusion.” A chairman added, “In reality, attaining Buddhahood happens in an instant.” Another chairman explained, “What the Buddha wanted to break is the concept of space and time. One can become a buddha or a devil in a single thought. Becoming a buddha in one thought means that we only need to focus on the present moment to do good deeds. Buddhism teaches that cause and effect originate from the same source. When you sow a cause, the effect has already been established.” These notions align with perspectives in Mahāyāna Buddhism, as Nāgārjuna said in the “Knowledge of the Middle Way,” “Because of things there is time. Apart from things how can time be? Even things do not exist. How much less can time exist?” (Miyamoto, 1959). By viewing time as an illusion, these ethical leaders feel undeterred by the distant attainment of Buddhahood. Interestingly, Zhuangzi also suggested the malleable nature of time, stating that meeting a great sage after ten thousand generations could feel as instantaneous as meeting this paragon in a single morning or evening (Zhuangzi 2:12). From a psychological perspective, the perceived reduction in temporal distance to a goal can enhance its attractiveness and thus motivate action (Husman & Lens, 1999). Hence, by transcending the concept of time, these interviewees overcome the challenge of goal unattainability associated with buddha/sage emulation, thereby sustaining their role modeling motivation.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that while the three major East Asian philosophies advocate nearly unachievable ideals, they also provide abundant cultural resources that can be translated into effective psychological methods to address challenges associated with such ethical role modeling. By creatively capitalizing on these cultural resources, interviewed East Asian ethical leaders effectively tackle the challenges of seemingly unattainable buddha/sage emulation. Interestingly, in addition to addressing demotivating issues, they also amplify motivating factors for emulating lofty role models, as elucidated below.

Amplifying Motivating Factors

Qualitative analysis reveals that these East Asian ethical leaders sustain buddha/sage emulation motivation not only by resolving demotivating factors like ego threats and goal unattainability but also by enhancing motivators, including the needs for self-betterment, altruism, and life purpose. This motivating approach capitalizes on humanity’s intrinsic aspiration for goodness, a theme central to major East Asian philosophies. Hence, despite the considerable challenges associated with such emulation, all interviewees recognize its substantial benefits of fulfilling these psychological needs. This finding aligns with Weiming Tu’s (1978; p.72) observation: “Man is ‘designed’ to perform a great task in life—self-realization, which in its fullest development leads not only to peace in the world but to perfect identification with Heaven.”

Practicing Self-Betterment

These East Asian ethical leaders are not deterred by the formidable challenge of buddha/sage emulation, as they discover immediate benefits in their pursuit. For instance, such role modeling aids them in practicing self-cultivation, fulfilling the desire for self-improvement highly valued in East Asian philosophies (Fiske, 2018; White & Lehman, 2005). Additionally, self-cultivation elevates their minds and instills a sense of inner freedom, providing personal-growth feedback to reinforce their buddha/sage emulation motivation.

Self-Cultivation

A majority of interviewees clarified that while they aspire to attain Buddhahood/Sagehood ultimately in future lifetimes, their immediate goal in this lifetime is to learn from these lofty exemplars for self-improvement. Echoing this dual focus, a chairman who aims for Sagehood stated, “Why should I become the second Inamori? There’s no need to become him. By learning his spirit and philosophy, I can cultivate my character and grow my business—that’s my goal.” Likewise, another general manager mentioned that he gleans much wisdom from Confucian sages, including Confucius’s benevolence and Wang Yangming’s unity of knowledge and action, striving to apply their teachings to his life with an eye toward eventual Sagehood. Similarly, another chairman regards learning from Daoist sages not only as a progression toward Sagehood but also as a means for current personal development.

These remarks indicate that while these ethical leaders aim to evolve into sages/buddhas ultimately, they place significant value on immediate learning and character development. For example, one chairman applies the Daoist principle of moderation to curb personal desires, while another leverages the Daoist dialectical thinking style to discover hidden benefits in misfortune. This approach embraces daily improvement as essential parts of a prolonged path to Buddhahood/Sagehood, embodying the East Asian philosophy of the “continuity of being” (Tu, 1989). Thus, despite the daunting challenge of Buddhahood/Sagehood, interviewees perceive immediate benefits from utilizing these ideals as resources and inspirations for continuous self-improvement.

Personal-Growth Feedback

Interviewees further noted that self-cultivation practice based on buddha/sage emulation leads to highly rewarding personal growth. A chairman mentioned, “I feel happier than before. My worries and difficulties haven’t disappeared, but their duration has shortened.” Another chairman stated, “You will attain freedom through such emulation.” Another participant elaborated, “You will experience the liberty of the spirit and the beauty of life.” Their personal growth echoes Mencius’ teachings that moral virtues not only please our minds but also radiate throughout our entire beings (Mengzi 6A:7; 7A:20). Psychologically, such personal growth offers positive reinforcement, further motivating self-cultivation efforts through buddha/sage emulation. As goal-setting theory indicates, positive feedback encourages individuals to persist in their endeavors (Locke & Latham, 1990).

Prioritizing Altruism

Apart from achieving self-betterment, these ethical leaders identify another benefit in buddha/sage emulation—the enhancement of their altruistic actions. Altruism, the motivation to assist others, is deeply ingrained in human nature for communal advancement (Haidt, 2012) and features the three major East Asian philosophies (Chan, 2008; Lee et al., 2013; Marques, 2010, 2012). Influenced by this cultural value, many interviewees emphasize caring for employees and contributing to society. Furthermore, buddha/sage emulation enhances their capabilities to help others, which often results in gratitude from the helped. This cycle of benevolent actions and positive interpersonal feedback is elaborated below.

Benevolent Action

Interviewees emphasize that their emulating buddhas/sages is not solely for self-improvement but also for the welfare of others. One general manager stated, “Initially, it helps you improve gradually, making your soul purer and better. Eventually, you can help others improve as well.” Another interviewee added, “If possible, apply their teachings in our lives. We can even aim to become influential and bring about positive impacts on our employees and possibly their families and offspring, passing such spirit down generation by generation.” A chairman applies the Daoist principle of non-action to foster corporate growth and employee well-being. Therefore, despite the immense challenge involved in buddha/sage role modeling, these leaders persist in such emulation to foster effective altruism.

Interpersonal Feedback

These ethical leaders often receive positive feedback for their altruistic actions, which further fuels their motivation for buddha/sage emulation. One chairman noted, “As you steer toward altruism, you’ll gradually experience the joy of feedback. Your motivation to continue in this direction will be reinforced by both external and internal feedback, such as others’ gratitude or the joy you feel from making those decisions.” This observation echoes Mencius’s notion that those who love others are often loved back (Mengzi 4B:28). As goal-setting theory indicates, positive feedback motivates individuals to persist in their efforts (Locke & Latham, 1990). Thus, the encouraging responses from the helped bolster these ethical leaders’ commitment to buddha/sage emulation.

Pursuing Life Purpose

Beyond self-betterment and effective altruism, these ethical leaders acknowledge that seemingly unreachable buddha/sage emulation provides a clear trajectory toward a purposeful life. Psychologically, a purpose in life can infuse meaning, ignite passion, and drive dedication toward long-term goals, thereby fulfilling our inherent need for meaningfulness (Frankl, 1976; Steger, 2018). The pursuit of a meaningful purpose has been a core teaching across the three major East Asian philosophies: Confucius emphasized the aspiration for Dao (Analects 4:9; 7:5), Lao Tzu taught that all eventually return to Dao (Daodejing 16), and Dogen in Buddhism viewed our return to Buddha-nature as an innate human inclination (Phelan, 1996). These ethical leaders also caution that a life without such meaningful purpose would be plagued with distress, dissatisfaction, and remorse. Their drive for meaningful direction and regret prevention enhances their motivation for buddha/sage emulation, as expounded below.

Meaningful Direction

Despite the daunting challenge of buddha/sage emulation, many interviewees view this path as essential for their life’s purpose. As one chairman stated, “I admit it is very difficult, but the point is that we should strive toward the right path. The essence of being human lies in this path.” This path involves two purposes: cultivating oneself and helping others. As stated by interviewees, their purpose in life is to elevate character and expand business to assist others, resonating with the Confucian and Daoist ideals of “inner sage and outer king” and the Buddhist bodhicitta teaching of “enlightening oneself to salvage others” (Rinpoche, 1999).

Such purposeful pursuit contributes to a meaningful existence, as one chairman said, “Every day, I ask myself what I can do to help others. This instills my life with meaning and gives me motivation to come to the office.” Another general manager added, “I feel very fortunate to know the endeavor I want to devote my life to.” Their remarks align with logotherapy, which posits that meaningfulness fuels long-term dedication (Frankl, 1976). Since buddha/sage role modeling endows interviewed leaders with a meaningful life purpose, they manage to persist in such emulation, regardless of the immense challenges.

Interestingly, these ethical leaders perceive buddha/sage emulation not as a final destination, but rather as a continual guiding journey. As one director said, “I regard my ideal models as the North Star, serving as a spiritual guide in my profession.” Another general manager added, “It’s a journey, not a time-bound goal. Cultivation is an ongoing process with no endpoint. Therefore, the moment you initiate progress, you’re on the right track.” Their perspectives align with psychological literature that distinguishes purposes, which provide directions, from goals, which have definite endpoints (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). By focusing on progress rather than a definitive destination, they transform the formidable goal of Buddhahood/Sagehood into a meaningful life purpose, thereby transcending the immense challenge of such lofty pursuits.

Regret Prevention

Some interviewees stated that a life without meaningful emulation would lead to future regrets, thereby intensifying their motivation for buddha/sage modeling. As a general manager said, “People should give themselves a chance, otherwise they would drift further from the Buddha. Without Buddhist wisdom, they will suffer a lot from sorrow and anxiety.” Another chairman added, “You would regret it if you didn’t take action.” Another general manager remarked, “I feel very fortunate because I found such a lofty role model to learn from. The saddest thing, in my opinion, is to lack such a role model.” Their perspective echoes ancient East Asian wisdom: Confucius warned that a refusal to learn in youth leads to a lack of abilities in older age (Kongzi Jiayu 9:2), whereas the Buddha likened those failing to lead a virtuous life in early years to old cranes struggling to catch fish (Dhammapada 11). These ethical leaders’ remarks also resonate with psychological studies that identify regret as a potent motivator, driving individuals to make decisions that avoid future remorse (Bjälkebring et al., 2015). Similarly, regulatory focus theory suggests that a prevention focus motivates behavior (Higgins, 1998).

In summary, to persist in seemingly unattainable buddha/sage modeling, these East Asian ethical leaders leverage their cultural resources not only to address demotivating factors (ego threat and goal unattainability) but also to amplify motivators (self-betterment, altruism, and life purpose). Intriguingly, they further assimilate positive environmental influences to reinforce this emulation, as elucidated below.

Assimilating Environmental Factors

Analysis results indicate that the interviewees also sustain their aspiration toward challenging role models through environmental forces like social norms and support. While human beings universally adhere to social norms and need social support (Hooker et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2023), these tendencies are particularly pronounced in East Asian cultures characterized by collectivism, relationalism, and interdependence (Hofstede, 1984; Hwang, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). These ethical leaders utilize this cultural inclination to fuel their buddha/sage emulation aspirations, as expounded below.

Honoring Social Norms

Despite the seemingly unattainability of ultimate ethical exemplars in East Asia, buddha/sage emulation is strongly encouraged in the Sinosphere. This social expectation and subsequent positive social feedback sustain these ethical leaders’ motivation for such emulation.

Social Expectation

Some interviewees attribute their motivation for buddha/sage emulation to social expectations in their formative years. As one chairman reminisced, “In my childhood, teachers emphasized moral education and won my respect. I got genuinely interested in Confucian teachings they shared.” Another interviewee stated, “As a child, I asked my father what religion to declare in my school survey. He told me to write down Confucianism. I have since consistently done so.” These narratives illustrate the significant role of cultural norms in the Sinosphere in shaping their emulation journey. Psychologically, the adherence to social norms is driven by a desire for social acceptance (Chudek & Henrich, 2011). It is noteworthy that East Asia harbors not only these three major teachings but also other norms, such as a highly competitive achievement orientation (Yi, 2013). This implies that these ethical leaders engage in wise selection among diverse social norms, resonating with Confucius’ approach to conforming with discernment (Analects 9:3).

Social Feedback

These ethical leaders found that adherence to the social norm of buddha/sage emulation often results in the embodiment of moral values and positive social feedback, reinforcing their motivation for such role modeling. As one chairman said, “If you cultivate a pure mind and high moral standards by learning from sages, you will gain respect from others and live truly freely.” This idea echoes Confucius’ view that moral behavior leads to societal esteem (Analects 13:20) and aligns with psychological findings that affirmation from others encourages conformity to social norms (Zhang et al., 2023).

Harnessing Social Support

Some interviewees highlight the crucial role of social support in enhancing their motivation for buddha/sage emulation. Interestingly, they draw strength not only from their immediate friends but also from distant exemplars.

Immediate Support

Facing the daunting task of buddha/sage emulation, some ethical leaders seek support from their immediate circles. A general manager shared her constructive interactions with entrepreneur friends, assisting her in remaining on this path. She said, “Having a community or group like ours is beneficial.” Another interviewee also pointed out, “In my darkest times, my wife’s steadfast adherence to Buddhism revived me and transformed my life. I am also grateful to friends who introduced Buddhism to me and encouraged me to change.” Their views echo Confucius’ advice that we should make beneficial friends like the honest, the sincere, and the learned (Analects 16:4). Similarly, the Buddha also said that a monk with admirable people as friends will pursue the noble path (Upaddha Sutta SN 45.2). According to self-determination theory, satisfying the need for relatedness aids value internalization, leading to enduring moral motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Thus, social support from family and friends provides these ethical leaders with the strength to persevere in their Buddha/Sage emulation.

Remote Support

Some interviewees draw encouragement from texts depicting their exemplars grappling with similar challenges. A chairman said, “I believe both buddhas and sages are ideals we can pursue. Even Confucius admitted his imperfections.” Another interviewee cited Inamori’s words that he would not stop trying just because he could not achieve it. They felt less isolated knowing their admired exemplars encountered similar difficulties. Interestingly, Mencius also found solace in the hardships faced by ancient sage kings, accordingly viewing misfortunes as a necessary preparation for making influential societal contribution afterward (Mengzi 6B:15). This perspective aligns with self-compassion research, which posits that understanding others’ similar struggles fosters our connection with them, thereby liberating us from isolated loneliness (Neff, 2023). Hence, acknowledging similar challenges in their role models helps these ethical leaders to persevere toward their lofty ideals.

In conclusion, these East Asian ethical leaders persist in seemingly unattainable buddha/sage emulation by addressing demotivators, amplifying motivators, and assimilating environmental factors. These strategies can also be categorized into two overarching themes: regulating self-focus and goal perspective. From the perspective of self-focus, these role models appear daunting due to the ego-defense mechanism. To counter this issue, these ethical leaders shift their self-focus from ego defense to self-improvement, other-orientation, or collective identity, thus enhancing emulation motivation by fulfilling their needs for self-betterment, altruism, or conformity to social norms. In terms of goal perspective, the frustration associated with seemingly unreachable exemplars often arises from a strong desire to achieve certain objectives. To address this challenge, they recalibrate their goal perspective by reframing individual objectives into shared ones or purposeful directions, thereby enhancing emulation motivation by drawing strength from social support or by meeting the need for life purpose. These research results are presented in the model in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The impact of culture on social phenomena is profound, yet its influence is often underestimated in social science (Agostini & Persson, 2022). As seen in managerial research, religion and spirituality are relatively underexplored despite their significance in shaping ethical standards in many cultures (Parboteeah et al., 2007, 2009; Van Buren et al., 2019). For instance, while there is a growing interest in the influence of Confucian values on East Asian ethical leadership (e.g., Tan, 2023b; Yuan et al., 2023), ethical role modeling in this culture still cannot be fully elucidated by existing role modeling theories. To address this research gap, this study investigated how and why certain ethical leaders in East Asia persist in modeling after seemingly unattainable sages and buddhas. Research findings resonate with the notion that business ethics in non-Western cultures are often intertwined with religion and spirituality (Van Buren et al., 2019) as interviewed ethical leaders capitalize on East Asian cultural resources to formulate effective psychological strategies for sustaining buddha/sage emulation motivation. Intriguingly, the psychological mechanisms underlying these culturally influenced strategies are universal, suggesting potential applicability to other societies. This section will detail this study’s theoretical contributions, practical implications, research limitations, and future directions.

Theoretical Contributions

This study makes theoretical contributions to ethical leadership literature by investigating the “how” and “why” behind seemingly unattainable ethical role modeling prevalent in East Asia. First, the millennia-old East Asian tradition of modeling seemingly unattainable exemplars has been underexplored in social science. Given that role modeling theories in the West fall short of elucidating the above cultural phenomenon in the Sinosphere, this study adopted an inductive approach to uncover effective psychological strategies utilized by interviewed East Asian ethical leaders to sustain this cultural practice. Rather than investigating how prevalent such emulation is among East Asian ethical leaders, this research focused on elucidating the social science principles behind this phenomenon through drawing an analytic generalization from select cases (Yin, 2017). Accordingly, this study broadens our understanding of how seemingly unattainable role modeling supports ethical leadership in the Sinosphere.

Second, this study deepens our understanding of how culture influences ethical role modeling in East Asia. It reveals that while the three major East Asian philosophies present challenging role models, they also provide a rich array of cultural resources that support and sustain such emulation practices. These philosophies not only help mitigate demotivators like ego threats and goal unattainability but also enhance motivators by inspiring intrinsic aspirations for goodness such as self-improvement, altruism, and purposeful pursuit. The social inclination fostered by these cultural teachings also bolsters buddha/sage role modeling efforts through social norms and support. This analysis uncovers the sophisticated interplay between culture and agency in shaping ethical leadership through seemingly unattainable role models in the Sinosphere. By employing an emic approach that acknowledges cultural nuances, this study avoids the trap of easy universalism often associated with an etic perspective (Agostini & Persson, 2022).

Lastly, this research elucidates the universal psychological mechanisms of buddha/sage emulation in East Asia. Although many of the cultural resources utilized to sustain such emulation are unique to the Sinosphere, the underlying psychological mechanisms are in line with established social science theories. For instance, hope theory (Snyder et al., 2002), developed in a Western context, effectively explains certain psychological strategies employed by these East Asian ethical leaders to tackle the challenge of perceived goal unattainability. By blending cultural richness with scientific rigor, this research unveils universal psychological principles within a culturally specific phenomenon (Yeh, 2023), thereby transcending the pitfall of lazy relativism (Agostini & Persson, 2022) and broadening our theoretical understanding of this distinct cultural phenomenon.

Practical Implications

This study’s findings offer insights for cultivating ethical leadership in East Asia. First, given that Western ethical principles might not always find resonance within East Asian contexts (von Weltzien Hoivik, 2007), integrating East Asian ethical role models into ethical leadership education in the Sinosphere is essential. Second, while the lofty ideals of buddhas and sages are inspirational, they could seem overwhelmingly daunting even to some East Asians. The cultural resources and psychological principles identified in this research can guide ethical leadership development in this culture, making these ideals more accessible. Finally, the study’s findings, while rooted in East Asian contexts, draw on established psychological theories, thereby suggesting broader applicability. These insights have the potential to aid individuals from various cultural backgrounds in navigating the challenges of pursuing lofty role models.

Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study offers unique perspectives into the pursuit of unattainable role models in the East Asian tradition. However, it also presents some limitations that signal opportunities for future research.

First, this study seeks to elucidate how and why certain ethical leaders in East Asia can sustain their motivation to model after seemingly unattainable paragon, rather than determining the prevalence of this emulation across the Sinosphere. Although the tradition of modeling after such paragons is deeply rooted in this culture, the extent of its practice among ethical leaders in this region remains to be quantitatively assessed with a broader sample in future research.

Second, while this study interviewed ethical leaders from Taiwan, a Confucian society often seen as representative of the Sinosphere (Hsieh, 2000; Yin, 2003), the findings may not encapsulate all psychological strategies and cultural resources that help sustain buddha/sage emulation. Therefore, future research can consider conducting additional case studies in other Confucian societies to uncover more insights to deepen our understanding of buddha/sage emulation in the Sinosphere.

Third, the qualitative findings of this study have not been quantitatively validated yet. Subsequent studies can develop and validate scales to investigate the appropriateness of strategy classifications, the effectiveness of the strategies, and potential interactions among them. It would also be intriguing to examine whether different personality types prefer distinct psychological strategies.

Fourth, this study does not distinguish between ethical leaders based on their chosen paragons, such as Confucian sages, Daoist sages, or Mahāyāna buddhas. Future research could investigate potential differences in strategies adopted by ethical leaders pursuing different exemplars. Nevertheless, in East Asian societies, some ethical leaders follow both Confucianism and Buddhism (Yü, 2021). A Daoist ethical leader in this study also pointed out the interconnectedness of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Thus, any future research aiming to differentiate emulation strategies among Confucian Sagehood, Daoist Sagehood, and Buddhahood should approach the task with nuanced understanding and careful consideration.

Finally, this study focuses on the East Asian context, and the applicability of its findings to other cultures is yet to be determined. Future research could extend this investigation to different cultures, providing comparative analyses and evaluating the model’s relevance in broader contexts.

In conclusion, while lofty exemplars may seem formidable when perceived as within sight but beyond reach, East Asian culture reimagines esteemed paragons as being beyond reach but within sight. This perspective shift conveys an inspiring message that the sky is the limit, encouraging a boundless pursuit of excellence and moral elevation, as demonstrated in this study and throughout East Asian history. As touchingly articulated by Sima Qian, the great historian of ancient China, Confucius was “like a towering mountain that people look up to, like the great Dao that people follow. Although I cannot reach such heights, I aspire to them” (Shiji—House of Confucius; Parker, 2023).

Data availability

The interview data in this study contains potential personal sensitive information and has been anonymized in accordance with the requirements of the Ethics Committee of National Taiwan Normal University. In line with the principles of participant consent and privacy protection, the data will not be shared publicly. The interview excerpts cited in the article have been de-identified to ensure the privacy of participants while reflecting key support points for the research findings.

References

Agostini, B., & Persson, S. (2022). Revisiting the connection between context and language from Hall to Jullien: A contribution to a real intercultural dialogue. Management International, 26(6), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.7202/1095756ar

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kuritines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (pp. 45–103). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bandura, A., & McDonald, F. J. (1963). Influence of social reinforcement and the behavior of models in shaping children’s moral judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(3), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044714

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods and Research, 10(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ1102063

Bjälkebring, P., Västfjäll, D., Svenson, O., & Slovic, P. (2015). Regulation of experienced and anticipated regret in daily decision making. Emotion, 16(3), 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039861

Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1993). Self-esteem and self-serving biases in reactions to positive and negative events: An integrative review. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard (pp. 55–85). Springer.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2013). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1769-0

Chambers, W. G. (1903). The evolution of ideals. The Pedagogical Seminary, 10(1), 101–143.

Chan, G. K. Y. (2008). The relevance and value of Confucianism in contemporary business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(3), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9354-z

Chan, W.-T. (1963). A source book in Chinese philosophy. Princeton University Press.

Chou, S. C., Cheng, B.-S., Hwang, K.-K., & Yu, S.-H. (2017). Discovering the psychological mechanism of Confucian missionary entrepreneurs to transcend the dilemma between instrumental and value rationality. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies (in Chinese), 47, 305–370. https://doi.org/10.6254/2017.47.305

Chu, I., & Vu, M. C. (2022). The nature of the self, self-regulation and moral action: Implications from the Confucian relational self and Buddhist non-self. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(1), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04826-z

Chudek, M., & Henrich, J. (2011). Culture-gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.03.003

Coffey, K. A., & Hartman, M. (2008). Mechanisms of action in the inverse relationship between mindfulness and psychological distress. Complementary Health Practice Review, 13(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533210108316307

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Davidov, M., Paz, Y., Roth-Hanania, R., Uzefovsky, F., Orlitsky, T., Mankuta, D., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2021). Caring babies: Concern for others in distress during infancy. Developmental Science, 24(2), e13016. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13016

Drewes, D. (2021). The problem of becoming a bodhisattva and the emergence of Mahāyāna. History of Religions, 61(2), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1086/716425

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1998). Prosocial development. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 701–778). John Wiley & Sons.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

Emmons, R., & Crumpler, C. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.56

Emmons, R. A., & Shelton, C. M. (2002). Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 459–471). Oxford University Press.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fiske, S. T. (2018). Social beings: Core motives in social psychology (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Frankl, V. E. (1976). Man’s search for meaning. Pocket.

Fry, L. W., & Vu, M. C. (2023). Leading without a self: Implications of Buddhist practices for pseudo-spiritual leadership. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05416-x

Gardner, D. K. (2007). The four books: The basic teachings of the later Confucian tradition. Hackett Publishing Company.

Gold, J. C. (2012). Does the Buddha have a theory of mind? Animal cognition and human distinctiveness in Buddhism. In J. W. Haag, G. R. Peterson, & M. L. Spezio (Eds.), The Routledge companion to religion and science (pp. 520–528). Routledge.

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor.

Havighurst, R. J., Robinson, M. Z. R., & Dorr, M. (1946). The development of the ideal self in childhood and adolescence. The Journal of Educational Research, 40(4), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1946.10881515

Hengda, Y., & McCann, D. P. (2022). The ideal of junzi leadership and education for the common good. In S. Rothlin, D. McCann, & M. Thompson (Eds.), Dialogue with China: Opportunities and risks (pp. 79–88). World Scientific.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60381-0

Higgins, E. T., Bond, R. N., Klein, R., & Strauman, T. (1986). Self-discrepancies and emotional vulnerability: How magnitude, accessibility, and type of discrepancy influence affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.5

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Hooker, E. D., Zoccola, P. M., & Dickerson, S. S. (2018). Toward a biology of social support. In C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez, L. M. Edwards, & S. C. Marques (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 658–668). Oxford University Press.

Hsieh, J. (2000). East Asian culture and democratic transition, with special reference to the case of Taiwan. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 35, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852100512130

Hung, R. (2016). A critique of Confucian learning: On learners and knowledge. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1084220

Husman, J., & Lens, W. (1999). The role of the future in student motivation. Educational Psychologist, 34, 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3402_4