Abstract

Dual-Doppler lidar has become a useful tool to investigate the wind-field structure in two-dimensional planes. However, lidar pulse width and scan duration entail significant and complex averaging in the resulting retrieved wind-field components. The effects of these processes on the wind-field structure remain difficult to investigate with in situ measurements. Based on high resolution large-eddy simulation (LES) data for the surface layer, we performed virtual dual-Doppler lidar measurements and two-dimensional data retrievals. Applying common techniques (integral length scale computation, wavelet analysis, two-dimensional clustering of low-speed streaks) to detect and quantify the length scales of the occurring coherent structures in both the LES and the virtual lidar wind fields, we found that, (i) dual-Doppler lidar measurements overestimate the correlation length due to inherent averaging processes, (ii) the wavelet analysis of lidar data produces reliable results, provided the length scales exceed a lower threshold as a function of the lidar resolution, and (iii) the low-speed streak clusters are too small to be detected directly by the dual-Doppler lidar. Furthermore, we developed and tested a method to correct the integral scale overestimation that, in addition to the dual-Doppler lidar, only requires high-resolution wind-speed variance measurements, e.g. at a tower or energy balance station.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It has long been known that turbulent fluid motion exhibits patterns of self-organization, so-called coherent structures. Robinson (1991) listed various shapes of structures occurring in a flat-plate boundary layer (FPBL) at low Reynolds number: near-wall low-speed and high-speed streaks, i.e. alternating regions in which the streamwise fluid velocity is increased or decreased compared to its mean value and that are elongated in the direction of the mean flow; ejections and sweeps, i.e. intermittent, rapid movements of the fluid outward from the wall in the low-speed regions or towards the wall in high-speed regions, respectively; as well as various vortical structures shaped like quasi-streamwise vortices, arches, hairpins or horseshoes. Adrian et al. (2000) combined earlier findings in a hairpin vortex packet paradigm in which they assume shear-induced spanwise vortex filaments close to the wall being lifted and stretched into hairpin-shaped structures that can self-replicate, form packages and grow throughout the boundary layer. According to this model, low-speed streaks form due to the fluid motion between one or several successive hairpin legs, the vortical motion of which causes the ejection, while sweeps occur due to the inverse process in between, and in front of, the hairpin vortex packets. The model was substantiated with direct numerical simulations (Zhou et al. 1999; Adrian and Liu 2002).

The atmospheric boundary layer, in contrast, is a high Reynolds number flow, in which turbulence is created from both shear and buoyancy. Here, three kinds of structures have been observed (Agee 1984; Young et al. 2002): surface-layer streaks comparable to FPBL streaks in shear-dominated flows (Hommema and Adrian 2003; Newsom et al. 2008), horizontal rolls reaching through the whole boundary layer in moderately convective situations (Etling and Brown 1993; Hartmann et al. 1997), and cell-shaped updrafts in very unstable situations (Feingold et al. 2010). These structures appear as well in turbulence-resolving large-eddy simulations (LES, Moeng and Sullivan 1994; Khanna and Brasseur 1998; Kim and Park 2003; Hellsten and Zilitinkevich 2013).

Here, we focus on surface-layer streaks, which we also call ‘structures’ or ‘coherent structures’ throughout the text since they occur in repetitive patterns, even though it should be kept in mind that they might be just the footprints of larger-scale hairpin vortices.

Streaks are particularly important for subgrid-scale parametrizations in mesoscale models due to their large contribution to the Reynolds stress tensor. Using the notation \(u^\prime \), \(v^\prime \) and \(w^\prime \) for the streamwise, spanwise and vertical (i.e., wall-normal) turbulent velocity components, it is known that usually \(\overline{u^\prime w^\prime }<0\) in the surface layer, thereby generating turbulence kinetic energy due to shear (Stull 1988; Adrian 2007). This is the result of the prevalence of ejections (\(u^\prime <0\), \(w^\prime >0\)) and sweeps (\(u^\prime >0\), \(w^\prime <0\)), the latter of which occur more often but with less intensity than the former (Lin et al. 1996; Kim and Park 2003).

Traditionally, these structures have been investigated with in situ measurements of wind speed, temperature or humidity (Thomas and Foken 2007; Zhang et al. 2011), however, their spanwise and wall-normal extent and statistical distribution cannot be measured in this way. Arrays of in situ sensors were able to capture small-scale processes (Inagaki and Kanda 2010; Thomas et al. 2012), but are difficult to extend over hundreds of metres. Dual-Doppler lidar methods seem to provide a valuable supplement here, since they allow the measurement of the complete two-dimensional wind field with a spatial resolution of a few tens of metres and a time resolution of the order of 10 s on planes of several km\(^2\) in size. It has been shown that surface-layer streaks can be detected with horizontal dual-Doppler lidar scans (Newsom et al. 2008; Iwai et al. 2008) and a recent study by Träumner et al. (2014) derived their length scales depending on stability and background wind speed. However, the limited time and spatial resolutions due to scan duration and the extent of the lidar pulse lead to severe inherent averaging in the resulting wind fields (Stawiarski et al. 2013). The influence of these processes on the detected turbulence structures cannot be determined with independent in situ measurements, and we can expect that small-scale structures in particular, which are on the order of or smaller than the lidar averaging scale, are insufficiently detected.

To assess the quality of surface-layer coherent structure detection in dual-Doppler lidar data, we developed a lidar simulation tool that is able to perform virtual dual-lidar measurements in turbulence-resolving boundary-layer simulation data from LES. We performed virtual synchronized horizontal scans with parameters comparable to real Doppler lidars in LES data with varying shear. On both the resulting dual-lidar and original LES wind fields we applied three common structure detection techniques: a correlation length algorithm, a wavelet analysis and a clustering method. We compared the distributions of the resulting streak length scales and thereby determine which techniques are applicable for reliable results. Further theoretical investigations allowed us to explain the results and, in the case of correlation lengths, to develop a technique for length scale correction.

2 The Dataset

Horizontal dual-Doppler lidar measurements are made with two lidars synchronously scanning an overlap area at low elevation. In the region where data from both lidars are present the horizontal wind field can be deduced using a change of basis (Newsom et al. 2008). The resulting fields have a spatial resolution on the order of the lidar pulse width and a time resolution given by the lidar scan duration.

Although coherent structures are usually visible in the resulting streamwise wind-field component, two aspects complicate an interpretation of the results: firstly, the lidar measurements contain considerable smoothing due to the inherent spatial averaging resulting from the lidar pulse width and the duration and uneven sampling of the scanning area, and secondly, validation of measurement results is difficult because no other instrument provides wind measurements with comparable frequency and range.

However, since the averaging processes involved in measurements with solid-state based Doppler lidars are mathematically well described (Frehlich et al. 1998; Frehlich 2001), it is possible to simulate Doppler lidar measurements in high-resolution boundary-layer wind-field data, e.g. from LES. We employ this method for two virtual lidars with synchronized scan patterns and retrieve the horizontal wind field from the resulting virtual dual-Doppler measurement data. The data can be subsequently analyzed for coherent structures. On the other hand, the same methods can be applied to the original LES data. The comparison yields an insight into the applicability of the well-established methods of structure detection to dual-Doppler lidar data and allows us to test methods of correction.

2.1 Simulation of Doppler Lidar Measurements

Stawiarski et al. (2013) developed a lidar simulation software tool that works as a Doppler lidar forward operator and enables virtual Doppler-lidar measurements in a simulated boundary layer. We make use of an upgraded version of the software, the computational principle of which is summarized below.

In a given three-dimensional LES wind-vector data grid, the virtual lidar position, its measurement characteristics (pulse width, range gate length etc.) and scan pattern are prescribed as external parameters to the simulator, which in turn computes position, orientation and scanned-through region for every range gate of the lidar beam at every timestep. From the geometric information a weighted average is computed for each wind-field component by interpolating the data grid on the range gate and taking the lidar-dependent weighting functions into account (Frehlich et al. 1998; Frehlich 2001). The radial wind component is subsequently obtained by projecting the averaged wind vector on the lidar beam.

For a dual-Doppler lidar simulation, the scan patterns of two virtual lidars are synchronized. The horizontal wind field can be obtained from a retrieval algorithm, which reassembles the data from both lidars and finds the most probable horizontal wind vector on a Cartesian grid. Here, we use the retrieval method of minimizing a cost function from Stawiarski et al. (2013) that is based on Newsom et al. (2008).

2.2 The LES Data

PALM is a parallelized LES model developed by Raasch and Etling (1991) and Raasch and Schröter (2001), with governing equations that use the Navier–Stokes equations in a Boussinesq approximation. The subgrid scales are parametrized according to Deardorff et al. (1980) with a gradient transport approach and Monin–Obukhov similarity is prescribed below the lowest computational grid level, including the calculation of the friction velocity \(u_*\). Coriolis effects are included for a prescribed latitude of \(\varphi =55^\circ \) north. For this study, we simulated four 30-min wind-field datasets with PALM version 3.9 with geostrophic background wind \(u_{G} = 0\), 5, 10, and 15 m s\(^{-1}\) (cf. Table 1). Although we cannot expect streaky structures in the calm situation, the dataset was analyzed to depict the development of structure length scales with the background flow, and to assess the detection methods in principle in a situation where time series analysis is unattainable. All datasets were computed on a grid with 5 km by 5 km horizontal area and a spatial grid constant of 10 m in all directions throughout the boundary layer; the time resolution was 1 s. The simulations were performed for a dry atmosphere over a flat terrain with a roughness length of \(z_0 = 0.15\) m. Since LES cannot reliably reproduce turbulence on scales of 2–3 times the grid length, special care must be taken in the interpretation of the smallest length scales, which may not necessarily give a realistic representation of the surface layer.

At the horizontal borders, cyclic boundary conditions were assumed, which implies an infinite, periodically repeating model domain. The simulated boundary layers were initialized with a stable profile of the potential temperature, \((\text {d}\theta /\text {d}z)_\mathrm{initial} = 0.08\) K m\(^{-1}\) below \(z=1200\) m, and driven by the prescribed geostrophic background flow and a fixed kinematic surface heat flux of \(\overline{w^\prime \theta ^\prime }_0 = 0.03\) K m s\(^{-1}\) for \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\) and \(\overline{w^\prime \theta ^\prime }_0=0.23\) K m s\(^{-1}\) in the calm situation (cf. Table 1). In the vertical, Dirichlet boundary conditions were imposed on the wind-field variables and for the pressure at the top boundary, whereas the other variables had Neumann boundary conditions (cf. Table 2). The data output started after a spin-up time of 1 h, at which time the simulation showed fully developed turbulence. During spin-up, random perturbations with small amplitudes were initially imposed on the horizontal velocity field to trigger turbulence until the TKE exceeds a threshold value. With fully developed turbulence, all simulated boundary layers became unstable, with stability decreasing as the background wind speed decreased. The resulting scaling parameters are summarized in Table 1, and Fig. 1 shows the mean profiles of wind speed, potential temperature and vertical heat flux. A detailed description of the PALM-model is available online (http://palm.muk.uni-hannover.de).

The resulting LES datasets were used for virtual dual-lidar measurements. To compare the virtually measured wind fields with the original LES fields, the LES had to be interpolated to the virtual lidar measurement height of 15 m. Figure 2 shows the emerging streaky coherent structures in the shear-driven flows. The solely convective case, in contrast, exhibits open cell structures in the w-component, which are however not visible in u or \(\upsilon \). In the following analysis, structure detection results from this dataset will be indicated with the shorthand ‘LES’.

Snapshots of the turbulent wind-field component \(u^\prime \) in the mean wind direction at 10 m height in the four LES datasets. \(u_\mathrm{G} = \{0, 5~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1},\;10~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1},\; 15~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1}\}\) from left to right. The axes \(x_0\) and \(y_0\) are aligned with the geostrophic wind vector

Furthermore, to separate the influence of the lidar scan duration from other lidar error sources such as spatial averaging and time undersampling, the LES wind fields at the measurement height were averaged over the time of a scan duration. This dataset is denoted as ‘LESAVG’. In contrast, the dataset obtained from virtual dual-Doppler measurement and retrieval is denoted ‘LIDAR’.

2.3 The Dual-Doppler Lidar Data

The parameters for the two virtual Doppler lidars were chosen to match those of the Doppler lidars at the Institute for Meteorology and Climate Research at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (Röhner and Träumner 2013). Their lasers with wavelengths 2023 and 1617 nm have a pulse width (FWHM) of 370 and 300 ns in time domain, respectively, corresponding to a spatial pulse width \(\Delta r\) of 55.5 and 45.0 m (Frehlich et al. 1998). With a pulse repetition frequency of 500 and 750 Hz, a 10-Hz measurement frequency can be achieved with random velocity estimation errors \(<\)0.2 m s\(^{-1}\) (Stawiarski et al. 2013). Compared to the pulse widths, the LES grid constant of 10 m is small, which is the necessary condition for the simulator to produce realistic results.

The virtual lidars, as shown in Fig. 3, were positioned at (\(x=2500\) m, \(y=0\) m) and (\(x=5000\) m, \(y=2500\) m) in the original LES axes to obtain a beam intersection angle close to \(90^\circ \) in the overlap region, thereby reducing the propagated single lidar error (Stawiarski et al. 2013). During the scan, their measurement height was \(z=15\) m and their elevation was kept at zero whereas the azimuth varied, scanning a \(90^\circ \) sector each. The scan time \(T_0\) (which determines the angular velocity \(\omega _0\)) and the range gate length \(\Delta p\) were chosen following the optimization procedure described in Stawiarski et al. (2013), which allows maintaining errors as small as possible, depending on the background wind speed. Here, the lower limit of the range gate length was set to 55 m, corresponding to the higher of both \(\Delta r\) values. The resulting scan parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Each virtual lidar performed continuous zero-elevation scans in each of the four LES datasets for the full 30 min. Subsequently, the retrieval algorithm was applied, which yielded the horizontal wind field on a Cartesian grid with a grid constant of \(\Delta p\) and a time resolution of \(T_0\). Figure 4 shows snapshots of the retrieval wind fields at the same times as in Fig. 2. The lidar-measured fields exhibit the same qualitative structures, albeit considerably smoothed.

Snapshots of the turbulent wind-field component \(u^\prime \) in mean wind direction from the virtual dual-lidar retrieval at the same time steps as in Fig. 2. \(u_\mathrm{G} = \{0,\, 5~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1},\, 10~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1},\, 15~\mathrm{m~s}^{-1}\}\) from left to right. The axes \(x_0\) and \(y_0\) are aligned with the geostrophic wind vector

The horizontal wind fields of the three data types (LES, LESAVG and LIDAR) from all four LES datasets were converted into their streamwise and spanwise components, and rotated in the mean wind direction at measurement height derived from the original LES dataset, therefore ‘x’ and ‘y’ indicate the streamwise and spanwise axis, and u and v the streamwise and spanwise component, respectively.

To check consistency, the LIDAR wind fields were compared with the LESAVG wind fields for each retrieval timestep after spatial interpolation of the LESAVG fields to the dual-lidar retrieval grid. The results are shown in Fig. 5: the differences are represented by an approximately Gaussian distribution with a negligibly small bias. The standard deviation increases with turbulence production from both buoyancy (\(u_\mathrm{G}=0\), high surface heat flux) or shear (\(u_\mathrm{G}\gg 0\)), and assumes values between 0.47 and 0.79 times the standard deviation of the respective LES velocity components (cf. Table 1). When comparing the LIDAR dataset directly with the LES data, using a nearest-neighbour approach to interpolate the LIDAR data to the LES time axis, \(\sigma \) assumes values between 95 and 115 % of those from comparison with the LESAVG data. For \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\), \(\sigma _\mathrm{LIDAR,LES} > \sigma _\mathrm{LIDAR,LESAVG}\) and increasing with the wind speed. For \(u_\mathrm{G}=0\), it is smaller, since the large-scale uniform u and v regions can be well resolved with lidar.

The distributions of u show a slight positive skewness, which is caused by the negative skewness of \(u_\mathrm{LESAVG}\) due to the uneven spatial coverage of narrow low-speed streaks embedded in large high-speed regions, which is averaged out in \(u_\mathrm{LIDAR}\) (cf. Figs. 2, 4). The effect occurs less pronouncedly in the v distributions as well.

Difference between dual-lidar retrieval and time-averaged LES wind-field components, \(f_\mathrm{LIDAR}-f_\mathrm{LESAVG}\) for \(f=u,\upsilon \) after interpolation of the LIDAR dataset on the LES grid. \(\mu \) and \(\sigma \) are the mean and standard deviation of the distributions, computed directly from the dataset, r is their correlation coefficient

3 Identification of Coherent Structures

To quantify the accuracy of coherent structure detection in dual-lidar data, we applied three common structure length scale detection techniques to the LIDAR, LES and LESAVG datasets.

Additionally, we recorded virtual time series at 2601 virtual towers of 15 m height in the LES data, which were evenly distributed over the horizontal LES area, by linearly interpolating the u and v wind-field components to their position. For comparative results from tower data, those time series were evaluated with the same methods as the spatial data, and the time scales converted to length scales by multiplication with \(\overline{u}\) at the measurement height, (cf. Table 3) for all datasets with \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\), since here \(\sigma _u< 0.2~\overline{u}\) and therefore Taylor’s hypothesis can be applied (Willis and Deardorff 1976; Stull 1988).

3.1 Correlation Length Approach

The integral length scale or correlation length \(L_{f,x}\) is a measure of the distance in the x-direction over which a field f can be considered correlated with itself. In the x- and y-directions, it is defined as

and

where \(\mathbf {e}\) is the unit vector in a given direction, and \(r_f\) the autocorrelation function,

where

is the turbulent deviation of f from its mean and \(\sigma ^2_f\) is the variance of f. Here, \(\langle \cdot \rangle _\mathbf {x}\) indicates the average over the variable \(\mathbf {x}\) in the argument. Integral scales can, under ergodic conditions, be computed from spatial data or time series, where Taylor’s hypothesis must be applied in the latter case (Stull (1988)). The size of the dataset determines the statistical accuracy (Wyngaard 2010, Chap. 2.4).

The integral length scale is a common tool used to characterize the structure of boundary-layer wind fields (Lenschow and Stankov 1986) and has been applied to surface-layer wind fields obtained with dual-Doppler lidar, e.g. by Newsom et al. (2008).

We computed the integral length scales for the LES, LESAVG and LIDAR dataset wind-field components u and \(\upsilon \) in both streamwise (x) and spanwise (y) directions. The discretization of the data on the grids required a conversion of the integrals into sums, \(\int \, \mathrm{d}x \rightarrow \sum \, \Delta x\), where \(\Delta x\) is the respective grid spacing given by \(\Delta p\) (cf. Table 3) for the LIDAR data and \(\Delta x=10\) m for the LES and LESAVG data. Furthermore, we used the approximation of Lenschow and Stankov (1986) to accommodate the finite data,

where the integral is only executed up to the first zero crossing of \(r_f\). Here, the ensemble averages used in Eqs. 2 and 3 and the variance were computed from the spatial averages in the 2D data of the respective timestep.

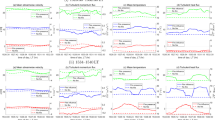

Distribution of the integral scales L of the u (streamwise) and v (spanwise) wind-field components in streamwise (x) and spanwise (y) direction as a function of \(u_\mathrm{G}\) for the four datasets LIDAR (white box, solid outline), LESAVG (grey box), LES (black box) and the virtual tower time series (white box, dashed outline). The boxes range from the 25th percentile (\(Q_1\)) to the 75th percentile (\(Q_3\)), the centre lines mark the median (\(Q_2\))

The resulting lengths from the virtual towers, after conversion to spatial scales, are correlation lengths in the streamwise direction, while the spanwise component is inaccessible with this method. The results for all four datasets are shown in Fig. 6.

The different datasets show a similar length scale development with increasing wind speed. The integral scales measured by the lidar are quantitatively similar to those measured under unstable conditions (Träumner et al. 2014). The LES scales seem to be noticeably limited to values about 2–3 times the LES grid resolution, which could be expected (cf. Sect. 2.2), but this effect only influences the spanwise analysis. Whereas the lidars severely overestimate the integral length scales, the tower measurements exhibit the opposite behaviour and underestimate the integral scales. In contrast, the LESAVG dataset length scales do not differ considerably from the LES dataset length scales, which indicates that the time averaging inherent in the lidar data has only a minor contribution to the full lidar error. The dual-lidar deviation is therefore the sole result from spatial averaging and temporal undersampling in the dual-lidar data. This behaviour can be understood with the help of the following considerations.

3.1.1 Time Series Results

If the dataset was perfectly ergodic, the time average of the wind-field components at every virtual tower would be identical to the average over the full dataset. However, the standard deviation of the temporal means \(\sigma \left( \overline{f}^T\right) \) of the virtual towers reaches values between 0.14 and 0.3 times the variance of the original fields \(\sigma _f\) in the LES datasets for \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\) and an even higher percentage for \(u_\mathrm{G}=0\) (cf. Table 4).

Lenschow et al. (1994) showed that

for \(T \gg \tau \) where T is the time duration of the measurement, \(\tau \) is the temporal integral length scale and \(\sigma ^2_f\) is the variance of the full signal f.

The variation of the time series has to be taken into account in the integral length scale computation: we have to distinguish between the full temporal autocovariance \(\rho _\mathrm{full}(\Delta t)\) with a time shift \(\Delta t\) from averaging over the complete dataset, and the time series covariance \(\rho _\mathrm{tower}(\mathbf {x},\Delta t)\) computed from the subset of data at point \(\mathbf {x}\),

with the respective turbulent field components

Careful computation shows that

where

This means that the autocovariance, averaged over different towers, will usually be underestimated. The variance between time-series averages at the towers is a measure for the magnitude of the underestimation. Equation 8 holds as long as we can assume that

which can be assumed for long time series. From Eq. 8, it follows that, for the autocorrelation function

since

for all \(\Delta t\) with \(\rho _\mathrm{tower}(\mathbf {x},\Delta t) < \rho _\mathrm{tower}(\mathbf {x}, 0)\), as can be shown by a Taylor series expansion of the left hand term in Eq. 12 in the parameter \( (\Delta f^\prime (\mathbf {x}))^2\). This means that the tower underestimates the autocorrelation function for almost all \(\Delta t\), and consequently the integral length scale is underestimated as well.

To correct the results it would be necessary to replace \(f^\prime _\mathrm{tower}\) with \(f^\prime _\mathrm{full}\) and to average over the full dataset in the computation of the integral scale, however, in field campaigns, the full spatial and temporal average is usually inaccessible. Alternatively, using time series of longer duration will decrease \(\Delta f^\prime \) and improve the results when ergodicity can be assumed (Tennekes and Lumley 1972).

3.1.2 Dual-Lidar Results

The overestimation of scales by the dual-lidar system can be explained by the inherent spatial and temporal averaging. Frehlich (1997) showed that the structure function of the lidar-measured radial velocity underestimates that of the real radial velocity up to large displacements along the lidar beam due to the moving average induced by the lidar pulse. A similar argument is proposed here: assume that the dual-lidar spatial averaging in the lidar plane can be described by a convolution of the real wind-field components with a smoothing function s,

The function s is normalized, so that Eq. 13 also holds for \(f^\prime _\mathrm{lidar}\) and \(f^\prime \). When inserted into the definition for the autocorrelation, Eq. 2, we find that

where

and ‘\(*\)’ indicates the convolution.

In contrast to Frehlich (1997), the averaging process is not only defined by the mathematically well-described lidar-beam averaging (Frehlich et al. 1998; Frehlich 2001), but is rather a result of the beam averaging, the data aggregation and weighting in the retrieval process and the time averaging and undersampling. A precise relation is therefore unattainable, however, we can assume that the smoothing function s is approximately constant around the grid-cell centre up to a distance of the retrieval data radius and subsequently drops to zero. It should be noted that the assumptions of horizontal homogeneity and isotropy for s are only approximations.

To model the averaging effects, we use a one-dimensional window function approach for s,

and

with \(\mathbf {x} = (x,y)\) and the Dirac distribution \(\delta \). The functions \(s_x\) and \(s_y\) are used for the computation of the length scales \(L_{f,x}\) and \(L_{f,y}\), respectively. As a consequence, the averaging perpendicular to the direction of the autocorrelation lag is neglected. The length scale \(l_0\) is half the diameter of the window function and works as a fit parameter to estimate the averaging scale of the dual-lidar results, \(2l_{0}\) will therefore hereafter be called the effective lidar averaging scale. The model Eqs. 16 and 17 allow an analytical computation of the overestimation,

where \(\sigma ^2_f\) denotes the spatial variance of the field component f. The overestimation becomes a function of the parameter \(\xi =2l_{0} L_f^{-1}\), i.e. the ration of effective lidar averaging scale to the actual integral length scale, with \(L_{f,\mathrm{lidar}} L_f^{-1} \rightarrow 1\) for \(\xi \rightarrow 0\) and \(L_{f,\mathrm{lidar}} L_f^{-1} \rightarrow \infty \) for \(\xi \rightarrow \infty \).

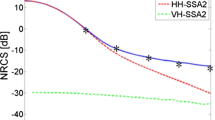

Figure 7 shows the overestimation factors of Fig. 6 as a function of the LES integral scale together with the theoretical results from Eq. 18. We find that, regardless of the background wind speed, \(\xi \) and thereby the effective averaging scale \(2l_{0}\) is approximately constant in the spanwise direction (black symbols), whereas a slight increase with the wind speed can be observed in the streamwise direction (white symbols) which is due to advection during the scan time. For the spanwise scales, \(2l_0 \approx 3 \Delta p\), whereas for the streamwise scales the value of \(2l_0\) goes up to 10 \(\Delta p\). Furthermore, for all datasets with \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\) the effective lidar averaging scale is identical for the u and v components.

Lidar overestimation factor of integral length scales as a function of the high-resolution integral scales, normalized with the lidar grid resolution. The data points are located at \(Q_2(L_\mathrm{LIDAR})/Q_2(L_\mathrm{LES})\) and \(Q_2(L_\mathrm{LES})/\Delta p\) with black symbols for \(L_y\) scales and white symbols for \(L_x\) scales. The error bars range from \(Q_1(L_\mathrm{LIDAR})/Q_3(L_\mathrm{LES})\) to \(Q_3(L_\mathrm{LIDAR})/Q_1(L_\mathrm{LES})\) on the ordinate and \(Q_1(L_\mathrm{LES})/\Delta p\) to \(Q_3(L_\mathrm{LES})/\Delta p\) on the abscissa, where \(Q_n\) indicates the nth quartile. The lines are the theoretical results from Eq. 18 for varying \(q=2 l_0/\Delta p\)

Despite the strong overestimation, Eq. 18 suggests that the scales can be corrected if the full spatial variance \(\sigma ^2_f\) of the wind-field component is known. Notably, the first equality of Eq. 18 is a result of the convolution model, Eq. 13, and holds for any normalized smoothing function s.

In field measurements, the spatial variance \(\sigma _f^2\) can be approximately obtained from time series measurements, e.g., a sonic anemometer placed at the measurement height. For a comparable result, we take \(\sigma _u^2\) and \(\sigma _{v}^2\) to be the median variance computed from the virtual tower measurements, and thereby derive the corrected dual-lidar integral length scales for \(f=u,\,v\) in the four datasets,

The results are shown in Fig. 8. The correction method on average removes the overestimation bias and notably reduces the spread of the length-scale distribution for all datasets with \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\), even if the length scales approach the lidar resolution. The remaining bias for \(u_\mathrm{G}>0\) is in most cases approximately \(0.5\Delta p\) and therefore could be an artefact of the length-scale computation algorithm. The correction fails for calm situations, when tower measurements are inadequate for spatial variance measurements. In an alternative correction method one would have to measure the spatial variance with high resolution, e.g. using a large anemometer array. Figure 8 furthermore shows a correction of the LESAVG length scales, using Eq. 18 with the averaging scale \(2 l_0 = T_0 \overline{u}\) and \(L_f\) taken from the LES data. The method removes the overestimation, but over-corrects when the LES scales are very small. This can possibly be explained with the insufficient representation of turbulence by the LES for scales approaching the grid resolution.

Corrected distribution (Eq. 19) of the integral scales L of the u (streamwise) and v (spanwise) wind-field components in streamwise (x) and spanwise (y) direction as a function of \(u_\mathrm{G}\) for the four datasets. The corrections were applied for the LIDAR and LESAVG datasets. Colours and ranges are as in Fig. 6

3.2 Wavelet Analysis

Wavelet analyses have been widely used to extract coherent structures from temperature, wind field and humidity fluctuation time series (Collineau and Brunet 1993a, b; Thomas and Foken 2007; Zhang et al. 2011; Zeeman et al. 2013). A wavelet is a localized function \(\varphi ((t-b)a^{-1})\) in time (or space) t which is scaled with a factor a and shifted to the position b. When certain mathematical criteria are fulfilled, the set of all wavelets created by varying a and b is a basis in the vector space of square integrable functions (Louis et al. 1998), i.e., the original time series g(t) can be written as a linear combination of the wavelets in the set. The associated coefficients

are the projections of the time series on the wavelet \(\varphi ((t-b) a^{-1})\), i.e. they are a measure of the agreement between g and \(\varphi \) around the point b when \(\varphi \) is scaled with the factor a.

For coherent structure extraction, such wavelets are useful when they resemble the shape of the desired structure, e.g. an ejection-sweep pattern. Alternatively, transitions from ejections to sweeps, which are odd sections of g(t), are detected at the zero-crossings of the wavelet coefficients of an even wavelet.

To apply the wavelet analysis to the datasets, one-dimensional subsets were taken from the two-dimensional wind-field components for each timestep. In the LES datasets, one streamwise and one spanwise subset were chosen randomly for each 1-s timestep for both u and v. Since the LESAVG and LIDAR datasets comprise fewer time step, five spanwise and five streamwise subsets were selected. Additionally, the virtual tower time series of u and v in the original LES dataset for 15-m height, which were already used in the integral scale analysis, were included in the evaluation.

On all series in space and time, a wavelet analysis was performed following the methods described in Barthlott et al. (2007) and Segalini and Alfredsson (2012). First, the signal was appropriately detrended and zero-padded (Thomas and Foken 2005), then the wavelet coefficients (Eq. 20) with the WAVE wavelet,

were computed (cf. Fig. 9). The WAVE wavelet function closely resembles the ejection-sweep cycle that can be expected in the streamwise wind field u (Zhang et al. 2011; Segalini and Alfredsson 2012).

Subsequently, the wavelet spectrum or scalogram was determined,

and by integrating over all event positions b, the scalogram is a measure for the energy per wavelet. The scale \(a_0\) in which the scalogram becomes maximal determines the wavelet scale for which the series f contains the highest energy (Collineau and Brunet 1993a).

The positions of the structures were now determined at the zero-crossings of the MHAT wavelet coefficients on the dominant scale \(a_0\) with the correct slope sign. The even MHAT wavelet function (cf. Fig. 9) is the second derivative of a Gaussian function and given by

Collineau and Brunet (1993a; b) showed that the MHAT is particularly suited to detect odd events like an ejection-sweep cycle. Evaluating the MHAT coefficient only on the dominant scale implies a smoothing of the original signal g, which is useful to eliminate noise. Some authors have proposed excluding structures in which the wavelet coefficient does not exceed a certain threshold value, but we found that the choice of threshold does not significantly influence the results. Having determined the structure positions, the length of each structure was computed following Barthlott et al. (2007) as the distance from the respective zero-crossing to the following maximum in the MHAT wavelet coefficient. The resulting ramp length will be denoted by \(\Lambda ^r_{f,x_i}\) as in the case of integral scales, where f once again stands for the field component u (streamwise) or v (spanwise) and \(x_i\) is the direction of evaluation, either x (streamwise) or y (spanwise).

It should be noted that the series subjected to the wavelet analysis are either functions of time (in the virtual tower case) or of space (in the case of LIDAR, LESAVG, and LES datasets), and that therefore \(a_0,\, b\) and \(\Lambda ^r\) are given in units of time or space as well, which are obtained by multiplying the results in pixel units with the time resolution \(\Delta t\) or the spatial resolution \(\Delta x\) of the respective series. For the virtual tower time series, the streamwise spatial length scales were derived from the computed temporal length scales by multiplying with the mean wind speed of the respective time series.

Since the algorithm only works with an accuracy of one data point, a possible bias of one pixel will have a much larger effect on the LIDAR dataset (1 pixel \(= \Delta p\)) than on the LES and LESAVG datasets (1 pixel \(=\) 10 m). We therefore refine the algorithm by removing the bias in pixel units. Since the size of \(\varphi \) is proportional to a, we can assume that the average length scales detected at the dominant scale \(a_0\) will also be proportional to \(a_0\),

and consequently \(\lim _{a_0 \rightarrow 0} \Lambda ^r(a_0) = 0\). For the correction, all length scales (in pixel units, here denoted by px) were reduced by the ordinate intercept of 3.28 px of the linear fit of \(a_0 \, \mapsto \Lambda ^r(a_0)\) before converting both \(a_0\) and \(\Lambda ^r\) into units of m. For the slope we obtained a fit result of \(m_\Lambda = 2.68\).

Distribution of the wavelet ramp lengths \(\Lambda ^r\) of the u (streamwise) and v (spanwise) wind-field components in streamwise (x) and spanwise (y) direction as a function of \(u_\mathrm{G}\) for the four datasets. Colours and ranges are as in Fig. 6

The results are shown in Fig. 10. As in the case of correlation lengths, LESAVG and LES results agree well. For the streamwise direction, the time series are in good agreement with the LES results as well, whereas a slight overestimation and broadening of the distributions is detected for the LIDAR datasets, particularly for the length scales shorter than 200 m.

The bias occurring for the short ramp lengths can be explained by the spatial filtering effect of the lidar data: the scalogram part corresponding to scales a shorter than the lidar resolution is considerably damped, which leads to a shift of the maximum to higher scales (Fig. 11). However, Fig. 10 does not show a simple monotonous increase in overestimation with decreasing LES scales, which suggests that other factors influence the lidar wavelet analysis.

Using the one-dimensional averaging model of Sect. 3.1.2, Eqs. 16 and 17, the wavelet coefficients for the lidar wavelet analysis are given by

Eq. 25 implies that the wavelet and smoothing functions can be summarized in an effective lidar wavelet function \(\Phi \),

with

The function \(\Phi \) is not only a function of \((x-b) a^{-1}\), but has the additional parameter \(l_0 a^{-1}\), i.e. the relation between the effective lidar averaging scale and the wavelet scale. The influence of this parameter can be observed in Fig. 12, where the WAVE and MHAT wavelets are shown for \(a=1\) and \(b=0\) with varying \(l_0 a^{-1}\). We find that, so long as \(l_0 \le a\) the effective wavelet \(\Phi \) is practically identical to the original wavelet \(\varphi \). However, when \(l_0\) becomes larger than a, the wavelet begins to split in the centre and two localized parts develop that drift apart, their distance \(2\Delta \) increasing proportionally to \(l_0 a^{-1}\). Consequently, the desired localization of the wavelet is lost—the wavelet transform with \(b=0\) no longer contains information about the agreement of f with the wavelet around \(x=0\), but rather about the agreement of f with the split wavelet around the points \(x=\pm \Delta \). Therefore, the dual-lidar wavelet analysis is only meaningful when the phenomenon studied exhibits dominant scales larger than the lidar averaging scales. This has to be ascertained with independent, high-resolution measurements. When the condition is fulfilled, the inherent lidar smoothing is of no significance and the lidar results can be considered correct. Otherwise, the wavelet analysis fails and produces random results that are not related to the phenomenon studied. With the cut-off \(l_{0}a^{-1}\approx 1\) and the linear relation between \(\Lambda ^r\) and \(a_0\) (Eq. 24) we can determine a threshold value for \(\Lambda ^r\) under which the lidar results become unreliable,

Effective wavelets (Eq. 27) \(\Phi (x,l_0 \cdot a^{-1})\) for the WAVE (a) and MHAT (b) wavelets around \(x=0\) for varying values of \(l_{0} a^{-1}\), normalized to identical maximum values

which again depends on the factor \(q=2 l_0\Delta p^{-1}\) shown in Fig. 7. Using the values for q determined in Sect. 3.1, we find that \(\Lambda ^r_\mathrm{thresh}\Delta p^{-1} \approx 4\) for the spanwise data and \(4 \lesssim \Lambda ^r_\mathrm{thresh}\Delta p^{-1} \lesssim 14\) for the streamwise data, increasing with \(u_\mathrm{G}\). In most cases the results in Fig. 10 do not fulfill these requirements, the wavelet method is therefore useful for either larger-scale structures or higher-resolution lidars.

It should be noted that the condition \(l_{0}a^{-1}\approx 1\) can also be derived from the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem (Shannon 1949): Since the MHAT wavelet has its spectral maximum at wavenumber \(k_\mathrm{max} = \sqrt{2}/a\) (Collineau and Brunet 1993a), the required resolution to resolve this wavenumber is \(\Delta x \le 2\pi /(2k_\mathrm{max})\). Using \(\Delta x = 2l_0\), we find that \(l_{0}a^{-1} \le \pi /\sqrt{8} \approx 1.1\).

3.3 A Clustering Method

The most immediate approach for the characterization of surface-layer streaks is given by the clustering method. Here, a coherent structure is defined as the two-dimensional connected subset C of the plane in which the streamwise or spanwise turbulent wind-field component is smaller than a threshold value. The lengths \(\Lambda ^c_x\) and \(\Lambda ^c_y\) of such a structure are initially defined as the distance between the outermost points in the connected region in streamwise and spanwise direction, respectively. An additional scale correction is explained below.

The algorithm was applied to all timesteps of the LES, LESAVG and LIDAR datasets for both the streamwise and spanwise components. For each timestep and each field component, the spatial standard deviation \(\sigma \) was computed and the threshold was set to \(K=-1.5\sigma \). All clusters with length and width of more than one data pixel were included in the evaluation. The comparative results shown below were nearly insensitive to a variation of K.

Additionally, the virtual tower time series of u and v in the area at lidar measurement height were evaluated. Here, the temporal standard deviation was used for the threshold. Naturally, the time series only yielded the structure length in streamwise direction, which were again determined from the temporal lengths by multiplication with the mean wind speed.

As in the wavelet analysis, we corrected the length scales to remove single pixel errors and to ensure that the asymptotic behaviour is correct, i.e., that the area of the cluster \(A \rightarrow 0\) for \(\Lambda ^c_x, \Lambda ^c_y \rightarrow 0\). Therefore, we assumed that, on average, \(\Lambda ^c_x \Lambda ^{c}_{y}\) is proportional to A, which is true for elliptical shapes. To remove a possible bias \(\delta \) we performed a fit,

with parameters m and \(\delta \) on all data in pixel units and removed the resulting \(\delta =-0.34\) pixels before converting the length scales into units of m (Fig. 13).

Cluster area means as a function of the mean length-scale products in the u and v components of the four datasets for LIDAR (white), LESAVG (grey) and LES (black). Left Before correction. Right After correction using a fit to Eq. 29 (\(m = 0.57\), \(\delta = -0.34\)). Missing points are due to overlaps

The results are shown in Fig. 14, where it is clear that the lidar smoothing entails a significant overestimation of scales. The structure lengths in the high-resolution LES data are on average of the order of or smaller than the lidar averaging scales which makes it impossible for the lidar to detect them correctly. However, despite the small scales of the structures, the LESAVG dataset matches the high-resolution LES results well, only a displacement at higher background wind speed is apparent. This underlines the persistence of the structures, particularly in spanwise direction.

The cluster scales are measured directly and are not a statistical measure for the whole field (as the integral scales), or further smoothed (as in the wavelet case). Therefore, although they provide the most direct insight into the wind-field structure, the results cannot be corrected mathematically unless we have prior knowledge of, (i) the cluster length scale distribution in the original wind field and (ii) the original wind field’s spatial variation statistics on the effective lidar averaging scale surrounding the clusters. We must conclude that, for cluster length scales shorter than \(l_0\), the clustering algorithm is unable to provide reliable results on dual-lidar data.

Distribution of the cluster lengths \(\Lambda ^c\) of the u (streamwise) and v (spanwise) wind-field components in streamwise (x) and spanwise (y) directions as a function of \(u_\mathrm{G}\) for the four datasets. Colours and ranges are as in Fig. 6

3.4 Comparative Results

All three methods, the correlation length, wavelet and clustering algorithm, provide information on the scales of streaky coherent structures in the wind field. However, the approaches focus on different aspects, which leads to large differences between the structure length scales, the width of their distribution and their variation with the background wind \(u_\mathrm{G}\), as can be seen in Figs. 8, 10 and 14. This underlines the fact that quantitative findings about coherent structures very much depend on the respective detection technique, rather than an underlying fundamental definition. The correlation lengths decrease for higher \(u_\mathrm{G}\) in the spanwise direction of u and v, and increase with \(u_\mathrm{G}\) for the streamwise analysis of u. The correlation length is a statistical measure for the whole two-dimensional wind field and thereby unable to produce information on single structures.

The wavelet analysis detects each structure, but only after smoothing the wind field to the energetically dominant scale. The qualitative behaviour of the wavelet scales resembles the correlation length results but leads, on average, to higher length scales. Its validity is limited to structures with energetically dominant length scales larger than the lidar averaging scale.

The clustering algorithm uses no averaging or scaling, but rather directly detects ejections using a threshold approach. While giving the most direct information on each coherent structure, the small-scale structures investigated here cannot be reliably detected with this method in dual-Doppler lidar data, because the lidar averages out the small scales. This method is also limited to structures larger than the averaging scale, but here ‘structure’ means the geometrical extent of the clustered region.

The comparative overestimation of length scales in the lidar data is shown in Fig. 15. The corrected retrieval results perform best with the exception of the (uncorrectable) \(u_\mathrm{G} = 0\) datasets. The wavelet analysis shows, as expected, rather noisy results for scales smaller than the threshold length scale values, but a good agreement for larger scales. The clustering algorithm performs insufficiently for the surface-layer data, but can still be a promising approach for structures on much larger scales.

The time series results agree well with the LES results, apart from a small bias, for the wavelet and cluster analysis. The strong underestimation of length scales can be explained by the insufficient length of the time series to uphold the assumption of ergodicity. For canopy flows it has been suggested to use the advection velocity \(u_\mathrm{a}\), or convection velocity, derived from the time-maximum of the autocorrelation for a given shift in mean wind direction, as the conversion factor from time to spatial scales in Taylor’s hypothesis (Shaw et al. 1995, cf. Table 3). However, this would only increase the integral length scales by a factor \(u_\mathrm{a}/\overline{u}\approx 1.2\) (cf. Table 3), which is insufficient to compensate the underestimation, and it would lead to an overestimation in most other cases.

Lidar overestimation factor of corrected integral length scales (a), wavelet ramp lengths (b) and cluster lengths (c) as a function of the high-resolution integral scales, normalized with the lidar grid resolution. Data points, colours and error bars are as in Fig. 7. For better visibility the axes were truncated, the original error bars reach up to \(\Lambda ^c_\mathrm{LIDAR}/\Lambda ^c_\mathrm{LES}=22\) in (c) and up to \(\Lambda ^r_\mathrm{LES}/\Delta p\) = 18 in (b)

4 Summary

Our goal was to determine whether dual-Doppler lidar measurements can be used to detect and quantify coherent structures in the atmospheric surface layer. To this effect we performed virtual dual-Doppler lidar measurements and retrieval in high-resolution LES surface-layer data and applied three different structure detection techniques to both the virtual lidar and original LES horizontal wind-field data and compared the resulting coherent structure length-scale distributions.

We found that the integral length scales of the lidar data agree particularly well with those of the LES data, provided that the original dual-lidar scales are corrected using additional high-frequency variance measurements. To detect single structures, the wavelet analysis is suitable for large-scale structures. The method fails however as soon as the energetically dominant wavelet scale becomes smaller than the lidar averaging scale, leading to random results and a strong overestimation. The clustering algorithm is unsuitable for surface-layer structures, since here the connected regions of low-speed fluid are much smaller than the lidar averaging scale, the inherent lidar smoothing therefore leads to an uncorrectable overestimation of scales. To summarize, wavelet analysis and especially the clustering algorithm should be reserved for the analysis of structures much larger than the lidar averaging scale when investigating dual-lidar data, the integral length scale can however be successfully determined even for structures on the order of the lidar scale.

The effective dual-lidar averaging scale is not only determined by the pulse width and retrieval grid size, but also due to the scan time duration by the wind-field displacement during the scan intervals. It can therefore assume different values for differing background wind speeds and must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

While the dual-lidar spatial scale analysis generally tends to overestimate structure length scales, tower measurements show a tendency for underestimation of the integral scales, but only a small bias for the wavelet and cluster techniques. The correlation lengths are underestimated mainly due to the time series not fulfilling the ergodic hypothesis, and further conceivable error sources for all three techniques are a breakdown of Taylor’s hypothesis with time and non-optimal positions of the tower with respect to the structures.

References

Adrian RJ (2007) Hairpin vortex organization in wall turbulence. Phys Fluids 19(4):041301

Adrian RJ, Liu ZC (2002) Observation of vortex packets in direct numerical simulation of fully turbulent channel flow. J Vis 5(1):9–19

Adrian RJ, Meinhart CD, Tomkins CD (2000) Vortex organization in the outer region of the turbulent boundary layer. J Fluid Mech 422:1–54

Agee EM (1984) Observations from space and thermal convection: a historical perspective. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 65(9):938–949

Barthlott C, Drobinski P, Fesquet C, Dubos T, Pietras C (2007) Long-term study of coherent structures in the atmospheric surface layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 125(1):1–24

Collineau S, Brunet Y (1993a) Detection of turbulent coherent motions in a forest canopy, part I: wavelet analysis. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 65(4):357–379

Collineau S, Brunet Y (1993b) Detection of turbulent coherent motions in a forest canopy, part II: time-scales and conditional averages. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 66(1–2):49–73

Deardorff JW, Willis GE, Stockton BH (1980) Laboratory studies of the entrainment zone of a convectively mixed layer. J Fluid Mech 100(1):41–64

Etling D, Brown RA (1993) Roll vortices in the planetary boundary layer: a review. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 65(3):215–248

Feingold G, Koren I, Wang H, Xue H, Brewer WA (2010) Precipitation-generated oscillations in open cellular cloud fields. Nature 466(7308):849–852

Frehlich R (1997) Effects of wind turbulence on coherent Doppler lidar performance. J Atmos Ocean Technol 14(1):54–75

Frehlich R (2001) Errors for space-based Doppler lidar wind measurements: definition, performance, and verification. J Atmos Ocean Technol 18(11):1749–1772

Frehlich R, Hannon SM, Henderson SW (1998) Coherent Doppler lidar measurements of wind field statistics. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 86(2):233–256

Hartmann J, Kottmeier C, Raasch S (1997) Roll vortices and boundary-layer development during a cold air outbreak. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 84(1):45–65

Hellsten A, Zilitinkevich S (2013) Role of convective structures and background turbulence in the dry convective boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 149(3):323–353

Hommema S, Adrian R (2003) Packet structure of surface eddies in the atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 106(1):147–170

Inagaki A, Kanda M (2010) Organized structure of active turbulence over an array of cubes within the logarithmic layer of atmospheric flow. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 135(2):209–228

Iwai H, Ishii S, Tsunematsu N, Mizutani K, Murayama Y, Itabe T, Yamada I, Matayoshi N, Matsushima D, Weiming S, Yamazaki T, Iwasaki T (2008) Dual-Doppler lidar observation of horizontal convective rolls and near-surface streaks. Geophys Res Lett 35(14):L14808

Khanna S, Brasseur JG (1998) Three-dimensional buoyancy- and shear-induced local structure of the atmospheric boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 55(5):710–743

Kim S, Park S (2003) Coherent structures near the surface in a strongly sheared convective boundary layer generated by large-eddy simulation. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 106(1):35–60

Lenschow DH, Stankov BB (1986) Length scales in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 43(12):1198–1209

Lenschow DH, Mann J, Kristensen L (1994) How long is long enough when measuring fluxes and other turbulence statistics? J Atmos Ocean Technol 11(3):661–673

Lin C-L, McWilliams JC, Moeng C-H, Sullivan PP (1996) Coherent structures and dynamics in a neutrally stratified planetary boundary layer flow. Phys. Fluids 8(10):2626–2639

Louis AK, Maaß P, Rieder A (1998) Wavelets: Theorie und Anwendungen, Teubner-Studienbücher: Mathematik, 2nd edn. Teubner, Stuttgart, 342 pp

Moeng C-H, Sullivan PP (1994) A comparison of shear- and buoyancy-driven planetary boundary layer flows. J Atmos Sci 51(7):999–1022

Newsom R, Calhoun R, Ligon D, Allwine J (2008) Linearly organized turbulence structures observed over a suburban area by dual-Doppler lidar. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 127(1):111–130

Raasch S, Etling D (1991) Numerical simulation of rotating turbulent thermal convection. Beitr Phys Atmos 64(3):185–199

Raasch S, Schröter M (2001) PALM—a large-eddy simulation model performing on massively parallel computers. Meteorol Z 10(5):363–372

Robinson SK (1991) Coherent motions in the turbulent boundary layer. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 23(1):601–639

Röhner L, Träumner K (2013) Aspects of convective boundary layer turbulence measured by a dual-Doppler lidar system. J Atmos Ocean Technol 30(9):2132–2142

Segalini A, Alfredsson PH (2012) Techniques for the eduction of coherent structures from flow measurements in the atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 143(3):433–450

Shannon C (1949) Communication in the presence of noise. Proc IRE 37(1):10–21

Shaw R, Brunet Y, Finnigan J, Raupach M (1995) A wind tunnel study of air flow in waving wheat: two-point velocity statistics. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 76(4):349–376

Stawiarski C, Träumner K, Knigge C, Calhoun R (2013) Scopes and challenges of dual-Doppler lidar wind measurements—an error analysis. J Atmos Ocean Technol 30(9):2044–2062

Stull RB (1988) An introduction to boundary layer meteorology. Atmospheric and Oceanographic Sciences Library. Kluwer, Dordrecht 666 pp

Tennekes H, Lumley JL (1972) A first course in turbulence. The MIT Press. Cambridge, 300 pp

Thomas C, Foken T (2005) Detection of long-term coherent exchange over spruce forest using wavelet analysis. Theor Appl Climatol 80(2–4):91–104

Thomas C, Foken T (2007) Flux contribution of coherent structures and its implications for the exchange of energy and matter in a tall spruce canopy. Boundary-Layer Metetorol 123(2):317–337

Thomas CK, Kennedy AM, Selker JS, Moretti A, Schroth MH, Smoot AR, Tufillaro NB, Zeeman MJ (2012) High-resolution fibre-optic temperature sensing: a new tool to study the two-dimensional structure of atmospheric surface-layer flow. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 142(2):177–192

Träumner K, Damian T, Stawiarski C, Wieser A (2014) Turbulent structures and coherence in the atmospheric surface layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 154:1–25

Willis G, Deardorff J (1976) On the use of Taylor’s translation hypothesis for diffusion in the mixed layer. Q J R Meteorol Soc 102(434):817–822

Wyngaard JC (2010) Turbulence in the atmosphere. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 406 pp

Young GS, Kristovich DAR, Hjelmfelt MR, Foster RC (2002) Rolls, streets, waves, and more—a review of quasi-two-dimensional structures in the atmospheric boundary layer. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 83(7):997–1001

Zeeman MJ, Eugster W, Thomas CK (2013) Concurrency of coherent structures and conditionally sampled daytime sub-canopy respiration. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 146(1):1–15

Zhang Y, Liu H, Foken T, Williams QL, Mauder M, Thomas C (2011) Coherent structures and flux contribution over an inhomogeneously irrigated cotton field. Theor Appl Climatol 103(1–2):119–131

Zhou J, Adrian RJ, Balachandar S, Kendall TM (1999) Mechanisms for generating coherent packets of hairpin vortices in channel flow. J Fluid Mech 387:353–396

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for many valuable comments and suggestions. This project was part of a PhD thesis at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and received financial support by the ‘Concept for the Future’ of KIT within the framework of the German Excellence Initiative. It was also partly supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant RA 617/19-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Stawiarski, C., Träumner, K., Kottmeier, C. et al. Assessment of Surface-Layer Coherent Structure Detection in Dual-Doppler Lidar Data Based on Virtual Measurements. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 156, 371–393 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0039-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0039-3