Abstract

Preserving species within protected areas (PAs) does not guarantee adequate levels of protection if not coupled with conservation of functional connectivity for a target species. We propose an analytical framework to assess the effectiveness of PAs in preserving habitat and functional connectivity for mobile vertebrates. We implemented it in central Italy by using as a case study a bat species (common noctule, Nyctalus noctula) to: (i) determine suitable areas by means of Species Distribution Models (SDMs); (ii) identify potential commuting corridors through a functional connectivity analysis; (iii) develop a new tool to rank corridors according to their functional irreplaceability; (iv) implement a gap analysis on both suitable areas and functional corridors; and (v) propose management recommendations for the conservation of N. noctula. The SDM output and a set of proxies of commuting routes were used to build a resistance layer for the connectivity analysis. The resulting functional corridors were ranked according to their isolation (distance to other corridors and to suitable areas) to obtain an irreplaceability index, with isolated corridors scoring high values. The PA effectiveness assessed by overlapping the PA map with the SDM and the ranked functional corridors highlighted that PAs cover just a small portion of suitable sites (20.3%) and functional corridors for the species (20.8%). The irreplaceability index allowed us to identify those areas inside and outside the PAs that critical for persistence of the species in question require immediate protection regimes. The approach we present could be easily extended to other taxa and offers sound insight on how to promote the conservation at landscape scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abell R, Allan JD, Lehner B (2007) Unlocking the potential of protected areas for freshwaters. Biol Conserv 134(1):48–63

Ana SL, Rodrigues H, Akçakaya R, Andelman SJ, Bakarr MI, Boitani L, Brooks TM, Chanson JS, Fishpool LDC, Da Fonseca GAB, Gaston KJ, Hoffmann M, Marquet PA, Pilgrim JD, Pressey RL, Schipper J, Sechrest W, Stuart SN, Underhill LG, Waller RW, Watts MEJ, Yan X (2004) Global gap analysis: priority regions for expanding the global protected-area network. Bioscience 54(12):1092–1100

Bellamy C, Altringham J (2015) Predicting species distributions using record centre data: multi-scale modelling of habitat suitability for bat roosts. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0128440

Bodin O, Saura S (2010) Ranking individual habitat patches as connectivity providers: integrating network analysis and patch removal experiments. Ecol Mod 221:2393–2405

Bosso L, Rebelo H, Garonna AP, Russo D (2013) Modelling geographic distribution and detecting conservation gaps in Italy for the threatened beetle Rosalia alpina. J Nat Conserv 21(2):72–80

Bosso L, Di Febbraro M, Cristinzio G, Zoina A, Russo D (2016) Shedding light on the effects of climate change on the potential distribution of Xylella fastidiosa in the Mediterranean basin. Biol Invasions 18(6):1759–1768

Boughey KL, Lake IR, Haysom KA, Dolman PM (2011) Improving the biodiversity benefits of hedgerows: how physical characteristics and the proximity of foraging habitat affect the use of linear features by bats. Biol Conserv 144(6):1790–1798

Butterfield BR, Csuti B, Scott JM (1994) Modeling vertebrate distributions for gap analysis. In: Miller RI (ed) Mapping the diversity of nature. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 53–68

Camprodon and Guixé (2013) Population status, roost selection and spatial ecolgoy of the Greater noctule bat (Nyctalus lasiopterus) and the common noctule (Nyctalus noctula) in Catalonia. Barbastella 6(1):51–59

Caracciolo F, Lombardi P (2012) A new-institutional framework to explore the trade-off between agriculture, environment and landscape. Econ Policy of Energy Environ 3:135–154

Carranza ML, Frate L, Paura B (2012a) Structure, ecology and plant richness patterns in fragmented beech forests. Plant Ecol Divers 5(4):541–551

Carranza ML, D’Alessandro E, Saura S, Loy A (2012b) Assessing habitat connectivity for semi- aquatic vertebrates The case of the endangered otter in Italy. Landsc Ecol. 27(2):281–290

Chambers JM, Cleveland WS, Kleiner B, Tukey PA (1983) Graphical methods for data analysis. Wadsworth and Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove

Chen Y, Zhang J, Jiang J, Nielsen SE, He F (2017) Assessing the effectiveness of China’s protected areas to conserve current and future amphibian diversity. Divers Distrib 23(2):146–157

Cianfrani C, Maiorano L, Loy A, Kranz A, Lehmann A, Maggini R, Guisan A (2013) There and back again? Combining habitat suitability modelling and connectivity analyses to assess a potential return of the otter to Switzerland. Anim Conserv 16(5):584–594

Compton BW, McGarigal K, Cushman SA, Gamble LR (2007) A resistant-kernel model of connectivity for amphibians that breed in vernal pools. Conserv Biol 21(3):788–799

Cowen RK, Paris CB, Srinivasan A (2006) Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Science 311(5760):522–527. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122039

Crooks KR, Sanjayan M (eds) (2006) Connectivity conservation, vol 14. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cushman SA, McKelvey KS, Hayden J, Schwartz MK (2006) Gene flow in complex landscapes: testing multiple hypotheses with causal modeling. Am Nat 168(4):486–499

Cushman SA, McKelvey KS, Schwartz MK (2009) Use of empirically derived source-destination models to map regional conservation corridors. Conserv Biol 23(2):368–376

Cushman SA, Lewis JS, Landguth EL (2013) Evaluating the intersection of a regional wildlife connectivity network with highways. Mov Ecol 1(1):12

DeFries R, Hansen A, Newton AC, Hansen MC (2005) Increasing isolation of protected areas in tropical forests over the past twenty years. Ecol Appl 15(1):19–26

DeFries R, Hansen A, Turner BL, Reid R, Liu J (2007) Land use change around protected areas: management to balance human needs and ecological function. Ecol Appl 17(4):1031–1038

Déjeant-Pons M (2006) The European landscape convention. Landsc Res 31(4):363–384

Di Febbraro M, Roscioni F, Frate L, Carranza ML, De Lisio L, De Rosa D, Marchetti M, Loy A (2015) Long term effect of traditional and conservation-oriented forest management on the distribution of vertebrates in Mediterranean forests: a hierarchichal hybrid modelling approach. Divers Distrib 21(10):1141–1154

Ducci L, Agnelli P, Di Febbraro M, Frate L, Russo D, Loy A, Carranza ML, Santini G, Roscioni F (2015) Different bat guilds perceive their habitat in different ways: a multiscale landscape approach for variable selection in species distribution modelling. Landsc Ecol 30(10):2147–2159

Ehrenbold AF, Bontadina F, Arlettaz F, Obrist MK (2013) Landscape connectivity, habitat structure and activity of bat guilds in farmland-dominated matrices. J Appl Ecol 50(1):252–261

Elith J, Graham CH, Person RP, Dudík M, Ferrier S, Guisan A, Hijmans RJ, Huettmann F, Leathwick JR, Lehmann A, Li J, Lohmann LG, Loiselle BA, Manion G, Moritz C, Nakamura M, Nakazawa Y, Mc. Overton J, Peterson AT, Phillips SJ, Karen Richardson K, Scachetti-Pereira RR, Schapire RE, Soberón J, Williams S, Wisz MS, Zimmermann NE (2006) Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129–151

Estrada A, Real R, Vargas JM (2008) Using crisp and fuzzy modelling to identify favourability hotspots useful to perform gap analysis. Biodivers Conserv 17(4):857–871

Europe C. O. (2000). European landscape convention. In: Report and convention

Fahrig L, Pedlar JH, Pope SE, Taylor PD, Wegner JF (1995) Effect of road traffic on amphibian density. Biol Conserv 73(3):177–182

Ficetola GF, Thuiller W, Padoa-Schioppa E (2009) From introduction to the establishment of alien species: bioclimatic differences between presence and reproduction localities in the slider turtle. Divers Distrib 15(1):108–116

Ficetola GF, Maiorano L, Falcucci A, Dendoncker N, Boitani L, Padoa-Schioppa E, Miaud C, Thuiller W (2010) Knowing the past to predict the future: land-use change and the distribution of invasive bullfrogs. Glob Change Biol 16(2):528–537

Foresta M, Carranza ML, Garfì V, Di Febbraro M, Marchetti M, Loy A (2016) A systematic conservation planning approach to fire risk management in Natura 2000 sites. J Environ Manag 181:574–581

Foster D, Swanson F, Aber J, Burke I, Brokaw N, Tilman D, Knapp A (2003) The importance of land-use legacies to ecology and conservation. Bioscience 53(1):77–88

Frate L, Acosta ATR, Cabido M, Hoyos L, Carranza ML (2015) Temporal changes in forest fragmentation contexts at multiple extents: patch, perforated, edge and interior forests in the Gran Chaco, Central Argentina. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142855

Geldmann J, Coad L, Barnes M, Craigie ID, Hockings M, Knights K, Leverington F, Cuadros IC, Zamora C, Woodley S, Burgess ND (2015) Changes in protected area management effectiveness over time: a global analysis. Biol Conserv 191:692–699

Geri F, Amici V, Rocchini D (2010) Human activity impact on the heterogeneity of a Mediterranean landscape. Appl Geogr 30(3):370–379

Guisan A, Thuiller W (2005) Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol Lett 8:993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00792.x

Hale JD, Fairbrass AJ, Matthews TJ, Sadler JP (2012) Habitat composition and connectivity predicts bat presence and activity at foraging sites in a large UK conurbation. PLoS ONE 7(3):e33300

Hein CD, Castleberry SB, Miller KV (2009) Site-occupancy of bats in relation to forested corridors. For Ecol Manag 257(4):1200–1207

Hirzel AH, Le Lay G, Helfer V, Randin C, Guisan A (2006) Evaluating the ability of habitat suitability models to predict species presences. Ecol Model 199(2):142–152

Jantke K, Schleupner C, Schneider UA (2011) Gap analysis of European wetland species: priority regions for expanding the Natura 2000 network. Biodivers Conserv 20(3):581–605

Kelm DH, Lenski J, Kelm V, Toelch U, Dziock F (2014) Seasonal bat activity in relation to distance to hedgerows in an agricultural landscape in central Europe and implications for wind energy development. Acta Chiropterol 16(1):65–73

Kerth G, Melber M (2009) Species-specific barrier effects of a motorway on the habitat use of two threatened forest-living bat species. Biol Conserv 142(2):270–279

Kukkala AS, Arponen A, Maiorano L, Moilanen A, Thuiller W, Toivonen T, Zupan L, Brotons L, Cabeza M (2016) Matches and mismatches between national and EU-wide priorities: examining the Natura (2000) network in vertebrate species conservation. Biol Conserv 198:193–201

Landguth EL, Hand BK, Glassy J, Cushman SA, Sawaya MA (2012) UNICOR: a species connectivity and corridor network simulator. Ecography 35(1):9–14

Le Saout S, Hoffmann M, Hughes A, Bernard C, Brooks TM, Bertzky B, Butchart SNT, Badman T, Rodrigues ASL (2013) Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science 342(6160):803–805. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239268

Lesinski G, Fuszara E, Kowalski M (2000) Foraging areas and relative density of bats (Chiroptera) in differently human transformed landscapes. Mamm Biol 65(3):129–137

Lisón F, Sánchez-Fernández D (2017) Low effectiveness of the Natura 2000 network in preventing land-use change in bat hotspots. Biodivers Conserv 26:1989–2006

Lisón F, Sánchez-Fernández D, Calvo JF (2015) Are species listed in the Annex II of the Habitats Directive better represented in Natura 2000 network than the remaining species? A test using Spanish bats. Biodivers Conserv 24:2459–2473

Lisón F, Altamirano A, Field R, Jones G (2017) Conservation on the blink: deficient technical reports threaten conservation in the Natura 2000 network. Biol Conserv 209:11–16

Lockwood M (2010) Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: a framework, principles and performance outcomes. J Environm Manage 91(3):754–766

Luque S, Saura S, Fortin MJ (2012) Landscape connectivity analysis for conservation: insights from combining new methods with ecological and genetic data. Landsc Ecol 27(2):153–157

Mackie IJ, Racey PA (2007) Habitat use varies with reproductive state in noctule bats (Nyctalus noctula): implications for conservation. Biol Conserv 140(1):70–77

Maiorano L, Falcucci A, Boitani L (2006) Gap analysis of terrestrial vertebrates in Italy: priorities for conservation planning in a human dominated landscape. Biol Conserv 133(4):455–473

Maiorano L, Falcucci A, Garton EO, Boitani L (2007) Contribution of the Natura 2000 network to biodiversity conservation in Italy. Conserv Biol 21(6):1433–1444

Margules CR, Pressey RL (2000) Systematic conservation planning. Nature 405:243–253

Mazaris AD, PapanikolaouAD Barbet-Massin M, Kallimanis AS, Jiguet F, Schmeller DS, Pantis JD (2013) Evaluating the connectivity of a protected areas’ network under the prism of global change: the efficiency of the European Natura 2000 Network for four birds of prey. PLoS ONE 8(3):e59640

McGarigal K, Cushman SA (2005) The gradient concept of landscape structure. In: Wiens JA, Moss MR (eds) Issues and perspectives in landscape ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 112–119

Medina A, Harvey CA, Merlo DS, Vílchez S, Hernández B (2007) Bat diversity and movement in an agricultural landscape in Matiguás, Nicaragua. Biotropica 39(1):120–128

Morris AD, Miller DA, Kalcounis-Rueppell MC (2010) Use of forest edges by bats in a managed pine forest landscape. J Wildl Manage 74(1):26–34

Muscarella R, Galante PJ, Soley-Guardia M, Boria RA, Kass JM, Uriarte M, Anderson RP (2014) ENMeval: an R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for Maxent ecological niche models. Methods Ecol Evol 5(11):1198–1205

Oliveira U, Soares-Filho BS, Paglia AP, Brescovit AD, Carvalho CJ, Silva DP, Stehmann JR (2017) Biodiversity conservation gaps in the Brazilian protected areas. Sci Rep 7(1):9141

Phillips SJ, Dudík M (2008) Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31(2):161–175

Phillips SJ, Dudík M, Schapire RE (2004) A maximum entropy approach to species distribution modeling. In: Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning (p. 83). ACM

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Model 190(3):231–259

Razgour O, Rebelo H, Puechmaille SJ, Juste J, Ibáñez C, Kiefer A, Burke T, Dawson DA, Jones G (2014) Scale-dependent effects of landscape variables on gene flow and population structure in bats. Divers Distrib 20(10):1173–1185

Rebelo H, Jones G (2010) Ground validation of presence-only modelling with rare species: a case study on barbastelles Barbastella barbastellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). J Appl Ecol 47:410–420

Riitters KH, Wickham JD, O’Neill R, Jones KB, Smith ER, Coulston JW et al (2002) Fragmentation of continental United States forests. Ecosystems 5:815–822

Rodrigues AS, Andelman SJ, Bakarr MI, Boitani L, Brooks TM, Cowling RM, Yan X (2004) Effectiveness of the global protected area network in representing species diversity. Nature 428(6983):640–643

Roeleke M et al (2016) Habitat use of bats in relation to wind turbines revealed by GPS tracking. Sci Rep 6:28961. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28961

Rogers DS, Belk MC, González MW, Coleman BL (2006) Patterns of habitat use by bats along a riparian corridor in northern Utah. Southwest Nat 51(1):52–58

Rosati L, Marignani M, Blasi C (2008) A gap analysis comparing Natura 2000 vs national protected area network with potential natural vegetation. Community Ecol 9(2):147–154

Roscioni F, Russo D, Di Febbraro M, Frate L, Carranza ML, Loy A (2013) Regional-scale modelling of the cumulative impact of wind farms on bats. Biodivers Conserv 22(8):1821–1835

Roscioni F, Rebelo H, Russo D, Carranza ML, Di Febbraro M, Loy A (2014) A modelling approach to infer the effects of wind farms on landscape connectivity for bats. Landsc Ecol 29(5):891–903

Ruczyński I, Kalko EK, Siemers BM (2007) The sensory basis of roost finding in a forest bat Nyctalus noctula. J Exp Biol 210(20):3607–3615

Ruczyński I, Nichols B, Mac Leon CD, Racey PA (2010) Selection of roosting habitats by Nyctalus noctula and Nyctalus leisleri in Białowieża Forest—adaptive response to forest management? Forest Ecol Manage 259:1633–1641

Russo D, Jones G (2002) Identification of twenty-two bat species (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from Italy by analysis of time-expanded recordings of echolocation calls. J Zool 258(01):91–103

Russo D, Jones G (2003) Use of foraging habitats by bats in a Mediterranean area determined by acoustic surveys: conservation implications. Ecography 26(2):197–209

Russo D, Jones G, Migliozzi A (2002) Habitat selection by the Mediterranean horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus euryale (Chiroptera: rhinolophidae) in a rural area of southern Italy and implications for conservation. Biol Conserv 107(1):71–81

Saura S, Pascual-Hortal L (2007) A new habitat availability index to integrate connectivity in landscape conservation planning: comparison with existing indices and application to a case study. Landsc Urb Plan 83(2):91–103

Saura S, Torne J (2009) Conefor Sensinode 2.2: a software package for quantifying the importance of habitat patches for landscape connectivity. Environm Model Soft 24(1):135–139

Saura S, Estreguil C, Mouton C, Rodríguez-Freire M (2011) Network analysis to assess landscape connectivity trends: application to European forests (1990–2000). Ecol Indic 11(2):407–416

Saura S, Bodin Ö, Fortin MJ (2014) Stepping stones are crucial for species’ long-distance dispersal and range expansion through habitat networks. J Appl Ecol 51(1):171–182

Sawyer SC, Epps CW, Brashares JS (2011) Placing linkages among fragmented habitats: do least-cost models reflect how animals use landscapes? J Appl Ecol 48(3):668–678

Scott SJ, McLaren G, Jones G, Harris S (2010) The impact of riparian habitat quality on the foraging and activity of pipistrelle bats (Pipistrellus spp.). J Zool 280(4):371–378

Smeraldo S, Di Febbraro M, Ćirović D, Bosso L, Trbojević I, Russo D (2017) Species distribution models as a tool to predict range expansion after reintroduction: a case study on Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber). J Nat Conserv 37:12–20

Sork VL, Smouse PE (2006) Genetic analysis of landscape connectivity in tree populations. Lands Ecol 21(6):821–836

Vandevelde JC, Bouhours A, Julien JF, Couvet D, Kerbiriou C (2014) Activity of European common bats along railway verges. Ecol Engin 64:49–56

Wasserman TN, Cushman SA, Littell, JS, Shirk AJ, Landguth, EL (2012) Multi scale habitat relationships of Martes americana in northern Idaho, U.S.A. Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-94. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, p 21

Waters D, Jones G, Furlong M (1999) Foraging ecology of Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri) at two sites in southern Britain. J Zool 249(02):173–180

Wilcoxon F (1945) Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics bull 1(6):80–83

Zehetmair T, Müller J, Runkel V, Stahlschmidt P, Winter S, Zharov A, Gruppe A (2014) Poor effectiveness of Natura 2000 beech forests in protecting forest-dwelling bats. J Nat Conserv 23:53–60

Zeller KA, McGarigal K, Whiteley AR (2012) Estimating landscape resistance to movement: a review. Landsc Ecol 27(6):777–797

Zukal J, Rehák Z (2006) Flight activity and habitat preference of bats in a karstic area, as revealed by bat detectors. Folia Zool 55(3):273

Acknowledgements

We thank NEMO s.r.l. for providing the maps of protected areas. Thanks also go to Erin Landguth for her support in the UNICOR procedures.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by David Hawksworth.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Environmental variables and maps used for modelling the distribution of N. Noctula in the Tuscany region: (a) environmental variables, (b) reclassification scheme for Corine Land Cover, (c) reclassified Corine Land Cover map.

(a) Environmental variables used in the Species Distribution Model for N. Noctula. DEM: Digital Elevation Model. CLC: Corine Land Cover.

Variables | Code | Source of maps and scale |

|---|---|---|

Elevation (m) | DEM | DEM: cell size 100 m Year 2005 MATTM Geoportale Nazionale |

Hidrography | Hydro | Hydrographic map: scale: 1:100.000 Year 2008 MATTM-Geoportale Nazionale |

Cover types | ReclCLC | Corine Land Cover map: scale: 1:100.000 year 2006 EEA CLC expanded to a IV level of detail developed for Italy (MATTM- Geoportale Nazionale) |

(b) Reclassification scheme for Corine Land Cover.

CLC original codes | CLC names | New classes | New names |

|---|---|---|---|

1.1.1 | Continuous urban fabric | 100 | Urban |

1.1.2 | Discontinuous urban fabric | 100 | Urban |

1.2.1 | Industrial or commercial unit | 100 | Urban |

1.2.2 | Road and rail networks and associated land | 100 | Urban |

1.2.3 | Port areas | 100 | Urban |

1.2.4 | Airports | 100 | Urban |

1.3.1 | Mineral extraction sites | 131 | Mineral extraction sites |

1.3.2 | Dump sites | 100 | Urban |

1.3.3 | Construction sites | 100 | Urban |

1.4.1 | Green urban areas | 100 | Urban |

1.4.2 | Sport and leisure facilities | 100 | Urban |

2.1.1. | Non-irrigated arable land | 210 | Cultivation |

2.1.3 | Rice fields | 210 | Cultivation |

2.2.1 | Vineyards | 220 | Orchard |

2.2.2 | Fruit trees and berry plantation | 220 | Orchard |

2.2.3 | Olive groves | 220 | Orchard |

2.3.1 | Pastures | 230 | Pastures |

2.4.1 | Annual crops associated with permanent crops | 240 | Heterogeneous agricultural areas |

2.4.2 | Complex cultivation pattern | 240 | Heterogeneous agricultural areas |

2.4.3 | Land principally occupied by agriculture, with significant areas of natural vegetation | 240 | Heterogeneous agricultural areas |

2.4.4 | Agro-forestry area | 240 | Heterogeneous agricultural areas |

3.1.1 | Broad-leaved forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.1 | Holm-oak and cork-oak forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.2 | Decidous oak forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.3 | Mesophillous broad-leaved forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.4 | Chestnut forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.5 | Beech forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.1.6 | Igrophyllous forests | 3.1.1.6 | Riparian forests |

3.1.1.7 | Exotic broad-leaved forests | 310 | Forests |

3.1.2 | Coniferous forests | 312 | Coniferous |

3.1.2.1 | Mediterranean pine forests | 312 | Coniferous |

3.1.2.2 | Mountain and oromediterranean pine forests | 312 | Coniferous |

3.1.2.3 | Spruce forests | 312 | Coniferous |

3.1.2.5 | Exotic coniferous forests | 312 | Coniferous |

3.1.3 | Mixed forests | Mixed forests | |

3.1.3.1 | Broad lived dominated forests | 313 | Mixed forests |

3.1.3.2 | Coniferous dominated forests | 313 | Mixed forests |

3.2.1 | Natural grassland | 321 | Steppe |

3.2.1.1. | Continuous grassland | 321 | Steppe |

3.2.1.2 | Discontinuous grassland | 321 | Steppe |

3.2.3 | Sclerophyllous vegetation | 323 | Scrubs |

3.2.3.1 | Tall maquis | 323 | Scrubs |

3.2.3.2 | Low maquis and garrigue | 323 | Scrubs |

3.2.4 | Transitional woodland-shrub | 323 | Scrubs |

3.3.1 | Beaches dune and sands | 330 | Bare ground |

3.3.2 | Bare rocks | 330 | Bare ground |

3.3.3 | Sparsely vegetated area | 330 | Bare ground |

4.1.1 | Inland marshes | 410 | Water |

4.2.1 | Salt marshes | 510 | Salt Water |

4.2.2 | Salines | 510 | Salt Water |

5.1.1 | Water courses | 410 | Water |

5.1.2 | Water bodies | 410 | Water |

5.2.1 | Coastal lagoons | 510 | Salt Water |

(c) Reclassified Corine Land Cover map of Tuscany region (ReclCLC).

Appendix 2

Resistance surface for N. noctula in Tuscany region (Central Italy). Low resistance refers to the suitable areas for the species, medium resistance to areas that being external to suitable habitats contain elements that allow bat movement as high slopes, forest edges and watercourses. High resistance indicates unsuitable areas with no connecting elements for the species.

Appendix 3

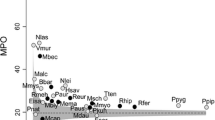

Variables importance and response curves for Nyctalus noctula in Tuscany region (central Italy) as identified by MaxEnt analysis. (a) Jacknife of regularized training gain to highlight the variable importance; (b) Response curves.

The environmental variable with the highest gain is ReclCLC, which therefore appears to have the most useful information by itself. In fact this variable is also the one that decreases most the gain when it is omitted.

Response curve of Nyctalus noctula to DEM. The curve shows the mean response of the 50 replicate Maxent runs (red) and the mean standard deviation (blue).

Response curve of Nyctalus noctula to Hydro. The curve shows the mean response of the 50 replicate Maxent runs (red) and the mean standard deviation (blue).

Response of Nyctalus noctula to ReclCLC. The response of this variable is expressed by a bar plot as it is categorical. CLC codes: 100—urban; 131—mineral extraction sites; 210—cultivation; 220—orchards; 230—pastures; 240—heterogeneous agricultural areas; 310—broad leaved forests; 3116—riparian forests; 312—coniferous; 313—mixed forests; 321—steppe; 323—scrubs; 330—bare ground; 410—water; 510—salt water.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ducci, L., Roscioni, F., Carranza, M.L. et al. The role of protected areas in preserving habitat and functional connectivity for mobile flying vertebrates: the common noctule bat (Nyctalus noctula) in Tuscany (Italy) as a case study. Biodivers Conserv 28, 1569–1592 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01744-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01744-5