Abstract

Despite significant progress in understanding climate risks, adaptation efforts in biodiversity conservation remain limited. Adaptation requires addressing immediate conservation threats while also attending to long term, highly uncertain and potentially transformative future changes. To date, conservation research has focused more on projecting climate impacts and identifying possible strategies, rather than understanding how governance enables or constrains adaptation actions. We outline an approach to future-oriented conservation that combines the capacities to anticipate future ecological change; to understand the implications of that change for social, political and ecological values; and the ability to engage with the governance (and politics) of adaptation. Our approach builds on the adaptive management and governance literature, however we explicitly address the (often contested) rules, knowledge and values that enable or constrain adaptation. We call for a broader focus that extends beyond technical approaches to acknowledge the socio-political challenges inherent to adaptation. More importantly, we suggest that conservation policy makers and practitioners can use this approach to facilitate learning and adaptation in the context of complexity, transformational change and uncertainty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global environmental change is creating wide-ranging impacts on biodiversity and people. While the details are highly uncertainty, transformational change seems increasingly likely. Yet much conservation practice remains static, seeking to maintain ecosystems and species in a pre-disturbance condition by focusing on containing immediate threats like poaching and habitat conversion (Leverington et al. 2010). Adaptive management and adaptive governance have been proposed as learning-based approaches that will enable conservation to address uncertainty and complexity (Folke et al. 2005; Armitage et al. 2011). While these approaches can inform climate adaptation, implementation presents an ongoing challenge (Holley et al. 2012; Schultz et al. 2015; Wyborn and Dovers 2014).

The scope, magnitude and uncertainty associated with projections of climatic and ecological change necessitate a critical assessment of conservation goals—which are ultimately determined by societal values and political processes (Heller and Hobbes 2014; Dunlop et al. 2013; Stein et al. 2013). Whose knowledge counts in setting these goals? Which values are to be conserved? What processes are used to design and implement new goals? These questions require deeper engagement with the governance of adaptation—the rules, policies and values that shape how different stakeholders engage with adaptation (Wyborn et al. 2014). Governance influences how we respond to new knowledge and uncertainty about climate impacts, how adaptation is framed and ultimately what is implemented.

This paper is situated within a growing body of research that conceptualizes adaptation as a process mediated by social and political relations (Erikson et al. 2015; Pelling 2011; Obrien and Selboe 2015). We build on the social-ecological systems framing and learning approach of adaptive governance (Cosens et al. 2014), and in particular the emphasis on integrating scientific and other types of knowledge into governance and management (Armitage et al. 2011). However, we are particularly interested in the intersection of knowledge and governance (after Ericksen et al. 2015; Wyborn 2015; van Kerkhoff 2013; Leach et al. 2010), as this provides insights into whether and how knowledge about future climate impacts is likely to be incorporated into existing decision-making processes.

Conservation, by its definition is focused on conserving places as relics of the past. To remain relevant, and to mediate the implications of global environmental change, we propose that conservation policy and practice must develop approaches that look to the future. A ‘future oriented’ approach can build on adaptive management and governance, but also needs to develop the knowledge and capacities required to conceptualize future change; to consider social, political and ecological values at stake in large-scale system transformations, and to understand the implications for practical conservation interventions including goals, strategies and measures of success.

Background

Over the past decade, the conservation community has directed significant investment into understanding climate impacts on biodiversity (Willis and Bhagwat 2009; Watson et al. 2013; Pacifici et al. 2015). This has led to a proliferation of tools, strategies and guidelines, predominantly targeting species, site or sub-regional scales. These include planning tools (e.g., Cross et al. 2012; Glick et al. 2011), modeling approaches (Pacific et al. 2015), management strategies (e.g. increasing connectivity, translocation; Mawdsley 2011; Groves et al. 2012), planning principles (Watson et al. 2011) and overarching approaches [e.g., ecosystem-based adaptation, community-based adaptation, adaptive governance see Reid (2015); Armitage et al. (2011)].

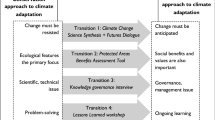

Impact and vulnerability assessments often focus on the magnitude of environmental change, the sensitivity of a species or ecosystem to change, and their likely resilience to these changes. In addition to their role in providing insight into projected change, these assessments are generally conceived as the first step in adaptation planning. Most adaptation assessments follow a broadly standardized series of steps (see Fig. 1, Glick et al. 2011).

Standardized approach to planning and implementing adaptation (from Glick et al. 2011)

This learning cycle embodies a rational, evidence-based approach that assumes adequate knowledge can be developed, the social values underpinning prioritization remain stable and consensual, and the rules governing decision-making are likewise stable and effective (Leach et al. 2010). Karpouzoglou et al. (2016) describe this as an ‘aspirational’ approach to governance, whereby decision-making is an exercise in implementing technical, social or organizational options. Here the profound unpredictability of climate change can only be dealt with by strategies that reduce uncertainty—more research, experimentation, modeling, and so forth.

Adaptive governance and management are often called on to inform climate adaptation (Armitage et al. 2011; Cross et al. 2012), however questions are emerging about their practicality in the context of transformative change. Limitations include an inability to accommodate non-stationary dynamics (Williams and Brown 2014), and whether approaches relying largely on trust can respond adequately to large-scale, intensifying pressures and conflicting interests (Schultz et al. 2015), particularly given the widespread assumption in much adaptive governance literature that there is an agreed upon desired future (Chaffin et al. 2014). Moreover, the ‘epistemologically grey’ areas of adaptive governance: power and politics, inclusion and equity, short term and long term change, relationships between public policy and adaptive governance (Karpozoglou et al. 2016), mirror the challenges that adaptation presents for conservation.

Kujala et al. (2013) suggest that for conservation practitioners wishing to develop strategies to address climate change, uncertainty arises from (1) biophysical processes, (2) human actions that impact climate, (3) ecological consequences of climate change, (4), feedbacks between processes, and (5) the objectives of human decision-makers and other participants. While some elements of the first three uncertainties can be reduced by modeling and assessments, these exercises are costly, time-consuming and imperfect. Moreover, the last two uncertainties arise from non-linear relationships that cannot easily be addressed by modeling or by extrapolating recent experience (Pearson and Dawson 2003; Kujala et al. 2013).

Adaptation research has largely focused on identifying projected impacts of change rather than understanding how decisions are made in the context of uncertainty (Klein and Juhola 2014; Wyborn 2015). Research targeted at identifying key vulnerabilities to climate change is insufficient on its own to enable changes in policy and practice (Maru and Stafford Smith 2014; Seimon et al. 2011). Without appropriate processes to consider stakeholder objectives, these assessments may supply information but not provide a clear pathway for adaptation and thus often do not facilitate action Yuen et al. (2012).

Despite significant attention on how to manage ecosystems and species under climate change, there have been far fewer attempts to assess the capacity of conservation organisations themselves to adapt (Armsworth et al. 2015). Yet the governance and institutional context in which organizations operate are widely acknowledged as critical in enabling effective adaptation (Rowland et al. 2011; Lemiueux et al. 2013; Dovers and Hezri 2010; Moser and Ekstrom 2010). Conservation mangers will need to make decisions that extend beyond their experience and capacity to deal with ecological change (Dunlop et al. 2013; Lemieux and Scott 2011; Hagerman et al. 2010), warranting urgent attention to whether the conservation community has the individual psychological or institutional capacity prepare for transformative change.

The barriers to adaptation are many and diffuse: lack of evidence, resources, political commitment, conflicting mandates and priorities, and a concern that short term priorities require more critical attention than long term change (Moser and Ekstrom 2010). Social and cultural barriers also exist and the uncertainties associated with climate change create confusion and make people reluctant to commit to particular courses of action.

This suggests that the willingness to undertake certain adaptation actions is strongly influenced by social, cultural and political context. Activities and strategies are not readily transferable to other settings, even if they share biophysical or ecological similarities. Thus, attention to the politics of how adaptation takes place is equally as important as understanding social or ecological impacts of climate change (Erikson et al. 2015). There are no ‘cookie cutter’ approaches that apply everywhere. Rather, efforts should focus on facilitating locally mediated dialogue to engage with change rather than seeking universal strategies or design principles (Wyborn 2015). Despite a slow start in natural resource management (Yuen et al. 2012), there is a growing interest in the role of social learning to address the complexity and uncertainty inherent to adaptation (Ensor and Harvey 2015; Erikson et al. 2015; Armitage et al. 2011).

Developing a future-oriented conservation

Conservation managers rarely make adaptation decisions in isolation of other pressures and trade-offs. A future-oriented approach to conservation sees adaptation as part of the dynamics of society rather than a narrowly technical adjustment to biophysical change (after Erikson et al. 2015). We propose that when there is a reasonable prospect of ecological change with significant social implications, but there is profound uncertainty about the details of that change, it is useful to reframe adaptation from efforts primarily aimed at reducing biophysical uncertainty, to governance arrangements that will enable adaptation. This requires social and political cultures that value knowledge, but are also ready to take action in the face of uncertainty, adapting as necessary as data and experience build over time.

A future-oriented approach begins with a sound understanding of available information, existing governance contexts and commitments, the range of factors that influence decision-making and the relationships between research, policy and practice. This “decision context” of adaptation has been characterized as the set of values, rules and knowledge that shape whether and how adaptation is implemented in a specific context (Goddard et al. 2016).

Here values represent the personal, cultural and ethical factors that lead to the preferences that people express when confronted with certain knowledge and rules. Rules, or institutions, represent legislation, regulations, constitutions, guidelines, and other formal factors; also societal and personal norms and behaviours. Knowledge refers to the evidence, beliefs and judgments about how the social-ecological system works, an understanding of future changes and the consequences of different decisions.

Where values, knowledge and rules are consistent, the prevailing evidence-based learning works to support decision-making. However, for novel adaptation problems—such as translocation of species, invading native species, sea level rise, major changes to hydrological regimes—there may not be many effective options consistent with prevailing values, rules and knowledge. Adaptation challenges are complicated because in any given situation there will be multiple, often contested, values, rules and knowledge at play. Available options require trade-offs to be negotiated between different constituents to address the uneven distribution of the costs and benefits of adaptation.

Attention to “knowledge governance” provides a framework to sort through this diversity. “Knowledge governance” refers to the formal and informal rules and conventions that shape the ways we approach knowledge processes, such as creating, sharing, accessing, and using knowledge (after van Kerkhoff 2013). This encompasses the networks of actors that create and deploy knowledge, and the governance processes and structures that enable conservation actors to draw on academic and local knowledge of the social, political and ecological context.

Specifically, this recognizes that adaptation is strongly affected by:

-

Whose knowledge is drawn on to identify which (or whose) values, goals and objectives are embodied in climate adaptation strategies;

-

How knowledge about climate change is acquired, and used and by whom;

-

The formal or informal rules that shape the responses to that knowledge;

-

How those rules deal with uncertainty about preferences (e.g. new trade-offs, including reluctance to spend money), or knowledge (e.g. the technical feasibility or outcome from proposed responses);

-

Where barriers to effective climate adaptation might arise, and which actors have the agency to overcome them;

-

The processes that are in place to enable learning and how to strengthen them.

Understanding how knowledge about the social and ecological implications of climate change becomes (or fails to become) embedded in decision contexts is a core challenge. This requires broadening the focus beyond identifying what should happen to also understand how desired strategies can be achieved (Dovers and Hezri 2010; Erikson et al. 2015), to design interventions that can build capacity, support learning, and open up new pathways for adaptation (Wyborn et al. 2014). There is a critical need to refocus attention on the individual and institutional capacities to engage with and respond to short, medium and long-term change—and the trade-offs it presents. We suggest that this requires governance processes to enable broad stakeholder engagement in ongoing processes of learning, acting and reflection in the context of uncertainty.

Conclusion

While the adaptation research community increasingly acknowledges that climate adaptation is a socio-political endeavor—in the sense that it is concerned with contested societal decisions (Pelling 2011; O’Brien and Selboe 2015; Erikson et al. 2015)—the conservation community has been slower to recognize this. Conservation research and practice that focuses only on technical approaches and does not engage with the politics of who sets the rules, which values dominate or which knowledge will be used in decision-making will be poorly placed to accommodate significant and uncertain future changes in social and ecological systems.

Adaptation is not a one off event, rather, it is an ongoing process of learning, acting and reflecting in the context of uncertainty (Wise et al. 2014; Pelling 2011; O’Brien and Selboe 2015). A future-oriented conservation would work within, and where necessary, alter existing governance frameworks to expand the range of policy and management options through time. Shifting governance requires the conservation community to engage with the politics of conservation and adaptation, to engage with a diversity of knowledges and perspectives and to question the social and political values that underpin current efforts. Addressing this challenge is now an urgent priority.

References

Armitage D, Berkes F, Dale A, Kocho-Schellenberg E, Patton E (2011) Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Glob Environ Change 21:995–1004

Armsworth PR, Larson ER, Jackson ST, Sax DF, Simonin P, Blossey B, Shaw MR (2015) Are conservation organisations configured for effective adaptation to global change? Front Ecol Environ 13(3):163–169. doi:10.1890/130352

Chaffin BC, Gosnell H, Cosens BA (2014) A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: synthesis and future directions. 19(3)

Cosens B, Gunderson L, Allen C, Benson MH (2014) Identifying legal, ecological and governance obstacles, and opportunities for adapting to climate change. Sustainability 6(4):2338–2356. doi:10.3390/su6042338

Cross MS, Zavaleta ES, Bachelet D, Brooks ML, Enquist CA, Fleishman E, Tabor GM (2012) The Adaptation for Conservation Targets (ACT) framework: a tool for incorporating climate change into natural resource management. Environ Manage 50(3):341–351

Dovers SR, Hezri AA (2010) Institutions and policy processes: the means to the ends of adaptation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev 1:212–231

Dunlop M, Parris H, Ryan P, Kroon F (2013) Climate-ready conservation objectives: a scoping study. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast

Ensor J, Harvey B (2015) Social learning and climate change adaptation: evidence for international development practice. Wiley Interdiscip Rev 6(5):509–522

Eriksen SH, Nightingale AJ, Eakin H (2015) Reframing adaptation: the political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob Environ Change 35:523–533. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.014

Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J (2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour 30:441–473. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Glick P, Stein BA, Edelson NA (eds) (2011) Scanning the conservation horizon: a guide to climate change vulnerability assessment. National Wildlife Federation, Washington

Gorddard R, Wise R, Ware D, Dunlop M, Colloff M (2016) Values, rules and knowledge: adaptation as change in the decision context. Environ Sci Policy 57:60–69. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.12.004

Groves CR, Game ET, Anderson MG, Cross M, Enquist C, Ferdaña Z, Shafer SL (2012) Incorporating climate change into systematic conservation planning. Biodivers Conserv 21(7):1651–1671. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0269-3

Hagerman S, Dowlatabadi H, Chan KMA, Satterfield T (2010) Integrative propositions for adapting conservation policy to the impacts of climate change. Glob Environ Change 20:351–362

Heller NE, Hobbs RJ (2014) Development of a natural practice to adapt conservation goals to global change. Conserv Biol 00:1–9. doi:10.1111/cobi.12269

Holley C, Gunningham N, Shearing C (2012) The new environmental governance. Roughledge/Earthscan, London

Karpouzoglou T, Dewulf A, Clark J (2016) Advancing adaptive governance of social-ecological systems through theoretical multiplicity. Environ Sci Policy 57:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.11.011

Klein RJT, Juhola S (2014) A framework for Nordic actor-oriented climate adaptation research. Environ Sci Policy 40:101–115

Kujala H, Burgman MA, Moilanen A (2013) Treatment of uncertainty in conservation under climate change. Conserv Lett 6(2):73–85. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00299.x

Leach M, Scoones I, Stirling A (2010) Dynamic sustainabilities. Earthscan, London

Lemieux CJ, Scott DJ (2011) Changing Climate, Challenging Choices: Identifying and Evaluating Climate Change Adaptation Options for Protected Areas Management in Ontario. Canada. Environ Manage 48(4):675–690

Lemieux C, Thompson J, Dawson J, Schuster R (2013) Natural resource manager perceptions of agency performance on climate change. J Environ Manage 114:178–189

Leverington F, Lemos Costa K, Pavese H, Lisle A, Hockings M (2010) A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ Manage 46:685–698

Maru YT, Stafford Smith M (2014) Reframing adaptation pathways. Glob Environ Change 28:322–324

Mawdsley J (2011) Design of conservation strategies for climate adaptation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev 2(4):498–515

Mawdsley JR, O’Malley R, Ojima DS (2009) A review of climate-change adaptation strategies for wildlife management and biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 23:1080–1089

Moser SC, Ekstrom JA (2010) A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(51):22026–22031

O’Brien K, Selboe E (eds) (2015) The adaptive challenge of climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pacifici M, Foden WB, Visconti P, Watson JEM, Butchart SHM, Kovacs KM, Rondinini C (2015) Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nat Climate. Change 5(3):215–224

Pearson RG, Dawson TP (2003) Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Glob Ecol Biogeogr 12:361–371. doi:10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00042.x

Pelling M (2011) Adaptation to climate change: from resilience to transformation. Routledge, London

Reid H (2015) Ecosystem- and community-based adaptation: learning from community-based natural resource management. Climate Dev 5529(September):1–6

Rowland EL, Davison JE, Graumlich LJ (2011) Approaches to evaluating climate change impacts on species: a guide to initiating the adaptation planning process. Environ Manage 47(3):322–337

Schultz L, Folke C, Österblom H, Olsson P (2015) Adaptive governance, ecosystem management, and natural capital. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(24):7369–7374. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406493112

Seimon A, Watson J, Dave R, Gray E, Oglethorpe J 2011 A Review of Climate Change Adaptation Initiatives within the Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group Members. AWF, CI, Jane Goodall Institute, TNC, USAID, WCS, WRI and WWF, Arlington

Stein BA, Staudt A, Cross MS, Dubois NS, Enquist C, Griffis R, Pairis A (2013) Preparing for and managing change: climate adaptation for biodiversity and ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 11(9):502–510. doi:10.1890/120277

van Kerkhoff L (2013) Knowledge governance for sustainable development: a review. Chall Sustain 1(2):82–93

Watson J, Cross M, Rowland E, Joseph L, Rao M, Seimon A (2011) Planning for Species Conservation in a Time of Climate Change, Climate Change—Research and Technology for Adaptation and Mitigation. In: Blanco J. (ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-621-8, InTech, Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/climate-change-research-and-technology-for-adaptation-andmitigation/planning-for-species-conservation-in-a-time-of-climate-change

Watson JEM, Iwamura T, Butt N (2013) Mapping vulnerability and conservation adaptation strategies under climate change. Nat Climate Change 3(9):1–6

Williams BK, Brown ED (2014) Adaptive management: from more talk to real action. Environ Manage 53(2):465–479. doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0205-7

Willis KJ, Bhagwat SA (2009) Biodiversity and climate change. Science 326:806–807

Wise RM, Fazey I, Stafford Smith M, Park SE, Eakin HC, Archer Van Gardenen ERM, Campbell B (2014) Reconceptualising adaptation to climate change as part of pathways of change and response. Glob Environ Change 28:325–336

Wyborn C (2015) Co-productive governance: a relational framework for adaptive governance. Glob Environ Change 30:56–67. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.009

Wyborn C, Dovers S (2014) Prescribing adaptiveness in agencies of the state. Glob Environ Change 24:5–7. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.020

Wyborn C, Yung L, Murphy D, Williams D (2014) Situating adaptation: how governance challenges and perceptions of uncertainty influence adaptation in the Rocky Mountains. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0663-3

Yuen E, Jovicich SS, Preston BL (2012) Climate change vulnerability assessments as catalysts for social learning: four case studies in south-eastern Australia. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 18(5):567–590. doi:10.1007/s11027-012-9376-4

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue for their very useful feedback on this manuscript, which substantially improved the final version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Marie Vandewalle.

This is part of the special issue on Networking Biodiversity Knowledge.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wyborn, C., van Kerkhoff, L., Dunlop, M. et al. Future oriented conservation: knowledge governance, uncertainty and learning. Biodivers Conserv 25, 1401–1408 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1130-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1130-x