Abstract

Humanitarian operations are increasingly receiving attention due to the numerous recent disasters and crises caused by both natural and man-made events, from mass human exodus to pandemics such as COVID-19. The successful management of humanitarian supply chains requires the effective use of human resource practices, which in turn requires strong leadership in the so-called ‘soft side’ of management. This study aims to investigate the current status of research on the human aspects of humanitarian supply chains. Through a systematic and comprehensive literature review, encompassing an original codification and in-depth analysis of journal articles, this work provides a research agenda and a number of lessons concerning human resource management (HRM) in humanitarian operations. The main findings reveal that: (i) HRM impacts the ability of humanitarian organizations to adequately prevent, prepare for and respond to disasters; (ii) training programs for aid personnel are a vital aspect of humanitarian responsiveness; (iii) humanitarian operations require a workforce with a variety of soft and hard skills; (iv) lack of trained staff is one of the main challenges in this field; and (v) building relationships and strengthening networks can enlarge the human resource pool available. Therefore, the findings of this study and its proposed research agenda have implications for both theory and practice. In terms of theory, this work provides seven recommendations, representing opportunities for scholars to advance this body of knowledge. For humanitarian practitioners, this paper offers insightful lessons to guide them in the management of human resources in humanitarian operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A number of recent natural and man-made disasters have required humanitarian aid operations to overcome critical situations. Most recently, the COVID-19 outbreak has highlighted the importance of and urgent need for humanitarian actions for displaced and vulnerable populations during a crisis response (Queiroz et al. 2020; San Lau et al. 2020). In any humanitarian relief operation, logistics and supply chain management are critical and challenging factors (Dubey and Gunasekaran 2016; Soosay and Hyland 2015), requiring the engagement of various stakeholders such as governments, military, civil society, private companies, and international and national relief organizations (Yadav and Barve 2015).

Under humanitarian crisis conditions, there is no single organization which is capable of solving every ongoing problem or challenge. In this sense, it is always necessary to get different actors to work together in a network in order to effectively coordinate aid actions and to maximize efficiencies regarding costs and speed (Tomasini and Van Wassenhove 2009; Dubey et al. 2020). This therefore demands a humanitarian supply chain management strategy, a multilateral approach which involves managing the flow of supplies through international agencies and relief aid organizations, procuring resources from international and local agencies to deliver to the affected victims (Shareef et al. 2019; Yadav and Barve 2015) with agility and resilience (Altay et al. 2018).

Despite the importance of works aiming to find optimal solutions and models for humanitarian supply chains (Abualkhair et al. 2020; Anparasan and Lejeune 2019; Zhang et al. 2019), the management of humanitarian operations (HO) cannot be approached only from the perspective of the optimization of resources (Chandes and Paché 2010) for several reasons. Tomasini and Van Wassenhove (2009) argue that humanitarian supply chains (HSC) demand a vision that goes beyond delivering goods from one point to another. HSC management involves the coordination and collaboration of organizations with divergent natures and vocations in terms of services offered (Chandes and Paché 2010; Tomasini and Van Wassenhove 2009). Furthermore, each relief operation comes with its own distinct political and cultural realities (Chandes and Paché 2010).

In this context, it can be argued that human resource factors—also known as the ‘soft side’ of organizations (Dubey and Gunasekaran 2015)—are relevant for the success of HSC management, since this field involves dealing with different actors and cultures, political systems and government legislation (Pateman et al. 2013), and an adequate humanitarian workforce is essential to accomplish successful aid initiatives. Additionally, Siawsh et al. (2019) state that the focus of existing research has predominantly been on non-human aspects of humanitarian relief operations. Managing humanitarian supply chains is a ‘people business’ (Pateman et al. 2013). Nevertheless, little is known about the current state-of-the-art literature on the soft side of managing humanitarian supply chains (Dubey et al. 2019). Several literature reviews on HSC are available, addressing the role of technologies (Akter and Wamba 2019), HSC performance (Banomyong et al. 2019), applications of operations research (Behl and Dutta 2019) and relationship to theory (Muggy and Stamm 2014), among others, but none of these reviews have focused on the implications of human resource management for HSC. Therefore, it is relevant to explore and identify the role of human aspects in humanitarian supply chains. This study aims to address this gap by answering the following research question (RQ):

-

RQ: What is the current status of research on the human aspects of humanitarian supply chains?

To fulfill the objective of this study, the available literature was examined through a systematic and comprehensive review, encompassing in-depth analysis of journal articles and an original codification. Therefore, the main contributions and originality of this work lie in its systematization of several lessons concerning human resource management in humanitarian operations and the proposition of a novel research agenda.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a brief theoretical background to humanitarian supply chains and human resource management, while Sect. 3 explains the research methodology employed in the study. Section 4 reports the findings of the review and discussions. Finally, conclusions and implications are discussed in Sect. 5.

2 Brief conceptual background

2.1 Humanitarian supply chain management (HSCM)

Humanitarian crises are situations that require a high level of reliability and adaptation to meet the needs of vulnerable people (Chandes and Paché 2010), involving a complex network of participant organizations such as governments, military agencies, civil society, private companies, and relief organizations (Venkatesh et al. 2019; Yadav and Barve 2015). This network can be regarded as a humanitarian supply chain, and consists of a variety of actors aiming to provide maximum assistance to the affected population in terms of medical supplies, food, and other aid resources (Dubey and Gunasekaran 2016). Fosso Wamba (2020) further clarifies that HSCs include all activities associated with the preparation and management of necessary resources during natural or man-made disaster relief operations (Abidi et al. 2013). Humanitarian logistics has the objective of optimizing the process of delivering these resources to the victims (Chandes and Paché 2010). According to Nikbakhsh and Farahani (2011), the field of logistics in the context of humanitarian operations has attracted considerable attention due to the need for logistical systems that are capable of dealing with different kinds of disasters and disruption management.

The notion of profit is one of the main factors differentiating the humanitarian and commercial supply chains. While profit is the ultimate goal of the commercial sector, humanitarian organizations are guided by non-profit motives (Tomasini and Van Wassenhove 2009). Furthermore, the HSC is primarily reactive, whilst commercial supply chains are usually proactive (Dubey and Gunasekaran 2016).

The military is acknowledged as a significant actor in the humanitarian supply chain (Ozdamar et al. 2004), and the involvement of military forces in the provision of humanitarian aid in cases of conflict or natural disasters is not a new concept (Heaslip and Barber 2014). Military humanitarian actors have traditionally favored short-term lifesaving interventions with a clearly defined exit strategy (Rigby 2001, p. 957); hence the immediate response phase (Kovács and Spens 2008) to a natural disaster is considered to be the stage at which there is most likely to be a mix of military and non-military organizations working alongside one another (Pettit and Beresford 2005). This is due in no small part to the capacity-boosting availability of military resources, and to the military’s ability to cope with the unpredictability of demand and associated flexibility of response required (Rietjens et al. 2007). Moreover, the rapid response offered by the military, together with its structured command and control systems, is not within the capabilities of the majority of NGOs or other actors within the humanitarian supply chain (Kovács and Tatham 2010).

Considering that each disaster has its own characteristics, varying in types and levels of intensity (Tomasini and Van Wassenhove 2009), such situations involve a high level of uncertainty and demand different reactions and responses. According to Chandes and Paché (2010), humanitarian supply chain management is also challenging because it involves a critical time frame, requires the mobilization of team members from different origins, and has the urgency of coordinating numerous resources as quickly as possible.

The integrative nature of supply chains leads to the conclusion that supply chains are driven by human interaction and organizational relationships (McCarter et al. 2005). In this sense, the coordination of supply chain members and the development of SCM capacities must take into account the field of human resources (McAfee et al. 2002; Tomasini and Van Wassenhove 2009).

2.2 Human resource management (HRM)

Human resources (HR) are recognized as a critical feature of organizational competitiveness, playing a significant contribution in achieving organizational goals (Longoni et al. 2018; Jabbour et al. 2017), including those related to supply chain management (Gowen and Tallon 2003).

Human resource management involves mainly formal human resource policies and practices (Ivancevich 1995; Jackson and Schuler 1995), such as recruitment, selection, evaluation and talent management (Krishnan and Scullion 2017). Therefore, HRM attracts, develops, motivates, and retains employees who seek to achieve organizational goals, ensuring the effective functioning and survival of the organization (Ivancevich 1995; Jackson and Schuler 1995).

Nowadays, globalization, the liberalization of economies, the economic growth of emerging markets and demographic issues, such as the increasing movement of people around the world, are pushing HRM towards an international approach (Varma and Budhwar 2012). International human resource management (IHRM) is understood as incorporating the skills and knowledge required to create and implement policies and practices which aim to integrate globally dispersed human resources, while also taking into account the local differences and contextual particularities which affect the implementation of HR (Sparrow et al. 1994). IHRM becomes particularly important in the case of humanitarian supply chain management, in which it is necessary to manage humanitarian workers who come from different locations with distinct cultures, and who need to be recruited, selected, and properly prepared for crisis situations (Pateman et al. 2013).

Humanitarian supply chain workers, such as volunteers, managers and employees, operate in a complex environment which requires effective management practices (Pateman et al. 2013). Several different actors and stakeholders are involved in humanitarian operations, making policies and practices essential in order to guide and coordinate their actions (John et al. 2020). Mowafi et al. (2007), for instance, highlight the fact that humanitarian health workers are taking part in a multi-disciplinary endeavor and thus require proper training in broader humanitarian action to make them more effective in the field. Additionally, Coles et al. (2017) argue that further research is needed to improve understanding of the complex challenges faced by people working in relief operation management. Therefore, this ‘soft side’ (Dubey and Gunasekaran 2015) of humanitarian supply chains is an important topic for academics as well as practitioners, and deserves to a systematization of its state-of-the-art literature.

3 Methodological approach

An original systematic literature review was conducted using a combination of the approaches employed by Fiorini and Jabbour (2017), Gaur and Kumar (2018), and Jabbour et al. (2019), as summarized in Fig. 1.

The Scopus database was chosen to identify relevant studies for this review. According to Harzing and Alakangas (2016), Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) are the two most widely used academic databases in the world, providing fairly similar results. However, Brzezinski (2015) explains that the Scopus database is advantageous because it indexes about 70% more sources than WoS, providing comprehensive coverage of the latest literature, including most of the papers available in the WoS database. Moreover, Harzing and Alakangas (2016) show that Scopus usually presents higher citation levels in the Engineering field. The process of selecting the sample of articles from the Scopus database is summarized in Table 1.

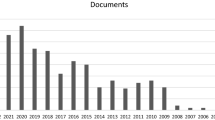

An initial search, using the following query, resulted in 205 documents: [TITLE-ABS-KEY ("humanitarian supply chain") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("humanitarian logistics") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("humanitarian operations") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("human resource") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("personnel") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("people")]. This search focused on finding studies related to human resource management in humanitarian supply chains. Therefore, the keywords selected reflect this focus, first by the use of the key terms “humanitarian supply chain” and “humanitarian logistics”, as used in the review of Jabbour et al. (2019), since the supply chain is regarded as the backbone of humanitarian operations (Lewin et al. 2018; Besiou and Van Wassenhove 2020). Second, in order to specify findings related to human resource management, we used the keywords “human resource”, “personnel”, and “people”. Considering that the initial results from the academic database were not too broad and in order to ensure a larger coverage of the relevant literature, it was decided to expand the query by adding the keyword “humanitarian operations” and also not to limit the time span of the sample.

The sample was then narrowed to 144 documents by applying the following criteria: selecting only articles and reviews from journals and those written in English. In the subsequent step, the remaining documents were analyzed and selected after reading through their abstracts, resulting in a sample of 58 articles.

Next, a coding scheme was developed, as shown in Table 2. This scheme was based on five dimensions, which were categorized using a combination of numbers and letters, as explained below:

-

Category 1 refers to the degree of economic maturity of the context under consideration and was categorized using letter codes A–C;

-

Category 2 indicates the focus of the article, which could have human aspects as the primary discussion of the article (A), or have human aspects as a secondary discussion only (B)—that is, HR was not the main focus of these studies;

-

Category 3 is related to the research method used and was categorized using letter codes A–J;

-

Category 4 refers to the human resource practices that are associated with humanitarian supply chain management in the article, coded from A to G;

-

Category 5 identifies the actors of the humanitarian supply chain involved in the study, including government, aid agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), private companies and military agencies, coded from A to E respectively, with code F used if it was not specified.

After reading the selected articles in full and applying the coding scheme, the final sample consisted of 39 articles. The publication period for the sample analyzed ranged from 2011 to 2020. During the full reading process, those articles which did not address human aspects in the humanitarian supply chain or those that were unavailable to download were eliminated, leading to the final reduction from 58 to 39 articles. Lastly, by delving into the content of each article, this work was able to provide a comprehensive picture of the state-of-the-art literature on human resource management in humanitarian supply chains and to develop an original research agenda. Through our analysis of the classifications and coding, seven recommendations for future studies emerged, and by applying an inductive analysis process to the reviewed articles, we identified five lessons for human resource management in humanitarian operations (Gosling et al. 2016).

Table 3 displays the classification of the 39 articles analyzed.

4 Results and discussions

4.1 Results and recommendations

This section reports the results of the classification and coding presented in Table 3. Additionally, Table 4 presents a summary of the contributions of each article analyzed.

The first category by which we classified the articles refers to the economic context analyzed in the studies. The analysis showed that 21 out of the 39 articles (53.8%) addressed non-mature economies, while 5 documents focused on mature economies (Fig. 2). According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA 2018, www.unocha.org), in 2017 the top five countries with the highest number of people affected by natural disasters were India, China, Bangladesh, Cuba and Vietnam, while those with the most newly displaced people due to conflicts were Syria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

In this sense, it is to be expected that these studies address real situations in countries which have ongoing circumstantial challenges or have experienced humanitarian crises. However, only three studies (7.7%) focused on studying the contexts of both mature and less-mature economies. Therefore, it is recommended that more studies approach human factors in humanitarian supply chains while considering developed and developing economies simultaneously. As previously mentioned, HSCs primarily have a reactive strategy; nonetheless, ensuring a successful operation requires advance planning (Balcik et al. 2010; Dubey and Gunasekaran 2016), which must involve not only human resources from local communities, but also international aid personnel. Therefore, the first recommendation of this study is:

-

R1: Explore human resource management in humanitarian supply chains in mature and less-mature economies simultaneously in order to understand the preparedness required for local and international personnel.

The second coding category aimed to investigate the focus of the articles, concerning whether each article approached the HR aspects of humanitarian supply chain management as the main topic of the article, or as an adjacent discussion. Figure 3 shows that nearly 70% of these studies, representing 27 out of 39 documents, did not analyze human resource factors as the main focus of their research on HSCs. This finding corroborates the study of Siawsh et al. (2019), which stated that the focus of HSC studies has been mostly on non-human aspects. Furthermore, McLachlin and Larson (2011) clarify that literature aimed at commercial supply chains might contain useful guidance on relationships including HR aspects, which could be adapted and further explored in humanitarian supply chains. This leads us to the second recommendation:

-

R2: Analyze the direct contributions of human resources practices to humanitarian supply chain management, identifying potential useful lessons from commercial supply chain research as well as that specifically related to HSC.

Figure 4 displays the results of Category 3. This third category concerned the research method adopted in the studies. The analysis shows that most of the articles that address human aspects in HSC have adopted a qualitative approach (67%); among those, 38% used the interview method, while another 23% applied the case study strategy. From the whole sample, 18% used a quantitative approach, and only 5 out of 39 studies applied the survey method. Regarding modeling, about 26% of the papers in the sample chose this method. Therefore, the majority of the studies have either conducted interviews or performed analysis of barriers and critical success factors for humanitarian supply chains (e.g. Botchie et al. (2019), Kabra and Ramesh (2015), Kabra et al. (2015), Ghasemian Sahebi et al. (2017), Yadav and Barve (2015), among others). Very few studies have adopted quantitative methods, such as surveys. Therefore, the third suggestion is:

-

R3: Conduct quantitative studies using the survey method to explore the relationship between human resource management and humanitarian supply chains.

The fourth category analyzes the human resource management practices which are addressed in the studies. In the case of studies which address multiple practices, more than one code was assigned to the article. Figure 5 shows the frequency for each factor separately. Among all the HRM factors categorized, training and development were the most frequently addressed among the studies (24 studies), followed by skills and competencies (19 articles). As can be seen in Table 3, these two codes (4B and 4C) were most often addressed together in the articles. On the other hand, performance appraisal and management, followed by teamwork, motivation, and retention were the least studied practices. In addition, none of the works analyzed all the practices categorized. The study by Polater (2020) was the only one to mention at least five practices; nonetheless, HRM was not the focus of this study. Therefore, the fourth recommendation is:

-

R4: Expand this area of study to verify how each human resource practice can contribute to the management and performance of humanitarian supply chains.

In this regard, Heaslip et al. (2019) highlight that it is essential to consider that contextual factors can lead to differences in human resources requirements for HSCs. Tatham et al. (2013) and Stuns and Heaslip (2019) explain, for example, that training content should be tailored to the conditions of specific countries, since each response operation is different due to different cultural and political contexts and types of disasters. However, understanding how these contingency factors affect the various HRM practices in humanitarian operations is still an underexplored area. Thus, we recommend:

-

R5: Examine how contextual factors affect human resource management practices in humanitarian supply chains through the lens of contingency theory.

Considering the HRM practices identified in the studies analyzed, some important lessons can be provided. First, there is a general awareness that human resource management is a critical factor for HSCM because it impacts on the ability of humanitarian organizations to adequately prevent, prepare for and respond to disasters (Botchie et al. 2019; Rajakaruna and Wijeratne 2019). In particular, HRM is a core strategy during preparedness activities for disaster response, helping to mitigate risks and to develop the capacities needed for humanitarian workers (Yadav and Barve 2015; Yadav and Barve 2019).

In this vein, the second lesson concerns the most frequently addressed HR practice, which was training and development. Training programs for aid personnel are a vital aspect of humanitarian actions and responsiveness (Tint et al. 2015; Jahre and Fabbe-Costes 2015). Our findings reveal that pre-departure training is considered fundamental by the workforce in order to ensure successful aid activities and to handle the challenges that emerge during humanitarian missions (Jahre and Fabbe-Costes 2015; Lamb 2018; Mari Ainikki Anttila 2014; Pateman et al. 2013). The existence of courses and training is also important to improve the coordination of humanitarian supply chain members (Kabra and Ramesh 2015). Some specific examples of training initiatives were identified, such as using applied improvisation as a tool to develop adaptive skills (Tint et al. 2015), and distance learning for training humanitarian staff and disseminating humanitarian principles to personnel (Bollettino and Bruderlein 2008).

The development of capacities through training leads us to the third lesson: humanitarian operations require multi-skilled and flexible personnel with a variety of soft and hard skills (Lamb 2018; Rajakaruna and Wijeratne 2019; Rajakaruna et al. 2017; Suresh et al. 2019). Nonetheless, the scope of training programs has generally focused more on technical abilities and logistics skills, rather than on the development of soft skills, such as relationship building, coordination, cultural adaptation, and resilience (Stuns and Heaslip 2019; Suresh et al. 2019). Therefore, we suggest researchers:

-

R6: Investigate the role of human resource management practices for capacity building in humanitarian operations.

The fourth lesson relates to the barriers to human resource management in humanitarian supply chains. The main challenges found were a lack of trained staff, a shortage of skilled humanitarians, high turnover and limited human resources in local agencies (Ghasemian Sahebi et al. 2017; Pateman et al. 2013; Sharifi-Sedeh et al. 2020; Yadav and Barve 2016). Regarding motivation and retention practices, Polater (2020) argues that financial incentives are not seen as a key factor in the humanitarian workforce, but that building organizational culture and a sense of social responsibility among all supply chain members are more effective strategies.

The fifth lesson addresses a proposed way to overcome the barrier of limited availability of human resources in local agencies: building relationships and strengthening multi-sector local logistics networks. It is suggested that organizations strengthen local networks and establish closer ties with local private and public enterprises, civil society and other local logistics companies in order to enlarge the national human resource pool of logisticians available to satisfy the humanitarian demand (Heaslip et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2018; McLachlin and Larson 2011).

Finally, the last classification of the studies relates to the type of humanitarian actor observed in each article. Figure 6 shows that 13 out of 39 papers (33%) did not specify any type of organization. Among those studies that did analyze humanitarian supply chain actors, the majority focused on aid agencies and non-governmental organizations (17 and 16 studies, respectively). Considering that none of the studies approached all types of humanitarian supply chain actors and focused fundamentally on HRM aspects, it is recommended to:

-

R7: Study how HRM practices support the coordination of the various humanitarian supply chain actors.

4.2 Implications for theory and practice

In terms of implications for theory, this work has systematized the findings and lessons concerning the ‘soft side’ of managing humanitarian supply chains available in the extant literature and provided several research avenues for academics. While other disciplines have previous literature reviews dedicated to understanding their role in the management of HSC (Akter and Wamba 2019; Banomyong et al. 2019; Behl and Dutta 2019; Muggy and Stamm, 2014; Jabbour et al. 2019), so far, little has been known about the current state-of-the-art literature on human resource management in humanitarian supply chains. The future research directions recommended in this study show that there is plenty of room for researchers to further develop our understanding of how human resource practices can affect the performance, responsiveness, and coordination of humanitarian supply chains.

Regarding the implications for managers of HSCs, this work highlights that the proper management of human aspects can have a decisive role in the effectiveness of HSC operations and response actions to natural and man-made disasters. For example, HRM practices such as offering training programs are a fundamental strategy to develop capacities and prepare workers for humanitarian actions (Tint et al. 2015; Jahre and Fabbe-Costes 2015; Yadav and Barve 2015; Yadav and Barve 2019). Practitioners must be aware that humanitarian supply chains require staff members with multiple hard and soft skills. Additionally, the development of soft skills is seen as key to coping with the factors involved in HSC, such as the coordination of several actors and contextual aspects related to the different political and cultural contexts faced in each operation (Chandes and Paché 2010).

5 Final remarks

5.1 Research agenda framework

This study investigated the current status of research on human aspects in humanitarian supply chains, employing a systematic literature review. From the codification and in-depth analysis of 39 journal articles emerged recommendations towards a research agenda and a number of lessons concerning human resource management in humanitarian operations. Therefore, this article has made contributions to both literature and practice.

This work provides an original research agenda, composed of seven recommendations. Each of the following recommendations represent an opportunity for scholars to advance the body of knowledge on HRM in humanitarian operations. First, it is suggested to explore human resource management in humanitarian supply chains simultaneously in mature and less-mature economies to understand the preparedness required for local and international personnel. The second recommendation is to analyze the direct contributions of human resources practices to humanitarian supply chain management, identifying potential useful lessons from commercial supply chain research as well as specifically in HSC. Furthermore, it is important that future studies expand knowledge concerning how each human resource practice can support the management and performance of humanitarian supply chains.

Next, regarding the methodological approach, it is necessary to conduct quantitative studies utilizing the survey method to explore the relationship between human resource management and humanitarian supply chains. Additionally, little is currently known about the influence of contextual factors on human resource management practices in humanitarian supply chains, especially through the lens of contingency theory. Another topic that should be further investigated is the role of HRM practices for capacity building in humanitarian operations. The final recommendation is to investigate the coordination of multiple humanitarian supply chain actors through the support of HRM practices.

Anchored in the research agenda mentioned before, it is possible to propose an original research framework capable of addressing the scarcest dimensions of the current state-of-the-art literature on the ‘soft side’ of humanitarian supply chains. Figure 7 shows a selection of research topics that could direct studies to approach human resources management as the primary focus of discussion in HSC works—especially considering how little HRM practices have been addressed in previous articles—covering areas such as performance appraisal and management, teamwork, motivation, and retention. Moreover, the role of HRM for building the capacities needed for HSCs and to coordinate multiple actors, including less studied agents such as the military, are suggested future research directions. Forthcoming studies on HR and HSC should consider the influence of contextual factors, as well as addressing HR preparedness for humanitarian actions in distinct economic contexts.

5.2 Lessons for practitioners

For humanitarian practitioners, our study offers five lessons to guide them in the management of human resources in disaster relief situations. First, human resource management is a critical factor for humanitarian supply chains because it impacts the ability of humanitarian organizations to adequately prevent, prepare for, and respond to disasters. In this sense, the second lesson points out that training programs for aid personnel are a vital aspect for humanitarian actions and responsiveness; in particular, pre-departure training is considered fundamental by the workforce. Third, it is equally important to recognize that HO requires a workforce with a variety of soft and hard skills. Nonetheless, training programs have predominantly covered technical and logistical skills rather than soft skills; relationship building, coordination, cultural adaptation and resilience should be more frequently addressed in training. Fourth, the main challenges in HRM for humanitarian operations include a lack of trained staff, a shortage of skilled humanitarians, high turnover and limited human resources in the local agencies. The fifth lesson states that building relationships and strengthening multi-sector local logistics networks with private and public organizations, local civil society and other local logistics companies is a pathway to enlarge the national human resource pool available, considering the common HR shortage scenario.

5.3 Limitations

The limitations of this research should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, systematic reviews are by necessity based on search terms that might not be extensive enough to capture all the available literature on the topic. Moreover, the search for journal articles was performed only using the Scopus database. Finally, the analyses of the articles required a cognitive process of reading, filtering, and coding studies, bringing a subjective perspective to determining the final sample and codification.

References

Abidi, H., de Leeuw, S., & Klumpp, M. (2013). Measuring success in humanitarian supply chains. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 2(8), 31–39.

Abualkhair, H., Lodree, E. J., & Davis, L. B. (2020). Managing volunteer convergence at disaster relief centers. International Journal of Production Economics, 220, 107399.

Akhtar, P., Marr, N. E., & Garnevska, E. V. (2012). Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: chain coordinators. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Akter, S., & Wamba, S. F. (2019). Big data and disaster management: a systematic review and agenda for future research. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1–2), 939–959.

Altay, N., Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2018). Agility and resilience as antecedents of supply chain performance under moderating effects of organizational culture within the humanitarian setting: A dynamic capability view. Production Planning & Control, 29(14), 1158–1174.

Anparasan, A., & Lejeune, M. (2017). Analyzing the response to epidemics: concept of evidence-based Haddon matrix. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Anparasan, A., & Lejeune, M. (2019). Resource deployment and donation allocation for epidemic outbreaks. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1), 9–32.

Arroyo, D. M. (2014). Blurred lines: Accountability and responsibility in post-earthquake Haiti. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 30(2), 110–132.

Baharmand, H., Comes, T., & Lauras, M. (2017). Managing in-country transportation risks in humanitarian supply chains by logistics service providers: Insights from the 2015 Nepal earthquake. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 24, 549–559.

Balcik, B., Beamon, B. M., Krejci, C. C., Muramatsu, K. M., & Ramirez, M. (2010). Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: Practices, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Production Economics, 126(1), 22–34.

Banomyong, R., Varadejsatitwong, P., & Oloruntoba, R. (2019). A systematic review of humanitarian operations, humanitarian logistics and humanitarian supply chain performance literature 2005 to 2016. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1–2), 71–86.

Behl, A., & Dutta, P. (2019). Humanitarian supply chain management: A thematic literature review and future directions of research. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1), 1001–1044.

Besiou, M., & Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2020). Humanitarian operations: A world of opportunity for relevant and impactful research. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 22(1), 135–145.

Bollettino, V., & Bruderlein, C. (2008). Training humanitarian professionals at a distance: Testing the feasibility of distance learning with humanitarian professionals. Distance Education, 29(3), 269–287.

Botchie, D., Damoah, I. S., & Tingbani, I. (2019). From preparedness to coordination: operational excellence in post-disaster supply chain management in Africa. Production Planning & Control, 1–18.

Brzezinski, M. (2015). Power laws in citation distributions: Evidence from Scopus. Scientometrics, 103(1), 213–228.

Chandes, J., & Paché, G. (2010). Investigating humanitarian logistics issues: from operations management to strategic action. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management.

Coles, J. B., Zhang, J., & Zhuang, J. (2017). Bridging the research-practice gap in disaster relief: Using the IFRC Code of Conduct to develop an aid model. Annals of Operations Research, 1–21.

Dubey, R., & Gunasekaran, A. (2015). Exploring soft TQM dimensions and their impact on firm performance: Some exploratory empirical results. International Journal of Production Research, 53(2), 371–382.

Dubey, R., & Gunasekaran, A. (2016). The sustainable humanitarian supply chain design: Agility, adaptability and alignment. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 19(1), 62–82.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., & Papadopoulos, T. (2019). Disaster relief operations: Past, present and future. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1–2), 1–8.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D. J., Graham, G., Giannakis, M., & Mishra, D. B. (2020). Agility in Humanitarian Supply Chain: An organizational information processing perspective and relational view. Annals of Operations Research.

Fiorini, P. D. C., & Jabbour, C. J. C. (2017). Information systems and sustainable supply chain management towards a more sustainable society: Where we are and where we are going. International Journal of Information Management, 37(4), 241–249.

Fosso Wamba, S. (2020). Humanitarian supply chain: a bibliometric analysis and future research directions. Annals of Operations Research, 1–27.

Garcia, C., Rabadi, G., & Handy, F. (2018). Dynamic resource allocation and coordination for high-load crisis volunteer management. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Gaur, A., & Kumar, M. (2018). A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 280–289.

GhasemianSahebi, I., Arab, A., & Moghadam, M. R. S. (2017). Analyzing the barriers to humanitarian supply chain management: a case study of the Tehran Red Crescent Societies. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 24, 232–241.

Gonçalves, P. (2011). Balancing provision of relief and recovery with capacity building in humanitarian operations. Operations Management Research, 4(1–2), 39–50.

Gosling, J., Jia, F., Gong, Y., & Brown, S. (2016). The role of supply chain leadership in the learning of sustainable practice: Toward an integrated framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1458–1469.

Gowen, C. R., & Tallon, W. J. (2003). Enhancing supply chain practices through human resource management. Journal of Management Development.

Gralla, E., Goentzel, J., & Chomilier, B. (2015). Case study of a humanitarian logistics simulation exercise and insights for training design. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Harzing, A. W., & Alakangas, S. (2016). Google Scholar, Scopus and the web of science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics, 106(2), 787–804.

Heaslip, G, & Barber, E. (2014). Using the military in disaster relief: Systemising challenges and opportunities. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 4(1).

Heaslip, G., Vaillancourt, A., Tatham, P., Kovács, G., Blackman, D., & Henry, M. C. (2019). Supply chain and logistics competencies in humanitarian aid. Disasters, 43(3), 686–708.

Ivancevich, J. M. (1995). Human resource management. Chicago: Irwin.

Jabbour, C. J. C., Mauricio, A. L., & Jabbour, A. B. L. D. S. (2017). Critical success factors and green supply chain management proactivity: shedding light on the human aspects of this relationship based on cases from the Brazilian industry. Production Planning & Control, 28(6–8), 671–683.

Jabbour, C. J. C., Sobreiro, V. A., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., de Souza Campos, L. M., Mariano, E. B., & Renwick, D. W. S. (2019). An analysis of the literature on humanitarian logistics and supply chain management: paving the way for future studies. Annals of Operations Research, 1–19.

Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1995). Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments. Annual Review of Psychology, 46(1), 237–264.

Jahre, M., Dumoulin, L., Greenhalgh, L. B., Hudspeth, C., Limlim, P., & Spindler, A. (2012). Improving health in developing countries: reducing complexity of drug supply chains. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Jahre, M., & Fabbe-Costes, N. (2015). How standards and modularity can improve humanitarian supply chain responsiveness. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Jahre, M., Kembro, J., Rezvanian, T., Ergun, O., Håpnes, S. J., & Berling, P. (2016a). Integrating supply chains for emergencies and ongoing operations in UNHCR. Journal of Operations Management, 45, 57–72.

Jahre, M., Pazirandeh, A., & Van Wassenhove, L. (2016b). Defining logistics preparedness: a framework and research agenda. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

John, L., Gurumurthy, A., Mateen, A., & Narayanamurthy, G. (2020). Improving the coordination in the humanitarian supply chain: exploring the role of options contract. Annals of Operations Research, 1–26.

Kabra, G., & Ramesh, A. (2015). Analyzing drivers and barriers of coordination in humanitarian supply chain management under fuzzy environment. Benchmarking: An International Journal.

Kabra, G., Ramesh, A., & Arshinder, K. (2015). Identification and prioritization of coordination barriers in humanitarian supply chain management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 13, 128–138.

Kovács, G., & Spens, K. M. (2008). Humanitarian Logistics Revisited published. In Northern Lights in Logistics and Supply Chain Management. Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Kovács, G., & Tatham, P. (2010). What is special about a humanitarian logistician? A survey of logistics skills and performance. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 11(3), 32–41.

Krishnan, T. N., & Scullion, H. (2017). Talent management and dynamic view of talent in small and medium enterprises. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 431–441.

Lamb, D. (2018). Factors affecting the delivery of healthcare on a humanitarian operation in West Africa: A qualitative study. Applied Nursing Research, 40, 129–136.

Lewin, R., Besiou, M., Lamarche, J. B., Cahill, S., & Guerrero-Garcia, S. (2018). Delivering in a moving world… looking to our supply chains to meet the increasing scale, cost and complexity of humanitarian needs. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Longoni, A., Luzzini, D., & Guerci, M. (2018). Deploying environmental management across functions: the relationship between green human resource management and green supply chain management. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 1081–1095.

Lu, Q., Goh, M., & De Souza, R. (2013). Learning mechanisms for humanitarian logistics. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Mari Ainikki Anttila, U. (2014). Human security and learning in crisis management. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Meduri, D. D., & Srinivas Rao, D. (2019). Preferred humanitarian competencies: An empirical exploration. International Journal of Management and Business Research, 9(1), 27–40.

McAfee, R. B., Glassman, M., & Honeycutt, E. D., Jr. (2002). The effects of culture and human resource management policies on supply chain management strategy. Journal of Business Logistics, 23(1), 1–18.

McCarter, M. W., Fawcett, S. E., & Magnan, G. M. (2005). The effect of people on the supply chain world: Some overlooked issues. Human Systems Management, 24(3), 197–208.

McLachlin, R., & Larson, P. D. (2011). Building humanitarian supply chain relationships: lessons from leading practitioners. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Mowafi, H., Nowak, K., & Hein, K. (2007). Facing the challenges in human resources for humanitarian health. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 22(5), 351.

Muggy, L., & Stamm, J. L. H. (2014). Game theory applications in humanitarian operations: a review. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Nikbakhsh, E., & Farahani, R. Z. (2011). Humanitarian logistics planning in disaster relief operations. Logistics Operations and Management: Concepts and Models, 291.

Ozdamar, L., Ekinci, E., & Kucukyazici, B. (2004). Emergency logistics planning in natural disasters. Annals of Operations Research, 129, 217–245.

Pateman, H., Hughes, K., & Cahoon, S. (2013). Humanizing humanitarian supply chains: A synthesis of key challenges. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 29(1), 81–102.

Pettit, S., & Beresford, A. (2005). Emergency relief logistics: An evaluation of military, non-military and composite response models. International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications, 8(4), 313–332.

Polater, A. (2020). Airports’ role as logistics centers in humanitarian supply chains: A surge capacity management perspective. Journal of Air Transport Management, 83, 101765.

Queiroz, M. M., Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Wamba, S. F. (2020). Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Annals of Operations Research, 1–38.

Rajakaruna, S., & Wijeratne, A. W. (2019). Effectiveness of logistics skills to individual performance: Challenges to Sri Lankan humanitarian sector. International Journal of Learning and Change, 11(4), 324–346.

Rajakaruna, S., Wijeratne, A. W., Mann, T. S., & Yan, C. (2017). Identifying key skill sets in humanitarian logistics: Developing a model for Sri Lanka. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 24, 58–65.

Rietjens, J. H., Voordijk, H., & De Boer, S. J. (2007). Co-ordinating humanitarian operations in peace support missions. Disaster Prevention and Management, 16(1), 56–69.

Rigby, A. (2001). Humanitarian assistance and conflict management: The view from the non-governmental sector. International Affairs, 77(4), 957–966.

San Lau, L., Samari, G., Moresky, R. T., Casey, S. E., Kachur, S. P., Roberts, L. F., & Zard, M. (2020). COVID-19 in humanitarian settings and lessons learned from past epidemics. Nature Medicine, 1–2.

Shafiq, M., & Soratana, K. (2020). Lean readiness assessment model–a tool for Humanitarian Organizations' social and economic sustainability. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Sharifi-Sedeh, M., Khorasani-Zavareh, D., Ardalan, A., & Torabi, S. A. (2020). Factors behind the prepositioning of relief items in Iran: A qualitative study. Injury.

Shareef, M. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Mahmud, R., Wright, A., Rahman, M. M., Kizgin, H., & Rana, N. P. (2019). Disaster management in Bangladesh: Developing an effective emergency supply chain network. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1), 1463–1487.

Sheppard, A., Tatham, P., Fisher, R., & Gapp, R. (2013). Humanitarian logistics: enhancing the engagement of local populations. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Siawsh, N., Peszynski, K., Young, L., & Vo-Tran, H. (2019). Exploring the role of power on procurement and supply chain management systems in a humanitarian organisation: a socio-technical systems view. International Journal of Production Research, 1–26.

Soosay, C. A., & Hyland, P. (2015). A decade of supply chain collaboration and directions for future research. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal.

Sparrow, P., Schuler, R. S., & Jackson, S. E. (1994). Convergence or divergence: Human resource practices and policies for competitive advantage worldwide. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5(2), 267–299.

Stuns, K. K., & Heaslip, G. (2019). Effectiveness of humanitarian logistics training. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Suresh, M., Ganesh, S., & Raman, R. (2019). Modelling the factors of agility of humanitarian operations. International Journal of Agile Systems and Management, 12(2), 108–123.

Tatham, P., & Rietjens, S. (2016). Integrated disaster relief logistics: a stepping stone towards viable civil–military networks? Disasters, 40(1), 7–25.

Tatham, P., Altay, N., Bölsche, D., Klumpp, M., & Abidi, H. (2013). Specific competencies in humanitarian logistics education. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Tint, B. S., McWaters, V., & van Driel, R. (2015). Applied improvisation training for disaster readiness and response. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Tomasini, R. M., & Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2009). From preparedness to partnerships: Case study research on humanitarian logistics. International Transactions in Operational Research, 16(5), 549–559.

UNOCHA—United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2018). World humanitarian data and trends. Available at: https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/WHDT2018_web_final_spread.pdf

Varma, A., & Budhwar, P. (2012). International human resource management in the Indian context. Journal of World Business, 47(2), 157–158.

Venkatesh, V. G., Zhang, A., Deakins, E., Luthra, S., & Mangla, S. (2019). A fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS approach to supply partner selection in continuous aid humanitarian supply chains. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1), 1517–1550.

Yadav, D. K., & Barve, A. (2015). Analysis of critical success factors of humanitarian supply chain: An application of Interpretive Structural Modeling. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 12, 213–225.

Yadav, D. K., & Barve, A. (2016). Modeling post-disaster challenges of humanitarian supply chains: A TISM approach. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 17(3), 321–340.

Yadav, D. K., & Barve, A. (2019). Prioritization of cyclone preparedness activities in humanitarian supply chains using fuzzy analytical network process. Natural Hazards, 97(2), 683–726.

Zhang, J., Wang, Z., & Ren, F. (2019). Optimization of humanitarian relief supply chain reliability: A case study of the Ya’an earthquake. Annals of Operations Research, 283(1), 1551–1572.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Camargo Fiorini, P., Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J., Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B. et al. The human side of humanitarian supply chains: a research agenda and systematization framework. Ann Oper Res 319, 911–936 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-03970-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-03970-z