Abstract

Psychosocial function and adherence to antiretroviral regimen are key factors in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease management. Alexithymia (AL) is a trait deficit in the ability to identify and describe feelings, emotions and bodily sensations. A structural equation model was used to test whether high levels of AL indirectly relate to greater non-adherent behavior and HIV disease severity via psychosocial dysfunction. Blood draws for HIV-1 viral load and CD4 T-lymphocyte, along with psychosocial surveys were collected from 439 HIV positive adults aged 18–73 years. The structural model supports significant paths from: (1) AL to non-active patient involvement, psychological distress, and lower social support, (2) psychological distress and non-active involvement to non-adherent behavior, and (3) non-adherence to greater HIV disease severity (CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05). A second model confirmed the intermediary effect of greater patient assertiveness on the path from AL to social support and non-active patient involvement (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05). Altogether, AL is indirectly linked with HIV disease management through it's association with poor psychosocial function, however greater patient assertiveness buffers the negative impact of AL on relationship quality with healthcare providers and members of one's social support network.

Resumen

La función psicosocial y la adherencia a tratamiento antirretroviral son factores clave para virus de inmunodeficiencia humana de control de enfermedades (VIH). La alexitimia (AL) es un déficit rasgo en la capacidad de identificar y describir los sentimientos, emociones y sensaciones corporales. Modelo estructural se utilizó para probar si los altos niveles de AL se relacionan indirectamente con mayor comportamiento no-adherencia y gravedad de la enfermedad del VIH a través de la disfunción psicosocial. La extracción de sangre para el VIH-1 la carga viral y CD4 de los linfocitos T, junto con encuestas psicosociales se obtuvieron de 439 adultos con VIH de 18 a 73 años. El modelo estructural admite rutas importantes de: (1) AL a la participación no activa del paciente, la angustia psicológica y menor apoyo social, (2) la angustia y no activa participación a un comportamiento no adhesión, y (3) la falta de adherencia a una mayor gravedad de la enfermedad del VIH (CFI = .97, RMSEA = 0,04, SRMR = 0,05). Un segundo modelo confirmó el efecto intermedio de una mayor asertividad en el efecto de AL, el apoyo social y la participación de los pacientes no activo (CFI = .94, RMSEA = 0,04, SRMR = 0,05). En total, AL se asocia indirectamente con la gestión de la enfermedad del VIH a través de una pobre función psicosocial, aún mayor asertividad paciente puede amortiguar el efecto negativo de AL en la calidad de la relación con los proveedores de salud y los miembros de la red de apoyo social.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an important health behavior that is related to reduced chance of drug resistance and lower viremia in persons living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1–4]. Although substance abuse is the most commonly associated with non-adherence behavior, a number of psychosocial factors have also been implicated [5–8]. Psychological distress, operationalized as HIV-related stress, anxiety and depression, has been linked to greater immune dysfunction and HIV disease severity [9–11]. A number of studies suggest non-adherence to anti-retroviral therapy is an intermediary factor linking greater depression to HIV disease severity [12–14]. The complete spectrum of post-traumatic, acute, and chronic HIV-related stressors are also implicated in lower adherence to ART [15–22]. In addition, greater levels of anxiety also predict lower medication adherence in persons living with HIV [23, 24]. Interpersonal functioning with healthcare providers and others within the social support network are important factors of psychosocial functioning that predict health and behavioral outcomes in persons living with HIV/AIDS. For example, greater availability of social support is shown to predict higher adherence to ART both independent of psychological distress [25–27], or as a function thereof [28, 29]. Within a patient-centered care paradigm [30] the doctor-patient relationship is considered to be a critical factor for HIV disease management. Greater communication, collaboration, and trust between doctor and patient have all been linked with stable adherence to anti-retroviral regimen [31–36], and more recently long-term survival in HIV-infected individuals [5]. Altogether, adherence to anti-retroviral therapy is an important factor in HIV disease management and a host of psychosocial factors may interact to alter adherence behaviors which may subsequently increase the rate of HIV disease progression.

There has been an increase in the study of trait alexithymia (AL) within the context of HIV disease management and psychosocial function [37–42]. Persons with high levels of trait AL demonstrate lower cognitive assimilation of feelings, physical symptoms, and emotions, and often demonstrate confusion, externalization, and vagueness when asked about their affective state [43–45]. The prevalence of trait AL in population studies is estimated to be around 6 % and is largely attributed to genetic, neurobiological and sociodemographic factors [46–51]. The ability to identify and describe feelings may influence psychosocial functioning in many ways. Studies suggest that higher levels of the trait are consistently linked with chronic unresolved stress [52, 53] and symptoms of depression and anxiety [54–56]. Alexithymia has also been linked to irregular use and poorer perception of social support [57–59]. Others have shown the trait to interact with availability of social support to predict distress levels [57, 60]. Within the context of patient-centered care, AL may also interfere with the ability to communicate and derive therapeutic alliance and empathy from primary healthcare providers [61, 62]. Recent work has shed light on how levels of patient assertiveness in the doctor-patient relationship may negate the influence of AL on the doctor-patient relationship [63, 64]. Although these interactions have not been tested in HIV-infected persons with AL, patients exemplifying lower assertiveness do demonstrate a higher propensity for risky health behaviors [65], which begs the question of whether assertiveness can mediate the negative psychosocial outcomes of HIV-infected individuals with AL.

Only recently has AL been examined within the context HIV disease, thus large population studies of its prevalence remain elusive. However, two recent studies found between 25 and 40 % of HIV patients surveyed met the cut-off criteria for AL as measured by the Toronto Alexithymia Scale [39, 66]. The reason for this prevalence is unknown; however the co-incidence of mild neurocognitive impairment with higher observed levels of trait might suggest a neurobiological underpinning [38, 67, 68]. Subclinical and clinical markers of HIV and cardiovascular disease severity, including HIV-1 viral RNA, elevated urinary norepinephrine, and altered activity of the anti-inflammatory chemokine MIP-1α, that blocks T cell infection of HIV, have been associated with higher levels of trait AL [39, 66, 69, 70]. Although prior studies have shown a correlation between psychological distress and HIV-1 viral loads in alexithymic individuals with versus without HIV less is known about the effect on interpersonal relationships, particularly with primary care providers, and how it might relate to adherence behavior and HIV disease severity. The present study utilizes Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to simultaneously test (1) the relationship between trait AL and psychological distress, social support, and non-active patient involvement, (2) the relationship of psychological distress, social support, and non-active patient involvement on non-adherence to ART, (3) the relationship between non-adherence behavior and HIV disease severity, and (4) the mediating effect of patient assertiveness on the relationship of AL to distress, social support, and non-active patient involvement. Through these alternate psychosocial pathways, greater levels of trait AL are expected to be indirectly related to non-adherence and greater disease severity as a function lower social support, greater psychological distress and lower collaboration between doctor and patient. Furthermore, we predict greater patient assertiveness will mediate the effect of trait AL on these measures of psychosocial function.

Methods

Participants

Four hundred and thirty-nine HIV positive adults (324 males) that completed a self-report measure of alexithymia at baseline were selected from a series of studies conducted between 1997 and 2002. Approximately 52 % of the sample was comprised of a longitudinal cohort of patients at the mid-range of illness (CD4 between 150 and 500) with no history of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) or category C symptoms [55]. Nearly 16 % of the sample were drawn for a study of asymptomatic patients with low CD4 counts (<50) [71]. Fifteen percent of the sample were drawn from a cohort study of long-term survivors [72]. Approximately 17 % of the sample comprised of non-progressors, i.e., an HIV+ diagnosis ≥8 years and CD4 count >500). Additional exclusion criteria included comorbidity with a life-threatening illness outside the realm of HIV-spectrum disease (e.g., cancer); HIV Dementia Scale score <10 or Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) <25 indicating dementia or gross cognitive impairment; and current alcohol or drug dependence. Demographic information is displayed in Table 1.

Measures

Alexithymia

The 26-item version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-26) is a valid and reliable self-report measure of alexithymia [73]. The scale requires respondents to use a 5-point Likert scale to indicate from complete disagreement to complete agreement with 26 self-descriptive statements about the management of feelings and emotions. Scores may range from 26 to 130 with higher ratings reflecting greater levels of alexithymia. Persons who score ≥74 on the TAS-26 meet the criteria for alexithymia [74]. Scores in the current study ranged from 36 to 110. The TAS-26 demonstrated modest reliability across the cohort α = .76.

Assertiveness

The Adult Self-Expression Scale [75] is a 48-question survey that measures self-expression based upon responses to 25 positively- worded and 23 negatively-worded items on a 5-point Likert scale. Factor analysis on items of the self-expression scale has revealed at least three distinct components of assertiveness [76]. Affirmation of Rights includes 12 items reflecting situations in which self-affirmative anxiety is present because personal views or opinions were punished or ignored. The 18 items selected for the Request Behavior subscale measures involvement in making one’s own requests or refusing those from others. The Self-initiated Behavior subscale consists of 7 items describing self-initiated expressions of opinions and annoyance with others. The scale demonstrated high reliability in the sample (α = .87).

Social Support

Perceived social support was measured using the ENRICHED Social Support Instrument (ESSI), a 7-item scale assessing various forms of support, i.e., perceived emotional support, instrumental support, appraisal support, and relationship status over the past month [77] that was modified for the cohort. The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale [78] provided a measure of the degree to which the patient perceives they are socially connected to others. The scale requires one to endorse 20 statements, describing their relationships with, and feelings towards others, based on how often (never, rarely, sometimes and often) they feel that way. Higher scores indicate greater social isolation. The ESSI and loneliness scale demonstrated satisfactory reliability in the sample, (α = .76) and (α = .89) respectively.

Distress

Three indicators were used to reflect cumulative psychological distress, i.e., perceived stress, anxiety and depression. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 14-item survey that assesses the degree, on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), to which life was appraised as stressful due to unpredictable, uncontrollable and overwhelming experiences over the past month [79]. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item scale used to assess depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Participants rated items on a scale from 0 to 3 to identify the frequency with which they experienced each symptom [80]. The 20-item State subscale from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [81], was used to assess current state anxiety levels. The PSS, BDI and STAI surveys have acceptable psychometric properties [79–81].

Doctor Patient Relationship

This 5-item scale was developed to assess the level of active involvement exhibited by an HIV + patient with their primary care physician. The scale takes into account collaboration within the doctor patient relationship as it pertains to medication and treatment, it is predictive of 12-month antiretroviral medication adherence and also associated with survival in AIDS patients. Higher scores are indicative of lower patient involvement. The scale showed modest reliability in the sample (α = .72).

Adherence Behavior

Prescribed medications and adherence were assessed through an interviewer-administered AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Adherence Measure [82]. The proportion of doses missed over the 3 days leading up to the intake (ACTG-PMD) was queried for patients on anti-retroviral therapy. Research suggests that in addition to the proportion of missed dosages the inclusion of other behavioral data related to adherence best predicts viral RNA replication [83]. For those reporting missing any doses over the past month we presented a list of 12 reasons (ACTG-12) why people may miss taking their medications (e.g. wanted to avoid side effects, felt depressed/overwhelmed, busy with other things) and asked patients to rate on a four-point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often) how often each reason applied to them. The ACTG has demonstrated sound psychometric properties in HIV samples [82].

HIV Disease Severity

Serum viral load (VL) was measured by determining the number of HIV-1 virions per milliliter (ml) of peripheral blood plasma using the Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor RT/PCR assay (version 1.5, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ). Lower limit of sensitivity of this assay was 400 copies of HIV-1 RNA/ml of plasma. T-lymphocyte CD4+ count (CD3+CD4+) was determined via whole-blood 4-color direct immunofluorescence using a XL-MCL flow cytometer (Beckman/Coulter, Miami, FL). The total lymphocyte count was determined using a MaxM electronic hematology analyzer (Beckman/Coulter).

Statistical Analysis

We used a standard data screening and transformation of data using full information maximum likelihood under the assumption of data missing at random [84]. Traditional two-step approach to structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed, whereby a measurement model was tested while simultaneously examining the structure of paths [85]. Using the Mplus v.3.2 statistical program [86], confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) produced unbiased parameter estimates of relationships amongst variables in the theorized model, before and after accounting for socio-demographic covariates. Factor loadings and residual error variance were tested for significance at the .05 level. We proposed a model examining indirect and direct paths between alexithymia and both psychosocial and health-behavior and whether the effect of AL on these outcomes are mediated by assertiveness. Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized model including three pathways from AL to: (a) psychological distress, (b) Social Support, and (c) Active Patient Involvement; pathways from (d) Social Support and (e) Patient Involvement to psychological distress; pathways from (f) Distress, (g) Social Support and (h) Active Patient Involvement to Adherence Behavior; and a path from Adherence Behavior to (i) HIV Disease Severity.

Hypothesized Model. Model depicting hypothesized interrelationships among alexithymia social support, psychological distress, active patient involvement, adherence behavior and HIV disease severity. Open ovals represent latent variables. Open boxes represent observed variables. Hypothesized paths of significance are indicated by a solid black arrow. Light gray arrows depict the loadings for indicators of latent variables within the model

Two considerations were used to meet the criteria for an indicator to be retained in the final model. The observed variable first needed to load on one main latent factor that it was purported to measure and do so at a loading greater than .50. A reference indicator was selected for each latent factor in the model for the purpose of scaling. Model fit indices included Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) [87–89]. Acceptable measurement model fit was evaluated by CFI > .90; RMSEA < .06; and SRMR < .08 [90]. The χ2 fit statistic was not used to evaluate the path model because of inflation issues linked to large sample sizes (e.g., >200) [88, 91]. The proportion of variability explained (R 2) by each latent and observed variable in the model was assessed before entering covariates, i.e., age (years); sex (0 = male; 1 = female); ethnicity (0 = Caucasian, 1 = ethnic minority); education (years completed); and income (dollars per year). The present study also tested mediation of patient assertiveness on the direct paths from AL to psychological distress, Social Support and Patient Involvement.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic information for the cohort is presented in Table 1. Approximately 70 % of the cohort was male and over 90 % identified themselves as racial/ethnic minorities. On average, participants were early middle-aged and reported an annual household income below the U.S. poverty line (U.S. Census, 2002). Nearly half the sample exhibited an undetectable HIV-1 viral load and approximately one-quarter tested positive for Hepatitis-C Virus (HCV). Based on conventional criteria for HIV disease staging (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1993), approximately 19 % of the sample had low CD4 (<200), 64 % had a CD4 count between 200 and 500 and 17 % had a CD4 greater than or equal to 500. The mean rate adherence to full antiretroviral medication regimen in the days leading up to examination was high, i.e. 94.8 %.

Step 1: Measurement Model Validation

The factor structure of latent factors were operationalized as follows: (1) Social Support used ESSI and UCLA Loneliness scores; (2) psychological distress used PSS, BDI and TAS scores; (3) Non-adherence behavior was indexed by the ACTG-PMD and ACTG-12 subscales; (4) Disease Severity was indexed by HIV-1 viral load and CD4 T-lymphocyte count; (5) Assertiveness was indexed by the Affirmation, Request and Self-initiation subscales of the Adult Self Expression Scale. The measurement model showed adequate fit to proceed with path evaluation (CFI = .91, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07). Table 2 displays the statistically significant factor loadings (evinced by a correlation greater than .40) between each measured indicator and their respective latent factor.

Step 2: Model Evaluation

The test of the structure of the hypothesized model (see Fig. 2) showed excellent fit (CFI > .97, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05). Multiple paths within the proposed model were statistically significant: Greater alexithymia was linked to lower Social Support (β = −.50, z = −.13.02, p < .001), greater psychological distress (β = .27, z = 5.36, p = < .001), and non-active patient involvement (β = .13, z = 2.85, p = < .01). Social Support was not related to Non-adherence Behavior, (β = .12, z = .98, p > .05), but had an inverse relationship to psychological distress, (β = −.55, z = −10.94, p < .001). Less active involvement in the doctor-patient relationship was associated with Non-adherence Behavior, (β = .14, z = 2.72, p < .05), but shared no association with psychological distress, (β = .01, z = .29, p > .05). Greater PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS was associated with non-adherence, (β = .28, z = 4.51, p < .05). There was also a direct positive path from poorer adherence behaviors to greater disease severity, (β = .50, z = 4.65, p < .01). The model exhibited adequate fit accounting for significant paths between the covariates of interest with observed variables and latent factors (CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05).

Trimmed Hypothesized Model. Model depicting paths among alexithymia, social support, psychological distress, active patient involvement, adherence behavior and HIV disease severity. Open ovals represent latent variables. Open boxes represent observed variables. Path coefficients are standardized β weights. Positive path coefficients indicate a positive relationship, whereas negative path coefficients reflect inverse relationship. Solid arrows depict statistically significant associations and dashed arrows depict non-significant path coefficients (***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05)

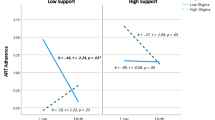

The model depicted in Fig. 3 demonstrates acceptable fit to the data (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05) and depicts mediation by the assertiveness factor. Specifically, the final model revealed that upon addition of a negative path from AL to Assertiveness, (β = −.66, z = −16.00, p < .001), and positive path from Assertiveness to Social Support, (β = .51, z = 6.17, p < .001) the significance of the path from AL to Social Support fell to marginally significant (β = −.16, z = 2.10, p = .05). Additionally, the path created from Assertiveness to non-active patient involvement (β = −.26, z = −3.09, p < .01), decreased significance of the direct path from trait AL to non-active involvement (β = −.04, z = −.51, p > .05). The path from Assertiveness to psychological distress was non-significant, (β = .01, z = .12, p > .05), and did not change the magnitude of association between AL and psychological distress, (β = .28, z = 4.33, p < .001). Overall, the trimmed model provides evidence that in HIV greater levels of Assertiveness may mediate the negative interpersonal impact of AL on interpersonal relationships with primary care providers and persons within the broader social support network. Finally, in line with our hypothesis, the sum of all indirect paths from AL to HIV disease severity was significant (β = .01, z = 2.60, p < .01).

Mediation Model. The mediation model is depicted above. Open ovals represent latent variables. Open boxes represent observed variables. Positive path coefficients indicate a positive relationship, whereas negative path coefficients reflect inverse relationship. The model shows assertiveness mediates the relationship between alexithymia and both social support and active patient involvement. The direct path from alexithymia to psychological distress was not mediated and is not shown. Non-significant paths not associated with the mediation test are not shown. Solid arrows depict statistically significant associations and dashed arrows depict non-significant path coefficients (***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05)

Table 3 presents the unique variance in each latent construct found within the model before and after accounting for significant sociodemographic predictors, i.e., control variables. Accounting for these covariates explained an additional 2 % of the variance in Social Support, 1 % of the variance in psychological distress, 10 % of the variance in Assertiveness, 2 % of the variance in Non-adherence Behavior and 30 % of the variance in HIV Disease Severity.

Discussion

The present study used an SEM approach to test the hypothesis that higher levels of trait alexithymia is associated with greater non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV disease severity via lower psychosocial functioning. Our model showed that higher AL was directly associated with lower social support, greater psychological distress, and more non-active patient involvement. The path between trait AL and both social support and non-active patient involvement was statistically mediated by assertiveness, although psychological distress was not, suggesting self-expression plays a unique role in buffering the negative interpersonal consequence of trait AL. Several demographic variables were also controlled for in the final model. Lower income level was associated with greater distress, lower support, and lower assertiveness, whereas lower education correlated with greater non-adherence behavior and HIV disease severity. These findings correspond with the role of sociodemographic factors on adjustment to HIV disease proposed by others [92–94]. Altogether, the model uncovered a substantial indirect effect for trait AL on HIV disease severity, accounting for 49 % of the variance in viral load and CD4 T-lymphocyte counts. What follows is an explanation of the significance of these paths, within the context of HIV health and health behaviors.

The inverse association between AL and social support suggests that difficulty identifying and describing feelings can undermine perceptions of interconnectedness with others and lower overall perceptions of social support. Parenthetical descriptions of persons with AL depict cynical, bitter, and shy characteristics which may hamper the ability to establish meaningful relationships and trust with others [95, 96]. Mediation of the paths from AL to social support and non-active patient involvement, by assertiveness, underscores the importance of emotional expression and recognition towards the communication of needs and maintenance of a supportive social network [97]. These findings are also replicated within a virtual social network. Since the beginning of the epidemic, patients have sought social support via online forums due to the stigmatizing nature of HIV/AIDS disease [98, 99]. Assertive online behavior, indexed by greater frequency and depth of self-expression during online posts, has been linked to greater derivation of instrumental support from the online experience [99], a finding which has also been replicated in non-HIV related discussion forums [100]. Contrary to previous reports [1, 26], social support was not related to medication adherence. This is likely because the social support factor consisted of indictors emphasizing degree of interconnectedness and quality of relationships, whereas practical support is most consistently related to medication adherence [101]. Although social support was not directly linked to medication adherence an indirect path was found via psychological distress, thus replicating prior models proposed from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [25, 102].

In our model, distress was associated with lower antiretroviral medication adherence behavior. HIV literature pertaining to the independent effects of depression, anxiety, stress and traumatic life experiences on non-adherence to antiretroviral medication regimen is rather equivocal with the strongest associations found with major depression and lowest with general anxiety [103–105]. Studies show mental health treatment may contribute to greater cART adherence from the enhanced ability to maintain a complex medication regimen or increased contact with physicians due to mental health referral [103, 106, 107]. Because our cross-sectional measure of 3-day adherence may not be the optimal index of adherence behavior in HIV patients [108–110], our factor also included an index of reasons why people missed medication doses, the most frequent being “simply forgot”. It is possible that some of the problem-solving and cognitive-behavioral factors underlying adherence may also underlie the presentation of depressive symptoms in HIV + persons [1, 111]. In the model, greater trait AL had an indirect effect on non-adherence behavior via greater Psychological Distress. Although causality cannot be inferred by the cross-sectional design of this study, the path from AL to Psychological Distress is supported by literature showing functional distinction amongst AL, depression, and anxiety; the overlap of different dimensions of AL with symptoms of depression and anxiety; and longitudinal studies demonstrating stability of the AL trait [56, 112–116]. Alternatively, AL may develop as a defensive coping style or response to a traumatic event [117–120]. Nevertheless, a lone study showing the independence of AL from a Type C coping construct in HIV positive individuals [69], also supports the functional distinction of trait AL in our model.

Our model also suggests an indirect pathway from AL to non-adherence behaviors and HIV disease severity as a function of active patient involvement. Lower ratings of collaboration between the doctor and patient have previously been linked to a greater percentage of prescribed dosages missed by HIV patients [121, 122]. Specifically, establishing trust with healthcare providers and demonstrating the ability to communicate and initiate discussions regarding standards and strategies of care have been identified as salient predictors of adherence to anti-retroviral therapy [122, 123]. The intermediary effect of assertiveness on the path between AL and active patient involvement corresponds with non-HIV findings of cold, distant and non-assertive behavior leadings to interpersonal dysfunction in persons with higher trait AL [124, 125]. Thus, despite stability of the AL trait, interpersonal behavior may be amendable to change through focus on self-expressive behaviors such as initiating requests to health practitioners. Training patients in assertiveness not only improves the quality of doctor-patient relationship but also improves compliance and disease outcomes [126, 127]. Moreover, physicians may also benefit from emotional awareness and sensitivity training in order to better support collaborative healthcare relationships with the patient [128].

It is commonly held by psychotherapists that AL is a difficult problem to treat, particularly in patients with psychosomatic complaints [129, 130]. Recently, it has been suggested that the AL construct be re-conceptualized as a form of affective agnosia, wherein the difficulty observed identifying and communicating feelings may actually reflect paucity in the mental representation of emotions by virtue of a deficit in cognitive awareness [131]. Neuroimaging studies have uncovered paucity in cortical activations associated with the decoding of affect in persons with higher levels of AL [132–135]. Because altered activity and volumetric reductions within brain structures associated with AL, such as anterior cingulate, are also observed in persons living with HIV [136] including those demonstrating an emotion recognition impairment [137] and patients with high negative affect [138], therapies that target cognitive and emotional functioning will are needed. Some of the more promising treatment options that may promote the mental representation of affect for persons with HIV may include Mentalization-based therapy [139] and Emotion Focused Therapy [140]. In addition, empirical evidence suggests that higher pre-treatment levels of AL do not have a negative impact on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) outcomes [141, 142]. Thus, for HIV patients with AL, CBT may still be an attractive option to decrease non-adherence and psychological distress, while increasing levels of social support [143–146].

The intermediary effect of patient assertiveness on AL-associated outcomes implies that both representation and expression of affect are both important elements of psychosocial functioning and HIV disease management. Expressive behavior, whether verbal or written, is thought to facilitate the development of affective taxonomy in persons with AL [147–149]. This may also have implications for chronic disease management as our lab and others have found expressive writing and emotional disclosure to predict immune function and long-term survival in patients living with HIV/AIDS [150–152], whereas alexithymia or inexpressiveness, i.e., Type C coping has been linked to immune dysfunction and HIV disease progression [69, 153]. Thus, training in expressive writing and assertiveness, in conjunction with cognitive behavioral therapy, may be provide the interpersonal skills needed to ensure psychosocial functioning and health in both HIV [154, 155] and non-HIV populations [37, 156–158].

Limitations

One major limitation of the current study is that the self-report measures of non-adherence behavior may be less accurate than structured interview or electronic monitoring [108]. Another limitation is that the data was collected between 1997 and 2002 from a sample of patients characterized as being healthy survivors living with HIV, with no prior AIDS diagnosis. This sample can be thought of as considered atypical based upon their mean rate adherence to antiretroviral medication regimen during that period, i.e. 94.8 %. Extrapolation of our findings may be limited by the predominately (75 %) male representation. Due to the stringent exclusion criteria for comorbid systemic medical and psychiatric diagnoses, our findings may not generalize to HIV patients at risk of or receiving treatment for mental health diagnoses. In terms of study design, the conceptual model and analysis utilized cross-sectional data and thus limiting any inference of causality amongst the directional effects portrayed. Extensions of this work will need to incorporate longitudinal design to better assess AL-dependent change in psychosocial function, medication adherence and HIV disease progression. Future examination of the extent to which AL interacts with HIV-associated neurocognitive dysfunction to predict medication adherence would also build on this and extant HIV literature [66, 67, 159, 160].

Conclusions

These findings add to the growing body of literature demonstrating positive and negative psychosocial and health outcomes associated with dispositional traits in HIV positive individuals [7, 161–164]. It is important to acknowledge that assertiveness and difficulty identifying and describing feelings entails two-way communication between the patient and individuals outside and within the extended medical and social support network. Thus, allied healthcare professionals, i.e., psychotherapists, case workers, nurses as well as physicians, may benefit from emotional awareness, cultural sensitivity, and interpersonal communication training in order to better promote medication adherence and psychosocial function in persons living with HIV disease.

References

Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):124.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–3.

Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Supplement 2):S171–6.

Ironson G, Lucette A, McIntosh R. Doctor-patient relationship: active patient involvement (DPR: API) is related to long survival status and predicts adherence change in HIV. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6(2):1–5.

Chida Y, Vedhara K. Adverse psychosocial factors predict poorer prognosis in HIV disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective investigations. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(4):434–45.

Ironson GH. Hayward Hs. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):546.

Turner BJ, Laine C, Cosler L, Hauck WW. Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in hiv-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):248–57.

Motivala SJ, Hurwitz BE, Llabre MM, Klimas NG, Fletcher MA, Antoni MH, et al. Psychological distress is associated with decreased memory helper T-cell and B-cell counts in pre-AIDS HIV seropositive men and women but only in those with low viral load. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):627–35.

Greeson JM, Hurwitz BE, Llabre MM, Schneiderman N, Penedo FJ, Klimas NG. Psychological distress, killer lymphocytes and disease severity in HIV/AIDS. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(6):901–11.

McIntosh RC, Hurwitz BE, Antoni M, Gonzalez A, Seay J, Schneiderman N. The ABCs of trait anger, psychological distress, and disease severity in HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2014;3:1–14.

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. JAIDS. 2011;58(2):181–7.

Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB. Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living (NFHL) study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2010;53(2):266.

Carrico AW, Riley ED, Johnson MO, Charlebois ED, Neilands TB, Remien RH, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for HIV disease progression: the role of inconsistent patterns of anti-retroviral therapy utilization. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2011;56(2):146.

Sledjeski EM, Delahanty DL, Bogart LM. Incidence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression on adherence to HAART and CD4 + counts in people living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19(11):728–36.

Schönnesson LN, Williams ML, Ross MW, Bratt G, Keel B. Factors associated with suboptimal antiretroviral therapy adherence to dose, schedule, and dietary instructions. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):175–83.

Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253–61.

Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, Milau V, Carrera G. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294–6.

Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Hendriksen E. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress and death anxiety in persons with HIV and medication adherence difficulties. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17(12):657–64.

Leserman J, Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fordiani JM, Balbin E. Stressful life events and adherence in HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(5):403–11.

Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, Whetten K, Leserman J, Thielman NM, et al. Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9):920–6.

Bottonari KA, Safren SA, McQuaid JR, Hsiao C-B, Roberts JE. A longitudinal investigation of the impact of life stress on HIV treatment adherence. J Behav Med. 2010;33(6):486–95.

Campos LN, Guimarães MDC, Remien RH. Anxiety and depression symptoms as risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):289–99.

Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, Trotta MP, Ravasio L, De Longis P, et al. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. JAIDS. 2001;28(5):445–9.

Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Durán RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G, et al. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychol. 2004;23(4):413.

Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, et al. Social support, substance use, and denial in relationship to antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17(5):245–52.

Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Tavakoli A, Phillips KD, Murdaugh C, Jackson K, et al. Social support, coping, and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with depression living in rural areas of the southeastern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(9):667–80.

Ingram KM, Jones DA, Fass RJ, Neidig JL, Song YS. Social support and unsupportive social interactions: their association with depression among people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 1999;11(3):313–29.

Song YS, Ingram KM. Unsupportive social interactions, availability of social support, and coping: their relationship to mood disturbance among African Americans living with HIV. J Soc Pers Relationsh. 2002;19(1):67–85.

Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–60.

Heckman CJ. Patient–clinician relationships and treatment system effects on HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(1):89–101.

Martini M, D’Elia S, Paoletti F, Cargnel A, Adriani B, Carosi G, et al. Adherence to HIV treatment: results from a 1-year follow-up study. HIV Med. 2002;3(1):62–4.

Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown M-A, Powell-Cope GM, Turner JG, Inouye J, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2000;14(4):189–97.

Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1096–103.

Roberts KJ. Physician-patient relationships, patient satisfaction, and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected adults attending a public health clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002;16(1):43–50.

Johnson MO, Chesney MA, Goldstein RB, Remien RH, Catz S, Gore-Felton C, et al. Positive provider interactions, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence to antiretroviral medications among HIV-infected adults: a mediation model. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(4):258–68.

J-fO Agbu. Management of negative self-image with rational emotive and behavioural therapy and assertiveness training. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2014;16(1):57–68.

McIntosh RC, Ironson G, Antoni M, Kumar M, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Alexithymia is linked to neurocognitive, psychological, neuroendocrine, and immune dysfunction in persons living with HIV. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:165–75.

Parruti G, Vadini F, Sozio F, Mazzott E, Ursini T, Polill E, et al. Psychological factors, including alexithymia, in the prediction of cardiovascular risk in HIV infected patients: results of a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54555.

Landstra J, Ciarrochi J, Deane FP, Hillman RJ. Identifying and describing feelings and psychological flexibility predict mental health in men with HIV. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):844–57.

Masiello A, De Guglielmo C, Giglio S, Acone N. Beyond depression: assessing personality disorders, alexithymia and socio-emotional alienation in patients with HIV infection. Le Infez Med. 2014;22(3):193–9.

Sozio F, Vadini F, Ursini T, Mazzotta E, Polilli E, Placido G, et al. Alexithymia as a major cardiovascular risk factor in HIV-infected patients. Infection. 2011;39:S37.

Sifneos PE. The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22(2–6):255–62.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. J Pers Assess. 2007;89(3):230–46.

Jørgensen MM, Zachariae R, Skytthe A, Kyvik K. Genetic and environmental factors in alexithymia: a population-based study of 8,785 Danish twin pairs. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):369–75.

Picardi A, Fagnani C, Gigantesco A, Toccaceli V, Lega I, Stazi MA. Genetic influences on alexithymia and their relationship with depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(4):256–63.

Bermond B, Vorst HC, Moormann PP. Cognitive neuropsychology of alexithymia: implications for personality typology. Cognit Neuropsychiatry. 2006;11(3):332–60.

Wingbermühle E, Theunissen H, Verhoeven W, Kessels RP, Egger JI. The neurocognition of alexithymia: evidence from neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2012;24(2):67–80.

Salminen JK, Saarijärvi S, Äärelä E, Toikka T, Kauhanen J. Prevalence of alexithymia and its association with sociodemographic variables in the general population of Finland. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(1):75–82.

Kokkonen P, Karvonen JT, Veijola J, Läksy K, Jokelainen J, Järvelin M-R, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of alexithymia in a population sample of young adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(6):471–6.

Papciak AS, Feuerstein M, Spiegel JA. Stress reactivity in alexithymia: decoupling of physiological and cognitive responses. J Hum Stress. 1985;11(3):135–42.

Martin JB, Pihl R. The stress-alexithymia hypothesis: theoretical and empirical considerations. Psychother Psychosom. 1985;43(4):169–76.

Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Tanskanen A, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Depression is strongly associated with alexithymia in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(1):99–104.

Luminet O, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. An evaluation of the absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in patients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70(5):254–60.

Marchesi C, Brusamonti E, Maggini C. Are alexithymia, depression, and anxiety distinct constructs in affective disorders? J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(1):43–9.

Posse M, Hällström T, Backenroth-Ohsako G. Alexithymia, social support, psycho-social stress and mental health in a female population. Nord J Psychiatry. 2002;56(5):329–34.

Bratis D, Tselebis A, Sikaras C, Moulou A, Giotakis K, Zoumakis E, et al. Alexithymia and its association with burnout, depression and family support among Greek nursing staff. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:72.

Lumley MA, Ovies T, Stettner L, Wehmer F, Lakey B. Alexithymia, social support and health problems. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41(6):519–30.

Kojima M, Hayano J, Tokudome S, Suzuki S, Ibuki K, Tomizawa H, et al. Independent associations of alexithymia and social support with depression in hemodialysis patients. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(4):349–56.

Graugaard PK, Holgersen K, Finset A. Communicating with alexithymic and non-alexithymic patients: an experimental study of the effect of psychosocial communication and empathy on patient satisfaction. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(2):92–100.

Finset A, Graugaard PK, Holgersen K. Salivary cortisol response after a medical interview: the impact of physician communication behaviour, depressed affect and alexithymia. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(2):115–24.

Finset A. Emotional intelligence, alexithymia, and the doctor-patient relationship. Somatization and psychosomatic symptoms. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 91–8.

Vanheule S, Vandenbergen J, Verhaeghe P, Desmet M. Interpersonal problems in alexithymia: a study in three primary care groups. Psychol Psychother. 2010;83(4):351–62.

Crowell T. Seropositive individuals willingness to communicate, self-efficacy, and assertiveness prior to HIV infection. J Health Commun. 2004;9(5):395–424.

McIntosh RC, Ironson G, Antoni M, Kumar M, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Alexithymia is linked to neurocognitive, psychological, neuroendocrine, and immune dysfunction in persons living with HIV. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;36:165–75.

Bogdanova Y, Díaz-Santos M, Cronin-Golomb A. Neurocognitive correlates of alexithymia in asymptomatic individuals with HIV. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(5):1295–304.

McIntosh RC, Rosselli M, Uddin LQ, Antoni M. Neuropathological sequelae of human immunodeficiency virus and apathy: a review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:147–64.

Temoshok LR, Waldstein SR, Wald RL, Garzino-Demo A, Synowski SJ, Sun L, et al. Type C coping, alexithymia, and heart rate reactivity are associated independently and differentially with specific immune mechanisms linked to HIV progression. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(5):781–92.

Lumley MA, Tomakowsky J, Torosian T. The relationship of alexithymia to subjective and biomedical measures of disease. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(5):497–502.

Ironson G, Balbin E, Solomon G, Fahey J, Klimas N, Schneiderman N, et al. Relative preservation of natural killer cell cytotoxicity and number in healthy AIDS patients with low CD4 cell counts. AIDS. 2001;15(16):2065–73.

Gail Ironson M, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, O’Cleirigh C, George A, Kumar M, et al. The Ironson-Woods Spirituality/Religiousness Index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress, and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):34–48.

Taylor GJ, Ryan D, Bagby RM. Toward the development of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychother Psychosom. 1985;44(4):191–9.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Measurement of alexithymia: recommendations for clinical practice and future research. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1988;11:351–66.

Gay ML, Hollandsworth JG, Galassi JP. An assertiveness inventory for adults. J Couns Psychol. 1975;22(4):340.

Lafromboise TD. The factorial validity of the adult selfexpression scale with American Indians. Educ Psychol Meas. 1983;43(2):547–55.

Mitchell PH, Powell L, Blumenthal J, Norten J, Ironson G, Pitula CR, et al. A short social support measure for patients recovering from myocardial infarction: the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2003;23(6):398–403.

Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472–80.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–71.

Spielberger CD. STAI manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Self-Eval Quest. 1970:1–24.

Chesney MA, Ickovics J, Chambers D, Gifford A, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS care. 2000;12(3):255–66.

Reynolds NR, Sun J, Nagaraja HN, Gifford AL, Wu AW, Chesney MA. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: a cross-protocol analysis. JAIDS. 2007;46(4):402–9.

Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Model. 2001;8(3):430–57.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus. Statistical analysis with latent variables Version. 2007;3.

Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238.

Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Lisrel 8: Structured equation modeling with the Simplis command language: Scientific Software International; 1993.

Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res. 1990;25(2):173–80.

Lt Hu. Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structl Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Articles. 2008:2.

Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Rustad CA, Zhang W, et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. JAIDS. 2008;47(4):500–5.

McMahon J, Wanke C, Terrin N, Skinner S, Knox T. Poverty, hunger, education, and residential status impact survival in HIV. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1503–11.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T. Stress and poverty predictors of treatment adherence among people with low-literacy living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):810–6.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. New trends in alexithymia research. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(2):68–77.

Nicolò G, Semerari A, Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G, Conti L, D’Angerio S, et al. Alexithymia in personality disorders: correlations with symptoms and interpersonal functioning. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(1):37–42.

Meganck R, Vanheule S, Inslegers R, Desmet M. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems: a study of natural language use. Personal Individ Differ. 2009;47(8):990–5.

Coursaris CK, Liu M. An analysis of social support exchanges in online HIV/AIDS self-help groups. Comput Hum Behav. 2009;25(4):911–8.

Mo PK, Coulson NS. Empowering processes in online support groups among people living with HIV/AIDS: a comparative analysis of ‘lurkers’ and ‘posters’. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(5):1183–93.

Huffaker D. Dimensions of leadership and social influence in online communities. Human Commun Res. 2010;36(4):593–617.

Scheurer D, Choudhry N, Swanton KA, Matlin O, Shrank W. Association between different types of social support and medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(12):e461–7.

Simoni JM, Frick PA, Huang B. A longitudinal evaluation of a social support model of medication adherence among HIV-positive men and women on antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):74.

Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The effect of mental illness, substance use, and treatment for depression on the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(3):233–43.

Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Remien RH, Rosen MI, Simoni J, Bangsberg DR, et al. A closer look at depression and its relationship to HIV antiretroviral adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):352–60.

Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2119–43.

Himelhoch S, Brown CH, Walkup J, Chander G, Korthius PT, Afful J, et al. HIV patients with psychiatric disorders are less likely to discontinue HAART. AIDS (London, England). 2009;23(13):1735.

Cruess DG, Kalichman SC, Amaral C, Swetzes C, Cherry C, Kalichman MO. Benefits of adherence to psychotropic medications on depressive symptoms and antiretroviral medication adherence among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(2):189–97.

Llabre MM, Weaver KE, Durán RE, Antoni MH, McPherson-Baker S, Schneiderman N. A measurement model of medication adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and its relation to viral load in HIV-positive adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(10):701–11.

Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):86–94.

Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, et al. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: life-steps and medication monitoring. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(10):1151–62.

Hintikka J, Honkalampi K, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Are alexithymia and depression distinct or overlapping constructs?: a study in a general population. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):234–9.

Saarijärvi S, Salminen J, Toikka T. Alexithymia and depression: a 1-year follow-up study in outpatients with major depression. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(6):729–33.

Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Saarinen P, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Is alexithymia a permanent feature in depressed patients? Results from a 6-month follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:303–8.

Honkalampi K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Tanskanen A, Hintikka J, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Why do alexithymic features appear to be stable? Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:247–53.

Luminet O, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. An evaluation of the absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in patients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;2001(70):254–60.

Parker JD, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Alexithymia: relationship with ego defense and coping styles. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):91–8.

Wise TN, Mann LS, Epstein S. Ego defensive styles and alexithymia: a discriminant validation study. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;56(3):141–5.

Helmes E, McNeill PD, Holden RR, Jackson C. The construct of alexithymia: associations with defense mechanisms. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(3):318–31.

Besharat MA. Relationship of alexithymia with coping styles and interpersonal problems. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:614–8.

van Servellen G, Lombardi E. Supportive relationships and medication adherence in HIV-infected, low-income Latinos. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27(8):1023–39.

Molassiotis A, Morris K, Trueman I. The importance of the patient–clinician relationship in adherence to antiretroviral medication. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007;13(6):370–6.

Brion J. The patient–provider relationship as experienced by a diverse sample of highly adherent HIV-infected people. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;25:123–34.

Vanheule S, Desmet M, Meganck R, Bogaerts S. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(1):109–17.

Grabe H, Spitzer C, Freyberger H. Alexithymia and the temperament and character model of personality. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70(5):261–7.

Beisecker AE. Patient power in doctor-patient communication: what do we know? Health Communication. 1990;2(2):105–22.

Ferguson WJ, Candib LM. Culture, language, and the doctor-patient relationship. FMCH Publ Present. 2002;61.

Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1):21–34.

Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS. Effect of alexithymia on the process and outcome of psychotherapy: a programmatic review. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(1):43–8.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Psychoanalysis and empirical research: the example of alexithymia. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2013;61(1):99–133.

Lane RD, Weihs KL, Herring A, Hishaw A, Smith R. Affective agnosia: expansion of the alexithymia construct and a new opportunity to integrate and extend freud’s legacy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:594–611.

Hesse C, Floyd K, Rauscher EA, Frye-Cox NE, Hegarty JP, Peng H. Alexithymia and impairment of decoding positive affect: an fMRI study. J Commun. 2013;63(4):786–806.

Moriguchi Y, Komaki G. Neuroimaging studies of alexithymia: physical, affective, and social perspectives. BioPsychoSoc Med. 2013;7(1):8.

Kano M, Fukudo S. The alexithymic brain: the neural pathways linking alexithymia to physical disorders. Biopsychosoc Med. 2013;7(1):1.

Heinzel A, Schäfer R, Müller H-W, Schieffer A, Ingenhag A, Eickhoff SB, et al. Increased activation of the supragenual anterior cingulate cortex during visual emotional processing in male subjects with high degrees of alexithymia: an event-related fMRI study. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(6):363–70.

Kallianpur KJ, Kirk GR, Sailasuta N, Valcour V, Shiramizu B, Nakamoto BK, et al. Regional cortical thinning associated with detectable levels of HIV DNA. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(9):2065–75.

Clark US, Walker KA, Cohen RA, Devlin KN, Folkers AM, Pina MJ, et al. Facial emotion recognition impairments are associated with brain volume abnormalities in individuals with HIV. Neuropsychologia. 2015;70:263–71.

Kremer H, Lutz FP, McIntosh RC, Dévieux JG, Ironson G. Interhemispheric asymmetries and theta activity in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex as EEG signature of HIV-related depression gender matters. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2015. doi:10.1177/1550059414563306.

Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Greenberg LS. Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings: Am Psychol Assoc. 2002.

Rufer M, Albrecht R, Zaum J, Schnyder U, Mueller-Pfeiffer C, Hand I, et al. Impact of alexithymia on treatment outcome: a naturalistic study of short-term cognitive-behavioral group therapy for panic disorder. Psychopathology. 2010;43(3):170–9.

Rufer M, Hand I, Braatz A, Alsleben H, Fricke S, Peter H. A prospective study of alexithymia in obsessive-compulsive patients treated with multimodal cognitive-behavioral therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(2):101–6.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):1.

Antoni MH, Baggett L, Ironson G, LaPerriere A, August S, Klimas N, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention buffers distress responses and immunologic changes following notification of HIV-1 seropositivity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(6):906.

Lutgendorf SK, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Starr K, Costello N, Zuckerman M, et al. Changes in cognitive coping skills and social support during cognitive behavioral stress management intervention and distress outcomes in symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive gay men. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(2):204–14.

Cruess S, Antoni MH, Hayes A, Penedo F, Ironson G, Fletcher MA, et al. Changes in mood and depressive symptoms and related change processes during cognitive–behavioral stress management in HIV-Infected Men. Cognit Ther Res. 2002;26(3):373–92.

Sundararajan L, Schubert LK. Verbal expressions of self and emotions A taxonomy with implications for Alexithymia and. Conscious Emot. 2005;1:243.

Smyth J, True N, Souto J. Effects of writing about traumatic experiences: the necessity for narrative structuring. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2001;20(2):161–72.

Sundararajan L, Kim C, Reynolds M, Brewin CR. Language, emotion, and health: a semiotic perspective on the writing cure. In: Hamel SC, editor. Semiotics: Theory and applications. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2011. p. 65–97.

O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Written emotional disclosure and processing of trauma are associated with protected health status and immunity in people living with HIV/AIDS. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):81–4.

Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272–5.

O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Antoni M, Fletcher MA, McGuffey L, Balbin E, et al. Emotional expression and depth processing of trauma and their relation to long-term survival in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(3):225–35.

Solano L, Costa M, Temoshok L, Salvati S, Coda R, Aiuti F, et al. An emotionally inexpressive (Type C) coping style influences HIV disease progression at six and twelve month follow-ups. Psychol Health. 2002;17(5):641–55.

Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Klimas N, Maher K, Cruess S, Kumar M, et al. Stress management and immune system reconstitution in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men over time: Effects on transitional naïve T cells (CD4 + CD45RA + CD29 +). Am J Psychiatry. 2014.

Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, McQuaid JR, Patterson TL. Drug assertiveness and sexual risk-taking behavior in a sample of HIV-positive, methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41(3):265–72.

Lee TY, Chang SC, Chu H, Yang CY, Ou KL, Chung MH, et al. The effects of assertiveness training in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, single-blind, controlled study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(11):2549–59.

Hijazi AM, Tavakoli S, Slavin-Spenny OM, Lumley MA. Targeting interventions: moderators of the effects of expressive writing and assertiveness training on the adjustment of international university students. Int J Adv Couns. 2011;33(2):101–12.

Gidron Y. Assertiveness training. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 135–6.

Panos SE, Del Re A, Thames AD, Arentsen TJ, Patel SM, Castellon SA, et al. The impact of neurobehavioral features on medication adherence in HIV: Evidence from longitudinal models. AIDS Care. 2013(ahead-of-print):1–8.

Patton DE, Woods SP, Franklin D Jr, Cattie JE, Heaton RK, Collier AC, et al. Relationship of medication management test-revised (MMT-R) performance to neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral adherence in adults with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2286–96.

Ironson G, Balbin E, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA, O’Cleirigh C, Laurenceau J, et al. Dispositional optimism and the mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(2):86–97.

O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Weiss A, Costa PT Jr. Conscientiousness predicts disease progression (CD4 number and viral load) in people living with HIV. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):473.

Penedo FJ, Gonzalez JS, Dahn JR, Antoni M, Malow R, Costa P, et al. Personality, quality of life and HAART adherence among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(3):271–8.

Ironson GH, O’Cleirigh C, Weiss A, Schneiderman N, Costa PT. Personality and HIV disease progression: role of NEO-PI-R openness, extraversion, and profiles of engagement. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(2):245–53.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was made possible by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) fellowship support T32-MH018917, research grant support R01-MH095624and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NAID) center Grant support P30-NIAID1073961.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McIntosh, R.C., Ironson, G., Antoni, M. et al. Alexithymia, Assertiveness and Psychosocial Functioning in HIV: Implications for Medication Adherence and Disease Severity. AIDS Behav 20, 325–338 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1126-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1126-7