Abstract

Background

Physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour are the main risk factors for non-communicable diseases in all stages of life. However, there is a lack of reliable data regarding the recommended level of physical activity and its correlates related to physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour among school students in Iran. The aim of the present study was to report the prevalence and correlates of physical activity/inactivity and sedentary behaviour among Iranian high school adolescents.

Methods

The Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) was used for data collection. Related data comprising socio-demographics, health risk behaviour and protective factors were obtained from 1517 high school students. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between relevant independent variables (e.g. gender) and the dependent outcome variable (physical inactivity/sedentary behaviour).

Results

The prevalence of recommended physical activity by WHO was 27.8%, physical inactivity 72.2% and sedentary behaviour 71.4%. Being female, being overweight or obese, walking/cycling to or from school on 1–4 days, sitting 3 or more hours/day (sedentary behaviour), insufficient vegetable intake, being bullied and lack of parental support, peer support and parental connectivity (protective factors) were positively associated with physical inactivity. On the other hand, walking/cycling to or from school on 5–7 days and inadequate fruit intake were negatively associated with physical inactivity. Walking/cycling to or from school on 1–4 days, being physically inactive, inadequate fruit intake and being bullied were positively associated with sedentary behaviour.

Conclusion

The prevalence of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour was high in our studied sample. Interventions that address the issue of active school transport, sedentary behaviour, fruit and vegetable intake, family and peer support and bullying should be given more priority by the public health authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), non-communicable diseases (NCDs) will be responsible for the deaths of 52 million people globally by 2030. Developing countries suffer the highest burden of NCDs. For instance, in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) NCDs are the leading cause of death and each year 1.7 million people lose their lives (WHO 2011). Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and chronic respiratory ailments are known as NCDs or lifestyle-related diseases. By simple life-style changes many of the deaths from these diseases could be prevented. Physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, tobacco use and harmful alcohol drinking are related to high blood pressure, obesity, hyperlipidaemia and high blood glucose, which increase the risk of NCDs (Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014). Almost all of these risk factors are related to physical activity (PA) and diet, and these play an important role in preventing disease and maintaining health (Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health 2004).

Adolescence is a critical period in life and has an important role in the formation of behavioural and nutritional habits. Some studies have shown that behavioural risk factors associated with NCDs, such as lack of exercise, persist from adolescence into adulthood (Veltsista et al. 2010), while this period of life is the best time for adoption of physical activity (PA) behaviour (Paudel et al. 2014). According to WHO, the recommended global PA level for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years is at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous PA per day for maintaining healthy body weight, healthy musculoskeletal tissue and improving the cardiorespiratory system (Global recommendations on physical activity for health 2010). Additionally, physically active adolescents have more negative attitudes to tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption than their peers (Diet and physical activity: a public health priority 2004).

The adolescents’ PA patterns have changed and decreased due to time spent watching TV, and screen-based activities. According to the evidence, watching TV more than 2 h per day is correlated with reduced physical and psychosocial health (Tremblay et al. 2011). Physical activity levels lower than 60 min per day on at least 5 days per week are defined as physical inactivity and sitting 3 or more hours per day is defined as sedentary behaviour (Al Subhi et al. 2015, Guthold et al. 2010).

Physical inactivity is related to psychological complaints among males and females (Marques et al. 2015), and according to a review study, sedentary behaviour and having higher levels of screen time activities are associated with more attention problems and reduced psychological well-being (Suchert et al. 2015). Furthermore, studies have shown that physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour in adolescents are associated with factors such as age (Dumith et al. 2011), younger age (Trang et al. 2009), older age (Baharudin et al. 2014), gender (Teng et al. 2014), being female (Trang et al. 2009), socioeconomic status (Lord et al. 2015) and higher socioeconomic status (Muthuri et al. 2014). Body mass index (BMI) has also been identified as an important factor: In some studies, higher BMI was related to physical inactivity (Trang et al. 2009, Baharudin et al. 2014), and in others was related to sedentary behaviour (Prentice-Dunn and Prentice-Dunn 2012). Being bullied (Henriksen et al. 2016), inadequate fruit and vegetable intake (Pate et al. 1996), not attending physical education classes (Tassitano et al. 2010), smoking (de Winter et al. 2016), lack of breakfast (Baharudin et al. 2014) and lack of social and parental support for physical activity (Tate et al. 2015, Siceloff et al. 2014) have also been found to be associated with physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour.

According to a study comparing adolescents attending school (aged 13–15 years) in 34 countries, who participated at the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), only 23.8% of boys and 15.4% of girls met WHO recommendations for physical activity (Guthold et al. 2010). Another study among adolescents, aged 13–15 years in eight African countries, showed that only 14.2% of school children were active and met the WHO recommendation for PA, and among school students aged 13–17 years in ten EMRO countries, the overall prevalence of PA was 19% (Al Subhi et al. 2015). In the United States and among high school students in 2013, only 29% participated in PA at least 60 min per day (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2015).

According to a literature review and to the author’s knowledge, there are no studies in Iran that report the PA level in Iranian adolescents based on the WHO recommendation. Additionally, most Iranian studies reported only mixed results of PA levels such as the Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET), nutritional habits and screen time activities (Baygi et al. 2015, Kelishadi et al. 2007). According to the Caspian-III study in Iran, screen time activities, such as working with a computer, among Iranian adolescents is more than 4 h per day of which at least 3 h is watching TV (Baygi et al. 2015).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the prevalence of self-reported PA activity/inactivity level and sedentary behaviour and their correlates among a representative sample of high school students in the city of Tabriz, by using the reliable and valid, Persian version of the GSHS comprehensive questionnaire (Ziaei et al. 2014).

Methods

Study site and sampling

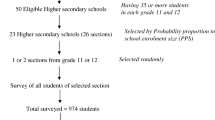

Tabriz, a city in the northwest of Iran with approximately 1,700,000 inhabitants, was the site of the present cross-sectional study. High school students (grades 9 to 11) included 62,714 students, of which 29,935 were female and 32,779 males during the 2013–14 academic years. A two-stage cluster sampling was used to select representative high schools and classes. At the first stage, high-schools were selected with probability proportional to the enrolment size, and at the second stage, classes were randomly selected, and all students in the selected classes were then eligible to participate in the study. Overall, 30 high-schools, including 16 girls’ and 14 boys’ high-schools, and 90 classes (grades 9 to 11) (Education System in Iran n.d.) were chosen to participate in the study. The full details of the methodology have been reported earlier (Ziaei et al. 2016, Ziaei et al. 2017, Ziaei et al. 2019).

Data collection

A reliable, valid and anonymous, self-administered, Persian version of the GSHS PA module questionnaire was used for data collection (Ziaei et al. 2014, Global School-based Student Health Survey Core Expanded Questionnaire 2009). The questions in this module measure physical activity, travel to and from school, participation in physical education classes and participation in sedentary leisure behaviour (Global School-based Student Health Survey Item Rationale 2009).

Data collection took place over approximately three months from 26 December 2013. GSHS is a global, youth behavioural surveillance system designed by WHO, with technical support from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Questionnaires were administered to students during an ordinary school day in selected schools and classes by Province Health Center staff, who, one week prior to the survey date, had attended a workshop on GSHS methodology. Answering time for questions was around 15 min.

Data processing and analysis

Measures

There are two dependent outcome variables: leisure time PA, which was defined as “any activity that increases your heart rate and makes you breathe hard, such as playing with friends, walking to school, running, walking fast, cycling, dancing and playing football”, and leisure time sedentary behaviour, which was assessed by asking about the time that students spend mostly sitting when they are not in school or doing homework. Leisure time PA was assessed by the question, “During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?”, and leisure time sedentary behaviour by, “How much time do you spend during a typical or usual day sitting and watching television, playing computer games, talking with friends, or engaging in other sitting activities?”. Detailed response options are presented in Table 1, and the prevalence of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Table 2.

Physical activity was defined as having at least 60 min’ moderate to vigorous physical activity per day on at least 5 days per week. Less than 5 days/week was defined as physical inactivity, with sedentary behaviour being defined as sitting 3 or more hours per day when not attending school or doing homework (Al Subhi et al. 2015, Guthold et al. 2010).

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (age and gender-specific) from self-reported body height and weight according to the formula (weight (kg)/height (m2)). Cut off points defining overweight and obesity were used. Students were considered overweight if their BMI was > +1SD from the median and obese if their BMI was > +2SD from the median for BMI for their age and sex (Cole et al. 2000). According to the CDC and WHO, insufficient fruit consumption was defined as eating fruit less than twice a day and inadequate vegetable consumption defined as less than 3 times a day (State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables 2013, Agudo 2004, Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations 2013).

Parental support and encouragement was addressed by the question, “During the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians support and encourage you?” and the alternative answers were, “always”, “most of the time”, “sometimes”, “rarely” and “never”. The answers were then classified into “Yes” or “No”. “Always” and “Most of the time” were classified as “Yes”, and “Sometimes”, “Rarely” and “Never” were classified as “No”.

Peer support in school was addressed by the question, “During the past 30 days, how often were most of the students in your school kind and helpful?” and parental or guardian connectedness by the question, “During the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians understand your problems and worries?”. The responses were classified in the same way as with the parental support question.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 24.0. Descriptive statistics were used to report frequency, percentages, mean and standard deviation. The two main outcome variables were self-reported physical activity and sedentary behaviour. A multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between relevant independent variables such as age, gender, grade, being bullied and the dependent outcome variables (physical activity and sedentary behaviour? Yes/No). Reporting of adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and unadjusted odds ratios (UAORs) was done after controlling for factors identified as significant in the bivariate analysis. AORs and UAORs with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. A p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant for other statistical tests.

Results

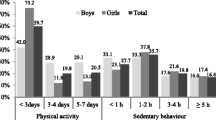

Prevalence of physical activity/inactivity and sedentary behaviour

The prevalence of recommended physical activity by WHO was 27.8%, physical inactivity 72.2% and sedentary behaviour 71.4%. There was a gender difference in physical activity, and girls were less physically active than boys. However, no gender difference was found in sedentary behaviour, although the boys had more sedentary behaviour than girls. Table 1 describes the sample characteristics and Table 2 the prevalence of physical activity/inactivity and sedentary behaviour.

Association with physical inactivity

Regression analysis has shown that being female, being overweight or obese, walking/cycling to or from school on 1–4 days, sitting 3 or more hours/d (sedentary behaviour), inadequate vegetable intake, being bullied, lack of parental and peer support and lack of parental connectivity (protective factors) were positively associated with physical inactivity. On the other hand, walking/cycling to or from school on 5–7 days, and inadequate fruit intake were negatively associated with physical inactivity (see Table 3).

Association with sedentary behaviour

Regression analysis has shown that walking/cycling to or from school on 1–4 days, being physically inactive, inadequate fruit intake and being bullied were positively associated with sedentary behaviour (see Table 4).

Discussion

The present study has shown a high prevalence of leisure time physical inactivity (72.2%) and sedentary behaviour (71.4%) as well as their correlates among high-school students in the city of Tabriz. Findings from other studies have shown a similar high prevalence of physical inactivity (Al Subhi et al. 2015, Guthold et al. 2010, Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2015, Baygi et al. 2015, Kelishadi et al. 2007).

Our findings show a gender difference with regard to PA levels, with girls having 48% higher odds of being physically inactive than boys. Such gender differences have also been reported earlier (Al Subhi et al. 2015, Kelishadi et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2016, Al-Hazzaa et al. 2011). This gender difference can be considered from different perspectives, such as social and environmental determinants of physical activity in terms of access to facilities, safe pavements and the possibility of engaging in physical activity in public places (Trang et al. 2009, Li et al. 2006). In Iran, females are prohibited from using bicycles in public places, thus resulting in girls being unable to cycle to and from school. The safety of pavements is another factor that encourage parents to provide school busses from or to schools. In general, social barriers for PA are more widespread for girls than boys.

The students with a higher BMI, i.e. overweight or obese, have 2.22 times higher odds of being physically inactive; our results being consistent with previous studies (Trang et al. 2009, Baharudin et al. 2014, de Onis et al. 2007, Pouliou et al. 2015). In Iran, research among school students has shown that there is a significant association between students’ PA level and their weight. Physically active students had a normal weight and were less engaged in sedentary behaviour (Moayeri et al. 2006). In some studies, higher BMI was associated with sedentary behaviour (Prentice-Dunn and Prentice-Dunn 2012, Collins et al. 2008) but not in the present study.

Students who reported walking/cycling to or from school on 5–7 days of week had 56% lower odds of being physically inactive than students who did not walk/cycle to or from school. On the other hand, students who walked/cycled to or from school on 1–4 days had 57% higher odds of being physically inactive. Research has shown that physically active school transport is the best way to promote PA levels and prevent overweight and obesity among school adolescents (Arango et al. 2011, Bere et al. 2011). In Iran, the main obstacles to physically active school transport were the use of cars (Moayeri et al. 2006), lack of safe pavements and some rules restricting females’ PA in public places. Our results showed that students walking/cycling 1–4 days from or to schools have 40% higher odds of sedentary behaviour.

Students with sedentary behaviour (sitting ≥3 h./day) have 53% higher odds of being physically inactive than students who sit less. According to an Iranian national study, Iranian school students had 4 h/day or more screen time activities (Baygi et al. 2015, (Kelishadi et al. 2007), i.e. in excess of the recommended time for screen time activities (not to exceed 2 h per day) by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (American Academy of Pediatrics 2001), and this long screen time leads to sedentary behaviour and negative health outcomes (Marques et al. 2015, Suchert et al. 2015). The association between sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity has been confirmed in various studies (Peltzer and Pengpid 2016, McVeigh and Meiring 2014) and our results showed that the physically inactive students had 85% higher odds of engaging in sedentary behaviour.

According to research, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake is associated with physical inactivity (Pate et al. 1996, (Winkvist et al. 2016). However, our results showed a negative association between physical inactivity and inadequate fruit intake. This means students reporting inadequate daily fruit intake (< 2 daily) showed 43% lower odds of being physically inactive, whilst students with an inadequate vegetable intake had 44% higher odds of being physically inactive. Regarding sedentary behaviour, our study suggested that students with inadequate fruit intake have 81% higher odds of sedentary behaviour.

We found that students who were bullied at school have higher odds for both physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour; previous research has shown that being bullied is associated with physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour (Peltzer and Pengpid 2016, (McVeigh and Meiring 2014). In a Danish study of school students aged 13–15 years old, exposure to bullying was associated with physical inactivity (Henriksen et al. 2016).

Research has also shown that family support can play an important role in the PA level of the adolescents (Tate et al. 2015, Siceloff et al. 2014, Xu et al. 2015) and, as our results show, the students with a lack of family support, parental connectivity and peer support have higher odds for being physically inactive compared to students with such supports. Previous research has shown that increased parental encouragement is positively associated with increased physical activity levels in both genders (Vander Ploeg et al. 2013). By providing facilities in terms of equipment, physically active school transportation (walking/cycling) and planning for leisure time PA, such as playing soccer or other sports with their children, parents can have an active role in increasing PA levels (Tate et al. 2015, Siceloff et al. 2014, Kuo et al. 2007). Therefore, families or guardians should be taken into consideration when planning interventions.

In one study a positive association between family and peer support at school and physical activity was found, also confirming peer and family support in terms of PA (Van Der Horst et al. 2007).

Study limitations

The present study has some limitations. First it is a cross-sectional study and does not allow establishing causality to any of the associated factors in the study. Second, the students were from an urban centre in Iran and they may not be representative of those from rural areas, and adolescents not attending school. Third, despite the anonymous nature of the study, participants may have over or under-reported when answering the questions. Fourth, the assessment in one city limits the generalizability of the findings to other cities. The desire to present a positive picture in self-reports can also affect the study results.

Conclusions

The present study showed the prevalence and correlates of physical activity/inactivity and sedentary behaviour among high-school adolescents in the city of Tabriz. The prevalence of leisure physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour in our representative sample is high. Identified risk and protective factors should be taken into consideration by public health authorities in the development and implementation of interventions aiming at promoting physical activity programmes in adolescents attending schools in the city of Tabriz.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are not available to the public because of the Internal Research Data Base Rules of the Islamic Republic of Iran. However, questionnaires will be made available to researchers upon request to the corresponding author once they have agreed to sign the non-disclosure agreements.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- NCDs:

-

non-communicable diseases

- EMRO:

-

Eastern Mediterranean Region

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- GSHS:

-

Global School-Based Students Health Survey

- CDC:

-

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- AORs:

-

Adjusted odds ratios

- UAORs:

-

Unadjusted odds ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

References

Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations — United States (2013). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6426a1.htm. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Agudo A (2004) Measuring intake of fruit and vegetables. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/f&v_intake_measurement.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Al Subhi LK, Bose S, Al Ani MF (2015) Prevalence of physically active and sedentary adolescents in 10 eastern Mediterranean countries and its relation with age, sex, and body mass index. J Phys Act Health 12:257–265. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2013-0134

Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, Musaiger AO (2011) Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits among Saudi adolescents relative to age, gender and region. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-140

American Academy of Pediatrics (2001) Children, adolescents, and television. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/107/2/423.full.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Arango CM, Parra DC, Eyler A, Sarmiento O, Mantilla SC, Gomez LF, Lobelo F (2011) Walking or bicycling to school and weight status among adolescents from Monteria, Colombia. J Phys Act Health 8(Suppl 2):S171–S177

Baharudin A et al (2014) Factors associated with physical inactivity among school-going adolescents: data from the Malaysian School-Based Nutrition Survey 2012. Asia-Pac J Public Health 26:27s–35s. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539514543682

Baygi F et al (2015) Regional disparities in sedentary behaviors and meal frequency in Iranian adolescents: the CASPIAN-III study. Iran J Pediatr 25:e182. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijp.182

Bere E, Oenema A, Prins RG, Seiler S, Brug J (2011) Longitudinal associations between cycling to school and weight status. Int J Pediatr Obes 6:182–187. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477166.2011.583656

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320:1240–1243

Collins AE, Pakiz B, Rock CL (2008) Factors associated with obesity in Indonesian adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes 3:58–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477170701520132

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:660–667

de Winter AF, Visser L, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Reijneveld SA (2016) Longitudinal patterns and predictors of multiple health risk behaviors among adolescents: the TRAILS study. Prev Med 84:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.11.028

Diet and physical activity: a public health priority (2004). https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/public-health-priority/en/#:~:text=Dietandphysicalactivity%3Aapublichealthpriority,diseases%2Ccancer%2Canddiabetes. Accessed 30 May 2019

Dumith SC, Gigante DP, Domingues MR, Kohl HW 3rd (2011) Physical activity change during adolescence: a systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol 40:685–698. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq272

Education System in Iran (n.d.). http://www.classbase.com/countries/Iran/Education-System. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Global school-based student health survey core expanded questionnaire (2009) http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/GSHS_Questionnaire_Core_Expanded_2009_English.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Global recommendations on physical activity for health (2010). http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Global school-based student health survey Item Rationale (2009) http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/GSHS_Item_Rationales_2009_English.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Global status report on non-communicable diseases (2014). http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (2004) World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Guthold R, Cowan MJ, Autenrieth CS, Kann L, Riley LM (2010) Physical activity and sedentary behavior among schoolchildren: a 34-country comparison. J Pediatr, 157:43–49.e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.019

Henriksen PW, Rayce SB, Melkevik O, Due P, Holstein BE (2016) Social background, bullying, and physical inactivity: national study of 11- to 15-year-olds. Scand J Med Sci Sports 26:1249–1255. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12574

Kelishadi R et al (2007) Association of physical activity and dietary behaviours in relation to the body mass index in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: CASPIAN study. Bull World Health Organ 85:19–26

Kuo J, Voorhees CC, Haythornthwaite JA, Young DR (2007) Associations between family support, family intimacy, and neighborhood violence and physical activity in urban adolescent girls. Am J Public Health 97:101–103. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2005.072348

Li M, Dibley MJ, Sibbritt D, Yan H (2006) Factors associated with adolescents' physical inactivity in Xi'an City, China. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38:2075–2085. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000233802.54529.87

Lord S et al (2015) Lower socioeconomic status, adiposity and negative health behaviours in youth: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open 5:e008291. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008291

Marques A, Calmeiro L, Loureiro N, Frasquilho D, de Matos MG (2015) Health complaints among adolescents: associations with more screen-based behaviours and less physical activity. J Adolesc 44:150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.07.018

McVeigh J, Meiring R (2014) Physical activity and sedentary behavior in an ethnically diverse group of south african school children. J Sports Sci Med 13:371–378

Moayeri H et al (2006) Overweight and obesity and their associated factors in adolescents in Tehran, Iran, 2004-2005. Eur J Pediatr 165:489–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0101-8

Muthuri SK, Wachira LJ, Leblanc AG, Francis CE, Sampson M, Onywera VO, Tremblay MS (2014) Temporal trends and correlates of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and physical fitness among school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:3327–3359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110303327

Pate RR, Heath GW, Dowda M, Trost SG (1996) Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents. Am J Public Health 86:1577–1581

Paudel S, Subedi N, Bhandari R, Bastola R, Niroula R, Poudyal AK (2014) Estimation of leisure time physical activity and sedentary behaviour among school adolescents in Nepal. BMC Public Health 14:637. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-637

Peltzer K, Pengpid S (2016) Leisure Time Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behaviour and Lifestyle Correlates among Students Aged 13–15 in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States, 2007–2013 Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:217 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13020217

Physical Activity Facts (2015) https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/facts.htm. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Pouliou T, Sera F, Griffiths L, Joshi H, Geraci M, Cortina-Borja M, Law C (2015) Environmental influences on children's physical activity. J Epidemiol Commun Health 69:77–85. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204287

Prentice-Dunn H, Prentice-Dunn S (2012) Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and childhood obesity: a review of cross-sectional studies. Psychol Health Med 17:255–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.608806

Siceloff ER, Wilson DK, Van Horn L (2014) A longitudinal study of the effects of instrumental and emotional social support on physical activity in underserved adolescents in the ACT trial. Ann Behav Med 48:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9571-x

State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables (2013) https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/data-statistics/2018-state-indicator-report-fruits-vegetables.html. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B (2015) Sedentary behavior and indicators of mental health in school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic review. Prev Med 76:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.026

Tassitano RM, Barros MV, Tenorio MC, Bezerra J, Florindo AA, Reis RS (2010) Enrollment in physical education is associated with health-related behavior among high school students. J School Health 80:126–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00476.x

Tate EB, Shah A, Jones M, Pentz MA, Liao Y, Dunton G (2015) Toward a better understanding of the link between parent and child physical activity levels: the moderating role of parental encouragement. J Phys Act Health 12:1238–1244. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2014-0126

Teng YK et al (2014) Influential factors of insufficient physical activity among adolescents with asthma in Taiwan. PLoS One 9:e116417. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116417

Trang NH, Hong TK, Dibley MJ, Sibbritt DW (2009) Factors associated with physical inactivity in adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41:1374–1383. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819c0dd3

Tremblay MS et al (2011) Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-98

UN Secretary-General Report (2011) Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/un_ncd_summit2011/political_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2020

Van Der Horst K, Paw MJ, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W (2007) A brief review on correlates of physical activity and sedentariness in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:1241–1250. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e318059bf35

Vander Ploeg KA, Kuhle S, Maximova K, McGavock J, Wu B, Veugelers PJ (2013) The importance of parental beliefs and support for pedometer-measured physical activity on school days and weekend days among Canadian children. BMC Public Health 13:1132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1132

Veltsista A, Kanaka C, Gika A, Lekea V, Roma E, Bakoula C (2010) Tracking of overweight and obesity in Greek youth. Obesity Facts 3:166–172. https://doi.org/10.1159/000314620

Wang X et al (2016) Correlates of insufficient physical activity among junior high school students: a cross-sectional study in Xi'an, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040397

Winkvist A, Hulten B, Kim JL, Johansson I, Toren K, Brisman J, Berteus Forslund H (2016) Dietary intake, leisure time activities and obesity among adolescents in Western Sweden: a cross-sectional study. Nutr J 15:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0160-2

Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C (2015) Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among young children: a systematic review. J Obes 2015:546925. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/546925

Ziaei R et al (2017) Suicidal ideation and its correlates among high school students in Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psych 17:147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1298-y

Ziaei R, Dastgiri S, Soares J, Baybordi E, Zeinalzadeh A, Asl Rahimi V, Mohammadi R (2014) Reliability and validity of the Persian version of Global School-based Student Health Survey. Adapt Iranian School Stud 2014(3):7. https://doi.org/10.13183/jcrg.v3i2.138

Ziaei R, Mohammadi R, Dastgiri S, Viitasara E, Rahimi VA, Jeddi A, Soares J (2016) The prevalence, attitudes, and correlates of waterpipe smoking among high school students in Iran: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9555-x

Ziaei R, Shahi H, Dastgiri S, Mohammadi R, Viitasara E (2019) Fruit and vegetable intake and its correlates among high-school adolescents in Iran: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01084-2

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants for their contribution to the study, as well as study investigators and staff. This research was possible due to collaboration between Tabriz Province Health Center, Province Ministry of Education and Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Special thanks to Mr. Abolfazl Jeddi and Mrs. Mino Mahini from the Tabriz Province Health Center, also Mr. Hamid Mehmandoost from the Province Ministry of Education.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University. This work was supported by the Research Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, under Grant number 5/4/8860. The Publication fee was funded by Mid Sweden University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RZ and SD initiated, designed and coordinated the study. EB and VR conducted data collection, HSB helped in analyzing the data, RZ wrote the manuscript, RM and EV checked the results and discussion section and critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences granted approval for the study [5/4/7180, 1391/08/10]. One week prior to the survey, consent forms were distributed to all parents of students in the participating classes through the school authorities and these were collected from students on the day of administration. In Iran, parents or legal guardians are legally responsible for their children under the age of 18; therefore, their consent was necessary. All parents or legal guardians provided consent to participate on behalf of their child. All students also were informed about the voluntary and anonymous nature of the study and were told that they could terminate their participation at any time during the survey.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflict of interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziaei, R., Mohammadi, R., Dastgiri, S. et al. The prevalence and correlates of physical activity/inactivity and sedentary behaviour among high-school adolescents in Iran: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 1121–1131 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01392-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01392-y