Summary

Importance

Fundoplication (FP) is a well-established surgical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refractory to medical therapy in children and young adults. During FP, previous abdominal surgery (PAS) can impair the patient’s outcome by causing technical difficulties and increasing intra- and postoperative complication rates.

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of PAS on the short- and long-term outcome following FP for refractory GERD in a cohort of patients aged < 23 years.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 182 patients undergoing a total of 201 FP procedures performed at our university center for pediatric surgery from February 1999 to October 2019. Pre-, intra-, and postoperative variables were recorded and their impact on the rate of intraoperative complications and revision FP (reFP) was analyzed.

Results

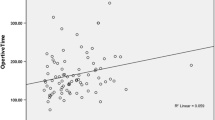

A total of 201 FP procedures were performed on 182 patients: 119 (59.2%) as Thal-FP (180° anterior wrap) and 82 (40.8%) as Nissen-FP (360°circular wrap; 67.2% laparoscopic, 32.8% open, 8.9% conversion). The presence of PAS (95 cases, 47.3%) was associated with significantly longer operative times for FP (153.4 ± 53.7 vs.126.1 ± 56.4 min, p = 0.001) and significantly longer hospital stays (10.0 ± 7.0 vs. 7.0 ± 4.0 days, p < 0.001), while the rates of intraoperative surgical complications (1.1% vs. 1.9%, p = 1.000) and the rate re-FP in the long term (8.4% vs. 15.1%, p = 0.19) during a follow-up period of 53.4 ± 44.5 months were comparable to the group without PAS.

Conclusion

In cases of PAS in children and young adults, FP for refractory GERD might necessitate longer operative times and longer hospital stays but can be performed with surgery-related short- and long-term complication rates comparable to cases without PAS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

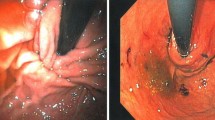

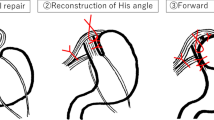

Fundoplication (FP) is the antireflux surgery treatment of choice for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refractory to medical therapy in children and young adults (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). It leads to effective symptom control, reduction of GERD medication, and improved postoperative quality of life for patients [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Previous abdominal surgery (PAS) can make FP technically more challenging for the surgeon, mostly due to intrabdominal adhesions that lead to suboptimal intraoperative line of sight [8,9,10]. The impact of PAS on these patients is debated. It was previously reported that PAS can be associated with prolonged operative times, increased conversion and complications rates [11, 12], and poorer postoperative outcome [11,12,13,14]. However, others report comparable morbidity and functional results with and without PAS [8, 15,16,17]. The aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of PAS on FP-related short- and long-term outcome in a cohort of patients < 23 years of age following FP for medically refractory GERD.

Material and methods

Study population and data acquisition

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (S-272-2019 and S-638/2011). We retrospectively analyzed patients (age < 23 years) following FP for medically refractory GERD at our university center for pediatric surgery from February 1999 to October 2019. Study inclusion criteria were follow-up longer than 6 months after FP and the availability of complete study data. Study exclusion criteria were patients with previous solid-organ transplantations.

Study data were retrieved from the electronic patients’ charts and included demographic data (gender, age at surgery, weight at surgery, height at surgery), preoperative data (diagnosis, comorbidities, previous abdominal operation), perioperative data (operative time, type of operation [laparoscopic vs. open operation], need for conversion to open surgery, type of FP [Nissen or Thal], occurrence and grade of postoperative surgical complications according to the ‘Clavien–Dindo’ classification [18]) and outcome data (length of hospital stay, length of follow-up, symptoms, need for redo FP). Short-term outcome was defined as the rate of surgical complications within the first 30 postoperative days and the long-term outcome was defined as the rate of Re-FP up to the latest available postoperative data.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistic Version 25 (IBM Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages and were compared using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were compared by a two-tailed paired t test. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to determine the impact on patient outcome for each recorded variable. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Overall group

A total of 302 children and young adults underwent FP during the study period. Of these, 128 (38.9%) cases were excluded due to the following criteria: lost to follow-up (n = 64, 19.5%), available data of follow-up less than 6 months (n = 55, 16.7%), incomplete data sets (n = 5, 1.5%), and previous organ transplantation (n = 4, 1.2%). The study group included 182 patients who underwent a total of 201 FP procedures.

Intraoperative complications included bleeding from a stomach vessel (n = 3), which could not be resolved laparoscopically and required a conversion to an open suture in two cases. Postoperative surgical complications leading to a reintervention within the first 30 postoperative days following FP included a laparoscopic release of a tight hiatoplasty suture as a cause of early and persistent postoperative dysphagia (n = 1), relaparotomy for secondary gastric perforation (n = 3) and leakage of a gastrostomy (n = 1), relaparotomy for dislocation of a gastrostomy tube with peritonitis (n = 1), and drainage of an abdominal abscess (n = 1).

In 24 cases (11.9%) a re-FP was necessary for recurrent and medically refractory GERD within the follow-up period of 53.4 ± 44.5 months. During this follow-up period, there was no operation-related mortality, although four neurologically impaired children (2.0%) died due to cardiorespiratory failure unrelated to surgery.

Effect of a previous abdominal surgery

Overall, 95 (47.3%) of the FP procedures were performed after a PAS. The previous operations are described in Table 1. The subgroup analysis results between patients with and without PAS at the time of FP are presented in Table 2.

A PAS at the time of FP was associated with an odds ratio of 1.808 (95% CI 0.161–20.260, p = 0.631) for intraoperative complications and an odds ratio of 1.933 (95% CI 0.787–4.748; p = 0.150) for a redo FP.

Gastrostomy was performed in one third of cases before FP (67/201 = 33.3%). These patients showed comparable surgery times at FP (148.4 ± 47.5 min. vs. 134.3 ± 60.4 min; p = 0.069) and intraoperative complication rates (1/67 = 1.5% vs. 2/134 = 1.5%; p = 1.000). The length of hospital stay was also significantly longer for patients with gastrostomy (10.9 ± 7.7 days vs. 7.2 ± 3.9 days; p < 0.001) than for patients without previous gastrostomy. The need for redo FP was comparable between both groups (6/67 = 9.0% with gastrostomy vs. 18/34 = 53.0% without gastrostomy, p = 0.490) and a gastrostomy at the time of FP was associated with an odds ratio of 0.634 (95% CI 0.239–1.680, p = 0.359) for the need of a redo FP.

Patients with FP as a PAS showed comparable operation times (156.6 ± 54.6 min. vs. 136.2 ± 56.7 min.; p = 0.088) and intraoperative complication rates (1/27 = 3.7% vs. 2/174 = 12%, p = 0.523). The length of hospital stay was significantly longer (6.9 ± 3.0 days vs. 8.6 ± 6.0 days; p = 0.154) compared to patients without previous FP.

Fundoplication as PAS at the time of FP was associated with an odds ratio of 3.308 (95% CI 0.290–37.784, p = 0.336) for intraoperative complications and an odds ratio of 0.553 (95% CI 0.122–2.497; p = 0.553) for the need for redo FP.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of PAS on the FP-related outcome in a cohort of children and young adults undergoing FP for medically refractory GERD. We showed that PAS was associated with a significantly longer operation time and hospital stay, and, as the rate of intraoperative complications and the rate of redo FP were not significantly different, the presence of PAS did not have a significant influence on the overall outcome of the patients.

This is accordance with the literature regarding the safety of performing FP in children with PAS, such as gastrostomy or ventriculo-peritoneal shunts [15, 36], previous FP [10, 33], or other laparotomies [8, 29].

The clearly extended time of operation is most likely due to adhesions caused by the PAS, which may lead to suboptimal intraoperative line of sight and a technically more demanding operation [11, 12]. According to the literature, in our study PAS was associated with a higher conversion rate during FP (0–11%; [6, 8, 11, 12, 19,20,21,22,23]). Although the operation time was longer and the conversion rate was higher in children with PAS compared to children without PAS, both groups showed comparable intraoperative complication rates. These results are almost identical to results in the current literature since the overall intraoperative complication rates are reported as 0.8–14% [11, 12, 19,20,21, 24, 25] and as 0–17% in children with PAS [10, 14,15,16,17, 22, 26].

The laparoscopic approach for FP is associated with a shorter hospital stay [11, 27, 28]. This possibly explains the longer hospital stay in children with PAS in the present study, as in these patients the open FP rate was significantly higher than for children without PAS. Moreover, the longer hospital stay in children with PAS could also be partly due to the higher rate of neurologically impaired patients in this group, since according to the literature a significant comorbidity might prolong the hospital stay [11].

In present study, the redo FP rate for patients and young adults with PAS was comparable to the rate reported in the literature (0–18%; [8, 10, 29,30,31]). Although the regression analysis showed a tendency for a higher rate of redo FP in children with PAS, this was not statistically significant.

In some studies, the presence of a gastrostomy is mentioned as a major factor for the occurrence of postoperative complications following a pediatric FP [21, 25]. In our analysis, the postoperative complication rate was not influenced by the presence of PAS; however, the length of hospitalization was significantly longer in children with PAS and gastrostomy. In patients with a neurological impairment, gastrostomy was found significantly more frequently in our study, and therefore the presence of such a comorbidity could be a contributory cause to the prolonged hospital stay [11].

The presence of a previous FP as PAS did not impact the complications rate, the operation time, or the need for redo FP in the present study, while the rates of these parameters were comparable to published data [9, 10, 30, 32,33,34,35].

This study is limited by the single-center analysis, which limits the size of the study population and the retrospective nature of the study, leading to potential bias. A considerably higher number of cases for accurate evaluation might be accomplished through the widespread use of a centralized register. Moreover, a prospective, blind, randomized, two-arm study could avoid this bias and determine the procedure-related impact with more accuracy. However, such a study is probably unfeasible for ethical reasons; therefore, retrospective studies like ours currently represent one possible source of data on which to base recommendations in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

In children and young patients with a previous abdominal surgery, fundoplication can be performed safely for medically refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. A previous abdominal surgery does not represent a contraindication or a limitation to performing fundoplication on these patients.

References

Sherman P, Hassall E, Ulysses F, Gold B, Kato S, Koletzko S, et al. A Global, Evidence-Based Consensus on the Definition of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in the Pediatric Population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 May 1;104:1278–95; quiz 1296. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2009.129.

Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, Di Lorenzo C, Gottrand F, et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr [Internet]. 2018 Mar [cited 2020 Mar 22];66(3):516–54. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5958910/.

Frongia G, Ahrens P, Capobianco I, Kössler-Ebs J, Stroh T, Fritsche R, et al. Long-term effects of fundoplication in children with chronic airway diseases. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(1):206–10. Jan.

Frongia G, Weitz D, Bauer J, Probst P, Steffens F, Pfisterer D, et al. Quality of Life Improves Following Laparoscopic Hemifundoplication in Neurologically Non-Impaired Children with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Investig Surg Off J Acad Surg Res. 2020 Nov 29;1–6.

Loots C, van Herwaarden MY, Benninga MA, VanderZee DC, van Wijk MP, Omari TI. Gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal function, gastric emptying, and the relationship to dysphagia before and after antireflux surgery in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(3):566–573.e2.

Mauritz FA, van Herwaarden-Lindeboom MYA, Stomp W, Zwaveling S, Fischer K, Houwen RHJ, et al. The effects and efficacy of antireflux surgery in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2011 Oct;15(10):1872–8.

Soyer T, Karnak I, Tanyel FC, Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, Büyükpamukçu N. The use of pH monitoring and esophageal manometry in the evaluation of results of surgical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Pediatr Surg Off J Austrian Assoc Pediatr Surg Al Z Kinderchir. 2007 Jun;17(3):158–62.

Barsness KA, St Peter SD, Holcomb GW, Ostlie DJ, Kane TD. Laparoscopic fundoplication after previous open abdominal operations in infants and children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009 Apr;19 Suppl 1:S47–49.

Miyano G, Yamoto M, Miyake H, Morita K, Kaneshiro M, Nouso H, et al. A Comparison of Laparoscopic Redo Fundoplications for Failed Toupet and Nissen Fundoplications in Children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Apr 10];24(2):100–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6417062/.

Rothenberg SS. Laparoscopic redo Nissen fundoplication in infants and children. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(10):1518–20. Oct.

Kubiak R, Böhm-Sturm E, Svoboda D, Wessel LM. Comparison of long-term outcomes between open and laparoscopic Thal fundoplication in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(7):1069–74. Jul.

Mathei J, Coosemans W, Nafteux P, Decker G, De Leyn P, Van Raemdonck D, et al. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in infants and children: analysis of 106 consecutive patients with special emphasis in neurologically impaired vs. neurologically normal patients. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(4):1054–9. Apr.

Kubiak R, Skerritt C, Grant HW. Laparoscopic fundoplication in children with ventriculo-peritoneal shunts. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22(8):840–3. Oct.

Walker DH, Langer JC. Laparoscopic surgery in children with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(7):1104–5. Jul.

Liu DC, Flattmann GJ, Karam MT, Siegrist BI, Loe WA, Hill CB. Laparoscopic fundoplication in children with previous abdominal surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(2):334–7. Feb.

Kimura T, Nakajima K, Wasa M, Yagi M, Kawahara H, Soh H, et al. Successful laparoscopic fundoplication in children with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(1):215. Jan.

van der Zee DC, Bax NM, Ure BM. Laparoscopic secondary antireflux procedure after PEG placement in children. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(12):1105–6. Dec.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13. Aug.

Capito C, Leclair MD, Piloquet H, Plattner V, Heloury Y, Podevin G. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication for neurologically impaired and normal children. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2008 Apr 1 [cited 2020 Oct 9];22(4):875–80. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00464-007-9603-3.

Esposito C, Montupet Ph, van Der Zee D, Settimi A, Paye-Jaouen A, Centonze A, et al. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen, Toupet, and Thal antireflux procedures for neurologically normal children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc Interv Tech [Internet]. 2006 Jun 1 [cited 2020 Apr 6];20(6):855–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-005-0501-2.

Kubiak R, Andrews J, Grant HW. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus Thal fundoplication in children: comparison of short-term outcomes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20(7):665–9. Sep.

Lintula H, Antila P, Kokki H. Laparoscopic fundoplication in children with a preexisting gastrostomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13(6):381–5. Dec.

Booth MI, Jones L, Stratford J, Dehn TCB. Results of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication at 2–8 years after surgery. Br J Surg. 2002;89(4):476–81. Apr.

Esposito C, Montupet P, Amici G, Desruelle P. Complications of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in childhood. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(7):622–4. Jul.

Esposito C, Van Der Zee DC, Settimi A, Doldo P, Staiano A, Bax NMA. Risks and benefits of surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux in neurologically impaired children. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(5):708–10. May.

Smith CD, McClusky DA, Rajad MA, Lederman AB, Hunter JG. When Fundoplication Fails. Ann Surg [Internet]. 2005 Jun [cited 2020 Apr 10];241(6):861–71. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1357166/.

Barnhart DC. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Semin Pediatr Surg [Internet]. 2016 Aug 1 [cited 2020 Mar 25];25(4):212–8. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1055858616300257.

Fox D, Morrato E, Campagna EJ, Rees DI, Dickinson LM, Partrick DA, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic versus open fundoplication in children’s hospitals: 2005–2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):872–80. May.

Barsness KA, Feliz A, Potoka DA, Gaines BA, Upperman JS, Kane TD. Laparoscopic versus open Nissen fundoplication in infants after neonatal laparotomy. JSLS. 2007;11(4):461–5. Dec.

Desai AA, Alemayehu H, Dalton BG, Gonzalez KW, Biggerstaff B, Holcomb GW, et al. Review of the Experience with Re-Operation After Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016;26(2):140–3. Feb.

Verbelen T, Lerut T, Coosemans W, De Leyn P, Nafteux P, Van Raemdonck D, et al. Antireflux surgery after congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: a plea for a tailored approach. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2013 Aug;44(2):263–7; discussion 268.

Celik A, Loux TJ, Harmon CM, Saito JM, Georgeson KE, Barnhart DC. Revision Nissen fundoplication can be completed laparoscopically with a low rate of complications: a single-institution experience with 72 children. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(12):2081–5. Dec.

Esposito C, Becmeur F, Centonze A, S’ettimi A, Amici G, Montupet P. Laparoscopic Reoperation Following Childhood Unsuccessful Antireflux Surgery in Childhood. Semin Laparosc Surg [Internet]. 2002 Sep 1 [cited 2020 Oct 8];9(3):177–9. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/155335060200900310.

Floch NR, Hinder RA, Klingler PJ, Branton SA, Seelig MH, Bammer T, et al. Is laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux surgery feasible? Arch Surg Chic Ill. 1960;1999(Jul;134(7):733–7.

Baerg J, Thorpe D, Bultron G, Vannix R, Knott EM, Gasior AC, et al. A multicenter study of the incidence and factors associated with redo Nissen fundoplication in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1306–11. Jun.

Cheng AW, Shaul DB, Lau ST, Sydorak RM. Laparoscopic redo nissen fundoplication after previous open antireflux surgery in infants and children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24(5):359–61. May.

Funding

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F.C. Steffens, M. Dahlheim, P. Günther, A. Mehrabi, R. N. Vuille-Dit-Bille, U. K. Fetzner, B. Gerdes, and G. Frongia declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The conduct of the present study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty Heidelberg (S-272-2019 and S-638/2011).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steffens, F.C., Dahlheim, M., Günther, P. et al. Impact of previous abdominal surgery on the outcome of fundoplication for medically refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease in children and young adults. Eur Surg 55, 20–25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00775-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00775-7