Abstract

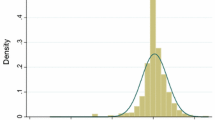

Theoretically, reallocating an input from a firm where the input has low marginal product to a firm where the input has high marginal product would increase aggregate productivity without any underlying change in technology. This paper argues that measuring these reallocation effects requires accounting for detailed input types because, for example, differences in wages across producers often reflect the skill mix of workers, not allocative inefficiency. The paper develops an approach to measuring reallocation that accounts for worker skill and the composition of capital assets, thus focuses on the set of countries for which this information is available. The results show once input heterogeneity is accounted for, the effects of reallocation on aggregate productivity were small on average, but sizable in a subset of countries. Panel regressions indicate that reallocation effects are related to population distribution and government effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An underlying assumption in this paper, as in Basu and Fernald (2002) and Hsieh and Klenow (2009) is that the inputs and output data are measured without error. There are no adjustments for worker effort, for example, or capital utilization. While taking these into account would likely smooth both aggregate TFP and aggregate technology, these effects likely cancel out over the business cycle.

This approach was recently updated by Jorgenson et al. (2007).

Note that they do mention this as a possible extension to their analysis.

Jorgenson et al. (2005) estimates that between 1977 and 2000 substitution towards capital types with higher marginal products (capital quality) accounted for about 25% of GDP growth in the U.S., while shifts towards workers with higher marginal products accounted for about 7% of aggregate growth. Put another way, aggregate TFP growth would be mismeasured by about a factor of two if one ignored these composition effects.

All weights used below are averages of period t and t − 1 weights, indicated by a bar over the weight variable.

Additional conditions are required for measured v T,j to correspond to technological change including marginal product pricing, frictionless adjustment, and perfect competition, which are assumed to hold in the analysis below.

It could be the case that the output of industry j is also used as an input into the production of industry j, in which case this is treated as both an output and an input. For purposes of calculating value added, this is subtracted from the value of output just as any other intermediate input.

Measures of real value added, industry technology, and aggregate TFP also require intermediate purchases adjusted for heterogeneity, but the underlying assumption in the construction of the data is that each industry pays the same price for the detailed input, so there is no reallocation effect from intermediate prices by assumption.

Note that factor market frictions do not necessarily rule out marginal product pricing of inputs.

Note that this formulation abstracts from the role of taxation, which is potentially important due to depreciation deductions, and investment tax credits, for example. See Jorgenson and Yun (2002) for more discussion of the role of taxes in the cost of capital.

For example, an investor in expectation earns rate of return i j,t as an alternative investment.

There are probably some unmeasured benefits and costs in labor compensation measures, such as direct health care services that used to be provided by companies, but are now subsidized (appearing in labor compensation) and outsourced.

The labor data is classified as low, medium, and high skill based on the level of educational attainment. Generally, high skill is a college degree and above. Medium is high school or technical school, and low is all other workers. There are some differences that make comparisons of levels across countries difficult, but the analysis below pertains to within country growth over time.

The aggregate value added price is distinct from the aggregate GDP price. Both measure output prices consistent with the production of new goods and services, but the GDP price is constructed as an index over expenditure side data, while the value added price is constructed as an index over industry value added. Both price measures are included in the national accounts of the U.S.

Basu and Fernald (2002) discusses the use of industry-level data instead of firm-level data.

See http://www.euklems.net for a detailed description of the underlying data.

The industry level of detail in the original data is slightly different than the figures presented here. The figures below are based on a common classification and the reallocation effects for this common classification are the sum of the industry effects calculated at the original level of detail.

Note that the economy-wide rates of return are the implicitly the weighted average rates of return with income shares as weights.

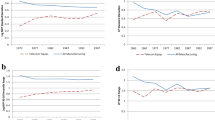

For 10 out of 13 in particular. Note that labor the labor reallocation in Sweden is not available due to limited data. Table A2 of supplementary material presents these variances, and the correlations of the capital and reallocation effects across industries by country.

See Gibbons and Katz (1992) for an empirical assessment of inter-industry wage differentials.

To reconcile the potentially counter-intuitive findings that the capital and labor effects are positively correlated across industries with the finding that labor reallocations dampened TFP while capital reallocation contributed positively consider this example: in Austria, capital and labor reallocations were positively correlated. The coefficient was 0.77. For the country as a whole the capital reallocation contributed 0.18 pp to aggregate productivity growth, while labor reallocation contributed -0.06. These two results can be reconciled by noticing that in the Real Estate and business activities industry, the capital reallocation effect is significantly larger than the labor reallocation effect, but both contributed positively to aggregate TFP growth. The relatively smaller contribution from labor reallocation in this industry was not enough to offset the negative contributions from other industries, so the aggregate contribution of the labor reallocation effect was negative, while the aggregate capital effect was positive.

Table A3 of supplementary material includes regressions of the reallocation effects on a dummy variable for the service industries. Service industries are defined as Construction, Wholesale And Retail Trade, Hotels And Restaurants, Transport And Storage, Post And Telecommunications, Financial Intermediation, Real Estate, Renting And Business Activities, Community Social And Personal Services, Education, Health And Social Work. The result is robust to dropping the Real estate, renting and business activities sector and the Construction sector.

It is also worth noting again that variables are assumed to be measured without error. There is a large literature on the difficulties in measurement of the service sectors. Most of this literature focused on the output of the service sector. The reallocation estimates rely on estimates of wages and rental rates by industry, which are not fraught with the same difficulty as the output of the service sectors. Nevertheless, measurement issues cannot be completely ruled out as an important factor in these results. An important deficiency is that the capital accounts in EUKLEMS exclude land.

Results in Lee and Wolpin (2006) indicate substantial mobility costs to moving labor in the U.S., suggesting that the reallocation effects would have been larger without these costs.

Productivity is measured as GDP per employee. Following Gruber and Kamin (2007), productivity, the interest rate, and the age dependency ratios were entered as differences from the GDP weighted mean.

Defined as GDP growth less average GDP growth over the period for each country, in absolute value.

The governance variable used here is a simple average of the six indicators in the World Wide Governance Indicators. Higher values indicate higher effectiveness.

Robust standard errors are reported; bootstrapped robust standard errors yield similar results.

References

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2005). Growth theory through the lens of development economics. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 473–552.

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 407–443.

Bartelsman, E., Haltiwanger, J., & Scarpetta, S. (2013). Cross-country differences in productivity: The role of allocation and selection. The American Economic Review, 103, 305–334.

Basu, S., & Fernald, J. G. (2002). Aggregate productivity and aggregate technology. European Economic Review, 46, 963–991.

Christensen, L. R., Jorgenson, D. W., & Lau, L. J. (1973). Transcendental logarithmic production frontiers. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 55(1), 28–45.

Denison, E. F., et al. (1967). Why Growth Rates Differ. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Syverson, C. (2008). Reallocation, firm turnover, and efficiency: Selection on productivity or profitability? American Economic Review, 98, 394–425.

Gibbons, R., & Katz, L. (1992). Does unmeasured ability explain inter-industry wage differentials? The Review of Economic Studies, 59, 515–535.

Gruber, J. W., & Kamin, S. B. (2007). Explaining the global pattern of current account imbalances. Journal of International Money and Finance, 26, 500–522.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. J. (2009). Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1403–1448.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. J. (2010). Development accounting. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2, 207–223.

Jorgenson, D., Gollop, F., & Fraumeni, B. (1987). Productivity and U.S. Economic Growth, North-Holland.

Jorgenson, D., & Griliches, Z. (1967). The explanation of productivity change. The Review of Economic Studies, 34, 249–283.

Jorgenson, D. W., Ho, M. S., & Samuels, J. D. (2014). What will revive US economic growth? Lessons from a prototype industry-level production account for the United States. Journal of Policy Modelling, 4, 674–691.

Jorgenson, D. W., Ho, M. S., Samuels, J. D., & Stiroh, K. J. (2007). Industry origins of the American productivity resurgence. Economic Systems Research, 19, 229–252.

Jorgenson, D., Ho, M., & Stiroh, K. (2005). Information technology and the American growth resurgence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jorgenson, D. W., & Yun, K.-Y. (2002). Investment, volume 3: Lifting the burden: Tax reform, the cost of capital, and US economic growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Books.

Lee, D., & Wolpin, K. I. (2006). Intersectoral labor mobility and the growth of the service sector. Econometrica, 74, 1–46.

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 407–437.

Michaels, G., Natraj, A., & Van Reenen, J. (2014). Has ICT polarized skill demand? Evidence from eleven countries over twenty-five years. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96, 60–77.

Timmer, M. P., Los, B., Stehrer, R., & De Vries, G. J. (2013). Fragmentation, incomes and jobs: An analysis of European competitiveness. Economic Policy, 28, 613–661.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mun Ho, Dale Jorgenson, Rachel Soloveichik, and seminar participants at the North American Productivty Workship and Society of Economic Measurment for useful discussions. The anonymous referee provided very helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Samuels, J.D. Assessing aggregate reallocation effects with heterogeneous inputs, and evidence across countries. Rev World Econ 153, 385–410 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0273-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0273-x