Abstract

In many fiber-reinforced tissues, collagen fibers are embedded within a glycosaminoglycan-rich extrafibrillar matrix. Knowledge of the structure–function relationship between the sub-tissue properties and bulk tissue mechanics is important for understanding tissue failure mechanics and developing biological repair strategies. Difficulties in directly measuring sub-tissue properties led to a growing interest in employing finite element modeling approaches. However, most models are homogeneous and are therefore not sufficient for investigating multiscale tissue mechanics, such as stress distributions between sub-tissue structures. To address this limitation, we developed a structure-based model informed by the native annulus fibrosus structure, where fibers and the matrix were described as distinct materials occupying separate volumes. A multiscale framework was applied such that the model was calibrated at the sub-tissue scale using single-lamellar uniaxial mechanical test data, while validated at the bulk scale by predicting tissue multiaxial mechanics for uniaxial tension, biaxial tension, and simple shear (13 cases). Structure-based model validation results were compared to experimental observations and homogeneous models. While homogeneous models only accurately predicted bulk tissue mechanics for one case, structure-based models accurately predicted bulk tissue mechanics for 12 of 13 cases, demonstrating accuracy and robustness. Additionally, six of eight structure-based model parameters were directly linked to tissue physical properties, further broadening its future applicability. In conclusion, the structure-based model provides a powerful multiscale modeling approach for simultaneously investigating the structure–function relationship at the sub-tissue and bulk tissue scale, which is important for studying multiscale tissue mechanics with degeneration, disease, or injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Many soft tissues in the body include highly aligned collagen fibers embedded in a glycosaminoglycan-rich extrafibrillar matrix. The matrix allows for water and nutrient absorption, which is important for maintaining tissue homeostasis (Yang and O’Connell 2019), while fibers create anisotropic mechanical properties that allow the tissue to withstand large tensile loads. For example, tendons and ligaments have a single family of fibers, providing the tissue with greater stiffness along the primary in situ loading direction (Benjamin and Ralphs 1997). Meanwhile, tissues that undergo multiaxial loadings have more complex fiber networks, from two fiber populations, such as arterial walls and the annulus fibrosus (AF) of the intervertebral disk (Holzapfel et al. 2000; Adams and Roughley 2006), to randomly distributed fibers, such as skin (Cotta-Pereira et al. 1976).

Structural and mechanical behaviors of fibers and the matrix have been shown to change with degeneration, disease, and injury. For example, the AF has a cross-ply fiber structure (Cassidy et al. 1989; Marchand and Ahmed 1990), where collagen fibers can reorient under tensile loading. The amount of fiber reorientation has been shown to decrease with degeneration (Guerin and Elliott 2006), partly due to matrix stiffening and increased collagen cross-linking (Fujita et al. 1997; Wagner et al. 2006; O’Connell et al. 2011), which can lead to increased stress concentrations within the disk, triggering catabolic remodeling that can cause tissue failures (Antoniou et al. 1996; Adams and Roughley 2006). Failure of these fiber-reinforced tissues can cause a wide range of clinical issues, from mechanical dysfunctions of the disk to death (e.g., a ruptured aneurysm) (Juvela et al. 2000; Rubin 2007; Erwin and Hood 2014; O’Connell et al. 2015). Therefore, it is important to understand the role sub-tissue properties (e.g., fiber networks, matrix biochemical compositions, etc.) play on bulk tissue mechanics.

Although experimental studies have provided important information regarding bulk tissue mechanics, there are few studies that have directly measured sub-tissue properties due to challenges in conducting tests on individual tissue subcomponents. Thus, many researchers have complemented experimental data with structure-based constitutive modeling (Spencer 1984) to investigate tissue structure–function relationships. Commonly, in these studies, phenomenological strain energy density functions developed based on the model are curve fit to experimental data of bulk tissue mechanics to calibrate for model parameters that describe the structural contributions of tissue subcomponents and their interactions. The structure-based constitutive models have been valuable for highlighting the importance of fiber–matrix interactions with respect to degeneration and different loading conditions (Wu and Yao 1976; Klisch and Lotz 1999; Elliott and Setton 2001; Bass et al. 2004; Wagner and Lotz 2004; Yin and Elliott 2005; Peng et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2006; Guerin and Elliott 2007; Nerurkar et al. 2008, 2011; O’Connell et al. 2009, 2012). However, these models often include a large number of hypothesized invariant terms, generating nonunique model parameters that cannot be easily compared or applied across studies (Yin and Elliott 2005; Guo et al. 2012). Directly linking model parameters to tissue physical properties and measurable tissue compositional changes has also been difficult as most parameters are not physically interpretable (Yin and Elliott 2005; Eskandari et al. 2019).

Additionally, the constitutive models normally performed poorly in simultaneously predicting tissue mechanics under multiple test configurations, due to the commonly applied model parameter calibration approach. Typically, the models are calibrated by curve fitting to study-specific stress–strain curves, often from a single test configuration (Sun et al. 2005; Schmidt et al. 2006, 2007), resulting in a limited model accuracy and robustness under other loading modalities. For example, previous work showed that constitutive models calibrated to uniaxial tension data were not able to accurately predict mechanical behaviors under biaxial tension or simple shear (Bass et al. 2004; O’Connell et al. 2012). Simultaneous curve fitting to multiple loading modalities has also proved challenging, often resulting in relatively poor model fits (Klisch and Lotz 1999; Wagner et al. 2006).

To address some of these issues, there has been a growing interest in using finite element models (FEM) to study three-dimensional tissue deformations. So far, most bulk tissue-scale FEMs employ homogenization theory, where every model element includes a combined and homogenized description of tissue subcomponents (e.g., fibers and the matrix) (Bensoussan et al. 1978; Sanchez-Palencia and Zaoui 1987; Jones 1999; Yin and Elliott 2005). This approach has allowed researchers to study three-dimensional stress and strain distributions, which has been valuable for predicting peak strains at failure (Eberlein et al. 2001) and for directing experimental protocol designs (Jacobs et al. 2013; Werbner et al. 2017). Unfortunately, homogenization of tissue subcomponents does not accurately represent the heterogeneous architecture of native tissues, where fibers and the extrafibrillar matrix are distinct materials that occupy separate volumes. Therefore, these models are not capable of describing and explaining some recent experimental observations, including variations in collagen fibril diameter with osmotic loading and changes in interfibrillar strain field with mechanical loading (Han et al. 2012; Vergari et al. 2016).

To address the limitations of the discussed modeling approaches, the objective of this study was to develop and validate a structure-based FEM that can be used to investigate multiscale structure–function relationships of fiber-reinforced tissues. To do so, we developed a model based on the native heterogeneous structure of the human AF, where fibers and the extrafibrillar matrix were described as two distinct materials occupying separate volumes (SEP model). The model was calibrated and validated using a multiscale framework. Model parameters were calibrated to sub-tissue-scale mechanical test data (Holzapfel et al. 2005), while model was validated at the bulk scale by comparing model-predicted multiaxial mechanics of multi-lamellar structures with multi-lamellar experimental test data. Multi-lamellar models developed using homogenization theory (HOM models) were also created, and their validation results were compared to results from the multiscale structure-based models. The second objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between specimen geometry and bulk tissue mechanics using the validated multiscale structure-based model. Although this study was conducted using AF morphology, the approaches and techniques employed here are applicable to other fiber-reinforced biological tissues and composites.

2 Methods

2.1 Model development

Finite element models were developed with geometry and dimensions representative of specimens used in uniaxial tensile testing of the AF (SolidWorks 2017; Abaqus 6.14; ANSA 15.2.0; PreView 1.19.0; and FEBio 2.5.2, ~ 0.5–1 million tetrahedral elements, depending on specimen geometry). Each lamella had a thickness of 0.2 mm, based on native tissue properties (Marchand and Ahmed 1990). Previous experimental data suggested that AF modulus can change with specimen thickness (Żak and Pezowicz 2013, 2016). Thus, preliminary work was performed to determine whether specimen thickness, determined by the number of lamellae included in the model, affected bulk tissue modulus. To do this, a series of FEMs with identical specimen length and width but different thicknesses (i.e., number of lamellae) were developed to represent uniaxial tensile testing specimens along the axial direction (Fig. 1a).

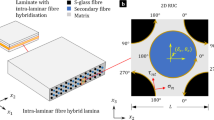

a Schematic of model orientation (circumferential: circ.; axial: ax.). b Separate model (SEP) described the extrafibrillar matrix and fiber bundles as two distinct materials that occupied separate volumes. c Single-lamellar models were used for model parameter calibration to experimental data (EXP) in the low-, medium-, and high-stress regions of the stress–strain curve (Elow, Emed, and Ehigh, respectively) (Holzapfel et al. 2005). d After model calibration, multi-lamellar models were developed for validation. Bulk tissue mechanical properties were predicted and compared to data in the literature

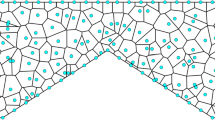

A structure-based approach was employed during SEP model development to describe the AF as a fiber-reinforced composite containing distinct materials for the extrafibrillar matrix (matrix) and fiber bundles (SEP for “separate model”; Fig. 1b). Fiber bundles (fibers) were described as being uniformly distributed, full-length cylinders welded to the surrounding matrix (Shirazi-Adl et al. 1984; Goel et al. 1995; Michalek et al. 2009; Schollum et al. 2010). The radius of each fiber bundle was 0.06 mm, and interfibrillar spacing within each lamella was 0.22 mm (Marchand and Ahmed 1990). Fiber bundles were oriented at ± 30° (Fig. 1b—\(\theta = 30^\circ\)) to the transverse plane to represent specimens prepared from the middle-outer AF (Cassidy et al. 1989).

Triphasic mixture theory was employed to describe swelling in both SEP and HOM models to account for tissue hydration (Lai et al. 1991; Ateshian et al. 2004). Tissue permeability (k) was described as being strain-dependent (Holmes–Mow description; Eq. 1):

In Eq. 1, \(J\) is the determinant of the deformation gradient tensor (F), \(k_{0}\) is represented hydraulic permeability in the reference state (\(k_{0} = 0.0064\) mm4/N s), \(\varphi_{0}\) represents the solid volume fraction (\(\varphi_{0} = 0.3\)), \(\alpha\) represents the power-law exponent (\(\alpha = 2\)), and \(M\) represents exponential strain-dependence coefficient (\(M = 4.8\)) (Mow et al. 1984; Antoniou et al. 1996; Iatridis et al. 1998; Gu et al. 1999; Beckstein et al. 2008; Cortes et al. 2014; O’Connell et al. 2015). Fixed charge density, which represents the tissue proteoglycan content and drives tissue swelling, was set to -100 mmol/L for the matrix (middle-outer AF) and 0 mmol/L for fibers (i.e., no active swelling in the fibers) (Urban and Maroudas 1979; Huyghe et al. 2003). The osmotic coefficient (0.927) was determined using a linear interpolation of the data reported in Robinson and Stokes (1949) and Partanen et al. (2017). Free diffusivity (\(D_{0} )\) and AF tissue diffusivity (DAF) of Na+ and Cl− were set based on data in Gu et al. (2004), and 100% ion solubility was assumed (\(D_{{0,{\text{Na}}^{ + } }} = 0.00116\) mm2/s; \(D_{{0,{\text{Cl}}^{ - } }} = 0.00161\) mm2/s; \(D_{{{\text{AF}},{\text{Na}}^{ + } }} = 0.00044\) mm2/s; \(D_{{{\text{AF}},{\text{Cl}}^{ - } }} = 0.00069\) mm2/s).

For SEP models, the matrix was modeled as a compressible hyperelastic material using the neo-Hookean description (Bonet and Wood 1997) (Eq. 2), where \(I_{1}\) and \(I_{2}\) are the first and second invariants of the right Cauchy–Green deformation tensor, \(\varvec{C }\left( {\varvec{C} = \varvec{F}^{\text{T}} \varvec{F}} \right)\) (Maas et al. 2012). \(E_{\text{matrix}}\) and \(\nu_{\text{matrix}}\) represent the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the matrix. Fiber bundles in SEP models were described as a compressible hyperelastic ground matrix substance reinforced by power-linear fibers. The ground matrix substance was described using the Holmes–Mow material description, where \(I_{1}\), \(I_{2}\), \(J\), \(E_{\text{matrix}}\) and \(\nu_{\text{matrix}}\) are defined as described above and \(\beta\) represents the exponential stiffening coefficient (Eqs. 3–5) (Holmes and Mow 1990; Maas et al. 2012). The power-linear fiber description described AF nonlinearity and anisotropy, where \(\gamma\) represents the power-law exponent in the toe region, \(E_{{{\text{lin}}.}}\) represents the fiber modulus in the linear region and \(\lambda_{0}\) represents the transition stretch between the toe and linear region (Eq. 6). Parameter \(B\) is described as a function of \(\gamma\), \(E_{{{\text{lin}}.}}\), and \(\lambda_{0}\) (\(B = \frac{{E_{{{\text{lin}}.}} }}{2}\left( {\frac{{\left( {\lambda_{0}^{2} - 1} \right)}}{{2\left( {\gamma - 1} \right)}} + \lambda_{0}^{2} } \right)\)). Lastly, fibers were described as being active only in tension:

For FEMs that employed homogenization theory (HOM), a compressible hyperelastic Holmes–Mow material description was used to describe the ground matrix substance. Similar to SEP models, AF nonlinearity and anisotropy were incorporated by embedding a fiber description within the matrix. Fibers were described using a power-linear stress–strain relationship. Strain energy density functions for the ground matrix substance and fibers were identical to those used in the SEP models (Eqs. 3–6).

2.2 Multiscale model calibration and validation framework

A multiscale framework was applied during model calibration and validation. First, single-lamellar SEP and HOM models were developed, and model parameters were calibrated to experimental data from single-lamellar uniaxial tensile tests both along and transverse to the fiber direction (experimental data from ventrolateral external AF; Fig. 1c) (Holzapfel et al. 2005). Model calibration was conducted until the computational Young’s modulus for both model types in the low-, medium-, and high-stress regions was within 10% of experimental data (Fig. 1c—stress–strain curves; Table 1). Calibrated model parameters that can be directly linked to tissue physical properties were also compared to data in the literature. Then, model validation was performed by predicting multiaxial bulk tissue mechanics using multi-lamellar specimens (Fig. 1d). For each SEP model, an HOM model with identical specimen length, width, and thickness was developed. As the more commonly used modeling approach, the validation results of the HOM models were considered as a baseline for comparison with SEP models.

Model robustness was evaluated by simulating a range of reported loading modalities and boundary conditions. Simulated loading modalities included uniaxial tension along the circumferential and axial directions (Fig. 2a), biaxial tension in the circumferential–axial plane (Fig. 2b), and simple shear along the circumferential and axial directions (Fig. 2c). Three boundary conditions were evaluated, based on differences in reported gripping methods (gripped, vertebrae-attached, and parallel-plate, Fig. 2). The gripped boundary condition represented sandpaper glued to specimens and used to interface with testing equipment (Acaroglu et al. 1995; Elliott and Setton 2001; Guerin and Elliott 2006; O’Connell et al. 2009, 2012). The vertebrae-attached boundary condition referred to the case where tissue testing was prepared with the adjacent vertebrae attached to the AF and used to interface with test equipment (Green et al. 1993; Żak and Pezowicz 2016). The parallel-plate boundary condition described the case where specimens were clamped between polystyrene parallel plates for simple shear testing (Fujita et al. 2000).

Each validation model was loaded in a two-step process. Free swelling in 0.15 M phosphate-buffered saline was simulated prior to mechanical loading to account for specimen hydration. For uniaxial tension, a 20% engineering strain was applied. For biaxial tension, corresponding strain was applied in the circumferential and axial directions to represent the relative strain ratios reported in the literature [circumferential/axial strain ratios = 1:1 (equibiaxial) and 1:0 (axial-fixed)]. The simulation for biaxial tension was terminated when strain in either direction reached 15%. For simple shear, a 10% shear strain was applied in either circumferential or axial direction. Linear-region, apparent, or shear modulus was calculated as the slope of the corresponding stress–strain curve in the linear region and compared to values reported in the literature. Valid SEP or HOM model predictions of multi-lamellar mechanics were defined as predicted bulk modulus being within one standard deviation of reported mean values (Green et al. 1993; Acaroglu et al. 1995; Fujita et al. 2000; Elliott and Setton 2001; Guerin and Elliott 2006; O’Connell et al. 2009; Żak and Pezowicz 2016).

For a more rigorous validation, an exhaustive set of literature data was included for each loading modality and boundary condition (Table 2). Studies that conducted tissue-level tests using multi-lamellar specimens obtained from anterior middle-outer healthy human AF qualified for validation tests as long as relevant experimental protocols including tissue hydration, specimen orientation, and boundary and loading condition applied, were explicitly reported. Data from Green et al. 1993 were included despite the relatively high strain rate used, because it has been observed that modulus was not rate dependent when low to medium strain rates were applied (i.e., < 0.5 s−1) (Green et al. 1993; Kasra et al. 2004). Mean and standard deviations for moduli were pooled across studies by calculating the weighted average of mean or standard deviations (\(E_{\text{pooled}} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{s} n_{i} E_{i} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{s} n_{i} }}\), \({\text{SD}}_{\text{pooled}} = \frac{{\sqrt {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{s} n_{i} {\text{SD}}_{i}^{2} } }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{s} n_{i} - s}}\), where s represents total number of studies included, n represents study-specific sample size, and Ei and SDi represent the mean and standard deviation of the modulus reported in each study).

2.3 Effect of specimen geometry on tensile mechanics

Following model validation, the effect of specimen geometry on AF bulk mechanics was investigated, because experimental observations noted that modulus was sensitive to specimen geometry (Adams and Green 1993; Lechner et al. 2000; Werbner et al. 2017). Additional uniaxial multi-lamellar SEP models were created along the circumferential direction (n = 50 models; Fig. 1a). Specimen geometry for length was varied between 6 and 15 mm in 1 mm increments, and width was varied between 2 and 3 mm in 0.25 mm increments, resulting in length-to-width aspect ratios (AR) between 2.0 and 7.5. Uniaxial tension was applied as described above, and the predicted linear-region modulus was calculated. During loading, specimen top and bottom surfaces were constrained to restrict displacement in the loading direction.

A multivariate linear regression model was used to characterize the relationship between bulk tissue modulus (y) and specimen geometry (\(x_{1}\): length; \(x_{2}\): 1/width; Eq. 7; R software, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). In Eq. 7, \(\beta_{i}\) represent regression parameters, which were determined using the least squares method, and \(\varepsilon\) represents errors in the statistical model. The effect of specimen width was represented as 1/width to incorporate aspect ratio as an interaction term (i.e., length/width or \(x_{1} x_{2}\)). If a parameter, \(\beta_{i}\), was determined to be statistically insignificant, it was removed from the model and the analysis was repeated with the reduced linear regression model. Significance was assumed for p values ≤ 0.05. The relative contribution of specimen length, width, and aspect ratio to AF tensile modulus was calculated using the relaimpo package and reported as a percent (Grömping 2006).

3 Results

3.1 Multiscale model calibration and validation

Our preliminary work showed that SEP model-predicted bulk tissue modulus was consistent for models with three or more lamellae (Fig. 3), while HOM model-predicted bulk tissue modulus was not affected by specimen thickness (Fig. 3a—overlapping dashed lines). Based on these findings, multi-lamellar models of both model types were developed with three layers for computational efficiency.

Stress–strain curves from calibrated single-lamellar HOM and SEP models were nonlinear, agreeing well with the literature (Fig. 1c). For both model types, computational modulus for the low-, medium-, and high-stress regions of the stress–strain curve also matched values in the literature (Table 1). Calibrated model parameters for both model types are summarized in Table 3; parameters that can be linked to tissue physical properties also had values that agreed well with reported values (Table 3; Fig. 4—parameter values were within one standard deviation of reported means).

A summary of model validation results is provided in Table 4. Simulations of uniaxial tensile tests along the circumferential direction were all subjected to the gripped boundary condition (four models; Fig. 5a—inset). Multi-lamellar SEP and HOM models both demonstrated a nonlinear stress–strain response (Fig. 5a; Table 4—‘Lin.’). The circumferential-direction toe-region modulus was ~ 4 MPa for both SEP and HOM model types and was within one standard deviation of reported values (pooled experimental toe-region modulus = 2.6 ± 2.1 MPa) (Elliott and Setton 2001; Guerin and Elliott 2006; O’Connell et al. 2009). However, at greater strains, there was a large deviation in predicted behavior by SEP and HOM models (Fig. 5a). SEP-predicted linear-region modulus was within the range of reported values (< 0.9× standard deviation from the reported mean; Fig. 5b—white versus black bars) (Acaroglu et al. 1995; Elliott and Setton 2001; Guerin and Elliott 2006; O’Connell et al. 2009). In contrast, HOM models overestimated the linear-region modulus by 120–600% (> 2× standard deviations from the reported mean; Fig. 5b—white versus gray bars).

Four model simulations were performed to evaluate SEP and HOM models response under uniaxial tension in the axial direction (Fig. 6). Two model simulations were subjected to the vertebrae-attached boundary condition (Fig. 6a—inset), and two model simulations were subjected to the gripped boundary condition (Fig. 6c—inset). For the vertebrae-attached specimens, multi-lamellar SEP and HOM models both demonstrated a nonlinear stress–strain response (Fig. 6a). Similar to results for uniaxial tension along the circumferential direction, SEP and HOM model predictions for toe-region modulus were comparable to each other and agreed with data in the literature (~ 2.5 MPa), while differences in tissue mechanics predicted by the two model types were more pronounced at larger strains (i.e., HOM models predicted greater stresses in the linear region). SEP-predicted linear-region modulus was within 15% of the reported mean value (< 0.26× standard deviation away from the reported mean; Fig. 6b). However, HOM models predicted a linear-region modulus that was at least 150% greater than reported values (> 2.5× standard deviation away from the reported mean; Fig. 6b) (Green et al. 1993; Żak and Pezowicz 2016). For the gripped specimens, SEP and HOM models both generated a similar pseudo-linear stress–strain curve (Fig. 6c) and accurately predicted the tensile modulus reported by Elliott and Setton (2001) (< 0.2× standard deviation from the reported mean; Fig. 6d). Model validation to data reported in O’Connell et al. (2009) resulted in an overestimation of the axial-direction tensile modulus, but the predicted modulus from both model types was on the same order of magnitude as the reported mean (SEP: overestimated modulus by ~ 45% or 1.7× standard deviations from the reported mean, HOM: overestimated modulus by ~ 60% or 2.4× standard deviations from the reported mean; Fig. 6d) (O’Connell et al. 2009).

a, c Representative stress–strain response from SEP and HOM models under uniaxial tension (axial direction). Evaluated boundary conditions included a vertebrae-attached and c gripped. Model-predicted linear-region modulus compared to corresponding experimental (EXP) data that used b vertebrae-attached or d gripped boundary conditions

Three model simulations were performed to evaluate SEP and HOM models response under biaxial tension. All model simulations were subjected to the gripped boundary condition (Fig. 7a to c—inset). Experimental average and standard deviation for apparent modulus were not reported; therefore, validations were performed using the representative stress–strain curve reported by O’Connell et al. (2012). In all validation cases, SEP and HOM models demonstrated a nonlinear and pseudo-linear stress–strain behavior, respectively (Fig. 7 a to c—black solid versus grey dashed curves). Under equibiaxial tension, SEP models accurately predicted the apparent modulus while HOM models underestimated the apparent modulus by ~ 45% in the circumferential direction (Fig. 7d—Equibiax., Ecirc.); in the axial direction, SEP and HOM models underestimated the apparent modulus by ~ 30% and ~ 70%, respectively (Fig. 7d—Equibiax., Eax.). Under the axial-fixed condition, SEP and HOM models underestimated the circumferential-direction apparent modulus by ~ 20% and ~ 60%, respectively (Fig. 7d—Ax.-fixed, Ecirc.).

Stress–strain response from SEP and HOM models in the a circumferential and b axial directions under equibiaxial (equibiax.) tension. c Circumferential-direction stress–strain response from SEP and HOM models under the axial-fixed (ax.-fixed) loading condition. d Model-predicted apparent modulus compared to experimental data (EXP) reported in O’Connell et al. (2012)

Two model simulations were performed to evaluate SEP and HOM models response under simple shear. Both model simulations were subjected to the parallel-plate boundary condition (Fig. 8a, b—inset). In the circumferential direction, SEP and HOM models both predicted a pseudo-linear stress–strain response (Fig. 8a). The SEP-predicted shear modulus was ~ 160 kPa and matched well with reported values (< 0.93× standard deviation from the reported mean), while the HOM-predicted modulus was greater than 300 kPa or more than 200% greater than the reported mean (> 3.8× standard deviations from the reported mean; Fig. 8c) (Fujita et al. 2000). In the axial direction, SEP and HOM models both predicted a nonlinear stress–strain response (Fig. 8b), and both models greatly overestimated the axial-direction shear modulus (SEP: overestimated modulus by ~ 500% or > 10× standard deviations from the reported mean; HOM: overestimated by ~ 660% or > 13× standard deviations from the reported mean; Fig. 8c) (Fujita et al. 2000).

3.2 Effect of specimen geometry on tensile modulus

After validation, the SEP model was used to study the effect of specimen geometry on bulk tissue modulus. A nonlinear decrease in AF tensile modulus was observed with an increase in specimen length (Fig. 9a). Based on this response, a logarithmic transformation was performed to determine the relationship between specimen geometry and bulk modulus with a multivariate linear regression. AF tensile modulus increased linearly with specimen width, and the rate of change in tensile modulus with specimen width was dependent on specimen length (Fig. 9b—slopewidth = 7 mm ≈ 1.8 × slopewidth = 15 mm). This finding highlights the dependence of AF tensile modulus on the interaction between specimen length and width (i.e., aspect ratio), where tensile modulus decreased with an increase in aspect ratio (Fig. 9c). Moreover, it appeared that tensile modulus approached a horizontal asymptote as the aspect ratio exceeded 4.0 (ASTM guidelines for uniaxial test specimens (ASTM 2003, 2004); Fig. 9c—gray dots). Therefore, AF tensile modulus was a function of specimen length, width, and aspect ratio (Eq. 8; Supplementary Table). Lastly, based on the relative contribution analysis, AF tensile modulus was most sensitive to specimen width (48% contribution), followed by aspect ratio (36% contribution), and specimen length (16% contribution).

a Model-predicted tensile modulus with respect to specimen length for five specimen widths. b Modulus with respect to specimen width for five specimen lengths (specimens with even-value lengths followed a similar trend but were omitted in the figure for clarity); c Modulus with respect to specimen aspect ratio (AR)

4 Discussion

It is common for model parameter calibrations to be performed at the same scale as the study of interest in both constitutive and finite element modeling studies. For example, to study bulk tissue mechanics, model calibration would be conducted based on multi-lamellar test data from a dataset obtained from a single loading modality, often limiting the model’s ability to accurately predict tissue mechanics under other loading modalities (Bass et al. 2004). Moreover, findings from this study and experimental observations suggest that this curve-fitting approach is limited to specimens with a specific geometry constrained by a particular boundary condition, further restricting the predictive power and the robustness of the model (Adams and Green 1993; Sun et al. 2005; Jacobs et al. 2013; Werbner et al. 2017). Additionally, while these models are widely used to understand contributions of sub-tissue properties to bulk tissue mechanics, it has been difficult to establish relationships between model parameters and tissue physical properties (e.g., collagen stiffness) or biochemical compositions (e.g., cross-links) as model parameters can be nonunique and are purely mathematical coefficients without physical significance (Yin and Elliott 2005; Eskandari et al. 2019).

To address these limitations, we employed a unique multiscale framework for model calibration and validation in this study. Specifically, for both SEP and HOM model types, we considered multi-lamellar AF as a superposition of individual lamellae, which represented the fundamental structural unit (Holzapfel et al. 2005). While model calibration was performed at the sub-tissue scale using single-lamellar experimental data, model validation was performed at bulk tissue scale by predicting multiaxial mechanics using multi-lamellar models. This more rigorous approach ensured the accuracy and robustness of the model, if validated, such that the SEP model can be used to investigate tissue-level mechanics under multiple loading configurations and to understand the role of sub-tissue properties on tissue-level mechanics. Additionally, when developing SEP models, individual AF lamellae were modeled structure-based using known anatomical measurements, resulting in multi-lamellar models with a fibrous network that better resembled the native tissue.

The parameter calibration of single-lamellar SEP and HOM models resulted in a similar stress–strain response with almost identical computational moduli, suggesting that SEP and HOM models may predict similar mechanical behaviors for multi-lamellar specimens if the two modeling approaches shared a comparable accuracy and robustness. However, the SEP model type was rigorously validated (i.e., accurately predicted bulk tissue stress–strain response and corresponding moduli) in ten of 13 validation cases (> 75% passing rate), while the HOM model type was only validated in one validation case, proving the SEP model as a more accurate and robust modeling approach. Although the SEP model slightly overestimated the uniaxial tensile modulus in the axial direction as reported in O’Connell et al. (2009), we considered the SEP model prediction as acceptable, due to the relatively small difference in absolute values (difference between model-predicted modulus and experimental data = 0.19 MPa). Additionally, since only one representative stress–strain curve could be used for each biaxial tension validation case, it is also possible that the SEP model may be acceptable for describing axial-direction mechanics under equibiaxial loading (prediction was within 30% of the reported data) (O’Connell et al. 2012). However, it should be noted that the SEP model greatly overestimated the axial-direction shear modulus, which may be due to fibers being described as continuous bundles, resulting in an increased tissue stiffness due to the immediate engagement of the fiber bundles that extended between the parallel plates after the applied loading (Szczesny et al. 2015, 2017).

Attributed to the multiscale calibration framework, the majority of SEP model parameters (six of eight parameters) could be directly linked to tissue physical properties. The parameters included modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the ground matrix substance (Ematrix, νmatrix), collagen fiber modulus (Elin.), and transition strain (\(\lambda_{0}\)). Additionally, all calibrated values agreed well with reported values (Table 2 and Fig. 4) (Fujita et al. 1997; Elliott and Setton 2001; Holzapfel et al. 2005; Van der Rijt et al. 2006; Shen et al. 2008; Cao et al. 2009; O’Connell et al. 2009). This suggests that the SEP model parameters represent intrinsic tissue properties, broadening the model’s ability to study the effect of degeneration, disease, or injury on tissue mechanics. Particularly, the effect of tissue degeneration and regeneration can be investigated by adjusting fixed charge density of the extrafibrillar matrix, which is indicative to tissue degeneration in native tissues or tissue growth in engineered constructs (Adams and Roughley 2006; Nerurkar et al. 2007). The effect of disease can be investigated by varying fiber modulus, which has been shown to increase with greater fiber cross-linking with diabetes (Li et al. 2013; Svensson et al. 2018). Lastly, the effect of injury, which has been found to be rate dependent, can be investigated by changing the computational loading rate (Wang et al. 2000; Kasra et al. 2004).

To further demonstrate the predictive power of the SEP model, we evaluated the relationship between specimen geometry and AF tensile modulus, based on experimental observations that reported modulus sensitivity to specimen width (Adams and Green 1993; Werbner et al. 2017). A multivariate linear regression model was used to characterize AF tensile modulus as a function of specimen geometry, where specimen length and width were investigated as main factors and aspect ratio was evaluated as an interaction term. The regression analysis suggested that AF tensile modulus was a function of specimen length, width, and aspect ratio. Specifically, AF tensile modulus increased with specimen width and decreased with specimen length and aspect ratio, with specimen width being the most dominant factor. Therefore, unlike traditional engineering materials, AF tensile modulus may not be considered an intrinsic material property due the composite heterogeneous structure of the tissue, and it may be necessary to account for differences in specimen geometry when comparing data across studies. Our findings also suggest that obtaining consistent bulk tissue properties along the circumferential direction may be possible by using specimens with large aspect ratios and a smaller width, which agrees with recent work on meniscus, tendons, and ligaments (Wren et al. 2001; Peloquin et al. 2016; Creechley et al. 2017). Interestingly, Adams and Green (1993) and Werbner et al. (2017) both observed an increase in modulus as the midlength width relative to the grip width decreased. While the midlength-to-grip width ratio was not varied in this study, differences in trends may be due to a difference in fiber engagement, which can be directly evaluated with the SEP model, but not the HOM model.

A few assumptions were made to simplify the current SEP model. First, the fiber network did not include fiber dispersion (Guo et al. 2012), potential fibers in the radial direction (Marchand and Ahmed 1990), variation in fiber diameter or length (Marchand and Ahmed 1990; Han et al. 2012), or fiber–fiber interactions (e.g., cross-links). Particularly, cross-links have been shown to play an important role in tissue subfailure and failure mechanics and will be included in future iterations of the model (Moore et al. 1996; Elliott and Setton 2001; Adams and Roughley 2006; Guerin and Elliott 2006; Provenzano and Vanderby 2006; Roeder et al. 2009; O’Connell et al. 2009; Isaacs et al. 2014). Second, the current model did not investigate different mechanisms for fiber–matrix interactions, which have been suggested to be important for stress distribution during loading (Bruehlmann et al. 2004; Szczesny et al. 2015, 2017; Vergari et al. 2016).

In this study, we developed and validated a multiscale structure-based finite element model that accurately and robustly predicted AF bulk tissue mechanics under multiple loading configurations. Modeling fibers and the extrafibrillar matrix as separate materials, based on the native tissue architecture, resulted in uniquely determined model parameters with physical interpretations. Applying a multiscale framework for model calibration and validation resulted in a rigorous validation process that ensured and improved model accuracy and robustness. In conclusion, the multiscale structure-based modeling approach allows for studies that simultaneously investigate tissue- and sub-tissue-scale mechanics, which will be important for studying multiscale tissue mechanics with degeneration, disease, and injury (Iatridis and Gwynn 2004; Iatridis et al. 2005).

References

Acaroglu ER, Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Mow VC, Weidenbaum M (1995) Degeneration and aging affect the tensile behavior of human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Spine 20(24):2690–2701. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199512150-00010

Adams MA, Green TP (1993) Tensile properties of the annulus fibrosus. Eur Spine J 2(4):203–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00299447

Adams MA, Roughley PJ (2006) What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it? Spine 31(18):2151–2161. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c

Antoniou J, Steffen T, Nelson F, Winterbottom N, Hollander AP, Poole RA, Aebi M, Alini M (1996) The human lumbar intervertebral disc: evidence for changes in the biosynthesis and denaturation of the extracellular matrix with growth, maturation, ageing, and degeneration. J Clin Investig 98(4):996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI11884

ASTM (2003) Standard test method for tensile properties of plastics. ASTM International, West Conshohocken (Standard No. ASTM D638-14)

ASTM (2004) Standard test methods for tension testing of metallic materials. ASTM, West Conshohocken (Standard No. ASTM E8/E8M-13)

Ateshian GA, Chahine NO, Basalo IM, Hung CT (2004) The correspondence between equilibrium biphasic and triphasic material properties in mixture models of articular cartilage. J Biomech 37(3):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00252-5

Bass EC, Ashford FA, Segal MR, Lotz JC (2004) Biaxial testing of human annulus fibrosus and its implications for a constitutive formulation. Ann Biomed Eng 32(9):1231–1242. https://doi.org/10.1114/B:ABME.0000039357.70905.94

Beckstein JC, Sen S, Schaer TP, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM (2008) Comparison of animal discs used in disc research to human lumbar disc: axial compression mechanics and glycosaminoglycan content. Spine 33(6):E166–E173. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318166e001

Benjamin M, Ralphs JR (1997) Tendons and ligaments-an overview. Histol Histopathol 12(4):1135–1144

Bensoussan A, Lions JL, Papanicolaou G (1978) Asymptotic analysis for periodic structures. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Bonet J, Wood RD (1997) Nonlinear continuum mechanics for finite element analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bruehlmann SB, Matyas JR, Duncan NA (2004) ISSLS prize winner: collagen fibril sliding governs cell mechanics in the anulus fibrosus: an in situ confocal microscopy study of bovine discs. Spine 29(23):2612–2620. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000146465.05972.56

Cao L, Guilak F, Setton LA (2009) Pericellular matrix mechanics in the anulus fibrosus predicted by a three-dimensional finite element model and in situ morphology. Cell Mol Bioeng 2(3):306–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12195-009-0081-7

Cassidy JJ, Hiltner A, Baer E (1989) Hierarchical structure of the intervertebral disc. Connect Tissue Res 23(1):75–88. https://doi.org/10.3109/03008208909103905

Cortes DH, Jacobs NT, DeLucca JF, Elliott DM (2014) Elastic, permeability and swelling properties of human intervertebral disc tissues: a benchmark for tissue engineering. J Biomech 47(9):2088–2094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.12.021

Cotta-Pereira G, Rodrigo G, Bittencourt-Sampaio S (1976) Oxytalan, elaunin, and elastic fibers in the human skin. J Investig Dermatol 66(3):143–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1523-1747.ep12481882

Creechley JJ, Krentz ME, Lujan TJ (2017) Fatigue life of bovine meniscus under longitudinal and transverse tensile loading. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 69:185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.12.020

Eberlein R, Holzapfel GA, Schulze-Bauer CAJ (2001) An anisotropic model for annulus tissue and enhanced finite element analyses of intact lumbar disc bodies. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng 4(3):209–229

Elliott DM, Setton LA (2001) Anisotropic and inhomogeneous tensile behavior of the human anulus fibrosus: experimental measurement and material model predictions. J Biomech Eng 123(3):256–263. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1374202

Erwin WM, Hood KE (2014) The cellular and molecular biology of the intervertebral disc: a clinician’s primer. J Can Chiropr Assoc 58(3):246

Eskandari M, Nordgren TM, O’Connell GD (2019) Mechanics of pulmonary airways: linking structure to function through constitutive modeling, biochemistry, and histology. Acta Biomater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2019.07.020

Fujita Y, Duncan NA, Lotz JC (1997) Radial tensile properties of the lumbar annulus fibrosus are site and degeneration dependent. J Orthop Res 15(6):814–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.1100150605

Fujita Y, Wagner DR, Biviji AA, Duncan NA, Lotz JC (2000) Anisotropic shear behavior of the annulus fibrosus: effect of harvest site and tissue prestrain. Med Eng Phys 22(5):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4533(00)00053-9

Goel VK, Monroe BT, Gilbertson LG, Brinckmann P (1995) Interlaminar shear stresses and laminae separation in a disc: finite element analysis of the L3–L4 motion segment subjected to axial compressive loads. Spine 20(6):689–698. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199503150-00010

Green TP, Adams MA, Dolan P (1993) Tensile properties of the annulus fibrosus. Eur Spine J 2(4):209–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00299448

Grömping U (2006) Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo. J Stat Softw 17(1):1–27

Gu WY, Mao XG, Foster RJ, Weidenbaum M, Mow VC, Rawlins BA (1999) The anisotropic hydraulic permeability of human lumbar anulus fibrosus: influence of age, degeneration, direction, and water content. Spine 24(23):2449. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199912010-00005

Gu WY, Yao H, Vega AL, Flagler D (2004) Diffusivity of ions in agarose gels and intervertebral disc: effect of porosity. Ann Biomed Eng 32(12):1710–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-004-7823-4

Guerin HL, Elliott DM (2006) Degeneration affects the fiber reorientation of human annulus fibrosus under tensile load. J Biomech 39(8):1410–1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.007

Guerin HL, Elliott DM (2007) Quantifying the contributions of structure to annulus fibrosus mechanical function using a nonlinear, anisotropic, hyperelastic model. J Orthop Res 25(4):508–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20324

Guo Z, Shi X, Peng X, Caner F (2012) Fibre-matrix interaction in the human annulus fibrosus. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 5(1):193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.05.041

Han WM, Nerurkar NL, Smith LJ, Jacobs NT, Mauck RL, Elliott DM (2012) Multi-scale structural and tensile mechanical response of annulus fibrosus to osmotic loading. Ann Biomed Eng 40(7):1610–1621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-012-0525-4

Holmes MH, Mow VC (1990) The nonlinear characteristics of soft gels and hydrated connective tissues in ultrafiltration. J Biomech 23(11):1145–1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(90)90007-P

Holzapfel GA, Gasser TC, Ogden RW (2000) A new constitutive framework for arterial wall mechanics and a comparative study of material models. J Elast Phys Sci Solids 61(1–3):1–48. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010835316564

Holzapfel GA, Schulze-Bauer CAJ, Feigl G, Regitnig P (2005) Single lamellar mechanics of the human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 3(3):125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-004-0053-8

Huyghe JM, Houben GB, Drost MR, Van Donkelaar CC (2003) An ionised/non-ionised dual porosity model of intervertebral disc tissue. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2(1):3–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-002-0023-y

Iatridis JC, Gwynn I (2004) Mechanisms for mechanical damage in the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus. J Biomech 37(8):1165–1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.026

Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Rawlins BA, Weidenbaum M, Mow VC (1998) Degeneration affects the anisotropic and nonlinear behaviors of human anulus fibrosus in compression. J Biomech 31(6):535–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00046-3

Iatridis JC, MacLean JJ, Ryan DA (2005) Mechanical damage to the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus subjected to tensile loading. J Biomech 38(3):557–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.038

Isaacs JL, Vresilovic E, Sarkar S, Marcolongo M (2014) Role of biomolecules on annulus fibrosus micromechanics: effect of enzymatic digestion on elastic and failure properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 40:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.08.012

Jacobs NT, Cortes DH, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM (2013) Biaxial tension of fibrous tissue: using finite element methods to address experimental challenges arising from boundary conditions and anisotropy. J Biomech Eng 135(2):021004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4023503

Jones RM (1999) Mechanics of composite materials, 2nd edn. Taylor and Francis, London

Juvela S, Porras M, Poussa K (2000) Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg 93(3):379–387. https://doi.org/10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/1052

Kasra M, Parnianpour M, Shirazi-Adl A, Wang JL, Grynpas MD (2004) Effect of strain rate on tensile properties of sheep disc anulus fibrosus. Technol Health Care 12(4):333–342

Klisch SM, Lotz JC (1999) Application of a fiber-reinforced continuum theory to multiple deformations of the annulus fibrosus. J Biomech 32(10):1027–1036

Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC (1991) A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng 113(3):245–258. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2894880

Lechner K, Hull ML, Howell SM (2000) Is the circumferential tensile modulus within a human medial meniscus affected by the test sample location and cross-sectional area? J Orthop Res 18(6):945–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.1100180614

Li Y, Fessel G, Georgiadis M, Snedeker JG (2013) Advanced glycation end-products diminish tendon collagen fiber sliding. Matrix Biol 32(3–4):169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2013.01.003

Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA (2012) FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J Biomech Eng 134(1):011005. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4005694

Marchand FR, Ahmed AM (1990) Investigation of the laminate structure of lumbar disc anulus fibrosus. Spine 15(5):402–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199005000-00011

Michalek AJ, Buckley MR, Bonassar LJ, Cohen I, Iatridis JC (2009) Measurement of local strains in intervertebral disc anulus fibrosus tissue under dynamic shear: contributions of matrix fiber orientation and elastin content. J Biomech 42(14):2279–2285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.06.047

Moore RJ, Vernon-Roberts B, Fraser RD, Osti OL, Schembri M (1996) The origin and fate of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc tissue. Spine 21(18):2149–2155. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199609150-00018

Mow VC, Holmes MH, Lai WM (1984) Fluid transport and mechanical properties of articular cartilage: a review. J Biomech 17(5):377–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(84)90031-9

Nerurkar NL, Elliott DM, Mauck RL (2007) Mechanics of oriented electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for annulus fibrosus tissue engineering. J Orthop Res 25(8):1018–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20384

Nerurkar NL, Mauck RL, Elliott DM (2008) Integrating theoretical and experimental methods for functional tissue engineering of the annulus fibrosus. Spine 33(25):2691. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818e61f7

Nerurkar NL, Mauck RL, Elliott DM (2011) Modeling interlamellar interactions in angle-ply biologic laminates for annulus fibrosus tissue engineering. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 10(6):973–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-011-0288-0

O’Connell GD, Guerin HL, Elliott DM (2009) Theoretical and uniaxial experimental evaluation of human annulus fibrosus degeneration. J Biomech Eng 131(11):111007. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3212104

O’Connell GD, Jacobs NT, Sen S, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM (2011) Axial creep loading and unloaded recovery of the human intervertebral disc and the effect of degeneration. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 4(7):933–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.02.002

O’Connell GD, Sen S, Elliott DM (2012) Human annulus fibrosus material properties from biaxial testing and constitutive modeling are altered with degeneration. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 11(3–4):493–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-011-0328-9

O’Connell GD, Leach JK, Klineberg EO (2015) Tissue engineering a biological repair strategy for lumbar disc herniation. Biores Open Access 4(1):431–445. https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2015.0034

Partanen JI, Partanen LJ, Vahteristo KP (2017) Traceable thermodynamic quantities for dilute aqueous sodium chloride solutions at temperatures from (0 to 80) C. Part 1. Activity coefficient, osmotic coefficient, and the quantities associated with the partial molar enthalpy. J Chem Eng Data 62(9):2617–2632. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jced.7b00091

Peloquin JM, Santare MH, Elliott DM (2016) Advances in quantification of meniscus tensile mechanics including nonlinearity, yield, and failure. J Biomech Eng 138(2):021002. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4032354

Peng XQ, Guo ZY, Moran B (2006) An anisotropic hyperelastic constitutive model with fiber-matrix shear interaction for the human annulus fibrosus. J Appl Mech 73(5):815–824. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2069987

Provenzano PP, Vanderby R Jr (2006) Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol 25(2):71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2005.09.005

Robinson RA, Stokes RH (1949) Tables of osmotic and activity coefficients of electrolytes in aqueous solution at 25 C. Trans Faraday Soc 45:612–624. https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9494500612

Roeder BA, Kokini K, Voytik-Harbin SL (2009) Fibril microstructure affects strain transmission within collagen extracellular matrices. J Biomech Eng 131(3):031004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3005331

Rubin DI (2007) Epidemiology and risk factors for spine pain. Neurol Clin 25(2):353–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.004

Sanchez-Palencia E, Zaoui A (1987) Homogenization techniques for composite media. Springer, Berlin

Schmidt H, Heuer F, Simon U, Kettler A, Rohlmann A, Claes L, Wilke HJ (2006) Application of a new calibration method for a three-dimensional finite element model of a human lumbar annulus fibrosus. Clin Biomech 21(4):337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.12.001

Schmidt H, Heuer F, Drumm J, Klezl Z, Claes L, Wilke HJ (2007) Application of a calibration method provides more realistic results for a finite element model of a lumbar spinal segment. Clin Biomech 22(4):377–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.11.008

Schollum ML, Robertson PA, Broom ND (2010) How age influences unravelling morphology of annular lamellae—a study of interfibre cohesivity in the lumbar disc. J Anat 216(3):310–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01197.x

Shen ZL, Dodge MR, Kahn H, Ballarini R, Eppell SJ (2008) Stress–strain experiments on individual collagen fibrils. Biophys J 95(8):3956–3963. https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.107.124602

Shirazi-Adl SA, Shrivastava SC, Ahmed AM (1984) Stress analysis of the lumbar disc-body unit in compression. A three-dimensional nonlinear finite element study. Spine 9(2):120–134. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-198403000-00003

Spencer AJM (1984) Continuum theory of the mechanics of fibre-reinforced composites. Springer, New York

Sun W, Sacks MS, Scott MJ (2005) Effects of boundary conditions on the estimation of the planar biaxial mechanical properties of soft tissues. J Biomech Eng 127(4):709–715. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1933931

Svensson RB, Smith ST, Moyer PJ, Magnusson SP (2018) Effects of maturation and advanced glycation on tensile mechanics of collagen fibrils from rat tail and Achilles tendons. Acta Biomater 70:270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.02.005

Szczesny SE, Caplan JL, Pedersen P, Elliott DM (2015) Quantification of interfibrillar shear stress in aligned soft collagenous tissues via notch tension testing. Sci Rep 5:14649. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14649

Szczesny SE, Fetchko KL, Dodge GR, Elliott DM (2017) Evidence that interfibrillar load transfer in tendon is supported by small diameter fibrils and not extrafibrillar tissue components. J Orthop Res 35(10):2127–2134. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23517

Urban JPG, Maroudas A (1979) The measurement of fixed charged density in the intervertebral disc. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Gen Subj 586(1):166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4165(79)90415-X

Van Der Rijt JA, Van Der Werf KO, Bennink ML, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J (2006) Micromechanical testing of individual collagen fibrils. Macromol Biosci 6(9):697–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.200600063

Vergari C, Mansfield J, Meakin JR, Winlove PC (2016) Lamellar and fibre bundle mechanics of the annulus fibrosus in bovine intervertebral disc. Acta Biomater 37:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.04.002

Wagner DR, Lotz JC (2004) Theoretical model and experimental results for the nonlinear elastic behavior of human annulus fibrosus. J Orthop Res 22(4):901–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthres.2003.12.012

Wagner DR, Reiser KM, Lotz JC (2006) Glycation increases human annulus fibrosus stiffness in both experimental measurements and theoretical predictions. J Biomech 39(6):1021–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.013

Wang JL, Parnianpour M, Shirazi-Adl A, Engin AE (2000) Viscoelastic finite-element analysis of a lumbar motion segment in combined compression and sagittal flexion: effect of loading rate. Spine 25(3):310–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200002010-00009

Werbner B, Zhou M, O’Connell GD (2017) A novel method for repeatable failure testing of annulus fibrosus. J Biomech Eng 139(11):111001. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4037855

Wren TA, Yerby SA, BeauprÈ GS, Carter DR (2001) Mechanical properties of the human achilles tendon. Clin Biomech 16(3):245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(00)00089-9

Wu HC, Yao RF (1976) Mechanical behavior of the human annulus fibrosus. J Biomech 9(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(76)90132-9

Yang B, O’Connell GD (2019) Intervertebral disc swelling maintains strain homeostasis throughout the annulus fibrosus: a finite element analysis of healthy and degenerated discs. Acta Biomater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2019.09.035

Yin L, Elliott DM (2005) A homogenization model of the annulus fibrosus. J Biomech 38(8):1674–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.07.017

Żak M, Pezowicz C (2013) Spinal sections and regional variations in the mechanical properties of the annulus fibrosus subjected to tensile loading. Acta Bioeng Biomech. https://doi.org/10.5277/abb130107

Żak M, Pezowicz C (2016) Analysis of the impact of the course of hydration on the mechanical properties of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc. Eur Spine J 25(9):2681–2690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4704-0

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by National Science Foundation (Grant No. 1760467).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Bezci, S.E. & O’Connell, G.D. Multiscale composite model of fiber-reinforced tissues with direct representation of sub-tissue properties. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 19, 745–759 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-019-01246-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-019-01246-x