Abstract

Research suggests that the reported increase in student mental health issues such as study burnout might be related to students’ identity problems and their motivations for undertaking higher education. The present study added to this line of research by investigating the associations between identity profiles, motives for attending university and study burnout in a sample of Finnish first-year university students (N = 430). Field of study (professional vs non-professional) as a factor was also evaluated because differing occupational prospects might influence one’s sense of identity. The results showed that (1) three identity profiles emerged (i.e. achievement, moderate moratorium and diffusion), (2) students in the achievement profile scored lowest on burnout, (3) the achievement profile was the most common among students studying for entry to a profession and (4) students in the achievement profile scored highest on internal motives for attending university. It is concluded that most students lack a clear sense of identity and that identity measures may be more appropriate in predicting study progression and well-being than motives for attending university or engaging in a field of study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Higher education students are suffering from stress, study burnout and mental health problems more than before (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017; Zivin et al., 2009). Based on observations mainly from North America, Côté (2018) has linked this so-called student mental health crisis with current tendencies to psychologize structural changes and challenges in both youth identity formation and higher education. First, identity is today a more prolonged and precarious task than in the past due to new social and economic uncertainties. Second, current social and educational policies that promote massification of education push increasing numbers of uncertain, academically unprepared and extrinsically motivated youth into higher education.

Indeed, earlier research has on the one hand linked adolescents’ identity processes with academic motivation, school experience and study burnout (Erentaitė et al., 2018; Kindelberger et al., 2020). On the other hand, it has linked students’ motives for learning and attending university (e.g. personal-intellectual development vs expectation-driven) with academic achievement, commitment to studying at university and study burnout (Heikkilä et al., 2012; Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012; Korhonen et al., 2019; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). However, there are limited studies examining the interconnections between these factors—identity, motivation, burnout. For one thing, past research has not investigated how identity profiles are linked with motives and burnout. A related interesting question is whether there are differences between students in different fields of study (professional vs non-professional) as the different occupational prospects (i.e. clarity in career path and outcomes) should affect one’s sense of identity. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on these questions in the European and especially the Nordic context. Thus, the purpose of this study was to expand research on the link between identity, motivation and burnout by investigating how identity profiles (Luyckx et al., 2008; used synonymously with statuses in what follows) of Finnish first-year university students are associated with motivations for attending university and study burnout, with a focus on possible differences between law students and students within the humanities. By ‘burnout’, we refer to ‘study burnout’ throughout the article, unless stated otherwise.

Structural changes in identity formation and higher education

Identity is a multidimensional concept with slightly diverse uses in different scientific disciplines (McLean & Syed, 2016). However, Erikson (1950, 1968) defined identity formation as building a sense of personal uniqueness and continuity by integrating personal goals, ideals, values and roles into a personally meaningful and coherent picture. Identity is critical for psychological well-being because stability of the self generates predictability and security. A lack of identity, by contrast, entails confusion over direction and purpose in life and leaves one ill prepared to tackle later life challenges. Although Erikson regarded identity as the key developmental task of adolescence, he simultaneously considered it to be a life-long, ceaseless process towards stability.

A widely shared view in youth studies today is that youths’ lives and individual experiences have become precarized and planning ahead is increasingly difficult (e.g. Carmo et al., 2014; Furlong et al., 2016; Leccardi, 2005). Economic uncertainty and a societal ethos of individual success and responsibility (e.g. the entrepreneurial self; Furlong & Cartmel, 2009) require individuals to shift attention and commitments continually to secure recognition and admiration. As the outcomes and prospects of one’s choices become increasingly diffuse, decision-making (and decisiveness) becomes difficult and people end up avoiding firm commitments and ruminating over (un)chosen options. According to Côté (2019), achieving a sense of identity becomes highly challenging in this environment. This trend of uncertainty is observed in youth gap years, prolonging study, postponing entering the labour market and parenthood (through unstable relationships), as well as the prevalence of identity confusion (e.g. Arnett, 2019; Bühler & Nikitin, 2020; Mannerström et al., 2019; Parker et al., 2015).

Moreover, Côté, (2019) ties this general lack of identity among youth to the surge in students’ mental health problems reported in many Western countries, including Finland (Auerbach et al., 2018; FSHS, Finnish Student Health Service, 2016). The psychological problems are largely the outcome of well-meaning social and educational policies pushing increasing numbers of academically uncertain and unfit youths into higher education (i.e. massification of higher education), where they study under great stress for a vague and unstable future labour market (e.g. jobs that do not exist yet). The situation is made worse by the rise of a psychiatric therapeutic narrative in recent decades, which reframes and diagnoses normative identity conflicts of youth as isolated and preferably avoidable anxiety and depression symptoms. The danger of psychologizing structural challenges and labelling individuals with deficits in need of counselling is that these become fixed and integrated parts of the one’s identity, further prolonging the crisis. Thus, according to Côté, (2019), the now widespread experience of challenging studies and mental health issues are a symptom of unresolved identity issues and related poor internal motivation (see also Auerbach et al., 2018). Unfortunately, despite its far-reaching implications for young people’s (worsening) mental health, this identity-motivation-burnout link remains underexplored, especially so in the European and Nordic context. In the next section, we will describe the basis of identity formation measurement in this study, followed by presenting the available research on the relationship between motivations for attending university and burnout.

Measurement of identity formation

Within the Eriksonian research paradigm, identity formation has typically been studied with the two-dimensional identity status model (Marcia, 1966, 1993). By assessing exploration and commitment in different life domains (originally occupation, politics and religion), respondents are assigned an identity status indicating current progress in development. Those in achievement have explored different options and made commitments; those in foreclosure also have commitments but without prior exploration; those in moratorium, in turn, lack commitments but are currently exploring their alternatives; and finally, those in diffusion lack commitments and exploration. Many studies have shown that the statuses differ in personality characteristics, cognitive processes and most notably psychological well-being, with individuals in achievement scoring the highest on self-esteem and lowest on anxiety and those in diffusion or moratorium showing the opposite pattern (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Furthermore, several longitudinal studies have by now shown that identity development, in general, proceeds towards greater integration in adolescence and adulthood. However, the process is slow, stability of the identity status is very common and diverse developmental trajectories also exist (i.e. progression and regression), with often only one status transition taking place over time (e.g. Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Meeus, 2018).

Later, Luyckx and colleagues (2008) extended the identity status model with three processes. First, different identity alternatives are explored (i.e. exploration in breadth) and commitments are formed (i.e. commitment making). Second, these commitments are scrutinized (i.e. exploration in depth) and, based on the evaluation, either strengthened and emotionally identified with (i.e. identification with commitment) or discarded, whereupon exploration starts all over again. A failure to achieve expected (firm) commitments might increase an anxious type of brooding and rumination over alternatives (i.e. ruminative exploration), which further undermines commitments. Rumination is considered to be a core challenge for today’s youth, who face seemingly endless life path and lifestyle options but very diffuse prospects due to increased social (e.g. relationships) and economic (e.g. labour market) uncertainty.

The five processes have been studied with the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS; Luyckx et al., 2008) and typically within the life domain of general future plans. Although ‘general future plans’ may appear diffuse as a life domain, it captures a general sense of direction in life, critical for youth deciding on their education and career (Mannerström et al., 2019; Nurmi, 1991). Studies have shown that identification with commitment and ruminative exploration are most strongly associated with psychological well-being variables such as self-esteem, life satisfaction and depression symptoms (e.g. Mannerström et al., 2017; Sica et al., 2014). By contrast, studies employing cluster analysis or latent profile analysis (LPA) have typically found five or six statuses (e.g. Mannerström et al., 2017; Schwartz et al., 2011), of which four resemble those identified by Marcia: achievement (high scores on the commitment dimensions and exploration in depth, moderate to high scores on exploration in breadth and low scores on ruminative exploration); foreclosure (or early closure; Meeus et al., 2010; high commitment and low exploration); moratorium (low commitment and high exploration); and troubled diffusion (moderate to high scores on ruminative exploration and low scores on the other dimensions). Two additional statuses have been labelled carefree diffusion (similar pattern with troubled diffusion but significantly lower scores on ruminative exploration) and searching moratorium (moderate to high scores on all dimensions). In line with theory, several studies have shown achievement and (early) closure to be the most stable statuses over time, indicating aspired ‘endpoints’ of development (e.g. Meeus, 2018; Meeus et al., 2010), and individuals in these statuses also score the highest on psychological well-being variables such as self-esteem, life satisfaction and meaning in life (e.g. Schwartz et al., 2011). By contrast, diffusion and moratorium statuses typically show the opposite pattern.

Student motivations for attending university

Students applying to enter university are a heterogeneous group and they have diverse reasons for attending university studies. Students’ motives for going to university have been found to be important in relation to students’ academic achievement, such as study success, study progress and commitment to studying at university (Dennis et al., 2005; Korhonen et al., 2019; Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012). Furthermore, motivational aspects of learning are also related to general well-being as well as to burnout and the student’s engagement (Heikkilä et al., 2012; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017).

To identify different motivations, Côté & Levine, (1997, 2000) developed a typology and questionnaire focusing on student motives to attend university studies (SMAU). Five motivation orientations showing internal, external and unclear commitment to university studies were identified. Students with a personal-intellectual motive aim to gain personal growth as well as to understand the complexities of life and the world by studying at university. Students with a careerist-materialist motive perceive studying at university as a means to achieve a better level of status in society, a higher income, career success and the fine things of life. For students with a humanitarian motive, the main concern is with improving the world, and helping those less fortunate in life, and with changing the system to improve society. Students with the expectation-driven motive mainly attend university to respond to expectations and pressures from family and friends to go to university and acquire a degree. Finally, students with a default motive do not exactly know why they are attending university except that doing so is better than pursuing other options (see also Guo et al., 2018).

Studies show that students with personal and intellectual motives to undertake higher education have been found to obtain higher grades than those with other types of motive (Côté & Levine, 1997) and are more engaged with their studying (Dennis et al., 2005; Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012; Korhonen et al., 2019). Personal and career motives have also been found to be positively related to self-efficacy and confidence in the ability to achieve degree goals (Phinney et al., 2006). By contrast, the expectation-driven and default motives have been found to be related to lack of motivation and interest in studying as well as poorer academic adjustment to one’s study programme (Phinney et al., 2006; see also Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012; Baik et al. 2017). Côté & Levine (1997) point out that most students are mixed types who score high on more than one motivation. Only one-third of students may be considered ‘pure’ types representing only one type of motivational dimension.

Although academic motivation has been linked with identity formation, prior research has focused mainly on adolescents and examined associations between more ‘general’ motivations for studying (i.e. autonomous/controlled/impersonal), goal pursuits (intrinsic vs extrinsic), identity commitment and exploration processes (Cannard et al., 2016; Kindelberger et al., 2020; Luyckx et al., 2017) and/or academic identity status (Hejazi et al., 2012). Thus, there is a research gap on links between general identity statuses among students (i.e. how they perceive their future) and various motives for attending university. This would shed more light on the proclaimed identity uncertainty among youth and its relationship with low internal motivation and burnout (Côté, 2019).

Study burnout

Burnout in the university study context can be defined as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion that is an outcome of perceived high demands of studying at university, the development of a cynical and detached attitude to studying at university and feelings of inadequacy as a university student (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). In line with the study demands and resources model (Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2014), a misfit between demands and resources—both study-related and personal—leads to burnout, whereas a good fit leads to engagement. A high level of burnout has been associated with lower internal motivation (i.e. engagement in studying for enjoyment, satisfaction or pleasure), higher amotivation to study (Lyndon et al., 2017) and school and university dropout (Bask & Salmela-Aro, 2013) as well as lower educational aspirations (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017).

There is also some evidence of links between identity formation and burnout. One study by Erentaitė and colleagues (2018) investigated identity styles, a concept related to identity status research but referring to personal ways of dealing with or ‘tackling’ identity conflicts and issues (i.e. socio-cognitive processing such as problem-solving, decision-making). Their longitudinal study on school experience (including burnout) found that burnout predicted both compliance with other people’s expectations (i.e. normative style) and complete avoidance of identity issues (i.e. diffuse-avoidant style). The study shows that burnout is not only a detrimental outcome but it blocks a proactive engagement with identity issues. This may well lead to a vicious circle of a weaker identity, more avoidance of identity issues, less agency and more psychological problems. Another study by Luyckx et al., (2010) examined identity statuses but focused on job burnout among employed 21- to 40-year-olds. In line with expectations, individuals who had thought about various life directions and made autonomous decisions regarding their career (i.e. achievement status) were more strongly invested in their work and they experienced significantly less job burnout than individuals in moratorium and diffusion. The authors concluded that a firm identity—being committed and having a sense of direction in life—brings major resources such as high self-esteem, internal locus of control and self-efficacy, which increase engagement and repel emotional exhaustion. This might also be the case for students. On the other hand, the environment is different for students who are only now studying for a future career. For students, motives for studying and type of education or career prospects might play a role in identity formation.

The present study

Previous literature suggests that students’ stress and burnout symptoms are linked with young people’s prolonged identity troubles and related lack of academic motivation (Côté, 2019). However, knowledge of what identity structures (e.g. achieved vs diffused) young people enter university with, and their interconnections with motives and study burnout, is still missing, especially so in the European and Nordic context.

Furthermore, prior research has not considered the impact of different fields of study on identity and burnout. The focus of the present research was in two distinct fields: law and humanities. The bachelor’s curricula in these two disciplines are different in nature and thus offer interesting opportunities for comparison. Law represents a professional programme which qualifies graduates for a certain profession. The study programme in law is pre-scheduled and structured with few optional courses. In humanities, the bachelor’s programmes are more generalist in nature and do not qualify for a specific profession. Generalist programmes are characterized by academic freedom and there are fewer compulsory elements. Students can freely follow their individual paths both in terms of study pace and selecting course modules and minors. A distinctive feature of the humanities is the lack of clear future goals and open-ended career prospects (Mikkonen et al., 2013). This freedom of choice has been found to pose a challenge to students in terms of the independence required from students (Mikkonen, 2012). It has been suggested that humanities students may prolong their studies due to a fear of unemployment and unclear career opportunities (Mikkonen, 2012) and the graduation times are generally the longest in this field (University student register, 2018). Mikkonen et al. (2013) suggest that exploration of one’s career identity is more common among students in generalist study programmes where future career options are often unclear to the students.

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to shed more light on the proclaimed identity-motivation-burnout link. Specifically, we wanted to know how identity is related to motivation and what role each of these play in burnout and how the field of study might mediate these links. Our research questions were as follows: (1) What identity profiles (i.e. statuses) emerge among first-year university students? (2) How are identity status and motives to attend university associated and what are the links with burnout? (3) Are there any differences between students in professional and non-professional fields in these variables, looking at law and the humanities respectively in this paper?

Hypotheses

-

o

H1: Five or six identity statuses found in previous studies (e.g. Luyckx et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2011) will be identified with the DIDS: achievement, (early) closure, searching moratorium, ruminative moratorium, troubled diffusion and carefree diffusion. Identity statuses were operationalized as profiles, due to the method (i.e. latent profile analysis) used in deriving the statuses.

-

p

H2: High commitment profiles (i.e. achievement, closure) will score low on burnout, whereas low commitment profiles (i.e. ruminative moratorium, troubled diffusion) will score high on burnout. Past literature shows that a firm identity is positively linked with psychological well-being (e.g. Luyckx et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2011).

-

q

H3: High commitment profiles will be more common among law students (professional) and low commitment profiles more common among students in the humanities (non-professional), based on differences in occupational prospects (see above).

-

r

H4: The achievement profile, but not closure, will show higher scores on personal-intellectual development and lower scores on expectation-driven and default motives than low commitment profiles. The opposite pattern is expected with the low commitment profiles. This is because self-regulated identity choices (e.g. in education/career) carry personal meaning and engagement, which other-regulated or externally driven choices do not (e.g. Hejazi et al., 2012).

There were no hypotheses regarding gender or socioeconomic status because they were not measured.

Method

Participants

The participants consisted of 430 first-year students at the University of Helsinki, who completed an electronic questionnaire 2 months after beginning their studies in autumn 2019. Of these students, 250 had started studying humanities, in one of three bachelor’s programmes: art studies (n = 28), history (n = 32) and languages (n = 190). One hundred eighty students were studying law. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines set by APA. However, participation was not voluntary because it was part of an obligatory course with credits. The overall response rate was high (75%) as the questionnaire was included as part of the bachelor’s degree course.

Measures

The data for this study were gathered by using an online questionnaire HowULearn (Parpala & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2012). HowULearn is an instrument designed to measure and support higher education students’ learning and studying and it contains different sections from various sources.

Personal identity

Personal identity was assessed with the short 11-item version (Marttinen et al., 2016) of the five-dimensional Dimensions for Identity Development Scale (DIDS; Luyckx et al., 2008). In the life domain of general future plans, respondents rate their commitment making (e.g. ‘I have decided on the direction I’m going to follow in my life’), identification with commitment (e.g. ‘My future plans give me self-confidence’), exploration in breadth (e.g. ‘I think actively about different directions I might take in my life’), exploration in depth (e.g. ‘I think about the future plans I already made’) and ruminative exploration (e.g. ‘I worry about what I want to do with my future’) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha scores of all variables used are reported in Table 1.

Motivations

The various motivations for attending university were measured with the 19-item Student Motivations for Attending University scale (SMAU; Côté & Levine, 1997, 2000). The scale consists of five subdimensions: personal-intellectual development (e.g. ‘University is satisfying because it gives me the opportunity to study and learn’), humanitarian (e.g. ‘I intend to use my education to contribute to the improvement of the human condition’), career-materialist (e.g. ‘University will help me to obtain the “finer things in life”’), expectation-driven (e.g. ‘There were considerable pressures on me from my family to get a university degree’) and default (e.g. ‘I am in university basically because there are few other options’), which are all rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Study burnout

Study burnout was measured with the 9-item Study Burnout Inventory (SBI-9; Salmela-Aro et al., 2009), used as a sum variable. Respondents rate items such as ‘I feel I am drowning in studying’ on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). Neither gender nor parental socioeconomic status was sought.

Data analysis strategy

First, two confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted with Mplus version 7.31 to evaluate whether the five-factor structures of both the DIDS and SMAU fit the data. The SBI-9 was not subjected to a CFA because it had been used several times before in HowULearn and was well established, whereas the DIDS and the SMAU were used for the first time. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; cutoff value for good fit close to 0.06), the comparative fit index (CFI; cutoff value close to 0.95) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; cutoff value close to 0.08) were used as fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Chi-square goodness of fit was reported although not used as a fit index due to being considered too conservative (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

Second, typical combinations of the identity dimensions were examined with latent profile analysis (LPA; Bergman et al., 2003). A series of models with progressively increasing numbers of profiles were evaluated with statistical criteria: a conventional index used to evaluate the fit of the model to the data is the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), where low scores indicate better fit than high scores. In LPA, the sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SA-BIC) is used to identify the best profile solution. The best solution is the one with the lowest BIC score. Occasionally, however, the BIC drops infinitely with increasing numbers of profiles, which makes evaluation of the best model impossible. Consequently, other indices such as the p-value of the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (pVLMR; a score below 0.05 suggests that the model fits the data better than a model with one less profile) and entropy (scores above 0.80 are preferred) may be considered (Bergman et al., 2003). The ‘elbow criterion’ allows an additional means to evaluate the optimal number of profiles (Masyn, 2013). The BIC score trajectories are examined for ‘elbow plots’, points where the drop in the BIC score is levelled, meaning the gains of increasing the number of profiles is diminished. More importantly, however, the selected solution should be parsimonious and theoretically sound. That is, a ‘lighter’ model with fewer profiles is preferable over a heavy one with a great number of profiles and the observed configurations on the different dimensions must make sense in the light of existing theory (Bergman et al., 2003).

Finally, the effects of identity profiles and field of study on burnout were examined with a two-way ANOVA, whereas the effects of identity profiles and field of study on motivations for attending university were examined with a two-way MANOVA.

Results

No outliers were removed. The CFA of the DIDS showed that the data fitted the five-dimensional model very well (BIC = 11781.800, χ2 (34, N = 430) = 90.766, p ≤ 0.000, RMSEA = 0.062, CFI = 0.968, SRMR = 0.042). By contrast, the data fitted the five-factor structure of the SMAU only after modifications (BIC = 15034.695, χ2 (67, N = 430) = 172.221, p ≤ 0.000, RMSEA = 0.060, CFI = 0.934, SRMR = 0.055). See the supplementary material for details. Means, correlations and reliability scores are reported in Table 1.

The LPA results are shown in Table 2. H1, that is, identifying five or six profiles found in earlier research, was not supported. Although the six-profile solution showed the lowest SA-BIC score among the range of models tested, the pVLMR scores indicated that models with more than three groups did not increase the model fit significantly. In addition, examining the SA-BIC score trajectory using the elbow criterion, there was an angle at the three-profile point. Thus, the three-profile solution was selected for further analyses (see Fig. 1). However, the three profiles identified were similar to those found in the past (e.g. Luyckx et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2011): individuals in diffusion (N = 84, 19.5%) scored low to very low on both commitment dimensions and exploration in depth, moderate on exploration in breadth and very high on rumination. Next, individuals in moderate moratorium (N = 197, 45.8%) scored moderate on both commitment dimensions and somewhat above the mean on exploration in breadth and even more so on ruminative exploration. Lastly, achievement consisted of individuals who showed an opposite pattern to their peers in diffusion.

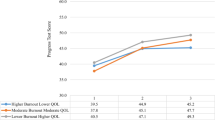

Regarding identity profiles and burnout, our second hypothesis was supported. That is, despite the fact that students in general scored very low on burnout, a two-way ANOVA showed that identity had a strong main effect on burnout (F(2, 424) = 27.29, p ≤ 0.000; ηp2 = 0.11), whereas field of study did not (F(1, 424) = 1.14, ns; ηp2 = 0.00). Nor was there any interaction effect between identity and field of study (F(2, 424) = 0.06, ns; ηp2 = 0.00). Diffusion (low commitment) scored highest on burnout, followed by moderate moratorium and achievement (high commitment).

Our third hypothesis examining the links between identity profiles and field of study was also supported (see Table 3). That is, while treating field of study as a continuous variable in an ANOVA, the results showed that the high commitment profile (i.e. achievement) was significantly more common among law students than among their peers in the humanities. Conversely, lower commitment and greater uncertainty (i.e. diffusion, moderate moratorium) were more common among students in the humanities than among those in law. Figure 2 shows the distribution of identity profiles according to the field of study.

Finally, exploring the impact of identity and field of study on motivations for attending university, our fourth hypothesis was also supported. First, a two-way MANOVA showed that identity had a main effect on motivations (F(10, 840) = 5.29, p ≤ 0.000; Wilks’ Λ = 0.89; ηp2 = 0.06). Despite the fact that students here generally scored very high on personal-intellectual development, humanitarian and career-materialist motives and very low on expectation-driven and default motives, the profiles showed significant differences on most of these dimensions. Achievement scored highest on the personal-intellectual development and career-materialist motives and lowest on the expectation-driven and default motives. Diffusion showed the opposite pattern. There were no differences between the profiles regarding the humanitarian motive. Second, field of study also had a main effect on motivations (F(5, 420) = 9.96, p ≤ 0.000; Wilks’ Λ = 0.89; ηp2 = 0.11), but its impact was almost exclusively on the career-materialist dimension (i.e. law students scored high, students in the humanities scored low). Third, there was no statistically significant interaction effect between identity and field of study regarding motivations (F(10, 840) = 0.81, ns; Wilk’s Λ = 0.98; ηp2 = 0.01).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the links between identity profiles, motives for attending university and burnout and in relation to field of study. First, the expected five or six identity profiles were not found. This might be due to LPA, which differs from the previously more common cluster analysis. The former builds on probabilities and fit indices and is sensitive to sample size (our sample was small), whereas the latter is considered more dependent on theory and researcher choice. However, in a previous study where Marttinen et al., (2016) employed LPA in a Finnish sample, roughly the size and mean age of ours, five identity profiles were identified. Thus, why only three profiles (i.e. diffusion, moderate moratorium, achievement) rather than five (or six) were found is left to speculation. Nonetheless, the profile patterns matched those found in previous studies (e.g. Luyckx et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2011; Zimmerman et al., 2013). Moderate moratorium was labelled such because its commitment and exploration levels were more moderate than in moratorium profiles previously found, meaning their scores were closer to the mean.

These results support recent theory and studies on increasing future-related uncertainty and anxiety among youth (Côté, 2019; Mannerström et al., 2017). Although an uncertain academic identity could to some degree be expected among first-year students due to, for example, new cognitive and social challenges (e.g. study technique, peer group; for academic identity, see Jensen & Jetten, 2016), this widespread lack of long-term commitments and direction is surprising. That is, most students (66%) were categorized within the low commitment-high exploration profiles (i.e. moderate moratorium and diffusion) (cf. Sica et al., 2014) although they had just recently made a choice regarding their educational path, fought against strong competition for a study place and then begun to study at university. In other words, they perceived their future as being rather diffuse despite their current commitments. Unfortunately, academic problems are very likely if students are unable to invest in and commit themselves to academic goals (Hejazi et al., 2012).

As expected, burnout was found to be much more prevalent among students profiled as diffusion and moderate moratorium than among their peers profiled as achievement. Although the sample mean of burnout was low and as such expected of first-year students (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017), the significant differences in burnout related to students’ sense of identity supports accounts on the importance of firm commitments for studying (Côté, 2018). If this certainty is lost, everyday tasks such as studying lose their meaning and they are experienced as demanding, and when forced to perform them, students experience exhaustion, cynicism and even inadequacy (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). Although directionality was not assessed in this study, theory and research point to reciprocal relationships between identity formation, academic motivation and burnout (Côté, 2019; Erentaitė et al., 2018).

Furthermore, a weak identity (diffusion and moderate moratorium profiles) was found to be significantly more common among students in the non-professional fields than among students in the professional field of study. Similar findings have been reported by Mikkonen et al. (2013) suggesting that exploration of one’s career identity is more common among students in generalist study programmes because the future career options are often unclear to the students. These students also suffered from more burnout, which suggests that occupational prospects might influence one’s sense of identity and protect against burnout. And yet, field of study did not have an independent impact on burnout beyond identity (see results on hypothesis 2). That is, a firm identity (e.g. ‘I am certain I want this’) weighs more in terms of (less) burnout than clear occupational prospects. Interestingly, this would imply that individuals applying for law studies are a more decisive, agentic and self-efficacious character type than their peers applying for the humanities. This would be in line with previous studies underlining the relative stability of identity (e.g. Meeus, 2018) and the impact of both intra-individual and environmental factors on identity development (Côté, 2016; Luyckx et al., 2014). Relatedly, Humburg, (2017) showed that in terms of personality differences, students in law are already emotionally more stable than their peers in the humanities, 6 years before applying to university.

Finally, an interesting contradiction emerged between motives for attending university and identity. As expected, in general, these first-year students scored very high on personal-intellectual development and low on expectation-driven and default motives (see Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012), and this pattern was positively related with an achieved identity. And yet, most of these same students lacked clear identities, which was associated with burnout. It is also known from earlier studies that most students will show slow study progression which, in turn, is linked with expectation-driven and default motives and a lack of motivation and interest in studies as well as with problems in adapting to one’s study programme (Baik et al., 2017; Korhonen & Rautopuro, 2012).

What this suggests, then, is that strong social desirability effects might be involved and that students are more expectation- and default-driven than they are ready to admit in surveys. Here, the DIDS reveals latent identity uncertainties that better predict forthcoming study progression than motivation measures. That is, students report personal-intellectual development because that is what is expected of them as agentic, self-sufficient individuals, yet they struggle with a dilemmatic—seemingly autonomous—decision regarding their educational/career track, as Côté, (2019). Obviously, this needs further research in the future, for instance, in the form of interviews probing societal expectations.

Broader implications

On the societal level, the present study highlights the importance of shifting the focus from low motivation and psychological problems as isolated, individual phenomena to identity issues. Identity is a normative developmental challenge and an increasingly difficult task to manage today due to structural transformations (Côté, 2018). That is, structural problems cannot be solved solely in counselling rooms. Having said that, it is still important to promote first-year students’ awareness of their future options within their academic track because uncertainty in goals and future plans has a negative influence on a student’s identity as a learner (Brunton & Buckley, 2021). On the institutional level, for example, faculty learning communities could organize events where students who have progressed further alumni, academics and professionals can meet. Academics in particular play an important role in helping students develop a sense of identity (Jensen & Jetten, 2016). Students’ identity could further be supported by having them write an identity portfolio in which the student reflects on how to become a professional and the importance of learned knowledge from a professional perspective. Students should also be offered courses in increasing psychological flexibility (e.g. ‘life design’; Burnett & Evans, 2016).

The results are nonetheless bound by some limitations and any generalizations should be cautious. First, the sample was not randomly chosen. Gender or socioeconomic background could not be controlled. Second, the cross-sectional sample meant that no inferences of development and causality could be inferred. Thus, future studies should assess changes in identity and burnout over several years in combination with students’ academic progress and achievement. Finally, the survey format did not allow us to scrutinize the meanings behind individual answers or what role social desirability might have played. Future studies would acquire a deeper and more solid understanding of factors involved in student mental health by combining quantitative and qualitative methods.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, our study adds to the discussion of the so-called student mental health crisis. First, the study showed that identity uncertainty was common among new university students. Second, this lack of identity was tied to burnout. Third, sense of identity explained burnout better than field of study. In other words, being certain in your choices is more important for psychological well-being than occupational prospects. Finally, measures of identity such as the DIDS might be better predictors of forthcoming study progression and well-being than measures of study motives.

Data availability

The raw data, analysis code and materials used in this study are neither openly available nor available upon request to the corresponding author. This is due to the nature of this research, where participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly. No aspects of the study were pre-registered.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2019). Conceptual foundations of emerging adulthood. In J. L. Murray & J. J. Arnett (Eds.), Emerging Adulthood and Higher Education: A New Student Development Paradigm (pp. 11–24). Routledge.

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., ... & Murray, E. (2018). WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638.

Bask, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Burned out to drop out: Exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(2), 511–528.

Bergman, L. R., Magnusson, D., & El-Khouri, B. M. (2003). Studying individual development in an interindividual context: A person-oriented approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Brunton, J., & Buckley, F. (2021). ‘You’re thrown in the deep end’: Adult learner identity formation in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2696–2709. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1767049.

Bühler, J. L., & Nikitin, J. (2020). Sociohistorical context and adult social development: New directions for 21st century research. American Psychologist, 75(4), 457–469.

Burnett, B., & Evans, D. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. Knopf Publishing Group.

Cannard, C., Lannegrand-Willems, L., Safont-Mottay, C., & Zimmermann, G. (2016). Brief report: Academic amotivation in light of the dark side of identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 179–184.

Carmo, R., Cantante, M. F., & de Almeida Alves, N. (2014). Time projections: Youth and precarious employment. Time & Society, 23(3), 337–357.

Côté, J. E. (2018). The enduring usefulness of Erikson’s concept of the identity crisis in the 21st century: An analysis of student mental health concerns. Identity, 18(4), 251–263.

Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. (1997). Student motivations, learning environments, and human capital acquisition: Toward an integrated paradigm of student development. Journal of College Student Development, 38(3), 229–242.

Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. (2000). Attitude versus aptitude: Is intelligence or motivation more important for positive higher-educational outcomes? Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 58–80.

Côté, J. E. (2016). The identity capital model: A handbook of theory, methods, and findings. Sociology Publications, 38. Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/sociologypub/38.

Côté, J. E. (2019). Youth development in identity societies: Paradoxes of purpose. Routledge.

Erentaitė, R., Vosylis, R., Gabrialavičiūtė, I., & Raižienė, S. (2018). How does school experience relate to adolescent identity formation over time? Cross-lagged associations between school engagement, school burnout and identity processing styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(4), 760–774.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and Society. Norton.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. 2 print ed. Norton.

Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2016). Identity formation in adulthood: A longitudinal study from age 27 to 50. Identity, 16, 8–23.

FSHS, Finnish Student Health Service (2016). Finnish student health survey. Retrieved January 8th, from https://www.yths.fi/en/fshs/research-and-publications/the-finnish-student-health-survey-2/.

Furlong, A., & Cartmel, F. (2009). Mass higher education. In A. Furlong (Ed.), Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood: New Perspectives and Agendas (pp. 121–126). Routledge.

Furlong, A., Goodwin, J., O’Connor, H., Hadfield, S., Hall, S., Lowden, K., & Plugor, R. (2016). Young People in the Labour Market: Past, Present. Routledge.

Guo, J., Eccles, J., Sortflex, F., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Gendered pathways towards STEM Careers: The incremential roles of work value profiles above academic task values. Frontiers in Psychology., 9, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01111

Heikkilä, A., Lonka, K., Nieminen, J., & Niemivirta, M. (2012). Relations between teacher students’ approaches to learning, cognitive and attributional strategies, well-being, and study success. Higher Education, 64(4), 455–471.

Hejazi, E., Lavasani, M. G., Amani, H., & Was, C. A. (2012). Academic identity status, goal orientation, and academic achievement among high school students. Journal of Research in Education, 22(1), 291–320.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Humburg, M. (2017). Personality and field of study choice in university. Education Economics, 25(4), 366–378.

Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(1), 3–10.

Jensen, D. H., & Jetten, J. (2016). The importance of developing students’ academic and professional identities in higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 57(8), 1027–1042. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0097

Kindelberger, C., Safont-Mottay, C., Lannegrand-Willems, L., & Galharret, J. M. (2020). Searching for autonomy before the transition to higher education: How do identity and self-determined academic motivation co-evolve? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 881-894.

Korhonen, V., & Rautopuro, J. (2012). Hitaasti mutta epävarmasti – onko opintoihin hakeutumisen lähtökohdilla yhteyttä opintojen käynnistymisongelmiin? [Slowly but hesitantly – Is there a connection between the reasons for studying and problems in getting started with studies]. In Opiskelijat korkeakoulutuksen näyttämöllä, 87–112.

Korhonen, V., Mattsson, M., Inkinen, M., & Toom, A. (2019). Understanding the multidimensional nature of student engagement during the first year of higher education. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1056.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31–53). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_2.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82.

Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Klimstra, T. A., & De Witte, H. (2010). Identity statuses in young adult employees: Prospective relations with work engagement and burnout. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 339–349.

Luyckx, K., Teppers, E., Klimstra, T. A., & Rassart, J. (2014). Identity processes and personality traits and types in adolescence: Directionality of effects and developmental trajectories. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2144–2153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037256

Lyndon, M. P., Henning, M. A., Alyami, H., Krishna, S., Zeng, I., Yu, T. C., & Hill, A. G. (2017). Burnout, quality of life, motivation, and academic achievement among medical students: A person-oriented approach. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6(2), 108–114.

Mannerström, R., Hautamäki, A., & Leikas, S. (2017). Identity status among young adults: Validation of the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS) in a Finnish sample. Nordic Psychology, 69(3), 195–213.

Mannerström, R., Muotka, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2019). Associations between success in developmental tasks and identity processes during the transition from emerging to young adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(9), 289–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.157117

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Marcia, J. E. (1993). The ego identity status approach to ego identity. In J. E. Marcia, A. S. Waterman, D. R. Matteson, S. L. Archer, & J. L. Orlofsky (Eds.), Ego identity: A handbook for psychosocial research (pp. 1–21). Springer.

Marttinen, E., Dietrich, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2016). Dark shadows of rumination: Finnish young adults’ identity profiles, personal goals and concerns. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 185–196.

Masyn, K. E. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods (pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. U. (Eds.). (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. Oxford University Press.

Meeus, W. (2018). The identity status continuum revisited: A comparison of longitudinal findings with Marcia’s model and dual cycle models. European Psychologist, 23(4), 289–299.

Meeus, W., Van De Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S. J., & Branje, S. (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescence. Child Development, 81(5), 1565–1581.

Mikkonen, J., Ruohoniemi, M., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2013). The role of individual interest and future goals during the first years of university studies. Studies in Higher Education, 38(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.564608

Mikkonen, J. (2012). Interest in university studies: its role and relation to other motivational variables [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki].

Parker, P., Thoemmes, F., Duineveld, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). I Wish I had (not) taken a Gap-Year? The Psychological and attainment outcomes of different post-school pathways. Developmental Psychology., 51(3), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038667

Parpala, A., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2012). Using a research instrument for developing quality at the university. Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), 313–328.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profile among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2014). School burnout and engagement in the context of demands-resources model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12018

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI) reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48–57.

Schwartz, S. J., Beyers, W., Luyckx, K., Soenens, B., Zamboanga, B. L., Forthun, L. F., . . . Waterman, A. S. (2011). Examining the light and dark sides of emergent adults’ identity: A study of identity status differences in positive and negative psychosocial functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 839–859.

Sica, L. S., Sestito, L. A., & Ragozini, G. (2014). Identity coping in the first years of university: Identity diffusion, adjustment and identity distress. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 159–172.

Zimmerman, G., Lannegrand-Willems, L., Safont-Mottay, C., & Cannard, C. (2013). Testing new identity models and processes in French-speaking adolescents and emerging adult students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 127–141.

Zivin, K., Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., & Golberstein, E. (2009). Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(3), 180–185.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital. This research was supported by the Academy of Finland research grants 320371, 336138 and 345132 to KSA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. AP, AH-M and TH performed the measurement. RM performed the statistical analyses, interpreted the results and drafted most parts of the manuscript, with others adding in more specific information. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rasmus Mannerström, PhD, was a postdoc researcher at the Department of Education, University of Helsinki, Finland, during work on the present study. Currently, he is a lecturer in Social Psychology at the Swedish School of Social Science at the University of Helsinki, Finland. His research interests include young adults’ identity troubles, study (a)motivation, values and political engagement in a sociohistorical perspective.

Anne Haarala-Muhonen, PhD, works as a senior lecturer in University Pedagogy at Centre for University Teaching and Learning (HYPE), University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on student learning and teaching at the university, for example, pedagogical practices, quality enhancement in the context of higher education, approaches to learning and student well-being. She also has strong expertise in teaching and studying during the first year of study.

Anna Parpala, PhD, is adjunct professor and University Lecturer at the University of Helsinki. She is university pedagogy expert and developer of the HowULearn measurement instrument used nationally and internationally. She contributes to several scientific journals and collaborates actively in international research projects. Her research focuses on learning, teaching and quality enhancement in higher education context.

Telle Hailikari, PhD, is an adjunct Professor and Senior lecturer at the University of Helsinki. She is an expert in university pedagogy and contributes to several scientific journals. Her research interests include learning and teaching at university and her research focuses on procrastination, well-being and students’ learning processes. She holds a doctoral degree in University pedagogy from the University of Helsinki.

Katariina Salmela-Aro, PhD, Academy professor, Professor of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Helsinki, Finland and Visiting Professor at the Institute of Education, University College London and Michigan State University, US. She is the President-Elect of the International Association of Applied Psychology and a member of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. She is director of several ongoing longitudinal studies among young people and a member of the EU granted EuroCohort study which aim is to develop a Europe wide longitudinal survey of child and youth well-being.

Most relevant publications

Asikainen, H., Salmela-Aro, K., Parpala, A., & Katajavuori, N. (2020). Learning profiles and their relation to study-related burnout and academic achievement among university students. Learning and Individual differences, 78, 101781.

Haarala-Muhonen, A., Ruohoniemi, M., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2011). Factors affecting the study pace of first-year law students: in search of study counselling tools. Studies in Higher Education, 36(8), 911–922.

Haarala-Muhonen, A., Ruohoniemi, M., Parpala, A., Komulainen, E., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). How do the different study profiles of first-year students predict their study success, study progress and the completion of degrees?. Higher Education, 74(6), 949–962.

Hailikari, T. K., & Parpala, A. (2014). What impedes or enhances my studying? The interrelation between approaches to learning, factors influencing study progress and earned credits. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(7), 812–824.

Hailikari, T., Tuononen, T., & Parpala, A. (2018). Students’ experiences of the factors affecting their study progress: Differences in study profiles. Journal of Further and higher Education, 42(1), 1–12.

Lindblom-Ylänne, S., Parpala, A., & Postareff, L. (2019). What constitutes the surface approach to learning in the light of new empirical evidence?. Studies in Higher Education, 44(12), 2183–2195.

Mannerström, R., Hietajärvi, L., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2021). A two-wave longitudinal study of identity profiles based on eight dimensions: Further insight into exploration and commitment quality as well as life domains central to identity. Identity, 21(2), 159–184.

Mannerström, R., Muotka, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2019). Associations between identity processes and success in developmental tasks during the transition from emerging to young adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(9), 1289–1307.

Parpala, A., Lindblom‐Ylänne, S., Komulainen, E., Litmanen, T., & Hirsto, L. (2010). Students’ approaches to learning and their experiences of the teaching–learning environment in different disciplines. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(2), 269–282.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28.

Salmela-Aro, K., Savolainen, H., & Holopainen, L. (2009). Depressive symptoms and school burnout during adolescence: Evidence from two cross-lagged longitudinal studies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(10), 1316–1327.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mannerström, R., Haarala-Muhonen, A., Parpala, A. et al. Identity profiles, motivations for attending university and study-related burnout: differences between Finnish students in professional and non-professional fields. Eur J Psychol Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00706-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00706-4