Abstract

This paper presents an exploratory case study which illustrates the first stage of our multi-stage methodology for translating gardens into a multisensory and accessible tour for blind and partially sighted (BPS) visitors and gathering feedback to be used in a future project on producing a smart audio descriptive guide to assist BPS visitors to appreciate gardens in a multisensory way. The key research questions are: how can the multisensory potential of gardens be translated into an accessible experience for BPS visitors? and to what extent can a smart audio descriptive guide enable access to gardens and provide multisensory visitor experiences primarily for BPS visitors? Our multi-stage methodology begins with an exploratory case study in which a group of BPS visitors were led by a human guide on a tour of the historic Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. The first stage involved the tour guide and accessibility expert working closely together to plan the multisensory garden tour. Then the actual tour of the gardens was carried out with a small group of BPS visitors. In-tour questions for the BPS visitors stimulated reflection and feedback, and interviews were carried out at the end of the tour. The paper presents some of the more significant observations which emerged from the tour, and draws conclusions about the extent to which a smart audio descriptive guide could provide many of the benefits of a human guide, and its advantages and inherent limitations. Some of these findings are relevant to those planning similar visits in other garden venues, including for broadening the application for universal access.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Green spaces are significant in people’s daily lives to connect to nature, to appreciate the variety of plants, to simply enjoy and relax, and to socialise with others. Green spaces especially played a crucial part in people’s quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic [32]. They provide substantial health and well-being advantages, as evidenced by the fact that green spaces across the UK provide the entire adult population with over \(\pounds \)34 billion health and wellbeing benefits per year [6]. Although practically any green area can facilitate a connection with the natural environment, gardens made and managed in accordance with evidence-based guidelines are acknowledged as being the most successful [26].

Gardens provide people with a space for recreation, education, and therapy outdoors [28]. Specifically, garden visits can yield pleasure [4], restore cognitive attention [14], reduce stress [27], and promote mental, physical and social well-being of people who live with disability [26]. As further explained by Abraham et al. [1],

landscapes have the potential to promote mental well-being through attention restoration, stress reduction, and the evocation of positive emotions; physical well-being through the promotion of physical activity in daily life as well as leisure time and through walkable environments; and social well-being through social integration, social engagement and participation, and through social support and security.

Garden visits generate great interest from the public; for example, there were about 1.9 million visitors to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and about 1.4 million visitors to the RHS Garden Wisley in 2021 [33]. These significant numbers show that gardens are popular attractions among visitors.

Gardens are potentially universally accessible through offering various sensory engagement experiences for visitors. Goulty [10] points out that gardens are “our most accessible art form”. Therefore, gardens have the potential to bring inclusive, enjoyable and memorable visitor experiences for people with various abilities regardless of age, sex, disability, ethnicity, origin, religion, economic or social status. One particular benefit for visitors is that gardens can stimulate their various senses, including sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste. Moreover, embracing the multisensory nature of a garden experience can be particularly interesting for BPS visitors.

Sensory and healing gardens have been shown to have a positive effect on a variety of visitors. Sensory gardens, which evolved from the traditional idea of “garden for the blind”, emphasise universal design and creation of multisensory landscapes to promote social inclusion and a range of sensory experiences [36]. Sensory gardens have been designed and created over the years across the world, such as in Poland [34], the UK [26], and Malaysia [12]. These sensory garden projects employ a proactive approach with the aim to make gardens universally accessible. They suggest good universal access practices and guidelines in creating sensory gardens. However, sometimes this is not always applicable for well-established and existing historic gardens when a reactive approach needs to be implemented.

As a both ancient and modern idea, healing gardens refer to “a variety of garden features that have in common a consistent tendency to foster restoration from stress and have other positive influences on patients, visitors and staff or care givers” [18]. These healing gardens offer people “a space to look out, and a space for passive or quasi-passive activities, such as observing, listening, strolling, sitting, exploring, and so on” [18].

There are various barriers which hinder people from benefitting from these opportunities. Some people, including BPS visitors, may find these venues are not fully accessible and inclusive in practice, for both sensory and physical reasons. A primary tool for addressing this is Audio Description (AD).

AD as a form of media accessibility, is usually verbal description of visual information, used to provide equal access services for BPS visitors. There is fruitful research on screen AD and museum AD, for example [7, 19, 20, 22, 29]. Other research also found out that AD could be beneficial to sighted museum visitors [13], in terms of achieving longer memorability after their visit. Moreover, a case study [5] on an inclusive audio descriptive online tour of the Chelsea Physic Garden was conducted to explore ways to bring garden experience to people at home during the Covid-19 Pandemic. However, less effort has been made to deliver AD in the context of gardens.

Gardens raise unique challenges for the venue to deliver AD for (but not limited to) BPS visitors. Firstly, gardens are constantly changing: they are growing, blossoming, decaying and renewing throughout the four seasons. Other dynamic factors include changing weather, active wildlife, changing colors and beauty, garden design, changes to the layout, etc. Secondly, gardens offer an inherently multisensory experience. This unique feature challenges the traditional concept of AD, which normally provides a verbal description of visual information. For gardens, we are proposing that the AD should convey multisensory information with the aim of stimulating all BPS visitors’ senses; in other words, AD should also guide visitors to explore the garden using their other senses so that BPS visitors could actively experience the gardens and find what a specific plant (such as an herb) looks like, smells like, how it feels, and even in some cases how it tastes. Thirdly, navigation challenges are heightened for BPS visitors. Natural terrain can present some access barriers and hazards for BPS visitors, e.g., water features (rivers and ponds), rocks, and slopes. This necessitates careful path planning beforehand. For these reasons, the development of an audio descriptive tour for gardens poses new challenges.

As a means of delivering AD in an outdoor context, there are several smartphone apps which have been developed to support visitors in gardens, such as the Kew Gardens app [17], the Jobim Botanic app [31], and the JBT app for the Tropical Botanical Garden of Lisbon [24]. However, these apps do not usually support BPS visitors. For enhancing the accessibility and visitor experience for BPS visitors in gardens, a few inclusive companion apps have been developed. The Gartenfreund app [2] offers BPS visitors an audio descriptive tour when they visit the botanical garden in Würzburg. The audio descriptive tour is activated by near-field communication (NFC), a short-range wireless communication technology. In this case, an AD of a significant plant nearby will be played when an NFC tag is scanned. The audio descriptive tour also features an interactive soundscape; for example, it plays the sounds of animals from the canopy level at which the phone is pointed. Likewise, the BFW Smartinfo app [8] uses NFC tags and QR codes for triggering audio information and Bluetooth beacons for navigation. The MindTags app [9] uses NFC tags, QR codes and Bluetooth beacons to provide self-reliance for BPS visitors [2].

However, there are some issues presented by these technologies. QR codes can be challenging for BPS visitors to precisely scan without being able to see where they are located. NFC tags require users to have prior knowledge of NFC technology and to be able to enable this sensor (if it exists) in the settings. Moreover, these companion apps focus primarily on enhancing the hearing experience rather than stimulating multiple senses for BPS visitors.

The context of the research presented in this paper is a longer-term research project to develop smart audio descriptive guides to provide an accessible multisensory experience in cultural and green space venues. We have developed a customisable voice-driven interactive smart audio descriptive guide primarily for BPS visitors in Titanic Belfast [35]. In this paper, however, the emphasis is on the first step of this longer-term multi-stage research project, which is to explore the potential to translate gardens into a multisensory tour for BPS visitors in a popular historic garden in Northern Ireland—the Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. This paper focuses on the period prior to having any AD. We use the human tour guide as a preliminary step towards defining the first version of the AD. The exploratory case study and its analysis presented in the paper lays the foundation for our future work to produce a smart audio descriptive guide in the context of gardens.

An overview photo of the Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. Nestled in the landscaped grounds of Hillsborough Castle and Gardens, this image shows a small white Lady Alice’s Temple sitting on a small hill. Framed by Yew Tree Walk, Lime Tree Walk and Moss Walk, it offers three very different views of the gardens. If visitors take a seat and pause for a moment, they could listen to the sounds of Lady Alice’s pond just in front of them [21]

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 first outlines our multi-stage methodology for producing an interactive smart audio descriptive guide for a tour of a specific venue by BPS visitors. Then it focuses on the design and execution of the actual tour of the Hillsborough Castle and Gardens by a group of BPS visitors. Section 3 analyses the feedback and observations from the visitors, expert human guide and accessibility expert. Section 4 then considers the potential advantages and limitations of using the smart audio descriptive guide for BPS visitors in gardens. Section 5 draws overall conclusions. The findings should be relevant to people who design similar garden tours.

2 Multi-stage methodology for producing an interactive smart audio descriptive guide

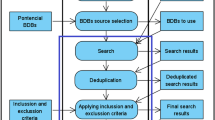

In this section, we follow our multi-stage methodology for eventually producing an interactive smart audio descriptive guide (sometimes shortened to ‘smart guide’). This methodology has two main stages—Stage A (Translating Gardens into a Multisensory Tour) and Stage B (Producing the Interactive Smart Audio Descriptive Guide). Both Stage A and Stage B contain some sub-stages, which are presented and followed in Subsection 2.1 and Subsection 2.2.

The first stage of our methodology begins with an experimental case study in which a group of BPS visitors were led by a human guide on a tour of the Hillsborough Castle and Gardens in Northern Ireland. This garden is well maintained, and intended to provide a range of sensory experiences. It offers unique historical stories and natural beauty for visitors. Hillsborough Castle was the residence for the royal family when they visited Northern Ireland and is now the official residence of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. The Hillsborough Castle’s gardens were developed from the 1760s onwards, and offer both an interesting historical context and a multisensory garden experience. Features of the garden include the Granville Garden, Lost Garden, Walled Garden, Willow House, Hydro House, the Ice House, the Garden’s Summer House, Yew Tree Walk, Moss Walk, Pinetum, Friends Burial Ground, the Lake and Lady Alice’s Temple [11]. An overview photo of the centre of the Hillsborough gardens is displayed in Fig. 1.

The space is inherently multisensory: visitors can look at colorful plants and flowers; listen to the fountain, the waterfalls and to the different bird songs; feel the different textures of leaves; smell the herbs and flowers, taste some herbs and (at times) fruits. The gardens also offer some specially designed installations for a range of sensory experiences, such as the bug hotel (for insects), a bare feet walking path where visitors can experience walking on different textures (such as mud and cobblestone), and a glasshouse. Menagerie Trails feature a robin trail and a kingfisher trail, which offer visitors a chance of encountering wildlife in the garden (such as swans, robins, and bees).

2.1 Stage A: Translating gardens into a multisensory tour

The first stage of the methodology (Stage A) is to plan and lead a safe and accessible garden tour where BPS visitors can actively participate in and explore multiple sensory experiences. This stage involves three main steps: (1) pre-planning the tour with an expert human guide, (2) performing the actual visit with BPS participants, and (3) feedback gathering and reflection.

2.1.1 Step 1: Pre-planning the tour with an expert human guide

The first step involved the tour guide and sighted accessibility expert working closely together to plan the path of the tour. The goal was to plan a multisensory experience, including hearing, touching, smelling and tasting. The guide also had to plan a safe route, such as avoiding dangerous slopes and stairways. The guide was a volunteer gardener and tour guide for the gardens, so he was familiar with all the potential tour stops. After a meeting among the tour guide, an accessibility expert and the researcher to plan the tour, detailed information about the garden tour was sent to the BPS participants, including the structure of the tour, in-tour and interview questions and the location of the venue.

2.1.2 Step 2: Performing the actual visit with BPS participants

After carefully planning the tour with the tour guide, we invited a small group of BPS and sighted participants to join the garden tour. There were seven people in the tour, one partially sighted (with physical disability), one registered blind, one sighted companion, one accessibility expert, one camera man who was recording the whole tour, the tour guide and the researcher herself. There were five males and two females with ages ranging from 18+ to 70. The whole tour lasts about four hours including greetings, the actual tour, an after-tour interview and a lunch at the Café of the Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. For the actual tour, 16 stops were planned. Different stops of the tour focused on a particular sensory experience, namely listening, touching, smelling, and tasting.

Based on these four senses, the paper presents some moments from the tour with BPS visitors. It shows how they use their senses to experience the plants and the spaces, by touching, smelling, listening and tasting.

(I) Listening experience

As one part of the planned listening experiences, we visited the fountain, the stream and listened to different bird songs. Figure 2 shows the fountain at the centre of the garden.

The fountain at the centre of the garden: This image shows a fountain in a pond surrounded by foliage. The water from the fountain cascades down into the pond creating ripples on its surface. The sky above is filled with white fluffy clouds that provide contrast to the deep green hues of the landscape below. Further away in the background are more trees, shrubs and a small white temple that add depth to this peaceful setting

(II) Touching experience

Touch tours are widely used nowadays in theatres and museums to engage BPS visitors multisensory experience, for example [3, 15, 16, 30]. For our garden tour, there were various touching experiences arranged for the BPS visitors, including touching sunflowers, plants with soft-textured leaves (Stachys byzantina/Lambs Ear), vegetables, wide trees, etc. BPS visitors were invited to feel the size and texture of these plants. Figure 3 shows a BPS participant touching a courgette in the garden. In this case, our tour guide emphasizes the ancient origins of the plants and their use in contemporary cooking.

In one part of the garden there was an unusual plant which had very large leaves (up to two meters across). See Fig. 4. The plant is Brazilian giant rhubarb (Gunnera manicata). Although they are very unusual, these leaves are actually dangerous to touch. The reverse side of the leaves have sharp needles. During the tour, therefore, the BPS participants were given options to touch or not touch the safe side of the plant.

The plant with large leaves (Brizalian giant rhubarb): this image shows the large, clump-forming herbaceous perennial Brizalian giant rhubarb which can reach heights of 2.5 ms and widths of 4 ms or more. The largest ever recorded has leaves as wide as 3.3 ms. Spikes cover the entire stalk and the underside of the leaf

(III) Smelling experience

The smelling experience was offered across a few regions in the garden, including the rose garden and the herb garden. Figure 5 shows a BPS participant smelling a wildflower in the garden.

(IV) Tasting experience

Because our visit was in mid-August, a number of the fruit trees had produced fruit. There were pears and apples which had just fallen to the ground. The participants were able to feel the fruit and then taste it. They also picked some blackberries, and tasted some of the herbs in the herb garden. Figure 6 shows a pear tree in the garden.

A pear tree in the garden: This image shows a pear tree in an outdoor setting. The plant has a thick trunk, with branches extending outwards from the top of the trunk. There are several leaves on each branch, and one large pear growing near the center of the frame. The pear is greenish-yellow in color, with some brown spots scattered across its surface. It appears to be ripe and ready for picking

2.1.3 Step 3: Feedback gathering and reflection

We gathered feedback in several ways. During the tour, the guide asked in-tour questions to BPS participants to stimulate their reflection, such as ‘how do you feel?’ or ‘Does that remind you of anything?’ The BPS participants’ own questions and feedback were noted and recorded, and a reflection session was carried out at the end of the tour. 14 questions were put to the BPS participants to reflect on their visitor experience and accessibility issues in the garden. We also interviewed the tour guide to ask him to reflect on his role, and the challenges he encountered during the tour. For a list of questions asked to the tour guide and BPS participants, see Appendix. Ethical approval for the research project was obtained through Queen’s University Belfast. Participants signed consent forms beforehand.

The whole tour was recorded on video (using GoPro),Footnote 1 as the information presented by the tour guide during the tour will serve as the basis for our AD scripts design. Before considering the second stage of our methodology (producing the actual interactive smart audio descriptive guide), there were several important and valuable observations made during the tour. These are considered in Sect. 3.

2.2 Stage B: Producing the actual interactive smart audio descriptive guide

Stage B contains two main stages. Firstly, we describe the tour in a diagrammatic digital representation suitable for the interactive smart audio descriptive guide. Secondly, we add to this diagrammatic representation the AD, navigation instructions and the Question and Answer database to produce the final interactive smart audio descriptive guide (see Sect. 4). This is then subjected to further trials and fine tuning. Section 4 deals with this Stage B. As we will discuss in Sect. 3, the case study raises some fundamental issues which need further research before producing the final smart audio descriptive guide.

3 Observations and reflections from BPS participants, the tour guide and the accessibility expert

As we gathered feedback from our BPS participants and the tour guide at Stage A (Step 3), in this section, we reflect the feedback and our observations, and present the findings under six main themes.

3.1 Understanding the size of objects

On several occasions, our tour guide wanted to communicate to the BPS visitors the size of particular objects in the garden, such as the height of a sunflower plant and the width of the actual sunflower (see Fig. 7), or the circumference of a famous tree in the garden (see Fig. 8). The response of one of the BPS participants to the sunflower was revealing. He remarked that the sunflower plant was “taller than I am”, and was surprised that the flower was “as big as my head”. This illustrates the basic principle that BPS people may prefer to understand the size of unfamiliar objects by comparing with other objects with which they are already familiar—such as themselves. When the participant reflected on the touch experience after the tour, the participant commented again on the size, “It was very memorable. I perhaps would remember it for a while. It is bigger than my head, you know”. The value of a tactile experience is that the visitor is able to make their own comparisons. This is important in scripting the AD for the smart audio descriptive guide (see Sect. 4). Here is an example extract from the live tour when one of our BPS participants was touching sunflowers:

-

Tour guide (TG): If you put your hand up, up, up\(\ldots \)you still cannot reach that sunflower.

-

TG: I will bring it down, it is so high.

-

BPS Participant (BP): Oh incredible! It is taller than I am.

-

TG: That’s the sunflower, and that is over two meters high.

-

TG: Put your hands up there. Feel that. One hand on each side, just feel that. And describe what you touch if you like.

-

BP: Is that one flower? It is as big as my head.

-

TG: That is one flower.

-

BP: It is like solid.

-

TG: It is huge, isn’t it? And what you are touching now is where it produces the sap. It is normally full of bees, but I can assure you there are no insects here to touch.

-

BP: Thank you.

-

BP: So this is sap here? (he touches the sap, smells it, and tastes it)

-

TG: Yes, that’s sap. It is yellow.

-

TG: Have you heard the saying, the “bee’s knees”?

-

BP: yeah.

-

TG: Ok, that comes from the fact that if you look at the bee, whenever it goes to a flower, it stores the nectar behind its knees.

-

BP: oh really?

-

TG: so you will see a little droplit of nectar behind its knees. So hence “bees knees”.

-

TG: Beneath it is a sunflower leaf. Feel the size of it. It is sticky.

-

BP: Oh, it is sticky.

This extract shows that there remains a lot of work before producing the actual AD for our smart guide. It shows that the dialogue between the guide and the visitor is much more interactive than could be achieved with a smart guide. This in turn highlights the challenge of converting the dialogue of a human guided tour into a smart guided tour.

3.2 The power of smell to evoke memories

Whilst touch is sometimes described in AD, smell is often entirely neglected within a descriptive experience. However, the significance of smell is “in its power to evoke, its connections to memory, place and emotions” [23]. Because smell has direct connections to areas of the limbic system that are involved in producing emotion and memories, smell has a specific ability to activate memories, especially emotionally charged ones [25]. At one point of the tour where the participants were encouraged to smell some flowers, one BPS participant said the scent reminded her of a time when she used to gather the same flowers with her mother. This illustrates that the sense of smell is particularly potent in evoking memories from one’s past. After our participant recalled her memory, the tour guide followed up her remark sensitively in a way which led her to share meaningful memories from her past. In other words, retrieving a personal memory suggests a deeper connection, which is likely to be more impactful on the visitor.

To describe the smell in gardens is not an easy task for an audio describer, as there are virtually no words for smells in European languages. Often we “borrow from taste terms (it smells sour) or describe the source of the smell (the smell of bacon, coffee, toast, seaweed, strawberries and so on)” [23]. Therefore, in a scent garden, as an alternative to a verbal description, the AD should invite BPS visitors to smell it.

3.3 Listening enhances the perception of nature

One part of the garden was a gathering point for birds. The guide asked the participants to listen to the bird songs. The guide identified the type of bird which make a particular song. This caused one participant to make the comment “I didn’t know different birds had their own song”. While some people can distinguish bird songs very expertly, this skill is not universal. The outcome was that the participant became much more observant of the sounds in the garden, and appreciated the variety and uniqueness of birds. More generally, the tour enhanced the ability of BPS participants to distinguish the different sounds in nature, and made the participants more observant of, and appreciative of, the diversity of the natural environment. Moreover, one of the BPS participants commented on the bird songs after their visit, “The robins, it helps me thinking of gardens. It sets the tone and it sort of gets the atmosphere going, reminded me of other natural places I have been to, like forests”.

3.4 Safety concerns

The paths through the garden presented several potential safety hazards. Sometimes the path narrowed through rocky formations which were difficult to navigate; it was found that up- and down-slopes could cause a fear of slipping; tree roots across the path were a tripping hazard; the path alongside the stream was slippery and overgrown; and some plants had stings, thorns or needles which had to be avoided. As a result, the tour had to be altered in some places, and some parts of the garden were omitted. See Fig. 9 for an example of a place which was omitted during the pre-planning stage for safety reasons.

Stone path in the garden: This image shows a large, grey stone bench situated in an outdoor rocky area. The bench is made of concrete and has two pillars on either side, with the rocks surrounding it providing a natural backdrop. There are several plants growing around the base of the bench, including some small shrubs and grasses. In addition to this, there is also a cave visible in the background

Another unexpected aspect was mentioned by a participant who explained that he could not bring his guide dog with him to the garden, because the dog (whose sense of smell is so acute) would be confused and unsettled by the sensory overload. This was another factor in raising the level of anxiety. Our tour guide quickly adapted to the need to give navigation information about what was coming next in the tour.

3.5 The value of a proactive guide

One popular point in the tour was an unusual plant (Brazilian giant rhubarb) whose leaves were about two meters wide. However, the reverse side of these leaves were covered with sharp needles which should not be touched. A less proactive guide would have bypassed these on the tour; but our guide gave the participants the option to touch the safe upper side of the leaves, and to feel their width and their texture. Therefore, with clear and careful guidance, the participants were able to explore the large size of the leaves without risk. Consequently, there was a recognised sense of accomplishment associated with engaging in activities that they were reluctant to try.

Being able to touch different plants was a memorable experience for the participants. Here is one quote from the BPS participants who commented on their touching experience, “Feeling so many different forms and so many different textures, something I never think. Flowers feels like flowers” and the participant continues “The different textures help me to remember which each of these is, especially without the visual memory obviously”.

3.6 The benefits of an empathetic guide

From time to time on the tour, the guide asked the participants what they were feeling after completing some parts of the garden tour. The ability to follow up the participants’ responses in a sensitive way sometimes led to a deeper discussion which proved meaningful. This was particularly the case when the participants had the opportunity to smell particular flowers or herbs. Our guide, while saying very little, proved empathetic and adept at leading the participants to talk about their memories and their life experiences.

Moreover, the guide also reflected on his interaction with the BPS participants during the tour; in his words: “This is a two-way travel of knowledge. The participants also have something to comment on and offer their knowledge and experience”. He also commented on his preparation for this garden tour; a quote from him: “To do this, whenever I came to this garden, I would sit there with my eyes closed, and just listen \(\ldots \) I hear the birds, the wind, and the waterfall \(\ldots \) I will do this again”.

4 Towards producing an interactive smart audio descriptive guide

In a previous research project, we developed a customisable voice-driven interactive smart audio descriptive guide [35]. This smart audio descriptive guide was developed in the context of enhancing accessibility and visitor experience of BPS visitors in museums. This smart audio descriptive guide uses speech recognition and high-quality speech synthesis for the AD and other interactions, such as visitors asking questions and receiving answers. A key feature of the smart guide is that it is customisable: the tour and associated AD and other features are described by a script file. This file can be edited without any change to the software. This means that the smart guide can be readily targeted to any museum. The tour, and the AD, can be updated by the museum staff without the requirement for significant in-house expertise or third-party experts. The use of high-quality speech synthesis removes the need to employ professional readers, which is particularly relevant when the tour or the AD needs to be updated at some time in the future. Having addressed the museum sector, this paper reports on our first exploration of the research question: to what extent could the smart audio descriptive guide be used to enhance accessibility and visitor experience of BPS visitors to gardens and green spaces?

When producing an audio descriptive guide for a museum, it is likely that the museum will already have a planned tour through the exhibits, and will have textual information for each exhibit and its significance. This is a good starting point for customising our smart guide in a museum context. But for tours of a garden, this is less likely to be the case. This is the reason why the first stage of our methodology was to have a human-led tour of the garden. The tour designed by the human guide, and the descriptions which the human guide used during the tour, then serve as the basis of the second stage of our methodology, which aims ultimately to result in a smart audio descriptive guide for tours of the garden.

4.1 Diagrammatic description of the tour and the AD

To represent the tour designed by the human guide digitally in a format that the smart guide can process, we describe the tour diagrammatically. Each stopping point in the tour is represented by a box in the diagram (see Fig. 10). Each box represents a location on the tour, such as the Glasshouse. Each box will have its own AD script (based on what the human guide said during the tour in Sect. 2). If there are sub-stages within this location, then the box will have its own set of boxes, in a hierarchical fashion.

The diagrammatic tour description allows parts of the tour to be defined as guide-led, and parts to be visitor-led. In a guide-led part of the tour, the visitors follow a predefined path through the sub-stages. This is indicated in the diagram by using solid interconnecting lines linking the sub-stages in sequence to their ‘parent’ box. For example, the tour of the Glasshouse in Fig. 10 has two sub-stages (‘Soft leaves’ and ‘Smell lavender’) which are visited in turn before exiting the Glasshouse.

A visitor-led part of the tour enables the visitor to select which (if any) of the sub-stages they wish to visit. This is indicated by dashed lines which connect the sub-stages to their ‘parent’ rather than to each other. For example, when the visitor arrives back at the Visitor Centre, they will be presented with three options: Gift Shop, Toilets and Restaurant. The visitor can select any or all (or none) of these options, in any order.

This form of diagram can also be used to give the visitor some control over how much AD they wish to listen to at a particular tour point. After playing the top level AD for the location, which will be given to everyone, the visitor can be given the option of more information. This enables the visitor to shape the amount of information they receive based on their own interests.

In addition to this tour description, it is possible to add in-tour questions which the smart guide will ask the visitor, such as “What did you think of the Glasshouse?” or other reflective questions. An in-tour question is incorporated into the diagram as a box with no sub-stages. At present, after the smart audio descriptive guide asks the question, the visitor’s response is not processed or recorded.

The smart audio descriptive guide also has a natural language ‘Question and Answer’ facility. It maintains a database of questions to which it has answers. For example, visitors could ask a question like “Who designed the Lady Alice’s Temple?”. Setting up this database can take some time. It can also be easily extended by adding new questions which it was unable to answer during a tour.

Our smart audio descriptive guide can also contain navigation instructions for getting from one point on the tour to the next. This is stored in another textual script file and can be edited to include warnings of potential dangers. At present, we do not utilise GPS-type location detection or other tracking technologies, so the smart guide would have to rely on the visitor following the navigation instructions correctly.

Finally, the smart audio descriptive guide can automatically gather (anonymised) statistics on the visitors’ use of the smart guide, such as which options they chose, or what questions they asked. This information can be used by the venue to update the AD on particular parts of the tour.

4.2 Reflections on the potential and limitations of a smart audio descriptive guide

In this section, we compare the experience of BPS visitors led by an expert human guide with an envisaged tour led by our smart audio descriptive guide. This will help to answer the question: to what extent can an interactive smart audio descriptive guide give a visitor experience approaching that of an expert human guide for garden tours for BPS visitors? We first highlight some benefits and advantages of the smart guide, and then consider the main limitations and issues which require further research.

4.2.1 Benefits and advantages of the smart audio descriptive guide

While an expert human guide is something of the gold standard for evaluating any garden tour, in practice there are limitations with this approach. The main issue is with guide availability. Normally guided tours have to be booked well in advance, and there is a limited number of suitable guides—particularly those who feel equipped to lead BPS visitors on a tour. Human guides who are expert in the venue still need additional training to lead a tour for BPS visitors.Footnote 2 Another issue is the cost of having a human guide. A smart audio descriptive guide does not suffer from these limitations. The smart guide can be delivered by an app on the visitor’s phone.

The normal alternative for BPS visitors to an expert-guided tour is to be accompanied by a friend or relative. In this case, the garden tour experience will be limited by the level of knowledge of the accompanying person, and their familiarity with all aspects of the venue. The smart audio descriptive guide, supplemented by the navigation capability of the accompanying person, will make the tour much more informative and multisensory for everyone.

For the same reasons, self-guided sighted visitors also typically miss out on many of the interesting aspects of a historic garden. Thus, a smart audio descriptive guide, with information supplied by an expert, can offer inclusive design to the benefits of a garden tour. The AD and navigation instructions can be supplemented by photographs of the features being described. This is beneficial to partially sighted visitors who can only see things close up and therefore may like to look closely at the images. This is also helpful to direct the attention of a sighted person.

Another benefit of our smart audio descriptive guide is that it offers the venue a comparatively low-cost route to providing an audio descriptive guide, since no software needs to be written and all the audio is synthesised automatically from the AD scripts using the Text-to-Speech technology, so no professional readers are involved. With some familiarisation of the tour description process through training videos, the diagrammatic tour description can be created using in-house resources. With this investment, cultural venues have a less resource-intensive way of meeting their legal obligations and aspirations in the area of accessibility.

Because gardens are dynamic environments, the details of a tour will normally vary depending on the season of the year. The venue can create a number of different guided tours, perhaps one for each season. One of the benefits is that visitors could even choose to listen to the summer descriptions in winter or autumn, as a way of transporting themselves to a different season. The smart audio descriptive guide can be set up to select the appropriate tour. If for some reason a part of the gardens is temporarily taken out of service, the diagrammatic representation of the tour can be edited to take account of any re-routing.

Moreover, the smart guide can offer a tour that provides both interpretation and actual description. This has a significant implication for our AD design. In other words, for the actual AD design in our next step, the AD will contain the historical context and factual information about the plants and gardens. In this case, the audio descriptive garden tour has the potential to be inclusive for diverse visitors, including sighted visitors. The design of the AD will be a collaborative team effort which will involve garden curators, BPS consultants, and audio describers.

4.2.2 Limitations of a smart audio descriptive guide

The primary limitation of a smart audio descriptive guide in the context of gardens was observed to be the issue of safety and navigation. As already noted, extensive gardens with water features and varied terrains present inherent hazards for BPS visitors. Straying from the path just a little can increase the risk and increase anxiety. There is potential danger in touching the wrong plants, or tasting the wrong plants, or tripping over branches or roots. Such features are too fine-grained for any GPS-like navigation system.

Therefore, our recommended approach is for BPS visitors to be accompanied by a friend or relative. The reason is that the audio descriptive guide as it currently stands does not provide a high-grained navigation system, and so some BPS visitors might prefer to visit with someone or to join a tour. In this regard, our approach to using a smart audio descriptive guide for visiting gardens is different from a museum tour, which is typically a more controlled environment and freer from hazards.

Another limitation of a smart audio descriptive guide, compared with a human guide, is how to encourage the visitor to talk about their memories and life experiences which the tour may evoke. People react differently to interacting with technology: some people feel free to speak naturally to a device, while others can feel embarrassed. The sharing of a memory or life experience is a valuable benefit of visiting gardens. It is difficult to see how an automated guide can rival an empathetic human guide in this regard in the foreseeable future. While we can include reflective questions in the AD, the smart audio descriptive guide cannot respond meaningfully to what the visitor says.

5 Conclusions

This research has presented a case study in designing, leading and reflecting on a tour for BPS visitors of an historic garden. The study has also provided the basis of evaluating the potential use of an interactive smart audio descriptive guide for garden tours for BPS visitors.

One of the main contributions of this work is to extend the concept of AD to embrace multisensory experiences rather than the traditional verbal description of visual information. Rather than thinking of this as a special case, our concept is that AD creation should from the outset aim to be multisensory. Moreover, one of the ways this research extends the concept of AD is to include the outdoor world. This introduces additional variables, such as weather and seasonal changes.

The description of our multisensory tour designed in collaboration with a knowledgeable human tour guide has shown how it is possible to incorporate opportunities into the tour for stimulating the senses of hearing, touching, smelling and tasting.

The review of the tour, the observations and the feedback has highlighted a number of points which should be of benefit to others who may be developing garden tours for BPS visitors, with or without technology assistance. It was clear that a proactive and responsive guide can do much to make the visitor experience of gardens more meaningful and memorable.

The paper also demonstrated that many aspects of the human guided tour can be emulated by an interactive smart audio descriptive guide for BPS visitors to gardens. The foundational step was to define a diagrammatic representation of the tour, and to supplement this with the AD based on the human guide’s descriptions and with navigation instructions. This approach offers many benefits to green space venues. It addresses the problem of expert human guide availability. It offers the venue a comparatively rapid and adaptable way of meeting legal obligations and aspirations for accessibility. It can lead visitors on a much more meaningful, accessible, and multisensory tour than a self-guided tour.

The paper also highlights some key limitations of an automated audio descriptive guide which are specific to gardens. Without integrating a fine-grained navigation system, the guide could not track the accurate location of the users so could not alert users to some potential trip hazards. The other limitation of a smart audio descriptive guide is that it cannot emulate a responsive human guide. This is more likely to be important in the context of a garden visit, because the multisensory experience is likely to evoke memories of life experiences which visitors would like to share.

To conclude, garden visits uniquely offer the chance to stimulate a wide range of our senses. Gardens have the potential to give an inclusive, enjoyable, emotionally engaging and memorable visitor experience for all visitors. Access to these experiences should be universal. Our study also revealed how a well-led multisensory tour can make visitors more observant of the natural environment. It is hoped that it also will make visitors more appreciative of our natural environment, and be motivated to preserve and protect it. In this way the study adds to society’s effort to create a sustainable environment for all. For future work, user testing of the smart guide prototype with both end users and venues will be conducted. This phase of evaluation is critical for identifying usability challenges and gathering insightful feedback, which will be instrumental in enhancing the guide’s functionality.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

The smart audio descriptive guide software is under ongoing development and is not currently available for distribution.

Notes

GoPro is a versatile action camera and all the video footage shot by GoPro is stored in the GoPro cloud with password protection.

Hillsborough Castle and Gardens currently are training their tour guides for leading audio descriptive tours for BPS visitors.

References

Abraham, A., Sommerhalder, K., Abel, T.: Landscape and well-being: a scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 55, 59–69 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0069-z

Birnstiel, S., Steinmüller, B., Bissinger, K., et al.: Gartenfreund: exploring the botanical garden with an inclusive app. In: Alt, F., Bulling, A., Döring, T. (Eds.) Proceedings of Mensch und Computer, pp. 499–502. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3340764.3344446

Christidou, D., Pierroux, P.: Art, touch and meaning making: an analysis of multisensory interpretation in the museum. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 34(1), 96–115 (2019)

Connell, J., Meyer, D.: Modelling the visitor experience in the gardens of Great Britain. J. Curr. Issues Tourism 7(3), 183–216 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667979

Eardley, A.F., Thompson, H., Fineman, A., et al.: Devisualizing the museum: from access to inclusion. J. Mus. Educ. 47(2), 150–165 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2022.2077067

Fields in Trust: Revaluing Parks and Garden Spaces. Tech. rep. https://www.fieldsintrust.org/Upload/file/research/Revaluing-Parks-and-Green-Spaces-Summary.pdf (2018)

Fryer, L.: An Introduction to Audio Description: A Practical Guide. Routledge, London (2016). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315707228

Google Play: BFW SmartInfo. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.bfwonline.smartinfo &hl=en_GB &gl=US (2023)

Google Play: MindTags. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=net.mindtagsbeta &hl=en &gl=US (2023)

Goulty, S.M.: Heritage Gardens: Care, Conservation, Management. Routledge, London (1993). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203168059

Historic Royal Palaces: Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. https://www.hrp.org.uk/hillsborough-castle/#gs.uqkdo9 (2023)

Hussein, H., Omar, Z., Ishak, S.A.: Sensory garden for an inclusive society. Asian J. Behav. Stud. 1(4), 33–43 (2016)

Hutchinson, R.S., Eardley, A.F.: Inclusive museum audio guides: ‘guided looking’ through audio description enhances memorability of artworks for sighted audiences. J. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 36(4), 427–446 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2021.1891563

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S.: The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1989)

Lacey, S., Sathian, K.: Please do touch the exhibits! interactions between visual imagery and haptic perception. In: The Multisensory Museum: Cross disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory and Space, pp. 3–16 (2014)

Levent, N., Pascual-Leone, A.: The Multisensory Museum: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. Rowman & Littlefield (2014)

Mann, C.: A study of the iPhone app at Kew Gardens: improving the visitor experience. In: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts (EVA 2012), London, pp. 8–14 (2012). https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2012.5

Marcus, C.C., Barnes, M.: Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations. Wiley, New York (1999)

Maszerowska, A., Matamala, A., Orero, P. (eds.): Audio Description: New Perspectives Illustrated. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam (2014)

Matamala, A., Orero, P. (Eds.): Researching Audio Description: New Approaches. Springer, London (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56917-2

McCann, D.: Hillsborough castle and gardens visitor facilities. RIBA J. 6, 66 (2020)

Neves, J.: Cultures of accessibility: Translation making cultural heritage in museums accessible to people of all abilities. In: Harding, S., Cortés, O.C. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Culture, pp. 415–430. Routledge, London (2018)

Pennycook, A., Otsuji, E.: Making scents of the landscape. J. Linguist. Landc. 1(3), 191–212 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.3.01pen

Postolache, S., Torres, R., Afonso, A.P., et al.: Contributions to the design of mobile applications for visitors of Botanical Gardens. J. Procedia Comput. Sci. 196, 389–399 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROCS.2021.12.028

Smith, B.C.: Proust, the madeleine and memory. J. Mem. Twenty-First Century (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137520586_3

Souter-Brown, G.: Landscape and Urban Design for Health and Well-Being: Using Healing, Sensory and Therapeutic Gardens. Routledge, London (2014)

Souter-Brown, G., Hinckson, E., Duncan, S.: Effects of a sensory garden on workplace wellbeing: a randomised control trial. J. Landsc. Urban Plan. 207, 103997 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103997

Spring, J.A.: Design of evidence-based gardens and garden therapy for neurodisability in Scandinavia: data from 14 sites. J. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 6(2), 87–98 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.16.2

Taylor, C., Perego, E.: The Routledge Handbook of Audio Description. Routledge, London (2022)

Udo, J.P., Fels, D.I.: Enhancing the entertainment experience of blind and low-vision theatregoers through touch tours. Disabil. Soc. 25(2), 231–240 (2010)

Velho, L., Groetaers, F.: Jobim botanic. In: SIGGRAPH Asia 2014 Mobile Graphics and Interactive Applications, pp. 1–6. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2014). https://doi.org/10.1145/2669062.2669065

Venter, Z., Barton, D., Gundersen, V., et al.: Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. J. Environ. Res. Lett. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abb396

Visit Britain: Visitor Attraction Trends in England 2021 Full Report (2021). https://www.visitbritain.org/sites/default/files/vb-corporate/2022-09-06_england_attractions_2021_trends_report.pdf

Wajchman-Świtalska, S., Zajadacz, A., Lubarska, A.: Recreation and therapy in urban forests—the potential use of sensory garden solutions. J. For. 12(10), 1402 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101402

Wang, X., Crookes, D., Harding, S., et al.: Evaluating audio description and emotional engagement for BPS visitors in a museum context. J. Transl. Spaces 11(1), 134–156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21019.wan

Zajadacz, A., Lubarska, A.: International Journal of Spa and Wellness Sensory gardens in the context of promoting well-being of people with visual impairments in the outdoor sites. J. Spa Wellness 2(1), 3–17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2019.1668674

Funding

This research project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action, Grant Agreement No. 754507.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XW wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all the figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This research was approved by the ethics committee of the School of Arts, English and Languages at Queen’s University Belfast, UK. All participants were informed of the study process, signed a consent form and volunteered to take part in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: List of questions

Appendix: List of questions

1.1 Pre-tour briefing

Thanks for joining us to the garden tour today. Our tour guide is Jim Walker, he will guide us to a multisensory tour today. If you have any questions, or if you want to know more about something, just ask the guide. At one or two points, the guide may hand control of the next part of the tour to you. You decide the path based on your interest!

1.2 Questions during the tour

-

Does this plant/feature make you think of anything, or remind you of anything?

-

How would you describe your feelings/emotions at the minute?

1.3 Questions to the BPS participants after the tour

-

What smells do you remember?

-

Was there one smell in particular which you remember? Did it make you think of anything, or remind you of anything?

-

What sounds do you recall hearing?

-

Was there one sound which was particularly memorable? What did it do for you?

-

Can you specially remember touching anything? What did this communicate to you?

-

What do you remember about the tasting? What words came to mind? (reaction)

-

Did you find any moments or aspects of the tour which made you feel uncomfortable—were you worried or afraid at any time, even slightly?

-

Were you bored or disinterested at any points in the tour? Which points?

-

How interesting did you find the historical background about the item (1–5, 5 = best)?

-

Is there anything which might have made the visit better or more memorable?

-

Would you have liked to have had more control over the places which the tour visited? Could you give an example?

-

How would you rate your overall visiting experience? (on a scale of 1 to 5, 5 = best)

-

If you were able to have an app as a smart audio descriptive guide for visiting this garden on your own (or with a friend), what would you recommend about the features it should have?

-

Are there any further comments you want to make?

1.4 Questions to the tour guide after the tour

-

What challenges did you face in creating and leading a guided tour for BPS visitors?

-

Where do you need advice from us? What is your input while preparing the tour?

-

If you were to do the tour again, what changes might you make?

-

Have you any other comments about the process?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X. Translating gardens into accessible multisensory tours for blind and partially sighted visitors: an exploratory case study. Univ Access Inf Soc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-024-01107-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-024-01107-0