Abstract

Background

Delayed diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) is common because the changes in renal function markers often lag injury. We aimed to find optimal non-invasive hemodynamic variables for the prediction of postoperative AKI and AKI renal replacement therapy (RRT).

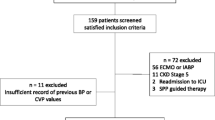

Methods

The data were collected from 1,180 patients who underwent cardiac surgery in our hospital between March 2015 and Feb 2016. Postoperative central venous pressure (CVP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate, PaO2, and PaCO2 on ICU admission and daily fluid input and output (calculated as 24 h PFO) were monitored and compared between AKI vs. non-AKI and RRT vs non-RRT cases.

Results

The AKI and AKI-RRT incidences were 36.7% (n = 433) and 1.2% (n = 14). Low cardiac output syndromes (LCOSs) occurred significantly more in AKI and RRT than in non-AKI or non-RRT groups (13.2% vs. 3.9%, P < 0.01; 42.9% vs. 7.1%, P < 0.01). CVP on ICU admission was significantly higher in AKI and RRT than in non-AKI and non-RRT groups (11.5 vs. 9.0 mmHg, P < 0.01; 13.3 vs. 9.9 mmHg, P < 0.01). 24 h PFO in AKI and RRT cases were significantly higher than in non-AKI or non-RRT patients (1.6% vs. 0.9%, P < 0.01; 3.9% vs. 0.8%, P < 0.01). The areas under the ROC curves to predict postoperative AKI by CVP on ICU admission (> 11 mmHg) + LCOS + 24 h PFO (> 5%) and to predict AKI-RRT by CVP on ICU admission (> 13 mmHg) + LCOS + 24 h PFO (> 5%) were 0.763 and 0.886, respectively.

Conclusion

The volume-associated hemodynamic variables, including CVP on ICU admission, LCOS, and 24 h PFO after surgery could predict postoperative AKI and AKI-RRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Xu J, Ding X, Fang Y, Shen B, Liu Z, Zou J, et al. New, goal-directed approach to renal replacement therapy improves acute kidney injury treatment after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8090-9-103.

Yang XM, Tu GW, Gao J, Wang CS, Zhu DM, Shen B, et al. A comparison of preemptive versus standard renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):205–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.073.

O'Neal JB, Shaw AD, Billings FTt. Acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery: current understanding and future directions. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1352-z.

Ding X, Cheng Z, Qian Q. Intravenous fluids and acute kidney injury. Blood Purif. 2017;43(1–3):163–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000452702.

Litton E, Morgan M. The PiCCO monitor: a review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40(3):393–409.

Palomba H, de Castro I, Neto AL, Lage S, Yu L. Acute kidney injury prediction following elective cardiac surgery: AKICS score. Kidney Int. 2007;72(5):624–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002419.

Gelman S. Venous function and central venous pressure: a physiologic story. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):735–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181672607.

Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, Barsoum RS, Burdmann EA, Goldstein SL, et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138.

Gillespie RS, Seidel K, Symons JM. Effect of fluid overload and dose of replacement fluid on survival in hemofiltration. Pediatr Nephrol (Berlin, Ger). 2004;19(12):1394–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-004-1655-1.

Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Barton J, Burns KE, Friedrich JO, House AA, et al. Clinical factors associated with initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury-a prospective multicenter observational study. J Crit Care. 2012;27(3):268–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.06.003.

Maganti MD, Rao V, Borger MA, Ivanov J, David TE. Predictors of low cardiac output syndrome after isolated aortic valve surgery. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I448–I45252. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.104.526087.

Doty JM, Saggi BH, Sugerman HJ, Blocher CR, Pin R, Fakhry I, et al. Effect of increased renal venous pressure on renal function. J Trauma. 1999;47(6):1000–3.

Firth JD, Raine AE, Ledingham JG. Raised venous pressure: a direct cause of renal sodium retention in oedema? Lancet (Lond, Engl). 1988;1(8593):1033–5.

Winton FR. The influence of venous pressure on the isolated mammalian kidney. J Physiol. 1931;72(1):49–61.

Chen KP, Cavender S, Lee J, Feng M, Mark RG, Celi LA, et al. Peripheral Edema, Central Venous Pressure, and Risk of AKI in Critical Illness. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2016;11(4):602–8. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.08080715.

Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, et al. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(7):589–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068.

Schrier RW. Role of diminished renal function in cardiovascular mortality: marker or pathogenetic factor? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.067.

Lopez-Delgado JC, Esteve F, Javierre C, Perez X, Torrado H, Carrio ML, et al. Short-term independent mortality risk factors in patients with cirrhosis undergoing cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16(3):332–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivs501.

Wang XT, Liu DW, Chai WZ, Long Y, Cui N, Shi Y, et al. The role of central venous pressure to evaluate volume responsiveness in septic shock patients. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2008;47(11):926–30.

Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada TA, Walley KR, Russell JA. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):259–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15.

Deruddre S, Cheisson G, Mazoit JX, Vicaut E, Benhamou D, Duranteau J. Renal arterial resistance in septic shock: effects of increasing mean arterial pressure with norepinephrine on the renal resistive index assessed with Doppler ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1557–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0665-4.

Algarni KD, Maganti M, Yau TM. Predictors of low cardiac output syndrome after isolated coronary artery bypass surgery: trends over 20 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1678–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.017.

McFarlane SI, Winer N, Sowers JR. Role of the natriuretic peptide system in cardiorenal protection. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2696–704. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.22.2696.

Damman K, Navis G, Smilde TD, Voors AA, van der Bij W, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Decreased cardiac output, venous congestion and the association with renal impairment in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(9):872–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.05.010.

Bouchard J, Soroko SB, Chertow GM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Paganini EP, et al. Fluid accumulation, survival and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2009;76(4):422–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.159.

Payen D, de Pont AC, Sakr Y, Spies C, Reinhart K, Vincent JL. A positive fluid balance is associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute renal failure. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R74. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc6916.

Xu J, Shen B, Fang Y, Liu Z, Zou J, Liu L, et al. Postoperative fluid overload is a useful predictor of the short-term outcome of renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(33):e1360. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001360.

Desai KV, Laine GA, Stewart RH, Cox CS Jr, Quick CM, Allen SJ, et al. Mechanics of the left ventricular myocardial interstitium: effects of acute and chronic myocardial edema. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(6):H2428–H24342434. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00860.2007.

Rosenberg AL, Dechert RE, Park PK, Bartlett RH. Review of a large clinical series: association of cumulative fluid balance on outcome in acute lung injury: a retrospective review of the ARDSnet tidal volume study cohort. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24(1):35–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066608329850.

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):55–63. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0697.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Kidney and Blood Purification (Grant number. 14DZ2260200); Shanghai Clinical Medical Center for Kidney Disease Project support by Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (Grant number. 2017ZZ01015); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number. 81901939); Shanghai “science and technology innovation plan” popular science project (Grant number 19DZ2321400) and Xiamen Science and Technology Plan in 2018 (Grant number. 3502Z20184009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Human participants and/or animals

The ethical committee of the Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital approved the study (No. B2017-039) and our study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Jiang, W., Li, Y. et al. Volume-associated hemodynamic variables for prediction of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury. Clin Exp Nephrol 24, 798–805 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-020-01908-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-020-01908-6