Abstract

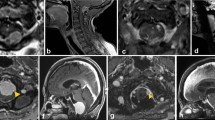

The objective of the study is to describe our experience in the surgical management of foramen magnum meningiomas with regard to the clinical–radiological findings, the surgical approach and the outcomes after mid-term follow up. Over a 5-year period, 15 patients presenting with meningiomas of the foramen magnum underwent surgical treatment. The medical records were reviewed in order to analyze the clinical–radiological aspects, as well as the surgical approach and the outcomes. Based on the preoperative magnetic resonance imaging exams, the tumors were classified as anterior or anterolateral in the axial slices and clivospinal or spinoclival in the sagittal slices. The lateral approach was used in all cases. However, the extent of bone removal and the management of the vertebral artery were tailored to each patient. Fourteen patients were females, and one was male, ranging in age from 42 to 74 years (mean 55,9 years). The occipital condyle was partially removed in eight patients, and in seven patients, removal was not necessary. Total removal of the tumor was achieved in 12 patients, subtotal in two, and partial resection in one patient. Postoperative complications occurred in two patients. Follow-up ranged from 6 to 56 months (mean 23.6 months).There was no surgical mortality in this series. The extent of the surgical approach to foramen magnum meningiomas must be based on the main point of dural attachment and tailored individually case-by-case. The differentiation between the clivospinal and spinoclival types, as well as anterior and anterolateral types, is crucial for the neurosurgical planning of foramen magnum meningiomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arnautovic KI, Al-Mefty O, Husain M (2000) Ventral foramen magnum meninigiomas. J Neurosurg 92:71–80

Babu RP, Sekhar LN, Wright DC (1994) Extreme lateral transcondylar approach: technical improvements and lessons learned. J Neurosurg 81:49–59

Baldwin HZ, Miller CG, van Loveren HR, Keller JT, Daspit CP, Spetzler RF (1994) The far lateral/combined supra- and infratentorial approach. A human cadaveric prosection model for routes of access to the petroclival region and ventral brain stem. J Neurosurg 81:60–68

Bassiouni H, Ntoukas V, Asgari S, Sandalcioglu EI, Stolke D, Seifert V (2006) Foramen magnum meningiomas: clinical outcome after microsurgical resection via a posterolateral suboccipital retrocondylar approach. Neurosurgery 59:1177–1185; discussion 1185–1177

Bertalanffy H, Seeger W (1991) The dorsolateral, suboccipital, transcondylar approach to the lower clivus and anterior portion of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery 29:815–821

Boulton MR, Cusimano MD (2003) Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus 14:e10

Bruneau M, George B (2008) Foramen magnum meningiomas: detailed surgical approaches and technical aspects at Lariboisiere Hospital and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 31:19–32; discussion 32–13

David CA, Spetzler RF (1997) Foramen magnum meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg 44:467–489

George B (1991) Meningiomas of the foramen magnum. In: Schmidek HH (ed) Meningiomas and Their Surgical Management. Saunders (W.B.) Co Ltd, Philadelphia, pp 459–470

George B, Lot G, Boissonnet H (1997) Meningioma of the foramen magnum: a series of 40 cases. Surg Neurol 47:371–379

Goel A, Desai K, Muzumdar D (2001) Surgery on anterior foramen magnum meningiomas using a conventional posterior suboccipital approach: a report on an experience with 17 cases. Neurosurgery 49:102–107

Kratimenos GP, Crockard HA (1993) The far lateral approach for ventrally placed foramen magnum and upper cervical spine tumours. Br J Neurosurg 7:129–140

Margalit NS, Lesser JB, Singer M, Sen C (2005) Lateral approach to anterolateral tumors at the foramen magnum: factors determining surgical procedure. Neurosurgery 56:324–336

Menezes AH, Traynelis VC, Fenoy AJ, Gantz BJ, Kralik SF, Donovan KA (2005) Honored guest presentation: surgery at the crossroads: craniocervical neoplasms. Clin Neurosurg 52:218–228

Meyer FB, Ebersold MJ, Reese DF (1984) Benign tumors of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg 61:136–142

Miller E, Crockard HA (1987) Transoral transclival removal of anteriorly placed meningiomas at the foramen magnum. Neurosurgery 20:966–968

Samii M, Klekamp J, Carvalho G (1996) Surgical results for meningiomas of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery 39:1086–1095

Sawaya RA (1998) Foramen magnum meningioma presenting as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosurg Rev 21:277–280

Sekhar LN, Wright DC, Richardson R, Monacci W (1996) Petroclival and foramen magnum meningiomas: surgical approaches and pitfalls. J Neurooncol 29:249–259

Sen CN, Sekhar LN (1990) An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery 27:197–204

Spektor S, Anderson GJ, McMenomey SO, Horgan MA, Kellogg JX, Delashaw JB Jr (2000) Quantitative description of the far-lateral transcondylar transtubercular approach to the foramen magnum and clivus. J Neurosurg 92:824–831

Suhardja A, Agur AM, Cusimano MD (2003) Anatomical basis of approaches to foramen magnum and lower clival meningiomas: comparison of retrosigmoid and transcondylar approaches. Neurosurg Focus 14:e9

Wen HT, Rhoton AL Jr, Katsuta T, de Oliveira E (1997) Microsurgical anatomy of the transcondylar, supracondylar, and paracondylar extensions of the far-lateral approach. J Neurosurg 87:555–585

Yasargil MG, Mortara RW, Curcic M (1980) Meningiomas of basal posterior cranial fossa. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg 7:111–115

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

Volker Seifert, Frankfurt, Germany

Borba et al., in their paper, present a relatively small series of 15 patients with foramen magnum meningiomas operated on over a period of 5 years. The clinical classification was based on the well-known and widely applied classification proposed by Bernhard George already in 1991 and extended in 1997 in his landmark publications on foramen magnum meningiomas. I have my problems in the application of the clivospinal and spinoclival terminology, which the authors have also used, which I think is very arbitrary and does not add to the classification or to the pre- or intraoperative decision making. The surgical approach of Borba et al. is straightforward with a small suboccipital craniotomy and a hemilaminectomy on the side of the meningioma. In selected cases, they have partially removed the condyle of the respective side. Approaches to the craniocervical region have been described by several authors starting as early as 1991 with the well-known publication of Bertalanffy in which the transcondylar variation has been described in detail for the first time. I agree with Borba and co-workers that foramen magnum meningiomas can be reached with a straightforward procedure using a lateral exposure. We and others have shown that by using the far lateral paracondylar approach, meningiomas of all sizes can be safely removed. The foramen magnum meningioma is probably the only skull base meningioma which can be the more easily removed the larger the tumor is. Almost all large foramen magnum meningiomas show a distinct lateralization, and have, by their mere size and transposition of the spinal cord, created a convenient and elegant to be used working corridor. However, I also agree that in selected cases, especially in small tumors, located exclusively anterior to the spinal cord, partial removal of the condyle, may be helpful in getting an atraumatic access to these lesions.

The surgical results of Borba are in agreement with those of other recent studies with total removal in 12, subtotal in two, and partial resection in one patient and postoperative complications occurring in only two patients.

In summary, the publication of Borba et al. confirms the basic and well-established principles of foramen magnum meningioma surgery which have been outlined by previous larger studies and therefore adds to the increasing evidence that these treacherous tumors can be safely and completely removed in the vast majority of patients, by applying modern skull base surgery techniques.

Michaël Bruneau, Brussels, Belgium, Bernard George, Paris, France

Borba et al. described a series of patients operated on foramen magnum meningiomas and have to be commended for their good results in the management of such difficult cases. They classified their foramen magnum meningiomas in the sagittal plane in clivo-spinal and spino-clival meningiomas. The authors advocated for clivo-spinal meningiomas a more lateral access after what we called vertebral artery transposition, which is vertebral artery unroofing from the C1 transverse process and medial retraction. They completed the access with partial occipital condyle drilling. For spino-clival meningiomas, the vertebral artery is not mobilized and no bone is drilled.

In fact, through a unique C-shaped lateral incision, they used what is called in the literature the antero-lateral or extreme-lateral approach for clivo-spinal meningiomas and the postero-lateral or far-lateral approach for spino-lateral ones.

In our experience, we limit the indication of the antero-lateral approach, which implies vertebral artery transposition, to rare selected cases of extradural meningiomas.

The postero-lateral approach is the only one we used for intradural meningiomas, whatever their cranio-caudal extension. One important concern with intradural foramen magnum meningiomas is the position of the lower cranial nerves. The authors have noted that clivo-spinal meningiomas are more difficult to resect than spino-clival ones because of the absence of a protecting arachnoidal plane between the tumor and vasculo-nervous structures. We have the same experience of increased surgical difficulty. This notion was introduced in our classification system of foramen magnum meningiomas (1) by localizing the position of the tumor according to the vertebral artery. In fact, the position of the lower cranial nerves can be anticipated when the tumor grows below the vertebral artery because the nerves are displaced together at the superior tumoral pole. Contrarily, tumors developed above or on both sides of the vertebral artery, even if they are “spino-clival” can push the lower cranial nerves separately in all directions, thereby precluding anticipation of their positions. For this reason, resecting the meningioma with preservation of lower cranial nerves integrity becomes technically more difficult, despite vasculo-nervous structures remain still protected by an arachnoidal plane.

We resect the bone of the foramen magnum lateral wall only for selected anterior meningiomas. In anterolateral meningiomas, we have found not necessary to widen the access by bone drilling since the surgical corridor is already enlarged between the anteriorly located bony structures of the foramen magnum lateral wall and the neuraxis displaced posteriorly and contralaterally by the tumor. For improving the access to some anterior foramen magnum meningiomas, resecting less than one fifth of the foramen magnum lateral wall is always sufficient. This tailored limited oblique drilling of the postero-medial corner of the occipital condyle, and the atlas allows the resection, respectively, of what the authors called “clivo-spinal” and “spino-clival” meningiomas.

Reference

1. Bruneau M, George B (2008) Foramen magnum meningiomas: detailed surgical approaches and technical aspects at Lariboisière Hospital and review of the literature. Neurosurg Review 31:19–33.

Armando Basso, Buenos Aires, Argentina

This is an excellent surgical descriptive study of Dr. Borba and colleagues. It has also a complete description of pre- and postoperative patient’s clinical status. We agree that posterior approaches give the best anatomical references and a good surgical road for complete resection of these tumors. Although, we prefer the hockey stick incision to prevent tissue debridement and the sitting position to get a less bloody operative field. We also use electrophysiological brainstem monitoring for this type of surgery.

The authors described an interesting neuroimaging classification of FM meningiomas which allowed them to make a decision about vertebral artery dislocation and condyle removal. All spinoclival types were completely respected and did not need condyle removal nor vertebral displacement during the approach; although some clivospinal anterior types have been approach without condyle removal either (cases 13 and 14). Tumor size alone was not a good predictive factor for surgical approach or for total resection, so we agree with the author that the approach should be tailored to each patient. We congratulate Dr. Borba et al. for surgical results of this difficult entity that shows a great knowledge and management of surgical anatomy.

Reference

1. De Oliveira E, Rhoton AL, Peace D. Microsurgical anatomy of the region of the foramen magnum. Surg.Neurol, 1985: 24: 293–352

Helmut Bertalanffy, Zürich, Switzerland

I wish to commend Borba and colleagues for the good results presented in this article. However, with a personal experience of over 40 patients operated on for foramen magnum meningioma, I wish to address two aspects related to the surgical management of these skull base tumors. One is the differentiation between “clivospinal” and “spinoclival” tumors mentioned by the authors. This is an artificial and old classification that, at least in my opinion, plays practically no role today. I wonder why the authors believe that the arachnoid plane separating the tumor from nerves and vessels is absent in “clivospinal” tumors. This may exceptionally be the case in any foramen magnum meningioma but is definitely not a common finding. Factors that directly influence the degree of difficulty of their surgical removal are the tumor size, the location, and particularly the extent of dural attachment, extension into the extradural compartment, tumor vascularity and consistency, previous surgery with residual tumor, and considerable adhesions between tumor and brainstem, as well as local anatomical details such as the size of the condylar emissary vein or the size of the jugular tubercle. The other aspect I wish to address is the discussion concerning the degree of occipital condyle resection. This is subject of many, not always logical, debates at congresses and has been discussed in many publications; I consider this the most misunderstood part of surgery around the foramen magnum. The amount of bone that should be removed is dictated by the underlying pathology. In the majority of foramen magnum meningiomas, it makes sense to first expose the tumor attachment located anteriorly or anterolaterally. Dura mater and tumor can then be coagulated at this level in order to first devascularize the tumor. Thereafter, piecemeal removal becomes significantly easier than without this exposure and vascular detachment. Tumors that extend as inferior as the spinal level C1 or even C2 may not only require partial (more or less extensive) condylar removal, but also resection of the medial portion of the lateral atlantal mass, lateral to the dural entrance of the vertebral artery, in order to expose the tumor attachment. Although this requires drilling of the medial aspect of the atlantoocipital joint, we have never encountered spinal instability after such a specific exposure. Certainly, it is mandatory for surgeons who perform this rather difficult surgical step to be thoroughly familiar with the local anatomy; additionally, they should well know how to manage (or better how to avoid) bleeding from the periarterial venous channels that surround the vertebral artery, and pay attention to local muscular or dural branches of this artery.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borba, L.A.B., de Oliveira, J.G., Giudicissi-Filho, M. et al. Surgical management of foramen magnum meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev 32, 49–60 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-008-0161-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-008-0161-5