Abstract

Background

Long COVID-19 may affect patients after hospital discharge.

Aims

This study aims to describe the burden of the long-term persistence of clinical symptoms in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review by using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline. The PubMed and Google Scholar databases were searched for studies that included information on the prevalence of somatic clinical symptoms lasting at least 4 weeks after the onset of a PCR- or serology-confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. The prevalence of persisting clinical symptoms was assessed and risk factors were described when investigated. Psychological symptoms and cognitive disorders were not evaluated in this study.

Results

Thirty-seven articles met the inclusion criteria. Eighteen studies involved in-patients only with a duration of follow-up of either less than 12 weeks, 12 weeks to 6 months, or more. In these studies, fatigue (16–64%), dyspnea (15–61%), cough (2–59%), arthralgia (8–55%), and thoracic pain (5–62%) were the most frequent persisting symptoms. In nineteen studies conducted in a majority of out-patients, the persistence of these symptoms was lower and 3% to 74% of patients reported prolonged smell and taste disorders. The main risk factors for persisting symptoms were being female, older, having comorbidities and severity at the acute phase of the disease.

Conclusion

COVID-19 patients should have access to dedicated multidisciplinary healthcare allowing a holistic approach. Effective outpatient care for patients with long-COVID-19 requires coordination across multiple sub-specialties, which can be proposed in specialized post-COVID units.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At the end of 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the pathogen responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. This virus caused an epidemic in China which then spread rapidly to other countries and continents worldwide and impacts all life aspects, including health, economy, and community life [1]. As of 23 January 2022, 352,323,862 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 5,615,210 deaths have been reported worldwide [2]. A variety of clinical manifestations has been observed in COVID-19 patients, ranging from asymptomatic presentation to critical forms with multiple organ failure and death [3, 4].The incubation periods of SARS-CoV-2 are in the range of 2–14 days after exposure to the transmissible sources, including direct contact, droplets, airborne, fomites, fecal–oral, and animal-to-human transmission. The early phase of the infection may be asymptomatic or characterized by upper and lower respiratory tract infection symptoms, including general symptoms, and frequently associated with taste and smell disorders or with gastro-intestinal symptoms. Some patients may present a sudden clinical worsening 7 to 10 days post onset of the symptoms, characterized by pneumonia symptoms that may be associated with thromboembolic complications. Finally, acute respiratory distress syndrome has been identified as a later phase in the acute evolution of SARS-CoV-2 [5]. In addition, COVID-19 has long-term consequences and complications even after hospital discharge [6], as previously observed with SARS-CoV-1 [7]. Because SARS-CoV-2 is an emerging pathogen, there is a lack of detailed information about the long-term persistence of symptoms in COVID-19 patients. Currently, there is no agreed definition of “long COVID.” It has been proposed to distinguish post-acute COVID (from 4 to 12 weeks after the onset of symptoms) and long COVID (more than 12 weeks post onset) [8, 9]. According to the definition proposed by the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), post-COVID-19 syndrome is defined by the persistence of symptoms for at least 12 weeks after onset [10]. In France, the French National Authority for Health has identified the long-term persistence of COVID-19 by the persistence of one or more initial symptoms for at least 4 weeks after onset, when none of these symptoms can be explained by another cause [11]. According to WHO, post COVID-19 case defined in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms onset persist at least two months without other reason for explaining [12]. In this review, we aim to give an overview of the prevalence of the long-term persistence of somatic clinical symptoms in discharged COVID-19 patients. We also describe the potential risk factors that have been identified so far.

Methods

Protocol and search strategy

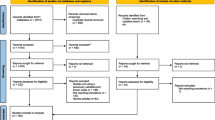

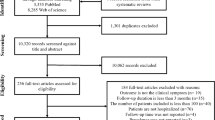

We conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline (http://www.prisma-statement.org). All relevant studies were identified by searching the following databases: PubMed (http://www.ncbi.mlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.fr). The current search was performed on 23 January 2022 by combining the key words:

-

# 1: “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”

-

# 2: “sequelae” OR “persistence” OR “persitant” OR “long-COVID” OR “long-haul COVID” OR “post-acute COVID syndrome” OR “persistent COVID-19” OR “long-hauler COVID” OR “post-acute sequelae” of “SARS-CoV-2 infection” OR “chonic COVID syndrome”

-

# 3: #1 AND #2

The keywords were identified by combining the synonym words and using MeSH terms in order to have an expanded comprehension of the literature.

Inclusion criteria

In this review, we included only articles written in English, with three criteria: (1) patients with a reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) confirmed COVID-19 infection (studies with only-serology-based diagnosis of COVID-19 were excluded from this review), (2) the reported prevalence of the persistence of clinical symptoms in COVID-19 patients after at least 4 weeks of follow-up post-onset, and (3) reporting on somatic clinical symptoms. Psychological and psychiatric disorders and memory, sleep, and attention disorders were not assessed in this study because we felt that such subjective symptoms may be either linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection itself or to the subjective perception of COVID-19 severity, due to the dramatic and pessimistic tone of public health communication in many countries and to the sometimes sensationalist media coverage of the epidemic that has prevailed until recently. For the same reasons, studies addressing only quality of life were not included. Data on persisting disorders obtained through laboratory investigations, imagery, or functional tests requiring specialized devices were not assessed in this study. Studies where only patients with persistent symptoms were followed-up (without a denominator) were excluded.

Both case reports and review articles were eliminated from the search, but the bibliographies of selected articles were used to find additional studies relevant for this review. We excluded studies conducted on animal subjects.

We assessed the quality of studies by using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [13] for cohort studies and NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies. NOS contains 8 items with 3 subscales and a total maximum score is 9. Studies quality ranged by score: good (7–9), fair (4–6), and poor (0–3) (Supplementary table 1 and 2).

Data collection process

After searching and manually removing duplicates, three researchers independently screened the abstracts to identify relevant articles. When there was a discordant result between the three researchers, a consensus meeting was conducted to discuss and reach an agreement. The full texts were then screened for selection or rejection in this review using the inclusion criteria.

The following data (if available) were extracted from each article: country where the study was conducted, study design, period of inclusion, number of participants, type of medical structure where patients were admitted, comparison group when available, demographic information, duration of follow-up, clinical findings at follow-up, proportion of patients lost to follow-up, and risk factors.

As a consequence of the diversity in patient populations and nature of the studies that have been carried out, a formal meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, the study results were summarized to give an overview of the long-term persistence of clinical symptoms in COVID-19 patient after an acute infection. When percentages were not presented in the articles, we performed the calculation from the available data.

The results of the review were divided into different paragraphs according to the duration of follow-up.

Results

General characteristics of studies

The search algorithm produced 9456 articles from the PubMed and Google Scholar databases (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 5452 articles were screened by reading their title and abstract. In total, 362 articles were processed for the full-text screening. Finally, we selected 37 articles (Table 1) which met the inclusion criteria for the qualitative analysis of the systematic review.

The studies which met the inclusion criteria are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

A total of 37 studies were included, 23 of which were conducted in Europe, including seven in Italy [14,15,16,17,18,19,20], four in France [21,22,23,24], three in Norway [25,26,27], two in Spain [28, 29], two in Germany [30, 31], one in Austria [32], one in Denmark [33], one in the Faroe Islands [34], one in Switzerland [35], and one in the UK [36]. Six studies were conducted in China [37,38,39,40,41,42], five in the United States (US) [43,44,45,46,47], two in Iran [48, 49], and one in Turkey [50]. The majority of the studies were conducted in a hospital setting and most were monocentric. In addition, one study conducted in Norway used laboratory recruitment and one national study was conducted in Denmark and in the Faroe Islands.

A total of 33 studies were conducted prospectively in cohorts of patients mostly through consultations or telephone interview [14, 15, 17, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 50], three studies were cross-sectional studies [16, 19, 48], and one was a retrospective cohort study [37]. Inclusion of patients at the acute phase took place in the first six months of 2020 for the majority of studies. The Danish and US studies ended in August 2020 [33, 44] and four studies ended in November 2020 [19, 29, 47, 49]; one Italian study ended in December 2020 [18].

A total of 9677 patients were included, with numbers by study ranging from 26 to 2685, with the mean age ranging from 11 to 73 years old and with the proportion of females ranging from 10 to 77%. Eighteen studies were conducted only among in-patients [14,15,16, 18, 22, 28,29,30, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 45, 48], eleven were conducted among in-patients and out-patients [19, 21, 23, 24, 27, 31, 32, 34, 44, 49, 50], and eight among out-patients only [17, 20, 25, 26, 33, 35, 46, 47]. Twenty-three studies included critically-ill patients, who required an oxygen therapy or admission to the ICU [14,15,16, 19, 20, 22, 24, 28, 31, 32, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 48,49,50]

Only three studies used non-COVID-19 patient comparison groups [26, 40, 47]. The proportion of patients lost to follow-up ranged from 4 to 73%, and in six studies this information was not provided [18, 19, 28, 44, 47, 49].

Twelve studies included follow-up that lasted from between 4 to less than 12 weeks (Table 1), nineteen studies lasted from 12 weeks to less than 6 months (Table 2), five studies lasted at least 6 months (Table 3), and one study with two times of follow-up (3–6 months and 6–12 months) [49]. Three studies exceeded after 1 year of follow-up [20, 31, 49].

In most studies, the overall persisting symptoms included general, neurological, respiratory, and cardiac symptoms. Some studies focused on specific symptoms such as taste and smell disorders, gastro-intestinal symptoms, or the impairment of physical activities, as evaluated by 2-min walking tests (short physical performance battery) [16].

Persistence of post-acute symptoms in studies with a follow-up of less than 12 weeks

A total of twelve studies were conducted with a follow-up of less than 12 weeks. Eight were conducted in Europe and four observed in the US.

Eight studies were conducted among in-patients only [14, 18, 19, 28, 30, 36, 43, 45] with the proportion of patients in the ICU and/or requiring mechanical ventilation ranging from 4.4 to 100%. In these eight studies, the most frequent symptoms persisting at 12 weeks were fatigue (31–64%) [14, 18, 28, 30, 36, 45], dyspnea (31–54%) [14, 15, 18, 28, 30, 36, 43], and arthralgia (22–55%) [14, 18, 43], although arthralgia was only assessed in two studies, and a dry or productive cough (5–46%) [14, 18, 28, 30, 36, 43].

Other relatively frequent persisting symptoms included thoracic pain/chest tightness (18–22%) [14, 30], ear, nose and throat-related symptoms (ENT) such as a sore throat (7–17%) [14, 30, 36], smell disorders (2–17%) [14, 15, 28, 30, 43], taste disorders (1–16%) [14, 15, 28, 30, 43], rhinitis (12–15%) [14, 30], dysphonia (20%) [36], swallowing problems (8%) [36], and general symptoms such as myalgia (1–22%) [14, 28, 30, 36, 43], or headache (9–15%) [14, 30, 43].

Persisting gastrointestinal symptoms were less frequently observed with diarrhea (3–9%) [14, 30, 43], anorexia (8%) [14, 36], nausea (6%) [30], stomach pain (3%) [30], ulcer (1%) [43], and dysphagia (8%) [36]. Persisting fever was rarely mentioned (1–3%) [30, 43].

Four studies were conducted in outpatients only or in populations of patients with a majority of outpatients [21, 35, 46, 47]. In these studies, persistent fatigue ranked first (12–84%) [35, 46, 47], while smell or taste disorders (4–74%) [46, 47], dyspnea (8–50%) [21, 35, 47], arthralgia (16–31%) [21, 46], cough (5–54%) [35], and thoracic pain/chest tightness (13–42%) [21, 47] were less prevalent than in studies conducted in in-patients. In addition, weight loss affected 17% patients in one study [21].

Risk factors were investigated in one study. In this study, the persistence of symptoms overall tended to be associated with older age, severity of symptoms at the acute phase, and abnormal auscultation at onset [21].

Persistence of symptoms in studies with a follow-up of between 12 weeks and 6 months

A total of twenty studies (Table 2) were conducted with a follow-up of between twelve weeks and six months (one study observed the persistence of symptoms at 3–6 month and 6–12 months [49]). Nine studies were conducted in Europe, six in China, one in Iran, and one in the US.

Nine studies [16, 22, 37,38,39,40,41,42, 48] were conducted among in-patients only, with the proportion of patients in the ICU and/or requiring mechanical ventilation ranging from 4 to 24%. In these studies, the most frequent symptoms persisting for 12 weeks to 6 months were fatigue (16–63%) [22, 37, 38, 40, 41, 48], dyspnea (15–61%) [22, 37, 38, 40,41,42], thoracic pain (5–62%) [22, 38, 40, 41], and a dry or productive cough (2–59%) [22, 37, 38, 40]. However, four studies addressing the persistence of thoracic pain/chest tightness [22, 38, 40, 41], its prevalence only ranged from 5 to 62%. The persistence of arthralgia was evaluated in only two studies, with a prevalence of 8% and 9% [40, 41].

Other relatively frequent persisting symptoms included related neurological-ENT (ear-nose-throat) symptoms with a smell disorder (6–13%) [22, 41, 42], taste disorder (4–11%) [22, 37, 41, 42], dysphonia (10%) [42], hearing problems (9%) [42], vision problems (8%) [42], swallowing problems (7%) [42], a sore throat (4%) [40, 41], and general symptoms such as hair loss (20–29%) [22, 40, 41], fever (< 1–20%) [38, 41], headache (2–18%) [37, 41], or sweating (24%) [40].

Persisting gastrointestinal symptoms ranged from 31 to 44% [38, 39], including diarrhea (5–26%) [38, 39, 41], anorexia (8–24%) [39, 41, 42], nausea (18%) [39], acid reflux (18%) [39], abdominal distension (14%) [39], vomiting (9%) [39], stomach pain (7%) [39], belching (10%) [39], discontinuous flushing (5%), and bloody stools (2%) [39].

Eleven studies were conducted in outpatients only or in a population of patients with a majority of outpatients [17, 19, 24, 25, 27, 32,33,34, 44, 49, 50]. In these studies, the persistence of dyspnea ranked first (8–37%) [17, 25, 27, 32,33,34, 44, 49, 50] while fatigue (11–42%) [17, 19, 33, 34, 44, 49, 50], thoracic pain (3–14%) [17, 19, 32, 34, 49, 50], and a persistent cough (4–17%) [17, 19, 25, 27, 32,33,34, 44, 49, 50] were less prevalent than in studies conducted in inpatients. Persistent arthralgia was reported in 7–18% of patients [17, 19, 25, 34, 49]. The persistence of related neurological-ENT symptoms was relatively frequent, including notably smell disorders (3–24%) [17, 19, 25, 27, 32,33,34, 49], taste disorders (2–17%) [17, 19, 25, 27, 33, 34, 49], and rhinitis (2–12%) [19, 25, 33, 34, 44].

Other persisting symptoms mentioned were general symptoms such as myalgia (7–24%) [17, 19, 25, 32, 34, 44, 49, 50], sweating (9–24%) [32, 49], alopecia/hair loss (12–17%) [44, 50], weight loss (3–9%) [19, 49, 50], and headache (6–12%) [17, 19, 25, 27, 33, 34, 44, 49, 50]. The persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms was rarely reported.

Risk factors were investigated in fourteen studies. The persistence of overall symptoms was associated with being female [24, 32, 33, 49], older [34], with a high body mass index [33], chronic respiratory disease [32], and a number of comorbidities and symptoms during the acute phase [25]. In one study, the persistence of at least two symptoms at follow-up was associated with dyspnea at the onset of symptoms [44]. Persistent fatigue was associated with troponin levels during the acute phase [38], and with being female [40, 41], while persistent dyspnea was associated with being female [27, 40,41,42] having increased levels of cholesterol, cancer [42], and the severity of initial symptoms [41]. The persistence of physical impairment was associated with admission to the intensive care unit and mechanical ventilation in one study [16]. In one study, persistent impaired cardiac function was associated with being female and having chronic respiratory disease [42]. Persistent hair loss was associated with being female in one study [40], while persistent muscle weakness was associated with being female and the severity of the initial symptoms [41]. Seven studies accessed the severity of illness at the acute phase and evidenced an association with symptoms persistence [17, 24, 27, 41, 42, 49, 50].

Persistence of symptoms in studies with more than 6 months follow-up

Only six studies were conducted with a follow-up time of more than six months (Table 3). Five of them were conducted in Europe and one in Iran.

One study was conducted among inpatients only [29], with a proportion of severe patients of 7%. In this study, the most frequent symptoms which persisted at eight months follow-up were fatigue (61%), dyspnea with activity (48%), dyspnea at rest (7%), thoracic pain (7%), palpitation (7), and cough (2%).

Five studies were conducted in outpatients only or in a population with a majority of outpatients [20, 23, 26, 31, 49]. In these studies, persistent fatigue ranked first (25–34%) [20, 26, 31, 49], while dyspnea (13–22%) [20, 26, 31, 49] was less frequent than in the only study conducted in inpatients. Other persisting symptoms which were mentioned were smell and or taste disorder (3–24%) [20, 23, 26, 31, 49] and a cough (2–13%) [20, 26, 31, 49]. Risk factors were investigated in four studies; females had more risk for symptoms persistence [20, 23, 31, 49].

Discussion

Eighteen studies were conducted in hospitalized patients with large variations in the prevalence of persisting symptoms, which is likely to be due to the heterogeneity in terms of patient demographics, disease severity at the acute phase, and the care provided. Fatigue (16–64%), dyspnea (15–61%), arthralgia (8–55%), cough (2–59%), and thoracic pain (5–62%) were the most frequent persisting symptoms. In nineteen studies conducted in outpatients or in population with a majority of outpatients, the persistence of these symptoms was less prevalent and 3–24% of patients reported prolonged smell and taste disorders (Table 5).

Risk factors were evaluated in twenty-one studies. The most common risk for symptom persistence were being female, older age, chronic respiratory disease, high body mass index (BMI), cancer, and the severity of COVID-19 at the acute phase.

Common limitations among the studies reviewed here include their small sample size and the risk of bias recall, notably during telephone interviews. Symptoms were frequently assessed without any validated objective scale or score. As an example, most of the articles assess dyspnea but do not mention its pulmonary or cardiac origin. Thus, there is a confounding factor between functional capacity, which could be fixed with rehabilitation programmes, and the presence of true impairment [41, 51, 52]. In addition, we could not conduct a meta-analysis to compare the characteristics of patients at baseline and at follow-up time due to heterogeneity of the data. Despite this limitation, the range of clinical signs that make up post-COVID syndrome seems to exist in substance, as shown by this comparative study evaluating general symptoms in 538 COVID-19 survivors compared to general symptoms in 184 patients without COVID, finding significant differences in post-COVID cardinal signs [40]. In addition, we excluded case reports which may have emphasized the occurrence of rare events, including stroke and dermatological symptoms.

Given the diversity of symptoms that could be attributed to long COVID, patients should have access to dedicated multidisciplinary healthcare allowing a holistic approach to be taken. The first step would be a robust assessment of the persistent symptoms reported by the patients, using screening questionnaires. Ideally, such questionnaires should be standardized so that the medical community could use the same tools making the results of the studies comparable. They should also be linked to a standardized physical screening evaluation.

Infectious disease specialists are not necessarily well-trained in evaluating subjective symptoms such as fatigue or insomnia, and would benefit from using clinical tools allowing such symptoms to be classified and quantified. Similarly, symptoms such as dyspnea, thoracic pain, or smell and taste disorders should be quantified using existing validated scales. In addition, depending on the symptoms, the standardized investigation of respiratory, cardiac, olfactory, and gustatory functions should be proposed to the patients including a full blood count, kidney and liver function tests, C-reactive protein tests, exercise tolerance tests, and imagery. The NICE guideline [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG188] proposes such an approach and could serve as a basis for such an approach. Other authors have proposed a potential approach to categorizing post-acute COVID-19 into three domains (persistent symptoms, organ dysfunction, and multisystem inflammatory syndrome), recognizing the potential interplay between organ pathology and symptomatology [53]. The pathophysiology and management of long COVID is currently an emerging field with little information available [8, 54]. Autonomic dysfunction, a chronic inflammatory and autoimmune response, has been proposed as a possible mechanism for long COVID [55], together with means of management [56] and pathological proof of SARS-CoV-2 presence in the vagus nerve structure [57]. Other authors propose that cognitive behavioral therapy may be an effective treatment for post-COVID fatigue syndrome [58]. Some authors proposed increasing fluid and salt, physical countermaneuvers, and adapted lifestyle for the postural orthostatic tachycardiac syndrome [55, 59]. Effective outpatient care for patients with long COVID-19 requires coordination across multiple subspecialties, which can be proposed in specialized post-COVID units [60]. Furthermore, sub-clinical or non-clinical assessment of multiple organ damage is now available with the help of 18F-FDG PET scans tools, which represent a relevant and modern technique to preventing unsuspected problems and explaining post-COVID or long COVID syndrome [61].

References

Gebru AA, Birhanu T, Wendimu E, Ayalew AF, Mulat S, Abasimel HZ et al (2021) Global burden of COVID-19: situational analyis and review. Hum Antibodies 29:139–148. https://doi.org/10.3233/HAB-200420

World Health Oragnization (2022) Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation report. [Accessed: 23/01/2022]

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Rodriguez-Morales AG, Méndez CA, Hernández-Botero S (2020) Tracing new clinical manifestations in patients with COVID-19 in Chile and its potential relationship with the SARS-CoV-2 divergence. Curr Trop Med Reports 7:75–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-020-00205-2

Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382:1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Gautret P, Million M, Jarrot PA, Camoin-Jau L, Colson P, Fenollar F et al (2020) Natural history of COVID-19 and therapeutic options. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 16:1159–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2021.1847640

Willi S, Lüthold R, Hunt A, Hänggi NV, Sejdiu D, Scaff C et al (2021) COVID-19 sequelae in adults aged less than 50 years: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis 40:101995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.101995

Zhong NS, Zheng BJ, Li YM, Poon LLM, Xie ZH, Chan KH et al (2003) Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People’s Republic of China, in February, 2003. Lancet 362:1353–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14630-2

Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS et al (2021) Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 27:601–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

Yong SJ (2021) Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis 53:737–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397

National Institue for Health and Care excellence (2020) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19

French National Authority for Healthh (2021) COVID long: les recommandation de la Haute Autorité de santé. Available from: https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/actualites/A14678

World Health Organization (2021) A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2000) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses

Carfì A (2020) Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 324:603–605. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12603

Monti G, Leggieri C, Fominskiy E, Scandroglio AM, Colombo S, Tozzi M et al (2021) Two-months quality of life of COVID-19 invasively ventilated survivors; an Italian single-center study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 65:912–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13812

Baricich A, Borg MB, Cuneo D, Cadario E, Azzolina D, Balbo PE et al (2021) Midterm functional sequelae and implications in rehabilitation after COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 57:199–207. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06699-5

Fortini A, Torrigiani A, Sbaragli S, Lo Forte A, Crociani A, Cecchini P et al (2021) COVID-19: persistence of symptoms and lung alterations after 3–6 months from hospital discharge. Infection 49:1007–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01638-1

Tosato M, Carfi A, Martis I, Pais C, Ciciarello F, Rota E et al (2021) Prevalence and predictors of persistence of COVID-19 symptoms in older adults: a single-center study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22:1840–1844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.07.003

Munblit D, Buonsenso D, De RC, Sinatti D, Ricchiuto A, Carfi A et al (2021) Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatr 110:2208–2211. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15870

Boscolo-Rizzo PB, Guida F, Polesel J, Marcuzzo AV, Capriotti V, D’Alessandro A et al (2021) Long COVID In adults at 12 months after mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.12.21255343

Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S et al (2021) Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.052

Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Le BA, Hamon A, Gouze H et al (2020) Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect 81:e4-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029

Nguyen NN, Hoang VT, Lagier J-C, Raoult D, Gautret P (2021) Long-term persistence of olfactory and gustatory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:931–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.021

Ghosn J, Piroth L, Epaulard O, Le Turnier P, Mentre F, Bachelet D et al (2021) Persistent COVID-19 symptoms are highly prevalent 6 months after hospitalization: results from a large prospective cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:1041 e1-1041 e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.012

Stavem K, Ghanima W, Olsen MK, Gilboe HM, Einvik G (2020) Persistent symptoms 15–6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study. Thorax 76:405–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377

Soraas A, Bo R, Kalleberg KT, Ellingjord-Dale M, Landro NI (2021) Self-reported memory problems eight months after non-hospitalized COVID-19 in a large cohort. JAMA Netw Open 4:10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18717

Blomberg B, Mohn K, Brokstad KA, Linchausen D, Hansen B-A, Jalloh SL et al (2021) Long COVID affects home-isolated young patients. Nat Med 27:1607–1613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01433-3

Antonio R-C, Diego MGJ (2021) Persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 infection: importance of follow-up. Med Clin (Engl Ed) 156:35–36

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Palacios-Ceña M, Rodríguez-Jiménez J, De-la-Llave-Rincón AI et al (2021) Fatigue and dyspnoea as main persistent Post-COVID-19 symptoms in previously hospitalized patients: related functional limitations and disability. Respiration 101:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518854

Daher A, Balfanz P, Cornelissen C, Müller A, Bergs I, Marx N et al (2020) Follow up of patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease sequelae. Respir Med 174:106197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106197

Seeßle J, Waterboer T, Hippchen T, Simon J, Kirchner M, Lim A et al (2021) Persistent symptoms in adult patients 1 year after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab611

Sonnweber T, Sahanic S, Pizzini A, Luger A, Schwabl C, Sonnweber B et al (2021) Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19: an observational prospective multicentre trial. Eur Respir J 57:2003481. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.03481-2020

Bliddal S, Banasik K, Pedersen OB, Nissen J, Cantwell L, Schwinn M et al (2021) Acute and persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 11:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92045-x

Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, Danielsen ME, Steig BÁ, Gaini S et al (2020) Long COVID in the Faroe Islands—a longitudinal study among non-hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 73:e4058–e4063. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1792

Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, Perone SA, Courvoisier D, Chappuis F et al (2021) COVID-19 Symptoms: longitudinal evolution and persistence in outpatient settings. Ann Intern Med 174:723–725. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5926

Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L et al (2021) Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol 93:1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26368

Zhao Y-M, Shang Y-M, Song W-B, Li Q-Q, Xie H, Xu Q-F et al (2020) Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. E Clin Med 25:100463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463

Liang L, Yang B, Jiang N, Fu W, He X, Zhou Y et al (2020) Three-month follow-up study of survivors of coronavirus disease 2019 after Discharge. J Korean Med Sci [Internet] 35:e418. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e418

Weng J, Li Y, Li J, Shen L, Zhu L, Liang Y et al (2021) Gastrointestinal sequelae 90 days after discharge for COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 6:344–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00076-5

Xiong Q, Xu M, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang J, Xu Y et al (2021) Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.023

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X et al (2021) 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 397:220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

Huang D, Chen C, Xuan W, Shuting P, Zhiwei F, Chen J, et al. (2020) Long-term outcomes and sequelae for 464 COVID-19 patients dischared from Leishan hospital in Wuhan, China. SSRN Electron J. Lancet preprint available at SSRN: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3739816

Jacobs LG, Paleoudis EG, Bari DL-D, Nyirenda T, Friedman T, Gupta A et al (2020) Persistence of symptoms and quality of life at 35 days after hospitalization for COVID-19 infection. PLoS One. 15:e0243882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243882

Jacobson KB, Rao M, Bonilla H, Subramanian A, Hack I, Madrigal M et al (2021) Patients with uncomplicated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have long-term persistent symptoms and functional impairment similar to patients with severe COVID-19: a cautionary tale during a global pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 73:e826–e829. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab103

Chopra V, Flander SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC (2020) Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 174:576–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5661

Cellai M, O’Keefe JB (2020) Characterization of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms in an outpatient telemedicine clinic. Open Forum Infect Dis 7:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa420

Graham EL, Clark JR, Orban ZS, Lim PH, Szymanski AL, Taylor C et al (2021) Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized Covid-19 “long haulers.” Ann Clin Transl Neurol 8:1073–1085. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51350

Simani L, Ramezani M, Darazam IA, Sagharichi M, Aalipour MA, Ghorbani F (2021) Prevalence and correlates of chronic fatigue syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder after the outbreak of the COVID-19. J Neurovirol 27:154–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-00949-1

Asadi-Pooya AA, Akbari A, Emami A, Lotfi M, Rostamihosseinkhani M, Nemati H et al (2021) Risk factors associated with long COVID syndrome: a retrospective study. Iran J Med Sci 46:428–36. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijms.2021.92080.2326

Kayaaslan B, Eser F, Kalem AK, Kaya G, Kaplan B, Kacar D et al (2021) Post-COVID syndrome: a single-center questionnaire study on 1007 participants recovered from COVID-19. J Med Virol 93:6566–6574

Tudoran C, Tudoran M, Pop GN, Giurgi-Oncu C, Cut TG, Lazureanu VE et al (2021) Associations between the severity of the post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and echocardiographic abnormalities in previously healthy outpatients following infection with SARS-CoV-2. Biology (Basel). 10:469. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10060469

Chilazi M, Duffy EY, Thakkar A, Michos ED (2021) COVID and cardiovascular disease: what we know in 2021. Curr Atheroscler Rep 23:37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-021-00935-2

Amenta EM, Spallone A, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, El Sahly HM, Atmar RL, Kulkarni PA (2020) Postacute COVID-19: an overview and approach to classification. Open forum infectious diseases. Oxford University Press US, Oxford, p 509. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa509

Silva Andrade B, Siqueira S, de Assis Soares WR, de Souza Rangel F, Santos NO, Dos Santos Freitas A et al (2021) Long-COVID and post-COVID health complications: an up-to-date review on clinical conditions and their possible molecular mechanisms. Viruses 13:700. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040700

Johansson M, Ståhlberg M, Runold M, Nygren-Bonnier M, Nilsson J, Olshansky B et al (2021) Long-Haul Post–COVID-19 Symptoms presenting as a variant of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Swedish experience. JACC Case Rep 3:573–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.01.009

Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, Torocastro M, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R et al (2021) Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med 21:e63–e67. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896

Lou JJ, Movassaghi M, Gordy D, Olson MG, Zhang T, Khurana MS et al (2021) Neuropathology of COVID-19 (neuro-COVID): clinicopathological update. Free Neuropathol 2:1–21. https://doi.org/10.17879/freeneuropathology-2021-2993

Vink M, Vink-Niese A (2020) Could cognitive behavioural therapy be an effective treatment for long COVID and post COVID-19 fatigue syndrome? Lessons from the qure study for Q-fever fatigue syndrome. Healthcare. 8:552. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040552 (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute)

Fedorowski A (2019) Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med 285:352–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12852

Santhosh L, Block B, Kim SY, Raju S, Shah RJ, Thakur N et al (2021) Rapid design and implementation of post-COVID-19 clinics. Chest 160:671–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.044

Guedj E, Campion JY, Dudouet P, Kaphan E, Bregeon F, Tissot-Dupont H et al (2021) 18 F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48:2823–2833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10096_2022_4417_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 24 KB) Supplementary 1. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of cohort studies

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, N., Hoang, V., Dao, T. et al. Clinical patterns of somatic symptoms in patients suffering from post-acute long COVID: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 41, 515–545 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-022-04417-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-022-04417-4