Abstract

Introduction

Alexander disease (AxD) is a rare leukodystrophy caused by dominant gain-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the astrocyte intermediate filament, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). However, there is an urgent need for biomarkers to assist in monitoring not only the progression of disease but also the response to treatment. GFAP is the obvious candidate for such a biomarker, as it is measurable in body fluids that are readily accessible for biopsy, namely cerebrospinal fluid and blood. However, in the case of ASOs, the treatment that is furthest in development, GFAP is the target of therapy and presumably would go down independent of disease status. Hence, there is a critical need for biomarkers that are not directly affected by the treatment strategy.

Methods

We explored the potential utility of biomarkers currently being studied in other neurodegenerative diseases and injuries, specifically neurofilament light protein (NfL), phosphorylated forms of tau, and amyloid-β peptides (Aβ42/40).

Results and Conclusions

Here, we report that GFAP is elevated in plasma of all age groups afflicted by AxD, including those with adult onset. NfL and p-tau are also elevated, but to a much lesser extent than GFAP. In contrast, the levels of Aß40 and Aß42 are not altered in AxD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alexander disease (AxD) is a rare leukodystrophy caused by dominant gain-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the astrocyte intermediate filament, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [13]. In all cases, the hallmark neuropathological feature is the formation of cytoplasmic protein aggregates in astrocytes known as Rosenthal fibres. A critical stage in the development of the disease seems to involve elevated levels of GFAP protein. This elevation is, in part, attributed to a positive feedback loop governing the regulation of GFAP expression. In this loop, the presence of the mutant protein triggers a stress response, leading to the transactivation of the GFAP promoter [8]. Studies using rodent models demonstrate that the suppression of GFAP expression, using antisense oligonucleotides (ASO), can not only prevent but even reverse the disease [5]. Based on these findings, a GFAP-targeted ASO has now moved into a combined phase 1–3 human clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04849741).

Despite being a single gene disorder, more than 100 GFAP variants have been associated with AxD, with little genotype–phenotype correlation. A wide range of clinical features have been observed, with ages of onset spanning prenatal through the ninth decades, and symptomatology reflecting forebrain, hindbrain, and/or spinal cord dysfunction along with considerable variation in life expectancy [15, 19]. Nevertheless, the prospect of ASO and other potential therapies highlights an urgent need for quantitative biomarkers to assist in monitoring not only the progression of disease but also the response to treatment. GFAP is the obvious candidate for such a biomarker, as it is measurable in body fluids that are readily accessible for biopsy, namely cerebrospinal fluid and blood. Previously, we found that GFAP is markedly elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with AxD and in blood of those with infantile and juvenile onset of symptoms (using a classification system based on age of first symptom) [7]. GFAP levels appeared unchanged in the blood of those with adult-onset disease. However, in the case of ASOs, the treatment that is furthest in development, GFAP is the target of therapy and presumably would go down independent of disease status. Hence, there is a critical need for biomarkers that are not directly affected by the treatment strategy.

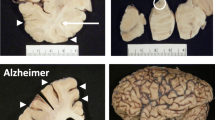

Other biomarkers for neurodegenerative injury and pathologies have been identified in blood in recent years [6]. Neurofilament light (NfL) protein is primarily a biomarker reflecting degeneration of myelinated axons and is regarded as a measure of the intensity of ongoing injury and stage of neurodegeneration [11]. Both CSF and blood levels of NfL are increased in most neurodegenerative and acute neurological disorders. In addition, phosphorylated tau (p-tau) and amyloid-β peptides (Aβ42/40) in blood have been shown to be important in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [6], both at the symptomatic and presymptomatic stages of the disease. Previous studies have implicated links between AxD and Alzheimer’s disease, both in terms of oxidative stress [3] and transcriptomic profiles of gene expression [4].

In this study, in addition to GFAP, we sought to determine whether these novel blood biomarkers might prove useful in AxD. Here, we report that GFAP is elevated in plasma of all age groups afflicted by AxD, including those with adult onset. NfL and p-tau are also elevated, but to a much lesser extent than GFAP. In contrast, the levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 are not altered in AxD.

Methods

Participants

Blood samples from AxD individuals (n = 49) and controls (n = 31) were the same as those analyzed previously in Jany et al. [7]. Briefly, AxD participation required genetic confirmation of the diagnosis by sequencing of the GFAP gene. This cohort contained those with neonatal (n = 3), infantile (n = 21), juvenile (n = 12), and adult onsets (n = 13), with 27 different variants distributed throughout the rod and tail domains of GFAP (see Supplemental Data for details of variants). Controls were unaffected healthy adults (≥ 18 years) of both sexes. Fresh samples of venous blood were collected into lavender-topped tubes that contained K2-EDTA as anticoagulant. The samples were centrifuged within 60 min of collection at 2500 g for 15 min at room temperature. The supernatant was immediately placed in a polypropylene tube and stored either on dry ice for shipping or at − 20 °C until shipping could be arranged. Upon arrival at the central laboratory, the samples were thawed, divided into aliquots, and stored at − 80 °C until further analysis. Three blood samples were collected as serum rather than plasma and were considered non-standard.

Blood biomarker measurements

All plasma biomarker measurements were performed using single molecule array (Simoa) technology on an HD-X platform at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, blinded to participant information. Plasma GFAP, NfL, Aβ42, and Aβ40 concentrations were measured using the commercial Neurology 4-plex E kit (#502,334, Quanterix, Billerica). Plasma p-tau181 and p-tau231 concentrations were measured using in-house Simoa assays developed at the University of Gothenburg [1, 9]. All measurements were done in singlicates on samples having undergone two free-thaw cycles and performed on one occasion using one batch of reagents. Intra-assay coefficients of variation on all biomarkers were < 15% derived from the internal control samples measured in duplicate on each analytical run. The three patient samples collected as serum were included in the analysis. Removing them from the study did not affect the results.

Statistical analysis

Data normality was determined by the D’Agostino-Pearson test, and statistical evaluation was performed on log10-transformed data. All data analysis reported has been performed on log10-transformed data, but the untransformed values are shown in descriptive tables and figures. A one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis) was performed to compare biomarker levels across groups adjusted for multiple comparisons. Correlations between the age of onset, age at collection, and between biomarkers were performed by Spearman’s rank correlation. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 (Armonk, NY, USA), and graphical representation was performed in Graph Pad Prism.

Ethics

Informed consents for studies of blood were obtained following protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and in accordance with the ethical standards from the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Results

The demographics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the control group was 34.6 years, whereas the mean ages of AxD patients (at the time when their samples were collected, though grouped by age of onset) were as follows: neonatal = 2.2, infantile = 6.6, juvenile = 19.9, and adult = 43.5 (all in years). The AxD group as a whole was balanced for sex, whereas the control group had a bias toward female participants.

Plasma levels of GFAP (Fig. 1a) were significantly increased in neonatal AxD (mean (SD); 7164 pg/mL (2126), P = 0.008), infantile AxD (12,191 pg/mL (10,158), P < 0.0001), and juvenile AxD (3705 pg/mL (3018), P < 0.001) compared with controls (70.6 pg/mL (38.1)). There was also a significant increase in adult AxD GFAP levels (774.1 pg/mL (550), P = 0.024). Plasma NfL (Fig. 1b) was increased in infantile AxD (106 pg/mL (130), P < 0.0001), juvenile AxD (21.1 pg/mL (9.6), P = 0.003), and adult AxD (24.6 pg/mL (29.6), P = 0.032) compared with controls (7.1 pg/mL (4.4)). The apparent change in NfL for neonatal AxD (26.37 pg/mL (13.4)) was non-significant. (Log scales for GFAP and NfL are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1).

Box and whisker plots demonstrating the concentrations of blood GFAP (A), NfL (B), pTau181 (C), pTau231 (D), Aβ42/40 (E), Aβ42 (F), and Aβ40 (G) in controls and AxD patients separated by age of onset. The age of onset classification boundaries are as in Jany et al. (2015) with the addition of the neonatal form (years): neonatal (0–0.08), infantile (0.08–2), juvenile (> 2–13), adult (> 13). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Plasma p-tau181 (Fig. 1c) and p-tau231 (Fig. 1d) demonstrated a similar pattern, with highest levels observed in infantile AxD (p-tau181, 28.9 pg/mL (15.1), P < 0.0001; p-tau231, 7.7 pg/mL (3.4), P = 0.001) compared with controls (p-tau181, 5.9 pg/mL (3.6); p-tau231, 4.3 pg/mL (2.0)). However, in contrast, p-tau181 was significantly increased in juvenile AxD (13.3 pg/mL (7.1), P = 0.003) compared to controls, which was not observed for p-tau231. Plasma Aβ42/40 (Fig. 1e) was unchanged across all groups, although Aβ42 (Fig. 1f) and Aβ40 (Fig. 1g) peptides were lowest for the adult AxD groups (Aβ42, 5.3 pg/mL (1.4), Aβ40, 99.2 pg/mL (26.3)).

There was a significant overall correlation between plasma GFAP and NfL (r = 0.533, P < 0.001), which had a slightly stronger association in AxD patients (r = 0.663, P < 0.001). All blood biomarkers had a negative association with age at collection in the AxD group (GFAP, r = − 0.766, P < 0.0001 (Fig. 2A); NfL, r = − 0.528, P < 0.0001 (Fig. 2B); p-tau181, r = − 0.613, P < 0.0001; p-tau231, r = − 0.381, P = 0.009; Aβ40, r = − 0.389, P = 0.006; Aβ42, r = − 0.395, P = 0.005). With respect to GFAP, it is interesting to note that the age at collection appeared to be a more important factor than the age of onset.

Discussion

We found significant changes in the levels of GFAP, NfL, and p-tau in the blood of individuals with AxD, especially those with infantile-onset AxD. This is the first study to show changes in plasma NfL, a biomarker associated with the intensity of neurodegeneration, in AxD. The higher levels of NfL in infantile-onset AxD are consistent with this group having shorter survival time and clinical manifestations of encephalopathy and epilepsy. Similarly, ours is the first study to show changes in p-tau, specifically p-tau181, in AxD. This biomarker is thought to be a specific biomarker for AD pathology [10], but AD is an unlikely scenario in the AxD patient group. One can speculate that p-tau181 is reflecting intensity of brain injury in AxD; however, the lack of correlation between NfL and p-tau181 in the juvenile AxD group suggests another mechanism, such as blood–brain barrier dysfunction. For GFAP, the results reported here differ from those reported in an earlier study [7], where adult-onset AxD individuals were indistinguishable from controls. In Jany et al. [7], however, GFAP quantitation was performed using a less sensitive sandwich ELISA in which 41% of the controls were not measurable. Using the Simoa platform, with an improved analytical sensitivity and wider dynamic range, the same samples now show that adult-onset patients have blood values that, as a group, are tenfold higher than controls.

Reactive astrocytes are a prominent feature in many of the leukodystrophies, and whether changes in CSF and/or blood levels of GFAP suggest utility as a biomarker for these conditions is just beginning as a topic for investigation. Recently, Beerepoot and colleagues [2] showed elevations in both GFAP and NfL in metachromatic leukodystrophy, although the degree of increase for GFAP was less than that seen in AxD. Of most significance was their finding that the degrees of elevation could distinguish slow vs. rapid rates of progression in the children with onsets before the age of 6 years. Changes in CSF and blood levels of GFAP and NfL have also been observed in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy [18].

Our study has several limitations. With regard to GFAP, Petzold [14] pointed out that none of the existing assays addresses potential differences in the expression of isoforms, post-translational modifications, cleavage products, or the hook effect as seen with other protein aggregates. In addition, without careful epitope mapping, the values for patients may be impacted by whether their individual variant affects assay performance, especially in those individuals with major deletions. Second, our study had imperfect age-matching between patients and controls (the latter limited by IRB requirements to be ⪰18 years). However, prior studies on the same analytes with similar methods in younger controls suggest that the current interpretations for the AxD data set are correct [16, 17]. For p-tau, concentrations are relatively high in newborns but become indistinguishable from adult levels in children over the age of 1 year, speaking against age being a major confounder when interpreting our results [12]. Third, we possessed limited clinical information on the AxD patients, thus preventing utilization of any classification system other than age of onset. Interesting differences may emerge when these biomarkers are evaluated in the context of the alternative systems proposed by Prust et al. [15] and Yoshida et al. [19]. Fourth, our results represent, for each patient, only a single point in time, and longitudinal studies that follow change over time will be extremely informative.

In conclusion, there is a need for easily obtainable biomarkers that can assist in monitoring disease progression and treatment response in AxD. Our novel results show that in addition to GFAP, blood biomarkers of neural injury (NfL) and tau (p-tau181) are changed in AxD, particularly those with infantile onset, and should be further examined in the wider context of AxD.

References

Ashton NJ, Pascoal TA, Karikari TK, Benedet AL, Lantero-Rodriguez J, Brinkmalm G, Snellman A, Schöll M, Troakes C, Hye A, Gauthier S, Vanmechelen E, Zetterberg H, Rosa-Neto P, Blennow K (2021) Plasma p-tau231: a new biomarker for incipient Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Acta Neuropathol 141:709–724

Beerepoot S, Heijst H, Roos B, Wamelink MMC, Boelens JJ, Lindemans CA, van Hasselt PM, Jacobs EH, van der Knaap MS, Teunissen CE, Wolf NI (2022) Neurofilament light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein levels in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Brain 145:105–118

Castellani RJ, Perry G, Brenner DS, Smith MA (1999) Alexander disease: Alzheimer disease of the developing brain? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 13:232–235

Gammie SC, Messing A, Hill MA, Kelm-Nelson CA, Hagemann TL (2024) Large-scale gene expression changes in APP/PSEN1 and GFAP mutation models exhibit high congruence with Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 19:e0291995

Hagemann TL, Powers B, Lin N-H, Mohamed AF, Dague KL, Hannah SC, Bachmann G, Mazur C, Rigo F, Olsen AL, Feany MB, Perng M-D, Berman RF, Messing A (2021) Antisense therapy in a rat model of Alexander disease reverses GFAP pathology, white matter deficits, and motor impairment. Sci Transl Med 13:eabg4711

Hansson O (2021) Biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Med 27:954–963

Jany PL, Agosta GE, Benko WS, Eickhoff JC, Keller SR, Köehler W, Koeller DM, Mar S, Naidu S, Ness JM, Pareyson D, Renaud DL, Schiffmann ESR, Simon J, Vanderver A, Eichler F, van der Knaap MS (2015) Messing A (2015) Cerebrospinal fluid and blood levels of GFAP in Alexander disease. Neuro 2:e0080-0015

Jany PL, Hagemann TL, Messing A (2013) GFAP expression as an indicator of disease severity in mouse models of Alexander disease. ASN Neuro 5(1):e00109. https://doi.org/10.1042/AN20130003

Karikari TK, Pascoal TA, Ashton NJ, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, Rodriguez JL, Chamoun M, Savard M, Kang MS, Therriault J, Schöll M, Massarweh G, Soucy JP, Höglund K, Brinkmalm G, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, Gauthier S, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, Rosa-Neto P, Blennow K (2020) Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. Lancet Neurol 19:422–433

Lantero Rodriguez J, Karikari TK, Suárez-Calvet M, Troakes C, King A, Emersic A, Aarsland D, Hye A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Ashton NJ (2020) Plasma p-tau181 accurately predicts Alzheimer’s disease pathology at least 8 years prior to post-mortem and improves the clinical characterisation of cognitive decline. Acta Neuropathol 140:267–278

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K (2017) Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 74:557–566

Mattsson N, Sävman K, Osterlundh G, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2010) Converging molecular pathways in human neural development and degeneration. Neurosci Res 66:330–332

Messing A, Brenner M (2020) GFAP at 50. ASN Neuro 12:1759091420949680

Petzold A (2015) Glial fibrillary acidic protein is a body fluid biomarker for glial pathology in human disease. Brain Res 1600:17–31

Prust M, Wang J, Morizono H, Messing A, Brenner M, Gordon E, Hartka T, Sokohl A, Schiffmann R, Gordish-Dressman H, Albin R, Amartino H, Brockman K, Dinopoulos A, Dotti MT, Fain D, Fernandez R, Ferreira J, Fleming J, Gill D, Griebel M, Heilstedt H, Kaplan P, Lewis D, Nakagawa M, Pedersen R, Reddy A, Sawaishi Y, Schneider M, Sherr E, Takiyama Y, Wakabayashi K, Gorospe JR, Vanderver A (2011) GFAP mutations, age of onset, and clinical sub-types in Alexander disease. Neurology 77:1287–1294

Simrén J, Andreasson U, Gobom J, Suarez Calvet M, Borroni B, Gillberg C, Nyberg L, Ghidoni R, Fernell E, Johnson M, Depypere H, Hansson C, Jonsdottir IH, Zetterberg H, Blennow K (2022) Establishment of reference values for plasma neurofilament light based on healthy individuals aged 5–90 years. Brain Commun 4:fcac174

Tybirk L, Hviid CVB, Knudsen CS, Parkner T (2023) Serum GFAP - pediatric reference interval in a cohort of Danish children. Clin Chem Lab Med 61:2041–2045

Weinhofer I, Rommer P, Gleiss A, Ponleitner M, Zierfuss B, Waidhofer-Söllner P, Fourcade S, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Reinert MC, Göpfert J, Heine A, Yska HAF, Casasnovas C, Cantarín V, Bergner CG, Mallack E, Forss-Petter S, Aubourg P, Bley A, Engelen M, Eichler F, Lund TC, Pujol A, Köhler W, Kühl JS, Berger J (2023) Biomarker-based risk prediction for the onset of neuroinflammation in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. EBioMedicine 96:104781

Yoshida T, Sasaki M, Yoshida M, Namekawa M, Okamoto Y, Tsujino S, Sasayama H, Mizuta I, Nakagawa M (2011) Nationwide survey of Alexander disease in Japan and proposed new guidelines for diagnosis. J Neurol 258:1998–2008

Funding

HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2022–01018 and #2019–02397), the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101053962, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-71320), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809–2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer’s Association (#ADSF-21–831376-C, #ADSF-21–831381-C, and #ADSF-21–831377-C), the Bluefield Project, the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2022-0270), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 860197 (MIRIADE), the European Union Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND2021-00694), the National Institute for Health and Care Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre, and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL (UKDRI-1003).

KB is supported by the Swedish Research Council (#2017–00915 and #2022–00732), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (#AF-930351, #AF-939721, #AF-968270, and #AF-994551), Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2017-0243 and #ALZ2022-0006), the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement (#ALFGBG-715986 and #ALFGBG-965240), the European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2019-466–236), the Alzheimer’s Association 2021 Zenith Award (ZEN-21–848,495), the Alzheimer’s Association 2022–2025 Grant (SG-23–1,038,904 QC), La Fondation Recherche Alzheimer (FRA), Paris, France, and the Kirsten and Freddy Johansen Foundation, Copenhagen, Denmark.

AM is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS110719; U54 NS115052) and the Juanma Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

NJA, GDM, and KT report no conflicts of interest.

KB has served as a consultant and is on advisory boards for Acumen, ALZPath, AriBio, BioArctic, Biogen, Eisai, Lilly, Moleac Pte. Ltd, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Prothena, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers; has served on data monitoring committees for Julius Clinical and Novartis; has given lectures, produced educational materials, and participated in educational programs for AC Immune, Biogen, Celdara Medical, Eisai and Roche Diagnostics; and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program, outside the work presented in this paper.

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZPath, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, Cognito Therapeutics, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Merry Life, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Alzecure, Biogen, Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Lilly, and Roche, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work).

AM has served on scientific advisory boards or as a consultant for Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ashton, N.J., Di Molfetta, G., Tan, K. et al. Plasma concentrations of glial fibrillary acidic protein, neurofilament light, and tau in Alexander disease. Neurol Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-024-07495-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-024-07495-8