Abstract

Background

During the Sars-CoV-2 virus pandemic, Italy faced an unrivaled health emergency. Its impact has been significant on the hospital system and personnel. Clinical neurophysiology technicians played a central role (but less visibly so compared to other healthcare workers) in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. This research aims to explore the experiences of clinical neurophysiology technicians during the pandemic and contribute to the debate on the well-being of healthcare workers on the front line.

Methods

We implemented a cross-sectional survey across Italy. It contained questions that were open-ended for participants to develop their answers and acquire a fuller perspective. The responses were analyzed according to the framework method.

Results

One hundred and thirty-one responses were valid, and the following themes were generated: technicians’ experiences in their relationship with patients, technicians’ relationship with their workgroup and directors, and technicians’ relationship with the context outside of their work. The first theme included sub-themes: fear of infection, empathy, difficulty, a sense of obligation and responsibility, anger, and sadness. The second theme contained selfishness/solidarity in the workgroup, lack of protection/collaboration from superiors, stress, and distrust. The last theme included fear, stress/tiredness, serenity, sadness, and anger.

Conclusion

This study contributes to building a humanized perspective for personnel management, bringing attention to the technical work of healthcare professionals in an emergency and the emotional and relational dimensions. These are the starting points to define proper, contextually adequate support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Italy was among the first countries in the world to face the unrivaled health emergency related to the Sars-CoV-2 virus pandemic. The impact of this has been significant on the hospital system and personnel [1, 2]. In this regard, many studies have observed the psychological sequela of the pandemic on Health Care Workers (HCWs) [3,4,5], particularly nurses [6, 7] and physicians [8, 9], during training [10, 11], within and outside hospital [12, 13].

Nonetheless, in their way and work contexts, many other professionals had to deal with the impact of the pandemic. Leaving their experience out of the picture would result in a non-comprehensive understanding of the implications of the pandemic. In particular, the literature addressing the experiences of technicians is scarce. To our knowledge, only a few studies investigated the experience of radiology technicians [14,15,16].

As for clinical neurophysiology technicians (CNTs), a gap in the research must be noted even though they played a central role (but less visibly so compared to other HCWs) in the health management of the COVID-19 pandemic. They immediately got involved in all the COVID-19 diagnostic processes related to COVID-19-positive patients. In this scenario, CNTs’ role mainly was in identifying neurological and neurophysiological virus’ secondary effects by performing electroencephalographic monitoring tests on COVID-19-positive patients in intensive care units [17, 18]. Concurrently, elective and “non-urgent” procedures, like neurophysiological exams, were suspended, with routine outpatient visits postponed. The continuity of care was not adequately ensured, locally [17] and internationally [19].

This research aims to explore the experiences of CNTs during the pandemic and contribute to the debate on the well-being of HCWs. Results may provide health managers and human resource supervisors with insights and practical implications to improve staff management.

Methods

We employed a descriptive qualitative design utilizing an online survey service (i.e., Google form) to address the study’s aim [20]. We found the qualitative methodology appropriate for the data collection of first-person perspectives on experienced phenomena, and we chose it over standardized scales measuring constructs already defined by the literature.

Questionnaire development and pilot

In May 2021, we set version 1 of the questionnaire on the Google platform, which was administered to a convenient sample for assessing its comprehensibility. To ensure clarity, readability, and appropriate length, seven CNTs participated in the pilot study. The participants commented on the structure and content of the survey and suggested modifications. After making some changes, the final version of the questionnaire was composed as follows:

-

Questions to collect sociodemographic and professional information (8 close-ended questions).

-

Six open-ended questions investigating three main issues: relationships with patients, relationships within the team and their group dynamics, and experience outside the work context.

Survey administration and participants’ recruitment

Participants were anonymously invited by posting the survey on social networks and through the Italian Association of Neurophysiology Technicians’ (AITN) mailing list. The target population was invited to complete it. At the beginning of the study, participants were provided with a written description of the study’s aim and the contact details of the principal investigators (GT and VM). Participation was voluntary. The questionnaire was available online from July 1 to August 31, 2021.

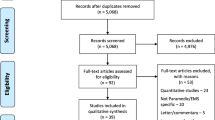

The software used for the survey returned a total of 133 respondents. The dataset was then cleaned of duplicate responses. The final dataset included n = 131 valid responses.

Data analysis

Responses to closed-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages.

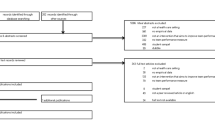

As for the text analysis from the open-ended questions, we applied the framework method [21, 22] according to an inductive (bottom-up) orientation (the content of the data directs theme developments) and a thematic approach [23]. We followed these steps:

-

We decided to focus the analysis on the following areas (triggered by the survey questions): the relationship with patients, the relationship with colleagues, and the context outside of work.

-

For each of those areas, F.S., G.T. F.F., and V.M. read a selection of responses to the open-ended questions.

-

Independently, the researchers generated three provisional analytical frames by labeling the responses and grouping the labels into themes.

-

The frameworks were discussed and compared in teams (L.G., F.S.). Disagreements between researchers were resolved through comparison, and a version for each frame was agreed upon.

-

The researchers (L.G., F.S.) then applied these analytical frames to the remaining data.

-

Any occurring changes made to the frames were discussed and endorsed by the team.

All the authors agreed on the last version of the findings.

Ethical considerations

The relevant Ethics Committee was approached. It was unnecessary to seek formal approval as the data was anonymous at source, in compliance with current privacy legislation (GDPR—Regulation 2016/679). However, the following suggestions were made:

-

To include the principal investigator’s contact details in case participants wanted to get in touch

-

To collect sociodemographic information by age range and avoid asking the municipality or province where the professionals were working, opting instead for the region

Participants were informed that by continuing to fill in the questionnaire, they consented to their data being processed by the researchers of the Qualitative Research Unit of the Azienda USL-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia. The software used for the survey returned anonymous responses labeled by timestamps. Researchers saved the dataset in a password-protected access location, assigning each respondent a numeric code.

Results

Study population

There were 131valid responses from participants, and their demographic information is shown in Table 1. The majority (31.3%) was aged 31–40, and 76.3% were female. The participants’ main work setting was public hospitals (87%).

Ninety-five respondents (75,5%) declared they had assisted COVID-19-positive patients during the pandemic, predominantly in sub-intensive or intensive care units.

Findings

Our analysis generated themes that provide insights into the experience of Italian CNTs during the COVID-19 pandemic. As for their relationship with patients, the participants reported a fear of being infected/infecting, empathy, difficulties in dealing with patients, a sense of obligation and responsibility, and sadness. Responses addressed the following themes with regard to the relationship with colleagues and directors: selfishness/solidarity in the workgroup, lack of protection/collaboration from supervisors, stress, and distrust. Finally, the extra-work context was described with several emotions (fear, stress/tiredness, serenity, sadness, anger), revealing that the emotional impact of working through the pandemic also affected personal and domestic life.

The technicians’ relationship with patients

For our participants, being there for their patients during the pandemic meant living their time at work in fear of being infected. CNTs reported experiencing this feeling in different situations, mostly while conducting examinations. They were also scared of infecting patients and of making their health conditions worse. In this context, greater attention was paid to keeping and maintaining physical distance than to the analyses.

CNTs reported they were having the same experience as patients: the pandemic was affecting everyone’s lives, pushing CNTs to try and help beyond their duty and to understand patients’ experiences. Participants reported feeling compelled to respond more promptly to patients’ needs and pain, to give greater importance to explaining the exam procedures, and to promote trust. CNTs thought they played an essential role in creating and maintaining a positive environment.

In this context, some participants reported that their relationships with patients improved because patients showed appreciation towards them. On the other hand, some participants described how their relationship with patients worsened as procedures got more complicated due to social distancing and the perceived lack of respect for the protective rules by the patients. Moreover, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) hindered successful communication.

In general, CNTs described an increased sense of obligation and responsibility towards patients: beyond the physical distance, they felt induced to pay more attention to equipment disinfection, using PPE, and performing examinations while leaving discouragement or fear out.

Many participants reported feelings of anger and sadness. According to them, sadness was due to witnessing the progression of patients’ symptoms, pain, isolation, and loneliness. Table 2 shows sub-themes and meaningful quotations from participants.

The relationship between colleagues and directors

Perceptions of working with colleagues were ambivalent. Some participants reported that the emergency provided an occasion for some “selfish” colleagues to take days off or pretend to be sick to stay at home. Already feeble relationships became more detached. On the other hand, other participants described that trust was strengthened within the workgroup. These respondents saw colleagues supporting each other by reorganizing shifts, sharing more personal experiences and emotions, and helping each other more than before during examinations.

Furthermore, the tone of the answers addressing CNTs’ relationship with directors and managers was dichotomic. Some participants felt superiors did not value the work and efforts that were being made (in some cases, they commented on ineffective management). On the other hand, some participants reported that they perceived there to be more comprehension and sympathy from superiors.

Finally, working in a team was considered more stressful than in the pre-pandemic period: participants expressed concerns, frustration, and psychological fatigue due to an increase in the workload combined with the risk of infection. We reported the sub-themes and meaningful quotations in Table 3.

The extra-work context

Most of the respondents described that they lived in fear and sadness at any time at home: fear of becoming infected and infecting loved ones, even losing them, of being sick alone, re-living the past difficult days of the pandemic, or dying.

The stress experienced at work continued at home for many of the participants: they disclosed that they were tired of the workload, disoriented, and forced to keep their distance from their loved ones with no psychological/emotional support.

For those respondents who could live with their families, a sense of serenity was reported: catching up for the lost hugs, being reassured/assuring their family members they were doing something useful for the entire community. In addition, receiving the anti-COVID-19 vaccine triggered feelings of hope.

Finally, some participants described that they were angry with citizens’ behaviors and non-compliance with social-health rules, interpreting them as a lack of respect for the infected persons and HCWs. Table 4 summarizes the sub-themes with participants’ meaningful quotations.

Discussion

Our analysis shed light on the multifaceted, emotional, less visible experiences of CNTs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The participants’ relationship with patients has changed significantly with impacts on the diagnostic processes given that they were involved in diagnosing neurological and neurophysiological virus’ secondary effects [24, 25]. During the pandemic, performing electroencephalographic monitoring tests on patients admitted to intensive care units assumed a different meaning. CNTs feared infection, aligning them to what other HCWs experienced [2]. They also experienced empathy in their relationship with patients due to the need to be more understanding towards patients’ needs and requests during exams and healthcare procedures.

The performance of outpatient examinations required special precautions in the emergency context, such as using PPE, maintaining physical distance, and the need to shorten the examination time. This led Italian CNTs to make an increased effort to create a welcoming atmosphere and foster trust with the patients. That experience is similar to what Liu et al. [3] have reported about healthcare providers’ experiences during the COVID-19 crisis in China: they made efforts to support the patients emotionally and not only to treat their disease.

On the other hand, this has led to difficulties for Italian CNTs in managing their relationship with patients and performing diagnostic exams. As reported in studies about radiographers’ and radiation therapists’ experience during the pandemic, infection control increased the time required for medical examinations and the complexity of procedures [16]. Furthermore, for HCWs with close relationship with patients — such as CNTs — the obstacles encountered were non-verbal communication and building empathic closeness. This emotional experience can be considered similar to that of other frontline HCWs, such as nurses [26].

Due to the pandemic, CNTs felt a sense of obligation and responsibility to maintain a physical distance from patients and to pay more attention to using PPE and to disinfect sanitary equipment in medical examinations. Several qualitative studies in the literature describe the experience of healthcare workers and technicians in relation to the shortage of PPE during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [9, 27]. In our study, CNTs reported the use of PPE and how that made it more difficult to relate to patients and carry out medical procedures. Indeed, the role of CNTs is very much involved in activities that require physical and empathic proximity to the patients. This could explain why several emotions were reported by Italian CNTs in their relationship with patients. Research participants also reported anger and sadness when referring to their relationship with patients during the pandemic because of some patients’ pain, isolation, loneliness, distrust, superficiality, and selfishness.

The second theme concerns CNTs’ relationship with their workgroup and superiors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This theme includes the following sub-themes: selfishness/solidarity in the workgroup, lack of protection/collaboration from directors, stress, distrust.

CNTs reported contrasting experiences regarding relationships among colleagues. On the one hand, they highlighted the selfishness of some colleagues, who took advantage of the emergency to defend personal interests (e.g., taking holidays). On the other hand, technicians described greater cohesion and trust between colleagues in the team. Italian CNTs also described opposite experiences regarding their relationships with managers. Some research participants reported an absence of protection from health managers, while others reported good cooperation with managers during the pandemic. These contrasting experiences are not dissimilar to what has emerged in the literature focusing on other healthcare roles: Bennett et al. [2] noted that some HCWs participating in their research reported supportive and cohesive relationships in the work team and with management. In contrast, others expressed a sense of being abandoned by management.

By what was expressed by the participants in our study, the literature describes the experience of HCWs who found the work team very supportive during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic: diagnostic radiographers participating in Naylor et al.’s research [15] spoke about “high morale, team spirit, and colleagues looking after one another.” To the best of our knowledge, nothing has been found in the literature about selfishness in the work team and HCWs’ experiences of distrust when describing the relationships between colleagues, except for studies related to COVID-19 vaccine-related decision [28].

The sub-theme concerning the work team’s increased stress is not new, particularly concerning the heavy workload that Italian CNTs and other healthcare workers have been facing. Many studies reported the overwhelming workload that HCWs have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic [29].

The third theme concerns the Italian CNTs’ experience outside their work context during the COVID-19 pandemic. This theme includes the following sub-themes: fear, stress/tiredness, serenity, sadness, and anger.

Just like fear refers to the possibility of infecting patients, CNTs experienced fear, indicating the possibility of infecting their family members and loved ones, losing them, or being alone or dying.

CNTs reported experiences of stress/tiredness, both physical and mental, characterizing the pandemic period. Their feelings are consistent with the pandemic fatigue [29] in HCWs’ experience, the emotional exhaustion reported by González-Gil et al. [26] on nurses, and the rollercoaster of emotions pointed out by Naylor et al. [15] on diagnostic radiographers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of our study’s findings that stands out is the participants’ experience of serenity and resilience. CNTs also experienced sadness in their non-work environment due to the uncertain situation, the need to isolate themselves, the loss of freedom, and the feeling of abandonment. HCWs’ similar experience is associated, in the literature, with uncertainty about the nature of the disease and their fear of possible transmission of the virus [29].

CNTs reported feeling anger about some citizens’ failure to comply with social and health rules. That experience is not dissimilar to what Sethi et al. [30] have reported about the impact of the pandemic on health professionals working in the hospital. HCWs had to deal with the indifferent attitude of the public and their non-compliance to simple rules, such as social distancing. The participants in our study consider indifference to show a lack of respect that affected those who worked in hospitals during the pandemic.

Undoubtedly, the pandemic has brought new needs to the surface for HCWs, including those who work in hospital settings. Given the complexity of emotions and reactions of the CNTs — on the question of balancing safety, collaboration with colleagues and managers, and daily life — specific psychological support intervention programs for HCWs are desirable. This would align with the World Health Organization’s urgent call for tailored and culturally sensitive mental health interventions [31]. A recent review [32] highlighted the urgency to create better connections between research and intervention programs. To define psychosocial support interventions, it is necessary to start with the needs and experiences of the HCWs. This study contributes to the evidence base.

Our study highlights the need to consider the emotional experiences of the CNTs to inform more functional management to prevent stress, isolation, and hostile feelings in work relationships and promote group cohesion.

Finally, considering the impact of reported sentiments and views on the quality and effectiveness of the work of the CNTs, in the long run, is a desirable relaunch of research. A qualitative study such as this one cannot measure such effects. Still, it can help explain why, if any, deviations in the quality and adequacy of clinical activities — compared to the pre-pandemic period — exist. For HCWs in general, much literature has provided preoccupying evidence in this regard: we know they experienced burnout [33], psychological burden [34], moderate to high work-related stress, and low to moderate resilience [35], low self-efficacy [36], to name a few. The emotional and psychological impact of caring for COVID-19-positive patients and, more generally, during the pandemic, on the professional and personal identity of HCWs has been widely studied. In the future, correlating this with CNTs’ work effectiveness and quality could broaden our understanding of the effects of an unprecedented emergency experience.

References

Sanghera J, Pattani N, Hashmi Y et al (2020) The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting—a systematic review. J Occup Health 62:e12175. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12175

Bennett P, Noble S, Johnston S et al (2020) COVID-19 confessions: a qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ Open 10:e043949. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043949

Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE et al (2020) The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health 8:e790–e798. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7

Chigwedere OC, Sadath A, Kabir Z, Arensman E (2021) The impact of epidemics and pandemics on the mental health of healthcare workers: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:6695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136695

DanetDanet A (2021) Impacto psicológico de la COVID-19 en profesionales sanitarios de primera línea en el ámbito occidental. Una revisión sistemática. Med Clínica 156:449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.11.009

Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E et al (2020) Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud 111:103637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637

Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D et al (2021) Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 77:3286–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14839

Aughterson H, McKinlay AR, Fancourt D, Burton A (2021) Psychosocial impact on frontline health and social care professionals in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 11:e047353. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047353

Nyashanu M, Pfende F, Ekpenyong M (2020) Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care 34:655–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425

Canet-Vélez O, Botigué T, Lavedán Santamaría A et al (2021) The perception of training and professional development according to nursing students as health workers during COVID-19: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract 53:103072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103072

Barisone M, Ghirotto L, Busca E et al (2022) Nursing students’ clinical placement experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic: a phenomenological study. Nurse Educ Pract 59:103297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103297

Xu H, Stjernswärd S, Glasdam S (2021) Psychosocial experiences of frontline nurses working in hospital-based settings during the COVID-19 pandemic - a qualitative systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv 3:100037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100037

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T et al (2020) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 88:901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

Lewis S, Mulla F (2021) Diagnostic radiographers’ experience of COVID-19, Gauteng South Africa. Radiography 27:346–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.009

Naylor S, Booth S, Harvey-Lloyd J (1995) Strudwick R (2022) Experiences of diagnostic radiographers through the Covid-19 pandemic. Radiogr Lond Engl 28:187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2021.10.016

Shanahan MC, Akudjedu TN (2021) Australian radiographers’ and radiation therapists’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Radiat Sci 68:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmrs.462

Assenza G, Lanzone J, Ricci L et al (2020) Electroencephalography at the time of Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol 41:1999–2004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04546-8

Rifino N, Censori B, Agazzi E et al (2021) Neurologic manifestations in 1760 COVID-19 patients admitted to Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy. J Neurol 268:2331–2338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10251-5

García-Azorín D, Seeher KM, Newton CR et al (2021) Disruptions of neurological services, its causes and mitigation strategies during COVID-19: a global review. J Neurol 268:3947–3960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10588-5

Braun V, Clarke V, Boulton E et al (2020) The online survey as a qualitative research tool. Int J Soc Res Methodol 24:641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E et al (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N (2000) Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 320:114–116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) Thematic analysis. A practical guide. SAGE Publications, London

Taquet M, Sillett R, Zhu L et al (2022) Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients. Lancet Psychiatry 9:815–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00260-7

Guadarrama-Ortiz P, Choreño-Parra JA, Sánchez-Martínez CM et al (2020) Neurological aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection: mechanisms and manifestations. Front Neurol 11

González-Gil MT, González-Blázquez C, Parro-Moreno AI et al (2021) Nurses’ perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 62:102966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102966

Kurotschka PK, Serafini A, Demontis M et al (2021) General practitioners’ experiences during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a critical incident technique study. Front Public Health 9:623904. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.623904

Ghirotto L, Díaz Crescitelli ME, De Panfilis L et al (2022) Italian health professionals on the mandatory COVID-19 vaccine: an online cross-sectional survey. Front Public Health 10:1015090. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1015090

Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C et al (2021) Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Am J Infect Control 49:547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001

Sethi BA, Sethi A, Ali S, Aamir HS (2020) Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals: impact of COVID-19 on health professionals. Pak J Med Sci 36(COVID19-S4):S6–S11. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2779

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH et al (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7:547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Buselli R, Corsi M, Veltri A et al (2021) Mental health of health care workers (HCWs): a review of organizational interventions put in place by local institutions to cope with new psychosocial challenges resulting from COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 299:113847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113847

Ulfa M, Azuma M, Steiner A (2022) Burnout status of healthcare workers in the world during the peak period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 13:952783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952783

Maunder RG, Heeney ND, Kiss A et al (2021) Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital workers over time: relationship to occupational role, living with children and elders, and modifiable factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 71:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.04.012

Al Hadid LAE, Al Barmawi MA, Alnjadat R, Farajat LA (2022) The impact of stress associated with caring for patients with COVID-19 on career decisions, resilience, and perceived self-efficacy in newly hired nurses in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep 5:e899. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.899

Simonetti V, Durante A, Ambrosca R et al (2021) Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a large cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs 30:1360–1371. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15685

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This is an observational study. The AVEN Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Informed consent

The participants were informed that by continuing to fill in the questionnaire, they would be giving their consent to data processing by the researchers of the Qualitative Research Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia (Italy).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sireci, F., Bellei, E., Torre, G. et al. Being a technician during COVID-19: a qualitative cross-sectional survey on the experiences of clinical neurophysiology technicians. Neurol Sci 44, 429–436 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06551-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06551-5