Abstract

The novel member of coronaviruses family, severe acute respiratory coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), with high structural homology to SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS) has spread rapidly with about 20 million cases infection and over 700,000 deaths. SARS-CoV-2 has been emerged as a worldwide disaster due to non-specific few respiratory and gastrointestinal manifestations at the onset of disease as well as long incubation period. Surprisingly, not only respiratory failure but also the underlying coagulation disorder and neurovascular involvement worsen the clinical outcome of infected patients. In this review article, we describe the probable mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infection and stroke occurrence. We will also discuss the cerebrovascular events following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the recommended therapies, and future prospects to better manage these patients in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or the severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has initially originated from Wuhan city of China in December 2019 with suspicious unusual pneumonia symptoms [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [2]. SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped β-type novel coronavirus with a single-strand, positive-sense RNA genome consisting of 29,000 nucleotide bases in length [3]. On the basis of latest recognized SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis, this four-part virus (the envelope, membrane, spike, and nucleocapsid protein) invades the cells through the spike protein binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [4]. ACE2 is a widespread distributed receptor on the cellular surface of multiple organs including endothelial and neural cells [4]. COVID-19 is mainly transmitted through respiratory droplets and contact, stool, and prolonged exposure to aerosols in a closed environment with incubation period from 3 to even 38 days in some cases [3]. The most constitutional symptoms at the onset of disease consists of fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, sore throat, fatigue, malaise, diarrhea, dyspnea, headache, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multiorgan dysfunction [5]. Although most patients with COVID-19 have mild-to-moderate constitutional symptoms, approximately 15% experience severe pneumonia, 5% suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and about one-third present neurological symptoms [6, 7]. In this regard, raising reports are indicating the involvement of skeletal muscle (presenting with myalgia and serum creatine kinase elevation), peripheral nervous system (the impairment of taste, smell, and vision, Guillain-Barré syndrome, neuralgia, and polyneuropathy), and central nervous system (from mild non-specific symptoms including dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, languidness, myalgia to advanced complex manifestations such as cerebrovascular disease, acute encephalitis, meningitis, ataxia, epilepsy, and consciousness impairment) [7,8,9,10].

Growing evidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke regarding COVID-19-induced coagulopathy is being published. The considerable point is that most patients are younger, with large vessel multiple distribution occlusion, more severe strokes, and developed by mobile fragile clots resistant to fibrinolysis or hard to mechanical thrombectomy [11]. Although the hypercoagulability state especially in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to COVID-19 necessitates to higher anticoagulation targets in comparison to other ill patients [12], adverse bleeding events make anticoagulation management as a controversy challenge. On the other hand, recent evidence displays a 2.5-fold increase in odds of severe COVID-19 illness in individuals with a past medical history of cerebrovascular disease without significant increase in odds of mortality [13]. It is clear that better recognition of underlying COVID-19-induced hypercoagulability state mechanisms efficiently helps to target specific interferer agents and better management of the disease.

In this review article, we summarize the SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis, hypercoagulability state induction, reported cerebrovascular events following COVID-19 infection, clinical approaches, and recommended solutions to manage stroke in COVID-19 cases.

Neuropathology of SARS-CoV-2-induced cerebrovascular ischemia

There are different ischemic/non-ischemic neuropathological mechanisms which seriously can damage the nervous system. Of note, as SARS-CoV-2 is a member of coronavirus family with high structural and infection resemblance, similarity in neuropathologic mechanism is foresighted [14]. To clarify the role of inflammation and secondary organ damage, progression paradigm of disease is generally divided into 3 distinct phases:

Stage I as early infection phase

In this phase, SARS-CoV-2 infiltration to the lung parenchyma and its proliferation is occurred. Immune response is characterized by monocytes and macrophages infiltration (Fig. 1).

Lung alveolus in phases I and II. SARS-CoV-2 enters into type II alveolar epithelial cells via TMPRSS2 or ACE2 receptors. After viral replication and proliferation, immune response is initiated by monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. Then at phase III, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2, 6, 7, TNF-α, and IFN-γ induce the cytokine storm and systemic inflammation. Lung parenchymal injury is occurred following inflammatory processes, vasodilation, endothelial permeability, leukocyte recruitment, and pulmonary edema. Lung vascular endothelium destruction by direct SARS-CoV-2 entrance and induced inflammation can predispose microthrombus formation and lung infarction

Stage II as pulmonary phase

Collateral tissue injury, vasodilation, endothelial permeability, and leukocyte recruitment are occurred following the inflammatory processes (Fig. 1).

Stage III as hyperinflammation phase

This phase is characterized with host worsening inflammatory response even with diminishing viral load (Fig. 2).

SARS-CoV-2 directly induces the endothelial cell death in the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The tight junctions in endothelial cells are destructed through monocytes, neutrophils, IL-1β, and TNF-α. In addition to underlying coagulopathy, the basement membrane and Von-Willebrand factor (VWF) contiguity with platelets and RBCs facilitate thrombus formation. The developed thrombus in the brain or other origins such as cardiac thrombus or deep vein thrombus can potentially embolize to distal parts or other branches. Hypoxia-induced vasodilation besides endothelial damage makes the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 dissemination to brain parenchyma or cerebrospinal fluid. High thrombin level due to low protein C, antithrombin III, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor amplifies the function of proteinase-activated inhibitor 1 (PAR-1) receptors which is led to inflammation. AT-III, antithrombin III; Pro C, protein c; TFI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor

However, most cases are mild or asymptomatic and significant overlap among phases can be observed, but some patients develop mild constitutional symptoms, respiratory distress, hypoxemia, and cardiovascular involvement. Retrospective studies on non-survivors and critically ill patients, more than ever, highlight lymphocytes’ (especially CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells) high vulnerability to destruction and viral infection. Maybe for this reason, by disease worsening, progressive lymphocytopenia is detected in laboratory surveys [15, 16]. Some evidence also supports lymphocytopenia correlation with cytokine storm [17].

SARS-CoV-2 potentially can develop both arterial and venous thromboembolism. Recent pandemic outcomes point to SARS-CoV-2-induced thrombocytopenia (36.2%), and D-dimer elevation (46.4%), while these rates increase to 57.7% and 59.6%, respectively, in patients with severe COVID-19 disease [18]. The COVID-19-induced coagulopathy is commonly initiated with prominent D-dimer and fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products while prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet counts abnormalities seem to be rare in initial presentations [19]. Thrombin generation is regulated by negative feedback loops and physiological anticoagulants, such as the protein C system, antithrombin III, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Besides thrombin function on clot formation by activating platelets and converting fibrinogen to fibrin, it can amplify the inflammation via proteinase-activated receptors (PARs), principally PAR-1. Reduced anticoagulant concentrations impair control mechanism during inflammation [20]. Platelet intermediation and coagulation cascade overactivation with procoagulant and anticoagulant imbalance through viral induction of systemic inflammatory response develop intra-alveolar or excessive systemic fibrin clots formation, microthrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure [18]. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture due to local inflammation, cytokine storm response, diffuse intravascular coagulation, and hypoxia might be predisposing factors of arterial thromboembolism and large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke [21].

A hallmark of severity exaggerated the systemic inflammation or cytokine storm existing in third phase of acute illness. Some inflammatory markers have been highly detected in advanced stage of critically ill patients leading to multiorgan failure, including IL (interleukin)-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-12, TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-α, IFN-γ, IP (inducible protein)-10, MCP (monocyte chemoattractant protein)-1, MIP (macrophage inflammatory protein)-1α, G-CSF (granulocyte-colony stimulating factor), CRP (c-reactive protein), procalcitonin, and ferritin [6, 17, 22].

In addition to pulmonary dysfunction, subsequent alveolar destruction, and pulmonary circulation microthrombosis, SARS-CoV-2 could result in central hypoxia through targeting respiratory center in the brainstem which extremely worsen respiration and oxygen metabolism [23]. Besides reduction in overall oxygen supply, the oxygen demand increases due to higher anaerobic metabolism, cerebral vasodilation, pulmonary vasoconstriction, and unstable hemodynamics [8].

Cardiac embolization due to virus-related cardiac injury occurs in 20–30% of hospitalized patients [24]. Indirect cardiac injury without viral infiltration, namely, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy with elevated cardiac injury biomarkers and electrocardiographic abnormalities, hints the heart as a target of systemic inflammation [25,26,27]. An average 8–12% incidence of acute cardiac injury reported by Lippi and Plebani declared that not only systemic inflammation but also direct myocardial injury, myocardial oxygen demand supply mismatch, acute coronary events, and iatrogenicity could harm cardiac function [28]. One theory of direct myocardial dysfunction may relate to SARS-CoV-2-induced ACE2 downregulation [29].

Although antiphospholipid antibodies may rarely induce thrombotic events, there are supporting evidence about the role of antiphospholipid antibodies in development of ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients [30, 31]. In a 6-patient case series, Beyrouti et al. reported positive lupus anticoagulant in 5 patients while one had medium-titer IgM anticardiolipin and low-titer IgG and IgM anti β2-glycoprotein-1 antibodies [32]. Additionally, Zhang et al. claimed positive anticardiolipin IgA, anti β2-glycoprotein I IgA, and IgG correlation with extensive multiple cerebral infarctions in 3 critically ill COVID-19 patients [30]. Perhaps SARS-CoV-2 via unknown pathogenesis stimulates antiphospholipid antibody overproduction [32]. However, in such critically ill patients, it is not that easy to differentiate antiphospholipid antibody–induced ischemia from other differential diagnosis resulting to multifocal thrombosis.

Overall, it seems that SARS-CoV-2 could simulate a Virchow triad-like condition through blood flow stasis especially in immobilized ill patients, underlying coagulopathy predisposition, and endothelial damage by direct destruction or systemic inflammation.

Cerebrovascular manifestations of SARS-CoV-2

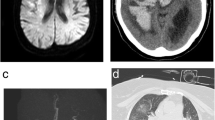

Since the time SARS-CoV-2 appeared in Wuhan, several reports have shown brain and spinal cord infections in some patients. In a retrospective, observational case series reported by Avula A et al., four patients referred to emergency department (ED) with synchronous respiratory and neurologic complaints as altered mental status, unilateral facial drop, slurred speech, aphasia, hemineglect, unilateral weakness and numbness, and hemiplegia. More imaging and laboratory surveys revealed the concurrent ischemic stroke and COVID-19 infection. Patients were not candidate for thrombolysis or neuro-intervention during hospitalization [33]. A case series of 6 ischemic stroke patients was reported by Beyrouti et al. in 2020. Regarding disease severity, 4 cases were severe (with one death) while 2 cases were moderate. Even though therapeutic anticoagulation and multiterritory infarcts were detected in 3 patients, 2 cases had synchronous venous thrombosis and 2 cases developed ischemic stroke. In the laboratory findings, high D-dimer level (all cases), hypoalbuminemia (all cases), high lactate dehydrogenase (all cases), high serum ferritin (5 of 6 cases), high c-reactive protein (CRP) (5 of 6 cases), positive lupus anticoagulant (5 of 6 cases), anemia (5 of 6 cases), high fibrinogen level (4 of 6 cases), high cardiac troponin I (4 of 6 cases) lymphopenia (3 of 6 cases), high prothrombin time (3 of cases), and thrombocytosis (2 of 6 cases) were detected [32]. Hughes et al. reported a 59-year-old man presented with fever and a 4-day history of gradual progressive right-sided fronto-temporal headache. Laboratory surveys showed active COVID-19 infection; moreover, an increase in inflammatory markers and fibrinogen level and decrease in activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) were observed. Besides CT scan findings, CT venogram filling defects in the right sigmoid and transverse sinus confirmed cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [34]. In a case series of stroke occurring in 19 patients with COVID-19 infection from Italy, seventeen cases (89.5%) were ischemic and 2 others remaining were hemorrhagic (10.5%). Immovilli et al. reported the stroke incidence about 2.2% among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Stroke etiologies include large artery atherosclerosis, cardio-embolism, small vessel disease, and undetermined factors [40]. Gonzalez-Pinto et al. reported malignant ischemic stroke in a 36-year-old woman. The patient was found with altered level of consciousness, global aphasia, and right hemiplegia. Further investigations demonstrated COVID-19 infection with significant infarct in the territory of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) with mild midline deviation. Patient’s clinical status was not suitable for any other procedures, and finally, she passed away [35]. In a case series by Al saiegh et al., 2 patients pretended with neurological symptoms as sudden onset headache, mental status change, hemiparesis, and aphasia with real-time PCR positive results for SARS-CoV-2. Despite positive real-time PCR of nasal sample, SARS-CoV-2 real-time PCR for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was negative for 2 consecutive times [36]. In a recent case report, Viguier et al. presented a 73-year-old man who developed an acute ischemic stroke after a week history of fever and dry cough. On admission, the patient had right-sided hemiparesis with aphasia. Head and cervical CT angiography revealed a large floating thrombus appended to a non-stenosing plaque on the left common carotid artery wall. Head CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed acute ischemic stroke in the left common carotid artery territory. Patient was undergone anticoagulation with low molecular heparin (enoxaparin b.i.d). After 15 days on follow-up with ultrasound examination, there were no recurrent emboli and previous thrombus but a moderate aphasia persisted [37]. Oxley et al. reported consecutive 5 patients aging younger than 50 years old with ischemic stroke diagnosis referring in a 2-week period from March 23 to April 7, 2020. Surprisingly, all mentioned patients developed large vessel involvement with various clinical presentations as altered level of consciousness, headache, horizontal gaze, homonymous hemianopia, ataxia, unilateral hemiplegia, dysphasia, dysarthria, and sensory deficit. All patients’ nasal swab PCR were positive for SARS-CoV-2, while just 2 out of 5 cases developed respiratory symptoms. Mild-to-moderate systemic coagulopathies were detected in laboratory findings of 4 patients [38]. An observational study on 184 critically ill intensive care unit (ICU) admitted patients with proven SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia showed an incidence of 31% thrombotic complications. Despite standard thromboprophylaxis measures, 81% developed pulmonary embolism (PE), 21% diagnosed with venous thrombotic events (VTE), and arterial thrombotic events in 3.7% of patients. Age and coagulopathy were independent predictors of thrombotic events [41]. Yeboah and colleagues published a case report of a 49-year-old woman with the complaint of fever, fatigue, and progressive shortness of breath. Laboratory findings showed CRP, lactate dehydrogenase, procalcitonin, and ferritin elevation. At the second day of admission, she developed sudden left-sided hemiparesis, sensory neglect, left hemianopsia, and right gaze deviation with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) 14. The CT angiography and CT perfusion showed thrombus in the right carotid artery and filling defect in left carotid artery bulb. Patient was gone under treatment with alteplase, mechanical thrombectomy, and retrievable stent appliance in the right cerebral artery. NIHSS alleviated to 0 at discharge and due to thrombus in the left cerebral artery, a 6-month course of apixaban is recommended [39]. Belani et al. in a retrospective case-control study on 41 cases with imaging evidence of acute infarction and 82 controls of 6 New York City hospitals displayed 43% of case concurrent COVID-19 infection while 18.3% of control COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 had a significant independent association with acute ischemic stroke (OR = 3.9, 95% CI, 1.7–8.9; P = 0.001) [42]. They recommended more aggressive monitoring for stroke in COVID-19 patients [42]. A single-center, prospective observational study 6 weeks after COVID-19 pandemic declared a mean fall of 38% in new stroke diagnosis with similarity in monthly new large vessel occlusions (LOVs) strokes, while the proportion of new LVOs doubled approximately [43]. Table 1 summarizes the recent evidence about SARS-CoV-2 and stroke incidence.

Clinical approach and recommended therapies

Previous evidence indicates that patients with sepsis developing coagulopathy are more likely to multiorgan failure and high mortality rate [44, 45]. Coagulation screening test such as measurement of D-dimer, fibrinogen levels, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet counts in initial suspected venous thromboembolism (VTE) or pulmonary embolism (PE) presentation should be considered [19]. Tang et al. reported D-dimer level of 2.12 μg/mL (range 0.77–5.27 μg/mL) in the non-survivors while it was significantly higher than the survivors with level of 0.61 μg/mL (range 0.35–1.29 μg/mL) with the lab normal ranges of < 0.50 μg/mL [46]. Additionally, Huang et al. pointed higher D-dimer level (median D-dimer level 2.4 mg/L [0.6–14.4]) in critically ill patients than who were not (median D-dimer level 0.5 mg/L [0.3–0.8], P = .0042) [22]. Accordingly, D-dimer must consider as a hospital admission factor independent to other severe symptoms. Despite reported abnormalities of prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and platelets count in some patients [22, 46, 47], these might not be consistent prognosticators [48]. Notwithstanding, decreased number of referrals with transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and minor stroke complaints, recent evidence express concerns toward increased LVO and major strokes in youth under 50 years old [11, 38, 49]. Healthcare system and general population involvement with COVID-19 must not miss such patient’s diagnosis. A retrospective study by Tang et al. in Wuhan showed that anticoagulant therapy with heparin (mainly low molecular weight heparin) for 7 days in patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) score ≥ 4 (40.0% vs. 64.2%, P = 0.029) or D-dimer > 6-fold of upper limit of normal (32.8% vs. 52.4%, P = 0.017) seems to be associated with better prognosis, but in other patients, no difference was found in 28-day mortality. The correlation between D-dimer level, prothrombin time (PT), and age were positive, but negative for platelet count and mortality [50]. In a retrospective multicentric cohort study on 1026 patients, Wang and colleagues imply on VTE anticoagulants prophylaxis in high-risk (with Padua prediction score 4 or more) COVID-19 patients. High-risk versus low-risk patients were older, had high risk of bleeding, were intensive care unit admitted, under mechanical ventilation, and died as a result of COVID-19 or COVID-19 complications such as VTE. Out of 40% high-risk patients, 11% developed VTE without prophylaxis. In addition, 11% of high VTE risk cases had concurrent high bleeding risk. This condition requires anticoagulant dose and duration adjustment and mechanical compressions such as elastic compression stocking or intermittent pneumatic compression [51]. According to harmful outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 severe respiratory dysfunction comorbidity with coagulopathy, suspicion to pulmonary embolism necessitates urgent objective diagnosis with suitable (close to therapeutic doses) heparin administration [52]. Owing to significant high incidence of thromboembolic events in critically ill ICU patients, high-dose prophylaxis must be considered, especially in ill predisposed patients to thromboembolic events [41]. Although bleeding risk in anticoagulation therapies always remains as an unavoidable concern, as antithrombin and antifactor Xa, direct oral anticoagulants ameliorate PAR-1 and proinflammatory cytokine production, and benefits might significantly outweigh the risk [20]. Beyrouti and colleagues recommend early anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in therapeutic doses regarding intracranial bleeding risk consideration [32]. Lee et al. suggested novel oral anticoagulants instead of vitamin K antagonists in stroke patients with atrial fibrillation. Also, previous risk modifying therapies must not be discontinued. The most challenging patient management problems are necessity to regular blood tests to monitor international normalized ratios and significant future cerebrocardiovascular event risk increasing in discontinuation of antihypertensive, anticoagulant, and statin therapy [53]. Despite recommended anticoagulation regimens, some evidence notifies the increasing risk of adverse bleeding events including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), parenchymal hemorrhage, punctuate hemorrhage, and small to large size hemorrhage with or without herniation in patients receiving either prophylactic or therapeutic doses [54]. Whereas considering high D-dimer level, sepsis physiology, and consumptive coagulopathy as indicators of mortality, due to insufficient clinical experiences in COVID-19 associated coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) management, standard supportive care measures with thromboembolic prophylaxis should administer as similar as any other critically ill hospitalized patients [19]. Wang et al. did not highly recommend endovascular thrombectomy based on their experience in young patients with LVO and severe stroke thrombectomy, due to large clot burdens, clot fragility, and distal migrating during mechanical thrombectomy [11].

Conclusion and future prospects

Based on recent hypothesis which proposes the probable association of stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection, in addition their first place in global morbidity and mortality with annually 15 million deaths, much more attention must be paid to preventive and therapeutic management of such patients. By government’s attempts to control viral transmission by quarantine, restriction of general population mobility, and people fear of COVID-19 infection in hospital refers, lots of patients may develop mild-to-moderate strokes. Therefore, government agencies must pay more attention on warning people to take precautions, mail-order options from their health care providers, local pharmacy delivery services, especially for those with a history of stroke. According to the latest information about stroke development in some COVID-19 patients, we recommend rational anticoagulation therapy especially in those with severe disease and comorbidities besides taking adverse bleeding event risk into account.

References

Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF (2020) A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 395(10223):470–473

Organization, W.H., WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. 2020

Jin H et al (2020) Consensus for prevention and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for neurologists. Stroke Vasc. Neurol:svn-2020–sv000382

Dalan R, Bornstein SR, el-Armouche A, Rodionov RN, Markov A, Wielockx B, Beuschlein F, Boehm BO (2020) The ACE-2 in COVID-19: foe or friend? Horm Metab Res 52(5):257–263

Tian S, Hu N, Lou J, Chen K, Kang X, Xiang Z, Chen H, Wang D, Liu N, Liu D, Chen G, Zhang Y, Li D, Li J, Lian H, Niu S, Zhang L, Zhang J (2020) Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Inf Secur 80:401–406

Cao X (2020) COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 20(5):269–270

Mao, L., et al., Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. 2020

Yavarpour-Bali H, Ghasemi-Kasman M (2020) Update on neurological manifestations of COVID-19. Life Sci 257:118063

Montalvan V, Lee J, Bueso T, de Toledo J, Rivas K (2020) Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 194:105921

Mansoor, S.R. and Ghasemi-Kasman, M, Impact of disease-modifying drugs on severity of COVID-19 infection in multiple sclerosis patients. Journal of Medical Virology. n/a(n/a)

Wang A, Mandigo GK, Yim PD, Meyers PM, Lavine SD (2020) Stroke and mechanical thrombectomy in patients with COVID-19: technical observations and patient characteristics. J. Neurointerv. Surg 12(7):648–653

Helms J et al (2020) High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med:1–10

Aggarwal G, Lippi G, Michael Henry B (2020) Cerebrovascular disease is associated with an increased disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis of published literature. Int J Stroke 15(4):385–389

Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T (2020) The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 92(6):552–555

Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, Zou W, Zhan J, Wang S, Xie Z, Zhuang H, Wu B, Zhong H, Shao H, Fang W, Gao D, Pei F, Li X, He Z, Xu D, Shi X, Anderson VM, Leong ASY (2005) Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med 202(3):415–424

Qin, C., et al., Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2020

Mehta P et al (2020) COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 395(10229):1033

Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P (2020) Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol 127:104362

Connors JM, Levy JH (2020) COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Am. J. Hematol 135(23):2033–2040

Jose, R.J. and A. Manuel, COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 2020

Leslie-Mazwi T et al (2020) Preserving access: a review of stroke thrombectomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Neuroradiol 41:1136–1141

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395(10223):497–506

Machado, C. J.V. Gutierrez, Brainstem dysfunction in SARS-COV2 infection can be a potential cause of respiratory distress. 2020

Markus HS, Brainin M (2020) COVID-19 and stroke—a global World Stroke Organization perspective. Int J Stroke 15(4):361–364

Zeng J-H et al (2020) First case of COVID-19 complicated with fulminant myocarditis: a case report and insights. Infection:1

Juusela A, Nazir M, Gimovsky M (2020) Two cases of COVID-19 related cardiomyopathy in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol:100113

Inciardi, R.M., et al., Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA cardiology, 2020

Lippi G, Plebani M (2020) Laboratory abnormalities in patients with COVID-2019 infection. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med 58(7):1131–1134

Oudit G et al (2009) SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Investig 39(7):618–625

Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, Xia P, Cao W, Jiang W, Chen H, Ding X, Zhao H, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhao J, Sun X, Tian R, Wu W, Wu D, Ma J, Chen Y, Zhang D, Xie J, Yan X, Zhou X, Liu Z, Wang J, du B, Qin Y, Gao P, Qin X, Xu Y, Zhang W, Li T, Zhang F, Zhao Y, Li Y, Zhang S (2020) Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382(17):e38

Harzallah, I., A. Debliquis, B. Drénou, Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with Covid-19. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH, 2020

Beyrouti, R., et al., Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2020

Avula, A., et al., COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 2020

Hughes C et al (2020) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a presentation of COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med:7(5)

González-Pinto, T., et al., Emergency room neurology in times of COVID-19: malignant ischemic stroke and SARS-COV2 infection. European journal of neurology, 2020

Al Saiegh, F., et al., Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2020

Viguier, A., et al., Acute ischemic stroke complicating common carotid artery thrombosis during a severe COVID-19 infection. Journal of neuroradiology, 2020

Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, de Leacy RA, Shigematsu T, Ladner TR, Yaeger KA, Skliut M, Weinberger J, Dangayach NS, Bederson JB, Tuhrim S, Fifi JT (2020) Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med 382(20):e60

Yeboah, K., et al., Interventional stroke management in a COVID-19 patient. Neurology: Clinical Practice, 2020

Immovilli P et al (2020) Stroke in COVID-19 patients—a case series from Italy. Int J Stroke:1747493020938294

Klok F et al (2020) Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res

Belani P, Schefflein J, Kihira S, Rigney B, Delman BN, Mahmoudi K, Mocco J, Majidi S, Yeckley J, Aggarwal A, Lefton D, Doshi AH (2020) COVID-19 is an independent risk factor for acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol 41:1361–1364

Siegler J et al (2020) Falling stroke rates during COVID-19 pandemic at a Comprehensive Stroke Center: Cover title: Falling stroke rates during COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis:104953

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, Angus DC, Rubenfeld GD, Singer M, for the Sepsis Definitions Task Force (2016) Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315(8):775–787

Lyons PG, Micek ST, Hampton N, Kollef MH (2018) Sepsis-associated coagulopathy severity predicts hospital mortality. Crit Care Med 46(5):736–742

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18(4):844–847

Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM (2020) Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta

Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, Clark C, Iba T (2020) ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 18(5):1023–1026

Baracchini C et al (2020) Acute stroke management pathway during Coronavirus-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci:1–3

Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z (2020) Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 18(5):1094–1099

Wang T, Chen R, Liu C, Liang W, Guan W, Tang R, Tang C, Zhang N, Zhong N, Li S (2020) Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID-19. Lancet Haematol 7(5):e362–e363

Ciavarella A, Peyvandi F, Martinelli I (2020) Where do we stand with antithrombotic prophylaxis in patients with COVID-19? Thromb Res 191:29

Lee M, Chen C, Ovbiagele B (2020) Covert COVID-19 complications: continuing the use of evidence-based drugs to minimize potentially lethal indirect effects of the pandemic in stroke patients. J Neurol Sci 414:116883–116883

Dogra S, Jain R, Cao M, Bilaloglu S, Zagzag D, Hochman S, Lewis A, Melmed K, Hochman K, Horwitz L, Galetta S, Berger J (2020) Hemorrhagic stroke and anticoagulation in COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 29:104984

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This is a review article, no human or animals ethical approval required.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Naeimi, R., Ghasemi–Kasman, M. Update on cerebrovascular manifestations of COVID-19. Neurol Sci 41, 3423–3435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04837-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04837-0