Abstract

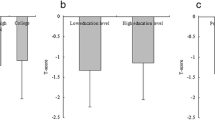

The objectives of this study are (1) to evaluate whether the prevalence of osteoporosis and peripheral fractures might be influenced by the educational level and (2) to develop a simple algorithm using a tree-based approach with education level and other easily collected clinical data that allow clinicians to classify women into varying levels of osteoporosis risk. A total number of 356 women with a mean age of 58.9 ± 7.7 years were included in this study. Patients were separated into four groups according to school educational level; group 1, no education (n = 98 patients); group 2, elementary level (n = 57 patients); group 3, secondary level (n = 138 patients) and group 4, university level (n = 66 patients). We observed dose–response linear relations between educational level and mean bone mineral density (BMD). The mean BMDs of education group 1 (10.39% (lumbar spine), 10.8% (trochanter), 16.8% (wrist), and 8.8% (femoral neck)) were lower compared with those of group IV (p < 0.05). Twelve percent of patient had peripheral fractures. The prevalence of peripheral fractures increased with lowered educational levels. Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant independent increase in the risk of peripheral fracture in patients with no formal education (odds ratio, 5.68; 95% , 1.16–27.64) after adjustment for age, BMI and spine BMD. Using the classification tree, four predictors were identified as the most important determinant for osteoporosis risk: the level of education, physical activity, age >62 years and BMI <30 kg/m2. This algorithm correctly classified 74% of the women with osteoporosis. Based on the area under the receiver–operator characteristic curves, the accuracy of the Classification and Regression Tree (CART) model was 0.79. Our findings suggested that a lower level of education was associated with significantly lower BMDs at the lumbar spine and the hip sites, and with higher prevalence of osteoporosis at these sites in a dose–response manner, even after controlling for the strong confounders. On the other hand, our CART algorithm based on four clinical variables may help to estimate the risk of osteoporosis in a health care system with limited resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Compston JE, Papapoulos SE, Blanchard F (1998) Report on osteoporosis in the European community: current status and recommendations for the future. Osteoporos Int 8:531–534

Gabriel SE, Tosteson AN, Leibson CL, Crowson CS et al (2002) Direct medical costs attributable to osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 3:323–330

Plimpton S, Root J (1994) Materials and strategies that work in low literacy health communication. Public Health Rep 09:86–92

Corral F, Cueva P, Yepez J et al (1996) Limited education as a risk factor in cervical cancer. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 30:322–329

La Vecchia C, Negri E, Pagano R et al (1987) Education, prevalence of disease, and frequency of health care utilisation. The 1983 Italian National Health Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 1:161–165

Pincus T, Callahan LF, Burkhauser RV (1987) Most chronic diseases are reported more frequently by individuals with fewer than 12 years of formal education in the age 18–64 United States population. J Chron Dis 40:865–74

Woo J, Leung SS, Ho SC et al (1999) Influence of educational level and marital status on dietary intake, obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors in a Hong Kong Chinese population. Eur J Clin Nutr 53:461–467

Varenna M, Binelli L, Zucchi F et al (1999) Prevalence of osteoporosis by educational level in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 9:236–241

Berarducci A, Lengacher C, Keller R (2002) The impact of osteoporosis continuing education on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes. J Contin Educ Nurs 33:210–216

Lauderdale DS, Salant T, Han KL et al (2001) Life-course predictors of ultrasonic heel measurement in a cross-sectional study of immigrant women from Southeast Asia. Am J Epidemiol 153:581–586

Lauderdale DS, Kuohung V, Chang SL et al (2003) Identifying older Chinese immigrants at high risk for osteoporosis. J Gen Intern Med 18:508–515

Shaw C (1993) An epidemiologic study of osteoporosis in Taiwan. Ann Epidemiol 3:64–71

Del Rio Barquero L, Baures MR, Segura JP (1992) Bone mineral density in two different socio-economic population groups. Bone Miner 18:159–68

Elliot JR, Gilchrist NL, Wells JE (1996) The effects of socioeconomic status on bone density in a male Caucasian population. Bone 18:371–373

Brecher LS, Pomerantz SC, Snyder BA et al (2002) Osteoporosis prevention project: a model multidisciplinary educational intervention. J Am Osteopath Assoc 102:327–335

MacDowell M, Guo L, Short A (2002) Preventive health services use, lifestyle health behavior risks, and self-reported health status of women in Ohio by ethnicity and completed education status. Womens Health Issues 12:96–102

Rolnick S, Kopher R, Jackson J et al (2001) What is the impact of osteoporosis education and bone mineral density testing for postmenopausal women in a managed care setting? Menopause 8:141–148

UNICEF. At a glance: Morocco. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/morocco_statistics.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2009

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML et al (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35:1381–1395

Fardellone P, Sebert JL, Bouraya M, Bonidan O, Leclercq G, Doutrellot C et al (1991) Evaluation of the calcium content of diet by frequential self-questionnaire. Rev Rhum Mal Osteo-Artic 58:99–103

Wang MC, Dixon LB (2006) Socioeconomic influences on bone health in postmenopausal women: findings from NHANES III, 1988–1994. Osteoporos Int 17:91–98

Ho S, Chen YM, Woo JL (2005) Educational Level and Osteoporosis Risk in Postmenopausal Chinese Women. Am J Epidemiol 161:680–690

Perez CR, Galan GF, Dilsen G (1993) Risk factors for hip fracture in Spanish and Turkish women. Bone 14(suppl 1):69–72

Wilson RT, Chase GA, Chrischilles EA, Wallace RB (2006) Hip fracture risk among community-dwelling elderly people in the United States: a prospective study of physical, cognitive, and socioeconomic indicators. Am J Public Health 96:1210–1218

Colon-Emeric CS, Biggs DP, Schenck AP, Lyles KW (2003) Risk factors for hip fracture in skilled nursing facilities: who should be evaluated? Osteoporos Int 14:484–489

Gur A, Sarac A, Nas A, Cevik R (2004) The relationship between educational level and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. BMC Fam Pract 5:18

Allali F, Maaroufi H, Aichaoui SE, Khazani H, Saoud B et al (2007) Influence of parity on bone mineral density and peripheral fracture risk in Moroccan postmenopausal women. Maturitas 57:392–398

Allali F, Aichaoui S, Saoud B, Maaroufi H, Abouqal R, Hajjaj-Hassouni N (2006) The impact of clothing style on bone mineral density among post menopausal women in Morocco: a case-control study. BMC Public Health 6:135

Khazzani H, Allali F, Ichchou L, Bennani L, Abouqal R, Hajjaj-Hassouni N (2007) Relation between the physical performance measures and the risk of peripheral fracture [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 66:527

Shea S, Stein AD, Basch CE et al (1991) Independent associations of educational attainment and ethnicity with behavioral risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol 134:567–582

Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, Abbott TA, Chen YT et al (2004) An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med 164:1113–1120

Dessein PH, Joffe BI, Veller MG, Stevens BA, Tobias M, Reddi K, Stanwix AE (2005) Traditional and nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors are associated with atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 32:435–442

Wolfe F, Pincus T, O'Dell J (2001) Evaluation and documentation of rheumatoid arthritis disease status in the clinic: which variables best predict change in therapy. J Rheumatol 28:1712–1717

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the University Mohammed V, Souissi, Rabat-Morocco.

Disclosures

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allali, F., Rostom, S., Bennani, L. et al. Educational level and osteoporosis risk in postmenopausal Moroccan women: a classification tree analysis. Clin Rheumatol 29, 1269–1275 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1535-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1535-y