Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to identify medications taken by patients before dental appointments and to simulate and characterize their interactions with medications often prescribed by dental surgeons.

Materials and methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study evaluated 320 medical records, 118 from the Emergency Service (ES) archives, and 202 from elective appointments at the Dental Clinic (DC) of a university in southern Brazil. Drug interactions were identified and classified according to severity using the Medscape® application into four grades: (1) Minor, (2) Monitor closely, (3) Serious, or (4) Contraindicated. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were carried out (α = 5%).

Results

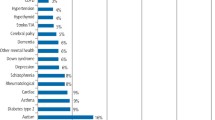

Preexisting systemic conditions were noted in 55.9% of the medical records from the ES and 64.35% from the DC. In the ES records, 47.45% contained information on continuous use medication for treatment of systemic conditions and 59.40% of DC records contained such information. A total of 359 potential interactions were found. Drug interactions with analgesics were most frequent, accounting for 50.41% of the sample.

Conclusions

The most prevalent drug interaction severity was grade 2: monitor or use with caution. Many patients take medications to treat systemic conditions and seek dental care, generating a significant possible source of drug interactions.

Clinical relevance

Prescribers must carefully analyze the patients’ medical histories and obtain accurate data regarding their use of medications to be able to assess the risk–benefit relationships of possible combinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

De-Paula KB, da Silveira LS, Fagundes GX, Ferreira MBC, Montagner F (2014) Patient automedication and professional prescription pattern in an urgency service in Brazil. Braz Oral Res 28:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2014.vol28.0041

Mohammadi Z (2009) Systemic, prophylactic and local applications of antimicrobials in endodontics: an update review. Int Dent J 59:175–186

GBD (2016) Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2017) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 16(390):1211–1259

Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER (2014) Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 13:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2013.827660

Kennedy C, Brewer L, Williams D (2016) Drug interactions. Medicine 1(44):422–426

Subramanian A, Adhimoolam M, Kannan S (2018) Study of drug-drug interactions among the hypertensive patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Perspect Clin Res 9:9–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_145_16

Weinstock RJ, Johnson MP (2016) Review of top 10 prescribed drugs and their interaction with dental treatment. Dent Clin North Am 60:421–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.005

Abramson JH (2011) WINPEPI updated: computer programs for epidemiologists, and their teaching potential. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 8:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-5573-8-1

Hersh EV, Moore PA (2008) Adverse drug interactions in dentistry. Periodontol 2000(46):109–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00224.x

Dao TT, LeResche L (2000) Gender differences in pain. J Orofac Pain. 14:169–84; discussion 184–195

Manski RJ, Hyde JS, Chen H, Moeller JF (2016) Differences among older adults in the types of dental services used in the United States. Inquiry 53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958016652523

Roblek T, Vaupotic T, Mrhar A, Lainscak M (2015) Drug-drug interaction software in clinical practice: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1786-7

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M et al (2013) 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 34:2159–2219

Yagiela JA (1999) Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: interactions associated with vasoconstrictors. Part V of a series. J Am Dent Assoc (1939) 130(5):701–709. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0280

Bavitz JB (2006) Dental management of patients with hypertension. Dent Clin North Am 50(4):547–vi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2006.06.003

Bangalore S, Kumar S, Messerli FH (2010) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated cough: deceptive information from the Physicians’ Desk Reference. Am J Med 123:1016–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.06.014

Joshi S, Bansal S (2013) A rare case report of amlodipine-induced gingival enlargement and review of its pathogenesis. Case Rep Dent 138248:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/138248

Marzolini C, Back D, Weber R, Furrer H, Cavassini M, Calmy A et al (2011) Ageing with HIV: medication use and risk for potential drug-drug interactions. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:2107–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkr248

Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC (2013) The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: polypharmacy. Drugs Aging 30:613–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0093-9

WHO | Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor (2017) https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1. Accessed 6 Dec 2018

Tiihonen J, Lehti M, Aaltonen M, Kivivuori J, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ et al (2015) Psychotropic drugs and homicide: a prospective cohort study from Finland. World Psychiatry 14:245–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20220

Gómez-Moreno G, Guardia J, Cutando A, Calvo-Guirado JL (2009) Pharmacological interactions of vasoconstrictors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 1(14):20–27

Moore PA (1999) Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: interactions associated with local anesthetics, sedatives and anxiolytics. Part IV of a series. J Am Dent Assoc (1939) 130(4):541–554. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0250

Moore PA, Gage TW, Hersh EV, Yagiela JA, Haas DA (1999) Adverse drug interactions in dental practice. Professional and educational implications. J Am Dent Assoc (1939) 130(1):47–54. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0028

Veehof L, Stewart R, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Jong BM (2000) The development of polypharmacy A longitudinal study. Fam Pract 17:261–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/17.3.261

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A (2007) Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol 63:187–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x

Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A, Malakouti SK, Bazargan M, Assari S (2016) Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 24(6):e010989. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010989

Aragoneses JM, Aragoneses J, Rodríguez C, Algar J, Suárez A (2021) Trends in antibiotic self-medication for dental pathologies among patients in the Dominican Republic: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Med 10(14):3092. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10143092

Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA (2007) Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther 29(Suppl):2477–2497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.003

Oksas RM (1978) Epidemiologic study of potential adverse drug reactions in dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 45:707–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(78)90145-7

Skaar DD, O’Connor H (2011) Potentially serious drug-drug interactions among community-dwelling older adult dental patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 112:153–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.03.048

Hersh EV, Moore PA (2015) Three serious drug interactions that every dentist should know about. Compend Contin Educ Dent (Jamesburg NJ 1995) 36(6):408–416

Funding

R.A. Arcanjo has received research grant from FAPERGS – Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Dentistry Research Committee (COMPESQ-ODO) (Protocol Number 35066) and by the Research Ethics Committee (Protocol CAAE 89135718.0.0000.5347).

Informed consent

The researchers were allowed to collect the retrospective data without having to ask participants for their individual consent. Researchers were careful to not share (or take notes) about the patient’s records. In addition to that, as the data will be analyzed and presented in groups (and not individually), this would prevent patients’ identification and secure their anonymity. Therefore, individual informed consents were not required.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, M.L.R., Nery, G.O., Torresan, T.T. et al. Frequency and characterization of potential drug interactions in dentistry—a cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Invest 26, 6829–6837 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-022-04644-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-022-04644-1