Abstract

In a vertically related duopoly with input price bargaining, this paper re-examines the downstream firms’ profitability under different market competition degrees. It is shown the rather counterintuitive result that downstream firms earn highest profits with semi-collusion, whose level depends on the upstream bargaining structures, the relative parties’ bargaining power, and the parameters measuring the degree of product differentiation in the downstream market. Concerning social welfare, the key result is that policymakers can tolerate some degree of collusion with decentralized bargaining structures; centralized structures advise for a more procompetitive policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Firms’ profitability in vertically related markets is a core topic in industrial economics and organization, and its relevance relies on the fact that (often) input suppliers (and among them, unions as labor suppliers) have relations based on negotiated price (wage) contracts with the producers of the final goods for consumers. However, the analysis of the interconnections between upstream input suppliers (unionized labor markets) and downstream product market competition is not fully explored. Therefore, the mechanisms through which imperfections in the upstream (labor) markets impact on the imperfections in the downstream product market are not yet indisputably clear.

Economic theory has stressed that several features must be taken into account when input price (wage) negotiations take place. One of the most relevant is the level of coordination between the parties during the bargaining process: either decentralized (uncoordinated) bargaining at each single upstream–downstream related unit or semi/full coordination among the parties during the negotiation process. The present paper precisely studies this aspect of negotiations. In particular, this work investigates the impact of upstream decentralization/coordination in input price bargaining and the competitive level of the downstream sector on downstream firms’ profitability. The rationale for the focus on those bargaining structures is as follows. If input suppliers are considered labor unions, upstream coordination represents the case of an industry-wide union, widely observed in the real world, that conducts negotiations separately in different companies. Despite the decentralization trend in (wage) negotiations that has taken place in the OECD countries, this bargaining configuration is still extremely relevant in the European Union. In particular, it represents a central labor market institution in continental Europe (see e.g. Buccella 2018).

The present paper focuses on the effects of different upstream coordination levels in negotiations on downstream firms profitability, stressing the relevance of different levels of downstream market competition/cooperation, measured both by a conjectural variation model, particularly by the conjectural derivative (CD) parameter and the degree of differentiation among goods. The main reason for choosing the CD in this work, despite its theoretical shortcomings (lack of direct link to observable primitives like the share of cross participation, see e.g. Symeonidis 2008, and Mukherjee 2010; involvement of pseudo-dynamics on intrinsically static models, see e.g., Varian 1992, p. 302, and Martin 2002, p. 45), is the key virtue of this analytical tool, i.e. its adaptability in encompassing the study of different market structures. In essence, the CD covers the full range of market competition levels, from Bertrand competition to joint profit maximization, using a unique, simple parameter. Moreover, the decisions of the firms in an industry with regard to tacit collusion (e.g. restriction of production or price cutting avoidance) may not be related to a directly observable variable (Ivaldi et al. 2007). The degree of product differentiation is also seen as another measure of the intensity of product market competition in industrial economics: the less the products are differentiated, the harsher the competition is among firms (Singh and Vives 1984; Shy 1995, pp. 138–140; Zanchettin 2006; Fanti and Meccheri 2014). Thus, the degree of product differentiation represents an additional element of analysis of the impact of market competition on the bargaining and, therefore, on firms’ profitability.

The key results of the paper are as follows. In sharp contrast to the conventional wisdom that the more the collusion is, the higher the profits for firms are, it is shown that more collusion can be detrimental for downstream firms’ profitability. The precise level of semi-collusion changes as the degree of product differentiation and the relative parties’ bargaining power vary. In this respect, the present paper generalizes the well-known non-merger paradox identified by Horn and Wolinsky (1988). More precisely, the following relations hold. First, for a given level of the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power, the more differentiated the products are, the higher the downstream firms’ collusion level is to maximize their profits, regardless of the upstream suppliers’ autonomous/coordinated bargaining structure. Second, while with decentralized input price (wage) bargaining, for a given degree of product differentiation, the higher the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power is, the lower the collusion level is of the downstream firms’ behavior to maximize profits, with bargaining coordination of the upstream input suppliers a U-shaped relation exists between the upstream firms’ bargaining power and the downstream sector’s competition level. In fact, downstream firms’ profits are at their maximum with high collusive levels, either when the upstream firms’ bargaining power is extremely low or extremely high, while profits are at their maximum for moderated levels of collusion when the upstream firms’ bargaining power is intermediate.

In so doing, this work attempts to contribute in shedding light on (and, therefore, provides a better understanding of) those links that are crucial both for the design of industrial policies and regulatory economics. In fact, the policy insight is that governments and antitrust authorities need a complete analysis of the related upstream sector(s) practices (or the labor market institution in place) and characteristics of the downstream one before designing a policy intervention to regulate product market competition in an industry.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature. Section 3 presents the model and the results. Section 4 briefly discusses some extensions of the basic model. Section 5 closes with an outline of the future research.

2 Related literature

The current paper relates to a wide strand of the economic literature on bargaining. Considering unions as the input suppliers, authors such as Davidson (1988), Horn and Wolinsky (1988), and Bárcena-Ruiz and Garzón (2002) have analyzed the outcomes of different wage bargaining structures in oligopolies. Davidson (1988) studies simultaneous negotiations in a duopoly with homogeneous final products. In an influential paper, Horn and Wolinsky (1988) broaden Davidson’s (1988) analysis to include the strategic effects emerging from product differentiation in a model in which input suppliers (unions) and downstream firms form bilateral monopolies. Those authors investigate the autonomous/coordinated negotiation structures endogenously arising in equilibrium and show that those structures crucially depend on the product substitutability/complementarity. Downstream firms’ incentives to merge are studied in presence of negotiations with a single input supplier/labor union. The analysis reveals that the sum of the duopoly profits is larger than the profits of a downstream monopoly if the products are substitutable. Therefore, the gains from having a downstream monopoly in the industry are lower than the losses due to a worsening of the bargaining position. The opposite result holds true if goods are complements. Likewise, Bárcena-Ruiz and Garzón (2002) build a model in which multiunit firms and unions as labor input suppliers endogenously select their wage-bargaining structures.

The contributions of Symeonidis (2008) and Mukherjee (2010) are also similar to the present work. Symeonidis (2008) constructs a model whereby the firm-specific labor unions (upstream input suppliers) negotiate wages (input prices) and shows that, in the case of uniform wage (input price) negotiations, the product market cooperation among downstream firms increases the consumer surplus and social welfare when goods are close substitutes and the unions (upstream suppliers) have significant relative bargaining power. On the other hand, if unions (upstream suppliers) have low bargaining power, social welfare is higher under Cournot competition in the downstream market. Conversely, in the case of two-part wage (tariff) negotiations, the profits and union (upstream) utility decrease as the intensity of the competition decreases, and the opposite holds for the consumer surplus and total welfare.

Mukherjee (2010) extensively analyses the impact of product market cooperation in a Cournot duopoly with homogeneous goods, in which the labor market is characterized by the presence of an industry-wide union that negotiates wages separately but simultaneously with the firms. The author shows that the union’s disagreement point in negotiations has a key impact on firms’ profitability. In fact, if the union has a sufficiently strong bargaining power and the outside option is the anticipated duopoly equilibrium output, an increase in the degree of product market cooperation leads firms to expand output and to adopt a lower negotiated wage; therefore, cooperation among firms (measured by the coefficient of cooperation; see e.g. Martin 2002) yields an increase in profits due to its direct effect of output expansion and its indirect effect through wage. On the other hand, if the union’s outside option is the monopoly output, the effect of market cooperation on output, negotiated wages, and profits is more complex. In fact, the monopoly output as a disagreement point allows the union to catch a larger share of the oligopoly rents and therefore to create a positive link between product market cooperation and wage. It follows that increasing product market cooperation tends to increase profits via its direct effect, but it tends to shrink profits because of the indirect effect through higher wages. As a consequence, the profits are maximized for intermediate levels of product market cooperation.

The paper also relates to the literature that studies the impact of different competition modes (Cournot vs. Bertrand) on profits in vertically related (mainly, unionized labor) markets (Correa-López and Naylor 2004; Correa-López 2007; Fanti and Meccheri 2012; Alipranti et al. 2014; Basak and Wang 2016; Basak 2017; Buccella and Fanti 2019; Wang and Li 2020).Footnote 1 In a decentralized wage (price) bargaining model with a monopolist upstream input supplier and two downstream final goods producers, Correa-López and Naylor (2004) show that, if the union (input supplier) is adequately wage (input price) oriented, Bertrand profits can be higher than Cournot ones, which is in contrast to the standard Singh and Vives’ (1984) finding.Footnote 2 Using a different framework, Alipranti et al. (2014) substantiate the result of Correa-López and Naylor (2004); in fact, those authors build a two-part tariff vertical pricing contract model in which the input suppliers and the downstream firms negotiate at the decentralized level a wholesale price and a fixed fee. By contrast, Correa-López (2007) shows that, in the case of input price-centralized negotiations, profits are not only higher under Cournot competition, but also the quantity contract is the downstream firms’ dominant strategy when the final products are substitutes. Indeed, if the input price is the outcome of centralized negotiations, the reversal of the Cournot–Bertrand profits ranking is usually precluded because the key element of the inter-union (upstream firms) competition in decentralized negotiations disappears.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, Fanti and Meccheri (2012) show that, while the literature has generally assumed linear costs, the assumption of convex costs may lead to the reversal of the Cournot–Bertrand profits ranking also in the presence of centralized negotiations.

Recently, Basak and Wang (2016), Basak (2017), Buccella and Fanti (2019), and Wang and Li (2020) reconsider the Cournot–Bertrand profit ranking in a vertically related upstream market for input (labor). Basak and Wang (2016) re-examine the endogenous selection of price (Bertrand) and quantity (Cournot) contracts in the vertically related upstream input market. Basak and Wang (2016) show that, in the case of full centralized bargaining with two-part tariff pricing, the price contract arises as the dominant strategy for downstream firms. Contrary to the findings obtained in similar vertical pricing models with decentralized negotiations, Basak (2017) shows that, in a centralized, industry-wide wage bargaining (input pricing contract), the downstream firms earn higher (lower) profits under Cournot competition than under Bertrand competition if the products are substitutes (complements), confirming the results of Correa-López (2007) and Fanti and Meccheri (2012). Making use of a conjectural variation model, Buccella and Fanti (2019) re-examine the subject of the firms’ profits ranking under different degrees of market competition in a unionized duopoly with industry-wide efficient bargaining. The authors show that, in the presence of separated wage negotiations, profits in Cournot-like competition are always larger than Bertrand-like ones; however, a uniform wage bargaining can lead to the appearance of profit-ranking reversal. On the other hand, Wang and Li (2020) study the effect of downstream competition/cooperation in the presence of decentralized bargaining between two downstream firms and an upstream monopolist over a two-part tariff input price. Those authors find that the upstream monopolist’s profits (resp. the downstream firms) and the competition intensity in the downstream product market have a U-shaped (resp. inverted U-shaped) relation, independent of the competition modes; moreover, if the intensity of competition is sufficiently high (low), the downstream firms earn higher profits under Bertrand (Cournot) competition.

3 The model and the results

Let us consider a duopoly industry in which firms 1 and 2 operate. Each firm produces differentiated goods using only labor (or a single input), \(l\), as a factor of production with a constant returns-to-scale technology. For simplicity, let us assume that each worker (unit of input) produces one unit of the goods, i.e. \(l = q\) so that employment and production are equivalent. The linear (inverse) demand schedules for goods are

where \(q_{i}\) and \(q_{j}\) are the two firms’ production levels, and \(c \in [0,1]\) defines the degree of product differentiation. When \(c = 0\), the goods are independent, and when \(c \to 1\), the goods tend to be substitutes. To describe different degrees of market competition, the model assumes that firms decide their production levels according to a CD model (Dowrick 1989; De Fraja 1993; Buccella 2011, 2014, 2015). Defining \(\lambda_{i} \in ( - 1,1)\) as \(\lambda_{i} = {{dq_{j} (q_{i} )} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{dq_{j} (q_{i} )} {dq_{i} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {dq_{i} }}\), it follows that, when \(\lambda_{i} = 0\), the model collapses in the Cournot model; values of \(\lambda_{i}\) above zero indicate that firms adopt a more collusive behavior, whereas values of \(\lambda_{i}\) below zero denote that the industry is more competitive. As is common in the literature (see e.g. Martin 2002, p. 46), it is assumed that all firms have identical, symmetric conjectures, so that \(\lambda_{i} = \lambda_{j} = \lambda\). Consequently, the firm’s profits are

In the next section, the analysis considers the Right-to-Manage (RTM) framework. Under RTM, firms and unions (upstream suppliers) bargain over the wage level (input price) in the first stage. Then, once the wage has been negotiated, the firms choose the output levels in stage two (e.g. Nickell and Andrews 1983). As usual, the model is solved by backward induction. Therefore, in the presence of RTM negotiations, in stage 2, from first-order conditions (FOCs) of (2), the equilibrium output in terms of input prices (wages) is

Thus, downstream firms’ profits can be expressed as

3.1 Upstream decentralized bargaining

Let us first consider decentralized input price (wage) negotiations as in Correa-López and Naylor (2004) and Alipranti et al. (2014). Input price (wage) negotiations take place simultaneously and autonomously in the two bargaining units. Under decentralized negotiations, the upstream suppliers’ profit function (union utility) takes the following form:

As is common in the literature, it is assumed that the input suppliers have symmetric bargaining power across units. Moreover, it is assumed that the upstream suppliers (firm-specific union) are neutrally oriented in their preferences over input price (wages) and output (employment) (or, an alternative interpretation is that it is risk neutral). The positive utility of the upstream supplier (firm or union) derives from the fact that the input price (bargained wage) is above the marginal cost (or reservation wage), \(w_{0}\), set, without loss of generality, equal to zero. The following generalized Nash Product models the bargaining solution

where the parameter \(\alpha \in (0,1)\) is the upstream suppliers’ relative bargaining power. In the case of decentralized negotiations, it is reasonable to assume that, when negotiations break down, the disagreement point of both bargaining parties equals zero. Given the Nash product in (6), it can be derived that the negotiated input prices (wages) in equilibrium are

with the following comparative statics: \(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \alpha } > 0\),\(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial c} < 0\) and \(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } > 0\). The intuition behind the first comparative statics is straightforward: an increase in the upstream suppliers’ (unions’) bargaining power allows them to negotiate higher prices (wages). The rationale for the second comparative statics is that, with substitute goods, the duopoly rents tend to shrink, and the upstream supplier (union) captures a lower share of those rents. Finally, the third comparative statics can be explained as follows. The equilibrium prices (wages) rise as the intensity of the downstream market competition diminishes (i.e., the value of the CD parameter increases): for the given prices, a less competitive market shrinks the industry’s total output. Two opposite effects are at work. On the one hand, the output contraction declines the firms’ input (labor) demand, which curbs upstream suppliers’ (unions’) prices (wage claims). On the other hand, reduced competition raises profits and duopoly rents; as a consequence, upstream suppliers (unions) can ask for higher prices (wages). The latter effect dominates the former, and thus upstream suppliers (unions) demand higher prices (wages).

Moreover, further analytical inspection reveals that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{\alpha \to 1} \,\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } > 0\) and \(\frac{{\partial^{2} w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda \partial \alpha } > 0\) for \(\alpha \in (0,1)\): the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power always has a complementary effect on (reinforces) the impact of the competition degree (the CD) parameter on negotiated prices (wages).

Substitution of (7) into (3) leads to the equilibrium output

with \(\frac{{\partial q_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\) and \(\frac{{\partial q_{i}^{*} }}{\partial c}\frac{ > }{ < }0\) if \(\lambda \frac{ < }{ > }\lambda^{\rm T} (\alpha ,c)\) in the relevant parameter space.Footnote 4 The rationale for the latter result is as follows. An increase in product differentiation shrinks output because firms can increase prices and, consequently, rents. However, if the market presents more the characteristic of Bertrand-like competition, firms can find beneficial output expansion in the presence of substitute goods to capture larger market shares in a wide range of upstream supplier bargaining strength (see Buccella 2015).

After substitutions of the equilibrium output and input prices in (7) and (8) into (6), the following expression for the downstream firms’ profits is obtained

An analytical inspection reveals that, in the significant range of the parameters, the following comparative static applies \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial c} < 0\): the market interactions tend to lower production levels if the goods are more differentiated, firms can charge higher prices, and therefore can earn larger profits. Differentiation of (9) with respect to \(\lambda\) yields

An analytical inspection of (10) reveals the following result.Footnote 5

Result 1. In a duopoly with CD and decentralized input price (wage) bargaining under RTM: 1) for a given level of the upstream supplier (union) bargaining power, the higher is the degree of substitutability, the less collusive is the downstream firms’ behavior that makes maximal profits; 2) for a given level of product differentiation, the higher the upstream firms bargaining power is, the lower is the downstream firms’ collusive level that makes maximal profits.

Proof:

See the Appendix.

The economic intuition behind Result 1 can be explained as follows. Consider the first part (1) of Result 1. The analysis of the second cross-partial (mixed) derivatives of the profit function shows the substitutability/complementarity of the two parameters measuring the degree of market competition, \(\lambda\) and \(c\). Analytical inspection reveals that lower product differentiation has a substitute effect on (reduces) profitability with respect to the conjectural parameter.

With a similar reasoning, consider now part (2) of Result 1. The analysis reveals that, when the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power increases, it has a substitute effect on (reduces) downstream firms’ profitability. In fact, the upstream suppliers charge high input prices (wages, in case of unions), thus increasing the downstream firms’ total costs and reducing output. However, the downstream firms’ collusion on output decreases when the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power rises: a further output reduction does not sufficiently push upward the downstream firms’ final prices and, therefore, the impact of the increase in total costs due to higher input prices overcomes the overall effect of output reduction on revenues. As a consequence, to increase their profitability, downstream firms behave in a (relatively) more competitive fashion.

3.2 Upstream coordinated bargaining

Let us now consider the case of the upstream suppliers’ coordinated bargaining (i.e. a form of semi-centralized bargaining) as Mukherjee (2010) and Basak (2017) in a similar fashion do. This can be alternatively interpreted as a monopoly upstream firm (an industry-wide union) negotiating with downstream firms. The cases of separate input prices (wages) are analyzed. The coordinated upstream suppliers (industry-wide union) negotiate(s) simultaneously though disjointedly with each downstream firm the input price (wage) to catch the idea that the coordinated upstream suppliers (industry-wide union) can have an incentive to behave opportunistically during the bargaining process (see McAfee and Schwartz 1994; Milliou and Petrakis 2007). In other words, the coordinated upstream suppliers (industry-wide union) cannot commit to each downstream firm that it will not negotiate more favorable conditions to enhance the competitive position of the rival. Under separate negotiations, the (coordinated) upstream suppliers profit function (union utility) takes the following form:

and, as in the previous subsection, it is assumed that the coordinated upstream suppliers (union) are (is) neutrally oriented in the preferences over input prices (wages) and output (employment) (or, assumption of risk neutrality). The marginal cost (or reservation wage), \(w_{0}\), is equal to zero as before. The following generalized Nash Product now models the bargaining solution

where \(D_{j}^{{}}\) is the coordinated upstream input suppliers’ (industry-wide union’s) outside option. On the other hand, each downstream firm’s outside option is zero. As is known (e.g. Horn and Wolinsky 1988), the bargaining parties’ outside option can be diversely specified. In contrast to Basak (2017) and as in Mukherjee (2010), the paper considers that, in the case of a breakdown in the negotiations at the bargaining unit \(i\), firm \(j\) can produce the anticipated duopoly equilibrium output, \(q_{j}^{ * D}\), at the equilibrium wage, \(w_{j}^{ * D}\), where \(q_{j}^{ * D} = \frac{{2(1 - w_{j}^{*D} ) - c[(1 - w_{i}^{*D} - \lambda (1 - w_{j}^{*D} )]}}{{4(1 + c\lambda ) - (1 - \lambda^{2} )c^{2} }}\). That is, the disagreement utility is \(D_{j}^{{}} = w_{j}^{ * } q_{j}^{ * } = w_{j}^{{}} q_{j}^{{}}\).

In the presence of separate input price (wage) negotiations, given (11), maximization w.r.t. \(w_{i}^{{}}\) of the Nash Product in (12) with the above definition of \(D_{j}^{{}}\) leads in equilibrium to

Comparison of (7) with (13) reveals that coordinated bargained prices (wages) are higher than decentralized ones: in fact, via coordination, upstream firms (unions) internalize the effects of their competition. As in the case of decentralized bargaining, the comparative statics show that \(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \alpha } > 0\), \(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial c} < 0\) and \(\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } > 0\), with the same qualitatively explanations. However, further analytical investigation reveals that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{\alpha \to 1} \,\frac{{\partial w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } = 0\), and \(\frac{{\partial^{2} w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda \partial \alpha } > 0\) for \(\alpha \in (0,\frac{1}{2}]\), while \(\frac{{\partial^{2} w_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda \partial \alpha }\frac{ > }{ < }0\) for \(\alpha \in \left( {\frac{1}{2},1} \right)\).

As previously explained, a more collusive behavior of downstream firms allows the upstream firms to negotiate higher prices: the output reduction lessens the downstream firms’ input demand, decreasing the upstream suppliers’ prices; less intensive competition improves downstream profits and rents, allowing upstream suppliers to catch a larger share of them. The latter effect is still dominating: upstream suppliers demand higher prices. However, when the upstream negotiation strength is above \(\alpha = \frac{1}{2}\), an increase of the upstream firms’ bargaining power starts intensifying the former effect. In fact, by exerting an excessive upward pressure on prices, the downstream firms’ input demand further lowers, tending progressively to cancel out the rent-catching effect.

Substitution of (13) into (3) gives the equilibrium output,

with \(\frac{{\partial q_{i}^{*} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\). Further analytical inspection reveals that \(\frac{{\partial q_{i}^{*} }}{\partial c} < 0\) for \(\lambda \in ( \approx - .265,1)\), while \(\frac{{\partial q_{i}^{*} }}{\partial c}\frac{ > }{ < }0\) for \(\lambda \in ( - 1, - .265]\) if \(c\frac{ > }{ < }c^{\rm T} (\alpha )\) in the relevant parameter space. The rationale for this finding is that, if the market is not characterized by a high degree of competitiveness, an increase in product differentiation shrinks output because firms can further raise prices and, consequently, rents.

Nonetheless, if the market is characterized by more Bertrand-like competition, downstream firms can find beneficial output expansion in the presence of substitute goods to capture larger market shares in a wide range of the coordinated upstream suppliers (industry-wide union) bargaining strength (see Buccella 2015).

Further substitution of (13) and (14) into (4) gives the expression of the downstream firms’ profits

with \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial c} < 0\), whose economic rationale is as in the previous subsection.

From an in-depth analytical inspection, the next result follows.Footnote 6

Result 2. In a duopoly with CV and coordinated upstream suppliers (industry-wide union) and separated wage bargaining under RTM: 1) for a given level of the upstream firms’ bargaining power, the higher the degree of substitutability, the less collusive the downstream firms’ behavior that makes maximal profits; 2) for a given level of product differentiation, a U-shaped relation exists between the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power and the degree of competitiveness. The downstream firms’ profits are maximal in presence of high collusive behaviors either when the upstream firms’ bargaining power is low or high, while they are maximal for more moderated collusive behaviors if the upstream input supplier bargaining power is at intermediate levels.

Proof

See the Appendix.

The economic intuition behind part (1) of Result 2 is precisely as in part (1) of Result 1. On the other hand, consider now part (2) of Result 2. The analysis of the second cross-partial derivatives of the profit function reveals that, when the upstream supplier’s bargaining power is low, an increasing \(\alpha\) has a substitute effect on (reduces) downstream firms’ profitability. The upstream supplier charges high input prices (wages, in the case of a union), thus increasing the downstream firms’ total costs and reducing output.

On the other hand, when the upstream supplier’s bargaining power is adequately high, the additional increase of the input prices further reduces output, which in turn pushes the downstream firms’ final prices upward to a such a level that, combined with the firm’s collusive behavior, has complementarity on downstream firms’ profitability. The combined positive effects due to output restriction on downstream firms’ revenues overcome the negative effects of higher wages on their total costs.Footnote 7

3.3 Welfare considerations

The above results show that the bargaining structure/coordination activities in the upstream industry (unionized labor market) have in particular a deep impact on the competitive degree of the downstream industry, showing that downstream firms do not always have an interest in excessive collusive behaviors.

Let us now consider the impact of the bargaining structure on the overall social welfare. In oligopoly models, underproduction will take place. In the present context, collusive behaviors in the downstream market tend to restrict further output. The vertically related market structure adds a market failure, whose magnitude depends on the bargaining configuration. To conduct this analysis, we consider the social welfare function, \(SW\), given by the sum of the downstream and upstream firms’ profits and the consumer surplus, \(CS = \left( {\frac{{q_{1}^{2} + 2cq_{1}^{{}} q_{1}^{{}} + q_{2}^{2} }}{2}} \right)\), and whose expression can be simplified as

Substitution of (8) and (14) into (16) gives

where D and C stand for “decentralized” and “coordinated”, respectively. Differentiation leads to the following comparative statistics: \(\frac{{\partial CS_{{}}^{D} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\), \(\frac{{\partial CS_{{}}^{C} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\), \(\frac{{\partial SW_{{}}^{D} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\), and \(\frac{{\partial SW_{{}}^{C} }}{\partial \lambda } < 0\). That is, irrespective of the bargaining structure, downstream collusive behavior can improve their profitability; however, the harm imposed to consumers more than offset those gains.

Nonetheless, defining \(\Delta SW = SW^{D} - SW^{C}\), differentiation reveals that \(\frac{\partial \Delta SW}{{\partial \lambda }} > 0\): the lower the intensity of competition is, the larger is the social welfare differential under the two bargaining structures. This leads to the following conclusion: the government could tolerate some degree of collusion in the presence of a decentralized bargaining structure; the presence of centralized bargaining advises for more procompetitive market interventions.

Knowing that the parties’ relative bargaining power impacts on the collusive degree in the downstream market, a government wishing to achieve a precise degree of competitiveness may design regulations shifting the relative strength in negotiations in favor of one of them. Furthermore, given that also the degree of product differentiation affects collusion, the introduction of product standards that firms have to fulfill could be potentially used to shape competition in the downstream industry. Thus, when the government and the antitrust authorities want to design a policy intervention to shape the product market competitiveness, a close look at the downstream product market characteristics and the related upstream sectors practices or the labor market institution in place is needed.

4 Extensions

The qualitative results of the model have been tested under different specifications. First, the case in which the upstream suppliers coordinate negotiations and commit to a uniform input price rate has been investigated, retaining the assumption that the upstream input suppliers’ outside option is the anticipated duopoly output. Under this specification, the standard result that downstream profits are maximal under full collusion is re-established. Second, the outcome of the upstream bargaining coordination with separated negotiations but with different outside options has been investigated. If the outside option equals zero, then the qualitative results of the model are confirmed. However, if the outside option for the upstream input suppliers is represented by the equilibrium monopoly output, then the standard result that full collusion guarantees the highest profitability for downstream firms is re-established.

Third, we have tested the decentralized vs centralized bargaining structure under the efficient bargaining model (upstream firms are implicitly assumed to be unions). Irrespective of the bargaining structure, we have found that profits are always increasing in the relevant range of \(\lambda\), independent of the bargaining power of the parties and degree of product differentiation: the more the firms behave in a collusive way, the higher their profits are. As a consequence, the standard result that full collusion maximizes downstream firms’ profits holds.

Finally, given that in the literature there are alternative measures defining the intensity of competition among firms, we have also tested the model using the notion of competition intensity of rivalry, also known as coefficient of cooperation (see Martin 2002, pp. 52–55; Escrihuela-Villar 2015, 2016). Our analysis shows that, under the coefficient of cooperation, irrespective of the bargaining structure, the standard result of full collusion maximizing downstream firms’ profits holds.

To sum up, those extensions (whose analytical details are available upon request from the authors) reveal that the outcome of input price negotiations is sensitive to the characteristics and elements of the bargaining process as well as to the precise definition of market competition/cooperation.

5 Conclusion

Making use of a CD model in a vertically related duopoly market (alternatively interpreted as a unionized duopoly), this paper has investigated how coordination among the upstream input suppliers (unions) in the bargaining process affect the downstream market competition level and profitability. In sharp contrast to the standard expected result that more collusion leads to higher profits for firms, it is shown that more collusion can be detrimental for downstream firms’ profitability. In fact, collusive-like behaviors, but not full collusion, ensures downstream firms’ highest profits, depending on the degree of product differentiation and the relative parties’ bargaining power. In detail, for a given level of the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power, the more differentiated the products are, the higher the level of collusion among downstream firms that maximizes profits, irrespective of the negotiations’ structure. On the other hand, with decentralized, uncoordinated input price (wage) negotiations, for a given level of the product differentiation, the higher the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power, the less collusive the firms’ behavior is to maximize profits, and with upstream firms’ bargaining coordination, there is a U-shaped relation between the upstream firms’ bargaining power and the downstream sector’s competition level. In fact, downstream firms’ profits are maximized by a high level of collusion either when the upstream firms’ bargaining power is low or high, while profits are maximized for moderated collusive behaviors if the upstream firms’ bargaining power is at intermediate levels. As a consequence, when designing a policy intervention to regulate product market competition in an industry, government and antitrust authorities need a comprehensive analysis of the related upstream sectors practices (or the labor market institution in place).

The results of the model are based on several restrictions. In fact, the analysis is limited to precise analytical forms for the demand and cost functions. A further step would be to check the robustness of the current findings in an extended game framework in which network industries, different production technologies, managerial delegation, and capacity choices are considered.

Notes

Making use of an Hotelling model in a vertical market structure, Wang et al. (2019) also investigate the impact of intensity of rivalry in a downstream market, i.e. how competition affects the equilibrium locations of the downstream firms. The authors show that the presence of upstream firms lessen the spatial competition of downstream firms; moreover, minimum differentiation is not achieved because the equilibrium outcome and the equilibrium product differentiation is insufficient relative to socially optimum. Differently from the non-monotonic relationship in the horizontal market, the higher is the weight attached to intensity of rivalry, the higher social welfare is. Finally, under the two-part tariff contracts, the equilibrium product differentiation is independent of the parties’ bargaining power.

Later, introducing labor decreasing returns, Fanti and Meccheri (2011) show that the “Cournot-Bertrand reversal result” may also apply in the presence of “total wage bill-maximizing” unions; that is, even if unions attach equal weight to wages and employment, thus when the crucial assumption of an adequately wage (input price) orientation is relaxed.

This is clearly noted by Fanti and Meccheri (2012, 895): “it is easy to infer the crucial role for obtaining the reversal result played by wage competition between firm-specific unions”. In particular, they attribute the absence of the reversal under centralized bargaining to the “wage rigidity result” proposed by Dhillon and Petrakis (2002) who state that, in the presence of a central union (input supplier), the wage rate (input price) is the same under both Cournot and Bertrand competition.

The analytical expression of \(\lambda^{\rm T} (\alpha ,c)\) is algebraically complex and not elegant. Therefore, for economy of space, it is not reported. The interested reader can obtain its expression upon request from the authors.

Further analytical inspection of (10) reveals that, in the relevant parameter space, \(\frac{{\partial^{2} \pi_{i} }}{{\partial \lambda^{2} }} \le 0\), and thus, the second-order conditions (SOCs) are satisfied.

Moreover, in the parameter space of analysis, it holds that \(\frac{{\partial^{2} \pi_{i} }}{{\partial \lambda^{2} }} \le 0\), and therefore the SOCs are satisfied.

Another economic interpretation of Result 2 is provided in the light of the contribution of Aghadadashli et al. (2016). Those authors show that if retailers and a single supplier bargain over a linear input price via Nash bargaining while the retailer sets the output levels in the final goods market (as in the present framework), then the higher is the derived demand elasticity (that is, the elasticity of demand of the downstream firm’s input of production) in equilibrium, the larger is the profit share of the downstream firm.

References

Agadadashli H, Dertwinkel-Kalt M, Wey C (2016) The Nash bargaining solution in vertical relations with linear input prices. Econ Lett 145:291–294

Alipranti M, Milliou C, Petrakis E (2014) Price vs quantity competition in a vertically related market. Econ Lett 124(1):122–126

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2002) The organization of wage bargaining in divisionalized firms. Aust Econ Pap 41(3):305–319

Basak D (2017) Cournot vs bertrand under centralized bargaining. Econ Lett 154:124–127

Basak D, Wang LFS (2016) Endogenous choice of price or quantity contract and the implications of two-part-tariff in a vertical structure. Econ Lett 138:53–56

Buccella D (2011) Corrigendum to “the strategic choice of union-oligopoly bargaining agenda” [Int. J. Ind. Organ. 17 (1999) 1029–1040]. Int J Ind Organ 29(6):690–693

Buccella D (2014) Product market competition with differentiated goods and social welfare in the presence of an industry-wide union. Port Econ J 13(2):131–140

Buccella D (2015) Unionized duopoly, market competition with differentiated products, and welfare. Economia e Politica Industriale 42(4):455–473

Buccella D (2018) The choice of the bargaining agenda in imperfectly competitive markets. Poltext, Warsaw

Buccella D, Fanti L (2019) Profits under centralized negotiations: the efficient bargaining case. BE J Theor Econ 19(2):20170176

Correa-López M (2007) Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly with upstream suppliers. J Econ Manag Strategy 16(2):469–505

Correa-López M, Naylor RA (2004) The Cournot-Bertrand profit differential: A reversal result in a differentiated duopoly with wage bargaining. Eur Econ Rev 48:681–696

Davidson C (1988) Multiunit bargaining in oligopolistic industries. J Lab Econ 6(3):397–422

De Fraja G (1993) Staggered vs. synchronised wage setting in oligopoly. Eur Econ Rev 37:1507–1522

Dhillon A, Petrakis E (2002) A generalised wage rigidity result. Int J Ind Organ 20:285–311

Dowrick S (1989) Union-oligopoly bargaining. Econ J 99:1123–1142

Escrihuela-Villar M (2015) A note on the equivalence of the conjectural variations solution and the coefficient of cooperation. BE J Theor Econ 15(2):473–480

Escrihuela-Villar M (2016) On merger profitability and the intensity of rivalry. BE J Econ Anal Policy 16(2):1203–1212

Fanti L, Meccheri N (2011) The Cournot–Bertrand profit differential in a differentiated duopoly with unions and labour decreasing returns. Econ Bull 31:233–244

Fanti L, Meccheri N (2012) Labour-decreasing returns, industry-wide union and Cournot–Bertrand profit ranking. A note. Econ Bull 32(1):894–904

Fanti L, Meccheri N (2014) Profits and competition under alternative technologies in a unionized duopoly with product differentiation. Res Econ 68(2):157–168

Horn H, Wolinsky A (1988) Bilateral monopolies and incentives for merger. RAND J Econ 19(3):408–419

Ivaldi M, Jullien B, Rey P, Seabright P, Tirole J (2007) The economics of tacit collusion: implications for merger control. In: Ghosal V, Stennek J (eds) The political economy of antitrust (contributions to economic analysis), vol 282. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 217–239

Martin S (2002) Advanced industrial economics, 2nd edn. Wiley, Oxford

McAfee RP, Schwartz M (1994) Opportunism in multilateral vertical contracting: nondiscrimination, exclusivity, and uniformity. Am Econ Rev 84(1):210–230

Milliou C, Petrakis E (2007) Upstream horizontal mergers, vertical contracts, and bargaining. Int J Ind Organ 25:963–987

Mukherjee A (2010) Product market cooperation, profits and welfare in the presence of labor union. J Ind Compet Trade 10:151–160

Nickell SJ, Andrews M (1983) Unions real wages and employment in Britain 1951–1979. Oxford Economic Papers 35, pp 183–206, Supplement

Shy O (1995) Industrial organization: theory and application. MIT Press, Cambridge

Singh N, Vives X (1984) Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. RAND J Econ 15:546–554

Symeonidis G (2008) Downstream competition, bargaining, and welfare. J Econ Manag Strategy 17(1):247–270

Varian H (1992) Microeconomic analysis, 3rd edn. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Wang X, Li J (2020) Downstream rivals’ competition, bargaining, and welfare. J Econ 131:61–75

Wang X, Li J, Wang LFS (2019) Vertical contract and competition intensity in Hotelling’s model. BE J Theor Econ 19(1):20170048

Zanchettin P (2006) Differentiated duopoly with asymmetric costs. J Econ Manag Strategy 15(4):999–1015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are extremely indebted to two anonymous referees, the participants at the VII Leonid Hurwicz Workshop on Mechanism Design Theory, Warsaw, 7–8 December 2018, seminar participants at the University of Siena, Italy, Düsseldorf Institute for Competition Economics (DICE), Germany, and University of Bamberg, Germany, and conference participants at the 14th Warsaw International Economic Meeting, 2–4 July 2019, for their useful comments and suggestions that have helped us to improve the quality and clarity of this paper. In particular, Domenico Buccella is thankful to Christian Wey (DICE) and Panagiotis Skartados for extremely constructive discussion. The usual disclaimers apply.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Result 1

The (exogenous) optimal collusion level solves the equation \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial \lambda } = 0\) in (10), and depends on

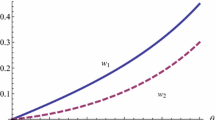

Solving explicitly (16) for \(\lambda\), three solutions are obtained, two conjunct imaginary and one real, graphically depicted in Fig.

1 (the analytical expression is available upon request).

Thus, \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial \lambda } \ge 0\) if \(\lambda^{ * } \ge 0\). Figure 1 shows that, in the relevant range \(\alpha \in {\text{(0,1) and }}c \in (0,1), \, \lambda^{*} (\alpha ,c) \ge 0\). Given that the SOCs are satisfied, an exogenous degree of market competitiveness exists such that profits are maximized. Moreover, partially differentiating (16) it is obtained that, for \(\alpha \in {\text{(0,1) and }}c \in (0,1)\)(see also Fig. 1),

Consider more in detail part (1) of Result 1. Holding constant the bargaining power of the upstream input supplier (union or manufacturer), \(\alpha = \mathop \alpha \limits^{\_}\), analytical inspection shows that \(\left. {\frac{d\lambda (c)}{{dc}}} \right|_{{\alpha = \mathop \alpha \limits^{\_} }} < 0\). From standard comparative statics, it holds that \({\text{sign }}\frac{d\lambda (c)}{{dc}} = {\text{sign }}\frac{{\partial^{2} \pi (\lambda (c),c)}}{\partial \lambda \partial c}\); that is, the sign of the derivative with respect to the conjectural parameter equals the sign the second cross-partial derivatives of the profit function with respect to the two parameters measuring the degree of market competition, \(\lambda\) and \(c\). The analysis of the second cross-partial (mixed) derivatives shows the substitutability/complementarity of the two parameters on firms’ profitability.

Given that \(\frac{d\lambda (c)}{{dc}} < 0\), it follows that lower product differentiation has a substitute effect on (reduces) profitability with respect to the conjectural parameter.

Similarly, consider in detail part (2) of Result 1. Keeping constant the degree of product differentiation, \(c = \mathop c\limits^{\_}\), an analytical inspection reveals that \(\left. {\frac{d\lambda (\alpha )}{{d\alpha }}} \right|_{{c = \mathop c\limits^{\_} }} < 0\). Given that \({\text{sign }}\frac{d\lambda (\alpha )}{{d\alpha }} = {\text{sign }}\frac{{\partial^{2} \pi (\lambda (\alpha ),\alpha )}}{\partial \lambda \partial \alpha }\), that is, the sign of the derivative with respect to the conjectural parameter equals that of the second cross-partial derivatives of the profit function with respect to the conjectural parameters and the bargaining power, \(\lambda\) and \(\alpha\), the analysis reveals that, when the upstream suppliers’ bargaining power increases, it has a substitute effect on (reduces) downstream firms’ profitability. \(\square\)

1.2 Proof of Result 2

Differentiation of (15) with respect to \(\lambda\) leads to.

The equation \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial \lambda } = 0\), which determines the (exogenous) optimal level of collusion, leads to four solutions, two conjuncts imaginary and two real. One of the real solutions gives only negative values of \(\lambda^{ * }\), outside the relevant range \(\lambda \in ( - 1,1)\). The other real solution generates a function \(\lambda^{ * } = \lambda^{ * } (\alpha ,c)\) which solves

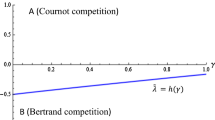

which again leads to three solutions, two conjuncts imaginary and one real which, for \(\alpha \in {\text{(0,1) and }}c \in (0,1)\), is in the relevant range \(\lambda \in ( - 1,1)\). Figure

2 shows that: 1) \(\lambda^{ * } > 0\), therefore \(\frac{{\partial \pi_{i} }}{\partial \lambda } \ge 0\): since the SOCs are satisfied, an exogenous, positive degree of market competitiveness exists such that profits are maximized; and 2) \(\left. {\frac{{d\lambda^{ * } (c)}}{dc}} \right|_{{\alpha = \mathop \alpha \limits^{\_} }} < 0\) and \(\left. {\frac{{d\lambda^{ * } (\alpha )}}{d\alpha }} \right|_{{c = \mathop c\limits^{\_} }} \frac{ < }{ > }0\) (a set of graphs that further exemplifies this point is available upon request).

The analytical details of part (1) of Result 2 are precisely as in part (1) of Result 1. Consider now in detail part (2) of Result 2. Keeping constant the degree of product differentiation, \(c = \mathop c\limits^{\_}\), an analytical inspection now shows that \(\left. {\frac{d\lambda (\alpha )}{{d\alpha }}} \right|_{{c = \mathop c\limits^{\_} }} \frac{ < }{ > }0\), with \({\text{sign }}\frac{d\lambda (\alpha )}{{d\alpha }} = {\text{sign }}\frac{{\partial^{2} \pi (\lambda (\alpha ),\alpha )}}{\partial \lambda \partial \alpha }\); that is, the sign of the derivative with respect to the conjectural parameter equals that of the second cross-partial derivatives of the profit function with respect to the conjectural parameters and the bargaining power, \(\lambda\) and \(\alpha\). Because \(\frac{d\lambda (\alpha )}{{d\alpha }}\frac{ < }{ > }0\), the analysis of the second cross-partial derivatives of the profit function reveals that the upstream supplier’s bargaining power can have either a substitute effect (reduces) (when \(\alpha\) is low) or a complement effect (increases) on downstream firms’ profitability.\(\square\)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buccella, D., Fanti, L. Downstream competition and profits under different input price bargaining structures. J Econ 136, 251–268 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-021-00772-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-021-00772-6