Abstract

Purpose

To compare patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) following surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or ankylosing spondylitis (AS) versus those without rheumatic diseases.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery. The primary outcome was change in the Neck Disability Index (NDI) at 1 year. Secondary endpoints included the European Myelopathy Score (EMS), quality of life (EuroQoL-5D [EQ-5D]), numeric rating scales (NRS) for headache, neck pain, and arm pain, and complications.

Results

Among 905 participants operated between 2012 and 2018, 35 had RA or AS. There were significant improvements in all PROMs at 1 year and no statistically significant difference between the cohorts in mean change in NDI (− 0.64, 95% CI − 8.1 to 6.8, P = .372), EQ-5D (0.10, 95% CI − 0.04 to 0.24, P = .168), NRS neck pain (− 0.8, 95% CI − 2.0 to 0.4, P = .210), NRS arm pain (− 0.6, 95% CI − 1.9 to 0.7, P = .351), and NRS headache (− 0.5, 95% CI − 1.7 to 0.8, P = .460).

Discussion and conclusion

Our study adds to the limited available evidence that surgical treatment cannot only arrest further progression of myelopathy but also improve functional status, neurological outcomes, and quality of life in patients with rheumatic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is the most common cause of spinal cord impairment and can cause neurological symptoms including gait disturbances, imbalance, loss of dexterity, poor coordination, pain and stiffness in the neck, pain and numbness in limbs, and autonomic alterations that may cause bowel, urinary, and sexual problems [1, 16]. DCM is typically caused by degenerative changes such as disc herniation, ligament hypertrophy or ossification, and osteophyte formation that may lead to spinal cord compression and dysfunction [16]. There are limited data on the epidemiology of DCM, and exact numbers of prevalence or incidence are lacking. In European studies, the prevalence of surgically treated DCM has been estimated between 1.6 and 4.7 per 100,000 inhabitants [2, 14]. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are prone to develop inflammatory and degenerative changes in the cervical spine that may, sometimes in combination with degenerative changes, result in myelopathy [7].

Although there is growing evidence that decompressive surgery can halt disease progression and is associated with meaningful improvement in function, pain, and quality of life [4, 5, 8], the data for patients with coexisting rheumatic conditions are sparse. Whether patients with RA or AS experience similar improvements in patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) following surgery remains unclear, and there is also a concern that they are more prone to complications [7]. While untreated DCM can lead to serious morbidity, management of patients with coexisting RA and AS remains controversial [10].

The aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness and safety of surgery for DCM in patients with RA or AS versus patients without rheumatic disease based on PROMs 1 year after surgery.

Methods

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics approved the study (2016/840), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was part of the first author’s master thesis at the Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

Study population

Patients were identified through the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine), a comprehensive nationwide registry for quality control and research. NORspine provides prospectively collected data on patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spinal disorders, and more than 80% of all cervical spine surgeries are included [8]. Patients were eligible if they had a diagnosis of DCM and underwent decompressive surgery between 2012 and 2018. The number of operated levels, surgical approach, and the use and type of instrumentation were performed at the surgeons’ discretion.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was change in the Neck Disability Index (NDI) at 1 year [11]. The NDI summary score ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less disability. The minimal clinically important change (MCIC) for NDI is approximately 7.5 points [15, 22].

Secondary outcome measures were changes in DCM severity assessed by the European Myelopathy Score (EMS) [9, 21], numeric rating scale (NRS) range 0 to 10 for headache, neck pain, and arm pain at 1 year [3], and quality of life assessed by EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D) [17]. For EQ-5D, an index value for health status is generated for each patient. Scores range from − 0.6 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect health. Patients’ perceived effect of surgery was assessed using Global Perceived Effect (GPE) scale, a seven-point scale [12]. Surgeons provided data on perioperative complications, and patients reported complications occurring within 3 months of hospital discharge.

Data collection

Baseline data were collected on admission for surgery where the patients completed a self-administered questionnaire. Using a standard registration form, surgeons recorded data on diagnosis, comorbidity, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, image findings, and surgical procedure. NORspine distributed self-administered questionnaires to the patients by mail 3 and 12 months after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 26 (IBM) and software R version 3.6.3. For statistical comparison tests, we defined the significance level as P ≤ 0.05. Changes in EMS, NDI, EQ-5D, and NRS were compared with paired sample T-test. Missing data were handled with mixed linear model analyses [20]. Because of the potential for type 1 and type 2 errors due to multiple comparisons and limited sample size, findings for analyses of secondary endpoints should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Among 905 patients included in this study, 35 (4%) were diagnosed with either RA (n = 25) or AS (n = 10). In total, 697 (77%) participants provided PROMs at 3 months and/or 1 year, with no statistically significant differences between the two cohorts (85.7% vs 76.7%, P = 0.21). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among patients with RA or AS, a posterior surgical approach was more common (62.9% vs 39.4%), and the patients had longer hospital stays (2.7 vs 1.6 days). ASA grade > 2 was more common in patients with RA or AS (37.1% vs 21.2%, P = 0.025).

Primary outcome

PROMs are presented in Table 2. For the total study population, there was a significant improvement in NDI (10.0 points, 95% CI 8.4 to 11.5, P < 0.001). Patients with RA or AS reported a higher NDI score before surgery (46.7 vs 34.5 points), but there was no statistically significant difference in mean change between the cohorts at 1 year in the complete case analysis (− 0.64, 95% CI − 8.1 to 6.8, P = 0.867). Patients with RA or AS experienced a significantly larger improvement in the mixed model analysis (difference in mean change − 8.8 points, 95% CI − 13.8 to − 3.7, P < 0.001). The change in NDI exceeded the MCIC of 7.5 points for both cohorts.

Secondary outcomes

There were significant improvements in all PROMs at 1 year for both cohorts. Complete case analyses showed no statistically significant difference between the cohorts in mean change in EQ-5D (0.10, 95% CI − 0.04 to 0.24, P = 0.168), neck pain NRS (− 0.8, 95% CI − 2.0 to 0.4, P = 0.210), arm pain NRS (− 0.6, 95% CI − 1.9 to 0.7, P = 0.351), and headache NRS (− 0.5, 95% CI − 1.7 to 0.8, P = 0.460). In the mixed model analysis, patients with RA or AS experienced statistically significant larger improvement in EQ-5D compared to those without rheumatic disease (mean difference − 0.28, 95% CI − 0.43 to − 0.14, P < 0.001). Patients with RA or AS had lower EMS scores at both baseline and at 1 year compared to patients without rheumatic disease. Improvement in EMS was larger in patients with RA or AS compared to those without. The change in EQ-5D for the total study population represents a moderate clinical change with an effect size of 0.51.

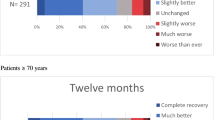

Patients’ perceived benefit of surgery assessed by the GPE is presented in Fig. 1. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the proportion of patients reporting “complete recovery” or feeling “much better” (25.1% vs 31.4%, P = 0.395).

Details of surgical treatment and complications are presented in Table 3. Patients with RA or AS were more likely to experience complications and adverse events within 3 months (42.9% vs 26.9%). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in perioperative complications.

Discussion

Although patients with RA or AS had more complications, they experienced improvements in their conditions after surgery for DCM that were similar to those of the patients without rheumatic disease. Our study adds to the limited available evidence that surgical treatment cannot only arrest further progression of myelopathy but also improve functional status, neurological outcomes, and quality of life in patients with rheumatic disease [10].

Patients with RA or AS reported higher disability and more severe myelopathy before surgery. Possible explanations include delay in diagnosis, disability due to the rheumatic disease itself, differences in disease progression and pathology, additional comorbidity, and a higher threshold for surgery in patients with RA or AS. In our study, the proportion of patients with symptoms exceeding 1 year was similar for both cohorts. A posterior surgical approach and instrumented fusion were more common in patients with RA or AS, suggestive of more pronounced DCM and multilevel involvement. A recent trial showed similar outcomes following anterior and posterior surgical approaches, but with higher complication rates for the former mainly due to more postoperative dysphagia and dysphonia [6]. There have been concerns regarding safety profile of surgery in patients with RA or AS due to medical treatments which may affect surgical outcomes and increase the risk of complications [7]. In our study, patients with RA or AS had an increased risk of complications after surgery, and this should be clearly communicated to patients prior to surgery. Life-threatening complications and early reoperations were fortunately rare.

Timely diagnosis of rheumatic disease and adequate medical treatment are likely to reduce the risk of developing DCM requiring surgery; however, the cases that need surgery are becoming more complex [10]. While conservative therapy can alleviate pain, surgery might be necessary to prevent serious morbidity [10, 13, 19]. As residual symptoms are common following surgery, early MRI and prompt referral to a spine specialist should be a priority in patients with clinical manifestations suggestive of myelopathy.

Limitations

Lack of verification of RA and AS diagnoses according to validated disease criteria by a rheumatologist is an important limitation. The two cohorts of patients were unequal relative to the number of participants, and as perhaps expected were not balanced for all baseline and treatment factors. Furthermore, the pathophysiology of DCM in patients with rheumatic disease is likely to differ from those without. Loss to follow-up is a concern. However, a previous study from NORspine showed no difference in outcomes between responders and non-responders [18]. NORspine only includes patients that actually undergo surgery, and unfortunately, we do not have any information about patients ineligible for surgical treatment due to, for example, frailty, comorbidity, and lack of motivation to undergo surgery. Patient characteristics, indications, and surgical strategies may vary between institutions and countries, and results from our study might differ from other countries and clinical settings. Another limitation is that patients in the cohort with rheumatic disease are carefully selected for surgery and might not be representative of the total population of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy and RA or AS. Moreover, the relatively low number of patients with RA or AS is also a limitation and may impact the generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

Patients with RA or AS experienced similar improvement following surgery for DCM compared to patients without rheumatic disease at the expense of more complications. Surgical treatment cannot only arrest further progression of DCM in patients with RA or AS, but also improve functional status, neurological outcomes, and quality of life.

Data availability

No additional data available.

References

Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Akbar MA, Witiw CD, Nassiri F, Furlan JC, Curt A, Wilson JR, Fehlings MG (2020) Degenerative cervical myelopathy - update and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol 16:108–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0303-0

Boogaarts HD, Bartels RH (2015) Prevalence of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J 24(Suppl 2):139–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-2781-x

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Kerns RD, Ader DN, Brandenburg N, Burke LB, Cella D, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Dionne R, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Katz NP, Kehlet H, Kramer LD, Manning DC, McCormick C, McDermott MP, McQuay HJ, Patel S, Porter L, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Revicki DA, Rothman M, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Stauffer JW, von Stein T, White RE, Witter J, Zavisic S (2008) Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 9:105–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005

Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Kopjar B, Yoon ST, Arnold PM, Massicotte EM, Vaccaro AR, Brodke DS, Shaffrey CI, Smith JS, Woodard EJ, Banco RJ, Chapman JR, Janssen ME, Bono CM, Sasso RC, Dekutoski MB, Gokaslan ZL (2013) Efficacy and safety of surgical decompression in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: results of the AOSpine North America prospective multi-center study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95:1651–1658. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.L.00589

Fehlings MG, Ibrahim A, Tetreault L, Albanese V, Alvarado M, Arnold P, Barbagallo G, Bartels R, Bolger C, Defino H, Kale S, Massicotte E, Moraes O, Scerrati M, Tan G, Tanaka M, Toyone T, Yukawa Y, Zhou Q, Zileli M, Kopjar B (2015) A global perspective on the outcomes of surgical decompression in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: results from the prospective multicenter AOSpine international study on 479 patients. Spine 40:1322–1328. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000000988

Ghogawala Z, Terrin N, Dunbar MR, Breeze JL, Freund KM, Kanter AS, Mummaneni PV, Bisson EF, Barker FG II, Schwartz JS, Harrop JS, Magge SN, Heary RF, Fehlings MG, Albert TJ, Arnold PM, Riew KD, Steinmetz MP, Wang MC, Whitmore RG, Heller JG, Benzel EC (2021) Effect of ventral vs dorsal spinal surgery on patient-reported physical functioning in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 325:942–951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1233

Gillick JL, Wainwright J, Das K (2015) Rheumatoid arthritis and the cervical spine: a review on the role of surgery. Int J Rheumatol 2015:252456. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/252456

Gulati S, Vangen-Lonne V, Nygaard OP, Gulati AM, Hammer TA, Johansen TO, Peul WC, Salvesen OO, Solberg TK (2021) Surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy: a nationwide registry-based observational study with patient-reported outcomes. Neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyab259

Herdmann JLM, Krzan M, Dvorak J, Bock WJ (1994) The European Myelopathy Score. Cerebellar infarct midline tumors minimally invasive endoscopic neurosurgery (MIEN) Advances in Neurosurgery 22

Janssen I, Nouri A, Tessitore E, Meyer B (2020) Cervical myelopathy in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis-a case series of 9 patients and a review of the literature. J Clin Med 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030811

Johansen JB, Andelic N, Bakke E, Holter EB, Mengshoel AM, Røe C (2013) Measurement properties of the norwegian version of the neck disability index in chronic neck pain. Spine 38:851–856. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827fc3e9

Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, Maher CG, de Vet HC, Hancock MJ (2010) Global Perceived effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 63:760-766.e761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009

Kothe R, Wiesner L, Rüther W (2002) Rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine. Current concepts for diagnosis and therapy. Orthopade 31:1114–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-002-0399-5

Kristiansen JA, Balteskard L, Slettebø H, Nygaard ØP, Lied B, Kolstad F, Solberg TK (2016) The use of surgery for cervical degenerative disease in Norway in the period 2008–2014: a population-based study of 6511 procedures. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 158:969–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-016-2760-1

MacDermid JC, Walton DM, Avery S, Blanchard A, Etruw E, McAlpine C, Goldsmith CH (2009) Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 39:400–417. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2930

Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG (2015) Degenerative cervical myelopathy: epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Spine 40:E675-693. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000913

Solberg TK, Olsen JA, Ingebrigtsen T, Hofoss D, Nygaard OP (2005) Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D can provide cost-utility data in the field of low-back surgery. Eur Spine J 14:1000–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-0898-2

Solberg TK, Sorlie A, Sjaavik K, Nygaard OP, Ingebrigtsen T (2011) Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine? Acta Orthop 82:56–63. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453674.2010.548024

Stein BE, Hassanzadeh H, Jain A, Lemma MA, Cohen DB, Kebaish KM (2014) Changing trends in cervical spine fusions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Spine 39:1178–1182. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000000376

Twisk J, de Boer M, de Vente W, Heymans M (2013) Multiple imputation of missing values was not necessary before performing a longitudinal mixed-model analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 66:1022–1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.017

Vitzthum HE, Dalitz K (2007) Analysis of five specific scores for cervical spondylogenic myelopathy. Eur Spine 16:2096–2103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0512-x

Young BA, Walker MJ, Strunce JB, Boyles RE, Whitman JM, Childs JD (2009) Responsiveness of the Neck Disability Index in patients with mechanical neck disorders. Spine J 9:802–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2009.06.002

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine). The registry receives funding from the University of Northern Norway and Norwegian health authorities. We are greatly indebted to all patients and spine surgeons who participate in NORspine registration.

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. STH, ØOS, and SG took part in the study design, statistical analyses, interpretation of results, and writing. ØPN and TKS were involved in collection of the data and writing of the manuscript. AMG, TOJ, ET, and VVL were involved in the interpretation of results and writing.

Author’s information

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics approved the study (2016/840), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

The author provides consent for all written material, tables, and figures to be published in the above journal.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Neurosurgery general

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holmberg, S.T., Gulati, A.M., Johansen, T.O. et al. Surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide registry-based study with patient-reported outcomes. Acta Neurochir 164, 3165–3171 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05382-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05382-9