Abstract

We define a map from tilings of surfaces with marked points to strand diagrams, generalising Scott’s construction for the case of triangulations of polygons. We thus obtain a map from tilings of surfaces to permutations of the marked points on boundary components, the Scott map. In the disk case (polygon tilings) we prove that the fibres of the Scott map are the flip equivalence classes. The result allows us to consider the size of the image as a generalisation of a classical combinatorial problem. We hence determine the size in low ranks.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In a groundbreaking paper [30] Scott proves that the homogeneous coordinate ring of a Grassmannian has a cluster algebra structure. In the process Scott gives a construction for Postnikov diagrams [26] starting from triangular tilings of polygons. Given a triangulation T, one decorates each triangle with ‘strands’

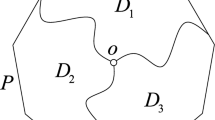

The resultant strand diagram \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) varies depending on the tiling, but induces a permutation \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\) on the polygon vertex set that is the same permutation in each case. This construction is amenable to generalisation in a number of ways. For example, starting with the notion of triangulation for an arbitrary marked surface S [11, 12] (the polygon case extended to include handles, multiple boundary components, and interior vertices) there is a simplicial complex A(S) of tilings [13,14,15] of which the triangulations are the top dimensional simplices. Lower simplices/tilings are obtained by deleting edges from a triangulation. There is a strand diagram \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) in each case (we define it below, see Fig. 1a, b for the heuristic). Thus each marked surface induces a subset \({\varvec{\sigma }}(A(S))\) of the set of permutations of its boundary vertices (see Figs. 2, 6 for examples).

This construction gives rise to a number of questions. The one we address here is, what are the fibres of this Scott map \({\varvec{\sigma }}\)? To give an intrinsic characterisation is a difficult problem in general. Here we give the answer in the polygon case, i.e. generalising \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\), with fibre the set of all triangulations of the polygon, to the full A-complex of the polygon.

The answer is in terms of another crucial geometrical device used in the theory of cluster mutations [12] and widely elsewhere (see e.g. [1, 11, 14, 17] and cf. [9])—flip equivalence (or the Whitehead move):

Our main Theorem, Theorem 2.1, can now be stated informally as in the title.

We shall conclude this introduction with some further remarks about related work. Then from Sects. 2–6 we turn to the precise definitions, formal statement and proof of Theorem 2.1.

In Sect. 7 we report on combinatorial aspects of the problem—specifically the size of the image of the map \({\varvec{\sigma }}\) in the polygon cases. The number of triangulations of polygons is given by the Catalan numbers. Taking the set \(A_r\) of all tilings of the r-gon, we have the little Schröder numbers (see e.g. [31, Ch.6]) The image-side problem is open. We use solutions to Schröder’s problem and related problems posed by Cayley (as in [25, 28]), and our Theorem to compute the sequence in low rank r, and in Sect. 7.4 prove a key Lemma towards the general problem. To give a flavour of the set \({\varvec{\sigma }}(A_r) \subset \Sigma _r\), the set of vertex permutations:

Finally in Sect. 8 we give some elementary applications of Theorem 2.1 to Postnikov’s alternating strand diagrams and the closely related reduced plabic graphs [26]. In particular we consider a direct map \({\mathsf {G}}\) from tilings to plabic graphs generalising [27, §2]. (A heuristic for this ‘stellar-replacement’ map is given by the examples and then Fig. 1c.)

The geometry and topology of the plane, and of two-manifolds, continues to reward study from several perspectives. Recent motivations include modelling of anyons for Topological Quantum Computation [18], fusion categories [1], cluster categories [4, 8], Teichmüller spaces [11, 15], frieze patterns [6], diagram algebras [16, 22, 29], classical problems in combinatorics [20, 28] and combinatorics of symmetric groups and permutations [29]. In Baur et al. [4] used Scott’s map [30] to produce strand diagrams for triangulated surfaces, again with the same permutation, in each case. This raises the intriguing question of which permutations are accessible in this way, and the role of the geometry in such constructions. Strictly speaking, the precise identification of permutations is dependent, in this setup, on a labelling convention. It is the numbers of permutations and the fibres over them (as we investigate here) that are, therefore, the main invariants accessible in the present formalism.

2 Definitions and results

Given any manifold X we write \(\partial X\) for the boundary and (X) for \(X{\setminus }\partial X\). For a subset \(D \subset X\) we write \(\overline{D}\) for its closure [23].

A marked surface is an oriented 2-manifold S; and a finite subset M. Set \(M_\partial = M \cap \partial S\). An arc in marked surface (S, M) is a curve \(\alpha \) in S such that \((\alpha )\) is an embedding of the open interval in \((S){\setminus } M\); \(\partial \alpha \subseteq M\); and if \(\alpha \) cuts out a simple disk D from S then \(|M \cap \overline{D}|>2\).

Two arcs \(\alpha ,\beta \) in (S, M) are compatible if there exist representatives \(\alpha '\) and \(\beta '\) in their isotopy classes such that \((\alpha ')\cap (\beta ')=\emptyset \).

A concrete tiling of (S, M) is a collection of pairwise compatible arcs that are in fact pairwise non-intersecting. A tiling T is a boundary-fixing ambient isotopy class of concrete tilings—which we may specify by a concrete representative, with arc set E(T) (it will be clear that this makes sense on classes). A tile of tiling T is a connected component of \(S{\setminus }\cup _{\alpha \in E(T)} \alpha \). We write F(T) for the set of tiles. (Note that if S is not homeomorphic to a disk then a tile need not be homeomorphic to a disk. For example a tile could be the whole of S in the case of Fig. 3.)

Fixing (S, M), it is a theorem that there are finite maximal sets of compatible arcs. Set \(\kappa (S,M) = 6g+3b+2p+|M|-6\), where g is the genus, b the number of connected components of \(\partial S\), and \(p=|M\cap (S)|\). Suppose \(\kappa (S,M) \ge 1\) and every boundary component intersects M. Then T maximal has \(|E(T)| = \kappa (S,M)\), and every tile is a simple disk bounded by three arcs. Evidently given a tiling T then the removal of an arc yields another tiling. In this sense the set of tilings of (S, M) forms a simplicial complex, denoted A(S, M).

We say two tilings are related by ‘flip’ if they differ only by the position of a diagonal triangulating a quadrilateral. The transitive closure of this relation is called \(flip\) equivalence. We write \([ T ]_{\Delta }\) for the equivalence class of the tiling T; and  for the set of classes of A(S, M).

for the set of classes of A(S, M).

2.1 The Scott map

Let L be a connected component of the boundary of an oriented 2-manifold, and P a finite subset labeled \(p_1, p_2,\dots , p_{|P|}\) in the clockwise order (a traveller along P in the clockwise direction keeps the manifold on her right). Then an \(umbral\) set \(P^{\pm }\) is a further subset of points \(p_i^-\) and \(p_i^+\) (\(i \in 1,2,\dots ,|P|\)) such that the clockwise order of all these points is \(\dots ,p_i, p_i^+ , p_{i+1}^- , p_{i+1},\dots \). That is, the interval \((p_i^- , p_i^+ ) \subset L\) contains only \(p_i\).

Given (S, M), let \(M^{\pm }\) denote a fixed collection of umbral sets over all boundary components. A \(Jordan\) diagram d on (S, M) is a finite number of closed oriented curves in S together with a collection of \(n=|M_\partial |\) oriented curves in S such that each curve passes from some \(p_i^+\) to some \(p_j^-\) in \(M^{\pm }\); and the collection of endpoints is \(M^{\pm }\). Intersections of curves are allowed, but must be transversal. Write \({{\varvec{\tau }}}(d)\) for the permutation of \(M_\partial \) this induces. That is, if \(p_i^+\) goes to \(p_j^-\) in d then \({{\varvec{\tau }}}(d)(i)=j\). Diagram d is considered up to boundary-fixing isotopy. Let \({\text {Pu}}(S,M)\) denote the set of Jordan diagrams.

Next we define a map \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!:A(S,M) \rightarrow {\text {Pu}}(S,M)\). Consider a tiling T in A(S, M). By construction each boundary L of a tile t is made up of segments of arcs, terminating at a set of points P. Hence we can associate \(P^{\pm }\) to P as above. To arc segment s passing from \(p_i\) to \(p_{i+1}\) say, we associate a strand segment \(\alpha _s\) in t passing from \(p_{i+1}^+\) to \(p_i^-\), such that the part of the tile on the s side of strand segment \(\alpha _s\) is a topological disk. Finally strand segment crossings are transversal and minimal in number. See tile t in Fig. 4 for example.

It will be clear that if two tiles meet at an arc segment then the umbral point constructions from each tile can be chosen to agree: as in Fig. 4. Applying the \(\alpha _s\) construction to every segment s of every tile t in T, we thus obtain a collection \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) of strand segments in S forming strands whose collection of terminal points are at the umbral points of \(\partial S\); so that \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\in {\text {Pu}}(S,M)\). Altogether, writing \(\Sigma _M\) for the set of permutations of set M, we have \({\varvec{\sigma }}: A(S,M) \rightarrow \Sigma _{M_\partial }\) defined by

We call this the Scott map. It agrees with Scott’s construction [30] in the case of triangulations of simple polygons.

We remark that the intermediate map \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) is injective, as we will show later (Theorem 8.4). The map \({\varvec{\sigma }}\) however is clearly not injective, as the image of any triangulation of a polygon is the permutation induced by \(i\mapsto i+2\).

The focus of this article is the case where (S, M) is a polygon P with n vertices. We write \(A_n\) for A(S, M) in this case,  for

for  , and \({\text {Pu}}_n\) for \({\text {Pu}}(S,M)\). Our main result can now be stated:

, and \({\text {Pu}}_n\) for \({\text {Pu}}(S,M)\). Our main result can now be stated:

Theorem 2.1

Let \(T_1, T_2\) \(\in A_n\) be tilings of an n-gon P. Then \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\) if and only if \([ T_1 ]_{\Delta } = [ T_2 ]_{\Delta }\).

Sections 3, 4, 5 and 6 are concerned with the proof of this result.

We will see in Lemma 3.5 that \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(A_n)\) lies in the subset of \({\text {Pu}}_n\) of alternating strand diagrams [26, §14]. Theorem 2.1 is thus related to Postnikov’s result [26, Corollary 14.2] that the permutations arising from two alternating strand diagrams are the same if and only if the strand diagrams can be obtained from each other through a sequence of certain kinds of ‘moves’. Consider the effect of a flip on the associated strands:

Comparing with Figure 14.2 of [26], the diagram shows that the flip corresponds to a certain combination of two types of Postnikov’s three moves (see Fig. 19). Thus, [26, Corollary 14.2] may be used for the “if” part of Theorem 2.1.

Remark 2.2

Theorem 2.1 does not hold as stated for arbitrary surfaces. For example, if T is a tiling of an annulus (S, M), then the Dehn twist of T induces the same permutation as T, regardless of the tile sizes. Similarly, if we consider tilings of punctured discs, the Scott map is invariant under certain rotations about the puncture.

2.2 Notation for tilings of polygons

We note here simplifying features of the polygon case that are useful in proofs.

Geometrically we may consider a tile as a subset of polygon P considered as a subset of \({\mathbb {R}}^2\). This facilitates the following definition.

Definition 2.3

Let \(T \in A_n\). By \({\text {Tr}}(T) \subset {\mathbb {R}}^2\) we denote the union of all triangles in T. We call \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) \(triangulated-part\) equivalent if \({\text {Tr}}(T_1)={\text {Tr}}(T_2)\) and they agree on the complement of \({\text {Tr}}(T_1)\). See Fig. 5.

By Hatcher’s Corollary in [14], two tilings are flip equivalent if and only if they are triangulated-part equivalent. The following is immediate.

Lemma 2.4

Let \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) be tilings of an n-gon P. All tiles of size \(\ge 4\) agree in these tilings if and only if \([ T_1 ]_{\Delta } = [ T_2 ]_{\Delta }\).

Write \(\underline{n}=\{1,2,\dots , n\}\) for the vertex set of P, assigned to vertices as for example in Fig. 6. The ‘vertices’ of \(A_n\) as a simplicial complex are the \(n(n-3)/2\) diagonals. A diagonal between polygon vertices i, j is uniquely determined by the vertices. We write \([ i,j ]\) for such a diagonal. Here order is unimportant. A tiling in \(A_n\) can then be given as its set of diagonals. Example: The tiling from \(A_8\) in Fig. 1 is \(T = \{[ 2,8 ], [ 3,5 ], [ 5,8 ] \}\). An example of a top-dimensional simplex (triangulation) in \(A_8\) of which this T is a face is \(T \cup \{ [ 3,8 ], [ 6,8 ]\}\).

Equally usefully, focussing instead on tiles, we may represent a tiling \(T \in A_n\) as a subset of the power set \({\mathcal {P}}(\underline{n})\): for \(T \in {\mathcal {P}}(\underline{n})\) one includes the subsets that are the vertex sets of tiles in T.

Example 2.5

In tile notation the tiling from \(A_8\) in Fig. 1 becomes

In this representation, while \(A_3 = \{ \{ \{ 1,2,3 \} \} \}\), we have:

We present two proofs of Theorem 2.1: one by constructing an inverse—in Sect. 4 we show how to determine the flip equivalence class from the permutation; and one by direct geometrical arguments—see Sect. 6. We first establish machinery used by both.

3 Machinery for proof of Theorem 2.1

The open dual \(\gamma (T)\) of tiling T is the dual graph of T regarded as a plane-embedded graph (see e.g. [7]) excluding the exterior face (so restricted to vertex set T). See Fig. 7 for an example.

Lemma 3.1

Graph \(\gamma (T)\) is a tree.

Proof

Let e be a diagonal of T and P the underlying n-gon. Then \(P{\setminus }e\) has two components. Thus removing a single edge separates \(\gamma (T)\). \(\square \)

A proper tiling is a tiling with at least two tiles. An ear in a proper tiling T is a tile with one edge a diagonal. An r-ear is an r-gonal ear.

Corollary 3.2

Every proper tiling has at least 2 ears. \(\square \)

3.1 Elementary properties of strands

Consider a tiling T. Note that a tile t in T and an edge e of t determine a strand of the \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) construction—the strand leaving t through e. Now, when a strand s leaves a tile t through an edge e it passes to an adjacent tile \(t'\) (as in Fig. 7), or exits P and terminates. We associate a (possibly empty) branch \(\gamma _{t,e}\) of \(\gamma (T)\) to this strand at e: the subgraph accessible from the vertex of \(t'\) without touching t. Note that the continuation of the strand s leaves \(t'\) at some edge \(e'\) distinct from e, and that \(\gamma _{t',e'} \) is a subgraph of \( \gamma _{t,e}\).

Lemma 3.3

Consider the strand construction on a tiling. After leaving a tile a strand does not return.

Proof

Consider the strand as in the paragraph above. If the strand exits the polygon P at e we are done. Otherwise, since the sequence of graphs \(\gamma _{t^i,e^i}\) associated to the passage of the strand is a decreasing sequence of graphs, containing each other, it eventually leaves P and terminates in some tile of a vertex of \(\gamma _{t',e'}\) and so does not return to t. \(\square \)

An immediate consequence of Lemma 3.3 is the following:

Corollary 3.4

A strand of a tiling T can only use one strand segment of a given tile of T.

Lemma 3.5

Let \(T\in A_n\) be a tiling of an n-gon. Then the strands of \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) have the following properties [26, §14]: (i) Crossings are transversal and the strands crossing a given strand alternate in direction. (ii) If two strands cross twice, they form an oriented digon. (iii) No strand crosses itself.

Proof

The first two properties follow from the construction. That no strand crosses itself follows from Corollary 3.4. Note that the underlying polygon can be drawn convex, in which case strands are left-turning. The requirement that there are no unoriented digons follows from the fact that strands are left-turning in this sense. (Remark: our main construction is unaffected by non-convexity-preserving ambient isotopies, but the left-turning property is only preserved under convexity preserving maps.) \(\square \)

We write \(x \leadsto y\) for a strand starting at vertex x and ending at vertex y. Thus if \(x \leadsto y\) is a strand of tiling T and \(\sigma \) is \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\) then this strand determines \(\sigma (x)=y\).

If a list of vertices is ordered minimally clockwise around the polygon, we will often just say clockwise, for example (7, 1, 2) is ordered minimally clockwise. To emphasise that vertices \(x_1,x_2,x_3\) are ordered minimally clockwise, we will repeat the “smallest” element at the end: \( x_1<x_2<x_3<x_1. \)

Definition 3.6

Let q be a vertex of a polygon with strand diagram.

-

(1)

We say that a strand \(x\leadsto y\) covers q if we have \(x<q<y<x\) minimally clockwise.

-

(2)

We say that \(x\leadsto y\) covers strand \(x'\leadsto y'\) if \(x<x'<y'<y<x\) or \(x<y'<x'<y<x\).

3.2 Factorisation Lemma

Consider the two strands \(s_1,s_2\) passing through an edge e of a tile t. We say these strands are ‘antiparallel at e’; and consider the ‘parallel’ strand \(s_1\) and antistrand \(\overline{s_2}\) both moving into t from e. See Fig. 8 for examples.

Lemma 3.7

(‘Lensing Lemma’) (I) Let strand segments \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) be antiparallel at an edge e of a tile t in a polygon tiling T. Traversing the two segments in the direction from e into the tile t, they do one of the following: (a) if t is a triangle the segments cross in t and do not meet again; (b) if t is a quadrilateral the segments leave t antiparallel in the opposite edge; (c) if \(|t| >4\) they leave t in different edges and the strands do not cross thereafter.

(II) In any polygon tiling T, two strands cross at most twice. If two strands cross twice then (i) they pass through a common edge e; (ii) the crossings occur in triangles, on either side of e, with only quadrilaterals between.

Proof

(I) See the Fig. 8. Note that in cases (a) and (c) the strands pass out of t through different edges and hence into different subpolygons. Now use Lemma 3.3. (II) Every crossing has to occur in a tile. If two strands enter a tile across different edges, they have not crossed before entering into the tile (Lemma 3.1). The claim then follows from (I). \(\square \)

Lemma 3.8

Let T be a tiling of an n-gon and \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\). Then (a) \(\sigma \) has no fixed points and (b) there is no i with \(\sigma (i)=i+1\).

Proof

(a) Let i be a vertex of the polygon. If i is not simple, the claim follows from the left-turning property. If i is simple, the strand starting at i follows the edge \(e=[i-1,i]\) before leaving this tile at a vertex different from i. By Lemma 3.3, it never returns back to the tile. (b) Consider the tile with edge \(e=[i,i+1]\). The strand starting at i and the strand ending at \(i+1\) have segments in the same tile and hence differ by Corollary 3.4. \(\square \)

Lemma 3.9

(‘Factorisation Lemma’) Let P be a polygon and \(T_1,T_2\) two tilings of P. Assume that there exists a diagonal \(e=[i,j]\) in \(T_1\) and \(T_2\). Denote by \(P'\) the polygon on vertices \(\{i,i+1,\dots , j-1,j\}\). We have:

Proof

Consider Fig. 9. The only way a strand of \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_1)\) passes out of \(P'\) is through e, and there is exactly one such strand (and one passing in). This strand is non-returning by Lemma 3.3, so its endpoints are identifiable from \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)\) as the unique vertex pair k, l with \(\sigma (k) = l\) and with k in \(P'\) and l not. Apart from this and the corresponding ‘incoming’ pair with \(\sigma (k') = l'\), all other strand endpoint pairs of \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_1|_{P'})\) are as in \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_1)\) and hence agree with \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_2|_{P'})\) if \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\). Indeed, if \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\) then \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\) identifies the same two pairs k, l and \(k',l'\). At this point it is enough to show that the image of vertex k under \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_1|_{P'})\), which is either vertex i or j, is the same as for \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T_2|_{P'})\). But it is i in both cases since the strand passing out of \(P'\) through e is at i. \(\square \)

3.3 Properties of strands and tiles

We will say that a vertex in polygon P is simple in tiling T if it is not the endpoint of a diagonal. We will say that an edge \(e=[i,i+1]\) of P is a simple edge in T if both vertices are simple.

Lemma 3.10

A strand \(i+1 \leadsto i\) arises in \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\) if and only if the edge \([i,i+1]\) is simple.

Proof

If \([i,i+1]\) is simple in T, the claim follows by construction. If i is not simple, then the strand ending at i contains the strand segment of the diagonal [j, i] of T with \(j<i-1\) maximal clockwise and has starting point in \(\{j,j+1,\dots , i-2\}\). Similarly, if \(i+1\) is not simple, the strand starting at \(i+1\) contains the strand segment of the diagonal \([i+1,k]\) with \(k>i+2\) minimal anticlockwise. Its ending point is among \(\{i+3,\dots , k\}\). \(\square \)

In general a strand passes through a sequence of tiles. At each such tile it is parallel to one edge and passes through the two adjacent edges. Any remaining edges in the tile are called complementary to the strand. Each of these complementary edges defines a sub-tiling—the tiling of the part of P on the other side of the edge. We call this the complement to the corresponding edge. Note that the strand covers every vertex in this sub-tiling. See for example Fig. 10. We deduce:

Lemma 3.11

-

(I)

A strand \(i \leadsto i+2\) passes only through triangles.

-

(II)

A strand \(i \leadsto i+3\) passes through one quadrilateral (with empty complement) and otherwise triangles.

-

(III)

A strand \(i \leadsto i+4\) passes through one quadrilateral (with a complementary triangle) or two quadrilaterals or one pentagon (with empty complement), and otherwise triangles.

-

(IV)

A strand \(i \leadsto i+k\) passes through a tile sequence \(Q_i\) such that

$$\begin{aligned} k-2 \ge \sum _i \left( |Q_i| -3\right) \end{aligned}$$(the non-saturation of the bound corresponds to some tiles having non-empty complement).

Example 3.12

As an illustration for Lemma 3.11 consider Fig. 6. Both tilings have a strand \(6\leadsto 9\), illustrating the case \(k=3\).

In the tiling on the left, there is a strand \(13\leadsto 3\) passing through one quadrilateral with complementary triangle \(\{14,1,2\}\).

Lemma 3.13

Let \(T \in A_n\) and \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\). Then \(\sigma (i) = i+2\) if and only if there exists \(T' \in [ T ]_{\Delta }\) with a 3-ear at vertex \(i+1\).

Proof

If: \( T'\) has a strand direct from i to \(i+2\) in the given ear. Note that all other tilings in \([ T' ]_{\Delta }\) have only triangles incident at \(i+1\) (since a neighbourhood of \(i+1\) lies in the triangulated part). One sees from the construction that these tilings all have a strand from i to \(i+2\). See (a):

(Note that Postnikov’s result [26, Corollary 14.2] and the strand/flip construction in Sect. 2.1 also implies the “if” part. For self-containedness we will avoid assuming Postnikov’s result.)

Only if: If there is no such \(T'\) in \([ T ]_{\Delta }\) then among the tiles incident at \(i+1\) is one with order \(r>3\). The strand from i passes into P at the first tile incident at \(i+1\). If this is a triangle then the strand passes into the second tile incident at \(i+1\), and so on. Thus eventually the strand meets a tile of higher order—see (b) above. But then by Lemma 3.11 we have \(i \leadsto i+k\) with \(k>2\). \(\square \)

For given n let us write \(\tau \) for the basic cycle element in \(\Sigma _n\): \(\tau =(1,2,\ldots ,n)\). The following is implicit in [30], and is a corollary to Lemma 3.11.

Lemma 3.14

For \(T \in A_n\), \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T) = \tau ^2\) if and only if T is a triangulation.

Definition 3.15

A run is a subsequence of form \(i-1,i-2,\ldots ,i-r+1\) in a cycle of a permutation of \(\Sigma _n\). A maximal subsequence of this form is an r-run at i.

In Fig. 6, both permutations have a 3-run at 9.

Lemma 3.16

Let \(T\in A_n\), and \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\). We have

-

(i)

\(\sigma \) contains a cycle of length \(\ge r\), where \(r\ge 2\), with an r-run at j \(\Longleftrightarrow \) \([j-1,j-2]\), \([j-2,j-3], \dots , [j-r+2,j-r+1]\) is a maximal sequence of simple edges in T;

-

(ii)

Assume \(\sigma \) is as in (i) and \(r<n-1\). Then TFAE

(a) \([j-r,j]\in T\); (b) \(\{j-r,j-r+1,\dots , j\}\) is an \((r+1)\)-ear in T; (c) \(\sigma (j-r)=j\).

Note that the case \(r=2\) occurs if \(j-1\) is simple, while the edge \([j-1,j-2]\) is not simple—a triangular ear.

Proof

-

(i)

Follows from Lemma 3.10.

-

(ii)

Observe that the the assumptions in (ii) are consistent with (b). (a) \(\Longrightarrow \) (b) follows from the assumptions. (b) \(\Longrightarrow \) (c) follows from the construction.

To show (c) \(\Longrightarrow \) (a) first note that by the assumptions, j and \(j-r\) are not simple. Among the diagonals incident with j consider the diagonal \([j,q_1]\) maximal clockwise from j. Among the diagonals incident with \(j-r\) consider the diagonal \([q_2,j-r]\) maximal anticlockwise from \(j-r\).

If \(q_1=j-r\) (and hence \(q_2=j\)), we are done. So assume for contradiction that \(j<q_1\le q_2<j-r<j\). Both diagonals are edges of a common tile Q containing the simple edges \([j-1,j-2]\), \([j-2,j-3], \dots , [j-r+2,j-r+1]\). Consider the strand starting at \(j-r\). It leaves the tile Q at an edge at \(q_2\). By Corollary 3.4 it cannot return back into Q, and so its endpoint is different from j. \(\square \)

4 Inductive proof of Theorem

One proof strategy for the main theorem (Theorem 2.1) is as follows. We assume the theorem is true for orders \(m<n\) (the induction base is clear).

The ‘If’ part follows from the Factorisation Lemma (Lemma 3.9) and Lemma 3.14.

For the ‘Only if’ part proceed as follows. Consider \(T_1,T_2\) with \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1) = {\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\). Note that \(T_1\) has an ear, either triangular or bigger (Corollary 3.2). Pick such an ear E. Consider the cases (i) \(|E|=3\); (ii) \(|E|\ne 3\).

(i) If E is triangular in \(T_1\) then \(\sigma ={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)\) has \(i \leadsto i+2\) at the corresponding position. Thus so does \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)\), and hence there is a \(T_2'\) in \([ T_2 ]_{\Delta }\) also with this ear, by Lemma 3.13. Note that \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2')={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\) since \(T_2'\sim _{\triangle } T_2\).

Since \(T_1{\setminus }E\) and \(T_2'{\setminus }E\) are well defined we have \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1{\setminus }E) = {\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2'{\setminus }E)\) by the Factorisation Lemma (Lemma 3.9). That is, the Scott permutations \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)\) and \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2')\) of \(T_1\) and \(T_2'\) agree on the part excluding this triangle. But then \([ (T_1{\setminus } E) ]_{\Delta } = [ (T_2'{\setminus } E) ]_{\Delta } \) (i.e. the restricted tilings agree up to triangulation) by the inductive assumption. Adding the triangle back in we have \([ T_1 ]_{\Delta } = [ T_2' ]_{\Delta }\). But \([ T_2' ]_{\Delta } = [ T_2 ]_{\Delta }\) and we are done for this case.

(ii) If ear E is not triangular in \(T_1\) then \(T_2\) has an ear in the same position by Lemma 3.16. The argument is a direct simplification of that in (i), considering \(T_1 {\setminus }E\) and \(T_2 {\setminus } E\). \(\square \)

5 Geometric properties of tiles and strands

Definition 5.1

Fix n. Then an increasing subset \(Q=\{ q_1, q_2, \ldots ,q_r \}\) of \(\{ 1,2,\ldots ,n \}\) defines two partitions:

We denote the parts by \(I_i(Q):=[q_i,\dots , q_{i+1})\) and \(J_i(Q):=(q_i,\dots , q_{i+1}]\), for \(i=1,\dots , r\).

Such partitions arise from tilings: Let \(Q\in T \in A_n\). Then the vertices of Q partition the vertices of P in two ways. Consider the edge \(e=[q_i,q_{i+1}]\) of Q. In the subpolygon on the vertices \(q_i,q_{i}+1,\dots , q_{i+1}\), there are \(q_{i+1}-q_i\) strands of \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) starting at vertices in \(I_i(Q)\) and the same number of strands ending at the vertices in \(J_i(Q)\). Among them, \(q_{i+1}-q_i-1\) remain in the subpolygon.

For an example, see Fig. 11.

Using this notation, we get an alternative proof for Corollary 3.4 stating that a strand of a tiling can only use one strand segment of a given tile: Let Q be a tile of a tiling \(T\in A_n\) and let \(q_1,\dots , q_r\) be its vertices, \(r\ge 3\), \(q_1<q_2<\cdots< q_r<q_1\). Assume strand \(x\leadsto y\) involves a strand segment of Q, say parallel to the edge \([q_{i-1},q_i]\). By construction, this strand segment is oriented from \(q_i\) to \(q_{i-1}\), comes from the subpolygon on the vertices \(q_i, q_i+1,\dots , q_{i+1}\) and then passes into the subpolygon on the vertices \(q_{i-2},q_{i-2}+1,\dots , q_{i-1}\). We claim that the strand then necessarily starts in \(I_i(Q)\) and ends in \(J_{i-2}(Q)\), i.e. that \(x\ne q_{i+1}\) and \(y\ne q_{i-2}\). We show that it ends in \(J_{i-2}(Q)\): Consider the subpolygon on the vertices \(q_{i-2}, q_{i-2}+1,\dots , q_{i-1}\), bounded by the edge \([q_{i-1},q_i]\). From the orientation of strand segments in tiles, it is clear, that the strand then leaves this subpolygon near z where \(z\in \{q_{i-2}+1,\dots , q_{i-1}-1\}\) is the first vertex met when going from \(q_{i-2}\) towards \(q_{i-1}\) which has an edge \([z,q_{i-1}]\). Hence \(y\in J_{i-2}(Q)\). A similar argument shows \(x\in I_i(Q)\).

Remark 5.2

Let T be a tiling of P, with tile Q inducing partitions as above. There are two types of strands regarding these partitions. Let \(x\leadsto y\) be a strand starting in \(I_{i_1}(Q)\) and ending in \(J_{i_2}(Q)\) for some \(i_1,i_2\). Then we either have \(i_1=i_2\) or \(i_1=i_2+2\) (by the preceding argument or by Corollary 3.4). The case \(i_1=i_2+2\) is illustrated in Fig. 11 for Q a pentagon.

Definition 5.3

Let Q be a tile of a tiling T of an n-gon. If a strand \(x\leadsto y\) of T uses a strand segment of Q, we say that the strand \(x\leadsto y\) is a long strand for Q. If for the partitions induced by Q, \(x\in I_i(Q)\), then \(y\in J_{i-2}(Q)\) if \(x\leadsto y\) is a long strand for Q and \(y\in J_i(Q)\) otherwise, cf. Remark 5.2.

Lemma 5.4

Let Q be an r-tile of a tiling of P with vertices \(q_1<\cdots< q_r<q_1\) clockwise. Then every long strand \(x\leadsto y\) with respect to Q covers exactly \(r-2\) vertices of Q and there are exactly two vertices \(q_{i-1},q_i\) for every such strand with \(y\le q_{i-1}<q_i\le x<y\) (clockwise).

Proof

If s is a long strand for Q with \(x\leadsto y\), then there exists i such that \(x\in I_i(Q)=[q_i,\dots , q_{i+1})\) and \(y\in J_{i-2}(Q)=(q_{i-2},\dots , q_{i-1}]\) (reducing the index mod n), hence it covers \(q_{i+1},q_{i+2}, \dots , q_{i-2}\). For an illustration, see Fig. 11. \(\square \)

6 Geometric Proof of Theorem

We now use geometric properties of tilings to prove the “only if” part of Theorem 2.1. The maximum tile size of tiling T is denoted r(T). For two tilings \(T_1,T_2\) and \(r_i = r(T_i)\), the case \(r_1\ne r_2\) is covered in Corollary 6.3; and \(r:=r_1=r_2\) follows from Lemma 6.4. We first prove an auxiliary result.

Lemma 6.1

-

(a)

Consider a tiling T in \(A_n\) with a diagonal \(e=[s_1,s_2]\). For each vertex q with \(s_1< q< s_2<s_1\), there exists a strand \(s:y\leadsto z\) in \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) covering q, with \(s_1\le y<q<z\le s_2<s_1\).

-

(b)

Consider T, q, s as in (a) and a further tiling \(T'\) of P containing a tile Q such that \(\dim (Q \cap e)=1\) and \(q \in Q\). If \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T')\) contains a strand with \(y\leadsto z\) as in (a), it is a long strand for Q (as defined in Definition 5.3).

Proof

(a) Let \(e'=[n_1,n_2]\) be the shortest diagonal in T lying above q. Note, \(s_1\le n_1<q<n_2\le s_2<s_1\). Consider the strand segment in \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T)\) following \(e'\) from \(n_1\) to \(n_2\) (see figure below). This induces a strand s with \(y\leadsto z\), say. We claim \(n_1\le y<q\) and \(q<z\le n_2\). To see this let \([x,n_1]\) be in T with \(n_1\le x<n_2\), x maximal (\(x=n_1+1\) possibly). Then \(x\le q\) since \(e'\) is the shortest diagonal above q and so s has its starting point among \(\{n_1,n_1+1,\dots , x-1\}\). A similar argument proves the claim for y.

(b) Given (a), this follows immediately from Definition 5.3. \(\square \)

Lemma 6.2

Let \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\). If in \(T_1\) there exists an edge \(e=[s_1,s_2]\) and in \(T_2\) a tile Q of size \(\ge 4\) with \(\dim (Q\cap e)=1\), then either e is an edge of Q or e separates vertices of Q (\(s_1> q_x> s_2> q_y > s_1\) for some x, y) and \(|Q|=4\).

Proof

If e is not an edge of Q, we find vertices \(q_i\) and \(q_j\) of Q with \(s_1<q_i<s_2<q_j<s_1\). We can thus use Lemmas 5.4 and 6.1 for \(q_i\) and again for \(q_j\) to see that Q has \(r-2\) vertices on the left side of e and \(r-2\) vertices to the right of e, and that they all differ from \(s_1\) and from \(s_2\), where \(r=|Q|\). So \(r=2(r-2)\) and \(r=4\). \(\square \)

Corollary 6.3

Let \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) be two tilings of a polygon P with \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1) = {\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\). Then \(r_1 = r_2\).

Proof

Let \(r=r_2\). Assume that \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\). In case \(r_1=3\), the claim follows from Lemma 3.14: in this case, \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1)\) is induced by \(i\mapsto i+2\) and \(T_2\) has to be a triangulation, too. Assume for contradiction that \(r_1<r\). Since we can assume \(r_1>3\), we have \(r>4\). We consider a tile Q of size \(r>4\) in \(T_2\), with vertices \(q_1,\dots , q_r\). In \(T_1\), we choose a tile S with \(\dim (Q\cap S)> 1\). Then S has an edge e with \(\dim (Q\cap e)=1\) and so by Lemma 6.2, Q is a tile of \(T_1\), a contradiction to the maximal tile size in \(T_1\).

\(\square \)

Lemma 6.4

Let \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) be two tilings of a polygon P with \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1) = {\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2)\) and assume \(r_1=r_2=4\). Then \([ T_1 ]_{\Delta } = [ T_2 ]_{\Delta }\).

Proof

By Lemma 3.10 the positions of 4-ears in \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) agree, when \(r_1=r_2=4\). By the Factorisation Lemma (Lemma 3.9) we can remove (common) ears of size 4, to leave reduced tilings \(T_1'\) and \(T_2'\) of some \(P'\). These necessarily have ears, but by Lemma 3.11, (up to equivalence) 3-ears can be chosen to be in the same positions in each tiling. Now iterate. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 2.1

If the maximum tile sizes of \(T_1\) and of \(T_2\) differ, the claim follows from Corollary 6.3. So let \(r=r_1=r_2\) be the maximum tile size of \(T_1\) and of \(T_2\). If \(r=4\), Lemma 6.4 proves the claim. So assume that there are tiles of size \(r>4\) and consider such a tile Q in \(T_2\). By Lemma 6.2 there are no diagonals of \(T_1\) ‘intersecting’ Q, so in \(T_1\) we have a tile containing Q. Applying the same argument with the tilings reversed we see that \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) agree on parts tiled with tiles of size \(>4\).

By the Factorisation Lemma (Lemma 3.9), we can remove all (common) ears of size \(>4\). Among the remaining (common) tiles of size at least 5, we choose a tile Q and a non-boundary edge e of Q, such that to one side of e, all tiles in \(T_1\) and in \(T_2\) have size at most four. Let \(P'\) be the union of these tiles of size \(\le 4\). By the Factorisation Lemma we have \({\varvec{\sigma }}(T_1\mid _{P'})={\varvec{\sigma }}(T_2\mid _{P'})\) and by Lemma 6.4, \([ T_1\mid _{P'} ]_{\Delta } =[ T_2\mid _{P'} ]_{\Delta }\). We can remove \(P'\) and repeat the above until Q is a (common) ear - which can be removed, too. Iterating this proves the claim. \(\square \)

7 On the image of the Scott map treated combinatorially

To give an intrinsic characterization of the image in \(\Sigma _n\) of the Scott map \({\varvec{\sigma }}: A_n \rightarrow \Sigma _n\) for all n remains an interesting open problem. Note in particular that so far the map does not equip the image with a group structure (or indeed any algebraic structure). Here we report on one invariant which Theorem 2.1 gives us access to, namely the size of the image, which is given by .

As an initial illustration we observe that:

Proposition 7.1

The number of permutations arising from tiling an n-gon using one r-gon (\(r>3\)) and triangles otherwise is \(n\atopwithdelims ()r\).

Proof

By the main Theorem this is the same as enumerating the classes in  of this type. Since the details of the triangulated part are irrelevant, the class is determined by choosing the vertices of the r-gon. Hence choosing r from n. \(\square \)

of this type. Since the details of the triangulated part are irrelevant, the class is determined by choosing the vertices of the r-gon. Hence choosing r from n. \(\square \)

Example 7.2

In total, there are 26 permutations arising from the 45 tilings of the hexagon: one from the empty tiling; 6 from tilings with one pentagon and one triangle; 15 from tilings with one quadrilateral and two triangles; 3 from tilings using two quadrilaterals; and 1 from the triangulation case.

Figure 2 contains examples of these tilings and the associated permutations.

In order to go further we will need some notation.

7.1 Notation and known results

Recall that an integer partition \(\lambda =(\lambda _1,\lambda _2,\dots )\) has also the exponent notation:

where \(\alpha _i\) is the number of parts in \(\lambda \) equal to i. A \(\lambda \)-tiling is a tiling with, for each d, \(\alpha _d\) tiles that are \((d+2)\)-gonal.

Recall that \(A_n\) is the complex of tilings of the n-gon. Define \(a_n = |A_n| \). Write \(A_n(m)\) (with \(m \in \{0,1,2,\dots , n-3 \}\)) for the set (and \(a_n(m)\) the number) of tilings with m diagonals. Write \(A_n(\lambda )\) (with \(\lambda \) an integer partition of \(n-2\)) for the set of \(\lambda \)-tilings (thus with a m-gonal face for each row \(\lambda _i = m-2\)). Thus

where \(\lambda '\) denotes the conjugate partition to \(\lambda \) [21], so \(\lambda '_{1}\) is the number of parts.

Similarly recall  is the set of classes of tilings under triangulated-part/flip equivalence. Write

is the set of classes of tilings under triangulated-part/flip equivalence. Write  for the set \(A_n(m)\) under triangulated-part equivalence and

for the set \(A_n(m)\) under triangulated-part equivalence and  the set \(A_n(\lambda )\) under triangulated-part equivalence.

the set \(A_n(\lambda )\) under triangulated-part equivalence.

(7.3) The sequence \(a_n\) is the little Schröder numbers (see e.g. [31] and OEIS A001003). It is related to the Fuss–Euler combinatoric as follows. By [28] the number of tilings of the n-gon with m diagonals is

(\(a_n(m) = q_m(1,n) \) from [28]). Thus in addition to the usual generating function

we have

7.2 Explicit construction of \(A_n\)

Of greater use than an expression for the size of \(A_n\) is an explicit construction of all tilings. For this we shall consider a tiling in \(A_n\) to be as in the formal definition, i.e. to be the same as its set of arcs. This is the set of diagonals in the present polygon case, where we can represent an arc between vertices i, j unambiguously by \([ i,j ]\). In particular then we have an inclusion \(A_{n-1} \hookrightarrow A_n\). The copy of \(A_{n-1}\) in \(A_n\) is precisely the subset of tilings in which vertex n is simple and there is no diagonal \([ 1,n-1 ]\).

There is a disjoint image \(J(A_{n-1})\) of \(A_{n-1}\) in \(A_n\) given by \(J(T)=T \cup \{[ 1, n-1 ]\}\). The set \(A_{n-1} \sqcup J(A_{n-1})\) is the subset of \(A_n\) of elements in which n is simple. Consider in the complement the subset of tilings containing \([ n-2,n ]\). In this the vertex \(n-1\) is necessarily simple. Thus this subset is the analogue \(J_{n-1}(A_{n-1})\) of \(J(A_{n-1})\) constructed with \(n-1\) instead of n as the distinguished simple vertex. The practical difference is that (i) the image tilings have all occurences of \(n-1\) replaced by n; (ii) the ‘added’ diagonal is \([ n-2,n ]\).

There remain in \(A_n\) the tilings in which n is not simple but there is not a diagonal \([ n-2,n ]\). Consider those for which there is a diagonal \([ n-3, n ]\). In the presence of this diagonal any tiling ‘factorises’ into the parts in the two subpolygons on either side of this diagonal. One of these has vertices \(1,2,\ldots ,n-3\) and n, and so its tilings are an image of \(A_{n-2}\) where vertex \(n-2\) becomes vertex n. The other has vertices \(n-3,n-2,n-1,n\) and so has tilings from a shifted image of \(A_4\), but has n simple (since \([ n-3 , n ]\) is the first diagonal in the original tiling). Since n is simple, it is the part of that image coming from \(A_3 \sqcup J(A_3)\). We write \(2.K(A_3)\) for these two shifted copied of \(A_3\). We write \(2.K(A_3)\cdot A_{n-2}\) for the meld with tilings from \(A_{n-2}\) to construct the set of tilings of the original polygon.

There now remain in \(A_n\) the tilings in which n is not simple but there is not a diagonal \([ n-2,n ]\) or \([ n-3,n ]\). Consider those for which there is a diagonal \([ n-4, n ]\). In the presence of this diagonal any tiling ‘factorises’ into the parts in the two subpolygons on either side of this diagonal. We have the obvious generalisation of the preceeding construction in this case, written \(2.K(A_4)\cdot A_{n-3}\).

We may iterate this construction until all cases of diagonals from n are included. We have established the following.

Proposition 7.4

Consider the list defined recursively by \({\mathbf {A}}_3 = (\emptyset )\) and

where set operations on lists are considered as concatenation in the natural order; \(2.-\) denotes the doubling as above; K() denotes the relabeling of all vertices so that the argument describes a suitable subpolygon; and \(A\cdot B\) denotes the meld of tilings from subpolygons as above. Then this list is precisely a total order of \(A_n\).

Proof

Noting the argument preceding the Proposition, it remains to lift the construction from the set to the list. But this requires only the interpretation of union as concatenation. \(\square \)

7.3 Tables for \(A_n(\lambda )\)

The class sets  are harder to enumerate than \(A_n\). Practically, one approach is to list elements of \(A_n\) and organise by arrangement of their triangulated parts, which determines the class size. We first recall the numbers \(a_n(m)\) of tilings of an n-gon with m diagonals: see Table 1. The main diagonal enumerates the top dimensional simplices in \(A_n\). It counts triangulations and hence is the Catalan sequence \(C_n\). The entries in the next diagonal correspond to tilings with a single quadrilateral and triangles else.

are harder to enumerate than \(A_n\). Practically, one approach is to list elements of \(A_n\) and organise by arrangement of their triangulated parts, which determines the class size. We first recall the numbers \(a_n(m)\) of tilings of an n-gon with m diagonals: see Table 1. The main diagonal enumerates the top dimensional simplices in \(A_n\). It counts triangulations and hence is the Catalan sequence \(C_n\). The entries in the next diagonal correspond to tilings with a single quadrilateral and triangles else.

sizes up to \(n=10\)

sizes up to \(n=10\)We will give the number of elements of  for small n in Table 2. In order to verify this it will be convenient to refine Tables 1 and 2 by considering these numbers for fixed partitions \(\lambda \). Specifically we subdivide each case of m from the previous tables according to \(\lambda \), with the m-th composite entry written as a list of entries in the form \((\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \ldots ) \over a_n(\lambda )\) ranging over all \(\lambda \) with \(|\lambda | =m\). Thus for example \((32) \over 7\) tells that \(a_7((3,2))=7\). We include Table 3 for \(A_n(\lambda )\) and Table 4 for

for small n in Table 2. In order to verify this it will be convenient to refine Tables 1 and 2 by considering these numbers for fixed partitions \(\lambda \). Specifically we subdivide each case of m from the previous tables according to \(\lambda \), with the m-th composite entry written as a list of entries in the form \((\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \ldots ) \over a_n(\lambda )\) ranging over all \(\lambda \) with \(|\lambda | =m\). Thus for example \((32) \over 7\) tells that \(a_7((3,2))=7\). We include Table 3 for \(A_n(\lambda )\) and Table 4 for  . Neither table is known previously. The \(a_n\) case is computed partly by brute force (and see below); verified in GAP [32], and checked using identity (2)).

. Neither table is known previously. The \(a_n\) case is computed partly by brute force (and see below); verified in GAP [32], and checked using identity (2)).

For the purpose of computing  a better filtration is by the partition describing the size of the connected triangulated regions. But this is even harder to compute in general.

a better filtration is by the partition describing the size of the connected triangulated regions. But this is even harder to compute in general.

7.4 Formulae for  for all n

for all n

In the \(\lambda \) notation Proposition 7.1 becomes

To determine the size of image of the Scott map for a polygon of a given rank, one strategy is to compute  through \(A_n(\lambda )\). While \(A_n(\lambda )\) is also not known in general, we have a GAP code [3, 32] to compute any given case.

through \(A_n(\lambda )\). While \(A_n(\lambda )\) is also not known in general, we have a GAP code [3, 32] to compute any given case.

If in a tiling, there is at most one triangle, we have  . In the case of two triangles, the following result determines

. In the case of two triangles, the following result determines  from tilings of the same type and from tilings where the two triangles are replaced by a quadrilateral:

from tilings of the same type and from tilings where the two triangles are replaced by a quadrilateral:

Proposition 7.5

Let \(\lambda =r^{\alpha _r} (r-1)^{\alpha _{r-1}} \cdots 2^{\alpha _2} 1^{\alpha _1}\).

-

(i)

If \(\alpha _1 < 2\) then

.

. -

(ii)

If \(\alpha _1=2\) then

-

(iii)

If \(\alpha _1=3\) then

-

(iv)

If \(\alpha _1=4\) then

Proof

(ii) Consider partitioning \(A=A_n(\lambda )\) into a subset \(A'\) of tilings where the triangles are adjacent, and \(A''\) where they are not. Evidently  . On the other hand in \(A'\) the triangles form a distinguished quadrilateral. For each element of \(A_n(\lambda 21^{-2})\) we get \(\alpha _2 +1\) ways of selecting a distinguished quadrilateral. There are two ways of subdividing this quadrilateral, thus \(|A'| = 2(\alpha _2 +1) a_n(\lambda 21^{-2})\), and so (ii) is proved. \(\square \)

. On the other hand in \(A'\) the triangles form a distinguished quadrilateral. For each element of \(A_n(\lambda 21^{-2})\) we get \(\alpha _2 +1\) ways of selecting a distinguished quadrilateral. There are two ways of subdividing this quadrilateral, thus \(|A'| = 2(\alpha _2 +1) a_n(\lambda 21^{-2})\), and so (ii) is proved. \(\square \)

Example 7.6

Proposition 7.5 determines  . Here \(A_8(2^2 1^2)\) gives an overcount because of the elements where the two triangles are adjacent. Only one representative of each pair under flip should be kept. These are counted by marking one quadrilateral in each element of \(A_8(2^3)\). There are three ways of doing this, so we have

. Here \(A_8(2^2 1^2)\) gives an overcount because of the elements where the two triangles are adjacent. Only one representative of each pair under flip should be kept. These are counted by marking one quadrilateral in each element of \(A_8(2^3)\). There are three ways of doing this, so we have

from Table 3. Similarly  .

.

(7.7) Proof of (iii): For \(\alpha _1 = 3\) partition \(A=A_n(\lambda )\) into subset \(A'\) of tilings with three triangles together; \(A''\) with two together; and \(A'''\) with all separate. We have  . That is,

. That is,

Considering the triangulated pentagon in a tiling T in \(A'\) as a distinguished pentagon we have

Next aiming to enumerate \(A''\), consider \(\lambda 21^{-2}\), somewhat as in the proof of (ii), but here there is another triangle, which must not touch the marked 4-gon. Let us write \((\alpha _2 +1) A(\lambda 21^{-2})\) to denote a version of \(A(\lambda 21^{-2})\) where one of the quads is marked. There are two ways of triangulating the marked quad, giving \(X=2(\alpha _2 +1) A(\lambda 21^{-2})\), say. Consider the subset B of X of tilings where the marked quadrilateral and triangle are not adjacent.

Claim: \(B \cong A''\).

Proof

The construction (forgetting the mark) defines a map \(B \rightarrow A''\). Marking the adjacent pair of triangles in an element of \(A''\) gives a map \(A'' \rightarrow B\) that is inverse to it. \(\square \)

The complementary subset C of X has quadrilateral and triangle adjacent. Elements map into \(A'\) by forgetting the mark.

Claim: C double counts \(A'\), i.e. the forget-map is surjective but not injective.

Proof

There are 5 ways the quadrilateral and triangle can occupy a pentagon together, and two ways of triangulating the quad. The cases can be written out, and this double-counts the triangulations of the pentagon.

Altogether \( A'' = B = X-C = X-2A' \) so

\(\square \)

(7.8) Proof of (iv): For \(\alpha _1 = 4\) partition \(A=A(\lambda )\) by \( A = A^4 + A^{31} + A^{22} + A^{211} + A^{1111} \) so that

By direct analogy with (7) we claim

Next consider \(X=5(\alpha _3 +1) A(\lambda 31^{-3})\), marking one 5-gon, and then triangulating it. We have a subset B where the 5-gon and triangle are not adjacent; and complement C.

Claim: \(B \cong A^{31}\). This follows as in the proof of part (iii).

The complement C maps to \(A^4\) by forgetting the mark.

Claim: \(14 |C| = 30 |A^4|\).

Proof

There are 6 ways the 5-gon and triangle can occupy a hexagon together, and 5 ways to triangulate the 5-gon. This gives 30 marked cases, which pass to 14 triangulations.

So far we have that

It remains to determine \(A^{22}\) and \(A^{211}\). \(\square \)

(7.9) Next consider \(Y= 4{(\alpha _2 +2) \atopwithdelims ()2} A(\lambda 221^{-4})\), marking two 4-gons, and then triangulating them. Subset D has the 4-gons non-adjacent; and E is the complement.

Claim: \(D \cong A^{22}\). This follows similarly as the statement on B.

The complement E maps to \(A^4\) by forgetting the marks.

Claim: \(14 |E| = 12 |A^4 |\).

Proof

There are 3 ways the 4-gons can occupy a hexagon together, and 4 ways to triangulate them. (NB the map is not surjective—not every triangulation of a hexagon resolves as two quadrilateral triangulations—but we only need to get the count right. We always get 12 out of 14 possible in each case.)

So far we have

Next we need \(A^{211}\). \(\square \)

(7.10) Next consider \(Z=2 (\alpha _2 +1) A(\lambda 21^{-2})\), marking a 4-gon and triangulating it. Subset F has the three parts non-adjacent. Subset G has the 4-gon and one triangle adjacent. Subset \(G'\) has the two triangles adjacent. Subset H has all three parts adjacent:

Claim: \(F \cong A^{211}\). This follows similarly as the statements on B and on C.

The set G maps to \(A^{31}\), and \(G'\) to \(A^{22}\), and H to \(A^4\), by forgetting the marks.

Claim: (a) \( |G| = 2 |A^{31} |\) and (b) \( |G'| = 2|A^{22} |\) and (c) \(14 |H| = 42 |A^4 |\).

Proof

-

(a)

Elements of G pass to tilings with triangulations of a 5-gon and a separate triangle. The collection of them triangulating a given 5-gon and triangle has order 10 (5 ways to mark a quadrilateral in the 5-gon, then two ways to triangulate it). On the other hand the number of triangulations of the same region in \(A^{31}\) is 5.

-

(b)

Elements of \(G'\) pass to tilings with triangulations of two 4-gons. The collection of such gives all these triangulations. Each one occurs twice in \(G'\) since the triangulation of the two 4-gon regions can arise in \(G'\) with one or the other starting out as the marked 4-gon.

-

(c)

Elements of H pass to tilings with triangulations of a hexagon. The collection of such gives \(A_6(21^2) = 21\) ways of tiling the hexagon with quadrilateral and two triangles, then two ways of tiling the quad. On the other hand there are 14 triangulations of this hexagon in \(A^4\).

We have \( A^{211} = Z-(G+G'+H) = 2 (\alpha _2 +1) A(\lambda 21^{-2}) - ( \frac{2}{1} A^{31} + \frac{2}{1} A^{22} +\frac{42}{14} A^4 ) . \)

Altogether now

\(\square \)

Remark 7.11

In [2] we prove the following generalisation of Proposition 7.5

where \(\mu = r^{\alpha _{r}(\mu )} (r-1)^{\alpha _{r-1}(\mu )} \ldots 2^{\alpha _{2}(\mu )} 1^{\alpha _{1}(\mu )}\).

7.5 Tables for

Proposition 7.12

The numbers  for \(n<11\) are given in Table 2.

for \(n<11\) are given in Table 2.

Proof

The numbers \(a_n(\lambda )\) are given in Table 3 by a GAP calculation [3]. The numbers in Table 4 then follow from formula (5) and Proposition 7.5. Table 2 follows immediately. \(\square \)

7.6 On asymptotics

We determined in Tables 2, 4 the sizes of the image of the Scott map in low rank. Of course the ratio of successive sizes of the formal codomains grows with n as \(|\Sigma _n| / |\Sigma _{n-1} | = n\). In the next table we consider the ratios of two consecutive entries of the sequence  .

.

n | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 7 | 26 | 100 | 404 | 1691 | 7254 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 3.71 | 3.85 | 4.04 | 4.19 | 4.29 |

(7.13) A paradigm for this is the Catalan combinatoric \(C_n\) (see e.g. [31]), which can also be equipped with an inclusion in the permutations \(\Sigma _n\)—see e.g. [19, 29] (NB this inclusion is not related to the inclusion in \(A_n\) already noted). It is straightforward in this case to verify that the asymptotic growth rate is 4.

n | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\(|C_n|\) | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 42 | 132 | 429 | 1430 |

\(|C_n|/|C_{n-1}|\) | 2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3 | 3.14 | 3.25 | 3.33 |

This raises the question: Is there a limit rate in the  case?

case?

8 On enumerable classes of strand diagrams and plabic graphs

Let \({\mathsf {Pb}}_n\) be the set of reduced plabic graphs [26, §11] of rank-n; and \({\text {Po}}_n\) be the set of alternating strand diagrams as in [26, §14]. (See also Sects. 8.1 and 8.5.) Their relationship with \(A_n\) can be summarized as follows:

Here \({\mathsf {G}}\) is as in Sect. 1, \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) as in Sect. 2.1, and \(D,D'\) as in Sect. 8.2. In this section we apply Theorem 2.1 to corresponding subsets of plabic and strand diagrams. We define the sets \(\mathcal {X}_n\) of \(minimalist\) strand diagrams, see Sect. 8.1; and \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) of \(rhombic\) (plabic) graphs, see (8.5). We will show that these sets are in bijection with \(A_n\).

For the sake of brevity we refer to Postnikov’s original paper for motivations behind the constructions of plabic and strand diagrams themselves. These are large and complex classes of objects, and canonical forms for them would be a useful tool. The rigid/canonical nature of \(A_n\) induces canonical forms for (the restricted cases of) the other constructions.

We start by characterizing the image of \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) in Theorem 8.4 as the set of minimalist strand diagrams and hence show that \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) is injective. In Sect. 8.2 we recall Postnikov’s bijections between alternating strand diagrams and plabic graphs. (An illustration of the connection between plabic graphs and strand diagrams is given by Fig. 12b.) This allows us to characterize the image of \({\mathsf {G}}\) in Sect. 8.3 as the set of rhombic plabic graphs, Theorem 8.19. Finally we determine the images of flip equivalence in the two other realisations.

8.1 On \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) and strand diagrams

An absolute strand diagram on (S, M) is a Jordan diagram such that: (i) strands crossing a given strand must alternate in direction; (ii) if two strands cross twice such as to cut out a simple disk then the resultant loop is oriented; (iii) if a strand is self-crossing then no resultant loop is a simple disk; (iv) no strand is a closed loop cutting out a simple disk.

Note that this agrees with the ordinary definition of \(alternating strand diagram\) [4, 26] for S a simple disk. Here rank \(n= | M_\partial |=|M|\).

For any directed planar graph we classify the faces as clockwise, counterclockwise, alternating or other.

(8.1) Let \(\mathcal {X}_n\) be the subset of rank-n alternating strand diagrams whose faces are as follows: (i) n clockwise faces at the boundary, labelled \(1,2,\dots , n\) going clockwise around the boundary; (ii) alternating faces with four sides; (iii) oriented faces in the interior that are counterclockwise and have at least 3 sides.

We call the elements of \(\mathcal {X}_n\) \(minimalist\) strand diagrams. See Fig. 13 for an example.

(8.2) Note that an element of \(\mathcal {X}_n\) (as every alternating strand diagram) has a chequerboard colouring of faces (see e.g. [26]). If a clockwise face is black (say) then all oriented faces are black and all alternating faces white. Also the faces around an alternating face alternate clockwise/counterclockwise.

(8.3) We define a ‘shrink’ map \({\mathsf {f}}:\mathcal {X}_n\rightarrow A_n\) as follows: Let \(d\in \mathcal {X}_n\). Note from (8.2) that in d regarded as an isotopy class of concrete diagrams there are cases in which all the edges of clockwise faces are arbitrarily short. Thus the clockwise faces are arbitrarily small neighbourhoods of n points; and alternating faces have two short edges and two edges that pass between the clockwise faces (and hence are not short). The paths of non-short edges are not constrained by the ‘shrinking’ of the clockwise edges. Thus each pair may be brought close to each other, and hence form an arbitrarily narrow neighbourhood of a line between two of the n points. Since no two alternating faces intersect, these lines cannot cross, and so they form an element of \(A_n\).

Theorem 8.4

The map \({\mathsf {f}}:\mathcal {X}_n\rightarrow A_n\) is the inverse to a bijection \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!:A_n\rightarrow \mathcal {X}_n\).

Proof

It will be clear that \({\mathsf {f}}\) makes sense on \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!(T)\) since it even makes sense tile by tile (cf. Fig. 14). Indeed it recovers the tile, so \({\mathsf {f}}\) inverts \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\). The other steps have a similar flavour. \(\square \)

Remark. One can prove more generally, that \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) is injective on tilings of (S, M) and that the image of any tiling of (S, M) is an absolute strand diagram.

8.2 Maps \(D,D'\) between strand diagrams and plabic graphs

(8.5) A plabic graph \(\gamma \) is a planar, disk-embedded undirected graph with two ‘colours’ of vertices/nodes, considered up to homotopy [26, Definition 11.5]. Vertices are allowed on the disk boundary. The rank of \(\gamma \) is the number of these ‘tagged’ vertices. In rank n they are labelled \(\{1,2,\ldots ,n \}\) clockwise.

Postnikov defines ‘moves’ on plabic graphs in [26, §12]:

with M2-3 also for black nodes. In M2 any number of incoming edges is allowed. Postnikov also defines reductions on plabic graphs:

and similarly with colours reversed. The move-equivalence class of \(\gamma \) is its orbit under (M1-3). A plabic graph of rank n is reduced if it has no connected component without boundary vertices; and if there is no graph in its move-equivalence class to which (R1) or (R2) can be applied. See [26, §12] for details.

We write \({\mathsf {Pb}}_n\) for the set of reduced plabic graphs of rank n.

Recall the map \({\mathsf {G}}\) on \(A_n\) to plabic graphs from Sect. 1. If T is a tiling of an n-gon, we draw a white node at each vertex of the polygon and a black node in each tile, connecting the latter by edges with the white nodes at the vertices of the tile. One can see that the graph produced has no parallel bicoloured edges and no internal leaves with bicoloured edges. Thus \({\mathsf {G}}:A_n\rightarrow {\mathsf {Pb}}_n\).

Postnikov’s plabic networks are generalisations of the above including face weights. Here it will be convenient to consider another kind of generalisation.

(8.6) For any planar graph L there is a medial graph \({\mathsf {m}}(L)\) (see e.g. [5, §12.3]), which is a planar graph distinct from but overlaying L. We obtain \({\mathsf {m}}(L)\) by drawing a vertex \({\mathsf {m}}(e)\) on each edge e of L, then whenever edges \(e,e'\) of L are incident at v and bound the same face we draw an edge \({\mathsf {m}}(e)\)-\({\mathsf {m}}(e')\).

(8.7) For \({\mathsf {m}}(L) \) we note the following. (1) \({\mathsf {m}}(L)\) has a polygonal face \(p_v\) around each vertex v of L. (2) Monogon and digon faces are allowed—see Fig. 15 (so edges may not be straight). (3) The faces of \({\mathsf {m}}(L)\) are of two types: containing a vertex of L, or not. Given an asignment of a colour (black/white) to each vertex of L then we get a digraph \(\overrightarrow{{\mathsf {m}}}(L)\) by asigning an orientation to each polynomial face: counterclockwise if v is black and clockwise otherwise. (4) If L is bipartite and indeed 2-coloured then for this asignment the orientations in \(\overrightarrow{{\mathsf {m}}}(L)\) have the property that we may reinterpret the collection of meeting oriented polygons as a collection of crossing oriented strands, denoted \(D_L\).

(8.8) Suppose L has some labelled exterior vertices. A ‘half-edge’ or ‘tag’ may be attached to any such vertex v (specifically one usually thinks of L bounded in a disk in the plane, and the tag as an edge passing out through the boundary) whereupon there is a medial vertex \({\mathsf {m}}(v)\) on the half-edge, and the (exterior) medial edge around v becomes two segments incident at \({\mathsf {m}}(v)\). In this case, if v is labelled in L then we say that \({\mathsf {m}}(v)\) inherits this label in \({\mathsf {m}}(L)\).

(8.9) Noting (8.7) and (8.8), the map

may be defined by \(D(L)=D_L\).

(8.10) A fully reduced plabic graph is a reduced plabic graph without non-boundary leaves; and without unicolored edges. In particular it is a connected 2-coloured planar graph. Write \({\mathsf {Pf}}_n\) for the set of fully reduced plabic graphs of rank n.

Postnikov’s Corollary 14.2(1) can now be summarized as: \(L \mapsto D_L\) restricts to a bijection \(D: {\mathsf {Pf}}_n \rightarrow {\text {Po}}_n\).

(8.11) Postnikov gives a map

as follows, that inverts D. Let d be an alternating strand diagram. Then \(D'(d)=\gamma _d\) is the plabic graph we obtain by drawing a white vertex in each clockwise oriented face and a black vertex in each counterclockwise face. Two vertices are connected by an edge if and only if their faces are opposite each other at the crossing point of a pair of crossing strands. (Example: Fig. 12.)

8.3 Properties of the map \({\mathsf {G}}\)

We note that \({\mathsf {G}}\) is the composition \(D' \circ {\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\). Since \(D'\) is a bijection and \({\overrightarrow{\varvec{\sigma }}}\!\) is injective (Theorem 8.4), \({\mathsf {G}}\) is injective. In this section, we give an intrinsic characterization of the image of \({\mathsf {G}}\).

(8.12) Let u and v be two black nodes in \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pf}}_n\) that are on a common quadrilateral. If u has degree \(r+2\) and is incident with \(r\ge 1\) leaves, we say that \(\gamma \) has an r-\(bouquet\) at u or a \(bouquet\) at u. The subgraph on the quadrilateral and on the r leaves is the bouquet at u.

The first figure below is a bouquet at u with 4 leaves. The second figure shows two (non-disjoint) bouquets, one at u and one at v. The second graph has two bouquets. It satisfies the conditions for \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) of Definition 8.13.

Definition 8.13

The set \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) of \(rhombic\) graphs is

the set of connected fully reduced plabic graphs \(\gamma \) in \({\mathsf {Pf}}_n\) containing at least one black node and such that

(a) the tagged nodes (in the sense of (8.5)) are white and all other nodes are black,

(b) every black node has degree \(\ge 3\),

(c) every closed face is a quadrilateral,

(d) in the fan of edges coming out of a white node every adjacent pair is part of a quadrilateral.

(8.14) We observe that conditions (a) and (b) imply: (e) Two faces of a rhombic graph share at most one edge.

For \(n=3,4,5\), \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) has 1,3,11 elements respectively, cf. Fig. 16.

Lemma 8.15

If \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\), \(\gamma \) not a star, then \(\gamma \) has at least two bouquets.

Proof

Forget the leaves for a moment, so we have graph of quadrilaterals. (Cf. [24].) Now consider the exterior ‘face‘ subgraph - a 2-coloured loop. We see (e.g. by induction on number of faces, using (8.14)) that this must have at least 2 black corners (black nodes touching only 1 quadrilateral). \(\square \)

We note that \({\mathsf {G}}(A_n) \subseteq {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\). Our next goal is to get an inverse to the map \({\mathsf {G}}\), going from rhombic graphs to tilings. One ingredient is the following lemma which says that if we split an element of \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) at a bouquet at node u, we obtain a star graph and an element \(\gamma _u\) of \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\).

(8.16) Let \(\gamma \) be a plabic graph containing a bouquet at vertex u, with u of degree \(r+2\). Define \(\gamma _u\) as the full subgraph on the vertex set excluding u and its leaves. We denote by \(\gamma _s\) the full subgraph on u and all white nodes incident with u.

For example here \(\gamma _s\) is the upper graph on the right and \(\gamma _u\) is the lower graph on the right.

Lemma 8.17

Let \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\), \(\gamma \) not a star. If \(\gamma \) has a bouquet at u then \(\gamma _u\in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\).

Proof

Note that \(\gamma _u\) inherits (a) and (b) of Definition 8.13 from \(\gamma \). Denote the second black node of the bouquet at u by v. When splitting, the quadrilateral face involving u and v becomes a boundary face of \(\gamma _u\). All other faces of \(\gamma _u\) are faces of \(\gamma \). So (c) also holds.

It remains to see that (d) holds for \(\gamma _u\). The only vertices to check are i and \(i+r+1\). In \(\gamma \), every adjacent pair of edges at i (or at \(i+r+1\) respectively) are part of a quadrilateral. When going to \(\gamma _u\), one extremal edge of the fan is removed, so the remaining edges still satisfy (d). \(\square \)

(8.18) Let \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\). Consider the set

Note (by 8.13(a) and the construction) that this forms a collection of pairwise non-crossing diagonals of an n-gon. We denote this tiling \(T={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )\).

Theorem 8.19

The map \({\mathsf {G}}'\) is the inverse to a bijection \({\mathsf {G}}\): \(A_n\rightarrow {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\).

Proof

We will show that \({\mathsf {G}}{\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )=\gamma \) for every \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\).

We use induction on n. If \(n=|\gamma |=3\), by Definition 8.13, \(\gamma \) does not contain any quadrilaterals, hence is a star, and \({\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )\) is the untile T of a triangle, with \(G(T)=\gamma \). So assume that the claim is true for \({\mathsf {Pt}}_{n-1}\). Take \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\). If \(\gamma \) is a star, \(T={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )\) is the untile of the n-gon and \({\mathsf {G}}(T)=\gamma \). So assume \(\gamma \) is not a star. By Lemma 8.15, it then contains at least two bouquets, say an r-bouquet for some \(1\le r< n-2\).

We split \(\gamma \) at the bouquet and obtain a star \(\gamma _s\) and the graph \(\gamma _u\). Let the white nodes of this star be \(i,i+1,\dots , i+r+1\) (reducing mod n). Then the white nodes of \(\gamma _u\) are \(i+r+1, i+r+2,\dots , i\) (reducing mod n). Graphs \(\gamma _s\) and \(\gamma _u\) are elements of \({\mathsf {Pt}}_{r+2}\) (with \(r+2<n\)) and \({\mathsf {Pt}}_{n-r}\) respectively by Lemma 8.17. So by induction for the tilings \(T_s={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma _s)\) and \(T_u={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma _u)\) of polygons we have \({\mathsf {G}}(T_s)=\gamma _s\) and \({\mathsf {G}}(T_u)=\gamma _u\).

Tiling \(T_s\) is the untile of the polygon \(P_s\) on the vertices \(i,i+1,\dots , i+r+1\); \(T_u={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma _u)\) a tiling of the polygon \(P_u\) on the vertices \(i+r+1, i+r+2,\dots , i\).

We glue the two polygons \(P_s\) and \(P_u\) along the boundary edges \([i+r+1,i]\) and \([i,i+r+1]\) to obtain an n-gon P with vertices \(1,2,\dots , n\) and tiling T given by the union of the diagonals of \(T_s\), \(T_u\) and diagonal \([i,i+r+1]\).

Since T contains a diagonal exactly for every quadrilateral in \(\gamma \), \(T={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )\). By construction, \({\mathsf {G}}(T)=\gamma \). \(\square \)

8.4 \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) and equivalence classes under moves

(8.20) We define ‘moves’ \(\rho _{\diamond }\) on elements of \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) as in Fig.17 (these moves are a particular combination of M1 and M2 from Sect. 8.2).

Lemma 8.21

Under the bijection \({\mathsf {G}}':{\mathsf {Pt}}_n\rightarrow A_n\), a move \(\rho _{\diamond }\) corresponds to a flip in a tiling.

Proof

Consider \(\gamma \in {\mathsf {Pt}}_n\), let \(T={\mathsf {G}}'(\gamma )\). Any quadrilateral \(\diamond \) in \(\gamma \) corresponds to a diagonal \([p_1,p_3]\) in T. Now assume that two black nodes \(u_1,u_2\) of the quadrilateral \(\diamond \) have degree three and let \(p_2\), \(p_4\) be the other two white nodes adjacent to the black nodes of \(\diamond \). Then the four full subgraphs \(p_i,u_j,p_{i+1}\) (with i, j appropriate) of \(\gamma \) are either boundary paths or part of quadrilaterals. In the former case, the image of \(\gamma \) under \({\mathsf {G}}'\) has a boundary segment \([p_i,p_{i+1}]\); in the latter case, it has a diagonal \([p_i,p_{i+1}]\). In any case, T contains a triangulated quadrilateral \(p_1,p_2,p_3,p_4\) with diagonal \([p_1,p_3]\) and the move \(\rho _{\diamond }\) corresponds to the exchange \([p_1,p_3]\longleftrightarrow [p_2,p_4]\) in T. \(\square \)

Given Lemma 8.21 we can then define move-\(\rho _{\diamond }\) equivalence classes \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n/\sim \) on \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\). Furthermore, the number of equivalence classes are the same as  .

.

For \(n=3,4,5\), one can readily confirm 1, 2, 7 classes respectively using Fig. 18. (Although this does not provide any obvious new method to compute in higher ranks, cf. Sect. 7.)

(8.22) On strand diagrams, flip corresponds to a combination of moves from Fig. 19 (recalled from [26, §14])—the combination given in Sect. 2.1.

(8.23) There are many beautiful set sequences in the little Schröder combinatoric [31] (\(A_n\) is a standard one, to which we have now added \({\mathsf {Pt}}_n\) and \(\mathcal {X}_n\)). It is one nice problem for future consideration to recast flip equivalence into cases such as Schröder’s original bracket sequences (the set \(\Omega _n\) is the set of properly nested bracketings on a word of length \(n-1\), where there is always an (undrawn) outer bracketing and otherwise each bracket pair must contain at least two symbols—the bijection with \(A_n\) is elementary via rooted versions of the dual trees of Sect. 3). As a taste of this game, the first few in this case are as follows: \( \Omega _3 = \{ ab \}, \; \Omega _4 = \{ abc,(ab)c,a(bc) \}, \; \) and in A-complex form

Here flip equivalence collapses the entire first row to a point.

Notes

Department of Mathematics, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

References

Balsam, B., Kirillov, A. Jr.: Turaev-Viro invariants as an extended TQFT. arXiv:1004.1533v3

Baur, K., Martin, P.P.: A generalised Euler-Poincaré formula for associahedra (2017). arxiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.04

Baur, K., Martin, P.P.: GAP macros refining the Fuss–Euler combinatoric, GAP code available at http://www1.maths.leeds.ac.uk/~ppmartin/GRAD/NOTES/COMBINATORICS/GRaZ.g (2015)

Baur, K., King, A.D., Marsh, R.J.: Dimer models and cluster categories of Grassmannians. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. (3) 113(2), 213–260 (2016)

Baxter, R.: Exactly Solved Models in Statistical Mechanics. Academic Press, Cambridge (1982)

Bessenrodt, C.: Conway–Coxeter friezes and beyond: polynomially weighted walks around dissected polygons and generalized frieze patterns. J. Algebra 442, 80–103 (2015)

Bondy, J.A., Murty, U.S.R.: Graph Theory, GTM244. Springer, Berlin (2007)

Brüstle, T., Zhang, J.: On the cluster category of a marked surface without punctures. Algebra Number Theory 5(4), 529–566 (2011)

Buchstaber, V.: Fullerenes and polygonal partitions of surfaces. In: Workshop on Analysis, Geometry and Probability, Ulm (2015) (online, workshop September–October 2015)

Flajolet, P., Sedgewick, R.: Analytic Combinatorics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2009)

Fock, V., Goncharov, A.: Dual Teichmüller and lamination spaces. In: Papadopoulos, A. (ed.) Handbook of Teichmüller Theory, vol. 1, pp. 647–684. Eur. Math. Soc., Zürich (2007)

Fomin, S., Shapiro, M., Thurston, D.: Cluster algebras and triangulated surfaces. Part I: cluster complexes. Acta Math. 201, 83–146 (2008)

Harer, J.L.: Stability of the homology of the mapping class groups of orientable surfaces. Ann. Math. 121, 215–249 (1985)

Hatcher, A.: On triangulations of surfaces. Topol. Appl. 40, 189–194 (1991)

Ivanov, N.V.: Mapping class groups. In: Daverman, R.J., Sher, R.B. (eds.) Handbook of Geometric Topology, pp. 523–633. North-Holland, Amsterdam (2002)

Kadar, Z., Martin, P., Yu, S.: On geometrically defined extensions of the Temperley-Lieb category in the Brauer category (2014). arxiv, http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.1774

Kirillov Jr., A.: On piecewise linear cell decompositions. Algebr. Geom. Topol. 12(1), 95–108 (2012)

Kitaev, A.: Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2005)

Knuth, D.E.: Sorting and Searching. The Art of Computer Programming, vol. 3, 2nd edn. Addison Wesley, Boston (1998)

Lando, S.K., Zvonkin, A.K.: Graphs on Surfaces. Springer, Berlin (2004)

Macdonald, I.G.: Symmetric Functions and Hall Polynomials. Oxford Classic Texts in the Physical Sciences, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Marsh, R., Martin, P.: Pascal arrays: counting Catalan sets (2006). arxiv, http://arxiv.org/pdf/math/0612572v1.pdf

Moise, E.E.: Geometric Topology in Dimensions 2 and 3. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 47. Springer, New York (1977)

Musiker, G., Schiffler, R., Williams, L.: Positivity for cluster algebras from surfaces. Adv. Math. 227(6), 2241–2308 (2011). MR2807089

Petersen, T.K., Pylyavskyy, P., Rhoades, B.: Promotion and cyclic sieving via webs. J. Algebr. Comb. 30(1), 19–41 (2009)

Postnikov, A.: Total positivity, Grassmannians, and networks. Preprint (arXiv:math/0609764)

Propp, J.: The combinatorics of frieze patterns and Markoff numbers (2005). http://arxiv.org/pdf/math/0511633v4.pdf

Przytycki, J.H., Sikora, A.S.: Polygon dissections and Euler, Fuss, Kirkman and Cayley numbers. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 92(1), 68–76 (2000). arXiv:math/9811086v1

Reading, N.: Clusters, Coxeter-sortable elements and non-crossing partitions. Trans. AMS 359, 5931–5958 (2007). (See also: Catalan, 321-perm, talk online)

Scott, J.: Grassmannians and cluster algebras. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 92(2), 345–380 (2006)

Stanley, R.P.: Enumerative Combinatorics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1997)

The GAP Group: GAP—Groups, Algorithms, and Programming, Version 4.7.9 (2015)

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). We thank Henning H. Andersen, Aslak B. Buan and Walter Mazorchuk and the Mittag-Leffler Institute for inviting us to the 2015 Semester on Representation Theory, where this work was started. We thank Robert Marsh and Hannah Vogel for useful comments on the manuscript. PM would like to thank EPSRC for partial funding under the grant EP/I038683/1 “Algebraic, Geometric and Physical underpinnings of Topological Quantum Computation”. KB would like to thank FWF for partial funding under projects P25141-N26, P 25647-N26 and W1230. We thank the referees for numerous helpful suggestions. KB thanks Peter Grabner for useful conversations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by A. Constantin.

Appendix A. The number of ‘Scott permutations’

Appendix A. The number of ‘Scott permutations’

1.1 Max Glick Footnote 1 (as interpreted by KB, PPM)