Abstract

Purpose

This study, set in in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, describes the epidemiology and outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) followed by home-based rehabilitation alone.

Methods

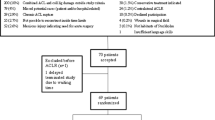

A cohort observational study of patients aged ≥ 16 years with an ACL rupture who underwent an ACLR under a single surgeon. Followed by a home-based rehabilitation programme of appropriate simplicity for completion in the home setting; consisting of stretching, range of motion and strengthening exercises. Demographics, mechanism of injury, operative findings, and outcome data (Lysholm, Tegner Activity Scale (TAS), and revision rates) were collected from 2016 to 2021. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results

The cohort consisted of 545 patients (547 knees), 99.6% were male with a mean age of 27.8 years (SD 6.18 years). The mean time from diagnosis to surgery was 40.6 months (SD 40.3). Despite data attrition Lysholm scores improved over the 15-month follow-up period, matched data showed the most improvement occurred within the first 2 months post-operatively. Post-operative TAS results showed an improvement in level of function, but did not reach pre-injury levels by final follow-up. At final follow-up, six (1.1%) patients required an ACLR revision.

Conclusion

Patients who completed a home-based rehabilitation programme in Kurdistan had low revision rates and improved Lysholm scores 15 months post-operatively. To optimise resources, further research should investigate the efficacy of home-based rehabilitation for trauma and elective surgery in low- to middle-income countries and the developed world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The annual incidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears is estimated to be 68.6 per 100,000 person-years in an American-based study [1]. In Iraq, equivalent statistics are unavailable because credible data are not systematically collected and/or paper-based systems are utilised which are inappropriate for data analysis [2, 3]. Consequently, there is limited understanding of the epidemiology and financial burden of musculoskeletal problems in both Iraq and other low- to middle-income countries (LMIC) [4]. ACL ruptures are likely to represent a common injury in Iraq due to its relatively young population (median age 21.7 years) [5, 6] and the popularity of football [5].

Iraq is an economically developing country [6] in which the quality of health care has declined over the past 30 years as a result of multiple wars and embargoes [3]. Kurdistan is an autonomous region of Iraq which has become a safe place for many refugees and internally displaced people resulting in increasing pressure on local health care [3]. It is envisaged that improved information management systems, a trained workforce and specialised equipment are needed to improve health care provision in this region [2].

The generic aims of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) are to improve function, quality of life, prevent further injury, osteoarthritis, and enable patients to resume sport and/or work [7]. In developed countries physiotherapists or rehabilitation specialists play a critical role in facilitating the rehabilitation required to return patients to pre-injury function [7]. However, in Iraq this approach is problematic because of the limited number of physiotherapists [8, 9]. Furthermore, patients often forego physiotherapy to afford the costs of an ACLR. To address such challenges the surgeon in Kurdistan provides patients with instruction on a home-based ACL rehabilitation programme.

This study is reporting on a unique experience of a specialist knee surgeon in Kurdistan who has established and maintained his own ACL database to monitor, inform and improve the outcomes of his ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery.

The aims of this study are to describe the epidemiology and outcomes for patients in Kurdistan who underwent an ACL reconstruction and completed a home-based rehabilitation programme over a 5-year period.

Method

This is an observational cohort study of patients who underwent an ACLR and completed a home exercise programme in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Data were collected as part of the surgeon’s routine practice and patient follow-up.

The study included all patients aged ≥ 16 years who had an MRI confirmed ACL rupture and underwent ACLR during the study period (November 2016–November 2021). Patients were excluded from this study if they had concomitant posterior cruciate ligament injuries, multi-ligament injuries or fractures.

Surgery and home-based rehabilitation programme

All ACLRs were performed arthroscopically by the same surgeon using a hamstring autograft and the following method: The knee is examined under anaesthesia to confirm isolated ACL rupture. Intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g is given at induction, followed by 160 mg Gentamicin at tourniquet deflation. An anteromedial longitudinal incision over the pes anserinus insertion is utilised. The sartorius fascia is incised at the superior border of the gracilis tendon. Both gracilis and semitendinosus tendons are identified and soft tissue accessory attachments released. Both tendons are harvested using a closed tendon stripper and detached from the tibia. The tendons are then prepared as a four to six strand graft with "whip stitching" depending on thickness, achieving a minimum of 8 mm in graft diameter. The graft is then stored in moist saline soaked gauze.

Systematic examination of the knee is carried out with the arthroscope after creating an accessory anteromedial working portal under direct vision. The arthroscopic shaver and curette are used to debride residual ACL tissue from the lateral wall and posterior aspect of the notch. An entry point is made on the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle using a microfracture awl. The knee is flexed to more than 110°. Long 2.4 mm guide wires with suture eyes are passed, exiting through the anterolateral skin of the thigh. The femoral tunnel is over-drilled with a 4.5 mm drill and then drilled again with a larger cannulated drill matching the graft dimeter. A minimum of 20–30 mm length of graft in the tunnel was deemed acceptable. The Acufex (Smith + Nephew) drill guide is used, set at 45–55° depending on the graft length. The tibial guide is placed on the ACL footprint, under arthroscopic vision. The same sequence of drilling is applied. Residual ACL tissue is removed from the tunnel margins. The graft is then passed and inspected for lateral wall or roof impingement. An RCI titanium (Smith & Nephew) interference screw (7 × 25 mm standard or reverse thread) or an Endobutton device is used for the femoral side. Either an RCI titanium interference screw or (Bio) RCI screw is used to fix the tibial side in full extension. Additional tibial fixation with suture disc or staple (10 mm) was used if there were any concerns about tibial bone quality. The knee is inspected and graft tension assessed. Range of motion and pivot shift are checked. Copious washout is performed followed by closure using 3:0 undyed Vicryl.

Following ACLR patients completed a home exercise programme. The surgeon provided each patient with a written (booklet) and video instruction (DVD, YouTube, Facebook) of the home-based rehabilitation programme available in Arabic, English and Kurdish. All exercises on the video instruction were demonstrated by the NGMV medical volunteers rehabilitation team (a UK registered charity) [10]. Table 1 provides an outline of the home exercise programme which an appropriate level of simplicity for completion in the home setting. The home-based programme consists of stretching, range of motion and strengthening exercises which are proven to be the most important exercises in improving outcomes [11, 12]. Exercises are divided into four stages: 0–3 weeks, 3–6 weeks, 6–12 weeks and 12–24 weeks. Although timescales are indicated throughout the programme, stages 3 and 4 rely on criteria-based progression (specific criteria that need to be achieved before patients can progress to the next stage of rehabilitation) [13].

Data collection

Demographic data collection included the patient’s age, gender, height, weight and occupation. Details were also recorded about their injury (dominant limb, mechanism of injury, and date of injury) and the operation (tourniquet time, time to surgery and the surgical procedure). See Table 2 for all details.

Outcome measures

When assessing the outcome of surgery the revision rate was regarded as the primary determining factor in addition to Lysholm and Tegner scores. The Lysholm is a rating scale (0–100), with higher scores indicating less symptoms and better levels of function [14]. The Tegner activity scale (TAS) (0–10) quantifies the highest current level of activity achievable by the patient with higher scores representing function at a demanding level of competitive sport (e.g. national elite football) [14]. Lysholm scores, mid-thigh girth and the Lachman’s tests were completed by the operating surgeon pre-operatively (at the time of initial clinic assessment) and repeated at 2, 6, 9 and 15-months post-operatively. TAS scores were recorded by the operating surgeon to include pre-injury, post-injury (at time of clinic assessment) and final follow-up, which varied for each patient. The Lysholm questionnaire and TAS are not validated for use in the native Kurdish language therefore an English version was used and some patients required help from the surgeon to interpret the questions.

ACLR failure was determined by patient reported instability and clinical findings of laxity on examination. All patients who had recurrence of instability had a repeat MRI scan to confirm diagnosis of graft failure and the need for revision. Due to limited number of specialist knee surgeons in Kurdistan, it is likely that all patients would return to the operating surgeon in this study if they had further problems following the ACLR. To confirm this, in June 2022 a telephone review was conducted to determine whether any patients had undergone a repeat arthroscopy, ACL revision or experienced pain and/or functional difficulties that were not reported at follow-up. Due to the different operation dates within the cohort the minimum telephone follow-up was 6 months and the maximum was for 5.5 years.

Data analysis

Data were cleaned and anonymised. Descriptive statistics (number, percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD)) were calculated using Excel Version 16.61.1. Occupation was categorised into the following groups: hospitality services, skill/craft work, medical professional/Industry, military, sport and leisure industry, manual labour, retail industry/services, police and security, education, administration, professionals, housewife, and managers. Mechanism of injury was categorised as: falls, team sports (handball, volleyball, and basketball), and contact sport, road traffic accidents and other. Surgical findings were categorised according to those identified in the patellofemoral, medial, and lateral compartments.

Results

From November 2016 to November 2021, 547 ACLRs were performed in 545 patients (two patients had bilateral ACL injuries, operated on at separate times). The demographics, injury and operative details are described in Table 2. All procedures were performed by a single senior surgeon. ACL injuries occurred almost exclusively in males (n = 543, 99.63%), who injured their dominant limb playing soccer (90.9%). The average age was 27.87 (SD 6.18) and the average time to operation from date of injury was 40.6 months (SD 40.3).

Table 3 shows categorisation of the intra-operative findings for 547 knees. Only one patient had a partial ACL tear, and the remainder had full ACL tears. Just over half the cohort presented with medial meniscal injuries and approximately a third with lateral meniscus injuries.

Table 4 presents mean Lysholm scores and mid-thigh girth pre-operatively and post-operatively at the different follow-up intervals (2, 6, 9 and 15 months). Outcome data are presented for the full cohort at each follow-up, with data attrition (not all patients attended at every follow-up interval). Despite data attrition over the 15 month follow-up period average Lysholm scores showed overall improvement throughout the follow-up intervals from 72.11 (SD 12.66) at baseline to 91.9 (SD 8.58) at 15 months. Matched data were available for patients who attended both pre- and post-operative follow-up. Matched data showed the greatest improvement occurred within the first 2 months post-operatively increasing by 6.33 points a month from a baseline of 72.28 (n = 240, SD 12.42) to 84.94 (n = 240, SD 6.89).

For matched patients at 6 months follow-up: Lysholm scores increased from 72.76 (n = 349, SD 12.15) to 90.31 (n = 349, SD 7.05)); at 9 months from 72.96 (n = 248, SD 12.03) to 91.85 (n = 248, SD 7.39); and at 15 months from 72.10 (n = 129, SD 12.62) to 91.98 (n = 129, SD 8.57). The highest Lysholm scores were attained at 9 and 15 months post-operatively (after the home programme was completed).

Table 4 presents mean mid-thigh girth of the injured limb pre-operatively and post-operatively at the same follow-up intervals, with data attrition. This reduced by over a centimetre and half at 2 months post-operatively, however by 9 months pre-operative girth was exceeded. Matched data were also available for patients who attended both pre- and post-operative follow-up. Matched data showed a decrease in mid-thigh girth at 2 months from 56.03 (n = 406, SD 5.15) to 54.91 cm (n = 406, SD 5.51); at 6 months follow-up from 55.79 (n = 325, SD 5.08) to 55.35 cm (n = 325, SD 5.17); and at 9 months from 56.21 (n = 213, SD 5.08) to 56.08 cm (n = 213, SD 4.58). In contrast to unmatched data, matched thigh girth was not regained until 15 months, increasing from 56.36 (n = 92, SD 4.96) to 56.65 cm (n = 92, SD 4.37).

Table 4 also presents mean thigh girth difference measured at baseline and at follow-up, with data attrition. Mean thigh girth difference was calculated from injured side mid-thigh girth subtracted by contralateral side mid-thigh girth, in centimetres. Findings closely mirror those reported above, with an initial increase in thigh girth difference, followed by a significant improvement with the injured side being within 0.23 cm (SD 1.35) of the contralateral side by 9 months.

Table 5 presents pre-injury, post-injury, and post-operative TAS scores. The post-operative final follow-up Tegner scores improved compared to the post-injury scores, but patients did not reach their pre-injury levels of function.

Table 6 outlines the outcome of the telephone review to determine re-rupture rates. 484 (88.5%) knees required no further surgery with the patient satisfied with the outcome. Six males with a mean age of 22.2 years (SD 3.9) required an ACL revision and one had the revision completed within the timeframe of the study. In four cases ACL graft failure was caused by return to sport or strenuous physical activities prior the time frame recommended by the surgeon, in the other two cases the cause for failure was unknown.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is one of the first studies to describe the epidemiology and outcomes for patients who underwent ACLR in Kurdistan, Iraq. In this region ACL injuries occur almost exclusively in males, with a mean age of 27.8 years and were sustained playing soccer. Following the completion of a home-based exercise programme re-rupture rates were low (1.1%), and Lysholm scores improved over the 15 months follow-up period, with the most marked improvement in the first 2 months after ACLR. At the final follow-up, TAS scores had not returned to pre-operative activity levels.

The mean age of injury (27.8 years) aligns with that reported in previous studies [1]. However, the occurrence of ACL injuries almost exclusively in males is a novel finding, contrasting with 41% females reported in a large cohort study [1]. Despite the positive steps to increase women’s participation in sport in Iraq this has declined following the war [15]. The reasons for this are multi-factorial and relate to radical political, cultural and religious changes, in addition to concerns about the safety of women [15].

Findings from this study highlight key distinctions between health care delivery in Kurdistan and that of the developed world. It is unsurprising that the timeframe from date of injury to ACL surgery was much longer (mean of 40 months), compared to 6–12 months reported in developed countries [1, 16]. This may have contributed to the high percentage of meniscal tears and chondral lesions among this cohort and likely reflects the inaccessibility and inadequacies of health care in Iraq, particularly the limited number of specialist surgeons [3, 8, 8]. Limited research capacity [8], accredited courses and qualified health care educators hinder the development of specialist skills across all health care professions [17]. Patients in this study were reviewed by the surgeon because of ‘word-of-mouth referrals’, which may explain the increasing number of cases performed each year, even during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, knee surgeons in Kurdistan should raise their profiles amongst local soccer teams to help capture all ACL injuries.

The lack of physiotherapists necessitated the adoption of a simple home-based programme. In a small prospective randomised study, Hohmann et al. (2011) found no additional benefit of ACL rehabilitation supervised by a physiotherapist compared to an unsupervised approach [18]. The low revision rates and improved Lysholm scores may indicate that the home-based programme was appropriate for the needs of patients in this study, but a larger randomised controlled trial would be needed to draw any conclusions about its efficacy in this setting. In their 2012 systematic review, Kruse et al. found six studies comparing home-based therapies alone versus physiotherapy led rehabilitation following ACLR [12]. Most studies included patient reported outcome measures such as Lysholm, Tegner and anterior cruciate ligament quality of life (ACL-QOL) scores as well as post-operative measurements of knee range of motion (ROM). The studies each found either no difference in functional outcomes or differences in favour of the home-based therapy group (such as a higher ACL-QOL scores in one study and better knee ROM in another). A more recent study by Lim et al. found that although patients treated with home-based therapy alone regained their knee strength, those who received physiotherapy led rehabilitation had better recovery of proprioception and functional knee movement [19].

The TAS scores indicate that patients in this study did not return to their pre-injury level of activity on average, yet the main reason for ACL failure was the resumption of sport or strenuous activity earlier than advised. Return to sport or high-level activity is based on a range of factors which include: physical examination findings, functional assessment, return to sport tests and psychological readiness [20]. In light of these considerations, our patients may have needed more support or closer supervision with this challenging aspect of ACL rehabilitation. Nevertheless, the lack of resources and health care professionals provides a strong case for further research to investigate the efficacy of home-based rehabilitation programmes following elective and trauma surgery in Iraq and other LMIC. Although the NHS represents a distinctly different health care structure, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed increasing strains on the workforce due to the introduction of the elective recovery plan [21]. Furthermore, supported self-management (democratising self-care) is part of the NHS Long-Term Plan which aims to give patients choice and control over how their care is delivered. The option of ACL home-based rehabilitation, for example, may enable patients to tailor what can be long and intensive treatment around their individual needs [22].

Our findings also prompt consideration of conservative management as a treatment option in place of surgical reconstruction of the ACL. A 2021 umbrella study of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found only two randomised controlled trials comparing conservative management with surgical treatment, both of which found no difference between the two interventions [23], unfortunately these were the only high-quality studies found on this subject, and heavily rely on physiotherapy led rehabilitation which is largely unavailable to the population studied in this report making this infeasible option.

Strengths

Due to the lack of robust health information systems and specialist knee surgeons [9], this is likely to be one of the only studies of ACL injuries in Kurdistan. Real-time data entry by the performing surgeon is a potential source of bias, but it may have also enhanced data accuracy.

Limitations

The limitations of this study should be considered in the context of the poor resource setting in which it was conducted, with no national surveillance on orthopaedic elective procedures. We do not have data about patient adherence, rate of progression through the criteria-based stages or patients’ experiences of managing the programme at home.

Unsurprisingly attrition in the outcome data increased with time post-surgery. In Iraq, patients may have to travel long distances from neighbouring cities or regions to access specialist surgeons, which impact follow-up attendance along with the lack of systems to track patients after discharge. Alternatively, patient’s may not have been motivated to attend follow-up because of their improvement in symptoms and function, as indicated by the Lysholm scores.

The requirement for revision was assessed throughout follow-up and was confirmed by telephone contact in June 2022, thus patients were at different stages of their post-operative recovery. However, the majority of patients were beyond one-year post-injury which can be considered as adequate time for graft integration and muscular function required for return to the majority of activities [24].

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the management and rehabilitation of ACL injuries in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, highlighting key health care challenges in this country. Patients who completed a home-based rehabilitation programme after ACLR had low revision rates and improved Lysholm scores over a 15-month period. Further research is required to investigate the efficacy and feasibility of home-based rehabilitation programmes following trauma and elective surgery in both LMIC and the developed world.

References

Sanders TL, MaraditKremers H, Bryan AJ, Larson DR, Dahm DL, Levy BA, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ (2016) Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears and reconstruction: A 21-year population-based study. Am J Sports Med 44:1502–1507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516629944

Anthony CR, Moore M, Hilborne LH, Rooney A, Hickey S, Ryu Y, Botwinick L (2010) Strengthening health care in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Moramarco S, Basa FB, Alsilefanee HH, Qadir SA, EmbertiGialloreti L (2020) Developing a public health monitoring system in a War-torn Region: a field report from Iraqi Kurdistan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 14:620–622. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2019.116

Joshipura M, Gosselin RA (2020) Surgical burden of musculoskeletal conditions in low- and middle-income countries. World J Surg 44:1026–1032

Mousa S (2020) Building social cohesion between Christians and Muslims through soccer in post-ISIS Iraq. Science 369:866–870. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.ABB3153

International monetary fund (2019) World economic outlook database October 2019–WEO groups and aggregates information. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/02/weodata/groups.htm#oem. Accessed 14 Jun 2020

Filbay SR, Grindem H (2019) Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 33:33–47

Hilfi TK AL, Lafta R, Burnham G (2013) Health services in Iraq. The Lancet 381:939–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7

World Confederation for Physical Therapy (WCPT) (2018) Survey reveals global state of the physical therapy profession | World Physiotherapy. https://world.physio/news/surveys-reveal-global-state-of-the-physical-therapy-profession. Accessed 22 May 2022

NGMV Charity. https://ngmvcharity.co.uk/. Accessed 19 Jun 2022

Wright RW, Preston E, Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Spindler KP, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Wolf BR, Williams GN, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Parker RC, Kaeding C, Marx RG, Mc Carty EC, Wolcott M (2008) ACL reconstruction rehabilitation: a systematic review part I. J Knee Surg 21:217. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0030-1247822

Kruse LM, Gray B, Wright RW (2012) Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg–Ser A 94:1737–1748

Cavanaugh JT, Powers M (2017) ACL rehabilitation progression: where are we now? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 10:289–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-017-9426-3

Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, Rodkey WG, Kocher MS, Steadman JR (2009) The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm score and Tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee: 25 years later. Am J Sports Med 37:890–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546508330143

Al-Wattar NSY, Hussein F, Hussein AA (2010) Women’s narratives of sport and war in Iraq. Muslim Women and Sport. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880630-28

Collins JE, Katz JN, Donnell-Fink LA, Martin SD, Losina E (2013) Cumulative incidence of ACL reconstruction after ACL injury in adults: role of age, sex, and race. Am J Sports Med 41:544–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546512472042

Jalal Al-Mosawi A (2020) Iraq healthcare system before covid-19 pandemic. Int J Res Studies Med Health Sci 5:2456–6373

Hohmann E, Tetsworth K, Bryant A (2011) Physiotherapy-guided versus home-based, unsupervised rehabilitation in isolated anterior cruciate injuries following surgical reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:1158–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1386-8

Lim JM, Cho JJ, Kim TY, Yoon BC (2019) Isokinetic knee strength and proprioception before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparison between home-based and supervised rehabilitation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 32:421–429. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-181237

Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, Fink C, Diermeier T, Rothrauff BB, Svantesson E, Hamrin-Senorski E, Hewett TE, Sherman SL, Lesniak BP, Bizzini M, Chen S, Cohen M, Villa-Della S, Engebretsen L, Feng H, Ferretti M, Fu FH, Imhoff AB, Kaeding CC, Karlsson J, Kuroda R, Lynch AD, Menetrey J, Musahl V, Navarro RA, Rabuck SJ, Siebold R, Snyder-Mackler L, Spalding T, van Eck C, Vyas D, Webster K, Wilk K (2020) Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Orthop J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967120930829

NHS England (2022) Delivery plan for tackling the Covid-19 backlog of elective care

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2020) Supported self-management summary guide

Blom AW, Donovan RL, Beswick AD, Whitehouse MR, Kunutsor SK (2021) Common elective orthopaedic procedures and their clinical effectiveness: umbrella review of level 1 evidence. The BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1511

Salmon L, Russell V, Musgrove T, Pinczewski L, Refshauge K (2005) Incidence and risk factors for graft rupture and contralateral rupture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 21:948–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARTHRO.2005.04.110

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by ZS and NK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by NK and SJ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose and have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kader, N., Jones, S., Serdar, Z. et al. Home-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the Kurdistan region of Iraq: epidemiology and outcomes. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 33, 481–488 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-022-03431-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-022-03431-8