Abstract

Background

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and fear of recurrence (FOR) are frequently experienced by cancer patients. This study aimed to improve cancer survivors’ CRF, FOR, quality of life (QOL), and heart rate variability (HRV) through Qigong and mindfulness interventions.

Methods

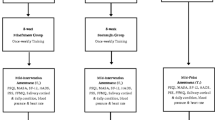

A quasi-experimental design was adopted, and 125 cancer survivors were recruited using snowball sampling. The participants were assigned to 1 of 3 groups (Qigong, mindfulness, and control) based on their needs and preferences. All groups received 4 h of nutrition education at the pretest (T0). CRF, FOR, and QOL questionnaires and HRV parameters were used as the measurement tools. Data were collected at the pretest (T0), posttest (T1), and follow-up (T2).

Results

Qigong had a better effect on improving CRF (ΔT1-T0 = − 0.108, ΔT2-T1 = − 0.008) and FOR (ΔT1-T0 = − 0.069, ΔT2-T1 = − 0.150) in the long term, while mindfulness improved QOL (ΔT1-T0 = 0.096, ΔT2-T1 = 0.013) better in the long term. Both Qigong and mindfulness had a short-term effect in improving SDNN (Q: ΔT1-T0 = 1.584; M: ΔT1-T0 = 6.979) and TP (Q: ΔT1-T0 = 41.601; M: ΔT1-T0 = 205.407), but the improvement in LF (Q: ΔT2-T1 = − 20.110; M: ΔT2-T1 = − 47.800) was better in the long term.

Conclusion

HRV evaluation showed that Qigong and the mindfulness interventions had short-term effects in significantly improving overall physical and mental health, self-emotional regulation, and QOL and relieving fatigue and autonomic dysfunction. HRV may serve as an observational indicator of interventions to improve physical and mental health. The consistent practice of mind-body interventions is the primary means of optimizing overall health and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cancer burden is a global concern. In 2020, there were 19.29 million new cancer cases and 9.96 million deaths, both of which included more males than females. By 2040, the cancer burden will increase by 50% [1], representing major challenges for global cancer care delivery. In particular, the current global COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented. However, delivering mind–body interventions for cancer survivors are necessary and must not be delayed.

Cancer survivors, unlike other patients, face more significant unknowns and physical and mental health risks. In general, they exhibit cancer-related symptoms such as fatigue, pain, anxiety, fear, depression, cognitive impairment, and sleep disorders, affecting their quality of life (QOL) [2,3,4]. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and fear of recurrence (FOR) are the most common symptoms [5,6,7,8]. Most cancer survivors consider major issues challenging to address through medical care services [9, 10]. In extreme cases, CRF can limit the ability of cancer survivors to reintegrate into normal life and return to work [6], and FOR can lead to despair, low morale, and even suicidal thoughts [7], creating a heavy burden. Clinical studies and experiences have shown that appropriate early mind–body interventions can improve cancer patients’ physical and mental symptoms, QOL, and overall survival rate [11]; enhance their self-management ability and confidence through lifestyle changes [12].

The psychological distress caused by CRF and FOR among cancer survivors is four times that of the general population [13]; distress is related to increased sympathetic nervous (SN) activity and decreased parasympathetic nervous (PSN) activity, resulting in autonomic dysfunction [3, 14], impacting cancer recovery [15]. Recent studies have shown that heart rate variability (HRV) parameters are closely related to cancer-related physical and mental health problems, autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, and homeostasis [3, 4, 6, 14, 16, 17]. HRV is also an important physiological indicator to objectively assess stress, mental health, and self-emotional regulation as well as improvements due to mind–body interventions [14, 16,17,18,19]. Low HRV can lead to an increase in CRF [3, 18]. Psychological stress can also lead to a decrease in HRV [17, 19]. Mood changes reflect a decrease in PSN activity (high-frequency power, HF) or an increase in SN activity (lower-frequency power, LF) [17]. In addition, high HRV represents an increase in adaptive capacity and higher self-regulation and efficiency [20].

An increasing number of studies have shown that helping cancer survivors establish a new lifestyle can promote overall physical and mental health after their cancer diagnosis and is an indispensable component of cancer care and interventions [2, 3, 10, 21]. Mind–body therapies in cancer care enhance the interaction between the mind and body, inducing physical and mental relaxation and improving overall physical health and well-being [22]. Among such therapies, Qigong and mindfulness decompression are increasingly regarded as adjuvant cancer therapies [2, 22, 23]. Qigong, which combines physical and mental exercise, involves slow and gentle limb movements, breathing regulation, meditation, relaxation, and self-massage techniques. Continuous practice can enhance physical health and vitality, alleviate fatigue and negative emotions, and improve sleep and QOL [2, 22,23,24,25,26,27]. Qigong significantly increases overall HRV [16] and the related parameters standard deviation of NN (SDNN) and HF and significantly decreases LF [28]. Mindfulness involves being self-aware of what is happening at the moment with an open mind; focusing on and accepting physical sensations, emotional feelings and thoughts without judgement; and allowing oneself to live in the present moment [10, 29]. Mindfulness can help cancer survivors improve their self-awareness, coping effectiveness, cognitive function, and communication skills in the face of future uncertainty, helping to alleviate fatigue, psychological stress, anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and FOR, enhance overall physical and mental health [2, 3, 22, 23, 29,30,31], improve overall HRV [32, 33], increase SDNN and HF and decrease LF [33]. These changes can activate physical perception, improve focus, promote vitality, enhance emotional regulation abilities, facilitate a gradual return to a calm and pleasant state, and improve self-management [28, 32].

However, malnutrition is very common in cancer survivors [11, 34, 35]; 89% of cancer survivors believe that nutrition is extremely important in cancer care, and 57% indicate that more nutrition interventions are needed [35]. Appropriate nutritional assessment and early intervention can reduce the physical and mental stress caused by cancer [2], improve cancer survivors’ overall physical and mental health and QOL and reduce the risk of cancer progression [34]. Thus, nutrition education is also an important part of cancer care delivery.

Mind–body interventions can help cancer survivors optimize their overall physical and mental health during treatment and the recovery stage and can be used as adjuvant therapies. Patients are free to choose interventions based on their preferences and different needs to increase their long-term participation in mind–body interventions [5, 12]. Cancer survivors can then establish a new lifestyle and obtain the maximum benefit from treatment.

Materials and methods

This study uses a quasi-experimental research design. Participants were recruited and screened by a nonprofit cancer foundation in Taiwan through snowball sampling. The inclusion criteria were (1) completion of conventional cancer treatment and recovery for at least 1 month or more; (2) no cancer recurrence; and (3) no history of moderate to severe arrhythmia. This study obtained approval certificates from two hospitals’ institutional review boards (IRBs), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design

In this study, the subjects were divided into a Qigong group (QG), a mindfulness group (MG), and a control group (CG) according to their personal needs and preferences. Three questionnaires (on CRF, FOR, and QOL) and HRV were used as measurement tools. The measurement time points were at pretest (T0), posttest (T1, at the end of the 12-week intervention course), and follow-up (T2, 3 months after the end of the intervention), and the study period was a total of 6 months. After completing the T0 measurement, all participants immediately received a 4-h cancer nutrition education session taught by a nutritionist, who instructed the participants on consuming balanced diets and nutritional supplementation and obtaining adequate nourishment (intaking variety, quantities, proportions, and frequency of food groups) to maintain physical health. In addition, Qigong and nutrition instructional DVDs and a mindfulness teaching manual were also distributed to encourage the three groups of participants to practice at home to familiarize themselves with the intervention techniques and integrate them into their daily lives.

Interventions

The Qigong and mindfulness sessions each lasted 2 h, occurring once per week for 12 weeks.

Qigong

There are many types of Qigong. In this study, we used an easy-to-learn form, Daoyin Yangsheng Gong Shi Er Fa (12-movement Qigong form) [36], and a national-level martial arts instructor was invited to train the participants. Progressive teaching was adopted, and the course objectives were as follows:

-

1.

Enhance cardiopulmonary function and promote qi and blood circulation through inhalation and exhalation and gentle extension of the limbs as the basis for core physical fitness

-

2.

Achieve self-healing and deep relaxation of the body through standing pole exercises and seated meditation

-

3.

Stimulate the blood circulation and relax the muscles and joints through leg massage

Mindfulness

The mindfulness courses were taught by a psychological counseling professor in a medical university. Participants were taught to examine their physical and emotional status after cancer treatment independently. The objectives of the course were as follows:

-

1.

Use mindfulness to alleviate various physical and mental symptoms during recovery from cancer

-

2.

Learn mindfulness and meditation, experience the mind and body living in the moment, avoid thoughts of suffering and cancer recurrence

-

3.

Develop internal positive energy, discover the ability to overcome adversity, restore health, and start a new life

Measurement instruments

CRF questionnaire

The 10-item CRF questionnaire was developed by Lee et al. (2018) [37], based on the diagnosis criterion of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) [38]. A 5-point Likert scale is used to assess the degree of fatigue experienced in the past 2 weeks; the higher the score is, the more severe the CRF symptoms. The Cronbach’s α for the internal consistency reliability of the total scale was 0.878, indicating that this scale is a reliable and effective CRF measurement tool [37].

FOR questionnaire

The 15-item FOR questionnaire was verified by Lee et al. (2018) [37], based on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI) developed by Simard and Savard (2009) [39]. A 5-point Likert scale is used to assess the degree of FOR in the past 1 month. Higher scores indicate more severe FOR symptoms. The Cronbach’s α for the internal consistency reliability of the total scale was 0.954, indicating that this scale is a reliable and effective tool for evaluating FOR [37].

QOL questionnaire

The 27-item 4th edition of the Chinese version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) was used to measure QOL. A 5-point Likert scale is used to assess QOL in the past 7 days. The scale has four dimensions. For the physical well-being and emotional well-being dimensions, the higher the score is, the worse the QOL, and for the social/family well-being and functional well-being dimensions, the higher the score is, the better the QOL. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the 4 dimensions ranged from 0.81 to 0.93. Cronbach’s α values between 0.74 and 0.85 indicated significant cross-validation (p < 0.001) [40].

HRV parameters

Electrocardiography (ECG) was performed using a CheckMyHeart Handel HRV device. ECG lead II was recorded for 5 min in a seated position to avoid too much variation in HRV parameters. The definition of each HRV parameter is provided below [16, 41]:

-

1.

SDNN: an indicator of overall ANS nerve activity, an increase indicates improvement

-

2.

HF: a PSN activity indicator, an increase suggests an improvement in the self-regulation of emotions

-

3.

LF: a SN activity indicator or an indicator of SN and PSN coregulation, a decrease indicated as a stress-reducing effect

-

4.

Total power (TP): an overall physical performance index, low values indicate fatigue, lack of vitality or powerlessness, and an increase indicates improvements

-

5.

LF/HF: an autonomic nerve balance indicator, the normal range of 0.5–2.5 indicates ANS balance and resilience to emotional disorders

Data analysis

All measurement data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software. The descriptive statistics are presented as the percentage distribution for the demographic characteristics of participants. Improvement interventions were determined by subtracting the mean and standard deviation of the posttest from those of the pretest. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post hoc test was performed to compare the degree of change in the dependent variables among the 3 groups.

Results

The 125 participants who met the inclusion criteria were assigned to the QG (n = 51), the MG (n = 38), or the CG (n = 36) based on their personal needs and preferences. Data were collected in three waves, and data collection was complete in August 2020.

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. 92.8% of the participants were female, and 7.2% were male. Participants varied in age from 34 to 75 years, with an average age of 54.4 (SD = 9.1) years. The largest proportion of participants (44.0%) was in the 50–59 age group. Breast cancer (72%) was the most common cancer type due to the study sampling distribution, and colorectal cancer (5.6%) was the second most common cancer type.

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of T1 minus T0 (T1 − T0) and T2 minus T1 (T2 − T1) to compare the differences among the three groups over three-time points. The comparison of differences at (T1 − T0) showed that the CRF score decreased in both the QG (− 0.108 ± 0.467) and MG (− 0.292 ± 0.519) but increased in the CG (0.019 ± 0.509). The FOR score decreased in the QG (− 0.069 ± 0.806) and MG (− 0.279 ± 0.572) but increased in the CG (0.181 ± 0.721). The QOL score increased in the QG (0.129 ± 0.534) and MG (0.096 ± 0.359) but decreased in the CG (− 0.045 ± 0.355). These outcomes indicated that both Qigong and mindfulness reduced the effects of CRF and FOR, and improved QOL. Regarding the HRV parameters, SDNN and TP both increased in the QG and MG and decreased in the CG, indicating that both Qigong and mindfulness optimized overall health status and reduced fatigue. HF increased in the MG but decreased in the QG and CG, indicating that mindfulness improved emotional self-regulation. LF decreased in the CG but increased in the QG and CG. LF/HF increased in the QG and MG but decreased in the CG. The comparison of differences at (T2-T1) showed that CRF exhibited a continuous downward trend in the QG but slightly increased in the MG and CG. FOR exhibited a continuous downward trend in the QG, first increased and then decreased in the CG, and increased in the MG. QOL increased in the MG, first increased and then decreased in the QG, and continuously decreased in the CG. These outcomes indicated that regular Qigong practice resulted in long-term improvement effects in CRF and FOR, but the long-term improvement effects of mindfulness were better for QOL. Regarding the HRV parameters, SDNN, LF, HF, and TP all decreased in QG and MG, only LF improved, indicating that Qigong and mindfulness had long-term stress-reducing effects. For the CG, SDNN, HF, and TP first increased and then decreased, indicating that maintaining nutrition was the foundation of recovery for overall physical and mental health wellbeing.

Because the initial values (T0) for the variables in the three groups were different, the direct use of the mean for the test would have caused serious inaccuracies. Therefore, Table 3 provides the ANOVA results for the difference between the posttest and pretest values for each variable was used to evaluate the differences among the 3 groups. Because the difference at (T1 − T0) for QOL did not satisfy the homogeneity of variance, Brown-Forsythe ANOVA was used. All other variables satisfied the homogeneity of variance, and when significant differences were obtained, Duncan or Tamhane’s T2 tests were used for post hoc analysis. Regarding the differences at (T1 − T0), CRF and FOR were relieved more significantly in the MG than in the CG. Regarding QOL, there was no significant difference among the 3 groups. For HRV parameters, except for HF, the average increases of the other parameter values in the QG and MG were significantly greater than those in the CG. Regarding the difference at (T2 − T1), there was no significant difference in CRF and QOL among the 3 groups; however, FOR in the MG was significantly greater than that in the CG and QG. For HRV parameters, the increase in TP in the CG was significantly greater than that in the MG, indicating that compared with that in the MG, the continuous improvement in TP was better in the CG. This finding indicates that if Qigong and mindfulness are not sustained, their beneficial effects on CRF, FOR, QOL and HRV may also not be sustained.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate HRV as an indicator of the beneficial effects of mind–body interventions on cancer survivors. Based on the T0 scores for the three groups, the perceived severities of CRF and FOR and poor QOL in the QG and MG were higher than those in the CG, which was also confirmed by the lower overall HRV values in the QG and MG than in the CG. This result is consistent with many studies showing that low HRV is associated with physical and mental health problems and poor QOL, leading to autonomic dysfunction [3, 16,17,18,19]. Most participants in this study were female (92.8%); only 7.2% were male. Although the number of new-onset cases and deaths is greater among males than among females [1], this gender imbalance is similar to that reported in most studies [12, 25]. Therefore, mind–body intervention care should be diverse, with a large amount of technical content to increase attractiveness [31], thereby encouraging male cancer patients to actively participate in self-management.

This study showed that regarding the short-term effect (T1), Qigong and mindfulness can reduce cancer survivors’ fatigue, psychological stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms and improve their overall QOL; these findings are consistent with the results of related studies [9, 42]. Qigong and mindfulness can activate ANS and maintain homeostasis, thus improving the overall health status, self-regulation of emotions and QOL and relieving fatigue; these findings indicate that changes in HRV can be used as physiological indicators to observe improvements in physical and mental health through mind–body intervention care, an observation that is consistent with that in the study by Larkey et al. [16]. In addition, HF increased only in the MG, indicating that the short-term effect of mindfulness on the self-regulation of emotions was better than that of Qigong; however, the LF index did not decrease as expected but instead increased. This may have occurred because during the 3-month home participation period, the lack of technical proficiency and the lack of guidance from teachers and peers generated psychological pressure and internal emotional changes that were reflected through HRV.

Regarding the medium-/long-term effect (T2), the actual beneficial effect of Qigong in the improvement of CRF and FOR can be maintained for a longer time than that of mindfulness. However, regarding the improvement in QOL, the duration of the improvement generated through mindfulness was longer than that of Qigong. Although the improvement in SDNN, HF, and TP was lower and only the effect on LF was optimal, Qigong and mindfulness reduced psychological stress, a finding consistent with the results of related studies [3, 28]. Therefore, continuous participation is the primary means to optimize the goals of mind–body interventions. The reason that the alleviation of CRF and FOR was not maintained in the MG may be that mindfulness is a skill that emphasizes mind–body interaction and interpersonal communication rely on a healthy mind. Mindfulness requires constant practice in daily life to become familiar with such skills, and unlike Qigong, it is difficult to imitate mindfulness instructions through videos, to increase proficiency and confidence in practice. Additionally, FOR, SDNN, HF, and TP first increased and then decreased in the CG, which indicated the importance of balanced nutrition in cancer care delivery.

Regarding the degree of change in each variable among the three groups, for the short-term effect at T1, CRF, FOR, SDNN, LF, TP, and LF/HF exhibited better improvement in the two experimental groups. For the medium-/long-term effects at T2, FOR was alleviated more effectively in the MG. This finding indicates that mindfulness can help cancer survivors improve self-awareness and concentration and provide coping strategies to face future uncertainties, FOR, poor cognition, and emotional and behavioral disorders [7, 10, 32, 43]. Schell et al. [43] showed that mindfulness can significantly alleviate fatigue, slightly alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms and improve QOL slightly at the end of the intervention but may result in little to no difference in QOL up to 6 months, with the alleviating effect on anxiety and depression maintained for up to 6 months. This finding is consistent with the results in this study. Additionally, TP was significantly higher in the QG than in the MG at T2, and the reason for this finding may be that the CG comprised participants who perceived themselves to be in good physical and mental health, as verified by the fact that their initial values for each variable were better than those of participants in the QG and MG. After the CG received dietary adjustments for 6 months, TP increased significantly. Therefore, interventions must be practiced consistently and implemented in daily life to achieve continuous improvement, and social support cannot be interrupted.

The physiological and psychological distress that is prevalent in cancer survivors continuously increases in severity with disease progression, the emergence of new health problems, and prolonged survival time [2, 9]. The comprehensive study results indicate that the health management of cancer survivors must be patient-centered through mind–body interventions and that their needs and preferences should be given priority to improve participation and persistence [5, 12]. Early, appropriate, and continuous mind–body interventions must encourage practice in daily life and then gradual cultivation of new habits that are essential for promoting a healthy lifestyle. Furthermore, the mutual support of society and a cancer peer group as well as adherence to exercise to enhance self-management are necessary to promote the continuous optimization of physical, psychological, self-regulatory functions and social adaptability. These are effective ways to relieve cancer-related physical and mental symptoms and improve QOL and the overall survival rate.

This study has some limitations. Instructional videos and manuals for the interventions were distributed to participants. They were encouraged to practice at home every week for at least 5 h. However, due to the lack of regular follow-up visits, it was impossible to immediately understand the difficulties they encountered in practice. Additionally, participants were not asked to report weekly training hours. Therefore, the improvement in long-term effects and health outcomes may have been affected, which is an insufficiency of this study.

Conclusions

Promoting mind–body interventions for cancer survivors during treatment and recovery can help them effectively relieve the physical and psychological symptoms of CRF and FOR and enhance their QOL. Long-term and continuous intervention management for cancer survivors through peer-assisted learning with cancer peers, healthcare teams, and cancer support groups could enhance adherence and persistence and facilitate evidenced-based anticancer lifestyle strategies and ensure more substantial health benefits. The application of HRV wearable devices in intervention management can effectively assist cancer survivors in monitoring their physical and mental health status.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Borgi M, Collacchi B, Ortona E, Cirulli F (2020) Stress and coping in women with breast cancer: unravelling the mechanisms to improve resilience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 119:406–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.10.011

Gosain R, Gage-Bouchard E, Ambrosone C, Repasky E, Gandhi S (2020) Stress reduction strategies in breast cancer: review of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic based strategies. Semin Immunopathol 42(6):719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-020-00815-y

Shih CH, Chou PC, Chou TL, Huang TW (2021) Measurement of cancer-related fatigue based on heart rate variability: observational study. J Med Internet Res 23(7):e25791. https://doi.org/10.2196/25791

Krueger E, Secinti E, Mosher CE, Stutz PV, Cohee AA, Johns SA (2021) Symptom treatment preferences of cancer survivors: does fatigue level make a difference? Cancer Nurs 44(6):E540–E546. https://doi.org/10.3389/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000941

Ruiz-Casado A, Álvarez-Bustos A, de Pedro CG, Méndez-Otero M, Romero-Elías M (2021) Cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a review. Clin Breast Cancer 21(1):10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/10.1016/j.clbc.2020.07.011

Hall DL, Luberto CM, Philpotts LL, Song R, Park ER, Yeh GY (2018) Mind-body interventions for fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncol 27(11):2546–2558. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4757

Nilsson R, Næss-Andresen TF, Myklebust TÅ, Bernklev T, Kersten H, Haug ES (2021) Fear of recurrence in prostate cancer patients: a cross-sectional study after radical prostatectomy or active surveillance. Eur Urol Open Sci 25:44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2021.01.002

Thong MS, van Noorden CJ, Steindorf K, Arndt V (2020) Cancer-related fatigue: causes and current treatment options. Curr Treat Options Oncol 21(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-020-0707-5

Luberto CM, Hall DL, Chad-Friedman E, Park ER (2019) Theoretical rationale and case illustration of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for fear of cancer recurrence. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 26(4):449–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09610-w

Popescu RA, Roila F, Arends J, Metro G, Lustberg M (2021) Supportive care: low cost, high value. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 41:240–250. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_320041

Hathiramani S, Pettengell R, Moir H, Younis A (2021) Relaxation versus exercise for improved quality of life in lymphoma survivors—a randomised controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv 15(3):470–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00941-4

Yang M, Zhang Z, Nice EC, Wang C, Zhang W, Huang C (2022) Psychological intervention to treat distress: an emerging frontier in cancer prevention and therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1877(1):188665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188665

Lavín-Pérez AM, Collado-Mateo D, Mayo X, Liguori G, Humphreys L, Jiménez A (2021) Can exercise reduce the autonomic dysfunction of patients with cancer and its survivors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 12:712823. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712823

Palma S, Keilani M, Hasenoehrl T, Crevenna R (2020) Impact of supportive therapy modalities on heart rate variability in cancer patients–a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 42(1):36–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1514664

Larkey L, Kim W, James D, Kishida M, Vizcaino M, Huberty J, Krishnamurthi N (2020) Mind-body and psychosocial interventions may similarly affect heart rate variability patterns in cancer recovery: implications for a mechanism of symptom improvement. Integr Cancer Ther 19:1534735420949677. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735420949677

Kim HG, Cheon EJ, Bai DS, Lee YH, Koo BH (2018) Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig 15(3):235–245. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2017.08.17

Álvarez-Bustos A, de Pedro CG, Romero-Elías M, Ramos J, Osorio P, Cantos B, Maximiano C, Méndez M, Fiuza-Luces C, Méndez-Otero M et al (2021) Prevalence and correlates of cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 29(11):6523–6534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06218-5

Tibensky M, Mravec B (2021) Role of the parasympathetic nervous system in cancer initiation and progression. Clin Transl Oncol 23(4):669–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/10.1007/s12094-020-02465-w

Martins AD, Brito JP, Oliveira R, Costa T, Ramalho F, Santos-Rocha R, Pimenta N (2021) Relationship between heart rate variability and functional fitness in breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Healthc (Basel) 9(9):1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091205

Osypiuk K, Kilgore K, Ligibel J, Vergara-Diaz G, Bonato P, Wayne PM (2020) “Making peace with our bodies”: a qualitative analysis of breast cancer survivors’ experiences with Qigong mind–body exercise. J Altern Complement Med 26(9):827–834. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0406

Karim S, Benn R, Carlson LE, Fouladbakhsh J, Greenlee H, Harris R, Henry NL, Jolly S, Mayhew S, Spratke L et al (2021) Integrative oncology education: an emerging competency for oncology providers. Curr Oncol 28(1):853–862. https://doi.org/10.3389/10.3390/curroncol28010084

Ford CG, Vowles KE, Smith BW, Kinney AY (2020) Mindfulness and meditative movement interventions for men living with cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 54(5):360–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/10.1093/abm/kaz053

Klein P (2017) Qigong in cancer care: theory, evidence-base, and practice. Med 4(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines4010002

Wayne PM, Lee MS, Novakowski J, Osypiuk K, Ligibel J, Carlson LE, Song R (2018) Tai Chi and Qigong for cancer-related symptoms and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 12(2):256–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0665-5

Sowada KM (2019) Qigong: benefits for survivors coping with cancer-related fatigue. Clin J Oncol Nurs 23(5):465–469. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.465-469

Yin J, Tang L, Dishman RK (2020) The efficacy of Qigong practice for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ment Health Phys Act 19:100347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100347

Goldbeck F, Xie YL, Hautzinger M, Fallgatter AJ, Sudeck G, Ehlis AC (2021) Relaxation or regulation: The acute effect of mind-body exercise on heart rate variability and subjective state in experienced Qi Gong practitioners. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 8:6673190. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6673190

Johns SA, Tarver WL, Secinti E, Mosher CE, Stutz PV, Carnahan JL, Talib TL, Shanahan ML, Faidley MT, Kidwell KM et al (2021) Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on fatigue in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 160:103290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103290

Zhang D, Lee EK, Mak EC, Ho CY, Wong SY (2021) Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull 138(1):41–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldab005

Mikolasek M, Witt CM, Barth J (2021) Effects and implementation of a mindfulness and relaxation App for patients with cancer: mixed methods feasibility study. JMIR Cancer 7(1):e16785. https://doi.org/10.2196/16785

Crosswell AD, Moreno PI, Raposa EB, Motivala SJ, Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Bower JE (2017) Effects of mindfulness training on emotional and physiologic recovery from induced negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology 86:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.003

Park H, Oh S, Noh Y, Kim JY, Kim JH (2018) Heart rate variability as a marker of distress and recovery: the effect of brief supportive expressive group therapy with mindfulness in cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther 17(3):825–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735418756192

Byun M, Kim E, Kim J (2021) Physical and mental health factors associated with poor nutrition in elderly cancer survivors: insights from a nationwide survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(17):9313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179313

Sullivan ES, Rice N, Kingston E, Kelly A, Reynolds JV, Feighan J, Power DG, Ryan AM (2021) A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin Nutr ESPEN 41:331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.10.023

Chinese Health Qigong Association (2014) Daoyin Yangsheng Gong Shi Er Fa. Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, China

Lee YH, Lai GM, Lee DC, Tsai Lai LJ, Chang YP (2018) Promoting physical and psychological rehabilitation activities and evaluating potential links among cancer-related fatigue, fear of recurrence, quality of life, and physiological indicators in cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther 17(4):1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735418805149

Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G (2001) Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 19(14):3385–3391. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385

Simard S, Savard J (2009) Fear of cancer recurrence inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 17(3):241–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y

Cheung YB, Goh C, Wee J, Khoo KS, Thumboo J (2009) Measurement properties of the Chinese language version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general in a Singaporean population. Ann Acad Med Singap 38(3):225–229

Rubik B (2017) Effects of a passive online software application on heart rate variability and autonomic nervous system balance. J Altern Complement Med 23(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2016.0198

Zeng Y, Xie X, Cheng AS (2019) Qigong or Tai Chi in cancer care: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Oncol Rep 21(6):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0786-2

Schell LK, Monsef I, Wöckel A, Skoetz N (2019) Mindfulness‐based stress reduction for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3(3):CD011518. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011518.pub2

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the cancer patients who participated in the studies.

Funding

This research was funded by Formosa Cancer Foundation, grant number AI-107019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. Lee and Y.P. Chang; methodology, Y.H. Lee and Y.P. Chang; software, D.C. Lee; validation, D.C. Lee; formal analysis, D.C. Lee; investigation, Y.P. Chang and Y.H. Lee; resources, J.T. Lee, E.Y. Huang, Y.P. Chang, and L.J. Tsai Lai; data curation, Y.H. Lee; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. Lee; writing—review and editing, Y.P. Chang; supervision, Y.P. Chang; project administration, Y.P. Chang; funding acquisition, Y.P. Chang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation (protocol code 108WFDB310036 and August 1st, 2019 of approval), and Fooyin University Hospital (protocol code FYH-IRB-108–10-01 and January 7th, 2020 of approval).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, YH., Chang, YP., Lee, JT. et al. Heart rate variability as an indicator of the beneficial effects of Qigong and mindfulness training on the mind–body well-being of cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 31, 59 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07476-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07476-7