Abstract

Purpose

Adequate integration of palliative care in oncological care can improve the quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Whether such integration affects the use of diagnostic procedures and medical interventions has not been studied extensively. We investigated the effect of the implementation of a standardized palliative care pathway in a hospital on the use of diagnostic procedures, anticancer treatment, and other medical interventions in patients with incurable cancer at the end of their life.

Methods

In a pre- and post-intervention study, data were collected concerning adult patients with cancer who died between February 2014 and February 2015 (pre-PCP period) or between November 2015 and November 2016 (post-PCP period). We collected information on diagnostic procedures, anticancer treatments, and other medical interventions during the last 3 months of life.

Results

We included 424 patients in the pre-PCP period and 426 in the post-PCP period. No differences in percentage of laboratory tests (85% vs 85%, p = 0.795) and radiological procedures (85% vs 82%, p = 0.246) were found between both groups. The percentage of patients who received anticancer treatment or other medical interventions was lower in the post-PCP period (40% vs 22%, p < 0.001; and 42% vs 29%, p < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Implementation of a PCP resulted in fewer medical interventions, including anticancer treatments, in the last 3 months of life. Implementation of the PCP may have created awareness among physicians of patients’ impending death, thereby supporting caregivers and patients to make appropriate decisions about medical treatment at the end of life.

Trial registration number

Netherlands Trial Register; clinical trial number: NL 4400 (NTR4597); date registrated: 2014–04-27.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diagnostic and therapeutical medical interventions can be used for seriously ill patients to prolong life and manage symptoms [1,2,3]. At the end of life, patients are frequently admitted to the hospital and often undergo multiple and costly medical interventions [4,5,6,7]. One can debate whether these interventions are always beneficial for patients with a limited life expectancy [6, 8]. In general, it is believed that aggressive care, e.g. the use of chemotherapy or admission to an intensive care unit, should be avoided at the end of life when possible [4,5,6,7,8]. Early integration of palliative care in oncological care has been suggested to improve quality of life in patients with advanced cancer [3, 9,10,11,12]. However, the effect of early integration of palliative care on the utilization of diagnostic procedures and medical interventions at the end of life has not been studied extensively.

In a cross-sectional study, end-of-life discussions about goals of care between healthcare professionals and patients have been found to be associated with less aggressive medical interventions at the end of life [7]. However, evaluation of the Serious Illness Care Program in patients with advanced cancer did not show a reduction in aggressive care or healthcare use at the end of life [8, 13, 14]. Many oncology healthcare professionals are not specialized in palliative care; however, they are responsible for the general coordination of palliative care in oncology patients. In the Netherlands, this role is formalized in the Dutch national quality framework of palliative care [15]. To support them to integrate palliative care more into their daily oncology practice, we developed a standardized palliative care pathway (PCP).

The PCP is a structured electronic medical checklist which supports healthcare professionals in integrating oncological and palliative care. We recently performed a pre-post intervention study on the effects of implementing this PCP in oncology departments in a large teaching hospital. Implementation of the PCP did not have a significant overall impact on place of death, hospitalizations at the end of life, and several aspects of advance care planning (ACP) [16]. However, in the group of patients for whom the PCP was actually used, more patients died outside the hospital compared to patients in the pre-PCP group [16]. These findings suggest that the PCP may have had an effect on decisions about clinical care.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether the PCP had an impact on medical care applied in patients with advanced cancer. We studied whether implementation of the PCP (1) affected the use of diagnostic procedures, anticancer treatment, and other medical interventions in patients’ last 3 months of life and (2) resulted in more involvement of a pain management team, a specialized palliative care team, and specialized psychosocial caregivers in patients’ last 3 months of life.

Methods

Design and study population

This study is part of a study performed in a large teaching hospital investigating the effects of implementing a standardized palliative care pathway (PCP) for patients with advanced cancer. In a pre- and post-intervention study, data were collected of adult patients with cancer who had been treated at the in- and outpatients clinics of the Departments of Oncology/Haematology and Lung Diseases and died between February 2014 and February 2015 (pre-PCP period) or between November 2015 and November 2016 (post-PCP period). Patients referred to other hospitals for further treatment were excluded.

During the 12-month pre-PCP period, care was provided as usual. At the end of this period, the PCP was implemented in departments involved. All nurses and physicians of the participating departments were trained on how to use the PCP in a 30–45-min training session; other hospital staff was informed in writing. We aimed to use the PCP for at least 50% of patients with cancer at the end of their life. To facilitate familiarity with the PCP, the post-PCP period started 9 months after implementation. The study design has been described elsewhere [16].

Palliative care pathway

The PCP is a structured medical checklist based on Dutch and international guidelines for palliative care and ACP [17,18,19]. The pathway addresses all four domains of palliative care: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. It is integrated in the patient’s electronic medical record, in which a special button guides the physician to the PCP. After opening, various prompts can be used, among these a prompt that offers guidance for healthcare professionals for ACP conversations and supports documentation of these conversations. Another prompt facilitates the coordination of care, e.g. for asking consultation of the pain management team, specialized palliative care team, and specialized psychosocial caregivers; the communication with the general practitioner; and involvement of family and relatives. The PCP can be used next to tumor-specific care pathways.

Indications to start the PCP were a negative answer to the surprise question [20] (‘would I be surprised if this patient would die within a year?’); deterioration of patient’s performance status; severe complication of a medical treatment; patient’s wish to stop all medical treatments; and/or no more anticancer treatment options available.

Data collection

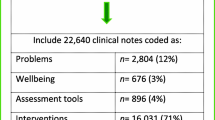

Data were collected retrospectively after patients’ death. Information was collected from their electronic medical records and included patients’ diagnosis, sociodemographic characteristics, and the use of diagnostic and medical interventions in their last 3 months of life (90 days). These included diagnostic procedures (laboratory tests such as blood sampling and urinalysis and radiology procedures); anticancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, anti-hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, and surgery); other medical interventions (e.g. paracentesis, stenting, blood transfusions, and pleurodesis); and consultation of a pain management team, specialized palliative care team, and/or specialized psychosocial caregivers (spiritual counsellor, psychologist, social worker).

To promote consistency of data collection, 1 out of 20 electronic medical records were double checked by 2 different data collectors independently. Discrepancies were discussed and documented in a logbook. In case of a discrepancy, the particular outcome was adapted following the discussion and all medical records were checked for the parameter for which the discrepancy was found.

Statistical analyses

Patients were included in either the pre- or post-PCP period; in the post-PCP period, patients were included irrespective of whether the PCP had been used. Furthermore, a per-protocol analysis was carried out, utilizing data from patients for whom the PCP was actually used during the post-PCP period. The statistical significance of differences in use of diagnostic procedures, medical interventions, and supportive care consultations between the pre- and post-PCP period was tested using t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests, where applicable. As the study concerned a secondary analysis of a larger study, a power analysis was not performed.

Results

Patients

We included 424 patients in the pre-PCP period and 426 patients in the post-PCP period; their mean age at death was 70.9 and 71.5 years, respectively. Both groups consisted of more males than females (58% and 56% were male). The most common primary cancer types were lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and haematological cancers (Table 1).

Diagnostic procedures

In the last 90 days of life, most patients underwent multiple diagnostic procedures. Laboratory tests were performed in 85% of the patients in both periods with a median of 9.5 and 8 tests per patient in the pre- and post-PCP period, respectively. Further, 85% and 82% of the patients underwent radiology procedures, with a median number of 5 and 4 procedures per patient, respectively. Comparable results were found in the per-protocol analyses where (Table 2).

Medical interventions

During the last 90 days of life, 40% of patients who died during the pre-PCP period received anticancer treatment, compared to 22% of the patients dying in the post-PCP period (p < 0.001). Additionally, significantly more patients in the pre-PCP period received systemic anticancer treatment in comparison to the patients in the post-PCP period (30% and 17%, respectively, p < 0.001), with chemotherapy as the main treatment used. In the pre-PCP group, more patients underwent local treatment, particularly radiotherapy (10% and 4%, respectively, p < 0.001). Comparable results were found in the per-protocol analyses (Table 3).

In the pre-PCP period, significantly more patients received medical interventions (other than anticancer treatment) (42%) compared with the post-PCP period (29%, p < 0.001). The two most frequently used medical interventions included paracentesis (16% and 13%, respectively) and blood transfusion (17% and 11%, respectively). In the pre-PCP period, patients more often underwent two or more interventions compared to the post-PCP period (26% and 14% respectively, p = 0.034). This difference was even more pronounced in the per-protocol analysis (26% and 7% respectively, p = 0.002) (Table 4).

Consultation of palliative care specialists and specialized psychosocial care

In the last 90 days of life, a pain management team was consulted in the pre- and post-period for 6% and 3% of the patients, respectively (p = 0.246), and a specialized palliative care team was consulted for 14% and 17%, respectively (p = 0.198). A spiritual counsellor was consulted for 23% of patients in the pre-PCP period compared to 19% in the post-PCP period (p = 0.141). In the group of patients for whom the PCP was started (N = 236), the palliative care team was consulted more often compared to the patient group in the pre-PCP period (14% vs 23%, respectively, p = 0.003) (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that significantly fewer patients received medical interventions in the last 3 months of life after implementation of a standardized PCP to support early integration of palliative care in general oncology care. The reduction was especially evident for the use of systemic and local anticancer therapies.

The percentage of patients receiving any kind of anticancer treatment in the last 3 months of life decreased from 40% during the pre-PCP period to 22% during the post-PCP period, which was mainly caused by fewer patients receiving chemotherapy (24% and 14%, respectively). Comparison of results with the results from other studies is difficult, as studies differ widely regarding the time frames studied, varying between 14 and 180 days before patients’ death [6, 21,22,23,24]. In a retrospective cohort study in cancer patients, the utilization of chemotherapy at least once in the last 180 to 30 days of life was analysed in seven developed countries, including the USA and the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, chemotherapy was used among 18.1% and 10.6% of patients, respectively, compared to 38.7% and 10.6% in the USA [25]. Nevertheless, the percentage of patients receiving chemotherapy in the post-PCP period in our study seems relatively low (14% in the last 90 days of life), compared to other studies, where 3 to 22.2% of patients were found to receive chemotherapy in the last 14 to 30 days before death [6, 21,22,23,24].

Our finding that fewer patients in the post-PCP period received local radiotherapy is noteworthy too. Radiotherapy with palliative intent may alleviate symptoms related to advanced cancer. Several studies have investigated radiotherapy use at the end of life and found rates between 6.4 and 28% in the last 30 days of life [26,27,28], which suggests that radiotherapy was relatively infrequently used in our study, both before and after implementation of the PCP (in 10 and 4%, respectively, in the last 3 months of life).

The utilization of other medical interventions, such as paracentesis (for ascites and thoracocentesis) and blood transfusion, was also lower in the post-PCP period (from overall 42 to 29%). In a retrospective cohort study, 10.1% of the patients with advanced cancer underwent paracentesis and 39.5% of the patients received blood transfusions in their last 30 days of life [27]. In our post-PCP group, only 13% of the patients underwent paracentesis and 11% of the patients received a blood transfusion in the last 90 days of their life.

In our study, patients underwent many diagnostic procedures in the last 3 months of life. Implementing the PCP was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the median number of laboratory tests per patient. No differences were found for the percentage of patients for whom laboratory tests or radiological procedures were performed. Comparing these results with other studies is difficult, because previous studies mainly evaluated the use of diagnostic procedures in the dying phase, i.e. the last days and hours of life [29,30,31]. Involvement of a pain management team, a specialized palliative care team, and specialized psychosocial caregivers did not increase after implementing the PCP. However, in the group in which the PCP was actually started, significantly more patients received care of a specialized palliative care team.

A previous paper on this study described that the implementation of the PCP did not result in a better documentation of ACP conversations, fewer hospitalizations at the end of life, or more out-of-hospital deaths [16]. The reduction of medical and, to some extent, diagnostic interventions that we found in the current study may nevertheless have been the result of increased awareness among healthcare staff of patients being in their last months of life. Such awareness may have been created by the extensive education of the healthcare professionals on using the PCP. Awareness of patients’ limited life expectancy has been found to result in fewer undesirable diagnostic procedures and medical interventions by others too [29,30,31]. End-of-life discussions and shifting to symptom-centred care goals have been associated with less utilization of anticancer treatment, including radiotherapy, in the last year of life [7, 32, 33]. The fact that we found comparable results in the intention-to-treat and the per-protocol analysis also suggests that implementation of the PCP created a general level of awareness about the importance of recognizing patients’ limited life expectancy.

Consultation of palliative care specialists and specialized psychosocial care may have contributed to the reduction of medical interventions. However, in the Netherlands, non-specialized healthcare professionals are responsible for the general coordination of palliative care, including the detection of specific palliative care needs for which palliative care specialists are consulted [15]. Given the rather large reduction in the use of anticancer treatment (from 40 to 22%), and the relatively small rise in consultations of palliative care specialists (from 14 to 17%), an increased awareness of healthcare staff seems more important [15].

This study is one of the few intervention studies in which healthcare professionals not specialized in palliative care were supported in giving structured palliative care and initiating ACP conversations. Previous similar studies mainly focused on the last weeks of life, whereas we measured the utilization of medical interventions in the last 3 months of life [13, 29]. There are several limitations to our study. Chemotherapy use in the last 14 days of life is suggested to be an indicator of ‘aggressive care’ [8, 13, 14, 21]. However, it is complex to distinguished appropriate versus inappropriate care at the end of life: interventions that can be considered ‘aggressive care’ for some patients can be used to manage and alleviate symptoms and suffering in others [1,2,3]. Prognostication of patients with advanced cancer is difficult on an individual basis and it is complex to predict which patients would benefit from a medical intervention [34]. Moreover, this study only collected data about medical interventions as provided in the hospital; information on interventions outside the hospital is lacking.

Conclusion

In a prospective pre- and post-implementation study on a digital palliative care pathway (PCP) to support the integration of palliative care in oncology care, we found that implementation of the PCP resulted in fewer medical interventions, including anticancer treatments, in the hospital in the last 3 months of life.

Implementation of the PCP whether it was started or not may have created awareness among healthcare professionals of patients’ impending death and palliative care needs, and could support discussions about patients’ preferences and appropriate medical decision-making in the last phase of life. It is not possible to draw conclusions about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of decisions of medical interventions in our study. In future research, the appropriateness of medical intervention for patients with an advanced illness deserves more attention.

Data availability

The data of this study are kept by A. P. and are available upon request.

References

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine (2015) Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US)

Roeland EJ, LeBlanc TW (2016) Palliative chemotherapy: oxymoron or misunderstanding? BMC Palliat Care 21(15):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0109-4

Kaasa S, Lode JH, Aapro M et al (2018) Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 19(11):e588-653

Massa I, Balzi W, Altini M et al (2018) The challenge of sustainability in healthcare systems: frequency and cost of diagnostic procedures in end-of-life cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 26(7):2201–2208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4067-7

Carter HE, Winch S, Barnett AG et al (2017) Incidence, duration and cost of futile treatment in end-of-life hospital admissions to three Australian public-sector tertiary hospitals: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 7:e017661

Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J, Ho TH, Liu N, Barbera L, Saskin R, Porter J, Seung SJ, Mittmann N (2015) Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer 121(18):3307–3315. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29485

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A et al (2008) Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300(14):1665–1673

Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ (2008) Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol 26(23):3860–3866. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. Erratum In: J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jul 1;28(19):3205. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2011 Nov 20;29(33):4472

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721–1730

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z et al (2015) Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33(13):1438–1445

Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A et al (2017) Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35(8):834–841

Paladino J, Koritsanszky L, Neal BJ, Lakin JR, Kavanagh J, Lipsitz S, Fromme EK, Sanders J, Benjamin E, Block S, Bernacki R (2020) Effect of the Serious Illness Care Program on health care utilization at the end of life for patients with cancer. J Palliat Med 23(10):1365–1369. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0437

Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B et al (2003) Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol 21:1133–1138

IKNL/Palliactief (2017) Netherlands quality framework for palliative care. Available: https://www.palliaweb.nl/getmedia/f553d851-c680-4782-aac2-2520632f2e8d/netherlands-quality-framework-for-palliative-care_2.pdf. Accessed Oct 2017

van der Padt-Pruijsten A, Leys MBL, Oomen-de Hoop E, van der Heide A, van der Rijt CCD (2021) Effects of implementation of a standardized palliative care pathway for patients with advanced cancer in a hospital: a prospective pre- and postintervention study. J Pain Symptom Manage 62(3):451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.003

Schrijvers D, Cherny NI, ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2014) ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines on palliative care: advanced care planning. Ann Oncol 25 Suppl 3:iii138–42

National Care Standard for Palliative Care in the Netherlands 1.0 (2013) Coordination platform for Healthcare Standards and the Quality Institute. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Available from: https://www.netwerkpalliatievezorg.nl/Portals/141/zorgmodule-palliatieve-zorg.pdf. Accessed Dec 2013

(2011) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence End of life care for adults. London: NICE. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/QS13. [Accessed November 2013]

Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Adhikari NKJ (2017) The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Med J 189(13):E484–E493

Boddaert MS, Pereira C, Adema J et al (2020) Inappropriate end-of-life cancer care in a generalist and specialist palliative care model: a nationwide retrospective population-based observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 12(e1):e137–e145. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002302

Colombet I, Bouleuc C, Piolot A, Vilfaillot A, Jaulmes H, Voisin-Saltiel S, Goldwasser F, Vinant P, EFIQUAVIE study group (2019) Multicentre analysis of intensity of care at the end-of-life in patients with advanced cancer, combining health administrative data with hospital records: variations in practice call for routine quality evaluation. BMC Palliat Care 18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0419-4

Rochigneux P, Raoul JL, Beaussant Y, Aubry R, Goldwasser F, Tournigand C, Morin L (2017) Use of chemotherapy near the end of life: what factors matter? Ann Oncol 28(4):809–817. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw654

Matter-Walstra KW, Achermann R, Rapold R, Klingbiel D, Bordoni A, Dehler S, Jundt G, Konzelmann I, Clough-Gorr K, Szucs T, Pestalozzi BC, Schwenkglenks M (2015) Cancer-related therapies at the end of life in hospitalized cancer patients from four Swiss cantons: SAKK 89/09. Oncology 88(1):18–27. https://doi.org/10.1159/000367629

Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR et al (2016) Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA 315:272–283

Jones JA, Lutz ST, Chow E et al (2014) Palliative radiotherapy at the end of life: a critical review. CA Cancer J Clin 64:296–310

Wu SY, Singer L, Boreta L, Garcia MA, Fogh SE, Braunstein SE (2019) Palliative radiotherapy near the end of life. BMC Palliat Care 18(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0415-8

Dasch B, Kalies H, Feddersen B, Ruderer C, Hiddemann W, Bausewein C (2017) Care of cancer patients at the end of life in a German university hospital: a retrospective observational study from 2014. PLoS ONE 12(4):e0175124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175124

Veerbeek L, Van Zuylen L, Swart SJ, Jongeneel G, Van Der Maas PJ, Van Der Heide A (2008) Does recognition of the dying phase have an effect on the use of medical interventions? J Palliat Care 24(2):94–99

Campos-Calderon C, Montoya-Juarez R, Hueso-Montoro C, Hernandez-Lopez E, Ojeda-Virto F, Garcia-Caro MP (2016) Interventions and decision-making at the end of life: the effect of establishing the terminal illness situation. BMC Palliat Care 15(1):91

Geijteman ECT, Van der Graaf M, Witkamp FE, et al. (2018) Interventions in the last days of hospitalized patients with cancer: importance of awareness of impending death. BMJ Support Palliat Care 8(3):278–281

Hirvonen OM, Leskelä R-L, Grönholm L et al (2019) Assessing the utilization of the decision to implement a palliative goal for the treatment of cancer patients during the last year of life at Helsinki University Hospital: a historic cohort study. Acta Oncol 58(12):1699–1705

Ahluwalia SC, Tisnado DM, Walling AM et al (2015) Association of early patient-physician care planning discussions and end-of-life care intensity in advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 18:834–841

Engel M, van der Ark A, van Zuylen L, van der Heide A (2020) Physicians’ perspectives on estimating and communicating prognosis in palliative care: a cross-sectional survey. BJGP Open. 4(4):bjgpopen20X101078. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101078.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank C. van Leijen, K. Mataw, F. Smit, S. Meurs, and H. Nederveen for data collection and entry; F. Baar and C. van Leijen for developing and implementation of the PCP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Annemieke van der Padt-Pruijsten is the principal investigator and conceived the study with Maria B. L. Leys, Agnes van der Heide, and Carin C. D. van der Rijt. Data were analysed by Annemieke van der Padt-Pruijsten and Esther Oomen-de Hoopand; they interpreted the results together with Maria B. L. Leys, Agnes van der Heide, and Carin C. D. van der Rijt. Annemieke van der Padt-Pruijsten drafted the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to Dutch legislation, written informed consent of the patients was not required because data were gathered after the patient’s death by healthcare professionals of the hospital and processed anonymously. The Medical Ethical Research Committee of the Maasstad Hospital (TWOR 2013/51) approved the study at 19/12/2013. Netherlands Trial Register; clinical trial number: NL4400 (NTR4597); date registrated: 2014–04-27.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

C. C. D. van der Rijt received consulting fees from Kyowa Kirin. All remaining authors have declared they have no financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Padt-Pruijsten, A., Leys, M.B.L., Hoop, E.Od. et al. The effect of a palliative care pathway on medical interventions at the end of life: a pre-post-implementation study. Support Care Cancer 30, 9299–9306 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07352-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07352-4