Abstract

Purpose

Nausea is a common and distressful symptom among patients in palliative care, but little is known about possible socio-demographic and clinical patient characteristics associated with nausea at the start of palliative care and change after initiation of palliative care. The aim of this study was to investigate whether patient characteristics were associated with nausea at the start of palliative care and with change in nausea during the first weeks of palliative care, respectively.

Methods

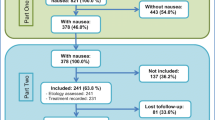

Data was obtained from the nationwide Danish Palliative Care Database. The study included adult cancer patients who were admitted to palliative care and died between June 2016 and December 2020 and reported nausea level at the start of palliative care and possibly 1–4 weeks later. The associations between patient characteristics and nausea at the start of palliative care and change in nausea during palliative care, respectively, were studied using multiple regression analyses.

Results

Nausea level was reported at the start of palliative care by 23,751 patients of whom 8037 also reported 1–4 weeks later. Higher nausea levels were found for women, patients with stomach or ovarian cancer, and inpatients at the start of palliative care. In multivariate analyses, cancer site was the variable most strongly associated with nausea change; the smallest nausea reductions were seen for myelomatosis and no reduction was seen for stomach cancer.

Conclusion

This study identified subgroups with the highest initial nausea level and those with the least nausea reduction after 1–4 weeks of palliative care. These latter findings should be considered in the initial treatment plan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data utilized in this study are available through the Danish Palliative Care Database. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data.

References

WHO (2016) WHO definition of palliative care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 01.07.2016

EAPC (2013) Atlas of palliative care in Europe 2013

Sundhedsstyrelsen (2017) Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats 5 2017

Collis E, Mather H (2015) Nausea and vomiting in palliative care. BMJ 351:h6249. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6249

Harder SL, Groenvold M, Herrstedt J et al (2019) Nausea in advanced cancer: relationships between intensity, burden, and the need for help. Support Care Cancer 27:265–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4326-7

Harder S, Herrstedt J, Isaksen J et al (2019) The nature of nausea: prevalence, etiology, and treatment in patients with advanced cancer not receiving antineoplastic treatment. Support Care Cancer 27:3071–3080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4623-1

LundhHagelin C, Seiger A, Furst CJ (2006) Quality of life in terminal care–with special reference to age, gender and marital status. Support Care Cancer 14:320–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0886-4

Brunelli C, Costantini M, Di Giulio P et al (1998) Quality-of-life evaluation: when do terminal cancer patients and health-care providers agree? J Pain Symp Manag 15:151–158

Teunissen SC, de Haes HC, Voest EE et al (2006) Does age matter in palliative care? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 60:152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.002

Vainio A, Auvinen A (1996) Prevalence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: An international collaborative study. Symptom Prevalence Group. J Pain Symptom Manage 12:3–10

Ventafridda V, De Conno F, Ripamonti C et al (1990) Quality-of-life assessment during a palliative care programme. Ann Oncol 1:415–420

Walsh D, Donnelly S, Rybicki L (2000) The symptoms of advanced cancer: relationship to age, gender, and performance status in 1,000 patients. Support Care Cancer 8:175–179

Hansen MB, Ross L, Petersen MA, et al (2019) Age, cancer site and gender associations with symptoms and problems in specialised palliative care: a large, nationwide, register-based study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001880

Iwase S, Kawaguchi T, Tokoro A, et al (2015) Assessment of cancer-related fatigue, pain, and quality of life in cancer patients at palliative care team referral: a multicenter observational study (JORTC PAL-09). PloS One 10:e0134022.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134022

Stromgren AS, Sjogren P, Goldschmidt D et al (2005) A longitudinal study of palliative care: patient-evaluated outcome and impact of attrition. Cancer 103:1747–1755. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20958

Labori KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Wester T et al (2006) Symptom profiles and palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer 14:1126–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0067-0

Modonesi C, Scarpi E, Maltoni M et al (2005) Impact of palliative care unit admission on symptom control evaluated by the edmonton symptom assessment system. J Pain Symptom Manage 30:367–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.007

Riechelmann RP, Krzyzanowska MK, O’Carroll A et al (2007) Symptom and medication profiles among cancer patients attending a palliative care clinic. Support Care Cancer 15:1407–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0253-8

Kirkova J, Rybicki L, Walsh D et al (2011) The relationship between symptom prevalence and severity and cancer primary site in 796 patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 28:350–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110391464

Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH et al (2001) Quality of life in advanced cancer patients: the impact of sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Brit J Cancer 85:1478–1485. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.2001.2116

Lee YJ, Suh SY, Choi YS et al (2014) EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL quality of life score as a prognostic indicator of survival in patients with far advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 22:1941–1948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2173-8

Teunissen SC, de Graeff A, de Haes HC et al (2006) Prognostic significance of symptoms of hospitalised advanced cancer patients. European J Cancer 42:2510–2516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.025

Ellershaw JE, Peat SJ, Boys LC (1995) Assessing the effectiveness of a hospital palliative care team. Palliat Med 9:145–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/026921639500900205

Kyriaki M, Eleni T, Efi P et al (2001) The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample. Int J Cancer 94:135–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.1439

Bedard G, Zeng L, Zhang L et al (2016) Minimal important differences in the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL to determine meaningful change in palliative advanced cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 12:e38-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12069

Badgwell BD, Aloia TA, Garrett J et al (2013) Indicators of symptom improvement and survival in inpatients with advanced cancer undergoing palliative surgical consultation. J Surg Oncol 107:367–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23236

Yennurajalingam S, Atkinson B, Masterson J et al (2012) The impact of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Palliat Med 15:20–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0219

Zimmermann C, Burman D, Follwell M et al (2010) Predictors of symptom severity and response in patients with metastatic cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 27:175–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109346307

Hansen MB, Adsersen M, Groenvold M (2021) Dansk Palliativ Database, Årsrapport 2020

Groenvold M, Adsersen M, Hansen MB (2016) Danish palliative care database. Clin Epidemiol 8:637–643. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.s99468

Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK et al (2006) The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 42:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022

Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al (2001) EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussel: EORTC Quality of Life Group

Lund Rasmussen C, Johnsen AT, Petersen MA et al (2016) Change in health-related quality of life over 1 month in cancer patients with high initial levels of symptoms and problems. Qual Life Res 25(2669):2674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1287-5

Giesinger JM, Loth FLC, Aaronson NK, et al (2020) Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol 118: 1–8

Pilz MJ, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI et al (2021) Evaluating the thresholds for clinical importance of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL in patients receiving palliative treatment. J Palliat Med 24:397–404. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0159

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G et al (2012) Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire core 30. Eur J Cancer 48:1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.059

Musoro JZ, Bottomley A, Coens C et al (2018) Interpreting European Organisation for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of life Questionnaire core 30 scores as minimally importantly different for patients with malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 104:169–181

Donnelly S, Walsh D (1995) The symptoms of advanced cancer. Semin Oncol 22:67–72

Hesketh PJ, Aapro M, Street JC et al (2010) Evaluation of risk factors predictive of nausea and vomiting with current standard-of-care antiemetic treatment: analysis of two phase III trials of aprepitant in patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 18:1171–1177

Osoba D, Zee B, Pater J et al (1997) Determinants of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer. Quality of Life and Symptom Control Committees of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 15:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.1.116

Warr D (2014) Prognostic factors for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol 722:192–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.015

Schmetzer O, Florcken A (2012) Sex differences in the drug therapy for oncologic diseases. Handbook of experimental pharmacology 411–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-30726-3_19

Society AC (2018) Nausea and vomiting. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/nausea-and-vomiting/what-is-it.html. Accessed 04.07.2018

Sundhedsstyrelsen (2012) Kvalme og opkastning i palliativ medicin, https://www.sst.dk/da/rationel-farmakoterapi/maanedsbladet/2012/maanedsblad_nr_4_april_2012/kvalme_og_opkastning_i_palliativ_medicin. Accessed 04.07.2018

Livstone E (2018) Overview of pancreatic endocrine tumors, https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/tumors-of-the-gi-tract/overview-of-pancreatic-endocrine-tumors. Accessed 04.07.2018

Stromgren AS, Goldschmidt D, Groenvold M, et al (2002) Self-assessment in cancer patients referred to palliative care: a study of feasibility and symptom epidemiology. Cancer 94: 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10222.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Danish Palliative Care Database for access to the data used in the article and all the specialized palliative care services in Denmark who delivered the data to the Danish Palliative Care Database.

Funding

The Danish Cancer society (grant number R56-A3126-12-S2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analyses were performed by Maiken Bang Hansen and Morten Aagaard Petersen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Maiken Bang Hansen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was based only on registers from the Danish Palliative Care Database; therefore, it had not impact on any individuals’ care and not required Ethics Committee approval according to Danish law. The study was conducted following the approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.nr.: 2007–58-0015/local j.nr. BFH-2014–033 I-Suite no. 02953).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, M.B., Adsersen, M., Rojas-Concha, L. et al. Nausea at the start of specialized palliative care and change in nausea after the first weeks of palliative care were associated with cancer site, gender, and type of palliative care service—a nationwide study. Support Care Cancer 30, 9471–9482 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07310-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07310-0