Abstract

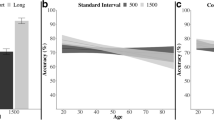

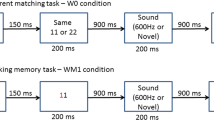

This study tested the modality effect on time judgment in a bisection task in children and adults when auditory and visual stimuli were presented in the same session. Cognitive capacities of children and adults were assessed with different neuropsychological tests. The results showed a modality effect, with the auditory stimuli judged longer than the visual stimuli. However, this modality distortion in time judgment was higher in the younger children. Statistical analyses revealed that the size of this time distortion was directly related to individual working memory capacities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Asaoka, R., & Gyoba, J. (2015). Effects of sensory modality and retention delay on time reproduction performance. The Japanese Journal of Psychonomic Science, 34(1), 53–59.

Atkinson, J. (2000). The developing visual brain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, 417–422.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 8, pp. 47–90). New York: Academic Press.

Bjorklund, D. V., & Causey, K. B. (2018). Children’s thinking: Cognitive development and individual differences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Bueti, D. (2011). The sensory representation of time. Frontiers in integrative neurosciences, 5(34), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2011.00034.

Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: What have learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110.

Chen, K.-M., & Yeh, S.-L. (2009). Asymmetric cross-modal effects in time perception. Acta Psychologica, 130, 225–234.

Church, R. M. (1984). Properties of the internal clock. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 423, 566–582.

Cohen, M. J. (1997). Examiner manual: Children memory scale. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace.

Cowan, N., Wood, N. L., Wood, P. K., Keller, T. A., Nugent, L. D., & Keller, C. V. (1998). Two separate verbal processing speeds contributing to verbal short-term memory span. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 127, 141–160.

Creelman, C. D. (1963). Human discrimination of auditory duration. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America, 34, 582–593.

Droit-Volet, S. (2013). Time perception in children: A neurodevelopmental approach. Neuropsychologia, 51, 220–234.

Droit-Volet, S. (2016). Development of time. Current Opinion in Behavioural Sciences, 8, 102–109.

Droit-Volet, S. (2017). Time dilation in children and adults: the idea of a slower internal clock in young children tested with different click frequencies. Behavioural Processes, 138, 152–159.

Droit-Volet, S., & Coull, J. (2016). Distinct developmental trajectories for explicit and implicit timing. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 150, 141–154.

Droit-Volet, S., Meck, W., & Penney, T. (2007). Sensory modality effect and time perception in children and adults. Behavioural Processes, 74, 244–250.

Droit-Volet, S., Tourret, S., & Wearden, J. (2004). Perception of the duration of auditory and visual stimuli in children and adults. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57A, 5, 797–818.

Droit-Volet, S., & Zélanti, P. (2013). Time sensitivity in children and adults: duration ratios in bisection. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66(4), 687–704.

Droit-Volet, S., & Zélanti, P. S. (2013). Development of time sensitivity and information processing speed. PLoS One, 8(8), e71424.

Gathercole, S. E., Pickering, S. J., Ambridge, B., & Wearing, H. (2004). The Structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Developmental Psychology, 40, 2, 177–190.

Gibbon, J. (1977). Scalar expectancy theory and Weber’s law in animal timing. Psychological Review, 84, 279–325.

Gibbon, J., Church, R. M., & Meck, W. H. (1984). Scalar timing in memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 423, 52–77.

Goldstone, S., & Goldfarb, J. (1964a). Auditory and visual time judgement. The Journal of General Psychology, 70, 369–387.

Goldstone, S., & Goldfarb, J. (1964b). Direct comparison of auditory and visual durations. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 483–485.

Goldstone, S., & Lhamon, W. T. (1972). Auditory-visual differences in human temporal judgement. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 34, 623–633.

Goldstone, S., & Lhamon, W. T. (1974). Studies of auditory-visual differences in human timing judgment, 1: Sounds are judged longer than lights. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 39, 63–82.

Grondin, S., Meilleur-Wells, G., Ouellette, C., & Macar, F. (1998). Sensory effects on judgements of short-time intervals. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 61, 261–268.

Gu, B.-M., van Rijn, H., & Meck, W. H. (2015). Oscillatory multiplexing of neural population codes for interval timing and working memory. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 48, 160–185.

Hallez, Q., & Droit-Volet, S. (2017). High levels of time contraction in young children in dual task are related to their limited attention capacities. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 161, 148–160

Hart, H., Radua, J., Mataix-Cols, D., & Rubia, K. (2012). Meta-analysis of fMRI studies of timing in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(10), 2248–2256.

Jain, A., Bansal, R., Kumar, A., & Singh, K. D. (2015). comparative study of visual and auditory reaction times on the basis of gender and physical activity levels of medical first year students. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research, 5(2), 124–127.

Johnstone, B., Erdal, K., & Stadler, M. A. (1995). The relationship between the wechsler memory scale-revised (WMS-R) attention index and putative measures of attention. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 2(2), 195–204.

Litovsky, R. (2015). Development of the auditory system. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 129, 55–72.

Lustig, C., & Meck, W. H. (2011). Modality difference in timing and temporal memory throughout the lifespan. Brain and Cognition, 77, 298–303.

Manly, T., Robertson, I. H., Anderson, V., & Nimmo-Smith, I. (1999). Tests of everyday attention for children. Flempton: Thames Valley Test Company.

McCormack, T. (2015). The development of temporal cognition. In: R. M. Lerner, L. S. Liben & U. Müller, Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, Cognitive Processes, 7th edition, Volume 2. Willey, pp. 624–670.

Ogden, R. S., Salominaite, E., Jones, L. A., Fisk, J. E., & Montgomery, C. (2011). The role of executive functions in human prospective interval timing. Acta Psychologica, 137, 352–358.

Ogden, R. S., Samuels, M., Simmons, F., Wearden, J., & Montgomery, C. (2017). The differential recruitment of short-term memory and executive functions during time, number, and length perception: An individual differences approach. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1–14.

Ogden, R. S., Wearden, J. H., & Montgomery, C. (2014). The differential contribution of executive functions to temporal generalization, reproduction and verbal estimation. Acta Psychologica, 152, 84–94.

Ortega, L., Lopez, F., & Church, R. M. (2009). Modality and intermittency effects on time estimation. Behavioural Processes, 81, 270–273.

Penney, T. B. (2003). Modality differences in interval timing: Attention, clock speed, and memory. In W. H. Meck (Ed.), Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing (pp. 209–234). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Penney, T. B., Gibbon, J., & Meck, W. H. (2000). Differential effects of auditory and visual signals on clock speed and temporal memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26, 1770–1787.

Penney, T. B., & Tourret, S. (2005). Les effets de la modalité sensorielle sur la perception du temps. Psychologie Française, 5(1), 131–143.

Rammsayer, T. H., Borter, N., & Troche, S. J. (2015). Visual-auditory differences in duration discrimination of intervals in the subsecond and second range. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 1626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01626.

Recanzone, G. H. (2009). Interactions of auditory and visual stimuli in space and time. Hear Res, 258(1–2), 89–99.

Rousseau, L., & Rousseau, R. (1996). Stop-reaction time and the internal clock. Perception and Psychophysics, 58, 434–448.

Roux, F., & Uhlaas, P. J. (2014). Working memory and neural oscillations: α-γ versus θ-γ codes for distinct WM information? Trends in cognitive sciences, 18(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.10.010.

Rustic, J., & Enns, J. T. (2015). Attentional development. In R. M. Lerner, L. Liben & U. Mueller (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 158–203). New York: Wiley.

Sowell, E. R., Delis, D., Stiles, J., & Jernigan, T. L. (2001). Improved memory functioning and frontal lobe maturation between childhood and adolescence: A structural MRI study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 7, 312–322.

Sowell, E. R., Peterson, B. S., Thompson, P. M., Welcome, S. E., Henkenius, A. L., & Toga, A. W. (2003). Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nature Neuroscience, 6(3), 309–315.

Stauffer, C. C., Haldemann, J., Troche, S. J., & Rammsayer, T. H. (2012). Auditory and visual temporal sensitivity: evidence for a hierarchical structure of modality-specific and modality-independent levels of temporal information processing. Psychological Research, 76, 20–31.

Treisman, M. (1963). Temporal discrimination and the indifference interval: Implications for a model of the” internal clock”. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 77(13), 1.

Truett, A., Hume, A. L., Wood, C., & Goff, W. R. L. (1984). Developmental and aging changes in somatosensory, auditory and visual evoked potentials. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology, 58, 14–24.

Tsujimoto, S. (2008). The prefrontal cortex: Functional neural development during early childhood. The Neuroscientist, 14(4), 345–358.

Walker, J., & Scott, K. (1981). Auditory-visual conflicts in the perceived duration of lights, tones, and gaps. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 1327–1339.

Wearden, J. (2016). The psychology of time perception. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wearden, J., Edwards, H., Fakhri, M., & Percival, A. (1998). Why sounds are judged longer than lights: Application of a model of the internal clock in humans. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 51B, 97–120.

Wearden, J., Todd, N., & Jones, L. (2006). When do auditory-visual difference in duration judgment occur. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 1709–1724.

Wechsler, D. (1998). WAIS III and WMS-III manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Zélanti, P., & Droit-Volet, S. (2011). Cognitive abilities explaining age-related changes in time perception of short and long durations. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 109(2), 143–157.

Zélanti, P., & Droit-Volet, S. (2012). Auditory and visual differences in time perception? An investigation from a developmental perspective with neuropsychological tests. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112, 296–311.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sophie Biron (Psychology Master’s student co-directed by a PhD student, Pierre Zélanti) who collected a large proportion (73%) of the children’s data at school, the other children being recruited by Quentin Hallez (PhD student). We also thank Laétitia Bartomeuf (research assistant) who collected the adults’ data at the university. We are also grateful to the directors and the teachers of the Elsa Triolet nursery school at Vic-Le-Conte and the “Centre” primary school at Issoire.

Funding

This study was funded by H2020 European Research Council (BE) (TIMESTORM—H2020—FETPROACT-2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Sylvie Droit-Volet declares that she has no conflict of interest. Quentin Hallez declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This experiment was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration. All children were voluntary to participate in this study. The children’s parents, and the students signed written informed consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the ethical standards of the French research committee (academy) of the French National Education Ministry.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Droit-Volet, S., Hallez, Q. Differences in modal distortion in time perception due to working memory capacity: a response with a developmental study in children and adults. Psychological Research 83, 1496–1505 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1016-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1016-5